Welcome back to The World of The Blood Road!

I hope you’ve enjoyed this blog series so far. If you missed Part II on travel and transportation in the Roman Empire, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In Part III, we’re going to take a brief look at one of the more unique acts of Emperor Caracalla: The Constitutio Antoninia.

As we shall see, this act had pros and cons, and it’s effects on the Roman world were far-reaching.

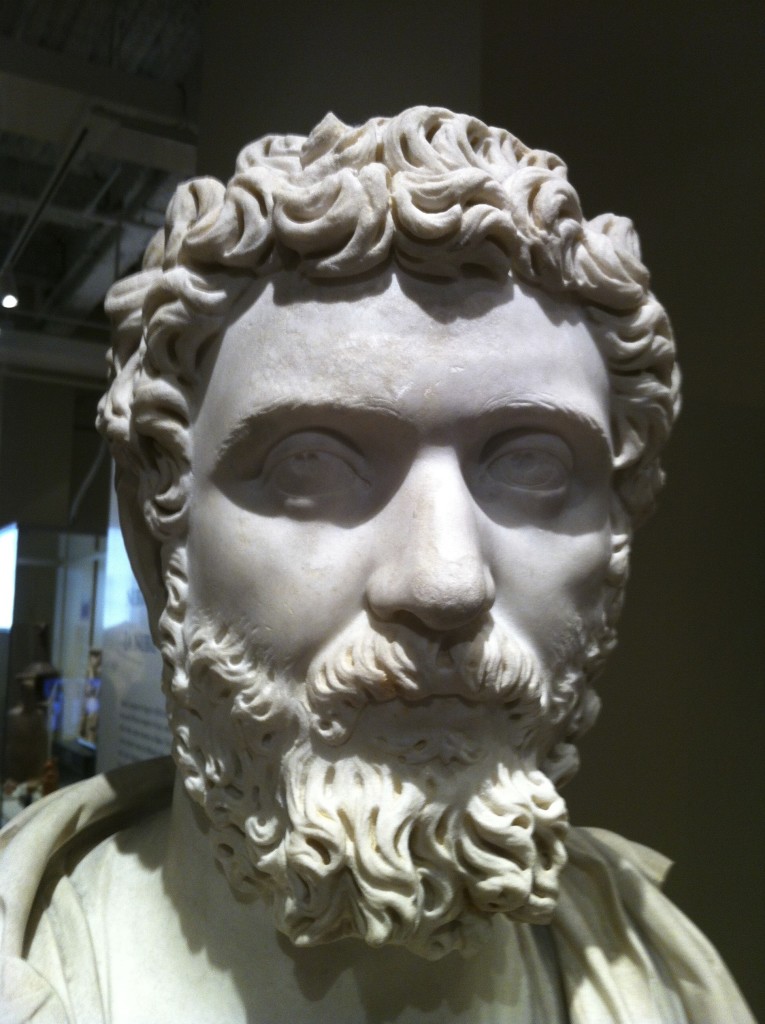

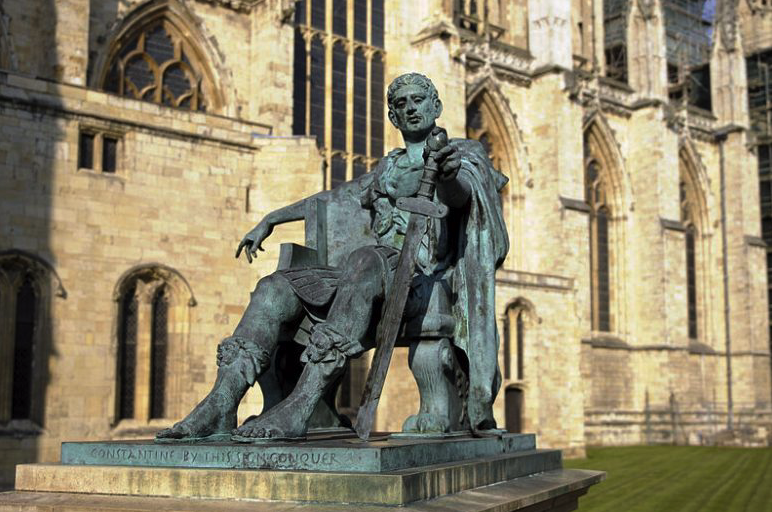

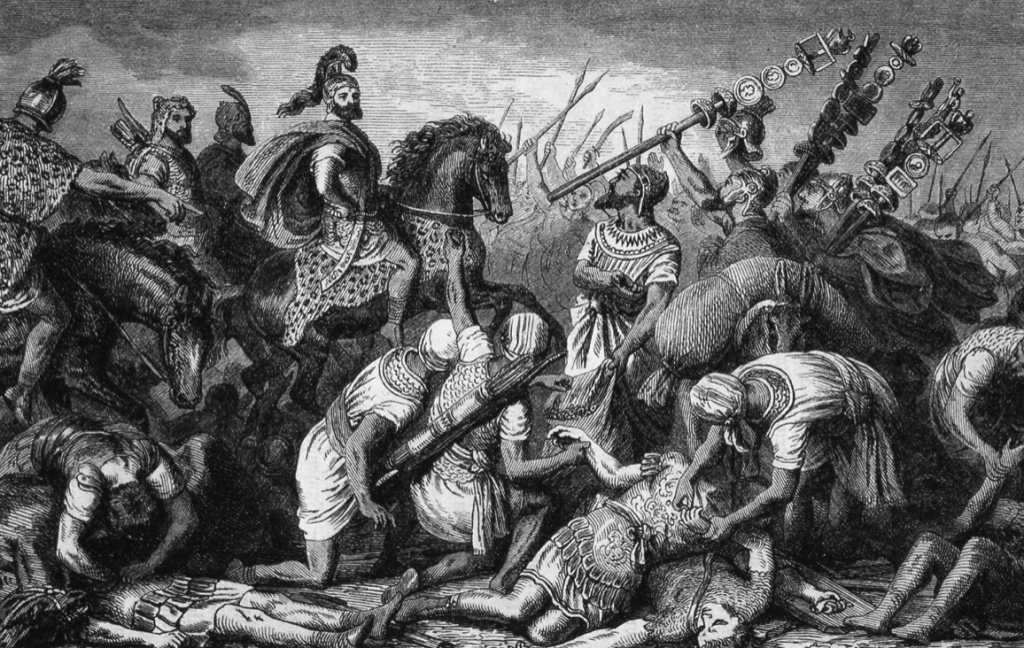

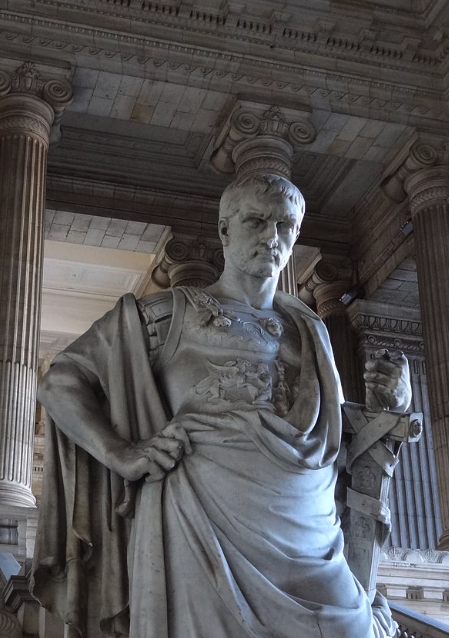

When we think about Emperor Caracalla, it’s hard to think of anything but blood and violence. After all, he may have begun his reign with a massacre in York, and then committed fratricide and ordered mass executions when he returned to Rome from Britannia.

The beginning of his reign was also punctuated by another act that has caused some debate among scholars over the years.

In A.D. 212, shortly after murdering his brother, Caracalla created an edict named the Constitutio Antoniniana which was, according to eminent historian, Michael Grant, “one of the outstanding features of the period, although whether it seemed the same to contemporaries is uncertain.”

So, what was the Constitutio Antoniniana? Why was it created? And what were the effects of this curious piece of legislation?

Let’s take each of these questions in turn.

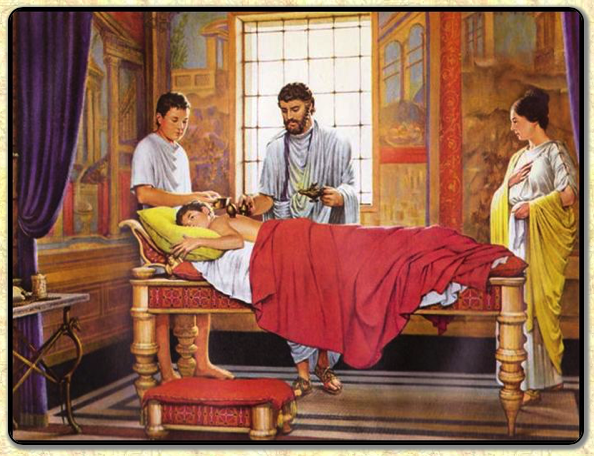

Giessen Papyrus 40 of the Constitutio Antoniniana

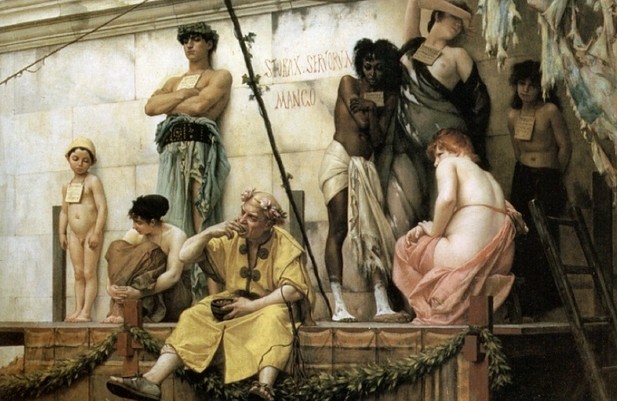

Basically, the Constitutio Antoniniana was an edict that granted citizenship to all freeborn men and women within the Roman Empire.

Think about that for a moment…

Whereas before, Roman citizenship had been primarily held by few, namely those who were from Italy itself, it was now held by every free man and woman across the whole of the Roman world. The only ones who appear to have been excluded were a group known as the dediticii, thought to be tribesman beyond the Danube and Euphrates frontiers who had recently been conquered by Rome.

This act had far-reaching impacts which we will look at shortly, but why was it created, and why at that particular moment in time?

There are a few possibilities.

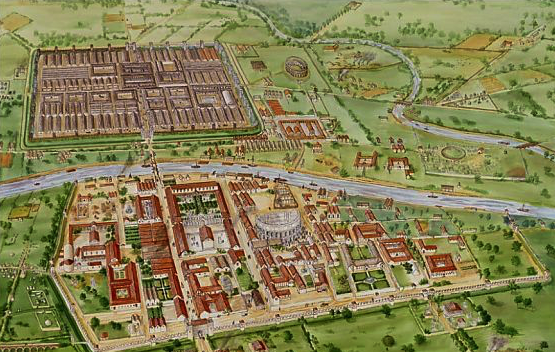

Map of the Roman Empire at its greatest extent (Oxford Research Encyclopedias)

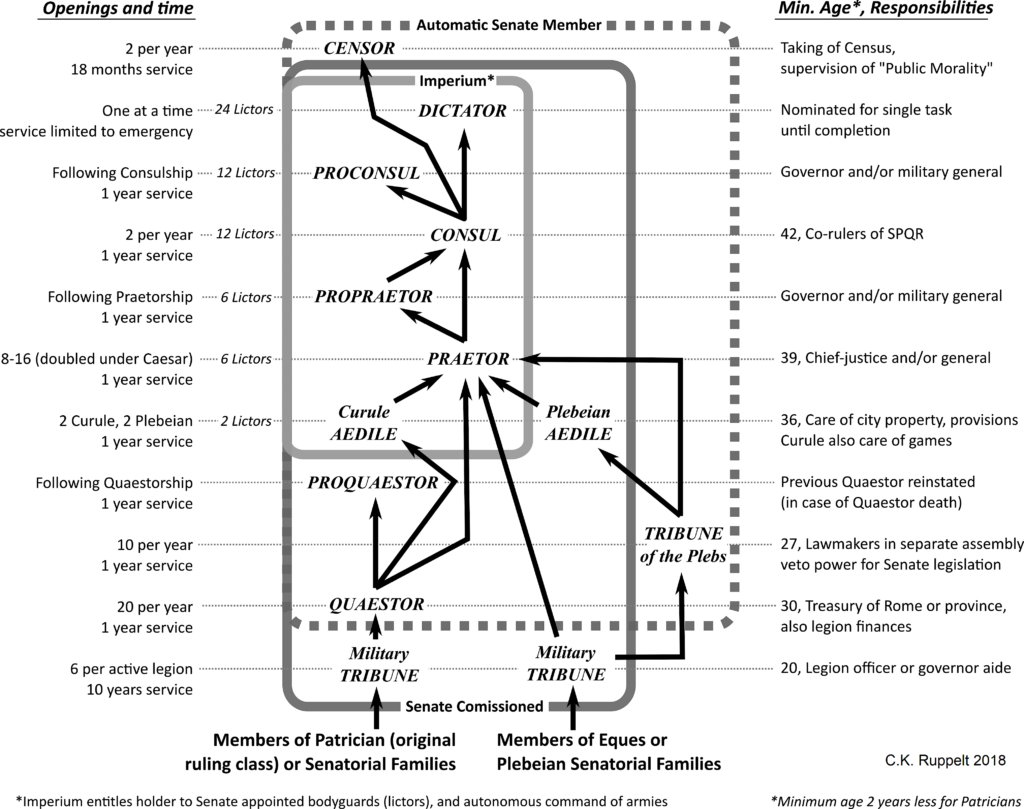

During the reign of Septimius Severus, Caracalla’s father, it is important to remember there there was a general shift happening, a more egalitarian movement in policy-making that sought to embrace all inhabitants of the Empire. Severus had previously, made drastic changes within the army itself by allowing legionaries to marry and by making it possible for men of equestrian status to move higher in the ranks into positions normally reserved for the senatorial class. This was the case for Lucius Metellus Anguis in the Eagles and Dragons series.

It is possible that Caracalla’s Constitutio Antoniniana was a next step in what was already his father’s policy-making direction. Let’s remember that Severus himself had been from Leptis Magna in Africa Proconsularis.

It is also important to remember that after the fall of the Praetorian prefect, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus, Septimius Severus appointed the legal jurists, Papinianus and Ulpianus as joint Praetorian prefects, clearly with a view to using their skills in drafting legislation. Of course, Papinianus perished during Caracalla’s proscriptions at the outset of his reign, but Ulpianus almost certainly had a hand in drafting the Constitutio Antoniniana.

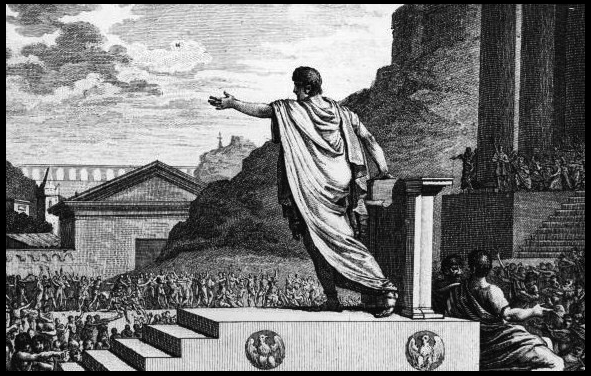

It was a major step in the creation of the first, Roman Communis Patria, a commonwealth in which provincials and Italians were now on equal footing. This would have appealed to Caracalla as well, for he was obsessed with Alexander the Great who had sought to create a grand, pan-Hellenic world. Caracalla sought to emulate Alexander, and this may have been an extension of that obsession.

Apart from being in line with Severus’ policies, however, it is quite possible that one of the main reasons Caracalla issued this edict at that time was to distract the world from the murder of his brother, Geta.

As discussed in Part I of this series, fratricide was frowned upon, even though Rome’s founding was based on such an act (poor Remus!).

The She-Wolf suckling the brothers, Romulus and Remus

But we would be doing ourselves a disservice if we explained the creation of this important legislation by saying it was merely a distraction from murder. It had other uses.

As we know, after his brother’s murder, Caracalla needed to secure his position, and so he emptied the imperial coffers in order to bribe the Praetorian Guard and give more money to the legions. His father had always taught him that ensuring the loyalty of the military was of utmost importance, and this is exactly what Caracalla did. But it left him with few funds.

So, by granting citizenship to all freeborn men and women across the Empire, he instantly increased the tax revenues many times over. Citizens had to pay manumission and inheritance taxes to the state, and his tax collectors no doubt set about their work.

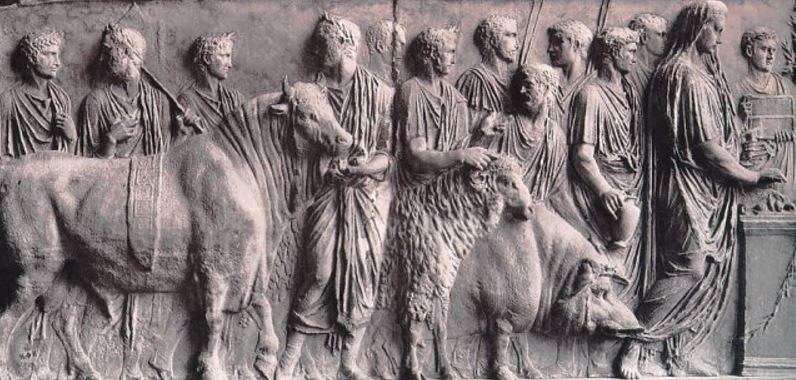

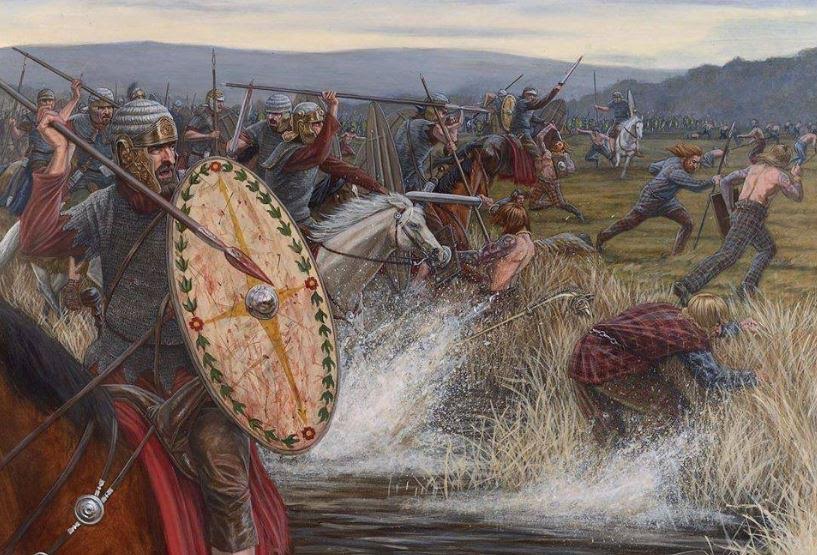

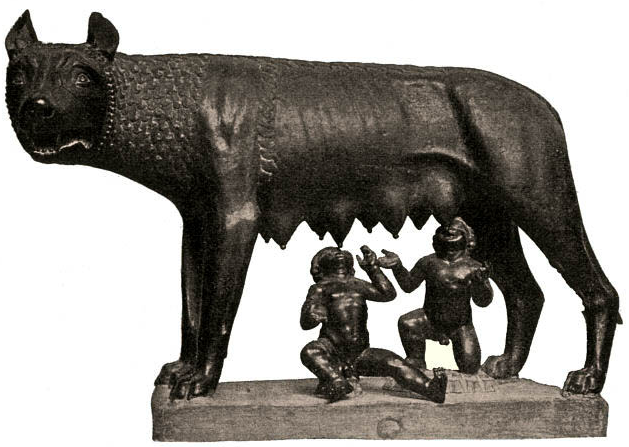

Roman Re-enactors on the March

Another important aspect of the Constitutio Antoniniana is that by greatly increasing the citizenry, many more men could enlist in Rome’s legions. To be a legionary, one had to be a Roman citizen, and previously, anyone not a citizen could only join the army as an auxiliary. It is possible that with his military goals in Germania, and perhaps for other campaigns to come, Caracalla was seeking to bolster Rome’s military, though his father had done that to a large extent already.

Lastly, we cannot ignore the possibility that the Constitutio Antoniniana may partly have been a play for popularity by Caracalla. With rumours of his brother’s murder circulating, he needed to win some popular appeal, and so this grand gesture of granting citizenship would have – he probably hoped – ingratiated him to those outside of Italy, while perhaps the increased tax revenues might have won him some support within the Italian peninsula.

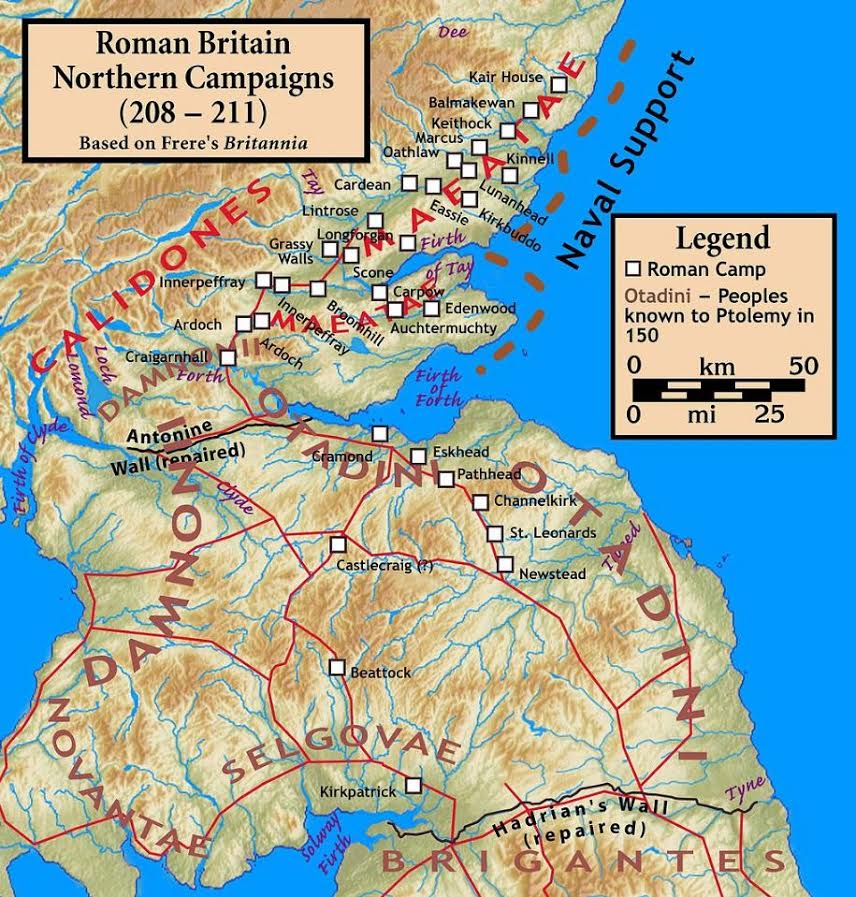

Even people on the edge of the Empire were affected by the Constitutio Antoniniana.

Strangely enough, there is not much mention of the Constitutio Antoniniana, no great commemoration of the event. Why is that?

One reason may be that Caracalla was simply not liked. Certainly, contemporaries such as Cassius Dio, our main source for the period, did not like him and would never sing his praises.

Another possibility for the silence around the creation of the Constitutio Antoniniana could be that its effects upon the Empire left a lot to be desired.

What then were the effects of this important legislation on the Roman world?

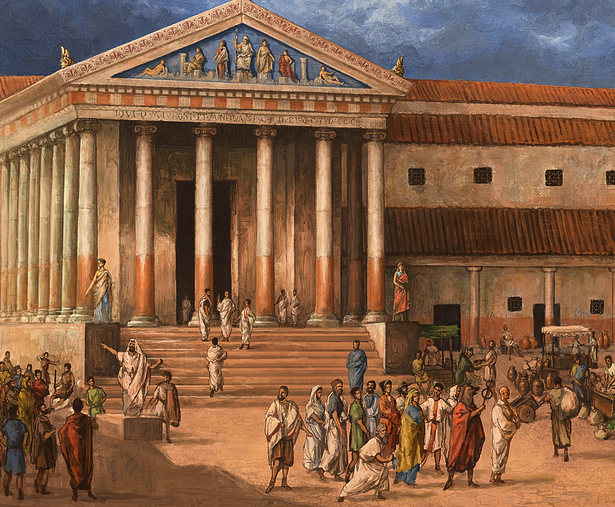

Certainly for many, Roman citizenship would have been a boon, for it had always been a prized possession. For a provincial being granted equal status to an Italian, it would have seemed a good thing on the surface. Certainly, it had a levelling effect in the law courts where the law treated citizens differently to non-citizens.

Increased taxation, however, would have been a bitter pill to swallow for anyone, and this would not have been welcomed.

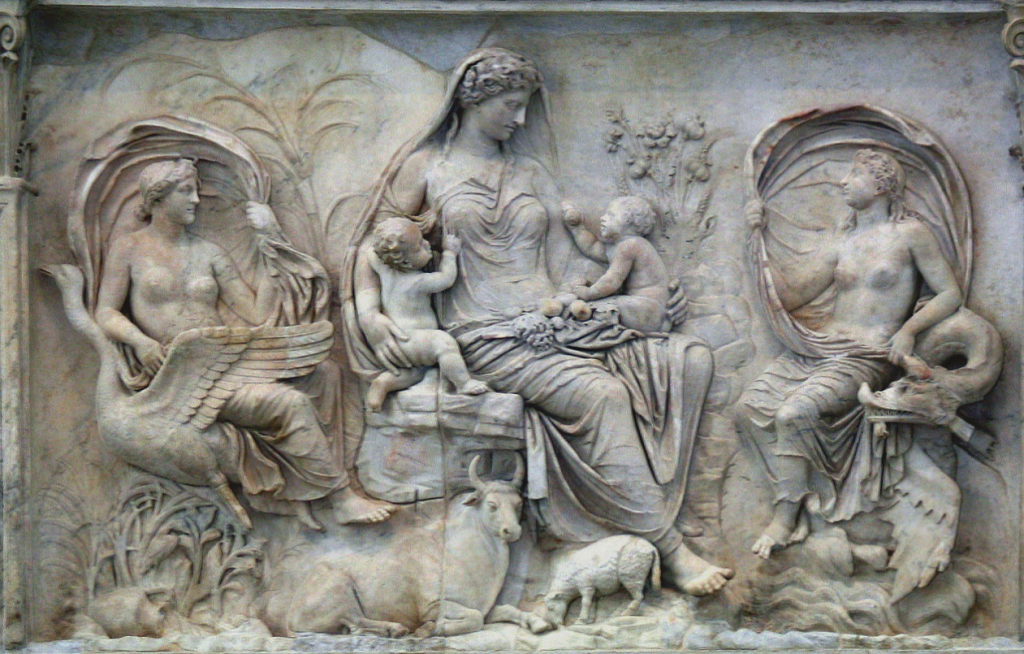

A relief thought to portray Roman tax collectors

When it comes to the military which Caracalla and his father so relied upon, the Constitution Antoniniana did increase the pool from which Caracalla could recruit legionaries, but there was a negative side to this as well.

It now became harder to attract ambitious people into the army, because now all soldiers were citizens. The non-citizen auxiliaries that made up the important cavalry alae, forces of archers, slingers and others, now ceased to exist. There were still native formations of numeri, but the army was permanently changed and now, being open to all, the desirability of being a Roman legionary was fast dwindling.

Lastly, by granting citizenship to all freeborn people across the whole of the Empire, Roman citizenship itself was now cheapened by the Severans’ equalizing tendencies. Citizenship had its privileges, including access to higher civilian and military offices. Now, however, this was greatly watered down, and the few who previously possessed citizenship would now have to compete with many more for prized positions.

This is perhaps one of the greatest impacts of the Constitutio Antoniniana. With the loss in status of citizenship over the following years after A.D. 212, a new elite began to evolve. It was no longer about citizens and non-citizens, or Romans vs. provincials. Rather, class distinction came to the forefront across the Empire with the formation of the honestiores and humiliores classes. Eventually, this class distinction became law, and where honestiores enjoyed legal privileges, the humiliores suffered more severe punishments. It is almost as if the entire Empire was regressing to the time when there was division among Patricians and Plebeians in Republican Rome.

When one reads this, it is hard not to wonder whether such class distinctions are a natural human state or tendency, but that’s a debate for another time.

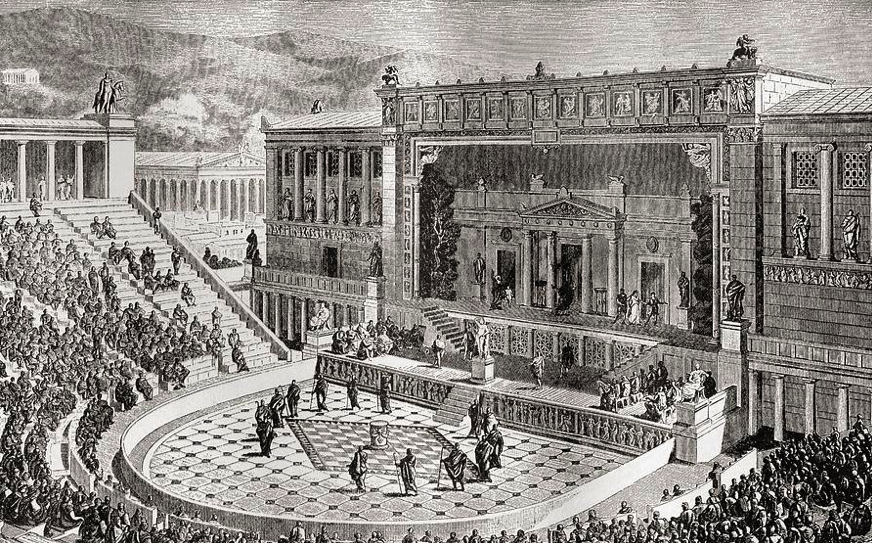

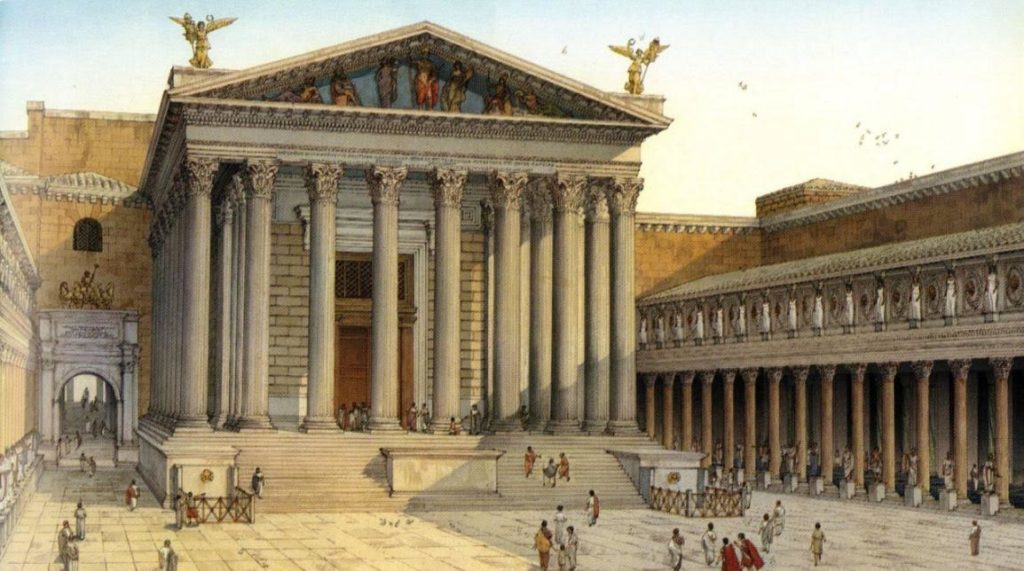

Debate in the Senate over the Constitutio Antoniniana must have been furious. (Senate scene from the movie Fall of the Roman Empire, 1964)

I can’t help but admire – in an idealistic, and perhaps naive way – the equalizing goals of the Constitutio Antoniniana. After all, isn’t that something we are still striving for today? It is often at the heart of many modern political debates.

However, it is difficult for us – as it was, I suspect, for Caracalla’s contemporaries – to get past the man that Emperor Caracalla was, and the actions he had taken at the outset of his reign. He had proved himself to be cruel and spiteful. He was not a good emperor. And so, it is possible that anything ‘good’ that he might have attempted was probably lost behind a scrim of blood.

Despite its strong democratic note, the Constitutio Antoniniana is also believed, by some, to be one of the causes for the degeneration of the Roman Empire.

What do you think? Let us know in the comments below.

Tune in for Part IV in The World of The Blood Road when we will be looking briefly at the Praetorian Guard and the Castra Praetoria, in Rome.

Thank you for reading.

The Blood Road is available on-line now in e-book and paperback at major retailers. CLICK HERE to get your copy. You can also purchase directly from Eagles and Dragons Publishing HERE.

If you are new to the Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series, you can check out the #1 best selling prequel, A Dragon among the Eagles for just 1.99 HERE.