Caledonia

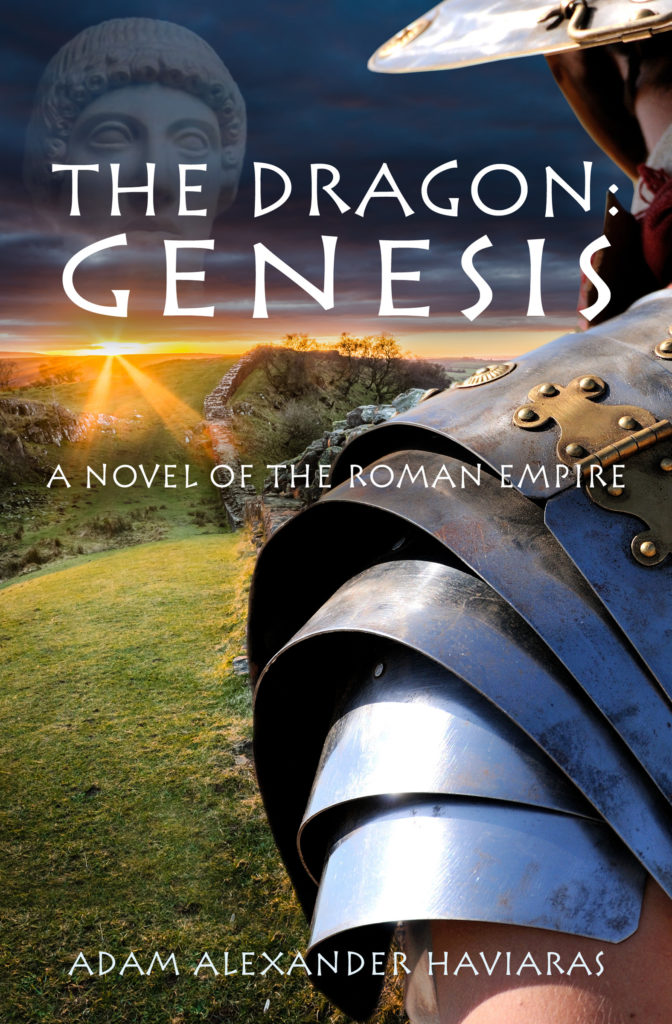

The World of The Dragon: Genesis – Part I – The Antonine Wall

Welcome to Part I of this new blog series celebrating the release of the latest Eagles and Dragons series novel The Dragon: Genesis.

In this blog series, we’ll be sharing the research that went into the novel with you, looking at the history, settings, themes, and historical personages that are related to the story which takes place during the second century A.D.

When we think of the Roman Empire, what often comes to mind is the image of marching legions spreading out over the world. We also conjure images or memories of great ruins on the edges of Rome’s empire such as the massive amphitheater at El Jem in Tunisia, or the ruins of temples and other constructs that dot the European, Middle Eastern, and North African landscapes.

Roman frontiers were vast, stretching thousands of kilometers and encompassing many lands and peoples over time. These frontiers are perhaps what many think of when it comes to the Roman Empire, and none more so than Hadrian’s Wall, the great stone frontier fortification built by Emperor Hadrian in northern Britannia in the 120s A.D. It stretched 73 miles from modern Carlisle to Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and marked a decisive edge of the Roman Empire.

There was, however, another wall.

Approximately 100 miles to the north of Hadrian’s Wall, in modern Scotland, lie the somewhat less romantic, but highly significant, ruins of the Antonine Wall, another frontier of the Roman Empire, and an important cultural and heritage landscape today.

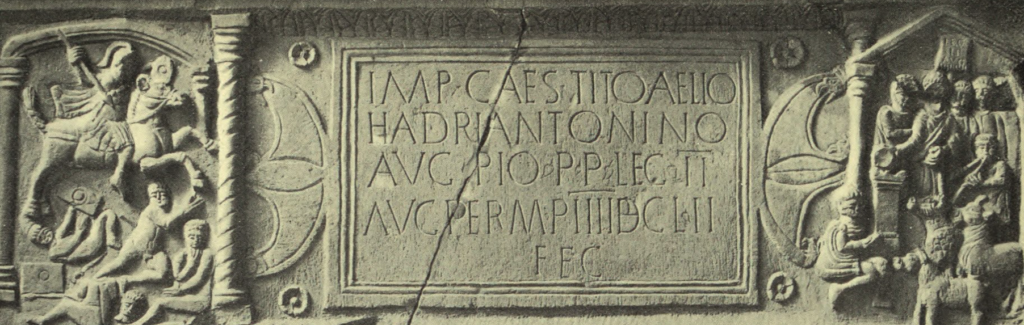

In the early 140s A.D., the emperor Antoninus Pius (A.D. 138-161) ordered a new frontier to be built in Caledonia. It was a massive building project, and the work was undertaken by the men of three legions: the II Augustan from Isca (Caerleon), the VI Victrix from Eburacum (York), and the XX Valeria Victrix from Deva (Chester). Until the forts and fortlets were constructed, the troops would have lived in tents in temporary camps, and among their numbers would have been specialists such as surveyors, masons, carpenters and many more.

At the outset, overall responsibility for the building project was given to the governor of Britannia at the time, Quintus Lollius Urbicus.

The purpose was, perhaps, two-fold: to attempt to push Rome’s permanent frontier father north, but also to hold back the warlike tribe (perhaps a confederation of tribes) we know as the Caledonii.

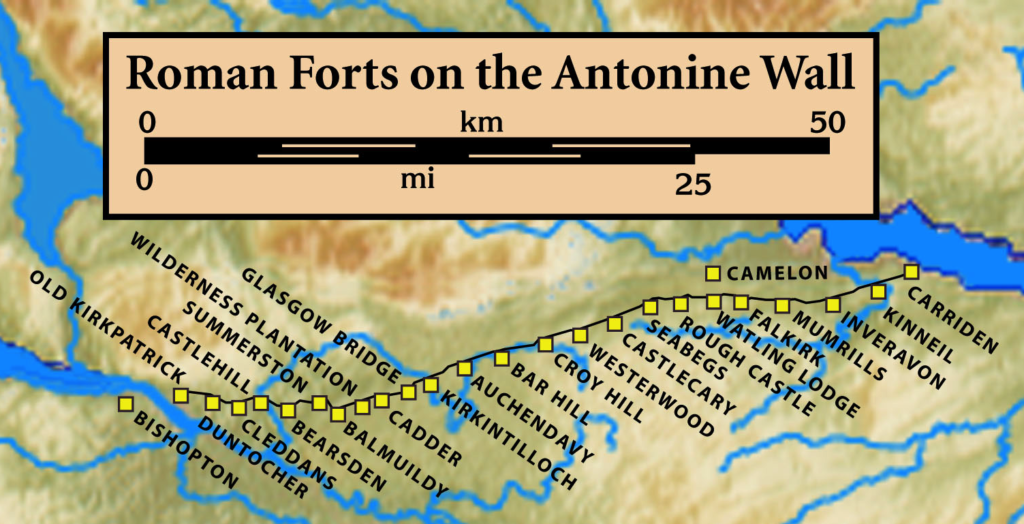

The Antonine Wall may be smaller in scale to Hadrian’s Wall, but it is still an imposing construction. It was 39 miles long, stretching from the Firth of Clyde in the West (near Glasgow) to the Firth of Forth in the East (near Edinburgh). It cinched the belt of Scotland.

But this was not just a wall! It was a manned frontier of the Roman Empire.

The Antonine Wall consisted of about seventeen forts and approximately 9 smaller fortlets every 2 miles, including two coastal forts at either end. The garrison of this frontier was in the range of 6000 to 7000 troops. This included legionaries, but the garrison was mainly comprised of auxiliary troops once the wall was complete.

Despite its importance, why isn’t the Antonine Wall as well-known as Hadrian’s Wall?

Part of the reason for this is that its ruins are less prominent. Less has survived.

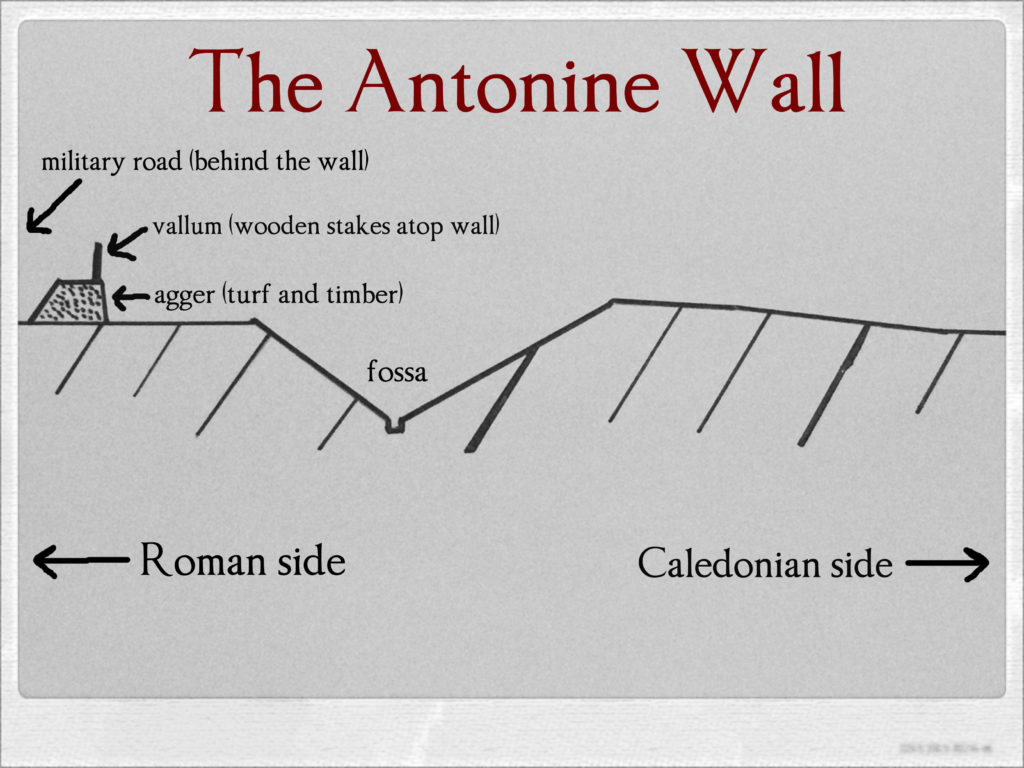

The Antonine Wall was not built of stone on the imposing scale of Hadrian’s Wall. It was a turf and timber wall built on a stone foundation. For this reason, today the remains mostly consist of a grassy embankment, 13 feet high, that was part of the ditch (fossa) located to the north the wall. The wall itself consisted of a turf embankment (agger) topped by a wooden battlement or barricade of sorts (vallum) behind the ditch. You can read more about the specifics of Roman defences HERE.

Unlike Hadrian’s Wall, which had ditches, or fossae, in front and behind, the Antonine Wall had but one fossa in front. It also had a military road running the length of the wall behind it so as to allow for quick, efficient movement of troops and supplies along the way, as well as the relaying of commands and news.

When completed, the Antonine Wall would have been an imposing defensive line in Caledonia. Interestingly, it was not the first such network.

There was a defensive line of forts from the Agricolan invasion of Caledonia in the first century A.D. that pre-dated both Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall. This frontier is known today as the Gask Ridge, and many of the forts along this first frontier were refortified during the Antonine period.

The Antonine Wall joined up with the Gask Ridge frontier roughly at the fort of Camelon, and together, the two frontiers further hemmed the Caledonii in on the highlands.

To read more about the Gask Ridge frontier, which is the setting for the novel Warriors of Epona, CLICK HERE.

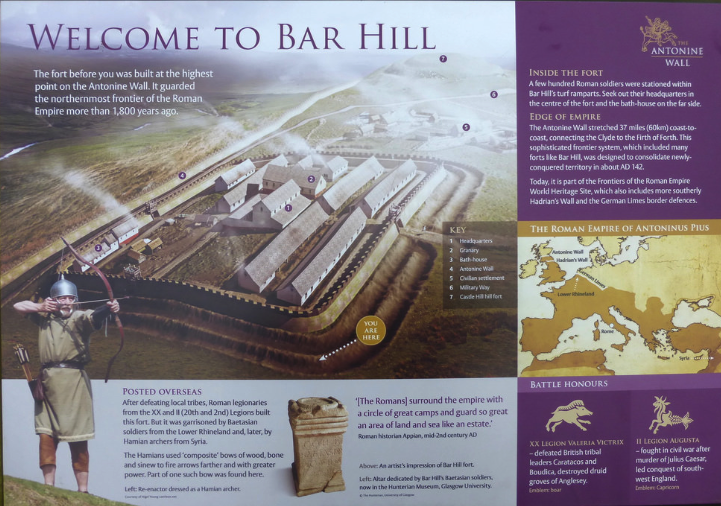

Signage at Bar Hill fort site showing reconstruction of the fort. Bar Hill fort was the highest point along the Antonine Wall.

The novel The Dragon: Genesis begins during construction on the Antonine Wall, specifically at the site of Bar Hill fort which was the highest point of the wall. This fort had commanding views from its vantage point, and it was one of the larger forts along the wall, complete with principia, or headquarters building. It is interesting to note that the fort here was not flush with the wall like some others, but rather was set back, just south of the military road.

The location of this fort made it the ideal place to start the novel.

It is perhaps an attestation to the resistance put up by the tribes of Caledonia that the Antonine Wall was abandoned in A.D. 162, just twenty years after construction began.

It lay in this state of abandonment until about A.D. 208 and the Severan invasion of Caledonia. At that time the Antonine Wall and many of the Gask Ridge frontier forts were re-garrisoned. To read more about the Romans in Scotland, CLICK HERE.

After the two phases of the massive Severan invasion of Caledonia, the Antonine Wall became silent once more, the frontier moving back again to Hadrian’s stone construction.

Today, you can visit the remains of the Antonine Wall on any number of walks to visit the locations of several of the forts listed on the map above, including the fort at Bar Hill. It really is an amazing landscape with many fascinating sites along the way. It’s no wonder that in 2008 it was officially given World Heritage Site status by UNESCO as part of the ‘Frontiers of the Roman Empire’.

To read a lot more about the Antonine Wall and the individual forts that are a part of it, be sure to check out the official website HERE.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this first part in The World of The Dragon: Genesis.

The book is not for sale anywhere, but if you are interested in reading it, you can get a copy for FREE by clicking HERE, or by clicking on the book cover image above.

Stay tuned for Part II of The World of The Dragon: Genesis, when we will be looking at the cursus honorum in ancient Rome.

Thank you for reading.

Oh, Picts!

We’re heading into the wilds of Caledonia in this week’s post.

I wanted to discuss a topic that is often neglected although it is very interesting: the Picts and Pictish art.

As I’ve been packing for a move, I discovered some of my old photos from my days in St. Andrews, Scotland. I came across a packet of prints from an outing with some of my MLitt colleagues to visit Pictish sites in Angus and Perthshire.

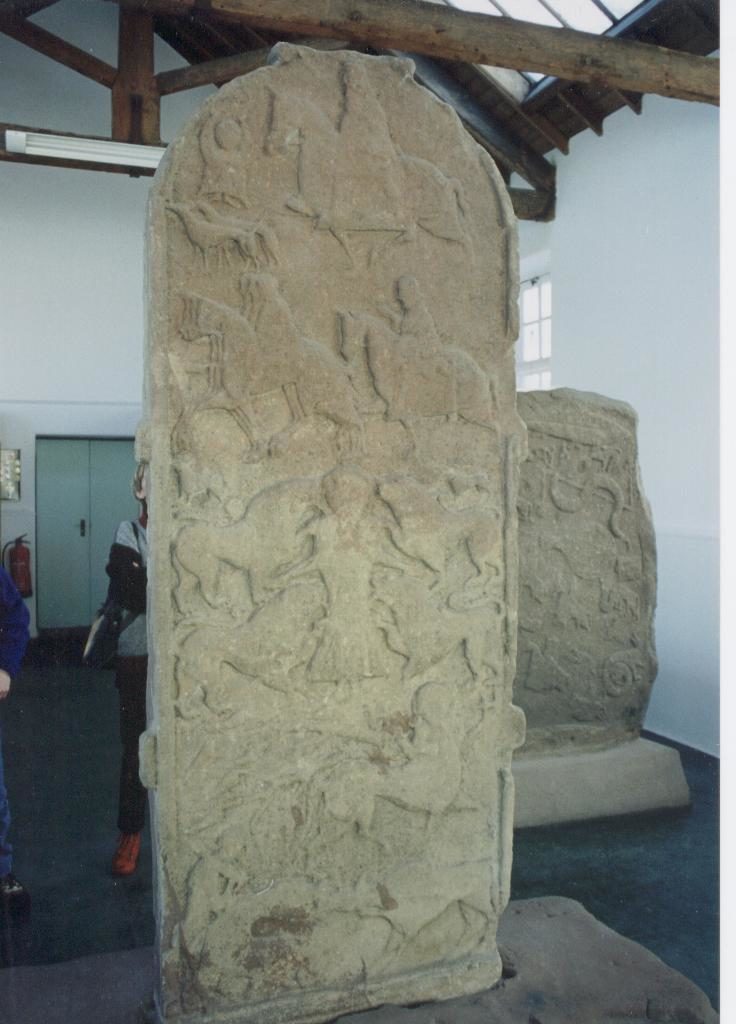

The main attraction for us was the wide array of ornate carvings on several Pictish gravestones, most of which are maintained by Historic Environment Scotland at the Meigle Museum which is itself an old school house on the A94 Coupar Angus to Forfar road (for those of you who are interested in visiting). This little museum is a true gem and well worth a visit.

Before looking at the carvings however, I suppose I should answer one simple (or not so simple) question. Who were the Picts?

In brief, they are the direct descendants of the Caledonii, the blanket name given to those tribes who lived in the lands north of the Firth of Forth.

We hear about the latter in relation to the Roman invasion of what is now Scotland by Agricola in AD 79. The action-packed movie Centurion, with Michael Fassbender, which came out in 2010, deals with Agricola’s operations north of the Firth of Forth and the presumed disappearance of the Ninth Legion. In the film, the Caledonii/Picti are portrayed as a society run by a warrior elite, the members of which paint themselves with blue woad. The film is very entertaining, if not violent, but the best thing is that it was filmed where much of the history presumably took place. It’s worth a gander for that, if anything.

But were the Picts simply a mass of blue barbarians as they’re so often portrayed? Likely not.

Contrary to the usual portrayal, the Picts were not simply one enormous group living and fighting north of the Antonine Wall. They were indigenous Celts and the term ‘Picti’, like ‘Caledonii’ or ‘Maeatae’ is more of a blanket term that included approximately twelve Celtic tribes north of the Forth and Clyde rivers. These were recorded by the Roman geographer Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD. Because of the military threat posed by Imperial Rome, the Celts in the area amalgamated into two larger groups. The Caledonii and the Maeatae and, in turn, came to be later referred to as ‘Picti’.

The tribal federation survived the various Roman incursions (the last one being the Severan invasion of Scotland in the early 3rd century – the setting for Warriors of Epona). As a result the Picts were able to develop mechanisms of kingship and by the 6th century there was a Pictish kingdom.

In Pictish art, there are certain recurrent symbols such as those found on the Aberlemno stone including the ‘serpent’, the ‘double-disc’, the ‘crescent’ and the ‘Z-rod’. When I visited the Meigle museum I was struck immediately by the amount of Christian imagery, having had in my mind typical images of paganism when it came to the Picts. The presence of crosses and other Christian images is due to the conversion of the Picts to Christianity after the Irish abbot of Iona, St. Columba, ventured into ‘Pictland’ in AD 565. Columba met the Pictish king, Bridei son of Maelchon in a fortress near the River Ness and thus began the conversion of the Picts, a process that was complete by about AD 700.

The Pictish symbol stones are one of the most important sources for information about the Picts, and the symbols, common from one end of Scotland to the other, were widely understood by all the tribes. Now, however, we know very little of their actual meaning except that they functioned as memorial stones or territorial boundary markers.

The church yard at Meigle contained a large number of Pictish stones, implying that Meigle was itself a very important centre of burial for the Pictish church and under the patronage of the kings of the Picts. Eventually however, Pictish rule, which had survived the onslaught of Rome in Late Antiquity, was taken over by the Gaelic-speaking settlers of Dalriadia (or ‘Dal Riata’ – modern Argyll) which led to the reign of the Scots King, Kenneth mac Alpin and his subsequent dynasty.

Before we bid farewell to the Picts however, there is an interesting Arthurian connection with Meigle and one of the Pictish stones (cross-slab no.1).

On entering the graveyard at Meigle, there is a grassy mound known as Vanora’s Grave. Local tradition has it that Vanora was actually Queen Guinevere, the wife of Arthur. Vanora was abducted by the Pictish king, Mordred, and held captive near Meigle. When she was returned to her husband after this forced infidelity, she was sentenced to death by being torn apart by wild beasts, hence the scene of Vanora’s death on the back of cross-slab no.1. Her remains were buried at Meigle.

Tradition also says that Vanora (and Guinevere for that matter) was barren and it is believed that any young woman who walks over her grave risks becoming barren herself. True or not, this is yet another interesting anecdote of history and legend.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post. Once more, if you ever get the chance to visit Meigle’s museum and some of the stones in the surrounding area, it’s well worth it.

If Picts are your thing, then you may also wish to take a look at the map and pamphlet of Pictish sites released by the Angus Council by CLICKING HERE.

Thank you for reading!

The World of Warriors of Epona – Part V – Legions in the North: The Romans in Scotland

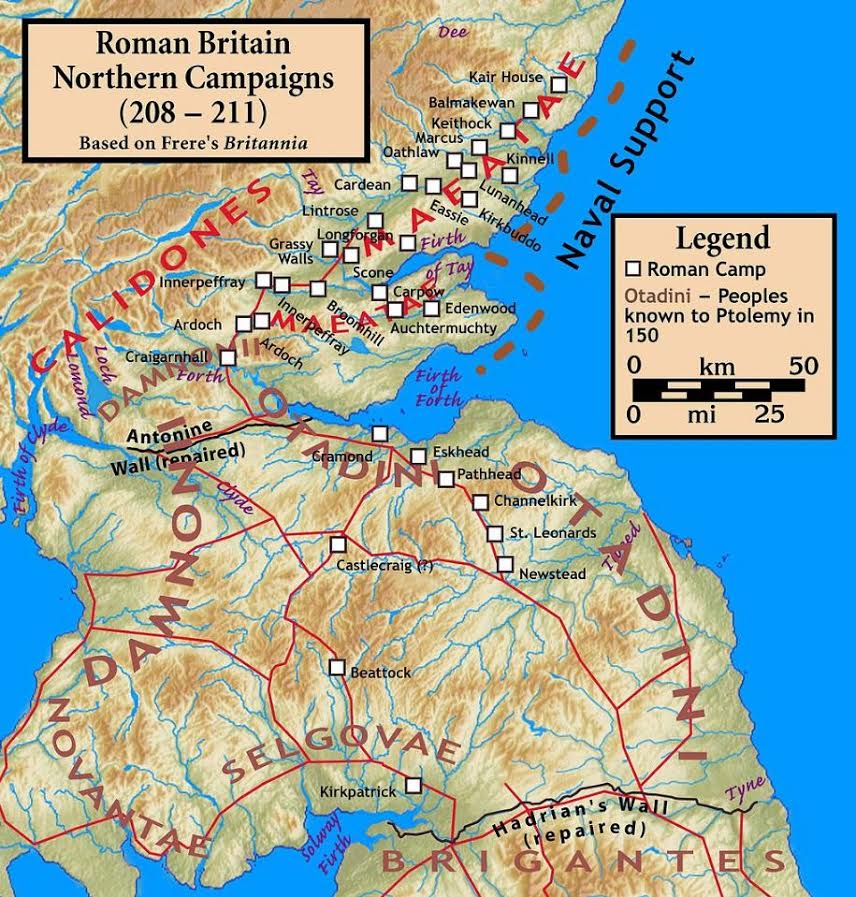

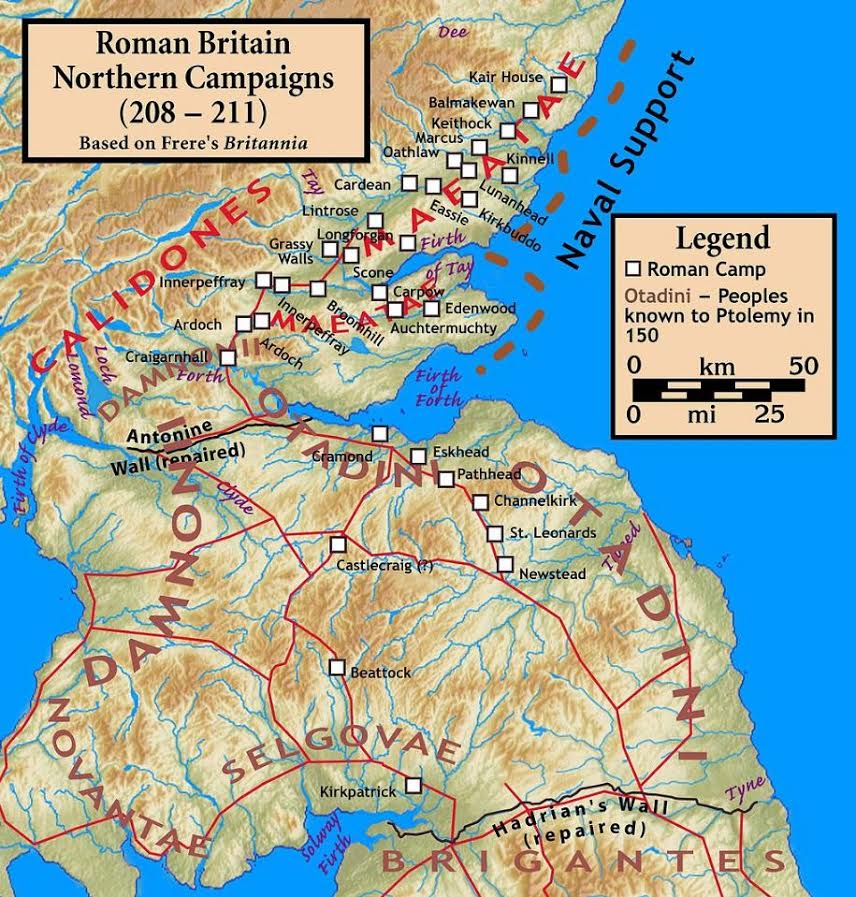

Warriors of Epona is set against the backdrop of the Severan invasion of Caledonia (modern Scotland). It was a massive campaign, and Rome’s last major attempt at subduing the tribes north of the Antonine Wall.

However, this was not the first time Rome had attempted to invade Caledonia. In fact, Septimius Severus’ legions were using the infrastructure of previous campaigns into this wild, northern frontier.

In this fifth and final part of The World of Warriors of Epona, we’re going to look briefly at the Roman actions in Caledonia prior to and including the campaigns of Emperor Septimius Severus.

The full scale conquest of Britannia was undertaken in A.D. 43 under Emperor Claudius, with General Aulus Plautius leading the legions. Campaigns against the British tribes continued under Claudius’ successor, Nero in A.D. 68.

The conquest of the South of Britain involved overcoming the tribes, including Boudicca and the Iceni, the Catuvellauni, the Durotriges, the Brigantes, and others, and the attempted extermination of the Druids on the Isle of Anglesey.

Boudicca

Eventually, after much blood and slaughter, the South was subdued, and the Pax Romana began to take root in that part of Britannia. (It pains me to gloss over so large a part of the history of Roman Britain, but we’re talking about Caledonia here…)

It was not until A.D. 71 that Rome decided it was time to invade Caledonia, and the man assigned this task was Quintus Petillius Cerialis, a veteran of the Boudiccan Revolt, and governor of Britannia at that time.

Once Cerialis’ legions were able to break through the Brigantes, it was time to press north into Caledonia.

The person who is most associated with these initial campaigns in Caledonia is none other than Gnaeus Julius Agricola, who had served in the campaigns against Boudicca in the South and who was also governor of Britannia from A.D. 77-85.

Agricola – Statue at Roman Baths, Bath, England

In around A.D. 80, Emperor Titus (A.D.79-81) ordered Governor Agricola to begin the campaigns into Caledonia by consolidating all of the lands south of the Forth-Clyde (roughly between Edinburgh and Glasgow). This involved taking on the tribes of the Borders, including the Selgovae, Maeatae, Novantae, and Damnonii.

It is in during this campaign that the fort at Trimontium, and many others were established in the Borders.

Commemorative stone at Newstead, in the Scottish Borders

By A.D. 81, Emperor Domitian had decided to order Agricola and his legions into Caledonia, and within two years, Agricola is said to have brought the Caledonians to their knees at the Battle of Mons Graupius.

He [Agricola] sent his fleet ahead to plunder at various points and thus spread uncertainty and terror, and, with an army marching light, which he had reinforced with the bravest of the Britons and those whose loyalty had been proved during a long peace, reached the Graupian Mountain, which he found occupied by the enemy. The Britons were, in fact, undaunted by the loss of the previous battle, and welcomed the choice between revenge and enslavement. They had realized at last that common action was needed to meet the common danger, and had sent round embassies and drawn up treaties to rally the full force of all their states. (Tacitus, Agricola; XXIX)

The Roman historian, Tacitus, was actually Agricola’s son-in-law, and his account, De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae, provides us with the best first-hand account of Agricola and his invasion of Caledonia.

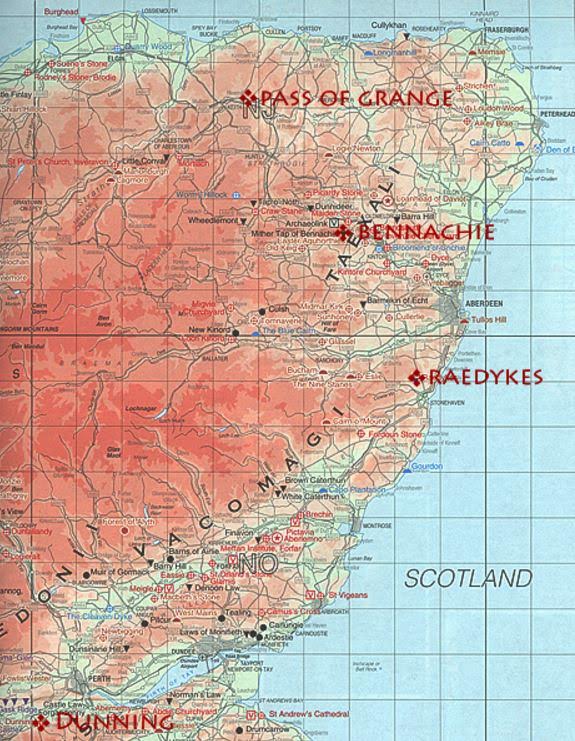

Possible locations for Battle of Mons Graupius

This is a time of legions exploring the unknown reaches of the Empire.

Sadly, the battlefield for Mons Graupius has not been identified, though there are certain candidates.

What is fortunate, however, is that Agricola’s legions left a long train of breadcrumbs in the form of marching camps, legionary bases, watch towers and of course, roads, all the way to northern Scotland.

And it is network of war that was to be used in later invasions of Caledonia.

Early Roman campaigns in Caledonia

War broke out again on the Danube frontier at this time, and so Roman man-power was sucked out of Britannia and Caledonia to meet threats elsewhere in the Empire.

And so, the legions in Caledonia went into a period of retrenchment and pulled back to the Forth-Clyde by A.D. 87.

By the time of Emperor Trajan’s reign, c. A.D. 99, Rome had retreated farther to the South to the Tyne-Solway, the future line of Hadrian’s Wall, construction of which began in A.D. 122.

The Caledonian lands for which Agricola and his legions had fought, had been given up for the time being.

Hadrian’s Wall

As was the case for centuries to come, the lands between the Forth-Clyde line, and the Tyne-Solway line, the area known today as the Scottish Borders, went into a period of push and pull, of occupation, retreat, and re-occupation.

It was during the reign of Antoninus Pius (A.D. 138-161) that it was deemed necessary to re-occupy the lands lost during the Flavian period, and so the army advanced again across the borders, using those same roads and forts that had been constructed by Agricola, and constructing new ones.

Twenty years after construction began on Hadrian’s Wall, Antoninus Pius ordered the construction of a new wall in Caledonia itelf in A.D. 142. This was the Antonine Wall, and it’s earth and timber ramparts ran the width of Caledonia from the Forth to the Clyde in an attempt to hem the raucous tribes in on their highlands.

The Antonine Wall

But, after more campaigning and entrenchment by Rome, the Antonine Wall was abandoned during the reign of Marcus Aurelius in around A.D. 163.

A few outposts remained in use to the north of Hadrian’s Wall, but for the most part, the bones of the Empire were left to rot and be overwhelmed by the Caledonians and their allies.

For the next forty years, the northern tribes became a menace, breaking through the frontier defences twice, once during the reign of Commodus (c. A.D. 184) and then again during the early part of Septimius Severus’ reign in A.D. 197.

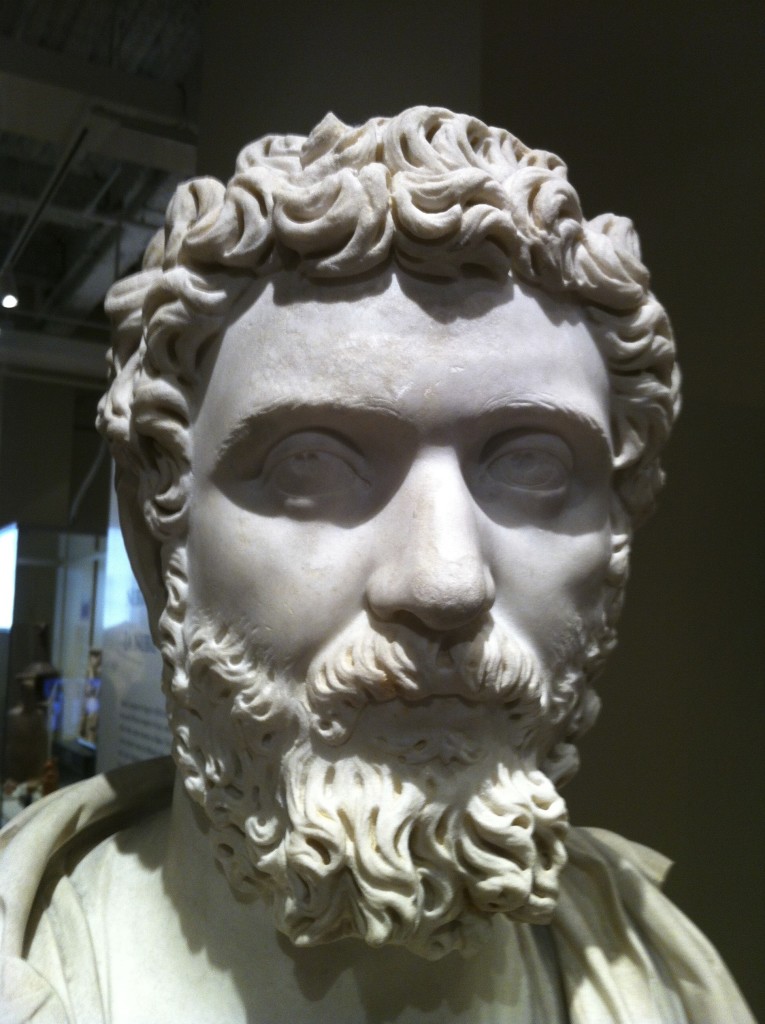

Septimius Severus

When Septimius Severus took the imperial throne, he was immediately engaged in consolidating the Empire after the civil war, and then taking on the Parthian Empire. He was a military emperor, and he knew how to keep his troops busy, and how to reward them.

The Caledonians had been a thorn in Rome’s side for a long while at that time, but it was not until A.D. 208 that Severus was finally able to deal with them. And so, the imperial army moved to northern Britannia, poised to take on the Caledonians once again.

We’ve already touched on Severus’ campaign in previous parts of this blog series. However, it’s important to note that this is believed to be the last real attempt by Rome to take a full army into the heart of barbarian territory.

Severus moved on the Caledonians with the greatest land force in the history of Roman Britain, making use of his predecessors’ fortifications (such as the Gask Ridge frontier) and roads, and penetrating almost as far as Agricola’s legions over a hundred years before.

According to Cassius Dio, when the inhabitants of the island revolted a second time, Severus:

…summoned the soldiers and ordered them to invade the rebels’ country, killing everybody they met; and he quoted these words: ‘Let no one escape sheer destruction, No one our hands, not even the babe in the womb of the mother, If it be male; let it nevertheless not escape sheer destruction.

Rome was poised for a final push, and ultimate victory over the Caledonians.

Goddess Fortuna

But Fortuna was not on Severus’ side, for it was at that time that his chronic health problems finally got the better of him.

In A.D. 211, the man who had won a brutal civil war, and who had finally brought the Parthians to heel, died at Eburacum (modern York) in Britannia.

Roman Tower at Eburacum (York)

His son, Caracalla, who was ill-equipped to handle the situation, struck a deal with the Caledonians, abandoning all the headway his father had made in that northern land, and all of the blood shed by fifty-thousand Romans in the Severan campaign.

What happened after the death of Severus is for another story (i.e. for the next book!). However the Severan conquests in Caledonia did usher in a fleeting period of tranquility.

Later expeditions into the North were mounted in c. A.D. 296 by Constantius Chlorus, and by his son, the future Emperor Constantine, in A.D. 306. However, neither of these campaigns were on a scale comparable to the Severan campaign.

Like other remote corners of the Empire, Caledonia must have seemed like a lost cause.

Roman Cavalry

But the Eagles and Dragons series is not yet finished with this exciting period of history in Roman Britain. Like Severus, we are poised for a final punitive push into the Highlands.

It’s a fascinating period in Roman history, and I hope you have enjoyed this journey through The World of Warriors of Epona with me. If you missed any of the previous blog posts in this series, you can read them all on one page by CLICKING HERE.

If you would like to learn a bit more about the Romans in Scotland, I highly recommend checking out the documentary Scotland: Rome’s Final Frontier with Dr. Fraser Hunter.

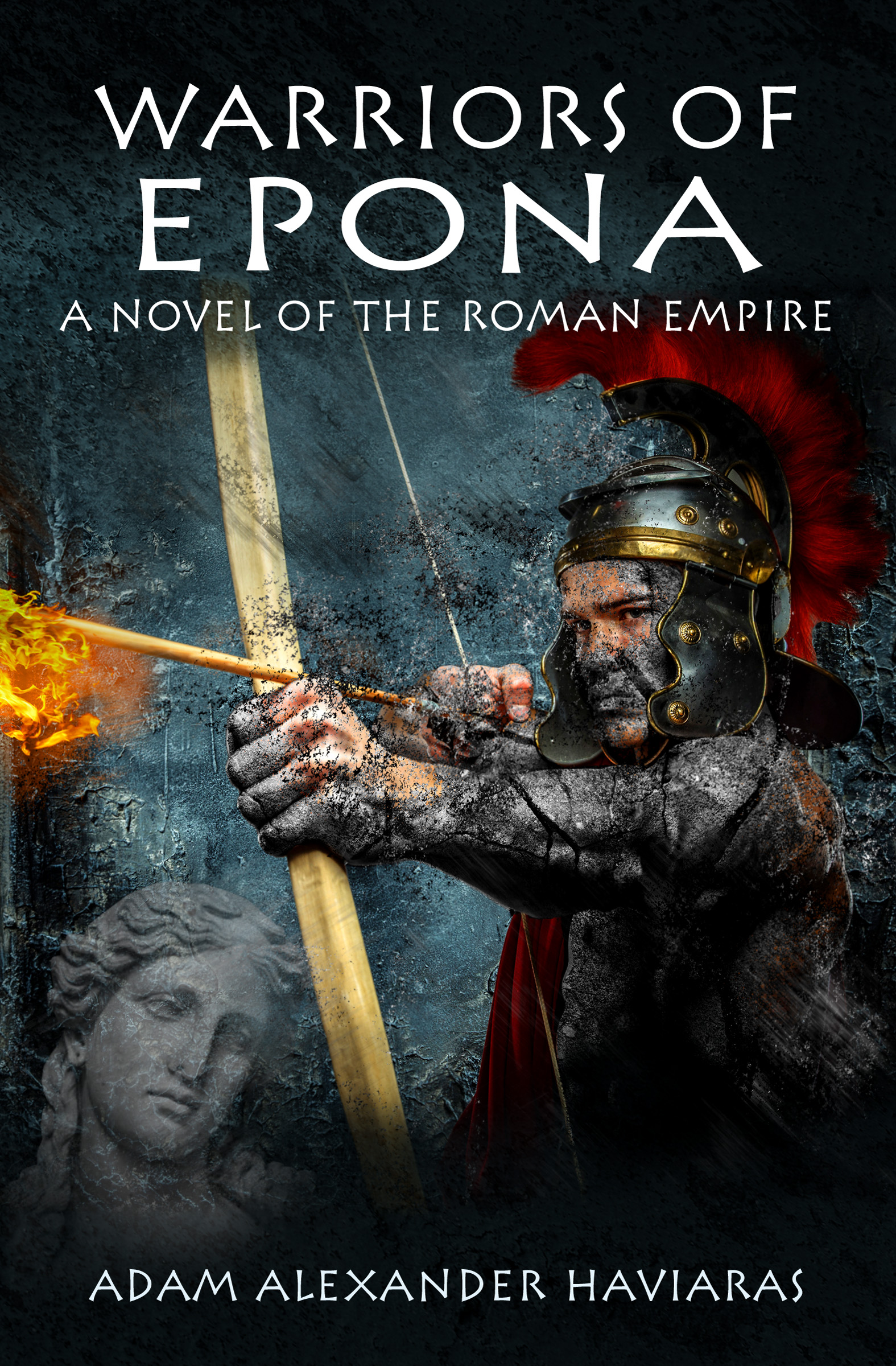

Warriors of Epona is out now on Amazon, Apple iBooks/iTunes, and Kobo, so be sure to get your copy today.

Remember, if you haven’t yet read any of the Eagles and Dragons novels, and if you want to get stuck in, you can start with the #1 Best Selling prequel novel, A Dragon among the Eagles. It’s a FREE DOWNLOAD on Amazon, Apple iTunes/iBooks, and Kobo.

Thank you for reading!

The World of Warriors of Epona – Part IV – Battle Line: The Gask Ridge Frontier

When most think of the Romans in Britannia or Caledonia, almost always the first thing that comes to mind is Hadrian’s Wall.

But there is another frontier that many people may not know of. You may have heard of some of the forts or camps that make up a part of this frontier, such as the legionary base at Inchtuthil.

Roman re-enactor watching the frontier

I’m talking about a line of forts and camps known as the ‘Gask Ridge’.

Research on this particular frontier has been less in depth than either the Antonine or Hadrianic walls. However, over the past ten years or so, the Gask Ridge has received its due attention thanks to the efforts of Birgitta Hoffmann and David Woolliscroft who have spearheaded the Roman Gask Project.

The importance of this frontier cannot be over-emphasized.

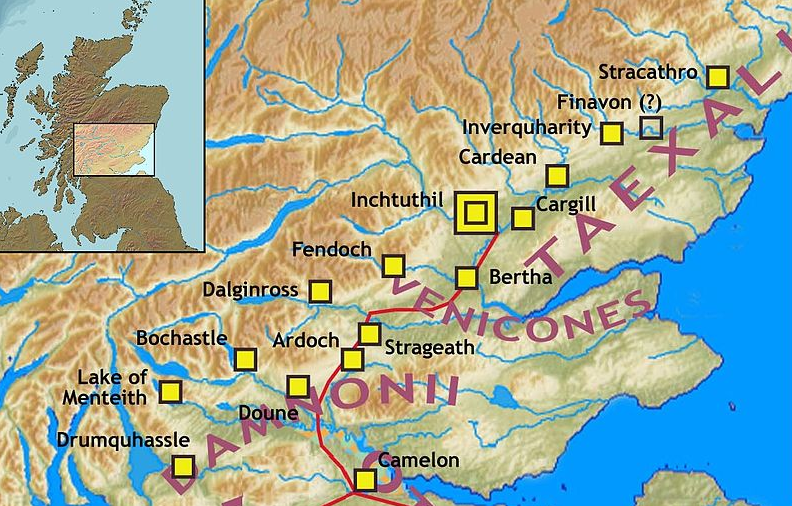

Gask Ridge Forts (Wikimedia Commons)

The Gask Ridge frontier has seen action in every one of Rome’s Caledonian campaigns and some of the research even shows that it was the first chain of forts in northern Britain, predating the other walls.

Some believe it is the first such frontier in the Empire!

It consists of a long line of forts, watchtowers, and temporary marching camps that run from the area of Stirling, on the Antonine Wall, past Doune, along the edge of Fife and up into Angus, all the way to Stracathro.

This is a very impressive line of defence built by Rome with the intent of holding the Caledonii at bay, and separating the highlands from the flatter plains leading to the North Sea.

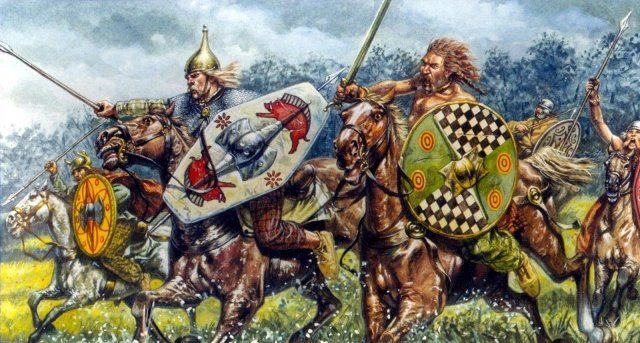

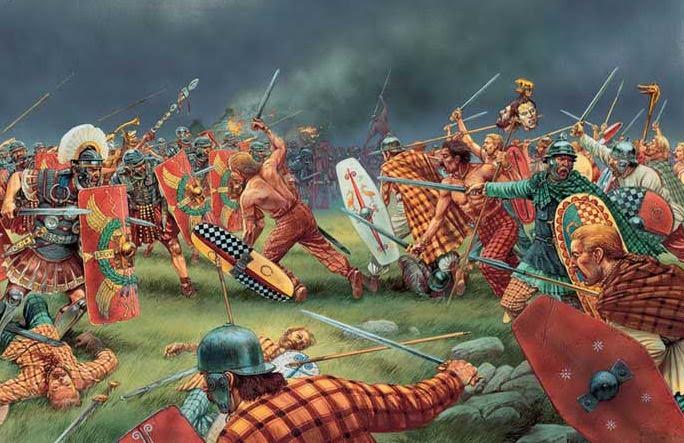

Artist Impression of Caledonian Warriors

In writing Warriors of Epona, the trick was finding out which forts may have been in use during the campaigns of Septimius Severus in the early 3rd century A.D.

The forts of the Gask Ridge were used mostly during Agricola’s campaign in the late first century, and then by Antoninus in the mid-second century.

Roman road along Gask Ridge in Perth and Kinross

The Romans definitely knew how to pick a strategic location along the perfect line of march, so it’s likely marching camps would have been reused in later campaigns. But some of that is supposition.

One site that we know was built as part of the Severan campaign was the legionary fort at Carpow, on the banks of the Tay. With a large part of a legion stationed there, the supply chain could be maintained by sea with Roman galleys coming up the Tay. It was also at this time that some believe the first Tay Bridge was built when Severus ordered the creation of a boat or pontoon bridge to the Angus side of the river.

Aerial view of Horea Classis site (Carpow)

Carpow was a large base of operations intended to make a statement – Rome was going to stay this time! Severus was a military emperor who liked to prove his point. He was in Caledonia to finish what other Roman emperors had started, just as he did in Parthia.

The Gask Ridge plays a key role in Warriors of Epona, especially the forts that may have seen re-use during the third century, among them the forts at Camelon, Ardoch, Fendoch, and Bertha, the latter being where Lucius Metellus Anguis establishes his forward base.

Ardoch Roman camp remains

Of course, one of the exciting things about writing historical fiction, after the research, is filling in the gaps and exploring possibilities.

Because research on the Gask Ridge is relatively new, we can certainly look forward to learning more from Hoffmann, Woolliscroft, and everyone else on the Roman Gask Project team who are leading the charge to further our knowledge of this ancient frontier.

One thing that I have discovered over the years is that even though the history and research are very important, at the end of the day, in fiction, the story must come first.

With Warriors of Epona, history and story have come together nicely, and that has been pure magic!

Cheers, and stay tuned for the fifth and final part of The World of Warriors of Epona.

Aerial view of Fendoch and the Sma’ Glen from the south with the fort on the low plateau in the right foreground.

If you are interested in reading more about the Roman Gask Frontier, or about the Romans in Scotland, do have a look at the following resources:

The Roman Gask Project: http://www.theromangaskproject.org/

Rome’s First Frontier: The Flavian Occupation of Northern Scotland. By D. J. Woolliscroft and B. Hoffman. Pp. 254. ISBN: 0 7524 3044 0. Stroud: Tempus. 2006.

Warriors of Epona – Eagles and Dragons Book III is one sale now!

But remember! If you have not yet read any of the Eagles and Dragons novels, and if you want to start off on an adventure in the Roman Empire, you can pick up the #1 Best Selling prequel novel, A Dragon among the Eagles. It is a FREE DOWNLOAD on Amazon, Apple iTunes/iBooks, and Kobo.

The World of Warriors of Epona – Part III – Combatants: The Tribes of the North

In the last post we looked at one of the sites that was right in the middle of the war zone beyond Hadrian’s Wall, a place that Rome used to good effect as it marched north over Britannia.

But who were the tribes north of Hadrian’s Wall that caused Rome such misery and bloodshed for over a hundred years? Who was Rome fighting?

In Part III of The World of Warriors of Epona, we’re going to look at the various combatants in our story.

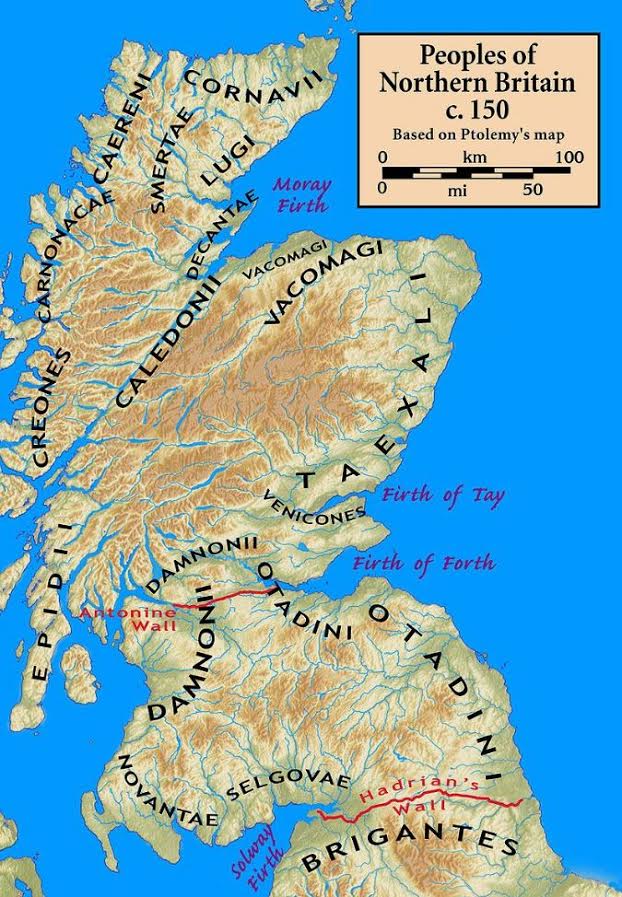

Tribes of Northern Britain according to Ptolemy (Wikimedia Commons)

On a couple of occasions in the second century, the tribes north of the wall rebelled against Rome, and by the time Septimius Severus had finally defeated the Parthian Empire in the East, the time had come for Rome to deal once-and-for-all with the tribes of Caledonia.

This was no small venture.

Severus marched into Caledonia with at least six legions, his Praetorian Guard, plus numerous auxiliary units and cavalry ala, to deal with the rebellious tribes.

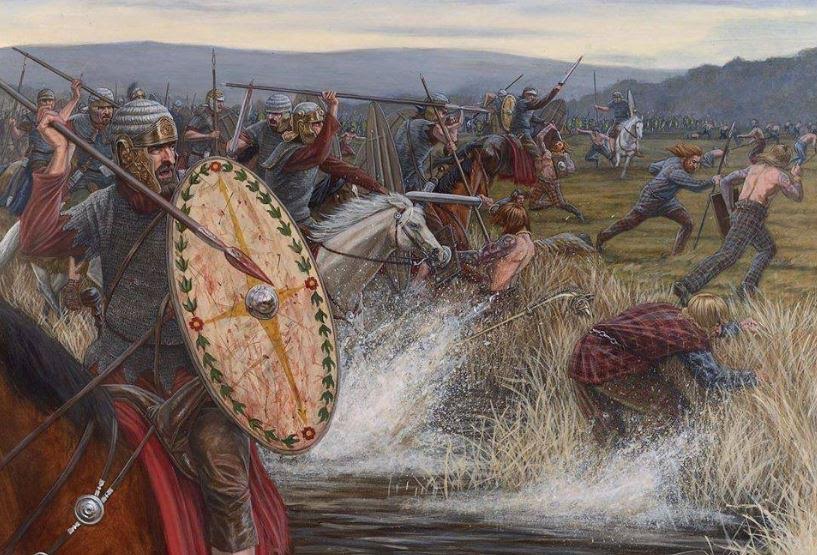

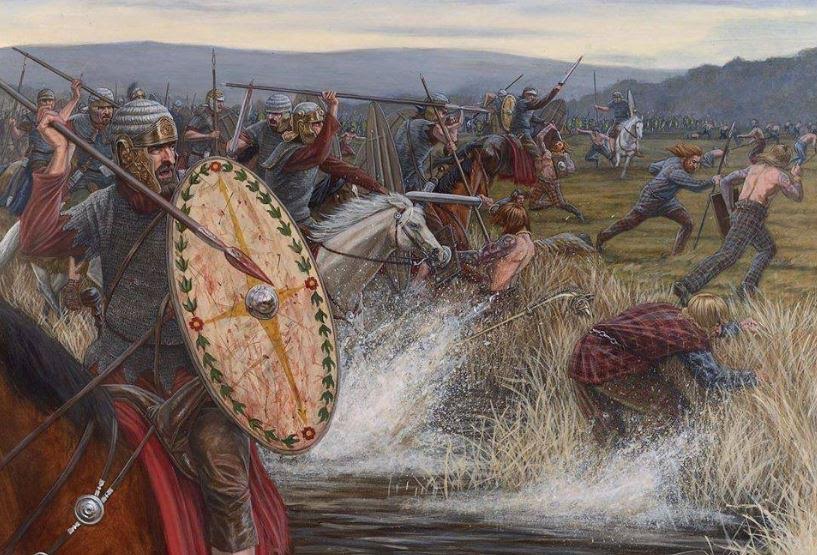

In this major offensive, the legions had to deal with bad weather, rough terrain, mountains, bogs, and river fords, as they attempted to take back strategic positions Rome had once held in previous campaigns.

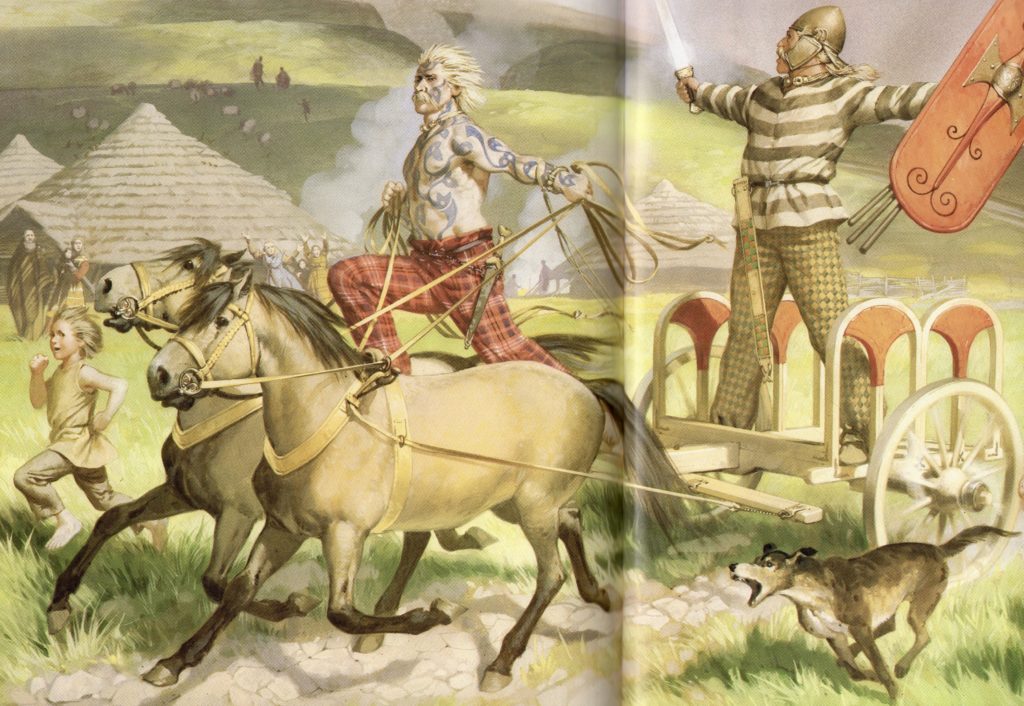

Rome’s foes were also cunning and highly skilled at their unique guerilla tactics, never meeting the legions in open, pitched battle. They were mostly infantry, but they also used war chariots. Their weapons often consisted of small round shields, short spears, and swords.

Their devices lured many a legionary to his doom too. Livestock would be used as bait to lure Roman troops into swamps or ambushes, and warriors would lie in wait submersed beneath the surface of water when the Romans were marching by.

It was all about hit and run and hacking away at the edges of Rome’s forces. And they were so good at it that, by the end of the campaign, the Romans are said to have lost around 50,000 men.

So who were these expert guerilla fighters who proved such a thorn in the side of Rome for almost the entirety of its time in Britannia and Caledonia?

Let’s find out.

Most of what we know about the names of the tribes at this time in Caledonia and northern Britannia comes down to us from Claudius Ptolemaeus, or Ptolemy as most know him.

Ptolemy was a Greco-Egyptian mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, and geographer who lived c. A.D.100-170. It is his work, known as Geographia, which compiles geographical coordinates and knowledge of the Roman Empire in the second century, and which mentions many of the tribes and locations we are dealing with during the Severan invasion of Caledonia.

Severan Campaigns in Caledonia (Wikimedia Commons)

Other sources for places during this period and in this region are the Ravenna Cosmography, which is an early eighth century list of place-names from Ireland to India, and the second century Antonine Itinerary. The latter was created under Antoninus Pius and likely finalized under Caracalla at the beginning of the third century. The portion of the itinerary known as Iter Britanniarum was a list of Roman place names and roads in Britain.

Rome was anything but invincible in this fight, so we need to look first at those who fought alongside the legions in Caledonia.

One of Rome’s allies in this fight were the Votadini, and they play a large role in Warriors of Epona.

This tribe of Celtic Britons held the territory of what is now south-east Scotland and north-east England, and they had been Roman allies for generations by the time of the Severan invasion, and may well have been one of the key Romano-British fighting forces.

The Votadini came under Roman alliance in the mid-second century, and proved to be a great stabilizing entity between the Antonine and Hadrianic walls, mainly the region we know today as the Scottish Borders.

Dunpedyrlaw (Trapain Law) – Capital of the Votadini

Their capital, named ‘Curia’ by Ptolemy, was called Dunpendyrlaw, which meant the ‘fort of the spear shafts’. Today, the massive hill fort at this place is known as Traprain Law. This place was occupied by the Votadini and their descendants until about A.D. 400 when the capital was moved to Din Eidyn, that is, Castle Rock in Edinburgh.

One of the most magnificent finds from the Votadini capital of Dunpendyrlaw is a hoard of Roman silver plates, cups and more. Some believe this was given to the Votadini in thanks for service to Rome, others that it was a bribe to keep them in check and fulfilling their role as allies.

Trapain Law Treasure

The Votadini’s descendants were none other than the Gododdin, those Britons who made an heroic last stand at the battle of Catraeth around A.D. 600 when the Saxons were poised to overrun the island. This final battle is chronicled in the poem, Y Gododdin by Aneirin.

The poem was certainly an inspiration for me when I was writing about the Votadini in this book. It seems quite romantic in a sense, the Votadini, loyal Rome, standing against the enemy tribes after Rome pulled back from Antonine Wall.

Artist impression of Roman cavalry ala engaging Caledonians

The other allies in this fight with Rome, although perhaps a little more reluctant, was a tribe known as the Venicones. Their lands covered what is basically modern Fife, in eastern Scotland, and where, funnily enough, my alma mater, St. Andrews University, is located.

The Venicones are known to us from Ptolemy who mentions a town by the name of ‘Orrea’ which many have come to identify as the Roman settlement of Horea Classis. This is believed to be the site of the Severan legionary base at Carpow, along the Tay estuary, and it is from here that the emperor likely oversaw the Caledonian campaign, when not in the northern capital of Eburacum (York).

The Venicones were in a tough position. On the one hand, they were neighbours with Rome’s enemies, the Caledonii to the West, and the Taexali to the North.

Crop marks showing outline of Roman Principia at Carpow

They chose to side with Rome in the fight, but one wonders how much of a choice that was? As it turned out, the legionary base and ports at Horea Classis (Carpow) and the forts of the Gask Ridge frontier (the topic of our next post), were all in the lands of the Venicones.

What must the Venicones have been thinking when they agreed, or were forced, to become a Roman client state?

I wouldn’t have wanted to be the one throwing those dice!

Ordnance Survey map extract (Gask ridge and Venicones lands)

Now we come to Rome’s adversaries in the Caledonian campaign.

Even though we have some hints from Ptolemy and the other sources, it is difficult to be exact in naming the tribes that Rome was fighting on this far northern frontier. Many Roman writers, including Cassius Dio, use the name ‘Caledonians’ for all the tribes rebelling against the Empire.

In writing Warriors of Epona, I had to pick and choose which tribes I would write about, and which to leave out.

There are three peoples in particular who may well have joined forces with larger groups but which I decided to leave out of the story specifically.

The first are the Novantae. These were a people of the second century who lived in modern Galloway and Carrick in south-western Scotland. The Saxon historian, Bede, refers to the Novantae as Picts in his history, but it is believed that they were a Brythonic people.

Another group I decided to leave out of the story were the Damnonii. These were Celtic Britons located in Strathclyde in southern Scotland. They are only mentioned by Ptolemy and there really is not enough information on them and their activities.

The third group I decided to leave out was the Maeatae. This group was larger, and believed by some to be a union of smaller tribes whose lands lay somewhere along the Antonine Wall, westward from Stirling. The little that I read about them indicates that they likely joined forces with the Caledonii in the rebellion of A.D. 210.

British warriors (illustrated by Angus McBride)

In Warriors of Epona, the Romans have to deal with two main adversaries in the Caledonian campaign – the Selgovae, and the Caledonii.

At the beginning of the book, Lucius Metellus Anguis and his Sarmatian cavalry ala are engaging the Selgovae in the lands around Trimontium, north of the wall.

The fighting has been brutal and the leader of the Selgovae ruthless in his campaign against Rome.

Who were the Selgovae?

They were a large tribe of Britons mentioned by Ptolemy in the late second century. Their territory covered south-west Scotland and what is Dumfriesshire today.

It is believed that they were related to the Brigantes, Rome’s old enemies south of Hadrian’s Wall.

The Selgovae, like many other British tribes, used chariots in warfare. They also lived in stone huts and had many hill forts across their lands. Their warlike demeanour and the strength of their fortresses made them an obvious target for Rome during successive campaigns. Like the Brigantes, the Selgovae were more troublesome than other tribes.

Aerial view of Eildon Hill North – Capital of the Selgovae

In a previous post, we have already discussed the legionary fortress at Trimontium, the place Lucius uses as a base in his fight against the Selgovae. But before Rome occupied the site, Eildon Hill North, one of Trimontium’s three peaks, was the main tribal centre of the Selgovae.

Writing about this group of warriors, making a last stand against Rome at the beginning of the story, was thrilling and bitter-sweet. They were a once-proud people, but, like many who stood against Rome, they had to face the harsh realities of the Empire.

The main opponents of Rome during the Caledonian campaigns of Septimius Severus, and in Warriors of Epona, were the Caledonii.

These were the indigenous people of what is now Scotland.

They were originally considered to be another group of Britons, but now it is more widely believed that they were the people who later came to be known as the Picts.

Pictish stone at the Meigle Museum in Strathmore, Scotland

The Caledonii may also have been a federation of many tribes in Scotland, as well as remnant forces fleeing north after being defeated by Rome in the South.

One thing is certain – Rome was a definite threat to all the northern tribes, and the scene was set for a brutal fight, with the Caledonii leading the charge.

The Caledonii were certainly a hearty people who lived in a very rugged world that included the Scottish Highlands. As the first century historian, Tacitus, points out, they had red hair and long limbs. Much later than Tacitus, Cassius Dio, our main source for the period, added a bit more colour to the picture of the Caledonii, saying that they:

…inhabit wild and waterless mountains and desolate and swampy plains, and possess neither walls, cities, nor tilled fields, but live on their flocks, wild game, and certain fruits; for they do not touch the fish which are there found in immense and inexhaustible quantities. They dwell in tents, naked and unshod, possess their women in common, and in common rear all the offspring. Their form of rule is democratic for the most part, and they are very fond of plundering; consequently they choose their boldest men as rulers. The go into battle in chariots, and have small, swift horses; there are also foot-soldiers, very swift running and very firm in standing their ground. For arms they have a shield and a short spear, with a bronze apple attached to the end of the spear-shaft, so that when it is shaken it may clash and terrify the enemy; and they also have daggers. They can endure hunger and cold and any kind of hardship; for they plunge into the swamps and exist there for many days with only their heads above water, and in the forests they support themselves upon bark and root…

(Cassius Dio, Roman History 12,1)

One must always take ancient writers’ descriptions with a grain of salt, of course, but if even a part of this description of the Caledonii is true, then the Romans must have felt like they were fighting ghosts as they marched into Caledonia.

Artist impression of a Caledonian warrior

The Severan campaign was certainly not the first time Rome engaged the Caledonians. There were other campaigns which we shall look at in a later post in this blog series.

Prior to Severus’ invasion, the Caledonians rebelled in A.D. 180 when they travelled south and breached Hadrian’s Wall. And then in A.D. 197, the Caledonii, Brigantes, and Maeatae led another attack on the frontier.

At the time of these rebellions, Severus was campaigning against the Parthians in the East.

By the time A.D. 209 rolled around, Rome’s legions were set for the biggest offensive yet into Caledonia.

Once again, Cassius Dio gives us an account:

Severus, accordingly, desiring to subjugate the whole of it, invaded Caledonia. But as he advanced through the country he experienced countless hardships in cutting down forests, levelling the heights, filling up swamps, and bridging rivers; but he fought no battle and beheld no enemy in battle array. The enemy purposely put sheep and cattle in front of the soldiers for them to seize in order that they might be lured on still further until they were worn out; for in fact the water caused great suffering to the Romans, and when they became scattered, they would be attacked. Then, unable to walk, they would be slain by their own men, in order to avoid capture, so that a full fifty thousand died.

(Cassius Dio, Roman History 14,1)

Caledonia: The Scottish Highlands