Have you ever wondered why forests are so often the setting for nightmares?

Think about it. It’s true.

Ready for a fight – a scene from the movie, Centurion

I remember a recurring nightmare that I had when I was a child: I’m in a dark forest, walking by myself. My feet crunch on a carpet of dead leaves in a slow, steady rhythm. Then a second set of footsteps, comes into my hearing, only they’re faster. They’re pursuing me. I begin to panic, and run. I yell but the woods devour my cries. I believe someone is chasing me, and my heart is close to bursting… And then I wake up.

That might not seem scary now, but when you are 6 it’s another story.

Nightmares are fascinating and curious. As a child I didn’t know that the quickening steps of my forest pursuer were really the sound of the blood pulsing in my ear as it pressed into my pillow. Those woods were terrifying to me.

The Forests of Germania

Think about the woods again. How many of you have read or heard scary stories that take place in a forest? For ages, the woods or any kind of forest, have been shadow realms of the unknown, places of magic and nightmare, of beasts and death.

But there is a reason why forests have become such monsters in and of themselves. Not all tales of horror in the woods are fabricated by active, childish minds.

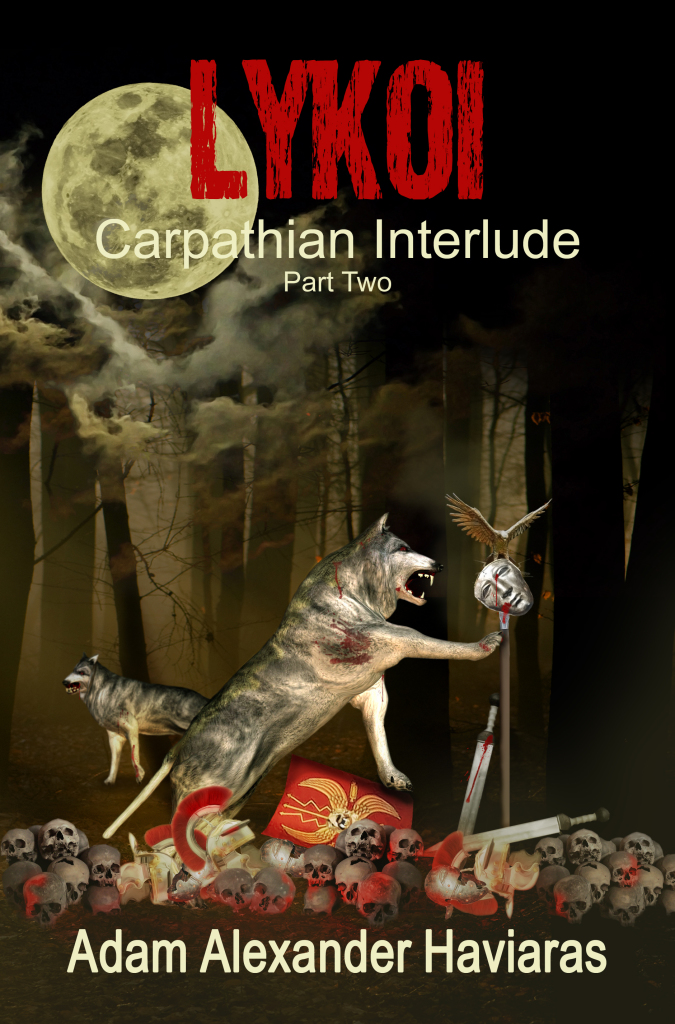

The Carpathian Interlude series revolves around a particular event in Roman history known as the Varus Disaster. It took place in A.D. 9, during the reign of Emperor Augustus, and it was truly the stuff of nightmares.

Public Quinctilius Varus was a patrician Roman general and member of the imperial circle who had been put in charge of the administration of Germania, which had only recently been tentatively subdued by Rome. Varus had previously had success governing provinces in Africa, Syria, and Judea, so it was believed he would be more than capable of handling Germania.

Marching through the Teutoburg Forest

Varus is said to have also had a reputation for being a tyrant who inflicted brutal punishment on the people he was governing and squeezing taxes out of.

It’s safe to say that Varus thought he was quite secure in his position. He was a skilled administrator by Roman standards, had a proven track record, the bloodline to back it up, and a staff of trusted advisors.

Among the people on Varus’ staff was a man named Arminius. Does that name ring a bell?

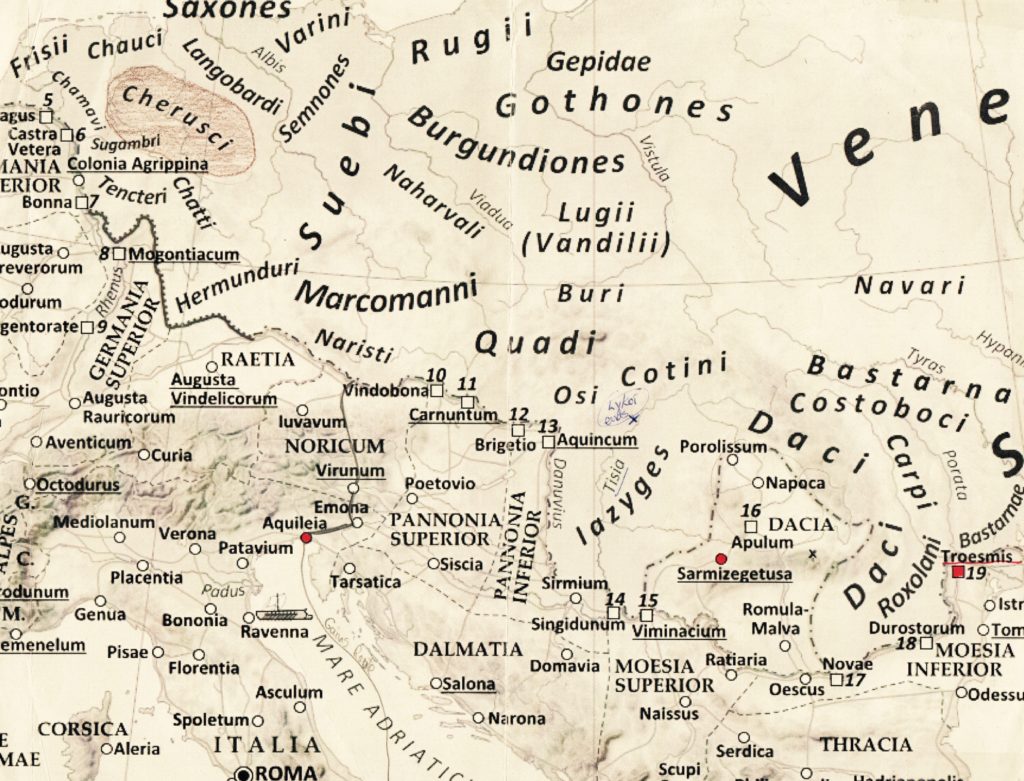

Arminius was the son of Segimerus, the chieftain of the Cherusci, a Germanic tribe that had bent the knee to Rome. As surety for their father’s good behaviour, Arminius and his younger brother Flavus were sent to Rome when they were just boys. We’ll focus on Arminius.

Arminius grew up in Rome, learned the ways of Roman life, and politics, and martial prowess. He began to make a name for himself and was admitted to the Equestrian order to become a cavalry officer.

When Varus was assigned to Germania, Arminius went with him as one of his most trusted advisors and skilled officers. In fact, it’s said that Varus and Arminius regularly dined together; no doubt Varus valued Arminius’ advice in governing the lands of his former people.

This is the seed of the nightmare of which I spoke earlier.

Map used for research and writing of The Carpathian Interlude

In the late summer of A.D. 9, Publius Quinctilius Varus led three legions (the XVII, XVIII, and XIX Legions) deep into Germania to collect taxes and tribute. Varus also had with him six auxiliary cohorts, three cavalry alae, slaves, and camp followers consisting of women, children, merchants and tradesmen. This was a large, slow-moving army. Because they were in a dense forest, the line of march was thin, and stretched over 15-20 kilometres.

But Varus felt he had little to worry about and was so confident that he didn’t event send scouts ahead.

Then Arminius brought word of an uprising to Varus who sent the former to take care of it. Varus was warned against Arminius by another German advisor, Segestes, who was actually a relative of Arminius. But Varus ignored Segestes’ warnings not to trust Arminius and so the nightmare really began.

Rather than supressing the uprising, Arminius instead disappeared into the forest to rally the allied Germanic tribes and attack the Roman forces.

The mountains had an uneven surface broken by ravines, and the trees grew close together and very high. Hence the Romans, even before the enemy assailed them, were having a hard time of it felling trees, building roads, and bridging places that required it. They had with them many wagons and many beasts of burden as in time of peace; moreover, not a few women and children and a large retinue of servants were following them… For the Romans were not proceeding in any regular order, but were mixed-in helter-skelter with the wagons and the unarmed, and so, being unable to form readily anywhere in a body, and being fewer at every point than their assailants, they suffered greatly and could offer no resistance at all. (Cassius Dio, The Roman History 20)

I thought my nightmare in the forest was horrifying.

Artist impression of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest

For three days the Romans were ambushed by the Germanic tribesmen. Three days in the tangle of the Teutoburg Forest, the bogs and brambles, the rivers, and marshes, violent storms and…the dark.

Varus, the legions, and the camp followers had no chance. Arminius had learned how Romans fought, how to weaken them, and how to defeat them. He had laid his plans well, and after three days of desperate fighting, the Romans may have made their last stand at a place known today as Kalkriese.

In the end, Varus and some of the other officers took their own lives rather than fall into the enemy’s hands. Perhaps, as well as fear, it was Varus’ shame that let him to do such a thing. The total number of Roman dead? – about 20,000.

… three legions were cut to pieces with their general, his lieutenants, and all the auxiliaries… they say that he [Augustus] was so greatly affected that for several months in succession he cut neither his beard nor his hair, and sometimes he would dash his head against a door, crying: “Quinctilius Varus, give me back my legions!” And he observed the day of the disaster each year as one of sorrow and mourning… (Suetonius; Life of Augustus 23)

There is no mistaking that this was indeed a real-life nightmare for Rome, and this crushing defeat struck fear into the hearts of everyone from the lowest Suburan sewer rat right the way up to Augustus himself.

Kalkriese – the possible site of the Legions’ last stand

Years later, when Germanicus went into Germania to find the remains of the fallen legions, he came to the site of the struggle.

…they [Germanicus and his men] visited the mournful scenes, with their horrible sights and associations. Varus’s first camp with its wide circumference and the measurements of its central space clearly indicated the handiwork of three legions. Further on, the partially fallen rampart and the shallow fosse suggested the inference that it was a shattered remnant of the army which had there taken up a position. In the centre of the field were the whitening bones of men, as they had fled, or stood their ground, strewn everywhere or piled in heaps. Near, lay fragments of weapons and limbs of horses, and also human heads, prominently nailed to trunks of trees. In the adjacent groves were the barbarous altars, on which they had immolated tribunes and first-rank centurions. Some survivors of the disaster who had escaped from the battle or from captivity, described how this was the spot where the officers fell, how yonder the eagles were captured, where Varus was pierced by his first wound, where too by the stroke of his own ill-starred hand he found for himself death. They pointed out too the raised ground from which Arminius had harangued his army, the number of gibbets for the captives, the pits for the living, and how in his exultation he insulted the standards and eagles. (Tacitus, Annals 1.61)

People must have thought that the gods had turned their backs on Rome.

So how does this fit with the Carpathian Interlude?

When I think of the nightmare of the Varus disaster, what it must have felt like for the troops and camp followers who knew that the barbarians would kill them at any moment, I feel terror for them. The shock, the surprise, the desperation as people were dying all around them in such horrible ways must have been truly overwhelming.

Death

I wanted to take the terror one step further. What if Arminius had more than just the element of surprise on his side? What if he had allied himself with a darker, more powerful enemy in his desperation to crush Rome and assume hegemony over the Germanic tribes?

This is the path I’ve taken in turning this historic event into historical horror.

Cassius Dio describes the omens that Rome witnessed in the aftermath of the disaster, the fearful belief of Augustus and others that the gods were indeed angry:

For a catastrophe so great and sudden as this, it seemed to him [Augustus], could have been due to nothing else than the wrath of some divinity; moreover, by reason of the portents which occurred both before the defeat and afterwards, he was strongly inclined to suspect some superhuman agency. (Cassius Dio, The Roman History 24)

The Kalkriese Mask – worn by one of Varus’ doomed troops

In the next part of The World of The Carpathian Interlude, we will explore the ancient beliefs that helped to shape the terrible beasts that are ally to the Germanic tribes in the story.

Thank you for reading…