One of the great things about reading and writing historical fiction is that one is given the chance to journey to a time and place far away from the modern world.

In this fourth part of The World of A Dragon among the Eagles, we’re going on location to some of the places where the action takes place, some of which, sadly, are still making headlines today.

This won’t be an in-depth look at these ancient cities, for their histories are long and varied, and they each deserve their own a book. Here, we’re just going to take a brief look at their place in this story.

Sites where A Dragon among the Eagles takes place

The first third of A Dragon among the Eagles takes place in Rome, then Athens, and a little at Amphipolis which has gained recent fame for the massive tomb and the excavations there which have been linked to the period of Alexander the Great.

However, we are not going to look at Rome and Athens, as we visit those cities much more in Children of Apollo and Killing the Hydra, the sequels to A Dragon among the Eagles. If you would like to read more about Amphipolis, you can read this BLOG POST HERE.

For this blog, we are mainly concerned with the cities where Lucius Metellus Anguis, our protagonist, gets his first taste of war with the Legions.

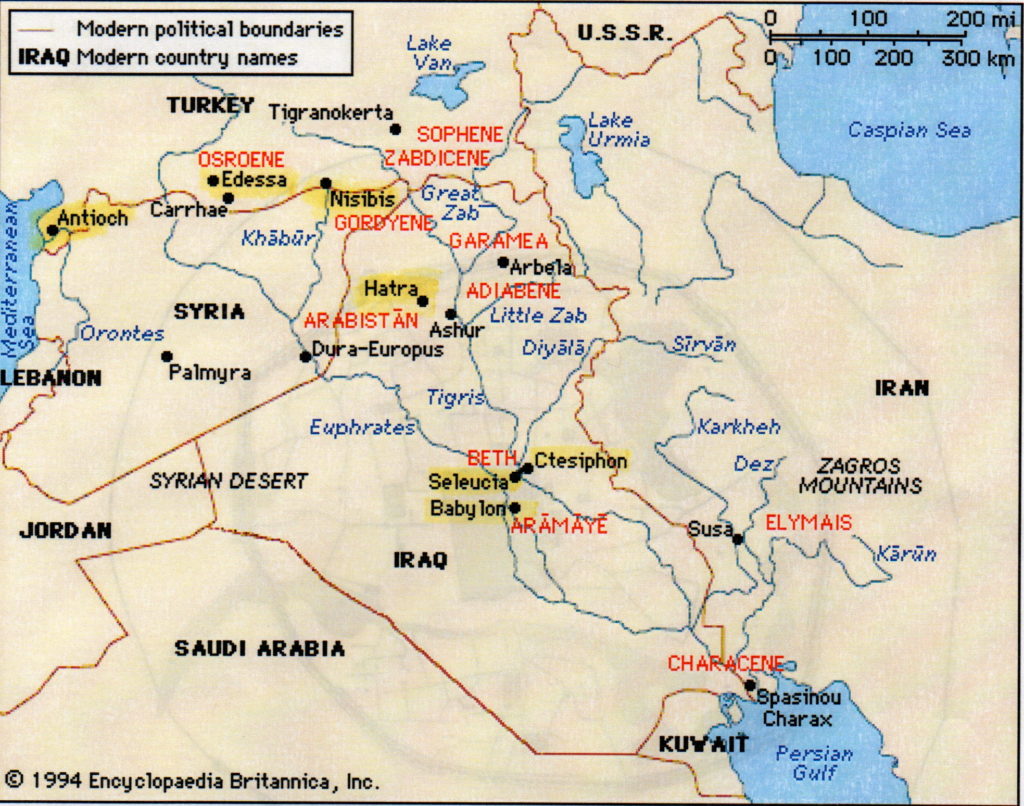

Mesopotamia is said to be the cradle of civilization, a land of alternating fertility and desert where the first cities were built, and empires made. It also was, and is, a land of war, a land of terrible beauty.

Trooper in modern Iraq

For millennia, successive civilizations have fought over this rich land, a land from which Alexander the Great had decided to rule his massive empire.

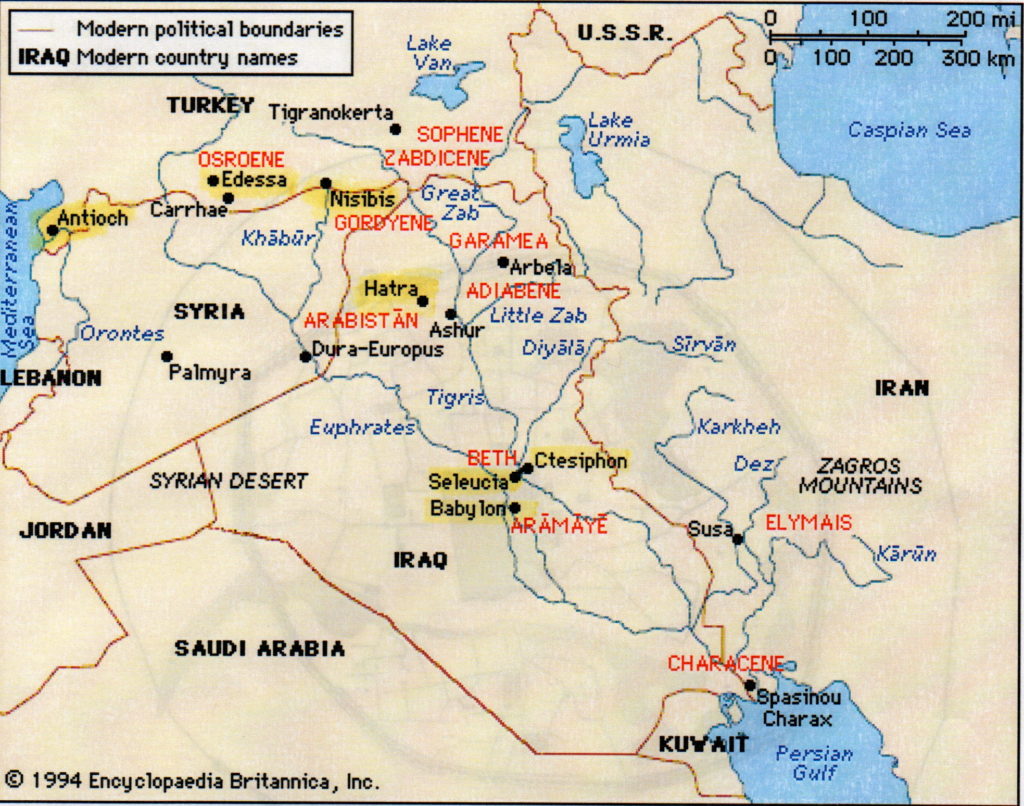

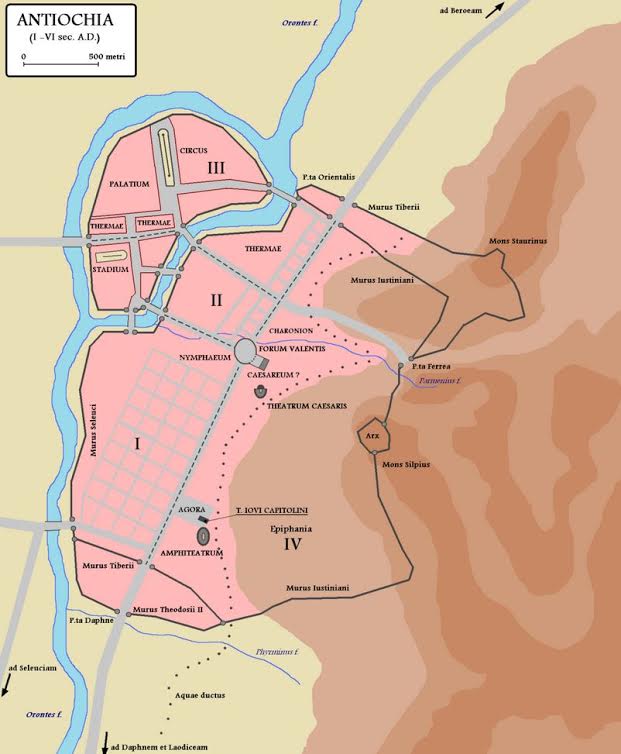

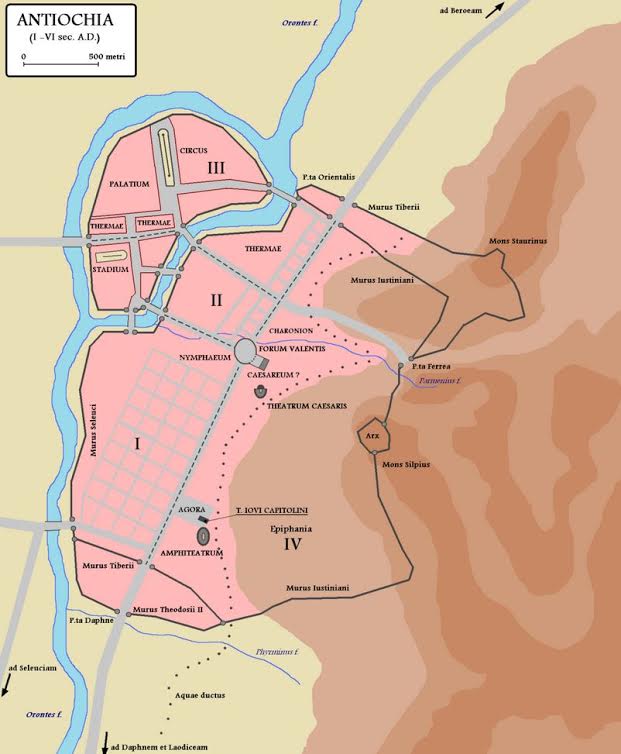

In A Dragon among the Eagles, Lucius Metellus Anguis’ legion arrives at the port of Antioch where Emperor Severus has assembled over thirty legions on the plains east of the city.

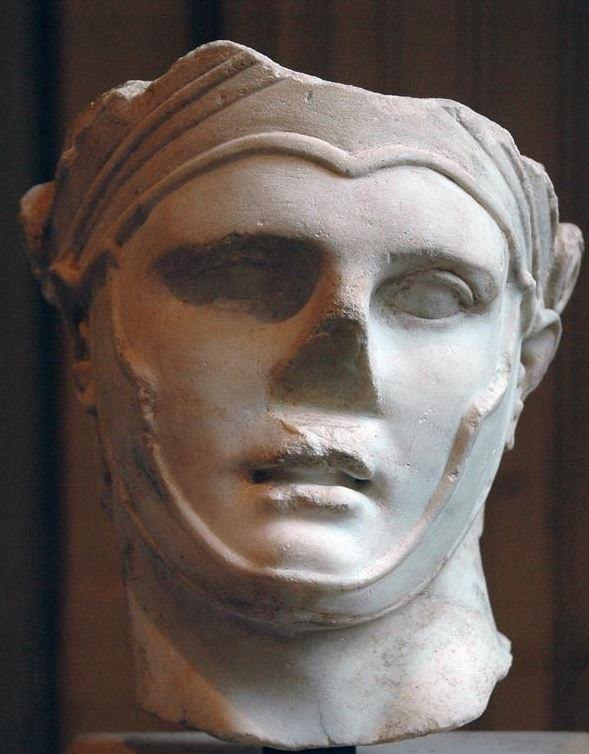

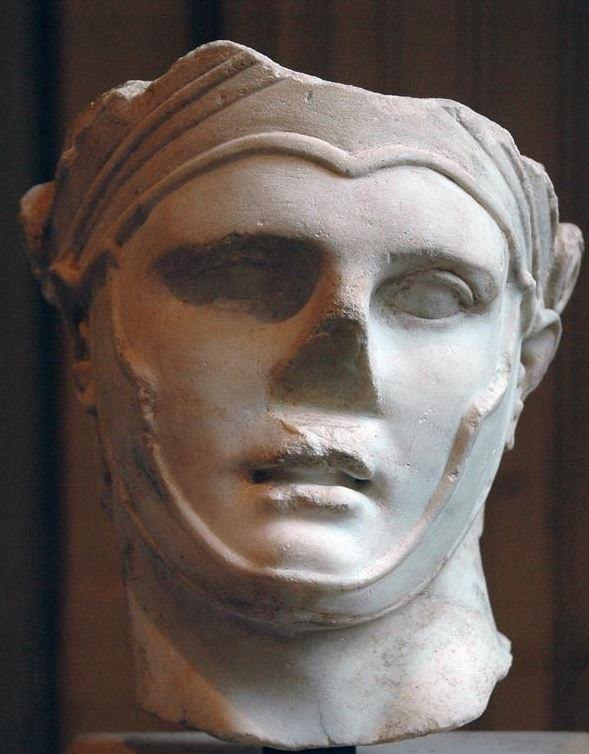

Antioch, which was then located in Syria, now lies in modern Turkey, near the city of Antyaka. It was founded in the fourth century B.C. by one of Alexander’s successor-generals, Seleucus I Nicator, the founder of the Seleucid Empire.

Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus named this city after his son, Antiochus, a name that would be taken by later kings of that dynasty.

Antioch was called the ‘Rome of the East’, and for good reason. It was rich, mostly due to its location along the Silk Road. Indeed, Antioch was a sort of gateway between the Mediterranean and the East, with many goods, especially spices, travelling through it. It is located on the Orontes river, and overlooked by Mt. Silpius.

Antioch in the Roman Empire

In the book, we catch a glimpse of this Ancient Greek city that was greatly enhanced by the Romans who saw much value in it. Actually, most of the development in Antioch took place during the period of Roman occupation. Enhancements included aqueducts, numerous baths, stoas, palaces and gardens for visiting emperors, and perhaps most impressive of all, a hippodrome for chariot racing that was 490 meters long and based on the Circus Maximus in Rome.

Antioch, during the late second century A.D., rivalled both Rome and Alexandria. It was a place of luxury and civility that was in stark contrast to the world of war where the legions were headed.

Some ruins of Nisibis today

In writing A Dragon among the Eagles, I have followed the itinerary presented to us by Cassius Dio, the main source for this period in Rome’s history and the Severan dynasty. So, the order in which we are looking at these locales is roughly the order in which Severus’ legions are supposed to have attacked them.

The first real battle in the book, and the first time our main character experiences battle, is at the desert city of Nisibis.

At the time, Nisibis was under Roman control. However, that control was about to break according to Dio, as the Romans inside were just holding onto it. This is due mainly to the leadership of the Roman general, Maecius Laetus, whom we meet in the story.

Laetus managed to hold the defences of Nisibis until Severus’ legions showed up, and was hailed as a hero for it.

Nisibin Bridge – Gertrude Bell’s caravan crossing bridge.

Nisibis was situated along the road from Assyria to Syria, and was always an important centre for trade. This was the only spot where travellers could cross the river Mygdonius, which means ‘fruit river’ in Aramaic. Today it is located on the edge of modern Turkey.

Early in its history, Nisibis was an Aramaen settlement, then part of the Assyrian Empire, before coming under the control of the Babylonians. In 332 B.C. Alexander the Great, and then throughout the Roman-Parthian wars, it was captured and re-captured, over and over.

Such is the fate of strategically placed settlements, especially when they are located along the Silk Road.

Ruins of Edessa

From the bloody fighting in Nisibis, Severus’ forces then moved into the Kingdom of Osrhoene and the upper Mesopotamian city of Edessa, located in modern Turkey.

Edessa was originally an ancient Assyrian city that was later built up by the Seleucids.

Edessa’s independence came to an end in the 160s A.D. when Marcus Aurelius’ co-emperor, Lucius Verus, occupied northern Mesopotamia during one of the Roman-Parthian wars.

From that point on, Osrhoene was forced to remain loyal to Rome, but things changed when the civil war broke out between Severus, Pescennius Niger, and Clodius Albinus. Osrhoene threw their support behind Niger, who was then governor of Syria.

When Severus came out the victor in the civil war, it was inevitable that Edessa and Osrhoene would have to face the drums of war.

Edessa was where King Abgar of Osrhoene, who was sympathetic to the Parthians, was holed up as Severus’ legions advanced.

King Abgar of Osrhoene and Commodus

One has to wonder what King Abgar was thinking as Severus approached this ancient city. Whatever it was, and whatever he said to the Roman Emperor when he arrived, it must have been acceptable, for Abgar was permitted to keep his throne as a client king of the Empire.

There was a siege, but it seems that with King Abgar accepting Rome’s overlordship, and Severus’ need to move south, this is why the Osrhoenes escaped any large scale retribution.

In a way, it was not so for Lucius Metellus Anguis, for whom Edessa proves to be a harsh and enlightening experience.

At this time, Septimius Severus had his sights set on southern Mesopotamia and the great cities of Seleucia, Babylon, and the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon.

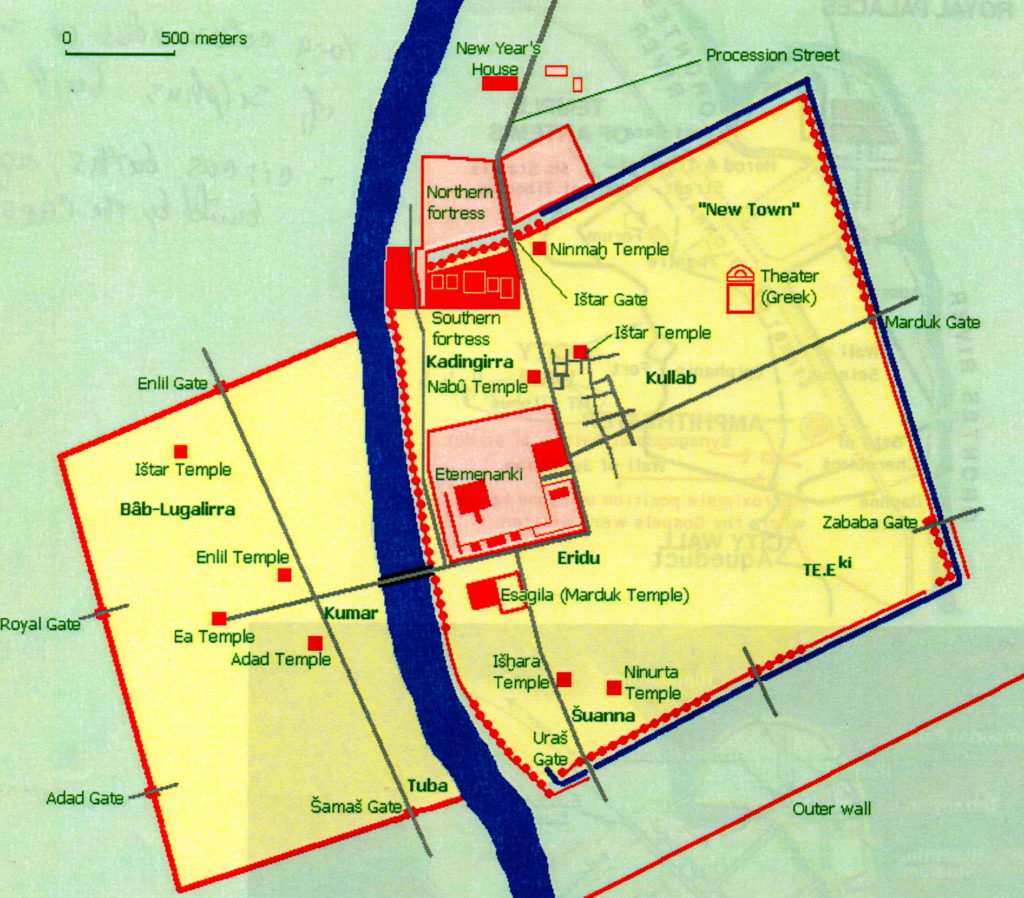

Ancient Babylon

The legions made their way south, directly for Seleucia-on-Tigris.

Seleucia, as the name suggests, was built by the Seleucus I Nicator in 305 B.C. as the capital of his empire. It was located sixty kilometers north of Babylon, and just across the Tigris River, on the west bank, from Ctesiphon. Today, Seleucia is located in modern Iraq, thirty kilometers south of Baghdad, and in its day, it was a major city in Mesopotamia.

It was a great Hellenistic city in the third and second centuries B.C., with a rich mixture of Greco-Mesopotamian architecture, and walls enclosing a full 1,400 acres as well as a population of 60,000 people.

When the Parthians took Seleucia, the capital was moved across the river to Ctesiphon and, though the city remained in use and inhabited, it went into a slow decline.

During the Roman-Parthian wars, Seleucia was burned by Trajan, rebuilt by Hadrian, and then destroyed again. Like a battered boxer with heart, it kept rising from the ground until there was no more will to keep it alive.

By the time Severus’ legions were marching on Seleucia, the Parthians had abandoned it completely, giving the Romans a foothold on the Tigris River, opposite their capital.

Seleucia on Tigris c.1927

Ctesiphon would have to wait, however, for there was another magnificent and symbolic prize within Severus’ grasp at that time – Babylon.

Alexander entering Babylon (Charles Le Brun)

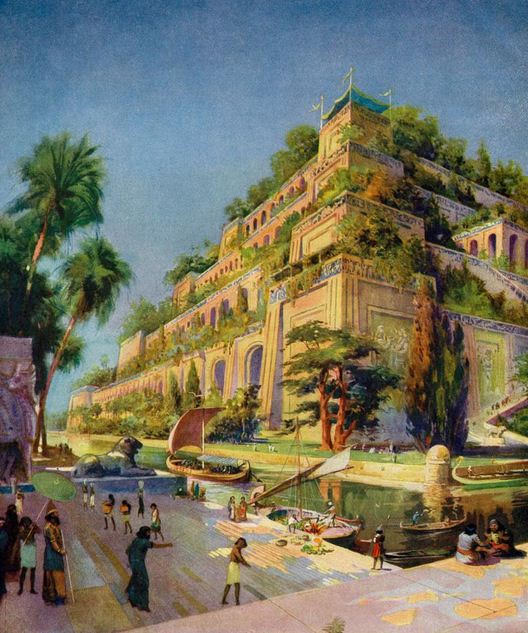

I find that when I utter the name of Babylon, I get chills. Think about it, this is one of the most famous of ancient cities! This was the place that welcomed Alexander the Great with open arms and triumph, the place from which he had decided to rule his titanic empire, and the place where he died.

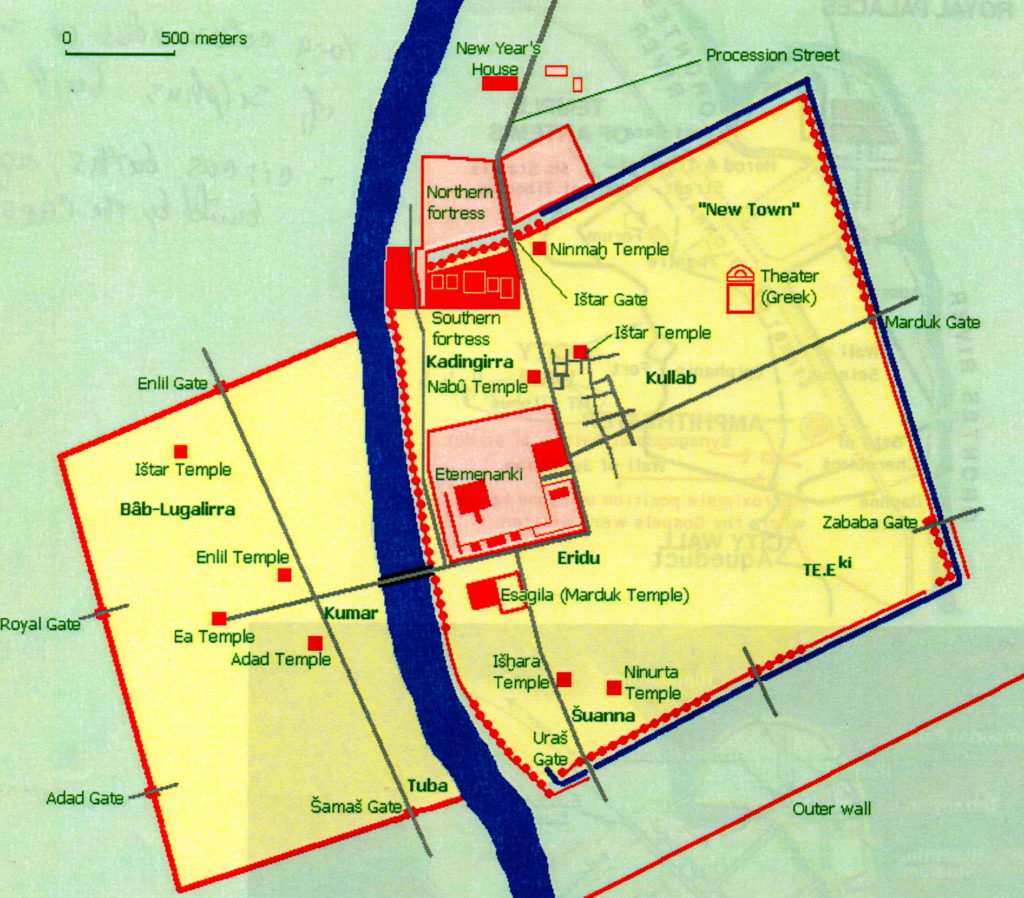

Babylon was located on the fertile plain between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Actually, part of it was built over the Euphrates.

The original settlement of Babylon is said to date to about 2300 B.C when it was part of the Semitic Akkadian Empire. It was fought over and rebuilt, and in about 1830 B.C. it became the seat of the first Babylonian dynasty.

From about 1770 B.C. to 1670 B.C. Babylon was the largest city in the world with a population of over 200,000.

Perhaps the most famous period in Babylon’s long and ancient history is during what is known as the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626-539 B.C.), and especially the reign of King Nebuchadnezzar II (605-562 B.C.)

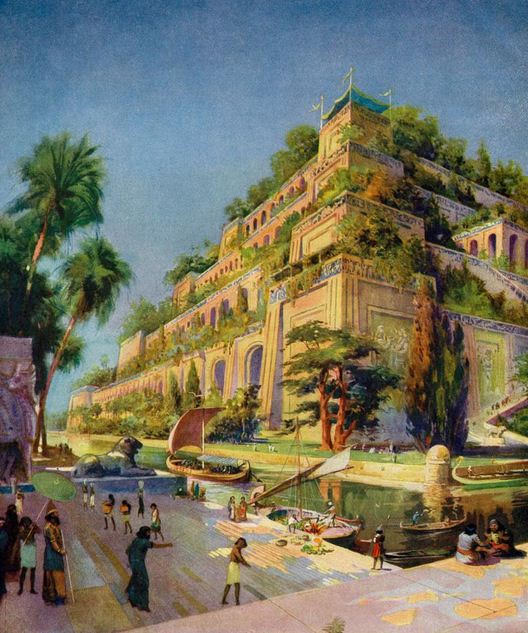

Then Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Nebuchadnezzar was a great builder, and it was he who made Babylon one of the most beautiful cities of the ancient world, home to one of the Seven Wonders.

He built the famed Hanging Gardens of Babylon for his Median wife who missed the lushness of her homeland, and he also constructed the giant ziggurat of Etemenanki beside the temple of Marduk.

Babylon at this time must have been a sort of paradise on earth with the ziggurat as the doorway to the heavens. The walls of the city too, were so big that it was said that two chariots could pass each other as they drove along the top of the walls.

Ishtar Gate of Babylon at Pergamon Museum Berlin

When the Seleucids came onto the scene and Babylon’s power and beauty faded into history, the population was moved to Seleucia, one supposes to bolster the economy of the great new capital envisioned by Seleucus I.

There was a lot of history at Babylon, and it’s not improbable that all the Romans who marched through there thought of Alexander as they approached, including Severus.

But Babylon was a very different place when the legions marched on it late in A.D. 198.

Just as Seleucia had been abandoned, so too was Babylon. And so, with barely a drop of blood being shed, the Romans walked into this ancient city of faded glory in stern silence, their prize almost too easily won.

Ruins of Babylon (Wikimedia Commons)

It was time for the real battle.

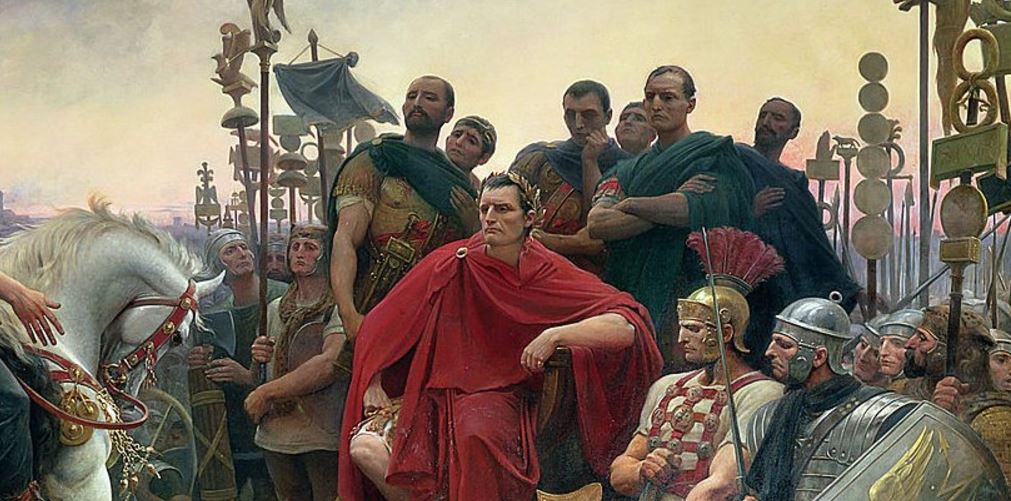

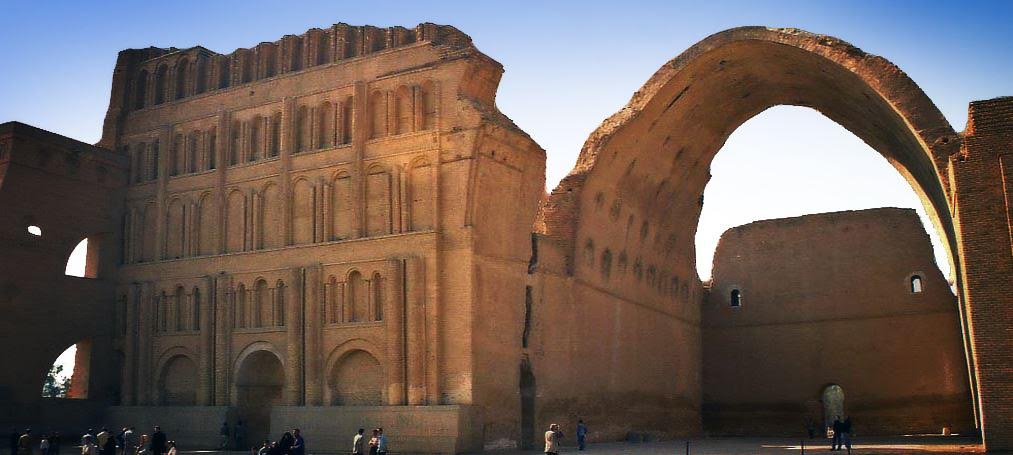

With Seleucia and Babylon basically given over to Rome and Severus’ legions, the forces of Rome and Parthia converged on the capital of Ctesiphon.

This time, the Parthians were waiting.

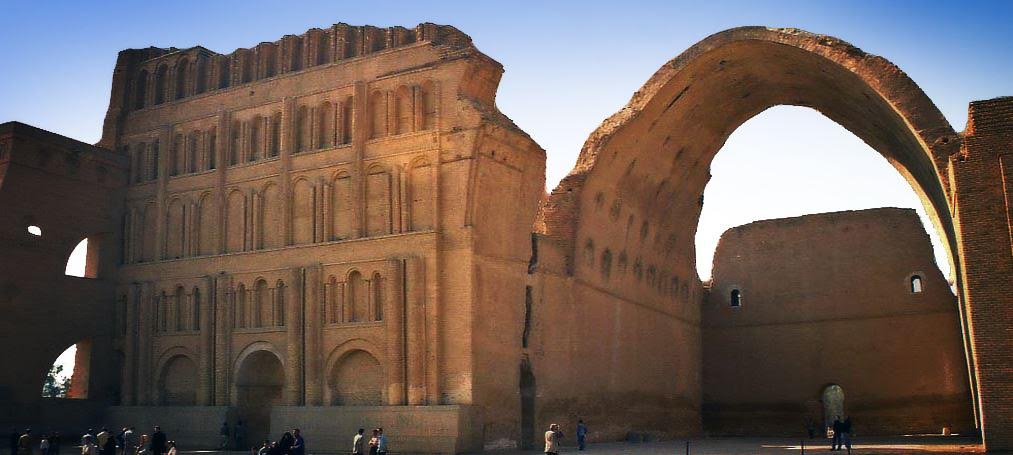

Ctesiphon, compared to the other cities we have seen, was a relatively new settlement on the east bank of the Tigris River, facing Seleucia. It was built around 120 B.C. on the site of a military camp built by Mithridtes I of Parthia. At one point in time, it merged with Seleucia to form a major metropolis straddling the river.

Ctesiphon’s ruins today, including the great audience hall.

During the Roman-Parthian wars, Ctesiphon did not have an easy time of it. It was captured by Rome five times in its history, the last time by Septimius Severus who burned it to the ground and enslaved much of the population.

The Greek geographer, Strabo, describes the foundation of Ctesiphon here:

In ancient times Babylon was the metropolis of Assyria; but now Seleucia is the metropolis, I mean the Seleucia on the Tigris, as it is called. Nearby is situated a village called Ctesiphon, a large village. This village the kings of the Parthians were wont to make their winter residence, thus sparing the Seleucians, in order that the Seleucians might not be oppressed by having the Scythian folk or soldiery quartered amongst them. Because of the Parthian power, therefore, Ctesiphon is a city rather than a village; its size is such that it lodges a great number of people, and it has been equipped with buildings by the Parthians themselves; and it has been provided by the Parthians with wares for sale and with the arts that are pleasing to the Parthians; for the Parthian kings are accustomed to spend the winter there because of the salubrity of the air, but they summer at Ecbatana and in Hyrcania because of the prevalence of their ancient renown.

Being built by the Parthians, Ctesiphon, unlike Seleucia, Babylon, or the other places we have discussed, was a Parthian invention. Probably the greatest structure of this capital was the great, vaulted audience chamber, or hall, which seems to be all that remains today. In truth, there is very little information on other structures within Ctesiphon itself.

Ctesiphon from the air

The final sack of Ctesiphon by Severus’ legions in A.D. 197 was a brutal affair, and one that ended that city and provided the death blow to the Parthian Empire.

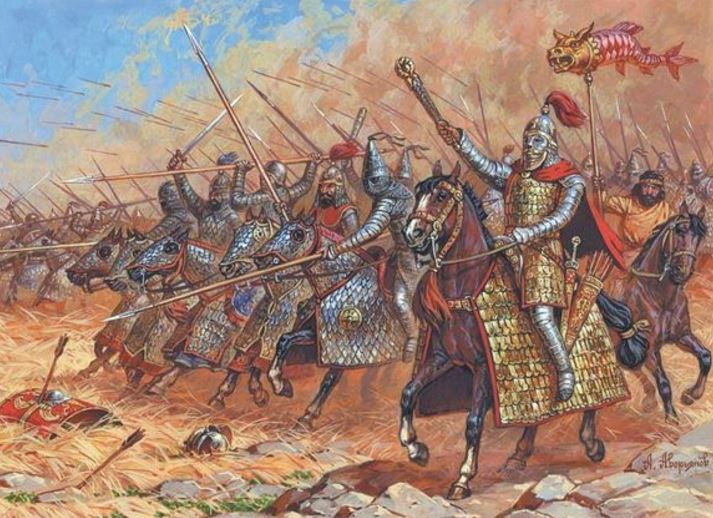

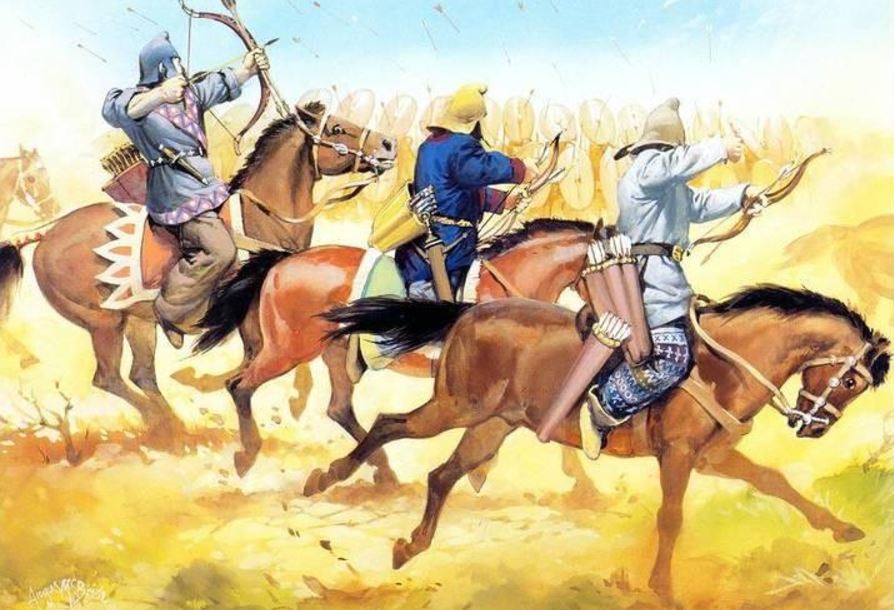

In A Dragon among the Eagles, the Roman attack on Ctesiphon is one of the major battle scenes which I had envisioned a long time ago. Imagine, almost thirty legions lined up on the other side of the river with the entire force of Parthian horse archers and heavy cataphracts awaiting them.

The Romans had to cross the river, gain a beachhead, and then push forward. In the end, Rome prevailed, but at great cost to the troops.

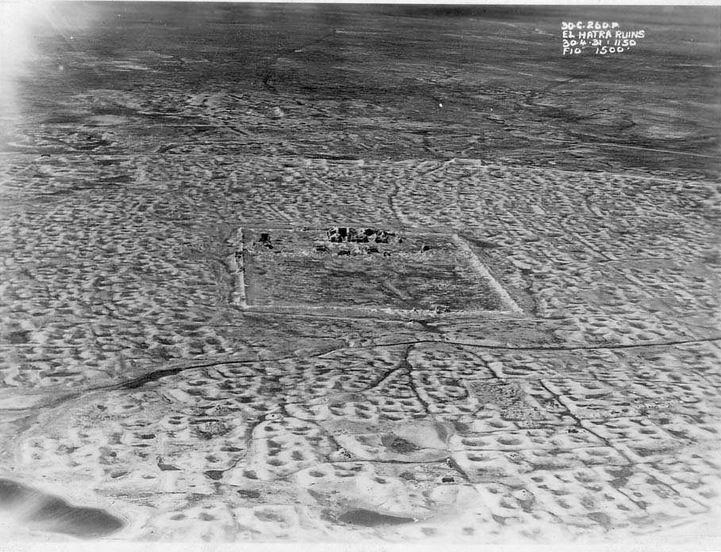

One would have thought that with the sacking of the Parthian capital, all would be finished, but there was another score for Rome to settle, another city to take – the desert city of Hatra.

Hatra is located in modern Iraq, about 290 kilometers north of Baghdad, on the Mesopotamian desert, far from either the Tigris or Euphrates. It was built by the Seleucids, those Hellenistic giants we’ve heard so much about, around the third century B.C.

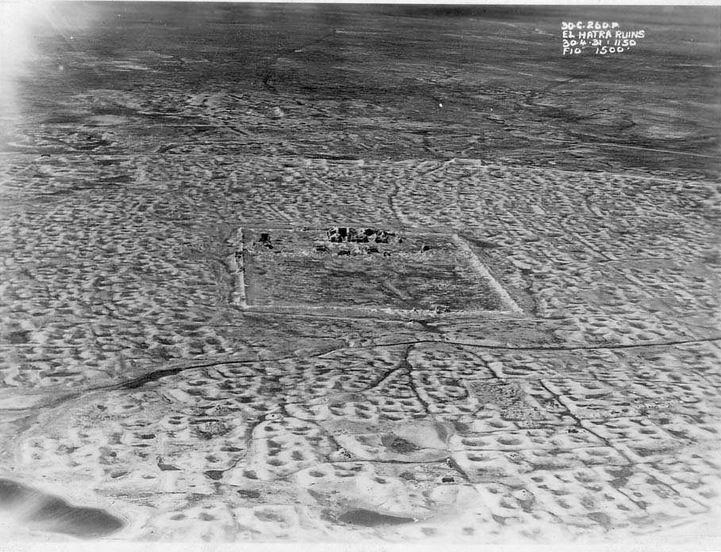

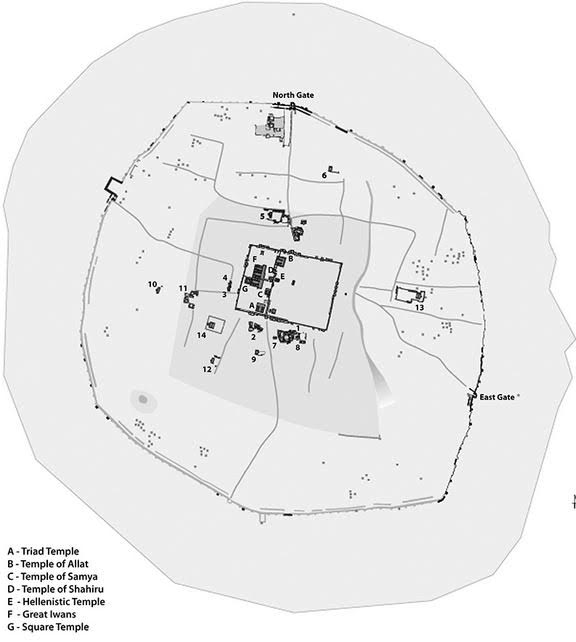

Hatra old survey aerial photo

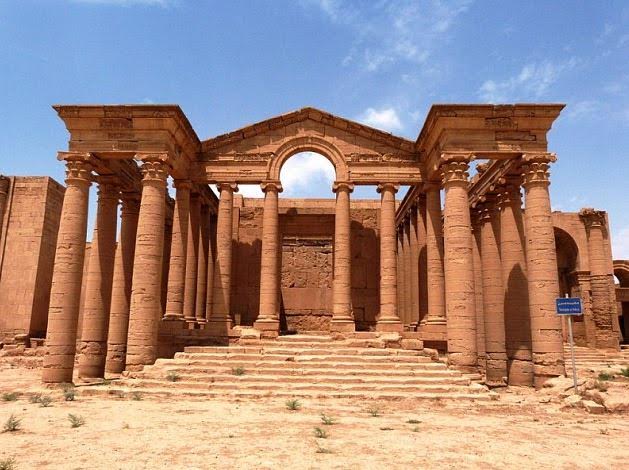

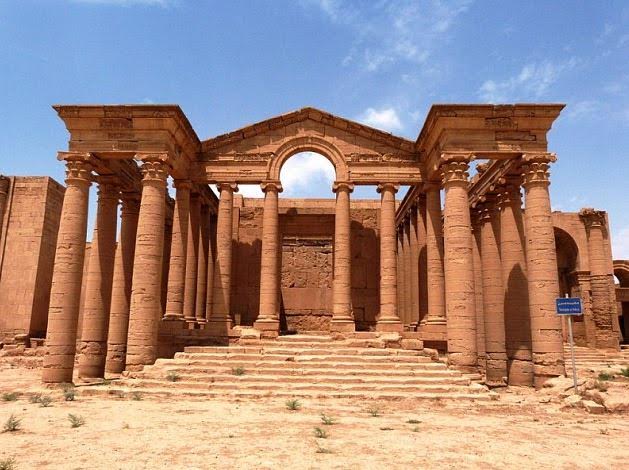

It flourished under the Pathians too as a center of religion and trade during the first and second centuries A.D. What is fascinating about Hatra is the harmony and religious fusion it represented. This remote desert city was a place where Greek, Mesopotamian, Canaanite, Aramean, and Arabian religions lived peacefully side-by-side. And for 1,400 years it was protected and preserved by Islamic regimes, until it was destroyed in 2015.

It was the best-preserved Parthian city in existence.

Hatra before the 2015 destruction

When Septimius Severus turned his attention on Hatra after the fall of Ctesiphon, it was with a goal of doing what no other Roman, even Trajan, had been able to do.

It was personal too, for Hatra and its ruler, Abdsamiya, had supported Pescennius Niger against Severus in the civil war.

But there were a few reasons Hatra had withstood Roman sieges, including the two attempted by Severus in his Parthian campaign.

First of all, Hatra was remote, stranded out in the desert with its own water source within the walls, but none without. The nearest water was over forty miles in any direction. A legion could only march a maximum of twenty-five miles in one day. So, thirst for those laying siege was a big factor.

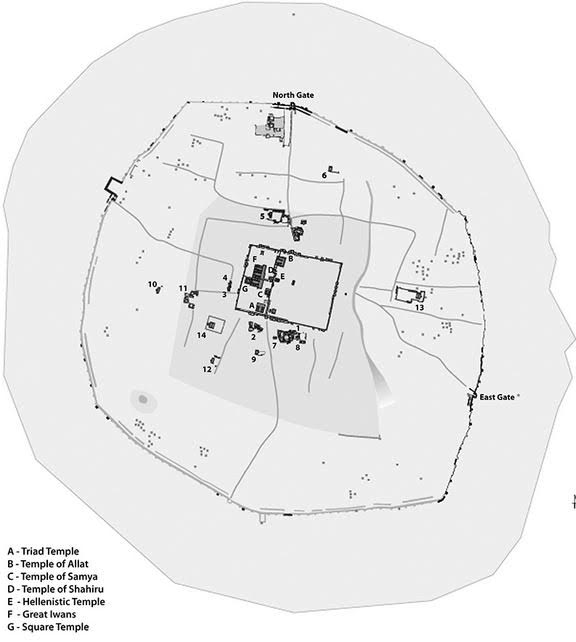

Then there were the walls – two of them. Hatra was protected by immense, circular, inner and outer walls, the diameter of which was 2 kilometers, or 1.2 miles. Along these massive walls were 160 towers, making this island fortress of the sand seas no easy target.

Hatra Map (with temples labelled)

At Hatra’s heart were the sacred buildings of the gods of various religions, gods whom many believed protected the city from attack.

The temples within Hatra covered a total of 1.2 hectares, and that area was dominated by the Great Temple of Bel which was about 30 meters high.

Hatra withstood two major attacks by Roman emperors, Trajan and Severus. Every time, Hatra’s walls, and her gods, turned Rome back.

Cassius Dio describes Severus’ last siege of Hatra:

He himself made another expedition against Hatra, having first got ready a large store of food and prepared many siege engines; for he felt it was disgraceful, now that the other places had been subdued, that this one alone, lying there in their midst, should continue to resist. But he lost a vast amount of money, all his engines, except those built by Priscus, as I have stated above, and many soldiers besides…

When the walls were breached, Severus gave the Hatrans time to consider surrender, as he respected the religious importance of the place, especially the temple of the Sun God. But the Hatrans were stubborn, and the troops were fed up:

Thus Heaven, that saved the city, first caused Severus to recall the soldiers when they could have entered the place, and in turn caused the soldiers to hinder him from capturing it when he later wished to do so [threat of mutiny].

Once again, Hatra resisted being conquered by Rome, making it the only place Severus’ legions were not able to take.

One of Hatra’s many magnificent temples

It is sad that, in light of the events of 2015, it seems Hatra’s gods finally deserted it.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this march with the legions! In the next post, we’ll be going somewhere more civilized – the City of Alexander the Great!

This past week has been a good one for A Dragon among the Eagles, for in the UK it became an Amazon #1 Bestseller in three categories, including Historical Fantasy. It is also climbing in the Amazon US charts too, so thank you to everyone for supporting the book!

For those of you who prefer to read paperbacks, A Dragon among the Eagles is now available in trade paperback format from either Amazon or Create Space.

And as ever, thank you for reading.