Greetings readers and fellow history-lovers!

I hope that you have all had a good and safe summer where you are, despite the chaos that has been gripping our shared world.

My apologies for the extended silence on the blog, but the focus these last several weeks has been on writing the next Eagles and Dragons novel, The Blood Road, and I’m happy to report that the first draft is almost finished.

This leads us to the subject of this new blog post which was inspired by one of the settings in The Blood Road. In this instance, I’m referring to ancient Delphi.

The archaeological site of Delphi as seen from above the theatre, with the temple of Apollo below.

Delphi is one of my favourite archaeological sites in Greece, and I’ve visited it several times (you can read about one of my visits HERE). It has never really made an appearance in my fiction except very briefly in The Dragon: Genesis, and Killing the Hydra. I had planned on visiting this summer and filming a documentary there, but alas, those plans have been put on hold.

Delphi is one of those places that was sacred to both the ancient Greeks and Romans. It symbolized more that just a place where Apollo had his most famous oracle – the Pythia – but was also a guiding light in the ancient world. The ‘Navel of the World’, as Delphi was known, also carried with it a philosophy for living, or rather a series of philosophies known as the Delphic Maxims.

The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy defines a maxim as a “simple and memorable rule or guide for living”. The Delphic Maxims were written and memorized by ancient students, discussed by philosophers, for hundreds of years.

In a way, this post is timely. It’s fitting that, during times of both physical, mental, and spiritual strain, we look elsewhere for some inspiration and guidance to get us through. Adversity can be a good thing that makes us stronger, but we all have a breaking point.

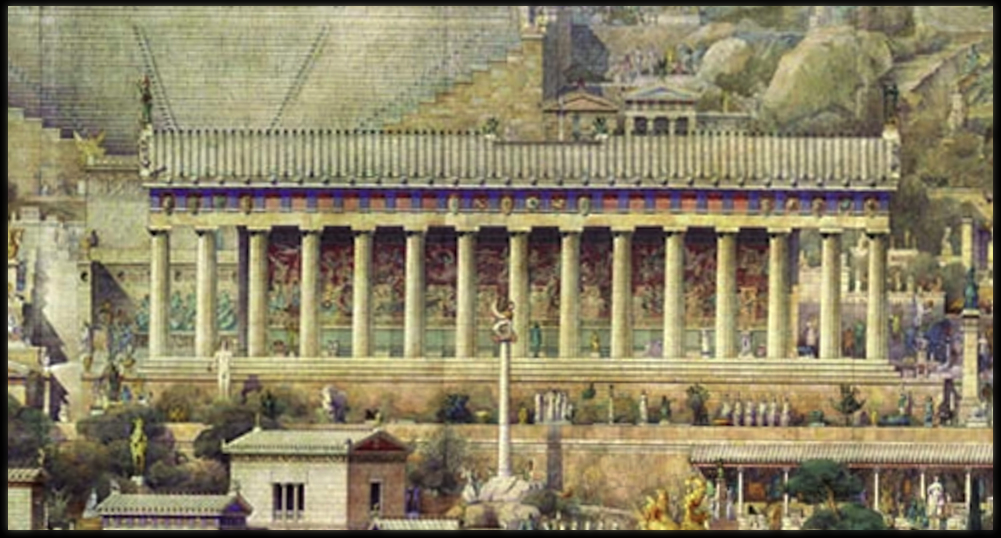

Temple of Apollo at Delphi, by Albert Tournaire (Wikimedia Commons)

Most of you will be familiar with the most famous of the Delphic Maxims, ‘Know thyself’. It, along with ‘Nothing in excess’ and ‘Surety brings ruin’, was inscribed on the pronaos, the entrance to the temple of Apollo at Delphi. These three maxims, especially the first, were discussed at length by some of the greatest philosophers of the ancient world, including Socrates and Plato in his many dialogues.

“Tell me, Euthydemus, have you ever been to Delphi?”

“Yes, certainly; twice.”

“Then did you notice somewhere on the temple the inscription ‘Know thyself’?”

“I did.”

“And did you pay no heed to the inscription, or did you attend to it and try to consider who you were?”

“Indeed I did not; because I felt sure that I knew that already; for I could hardly know anything else if I did not even know myself.”

(Socrates on ‘Know thyself’ in Xenophon’s Memorabilia 4.2.24)

During my research for The Blood Road, I’m a little embarrassed to admit that I discovered there were more than the three Delphic maxims mentioned above. There were, in fact, 147 of them!

Perhaps it was because I had not studied philosophy in depth at university that these were not brought to my attention, or that I just never dug deep enough, focussing, like most, on ‘Know thyself’. Whatever the case, this long list of maxims were important to ancient ways of thinking, and provided a moral code or principles for living that were taught to students and to be considered throughout a man’s life.

Apollo and the Pythia who uttered his prophecies to mortals

But where did the Delphic Maxims come from? Who came up with them?

There are two traditions or answers to this.

The first is that they were said to have been originally given by Apollo, through his oracle, the Pythia.

The second, as mentioned by several ancient writers, including Diogenes Laertius (3rd century A.D.) and Stobaeus (5th century A.D.) is that the Delphic Maxims were developed by the Seven Sages of ancient Greece. These seven men were philosophers and law-givers in the sixth century B.C.

In the fore-temple at Delphi are written maxims useful for the life of men, inscribed by those whom the Greeks say were sages… These sages, then, came to Delphi and dedicated to Apollo the celebrated maxims, “Know thyself,” and “Nothing in excess.”

(Pausanias, Description of Greece 10.24)

Who were these wise men that are frequently mentioned in ancient sources? Some of them you may recognize, but most you may not unless you have studied ancient Greek history in depth. Also, there is some disagreement among ancient sources about a few of the names. Nevertheless, here they are:

The first is Thales of Miletus (c. 624-546 B.C.). He is generally thought to be the first well-known Greek philosopher. He also wrote about the concept of philotimo which is a central theme of the Eagles and Dragons series. If you would like to read my previous post on philotimo and Thales of Miletus, you can check that out by CLICKING HERE.

The other commonly named men of the seven sages are Pittacus of Mytilene (c. 640-568 B.C.) who was a governor of Mytilene (Lesbos) who tried to curb the power of the nobility, and Bias of Priene (6th century B.C.) who was also a politician.

Oh, for the days when politicians were considered ‘wise men’ or ‘sages’!

Carrying on…

There was, of course, Solon of Athens (638-558 B.C.) whom many of you will know as the great lawmaker of Athens who helped to give form to Athenian democracy. Then, there was Chilon of Sparta (c. 555 B.C.) who was a Spartan ephor and politician who helped to militarize Spartan society.

When it comes to the fifth and sixth names on the ancient lists of the seven sages, there is some variation among the following names:

There is Cleobulus (c. 600 B.C.) who was a tyrant of Lindos and related to Thales, Periander of Corinthos (634-585 B.C.) who was a successful administrator in Corinth, Myson of Chenae (6th century B.C.) who was a Cretan or Laconian farmer, and finally, Anacharsis the Scythian (6th century B.C.) who travelled from what is today northern Iran to Athens where he made a surprisingly good impression on the normally xenophobic Greeks.

3rd century A.D. mosaic of the Seven sages with the muse, Calliope in the center. (Wikimedia Commons)

Such men were Thales of Miletus, Pittacus of Mytilene, Bias of Priene, Solon of our city, Cleobulus of Lindus, Myson of Chen, and, last of the traditional seven, Chilon of Sparta. All these were enthusiasts, lovers and disciples of the Spartan culture; and you can recognize that character in their wisdom by the short, memorable sayings that fell from each of them they assembled together

and dedicated these as the first-fruits of their lore to Apollo in his Delphic temple, inscribing there those maxims which are on every tongue—“Know thyself” and “Nothing overmuch.” To what intent do I say this? To show how the ancient philosophy had this style of laconic brevity; and so it was that the saying of Pittacus was privately handed about with high approbation among the sages—that it is hard to be good.

(Plato’s Protagoras, 343 a-b)

Whatever the true origins of the Delphic Maxims, it is clear that they were revered in the ancient world, and used by teachers, as the Roman writer Quintilian said of students, to “improve their moral core”.

The world could certainly use some of that today, no?

But what sorts of things do the Delphic Maxims say, instruct or advise?

Well, there is, to be honest, quite a bit of variation and, in looking at them, you can see how very laconic they are (hence the many references to their Spartan influence!). These short, punchy phrases give us a good idea of what the ideal moral code was in ancient Greece and even Rome and, though some may seem anachronistic to us today, many could certainly apply to our current world situation.

I won’t list them all here, but some of them make a whole lot of sense…

‘Obey the law’

‘Respect your parents’ (you parents out there will understand!)

‘Know by learning’

‘Listen and understand’

‘Pursue honour’ (remember Thales’ idea of philotimo)

‘Shun evil’

‘Look to the future’

and

‘If you have, give’

There are others that are of a highly religious theme, an aspect of life that many have lost today but which was central to ancient ways of thinking and living:

‘Pray for what is possible’

‘Respect the Gods’

‘Embrace your fate’

‘Exercise [religious] silence’

and

‘Do not wrong the Dead’

Then, there are some that may sound absurd to our modern minds:

‘Set out to be married’

‘Educate your sons’ (education is good, but what about our daughters?)

‘Control your wife’ (mine was not impressed with this one!)

and

‘Admire oracles’

But some of my favourites are those that could really guide us in these dark times of ours:

‘Listen and understand’

‘Exercise nobility of character’

‘Embrace friendship’

‘If you have received, give back’

‘Despise slander’

‘Shun violence’

‘Deal kindly with everyone’ (this one’s for you, Leon Logothetis!)

‘Pursue harmony’

‘Shun hatred’

and

‘Do not abandon honour’

There are others, but these are the ones that stand out to me at the moment.

2nd century B.C. inscription of some of the Delphic Maxims from a find in Afghanistan (Wikimedia Commons)

Perhaps the most resonant of the Delphic Maxims, however, are some of the final ones on the list…

‘Do as well as your mortal status permits’

and

‘At your end be without sorrow’

This last one hits particularly hard, especially when one actually thinks about one’s end being near, for it is really contingent on most of the other maxims.

A thoughtful life, well-lived, is a life without regret.

Would that we could all know and feel that when the time comes…

The sacred valley before Delphi