What does it take to make a real Hero? In this vast world filled with mortals, what makes one stand out in the eyes of the Gods?

These questions are not new. They’ve been explored in storytelling for millennia. They have inspired us and guided us, and forced us to take an honest look at ourselves.

The stories in mythology are not just about entertainment, they are about teaching, about bettering ourselves and preparing each of us for our own ‘Hero’s Journey’ through this life.

We’ve all been tested these last couple of years through the modern plague we are enduring and, I suspect, we’ve all had to take a good look at ourselves, our purpose, and the lives we lead. It’s not easy, to be sure, but such introspection is essential to our survival.

In a way, we are, each of us, the hero in our respective stories.

Which leads me to the story of a hero from Greek and Roman Mythology: Bellerophon.

Last week, Eagles and Dragons Publishing launched the fourth book in the Mythologia fantasy series, The Reluctant Hero: The Story of Bellerophon and the Chimera.

In this short post, we’re going to take a brief look why I wanted to re-tell this particular myth, as well as discuss the research that went into bringing it to life in this new, full-length novel in the series.

Bellerophon and the Chimera

SPOILER ALERT!

If you plan on reading, or have not yet finished The Reluctant Hero, you may wish to finish the book before reading this blog post…

The myth of Bellerophon and the Chimera is one that I have been wanting to explore for some time, not only because it provided an opportunity to tell the story of a good old ‘monster battle’, but also because it involved the winged horse, Pegasus.

When I was a child of about six, my first taste of Greek Mythology was seeing the original Clash of the Titans film, and every time I watched it, Pegasus was always the focus of my attention. I loved seeing Pegasus, and wished for such an ally and friend. It was Pegasus who brought me to Bellerophon, though at first I had only associated him with the hero Perseus.

Fresco of Bellerophon, Pegasus and Athena from Pompeii (Wikimedia Commons)

It is strange that most people will know the myth of Perseus, but have only a passing knowledge of Bellerophon, mainly as it relates to the Chimera, and not the man himself. In truth, Bellerophon is one of the central heroes of Greek Mythology, but we seem to have forgotten about him somewhat in the modern age. Perhaps this is due to the film that I, like so many, enjoyed as a child? Popular culture is a powerful thing in the modern age.

I thought it was time to give Bellerophon his due, and the Mythologia series was the perfect place to do it.

When it comes to the Greek myths, the primary sources are often sparse and scattered, our knowledge of them pieced together through fragments of text, artwork, and retellings by Roman writers in later centuries.

Many ancient writers mention Bellerophon and the Chimera, such as Hesiod (Theogony), Pindar (Olympian 13; Isthmian 7), Euripides, and Apollodorus. However, the earliest mention of Bellerophon comes from Homer in the sixth book of the Iliad in which, Glaucus, the grandson of Bellerophon, tells others of his lineage and the story of his grandfather and the Chimera. It is actually quite a long description of the tale, which is a blessing for later writers and ourselves. Interestingly, the description of Bellerophon’s tale by Homer is the first and only mention of actual writing in the Iliad. In reference to the letter that King Proetus has Bellerophon carry to King Iobates of Lykia, Homer writes:

To slay him he [King Proetus] forbare, for his soul had awe of that; but he sent him to Lycia, and gave him baneful tokens, graving in a folded tablet many signs and deadly, and bade him show these to his own wife’s father, that he [Bellerophon] might be slain.

(Homer, Iliad, Book 6, 170)

The sources are varied to be sure. Homer speaks of Bellerophon fighting and defeating the Solymi, the Amazons, and the Chimera, but makes no mention of Pegasus. However, Hesiod does mention that Pegasus and Bellerophon both defeated the Chimera who was the offspring of Typhon and Echidna, and the sibling of Cerberos (the three-headed hound of Hades), and the Lernaean Hydra which Herakles later defeated. It is a fascinating, and sometimes difficult, process to link together the various traditions of a particular myth to create a coherent story, but I believe it has worked in the case of Bellerophon and the Chimera.

The Chimera of Arezzo

Some readers may notice that, for the purposes of the story I wanted to tell, I have changed the order of Bellerophon’s tasks. In Homer, for instance, Bellerophon first slays the Chimera, then fights the Solymi, and finally, defeats the Amazons. Because I wanted the Chimera to be the climactic battle, I thought that it was acceptable to change this order. However, the battle with the Chimera did not end up being the primary focus of this book. Originally, as mentioned above, I had the idea of writing a ‘monster-battle’ novel, but as often happens, things changed as the story developed. At its heart, Greek Mythology is often about very human trials and emotions. To me, though the battle with the Chimera is the climax of the book, the main focus is Bellerophon’s journey from a shadowy no-one to a true hero as he overcomes his own demons and finally discovers himself.

Map showing location of Corinth, Argos and Tiryns

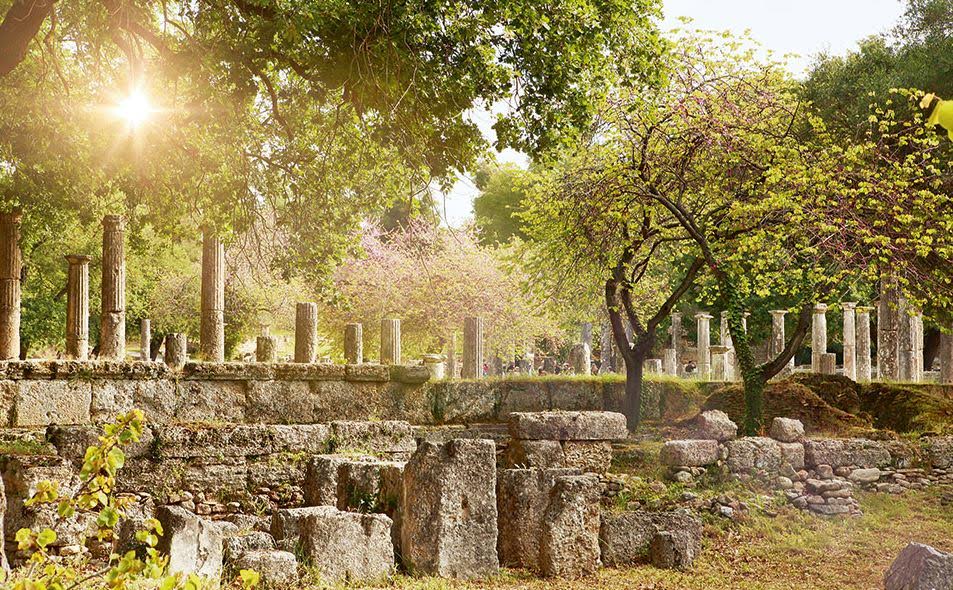

As usual, I have also tried to set the story in the real-world locations in which it was said to have taken place. I have opted to use the name of Bellerophon’s home of Corinthos (Corinth) because it is familiar to us today, but in the ancient texts, and at that time, it was known as Ephyra. I visited ancient Corinth on my first trip to Greece many years ago and remembered being overwhelmed by it, but also saddened at the destruction wrought by Rome on that great and ancient city. It was then that I visited the Acrocorinthos, the enormous mountain that overlooks the city.

Ancient Corinth and the Acrocorinthos (Photos: A Haviaras)

Today, all one sees on the Acrocorinthos are the remnants of the vast medieval castle, but it was not difficult to imagine the place during the Greek Heroic Age. To stand up there and look down on Corinth and the sweeping beauty of the lands south toward Mycenae and Argos over the mountains is, simply-put, breathtaking. I decided to make that the place where Bellerophon’s story begins, where he trains and commits the act that gets him banished from his home, specifically the killing of Belleros which gives Bellerophon his name, ‘Belleros Killer’.

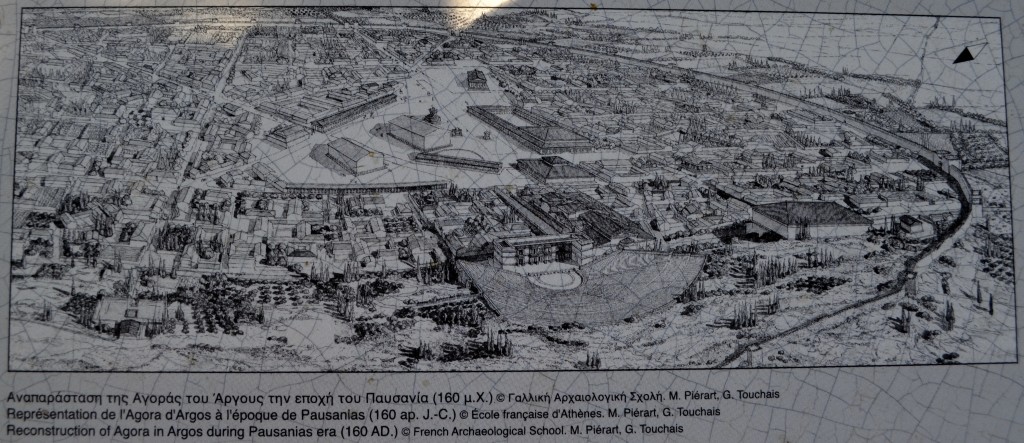

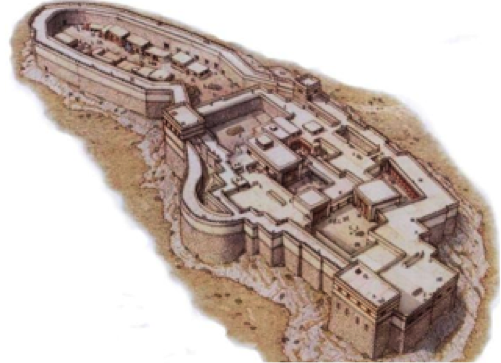

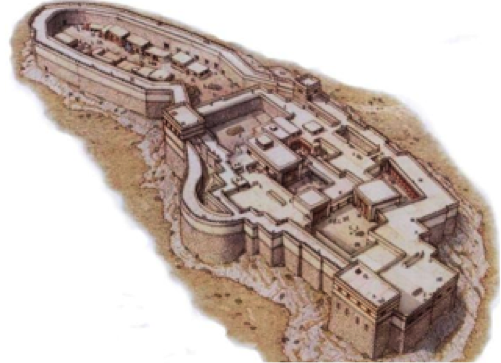

There are other sites in the first part of the tale that you might be familiar with, such as Argos, and the great fortress of Tiryns where Bellerophon stays with King Proetus and Queen Stheneboea (also known as Anteia). Having visited those sites, it was a joy to go back to them and write about the landscape and palace of Tiryns especially. To read more about Tiryns, that ancient fortress of myth and legend, you can read a blog post about my visit HERE.

Artist Reconstruction of the Citadel of Tiryns

Another ancient site that is truly fascinating is the guardhouse where Bellerophon first meets King Proetus’ men. I located this guardhouse at the mysterious Pyramid of Hellinikon, just outside of Argos. This site is believed to be either a tomb, or a guardhouse built during the wars between Proetus and his brother, Acrisios. You can read about the pyramid and watch a short video tour of the site HERE.

The Pyramid of Hellinikon near Argos

Once Bellerophon journeyed across the sea, I was in uncharted territory for myself, never having travelled to modern-day Turkey where the ancient Kingdom of Lykia is located. The research for this was fascinating.

Map showing where parts of The Reluctant Hero take place

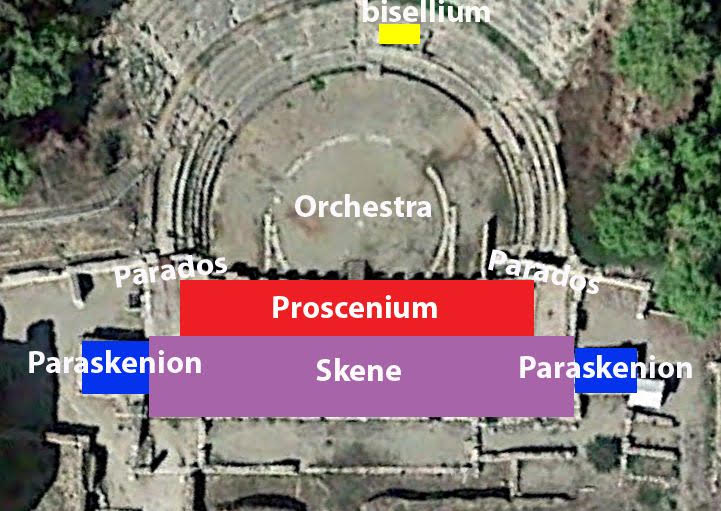

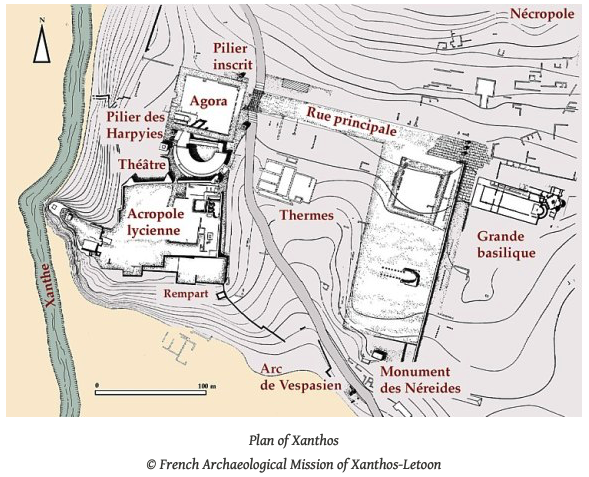

Not far from the Greek islands of Rhodes and Kastellorizo is the mouth of the river Xanthos which leads north a short distance to the ancient city of Xanthos (outside modern Kinik). This ancient Greek and Roman city had many structures such as a theatre, agora, monuments and shrines, as well as unique ‘pedestal tombs’, but there is very little in the way of remains for the period in which this story takes place. There was an acropolis overlooking the river below, and that is where I chose to set King Iobates’ palace in the story.

Likewise, I elaborated on the fictional village of the Solymi where Bellerophon fights the leader of their tribe, though their lands were located in the ancient region known as Pisidia.

When it comes to the Amazons, I chose to set their capital in Phrygia since it was said that there were Amazon tribes in that remote region north of Lykia. In searching for a geographic setting, I chose the ancient city of Hierapolis which is located at modern Pamukkale, known for its mineral-rich thermal waters flowing down white travertine terraces on a nearby hillside. This was a sort of ancient spa town, but for the purposes of this story, I decided to make it the Amazon base.

The hot springs at Pamukkale,Turkey, in ancient Phrygia.

In Turkey today, there is a place known as Mount Chimera, and this is located near the sea to the southwest of Xanthos. Though I chose to make this a remote mountain region to the northeast in the story, I did try to remain true to the setting, mainly the Chimera’s cave and the strange fires that are constantly burning from out of the rocky earth in that place. These are in fact methane gas emissions that are on fire, and have been for centuries, but for as long as people can remember, they have been called ‘fires of the Chimera’. It is here that the climactic battle in the story takes place.

The Cave and Fires of the Chimera (Lykia) (Wikimedia Commons)

Lastly, there is a bit of a nod to my own heritage at the end of the book when Bellerophon and Polyidus meet on the island of Chios, where the paternal side of my family comes from. The reason I chose to do this is because on the island, just north of Chios town, near the sea, is a site known as ‘Homer’s Rock’ or ‘Daskalopetra’. In Greek, daskalos means ‘teacher’, and it was said that Homer himself used to sit upon this rock and tell his tales of the Trojan War and of Odysseus’ travels. This was my acknowledgment of that tradition.

Daskalopetra – Homer’s Rock (Chios, Greece)

One of the most difficult tasks of writing this story was figuring out the family tree and timelines for the characters inhabiting the story. I soon realized that with so many references over time to various characters, it is not as clean-cut as one might think. One question I wrestled with was whether Perseus lived before or after Bellerophon, for the latter dealt with King Proetus whose brother was King Acrisios, the father of Danae, Perseus’ mother. Another question was, which Amazon queen was alive when Bellerophon faced the Amazons. At first I thought it would be Myrina, who was supposedly a friend of Horus (yes, the Egyptian Horus), but then I read that Queen Otrera was the mother of both Hippolyta and Penthesilea. However, Otrera is also said to be the very first Amazon queen. It is all a bit confusing for the modern reader and researcher, but when I decided not to cling to an absolute timeline, the story began to take shape beautifully.

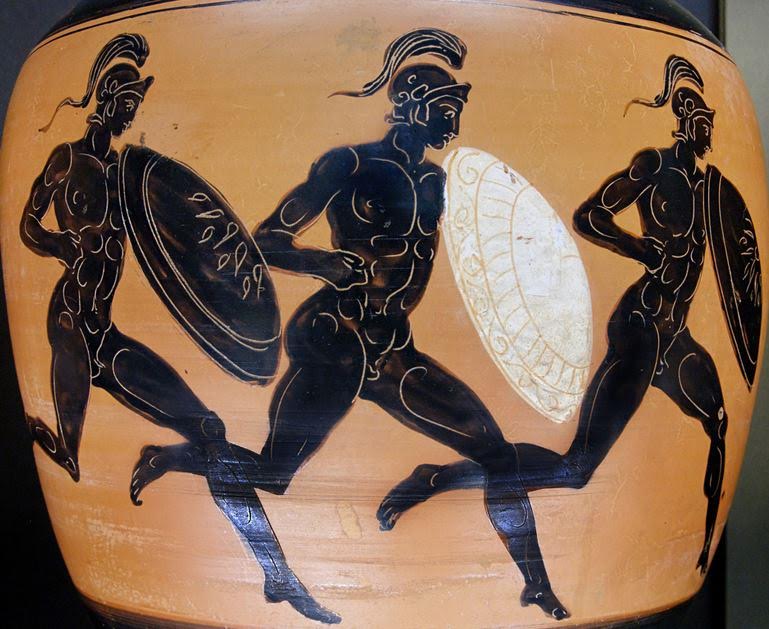

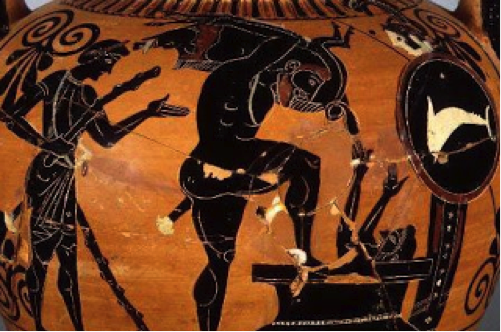

Amazon Warrior (depiction c. 500 B.C)

In mythology, Bellerophon’s parents are Eurymede (sometimes known as Eurynome) of Megara and Glaucus, the son of Sisyphus who founded Corinth and who was one of the great sinners the Gods imprisoned in Tartarus for all time. Mythology does indeed tell us that Glaucus was eaten by his own horses after losing the chariot race at the funeral games of Pelias, and this trauma haunts Bellerophon in this version of the story.

As I have mentioned, King Proetus of Tiryns was the brother of King Acrisios of Argos, and he was married to Stheneboea of Lykia, the eldest daughter of King Iobates, who did send troops to help Proetus in the war against his brother.

King Iobates is one of the main characters in the myth, and in this story, but as is often the case in ancient texts, the women who were a part of the tale get little mention. I wanted to change that with The Reluctant Hero.

This allowed me to delve further into Philonoe’s character (the daughter of King Iobates) as I wanted to bring her to the fore. To me, she languished in the background in the primary sources. The story is, I feel, much more interesting for it, and for the fact that she is not a damsel in distress, ‘saved’ by the hero who shows up. In this story, Philonoe is a hero in her own right.

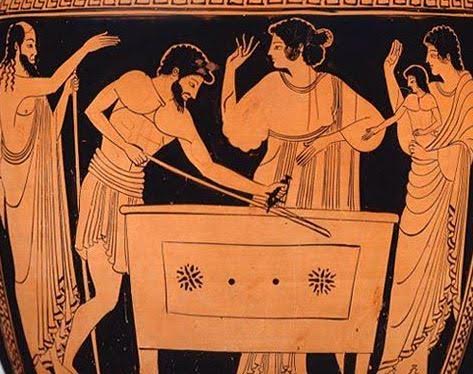

4th Century Mosaic Fragment showing Philonoe and Bellerophon (photo: Barbara McManus)