Hello History-Lovers!

This week on the blog we’ve got a special post about some amazing women from ancient and medieval history.

As has often been the case in history books and classes, the focus of historical personages has been male-oriented. Men declared most wars, made political decisions, ruled, and basically determined the future for numerous societies, kingdoms and empires.

While there have been some amazing men in history, there have also been many incredible women who have displayed great strength, resilience, and courage on the world scene, women who have set a shining example and challenged the status quo.

Over my years of study, I can’t remember how many times I’ve come across a woman from history who blew my mind with their daring, but whose life was rarely explored in-depth in any of my courses or the books I read. With hope, curricula in high school and beyond have changed to more properly reflect the role of women in history.

There are far too many outstanding women in history for me to list them here, but with this post I wanted to introduce you to a small group of women who have left a great impression upon me, personally, during my years of study, research and writing. The biographies below will be brief, but I hope they encourage you to read more.

Kyniska of Sparta

396 B.C.

Those of you who have read Heart of Fire will be familiar with Kyniska of Sparta, one of the main protagonists of the story. The very first time I read about this Spartan princess, I knew immediately that I had to write a story around her achievements.

Kyniska of Sparta was the daughter of King Archidamus II (476-427 B.C.), the Eurypontid King of Sparta. She was also the half-sister of King Agis, and sister to King Agesilaus II (444-360 B.C.) who waged war on both the Persians and his fellow Greeks.

It is believed that Kyniska was born sometime around 440 B.C. in Sparta and, unlike other Greek women beyond Sparta, she grew up training herself physically and mentally, as was expected of strong, Spartan women.

What makes her so special?

Well, in addition to winning in the foot race at the Heraian Games that took place at Olympia, she was also the first woman in history to win at the Olympic Games when she entered her team in the four horse chariot event. And not only did she win, she did it at two Olympiads in 396 B.C. and 392 B.C.!

When I first wrote about Kyniska, some people, including women, told me that her achievements didn’t mean much since she did not drive the chariot herself. However, my answer to that is that that is a modern perspective only. We have to keep in mind that in the world Kyniska inhabited, women were considered to be very little, other than chattel. They had no say, no involvement in affairs of war or state, and certainly no place in the Olympic Games, not even being permitted within the sacred sanctuary of the Altis, unless they were a priestess.

For someone like Kyniska to raise and train her horses – which she did – and then to enter the Olympics to compete against the richest and most powerful men of the city-states of the Greek world took no little amount of courage.

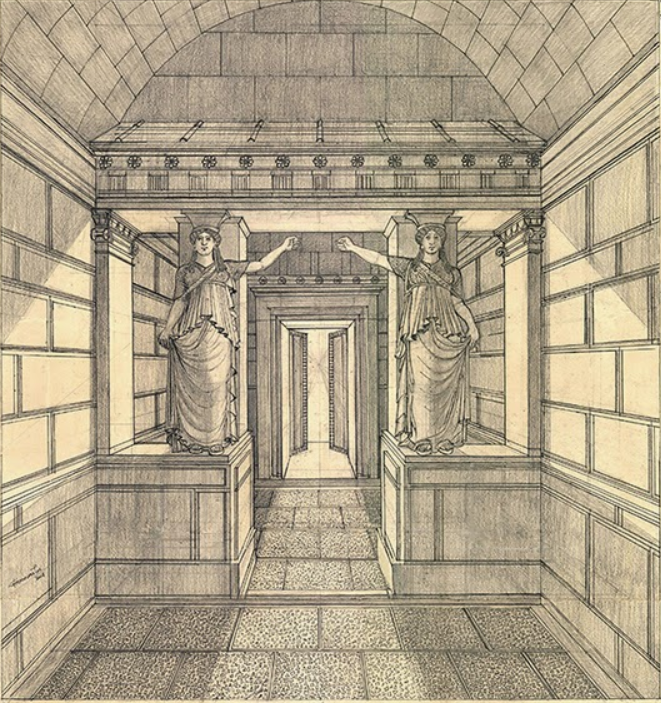

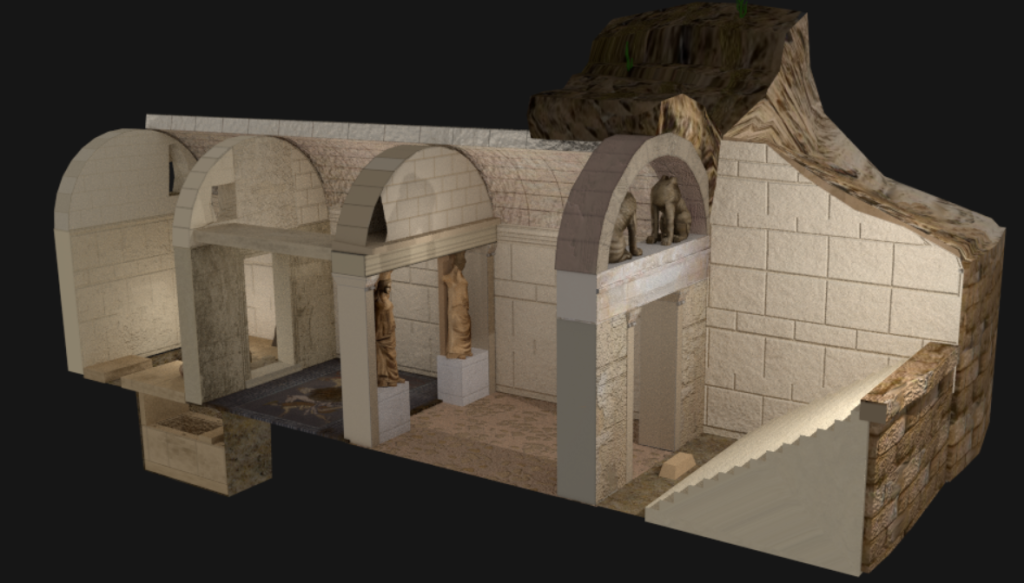

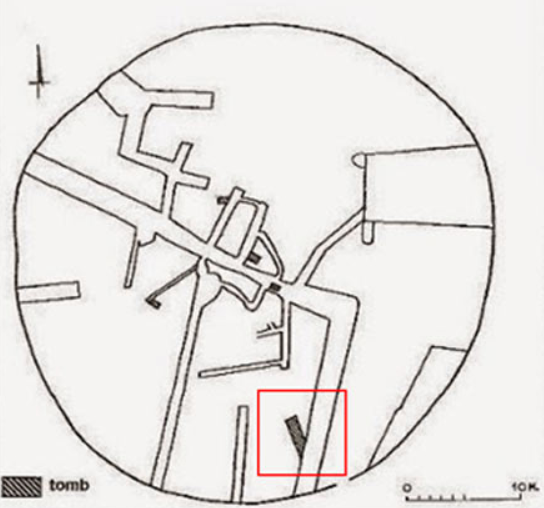

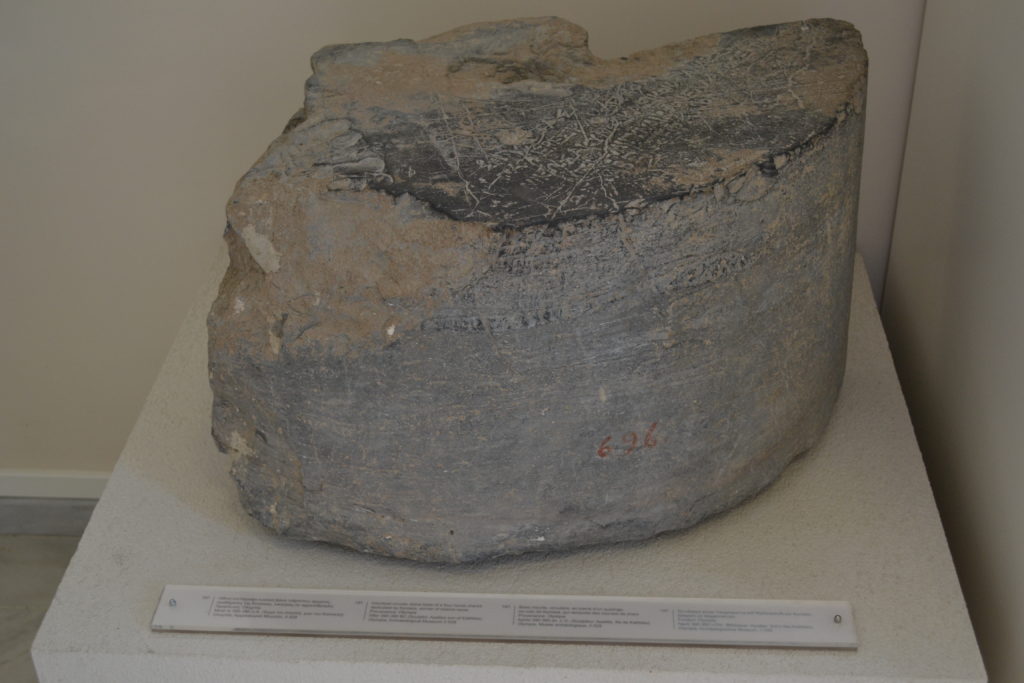

Inscribed base for the victory statue commemorating Kyniska’s victory at the Olympic Games. It is now located in a small room at the Museum of the Olympic Games in ancient Olympia, Greece. It was amazing to see this piece of stone that represented such an earth-shattering change in Olympic history!

Kyniska’s actions show that she was a strong, willful and outspoken woman in the highly misogynistic world of ancient Greece, and of Sparta.

She also opened the doors to other women to compete in the Olympic Games, includingEuryleonis, in 368 B.C., who also makes an appearance in the story of Heart of Fire. Women from other city-states, including Belistiche, Zeuxo, Encrateia, Hermione, Timareta, Theodota of Elis, and Cassia, also eventually competed and won.

For me, Kyniska is a hero of ancient history!

If you would like to read more about Kyniska of Sparta, you can CLICK HERE for the full blog post on her. You can also read about her in Heart of Fire: A Novel of the Ancient Olympics which features her achievement at the Olympiad of 396 B.C.

Olympias

375 – 316 B.C.

One name that conjures images of motherly pride, female strength, and perhaps illustrates the words ‘hell a fury like a woman scorned’ better than any other is that of Olympias, the wife of King Philip II of Macedon, and the mother of none other than Alexander III (the Great).

One thing that many great women in history seem to have in common is that they have been demonized by history, and male historians, to an extent. Olympias is certainly no exception.

As the daughter of Neoptolemus I of Epirus, King of the Molossians, Olympias was descended (and she fervently believed it!) from the Greek hero, Achilles.

She was a strong, passionate and imperious woman in the male-dominated world of ancient Greece. She was also a dedicated worshipper of Dionysus, there being many tales of her ecstatic, mad dances in honour of the god.

In 357 B.C., she married Philip of Macedon and quickly proved to be no typical wife of ancient Greece. She was not one to be locked away, or to remain silent. She and Philip were often at odds, and when he took another wife, she returned to her home in Epirus. Philip was murdered of course, and some say that she had a hand in that so as to secure the position of her son, Alexander, upon the throne.

It was also said that Olympias also murdered that wife of Philip’s, as well as the son she more.

One thing is for sure – you would not want to get in the way of this Greek mother and her son.

While Alexander was conquering lands all the way to India, Olympias fought to protect his back, and was often at odds with Alexander’s regent, Antipater, whom Olympias did not trust to look out for Alexander’s interests.

Not welcome in Macedon during Alexander’s absence, Olympias returned once more to Epirus to rule alongside her daughter, Cleopatra.

It would be difficult to call Olympias an expert at diplomacy, though she was a shrewd politician and seems to have had a knack for knowing who could or could not be trusted with her son’s interests.

Olympias was more of a force of nature, and after Alexander’s death, she returned to Macedon in 319 B.C. to support Polyperchon against Cassander, Antipater’s son, and one of Alexander’s generals.

Despite her grief over the death of her beloved son – a son some believed was actually the son of Zeus – her goal was to secure the inheritance of her grandson, Alexander IV. Olympias gave Roxana, Alexander’s wife, and her son her protection, and promptly went to war against Cassander. She won many battles in this war, a war she fought on behalf of her family.

But she was, apparently, too brutal.

When Cassander captured her at Pydna, she was put to death by the families of her victims over the years.

Here, it is important to note that Cassander’s soldiers refused to hurt her. They would not be the executioners of Alexander’s mother.

Whatever you might think of Olympias, there is no doubt that she was the ultimate woman of strength and determination, a woman who could well have lived up to her shared blood with Achilles himself.

If you are looking for a relatively accurate portrayal of Olympias, you might want to check out Oliver Stone’s epic film, Alexander, in which she is portrayed by Angelina Jolie. The historical advisor on the film was Robin Lane Fox, one of the definitive biographers of Alexander the Great. You can find Fox’s book HERE.

If you’re looking for novels, Valerio Massimo Manfredi’s Alexander Trilogy is a great read.

Cleopatra VII Philopator

69 – 30 B.C.

The name of Cleopatra needs no introduction. She is perhaps the most famous (and final) queen of ancient Egypt, portrayed in art, literature, and modern media countless times.

However, many portrayals of this last ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty have been extremely unfair and, frankly, insulting. One example is the HBO series Rome. As much as I loved that show, the portrayal of Cleopatra as a sort of nymphomaniac junkie could not have been further from the truth.

If that is the case, who was the real Cleopatra, other than a descendent of Alexander the Great’s general, Ptolemy, and a lover of Julius Caesar and Marcus Antonius?

She was royalty, and she was a survivor. She was also well-educated, a cunning diplomat, and a skilled naval commander. She was also highly intelligent, being fluent in several languages – she was the only Ptolemaic pharaoh fully fluent in the Egyptian language of her people!

Cleopatra was a brighter star than most of the rulers of her family dynasty. She was a champion of her people, and she sought to secure their future by any means necessary, going so far as to become the mistress of another rising star on the world stage, Julius Caesar, whom she bore a son named Caesarion.

When she and her son arrived in Rome in 46 B.C. their entrance became legend, but she was only to remain there until 44 B.C. when Caesar was murdered. After that, her son, and Egypt, were at the forefront of her thoughts, and she set about securing her position and that of her son by any means, including poisoning her younger brother.

Cleopatra finds herself in legend again with the subsequent romance between her and Marcus Antonius, and this affair has been written of, painted, and poeticized again and again. Sometimes the telling is quite romantic, but it is foolish to believe that the great women of history were only as great as their affairs, I think.

She became a mother yet again, this time giving Antonius three children – Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene, and Ptolemy Philadelphus. Though the accounts speak of love between Antonius and her, Cleopatra, during this time, negotiated the return of Egypts lost lands, and then obtained new lands, from Rome.

In the West, however, Cleopatra’s influence on Antonius and her imperial ambitions caused Octavian to begin a smear campaign against her that, to this day, taints our perception of her.

Things came to a head at the battle of Actium, in which Octavian’s forces defeated those of Cleopatra. The end was near. It should be said here that there is no evidence that she fled the battle when it appeared lost. That was perhaps another fabrication of Octavian’s propaganda machine.

When they returned to Egypt after the battle, Antonius, like a good Roman, committed suicide.

Seeing Octavian closing in, and refusing to be an ornament in his triumph in Rome, Cleopatra, the last ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty, committed suicide by snake bite on August 10th, 30 B.C. Her children by Antonius were spared and raised by his Roman wife, Octavia, but her son, Caesarion, was murdered.

Thus ended the Hellenistic Age that had begun with Alexander the Great.

Some people love Cleopatra, others hate her. But there is no denying that she was a passionate woman of extremes. She certainly owned her role as Egypt’s queen, and fought hard for herself, her people, her kingdom, and for those whom she loved.

In reaching so high, she was perhaps burned by the sun, but it is indeed hard to imagine anyone else capable of so much!

If you would like to read more about Cleopatra, you should definitely check out the biography, Cleopatra, by Michael Grant.

And as far as films, I still love the epic classic Cleopatra with Elizabeth Taylor.

Livia Drusilla

58 B.C. – A.D. 29

If were are talking about the strong women behind the men who ruled the world, we would be remiss if we did not include Livia Drusilla, later Livia Augusta, first empress of the Roman Empire.

Many of you might know of Livia from the BBC drama, I Claudius. She was not only a great power behind the imperial throne, and not a woman to be trifled with, she was also the matriarch of one of the most famous dynasties of ancient Rome.

I’ve always been curious about Livia and her world, amazed by the power she seemed to have wielded over the rulers of Rome. She was the wife of Emperor Augustus for fifty-two years, and as such she helped to build a new, Roman world.

She was also the mother of Emperor Tiberius, the grandmother of Emperor Claudius who deified her, the great-grandmother of Emperor Gaius (the infamous Caligula), and the great-great-grandmother of Emperor Nero.

If there is a supreme example of the Roman mater familias, Livia is it.

She met Octavian (future Augustus) in 38 B.C. and married him. By all accounts, she captured his heart, but she also gave him a great deal of strength.

Morals and traditions were important to the Romans, and Livia excelled at these, being a dutiful wife and mother in the eyes of the Roman people.

But she also helped Augustus with his dynastic plans. An Empire cannot be born without crises, and Livia helped her husband to weather them all.

She played a more prominent role in state and family affairs than any Roman woman before her.

Livia was extremely intelligent and perceptive, and she was Augustus’ most loyal, trusted advisor. In fact, it’s even possible that his reign would not have lasted so long without her. Together, they spearheaded what was thought to be a return to true Roman morality.

The ‘Grand Cameo of France’ artifact showing the Julio-Claudian Family, including Livia beside her enthroned son, Tiberius

However, there were rumours of her plotting to secure her son Tiberius’ accession to the throne by murdering several of Augustus’ possible heirs. Odd that once Tiberius came to the throne, the two were estranged.

Caligula, who lived with her for a time, is said to have called her a cunning intriguer, ‘Odysseus in a dress’!

To have survived for so long in the world of ancient Rome and all the dynastic family struggles that entailed, and to have been at the forefront of the creation of one of the world’s greatest empires, I think it can truly be said that Livia Drusilla was an exceptional woman deserving of her deification.

She also cleared the way for other strong women of Rome who followed in her footsteps.

For a wonderful portrayal of Livia in film, you should definitely watch the BBC mini series of I, Claudius, in which this titan of ancient Rome is expertly played by Sian Philips.

The Robert Graves book of I, Claudius, which the television series is based on, is a wonderful read too, and though it perhaps takes some poetic exaggeration, it is a fantastic book.

Boudicca – Queen of the Iceni

A.D. 60

When I think of strong women from the ancient world, Boudicca is at the forefront of my mind. I can see her now, tall, standing on her war chariot, her red hair blowing in the wind, and vengeance in her eyes.

Her acts are inspiring and heroic, and her story one of tragedy.

Boudicca was the wife of King Prasutagus of the Iceni nation of Celts, who ruled the area of modern day Norfolk. Prasutagus was a client king of Rome at the time, but upon his death, he left half of his possessions to Emperor Nero.

It did not take long for the Roman officials to descend on the Iceni to seize everything. More than that, they flogged Boudicca publicly and raped her two daughters.

Boudicca’s story is one of horror and war, and to me, her name is synonymous with rage and swift vengeance.

After these grievous attacks upon herself, her daughters, and her people, Boudicca rallied the Iceni nation, as well as the neighbouring Trinovantes (in modern Essex and Suffolk), and moved against the Romans.

With an army of one hundred-thousand, Boudicca sacked the cities of Camulodunum (Colchester), Londinium (London), and Verulamium (St. Albans), the most important towns in southern Britannia. Her forces killed seventy to eighty thousand Romans and Britons living in those towns, and they went on to trounce forces from the IX Hispana Legion.

But her time of glory and vengeance was fleeting.

The governor of Britannia, Suetonius Paulinus, who had been suppressing the Druid rebellion on the Isle of Anglesey, rushed into the fray to meet Boudicca in battle. His legions included the XIV Gemina, XX Valeria Victrix, and the II Augusta.

Boudicca must have known that they could not win against three legions, but rather than submit to Rome, she and her army met them head-on in the Battle of Watling Street. Despite the Romans being outnumbered, the legions’ discipline and Suetonius’ generalship won the day, and the Queen of the Iceni died by poison before being taken.

The Boudiccan rebellion was over, but like the Spartacan revolt during the Roman Republic, it left a mark on the Roman psyche, and the battle cry of the Iceni queen would reverberate for generations to come.

Boudicca, for me, is the epitome of the Celtic warrior queen. She stood up to the might of Rome, and became an important cultural symbol for the United Kingdom in later centuries.

What we know of her comes only from the writings of the Roman conquerors, but her deeds speak for themselves!

If you are interested in reading a great series of novels about the Boudiccan rebellion, I recommend Manda Scott’s wonderful Boudicca series, beginning with the first book, Dreaming the Eagle.

Julia Domna

A.D. 160 – 217

Julia Domna, Empress of the Roman Empire and wife of Septimius Severus, may not be on your own list of outstanding women of history, but she is someone I have developed a deep respect for over the years.

Those of you who are familiar with the Eagles and Dragons series will know that Julia Domna plays a prominent role in the novels. Having researched and written about her for so long, I feel like I have developed a grasp of her role as empress at a time when the Roman Empire was at its greatest extent.

She appears as one of the strongest women in Rome’s history, an equal partner in power with her husband who heeded her advice but also respected her.

Julia Domna was the first of the so-called ‘Syrian women’, she and her sisters hailing from Antioch where their father had been the respected high priest of Baal at Emesa (Homs in modern Syria).

Julia Domna was also highly intelligent, known as a philosopher, and had a group of leading scholars and rhetoricians about her. They came from around the Empire to be a part of her circle or salon, to win commissions from her. Her strength also bought her a great many enemies, including the Praetorian Prefect and kinsman to Severus, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus. The conflict between the Empress and the Prefect of the Guard is something that is explored a good deal in Children of Apollo and Killing the Hydra.

Not only did Julia Domna carry on the tradition of the strong, involved Roman empress that was begun by Livia Drusilla, she did so perhaps with an openness that gained her some loyal followers. Despite the fact that she was not Roman, she had earned a great deal of respect across the Empire.

Sadly, her sons Caracalla and Geta proved to be lesser mortals than their mother, but she helped to ensure that the Severan dynasty weathered the threats from outside, and in, for a time, paving the way for her sister Julia Maesa, and her neice, Julia Mamaea, both of whom followed in her footsteps as strong, ruling women.

If you would like to read more about Julia Domna and the Severans, be sure to read the blog post by CLICKING HERE. In addition to the Eagles and Dragons series, I highly recommend Michael Grant’s excellent book The Severans: The Changed Roman Empire.