Arthurian

In Insula Avalonia – Camelot: The Fortress of Arthur

At the very south ende of the chirche of South-Cadbyri standith Camallate, sumtyme a famose toun or castelle… The people can tell nothing ther but that they have hard say that Arture much resorted to Camallate. (John Leland, Royal Antiquary, 1532)

Happy Holidays everyone!

Hard to believe we’re at the end of yet another year. How can so much happen in so little time? With time speeding by at such an alarming rate, History is, as ever, my anchor and touchstone.

This will likely be my last post of 2014. When I was trying to think of a suitable topic, it didn’t take me long to decide what better way to get into the holidays than a post about ‘Camelot’.

We haven’t been In Insula Avalonia since the springtime when I spoke about Glastonbury Abbey, and prior to that Gog and Magog, Wearyal Hill and the Holy Thorn, The Chalice Well, and Glastonbury Tor. If you missed those posts, you can read them on the old website. Just click on the names.

For Part VI of In Insula Avalonia, we’re going to look at a site that is just ten miles from Glastonbury itself: South Cadbury Castle.

Now, South Cadbury Castle, like so many of the other places that we have discussed in this blog series, is a site with strong Arthurian associations. As such, its importance and role is hotly debated.

Was South Cadbury Castle the power centre of the historical Romano-British warlord, or dux bellorum, we know as ‘King Arthur’? Was this the actual site of what has come to be known in the popular imagination as ‘Camelot’?

I’ve always been a strong proponent of the theory that there was in fact, an historical ‘Arthur’ who formed the factual basis for all the legends we love and cherish. So, when I look at sites such as South Cadbury, I do so with that in mind. However, that doesn’t mean that I accept a site’s association with Arthur on faith alone.

I know this site pretty well – as I studied it and wrote about it as part of my Master’s dissertation entitled Camelot: Comparing the historical, archaeological, and toponymic evidence for King Arthur’s Capital. As part of this, I looked at three of the main candidates for Camelot that had been put forward at the time – Wroxeter (Roman Viroconium), Roxburgh Castle (in the Scottish Borders), and South Cadbury. There is a copy of the dissertation hidden somewhere in the stacks at the St. Andrews University library in Scotland.

South Cadbury Castle is also where I cut my teeth as an archaeologist as part of the South Cadbury Environs Project team for a couple of seasons under the leadership of Professor Richard Tabor. This was a wonderful experience that helped me to get up close and personal with the site I had studied for so long – I dug test pits, got into bigger trenches in which curious cows came to watch what I was doing, carried out geophysical surveys with a magnetometer, and found some curious objects such as a bronze dolphin that formed the handle of a Roman drinking cup.

Most of all, I was given the chance to spend more time on this amazing, and yes, magical, landscape.

Before I give my thoughts on wandering the slopes of South Cadbury Castle, we should have a look at what it actually is.

South Cadbury Castle is not the late medieval castle with banners flying from tall towers that make up our usual image of Camelot. It is a 500 foot high Iron Age hill fort located in the pre-Roman era lands of the Durotriges. Occupation of the site began in the Neolithic period and it went through various stages of occupation from the 5th century B.C. onward.

By the time of the Roman invasion of Britain, it had four massive defensive ramparts with an inner area of about 18 acres. Access to the top was by two entrances, one to the north-east and the other, larger one to the south-west. The Iron Age occupation of the site came to a violent end around A.D. 43 when Vespasian stormed the southern hill forts of Britannia.

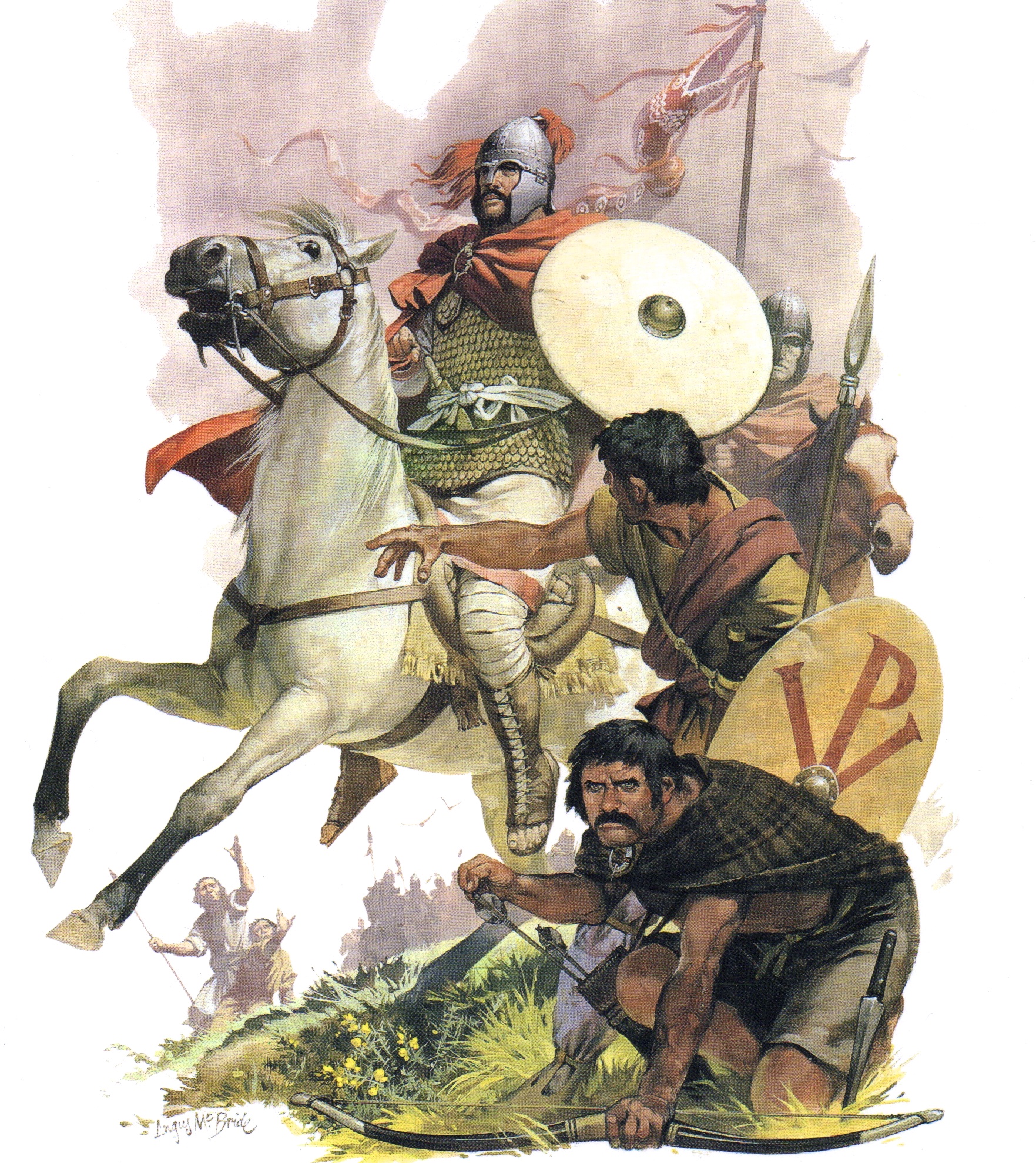

British Belgic Warriors of the Iron Age – Illustrated by Angus McBride (source – Rome’s Enemies 2 – Gallic and British Celts)

The Romans made little use of the site, though there have been some theories that it was used as a Roman supply station.

In the 3rd and 4th centuries, there was renewed activity with visits being made to a Romano-Celtic temple that was built on the site. During excavations, a bronze letter ‘A’ was found that some believe belonged to this temple, which was perhaps dedicated to Mars, or some other deity.

However, when it comes to South Cadbury Castle, the period that I am concerned with is the 5th and 6th centuries A.D. This period is known as the ‘Arthurian’ period, and it is at this time, after Rome’s legions have left the island, that the archaeology shows a massive refortification of the hill fort.

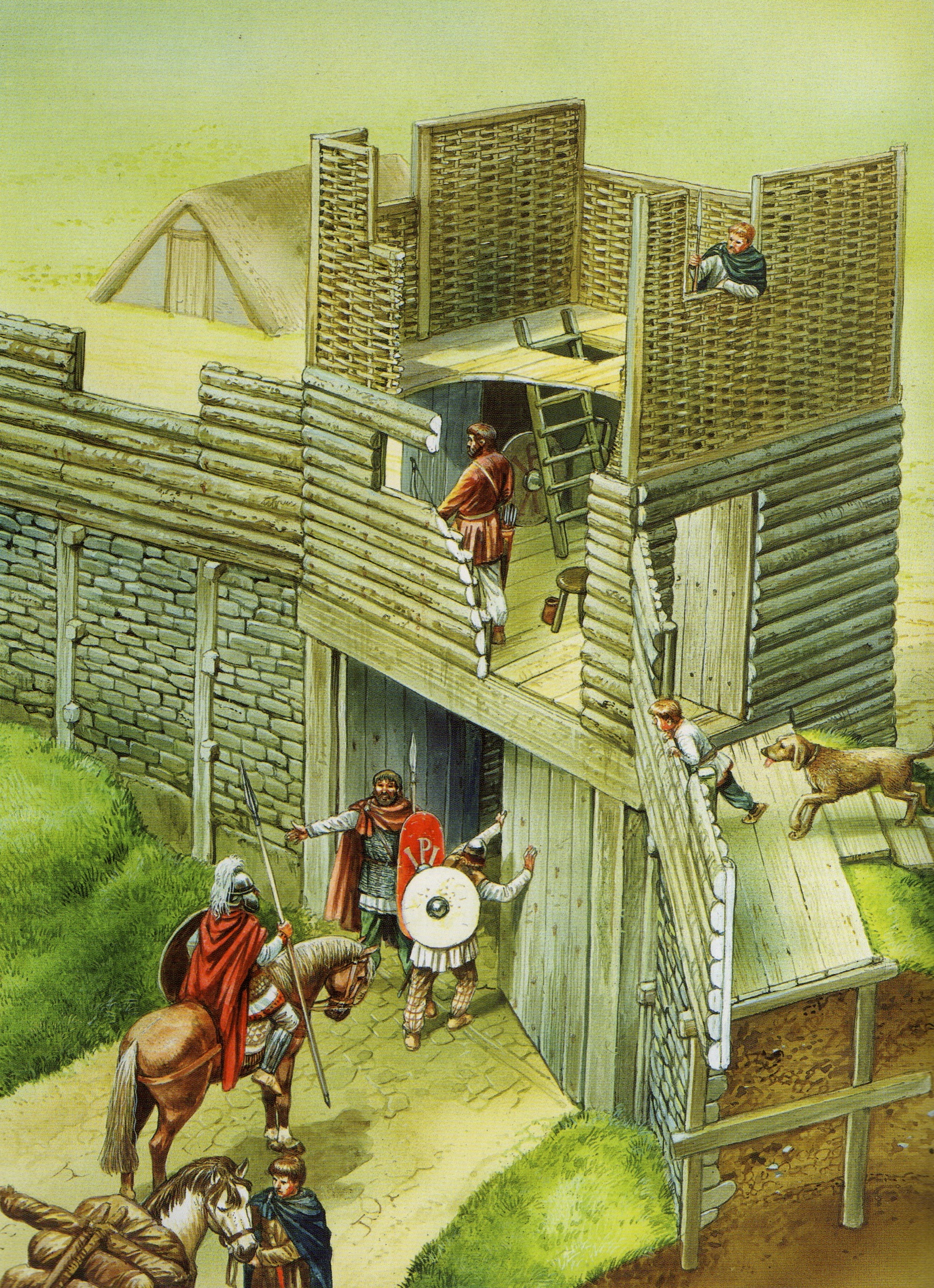

Artist Reconstruction of South Cadbury Hill Fort – Illustrated by Peter Dennis (Source- British Forts in the Age of Arthur)

Though it is much debated, South Cadbury’s association with the Arthurian period stems not just from hearsay and folklore. It has the archaeological evidence to back it up.

There have been a few big excavations of the hill fort over the years, but the biggest of all took place in the late 1960s and was headed by Professor Leslie Alcock. Professor Alcock and his team discovered evidence for a large scale occupation and refortification of the hill fort, during the Arthurian period, which showed repaired defences, including a strong gatehouse at the south-west entrance, and most importantly, several buildings, including a kitchen and a large timber hall on the fort’s high plateau.

The discovery of post holes reveals a finely-built timber hall that was on a large scale, measuring about 63×34 feet. This hall would not have been the great castle hall of late medieval romance, but rather something like the timber drinking halls of the period, more like to the Golden Hall of Meduseld, the seat of King Theoden in Lord of the Rings.

Another very telling discovery at Cadbury Castle was the large quantity of Mediterranean pottery that dates to the Arthurian period of occupation. This is the same pottery type that was discovered at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall, a site that also has strong Arthurian associations. One might think that shards of pottery from wine, olives and olive oil might be pretty mundane, but they anchor the sites strongly in the period, and also show that someone of importance was associated with the site. Not everyone could afford to import such things through trade.

6th Century British Warriors – Illustrated by Agnus McBride (source – Arthur and the Anglo-Saxon Wars)

The refortification of the hill fort during the Arthurian period was on a massive scale, and would have required many resources and men to hold it. South Cadbury castle was, in a way, on the front lines of the British struggle against the invading Saxons, and would have been well-placed to meet the Saxons as they advanced westward.

Based on the refortification, and evidence of the gatehouse that linked the ramparts running over the cobbled road at the south-west corner, this place was likely the base for an army that was large by the standards of the period. It may way have been the site of the court of the dux bellorum, or the historical Arthur.

Artist Reconstruction of the South-west gate – Illustrated by Peter Dennis (Source – British Forts in the Age of Arthur)