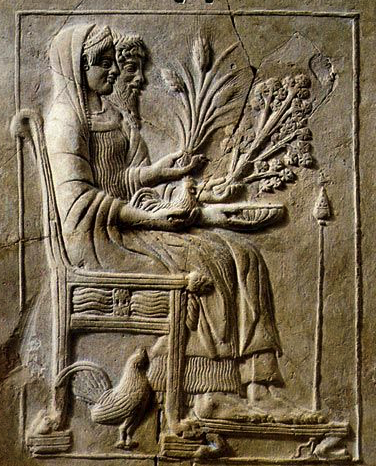

I begin to sing of rich-haired Demeter, awful goddess — of her and her trim-ankled daughter whom Aidoneus rapt away, given to him by all-seeing Zeus the loud-thunderer.(The Hymn to Demeter)

Greetings history-lovers.

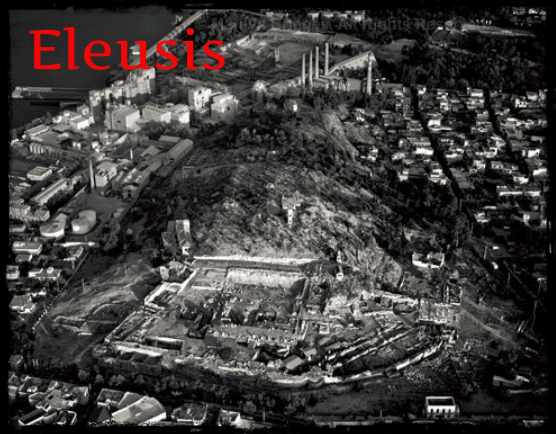

We’re going on a journey today to one of the most sacred sites of ancient Greece. It’s been a while since I took you on a site visit – we’ve already been to Olympia, Delphi, Nemea, Bassae, Brauron, Epidaurus, Delos and more – and so, the time has come for another.

Today we are going to briefly discuss the site, the history and mythology of ancient Eleusis (pronounced ‘Elefsis’), a site that was sacred for thousands of years right through the period of the Roman Empire, and which was where the Eleusinian Mysteries took place.

Eleusis is not just an ancient religious site and sanctuary. It’s much more than that. It’s a story of abduction, of a mother’s grief and her revenge, of overcoming the fear of death, and of hope for the future. Visiting this site is unlike any other. I hope you enjoy the journey…

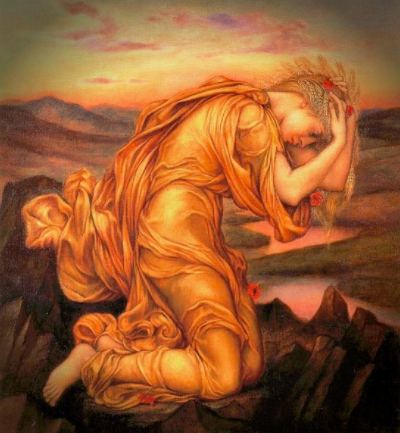

Apart from Demeter, lady of the golden sword and glorious fruits, she [Persephone] was playing with the deep-bosomed daughters of Oceanus and gathering flowers over a soft meadow, roses and crocuses and beautiful violets, irises also and hyacinths and the narcissus, which Earth made to grow at the will of Zeus and to please the Host of Many, to be a snare for the bloom-like girl — a marvellous, radiant flower. It was a thing of awe whether for deathless gods or mortal men to see: from its root grew a hundred blooms and is smelled most sweetly, so that all wide heaven above and the whole earth and the sea’s salt swell laughed for joy. And the girl was amazed and reached out with both hands to take the lovely toy; but the wide-pathed earth yawned there in the plain of Nysa, and the lord, Host of Many, with his immortal horses sprang out upon her — the Son of Cronos, He who has many names… He caught her up reluctant on his golden car and bare her away lamenting. Then she cried out shrilly with her voice, calling upon her father, the Son of Cronos, who is most high and excellent. But no one, either of the deathless gods or of mortal men, heard her voice, nor yet the olive-trees bearing rich fruit… (The Hymn to Demeter)

Rarely have I been to an ancient site as moving as Eleusis, modern Elefsina to the northwest of Athens. The memory of it haunts me still.

I left our home in the UK to visit family in Athens for the Christmas holidays. The celebrations were finished, Christmas and New Year having passed in a flurry of food and drink, and we were looking for sites to visit.

We decided on Eleusis.

Admittedly, I did not know a lot about the site at the time, but I had read about its importance, heard whispers of the Mysteries in some of the books I had read.

It was a cold and rainy day in January when we set out on the drive from Athens. I expected to get out into the countryside at some point, as we so often do when visiting sites, but the entirety of the drive, we were surrounded by the urban world, the sea occasionally coming into view.

Before I knew it, we were there, tightly parked on a dirty side street in front of low apartment buildings and homes. I got out of the car and looked around. Across the way there was a fence that surrounded a vast archaeological site, but first my eyes were drawn to the signs of industry not far off – cranes and shipyards, and shipping containers stacked to the sky. I also noted that average private homes looked directly onto the archaeological site.

This can’t be the site of the Eleusinian Mysteries, can it? I thought. But it was.

It is truly jarring to come to such an ancient site, revered throughout the ancient world, to see the dirty, modern world laying siege to it, crushing its edges like a polluted sea around an island paradise.

We made our way to the entrance, purchased our tickets and a guide book, and entered the site.

When I visit a site, more often than not, I don’t think first of the physical remains I’m about to see. I think of the story behind the place, the events that occurred there. And so, first, we should look briefly at the story of Eleusis…

Demeter, Goddess of the harvest and agriculture, and sister of Zeus, lost her daughter, Persephone (also known as ‘Kore’). Hades (Pluto), god of the Underworld, had fallen in love with the young girl and abducted her, taking her back to his kingdom beneath the earth.

Demeter, despairing for the loss of her daughter, wandered the earth until she came to Eleusis. She was found weeping at a well there, near a doorway to the Underworld. The local king built her a temple at Eleusis and the goddess, angry at both gods and men for the loss of her daughter, locked herself away in the temple.

Drought and famine ravaged the land and mortals began to die in large numbers. And so, Zeus intervened with Hades on Demeter’s behalf and it was agreed that Persephone would be permitted to leave the Underworld for a part of the year while dwelling there for the four months of winter when the land is dead and cold.

Once the bargain was struck, Demeter emerged from her temple to teach the Eleusinians special rites for their morals as well as ways to cultivate the land.

Bitter pain seized her heart, and she rent the covering upon her divine hair with her dear hands: her dark cloak she cast down from both her shoulders and sped, like a wild-bird, over the firm land and yielding sea, seeking her child. But no one would tell her the truth, neither god nor mortal men; and of the birds of omen none came with true news for her. Then for nine days queenly Deo[Demeter]wandered over the earth with flaming torches in her hands, so grieved that she never tasted ambrosia and the sweet draught of nectar, nor sprinkled her body with water.(The Hymn to Demeter)

It’s a tragic tale, in true Greek fashion. But, before we go any further, we should discuss a little about the history of this site.

Eleusis, where it stands in the southwest corner of the Thriasian Plain, has been inhabited since the Middle Helladic period (1900 – 1600 B.C.). It was during the later Mycenaean period that the first temple of Demeter was built, during the reign of the legendary king, Celeus.

Eleusis was an important strategic site on the route from Athens to the Peloponnese, Boeotia, and northern Greece. Over time, there were a series of conflicts between the Eleusinians and Athens until the time of King Theseus (yes, that Theseus) when it was subjugated and became the demeof the tribe of Hippothontis, the latter remaining the official keepers of the Mysteries there.

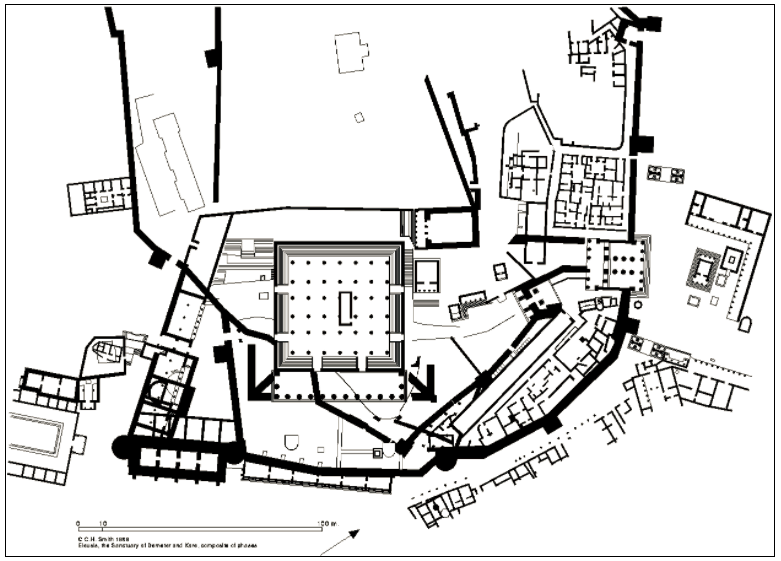

During the Geometric period (1100-700 B.C.), which came after the Trojan War, the cult of Demeter grew in popularity. It was in 760 B.C., the year of the fifth Olympiad, that there was a famine in Greece, and at the behest of the Oracle of Delphi, a sacrifice and festival to Demeter were begun at Eleusis. At this time a large wall was built around the sanctuary, enclosing the Plutoneion and the Telesterion. We’ll discuss these two structures shortly.

Some believe that it was this period which may have been the beginning of the Pan-Hellenic Eleusinian cult. Subsequently, during the time of Solon (c. 600 B.C.) the Eleusinian Mysteries were made one of the sacred Athenian festivals and a new, larger Telesterion and open courts were built for ceremonies to hide the rituals from the eyes of the uninitiated.

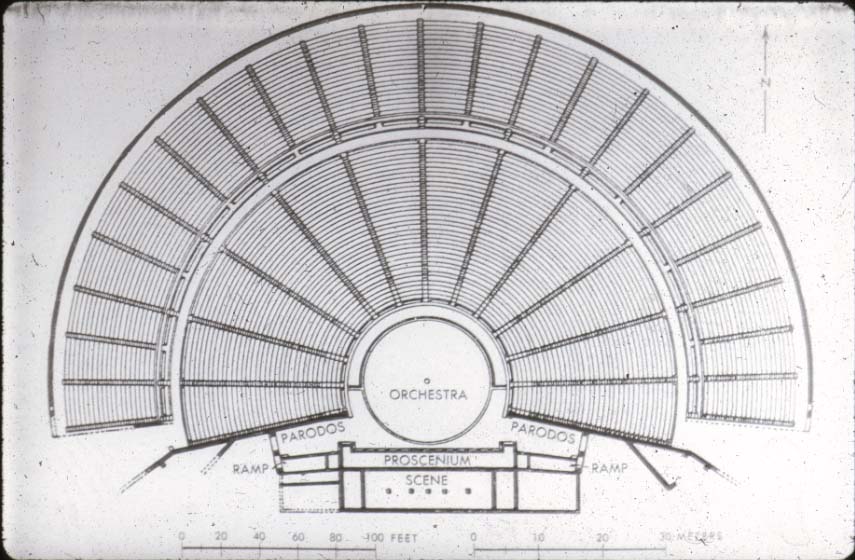

The Telesterion (which means ‘where ceremony takes place’) itself was a large structure with six entrances (two on three sides) where the rituals and ceremonies of initiates took place. During the rule of Pisistratus and his family (c. 550-510 B.C.), the Telesterion was enlarged even more and made on a square plan, the walls also being improved upon to make the sanctuary a sort of stronghold.

Sadly, during the Persian wars, the sanctuary of Eleusis was destroyed by the troops of Xerxes and Mardonius around 479 B.C. It was rebuilt by Cimon after the battle of Plataea when the Persians were defeated.

In the second half of the fifth century, Eleusis was included in the building programs of Pericles and, once more, the Telesterion, the focal point of the sanctuary and Mysteries, was enlarged to be bigger than ever before. Fortunately, all sides during the Peloponnesian War respected the sanctity of Eleusis, and so it escaped harm during that bloody conflict.

Over time, the sanctuary of Eleusis came to be controlled by others than the Athenians – the Macedonians during the Hellenistic age, and the Romans during the Roman Empire when, during the reigns of Hadrian (A.D.117-138) and Marcus Aurelius (A.D. 161-180), there was a final flurry of activity. The sanctuary achieved its greatest extent with the addition of triumphal arches, large and small propylaea, and a Roman court.

Also, Roman citizens were then permitted to be initiated into the Mysteries.

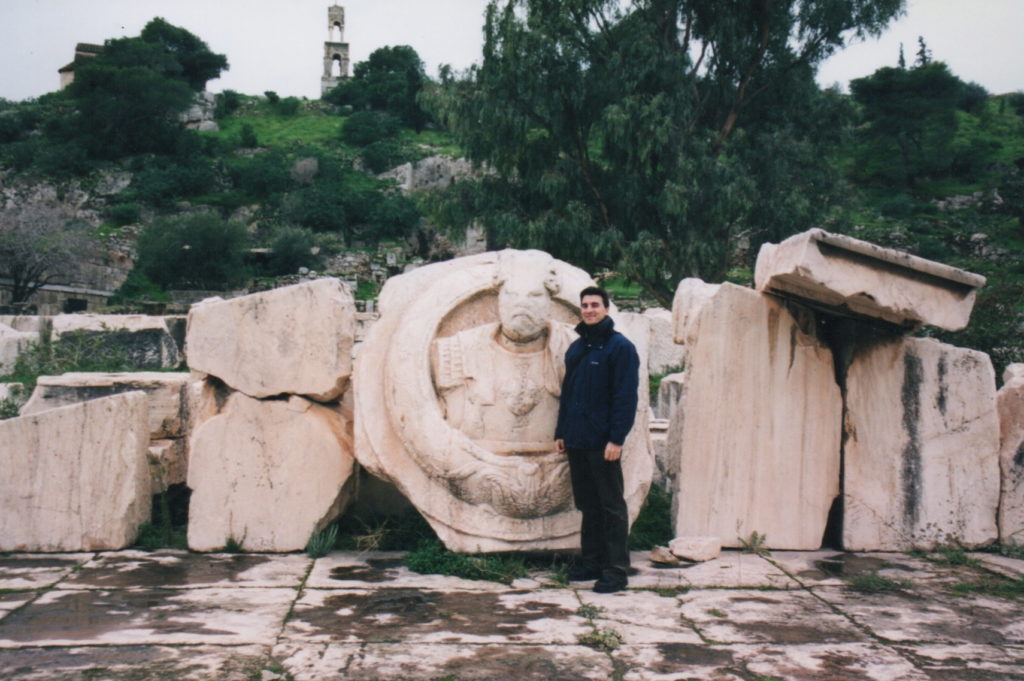

Adam standing in front of one of the Roman pediments portraying Marcus Aurelius or Hadrian in the Roman Court of Eleusis.

The end of the Eleusinian Mysteries began with the Theodosian decrees in around A.D. 350 when the ancient cults were forbidden in favour of Christianity, and then in A.D. 395 Alaric and his Visigoths destroyed the sanctuary once and for all.

The cult of Demeter faded away…

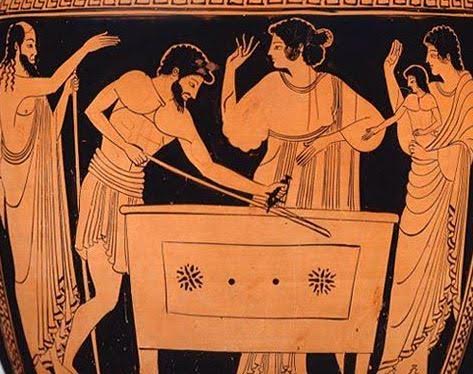

Now when all-seeing Zeus the loud-thunderer heard this, he sent the Slayer of Argus whose wand is of gold to Erebus, so that having won over Hades with soft words, he might lead forth chaste Persephone to the light from the misty gloom to join the gods, and that her mother might see her with her eyes and cease from her anger. And Hermes obeyed, and leaving the house of Olympus, straightway sprang down with speed to the hidden places of the earth. And he found the lord Hades in his house seated upon a couch, and his shy mate with him, much reluctant, because she yearned for her mother. But she was afar off, brooding on her fell design because of the deeds of the blessed gods. And the strong Slayer of Argus drew near and said:

“Dark-haired Hades, ruler over the departed, father Zeus bids me bring noble Persephone forth from Erebus unto the gods, that her mother may see her with her eyes and cease from her dread anger with the immortals; for now she plans an awful deed, to destroy the weakly tribes of earthborn men by keeping seed hidden beneath the earth, and so she makes an end of the honours of the undying gods. For she keeps fearful anger and does not consort with the gods, but sits aloof in her fragrant temple, dwelling in the rocky hold of Eleusis.”

So he said. And Aidoneus, ruler over the dead, smiled grimly and obeyed the behest of Zeus the king. For he straightway urged wise Persephone, saying: “Go now, Persephone, to your dark-robed mother, go, and feel kindly in your heart towards me: be not so exceedingly cast down; for I shall be no unfitting husband for you among the deathless gods, that am own brother to father Zeus. And while you are here, you shall rule all that lives and moves and shall have the greatest rights among the deathless gods: those who defraud you and do not appease your power with offerings, reverently performing rites and paying fit gifts, shall be punished for evermore. (The Hymn to Demeter)

If I remember correctly, we entered the sanctuary from the area known as the Roman Court, there to be greeted by the face of a Roman emperor on a pediment, possibly Marcus Aurelius or Hadrian.

Upon entering, the sight that meets you is one of ruin, especially if it is a cloudy, cold day. I know that when I stepped onto the site of the sanctuary, I felt a great sadness. And it’s no wonder, considering the story behind it all, and why Eleusis was such a sacred place to the ancient Greeks and Romans.

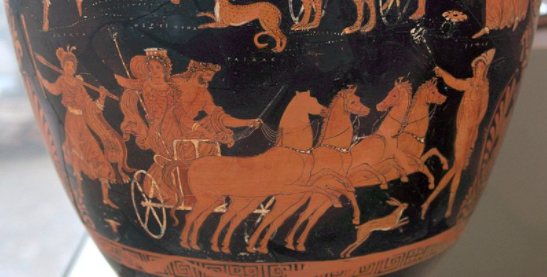

Persephone was filled with joy and hastily sprang up for gladness. But he on his part secretly gave her sweet pomegranate seed to eat, taking care for himself that she might not remain continually with grave, dark-robed Demeter. Then Aidoneus the Ruler of Many openly got ready his deathless horses beneath the golden chariot. And she mounted on the chariot, and the strong Slayer of Argos took reins and whip in his dear hands and drove forth from the hall, the horses speeding readily. Swiftly they traversed their long course, and neither the sea nor river-waters nor grassy glens nor mountain-peaks checked the career of the immortal horses, but they clave the deep air above them as they went. And Hermes brought them to the place where rich-crowned Demeter was staying and checked them before her fragrant temple.(The Hymn to Demeter)

It is indeed a strange thing to come to a place where the myths come alive, where the air still rings with weeping and the chants of thousands of initiates whose thoughts were bent upon that same sad story across the ages.

As I walked through the greater and lesser propylaeafarther into the sanctuary, on my right there appeared a dark, hollowed out rock face.

This was the area of the Ploutoneion, and there, at the base of the rock, the gateway to Hades itself.

But the sad thing was the small round well before it where Demeter is said to have knelt down and wept for her daughter.

To me, this was the most moving part of the sanctuary of Eleusis. It is a place of mourning and regret, a sort of ancient crime scene.

And when Demeter saw them, she rushed forth as does a Maenad down some thick-wooded mountain, while Persephone on the other side, when she saw her mother’s sweet eyes, left the chariot and horses, and leaped down to run to her, and falling upon her neck, embraced her. But while Demeter was still holding her dear child in her arms, her heart suddenly misgave her for some snare, so that she feared greatly and ceased fondling her daughter and asked of her at once: “My child, tell me, surely you have not tasted any food while you were below? Speak out and hide nothing, but let us both know. For if you have not, you shall come back from loathly Hades and live with me and your father, the dark-clouded Son of Cronos and be honoured by all the deathless gods; but if you have tasted food, you must go back again beneath the secret places of the earth, there to dwell a third part of the seasons every year: yet for the two parts you shall be with me and the other deathless gods. But when the earth shall bloom with the fragrant flowers of spring in every kind, then from the realm of darkness and gloom thou shalt come up once more to be a wonder for gods and mortal men.(The Hymn to Demeter)

What were the Eleusinian Mysteries all about? What was involved?

The truth is, we don’t actually know much at all. That is the nature of ancient mystery religions. The initiates had to be chosen and then they underwent instruction, but they were sworn to absolute secrecy about what occurred inside the sanctuary and the rites that took place in the Telesterion, the focal point of the Mysteries themselves.

What we do know today is solely based on the public rituals of the festival.

We know that the Mysteries were celebrated twice a year, in the Spring and in the Autumn. The ‘Lesser Mysteries’ were celebrated near Athens in the Spring in the month of Anthesterion (March), and the ‘Greater Mysteries’ were celebrated in the Autumn in the month of Boedromion (September).

Here is what we know was involved…

The Greater Mysteries, over several days, involved making sacrifices, and a procession with the priestess of Demeter carrying the sacred cymbals all the way from Eleusis to Athens.

An official proclamation, or prorrhesis, of the opening of the festivities followed the procession. Anyone who was guilty of murder, desecration, or who spoke no Greek was excluded from the festivities.

Initiates of the Eleusinian Mysteries went through a ceremony of purification in the sea at Phaleron (modern Faliro in Athens), and sacrificed piglets. More sacrifices followed and then there was the great procession of initiates from Athens to Eleusis along the Sacred Way with stops at altars and shrines along the journey, more sacrifices and the chanting of hymns.

Model of the Sanctuary of Eleusis with the Ploutoneion in the centre and the large Telesterion top left