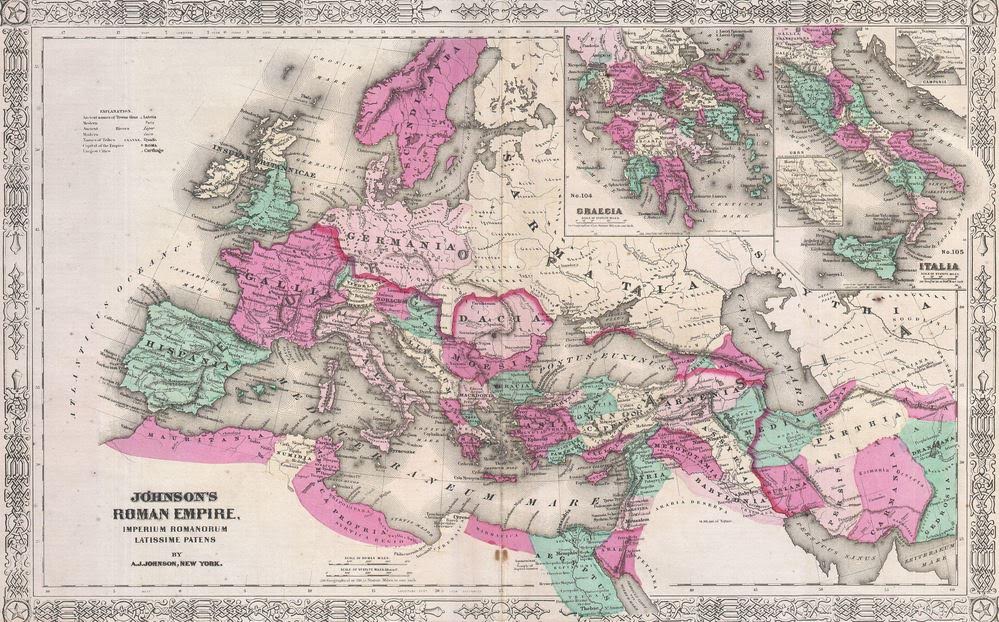

Part I – The Roman Empire in A.D 197

In this short blog series, I’m going to look at the world in which A Dragon among the Eagles takes place, the Empire itself, the state of the army, Rome’s primary enemies, and the many places of the Middle East where most of the action takes place.

In Part I, we’re setting the scene with a look at the state of the Roman Empire in the year A.D. 197 when this story begins…

The Roman Empire had reached a critical time in its history at the end of the second century A.D., but, despite this, it is a period for which we have very few primary sources.

It is also a period that is often glossed over in fiction and non-fiction today.

That is one of the things that drew me to write the Eagles and Dragons series, that there was/is so little about this supremely fascinating period in the history of the Roman Empire, its people, its geography, and the workings of the great machine that kept it all going, part of which was the army.

A Dragon among the Eagles is the prequel novel to Children of Apollo. It is concerned mainly with the early days of Lucius Metellus Anguis’ enlistment in the imperial legions and his march east in one of the largest invasion forces Rome has ever assembled.

As we know, politics in ancient Rome governed all, and so before we set out on the march, we need to develop a picture of what the Empire looked like in A.D. 197.

Emperor Septimius Severus

Septimius Severus is emperor in the year 197, but he actually came to power in A.D. 193. What he established was a huge military dictatorship, but this in fact provided some much-needed stability after the chaos of Commodus’ reign, and the subsequent murder of his successor, Pertinax, by the corrupt Praetorian Guard, after only three months. The Praetorians then auctioned off the imperial throne to the highest bidder, the rich senator Didius Julianus. The latter ruled for just about sixty-six days.

It was at this time, upon the murder of Pertinax in A.D. 193, that Septimius Severus’ troops proclaimed him emperor. He marched on Rome with his legions and promptly discharged the corrupt Praetorian Guard, banishing them from Rome, on pain of death.

Severus then re-appointed his own, fiercely loyal men of the Danubian legions to the Praetorian Guard. He was quick to consolidate power, but things were not yet meant to go smoothly.

Like any good bit of Roman history, civil war ensued.

Two other claimants to the imperial throne came forward with the support of their troops: Clodius Albinus, Governor of Britannia, and Pescenius Niger whose legions were in Syria.

After a few years of bloody fighting on two fronts, Septimius Severus became the sole emperor of the Roman Empire with his victory over Clodius Albinus at the Battle of Lugdunum in Gaul, early in 197.

Marching Legions (Wikimedia Commons)

After many years of turmoil around the imperial throne, the Empire finally had a strong ruler. But this was now an age for the military, and Severus knew how to treat his troops, granting them pay raises, the right to marry, and much more that made him popular.

However, he was not so popular with the Senate because of his use of the military to seize power. Severus was not to be cowed. He held a series of proscriptions to eliminate those senators who had supported his rivals in the civil war, replacing them with men loyal to him.

Severus was now firmly, and safely, on the imperial throne, set to be the most stable emperor since Marcus Aurelius.

This is also an interesting period in history for the role of women, thanks to Severus’ empress, Julia Domna.

Empress Julia Domna was the first of the ‘Syrian Women’ of the Severan dynasty, and the sources, such as Cassius Dio, seem to suggest that she had an almost equal share in power and decision-making alongside her husband. They were the ultimate power couple.

Empress Julia Domna

Julia Domna was said to be highly intelligent, and politically astute. She had a circle of intellectuals from around the world, including philosophers, scientists, and priests who came to talk with her and exchange ideas. It was a sort of ancient Roman salon of great thinkers.

Like all Roman military leaders, Septimius Severus needed a campaign to solidify his claims and busy his troops. Another war against fellow Romans would not do.

So, in A.D. 197, the campaign against Rome’s long-time enemy, Parthia, was set to begin.

We’ll discuss the Parthians in a separate post.

It is important to note however, that in the past many Romans had taken on Parthia and failed. Could Septimius Severus be the one to finally bring the Parthians to their knees?

This is the world in which A Dragon among the Eagles takes place.

A strong emperor is finally in power again. He has numerous loyal legions, and has consolidated his power. He has the love of the Roman people and the troops, if not that of the Senate. And he and his men are itching for a titanic fight.

Part II – The Imperial Roman Legion

The world in which A Dragon among the Eagles takes place, and with which the main characters are concerned, is also the world of the Roman legion.

Indeed, the imperial Roman legion figures largely in the entire Eagles and Dragon series, and so, I thought it good to do a brief introduction of the make-up of the legion at the time the book begins in A.D. 197.

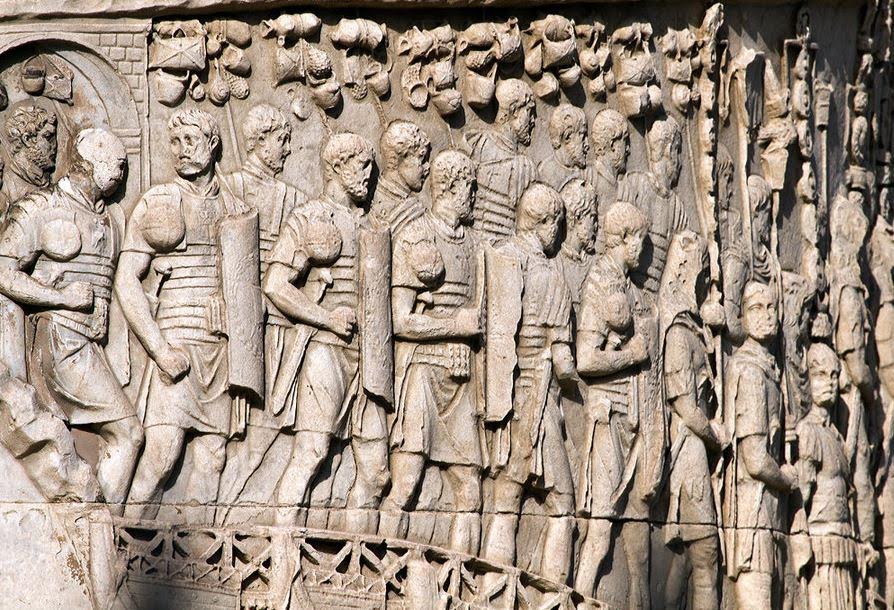

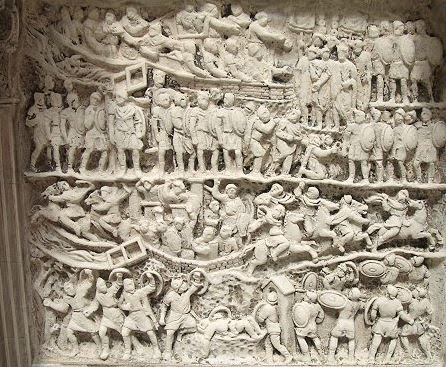

Roman legionaries on Trajan’s column

At this time in the history of the Roman Empire, the Roman legion is a well-oiled machine. It, and its troops, had been perfected after centuries of warfare, of trial and error, victory and defeat.

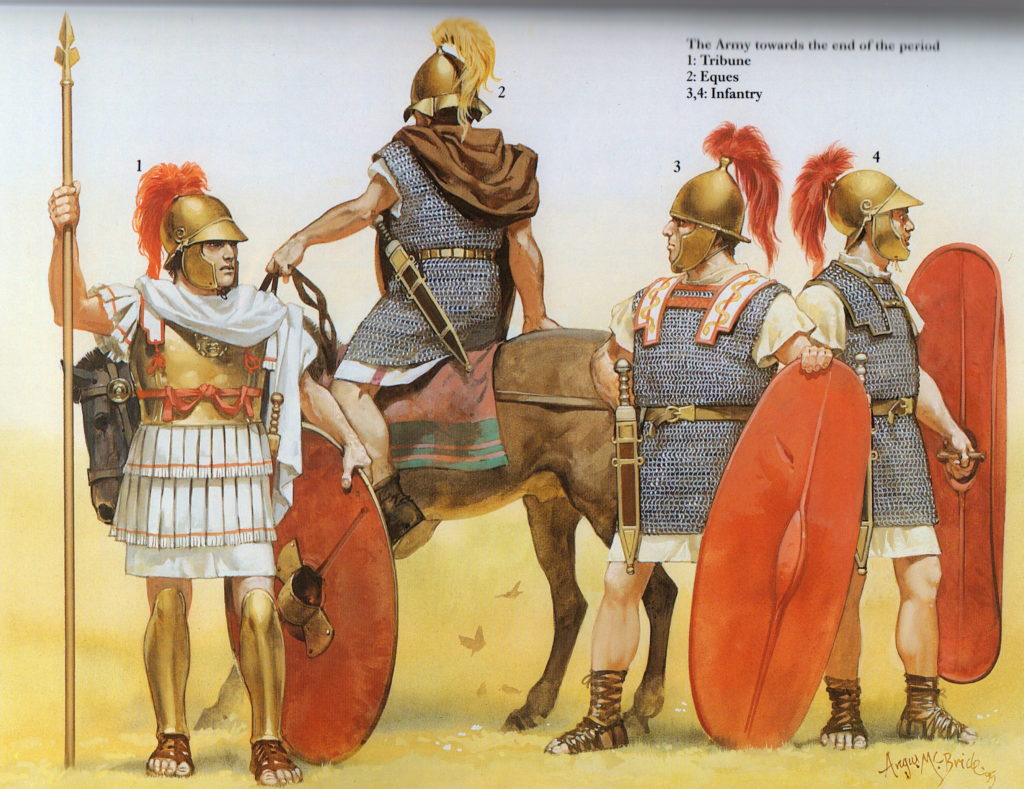

This army, the army of the Principate, is quite different from that of the Republic. It used to be that Roman legionaries were required to meet minimum requirements of possession and wealth in order to qualify for service in the ranks.

Republican Roman troops (illustration by Angus McBride)

This all changed in 107 B.C when Caius Marius was elected consul and sent to Numidia to continue the war there. However, Marius was denied the right to raise new legions in Africa, permitted only to take volunteers with him.

Of course, Marius took advantage of this, and in a move no other had taken, he appealed to the poorest classes of citizens who became known as the capite censi.

These ‘head count’ citizens were enthusiastic about joining the legions and the new opportunity for a livelihood that it presented them with. They became the backbone of the Roman Legion, and from that time onward the link between military service and property was done away with. They need only have been citizens.

Gaius Marius among the ruins of Carthage (Joseph Verner 18th century)

Marius made many reforms to the Roman army which I won’t go into here, however, his move contributed to the creation of a permanent, full-time citizen army, a self-sufficient fighting force of well-trained men with standard-issue equipment, food and lodging. They carried everything they needed on the march on their own backs, including weapons, spikes for palisades, pots, pans, and pick-axes for digging fortifications.

Marius’ Mules – Re-enactors marching in full kit

Because of all the kit they carried in the field, they became known as ‘Marius’ Mules’.

The average kit for a rank-and-file soldier in the imperial legions included hobnail sandals known as caligae, a standard tunic, a leather belt or cingulum, a lorica segmentata which was a breast plate made up of individual iron strips, a helmet, cloak, gladius (short sword), pugio (dagger), a pilum (javelin), and a scutum (shield).

Re-enactor in Roman Legionary outfit

In A Dragon among the Eagles, there is mention of the various ranks and units that make up the legion, so I think it a good idea to cover the basics now.

The smallest unit of men in the imperial legion was a contubernium which consisted of eight men who shared a tent, or barrack room. These men marched, fought, lived, and cooked together.

Then there was the century. This is probably the most well-known unit of men. It consisted of 10 contubernia, and was run by a centurion with a standard bearer and an optio beneath him.

The centurion was usually a career soldier, and a harsh task-master. He wore different armour that was chain mail, usually with a harness decorated with phalerae, decorative discs that represented awards he had been given. The crest of a centurion’s helmet was horizontal, and he carried a short wooden staff called a vinerod, which gave him the right to strike his citizen soldiers in the interests of discipline.

Re-enactor dressed as a Centurion (Wikimedia Commons)

There are stories about a particular centurion in the imperial legions whose nick-name was ‘give me another’ because he was constantly breaking his vinerod over the backs of his men!

Centuries of eighty men were the most flexible military units in the legion. They numbered enough to go on patrol, or building duty, and could manoeuvre effectively in battle.

Now, the next unit of the legion was the cohort.

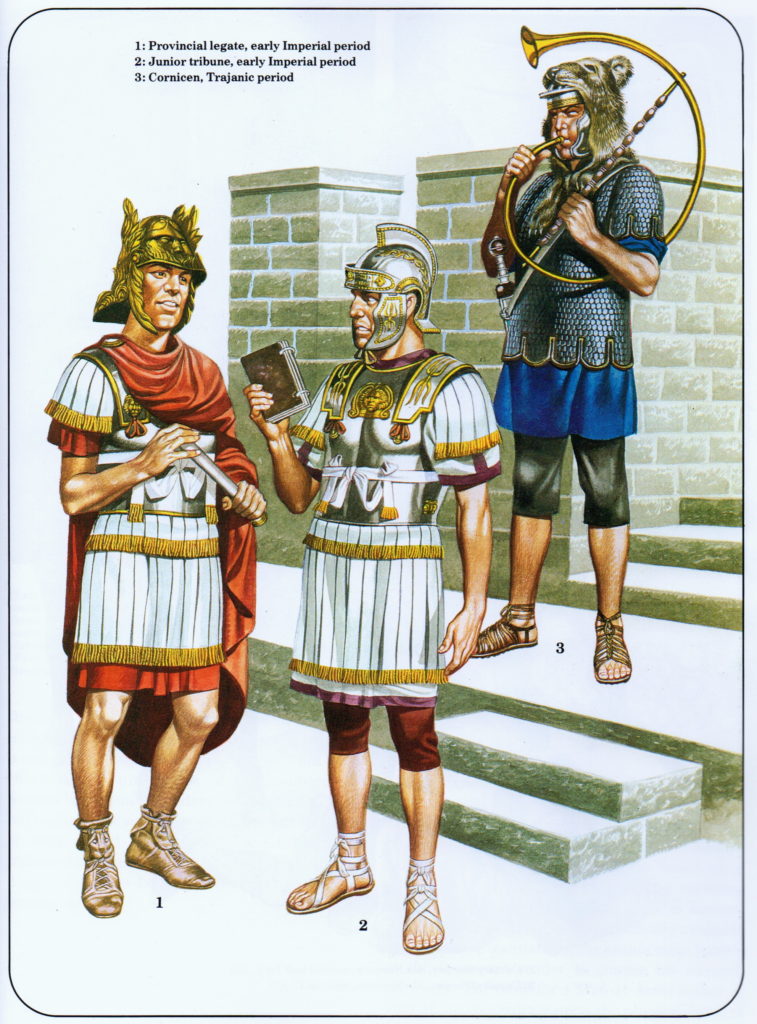

The imperial cohort was made up of 480 men, and consisted of six centuries let by an Equestrian tribune. The first cohort of a legion, however, was led by a Patrician tribune.

Officers of the Imperial Roman Legions (illustration by Ron Embleton)

Finally, there were ten cohorts in a legion which brought the average number of troops in the imperial legion to 5000.

The commander or general of an entire legion was known as the legatus legionis, or legate commander. This person was usually a senator, just like the patrician tribune who was his second-in-command. The third person of overall authority in the legion was the camp prefect, or praefectus castrorum. The latter was often a career soldier, perhaps a former centurion who had been promoted, and was responsible for much of the legion’s administration and logistics.

There were many other minor positions within the legions such as duplicarii, men who received double pay for skills such as engineering, or the building of siege equipment, as well as benificari, those who were aides to the legate or other officers, and who were excused for intense labour such as the digging of ditches and erecting palisades.

Roman legionary standards with an image of Emperor Severus and his family

We must not forget the standard bearers who made up the imperial legion. These included the vexillarius, the person who carried the vexillum standard of each unit, the signifer, the soldier who carried a century’s standard and wore a wolf or other pelt over his helmet. There was the cornicen, the trooper who carried the cornu, the round horn used to rally the troops and give commands, as well as the imaginifer of the legion, the trooper whose task it was to carry the image of the emperor before the legion.

Probably the most important standard bearer was the aquilifer, the man whose solemn duty it was to carry the legion’s golden eagle, the aquila, into battle. This man was to protect the legion’s eagle at all cost, for it was the ultimate disgrace for a legion to lose its aquila to an enemy.

Re-enactor dressed as an Aquilifer

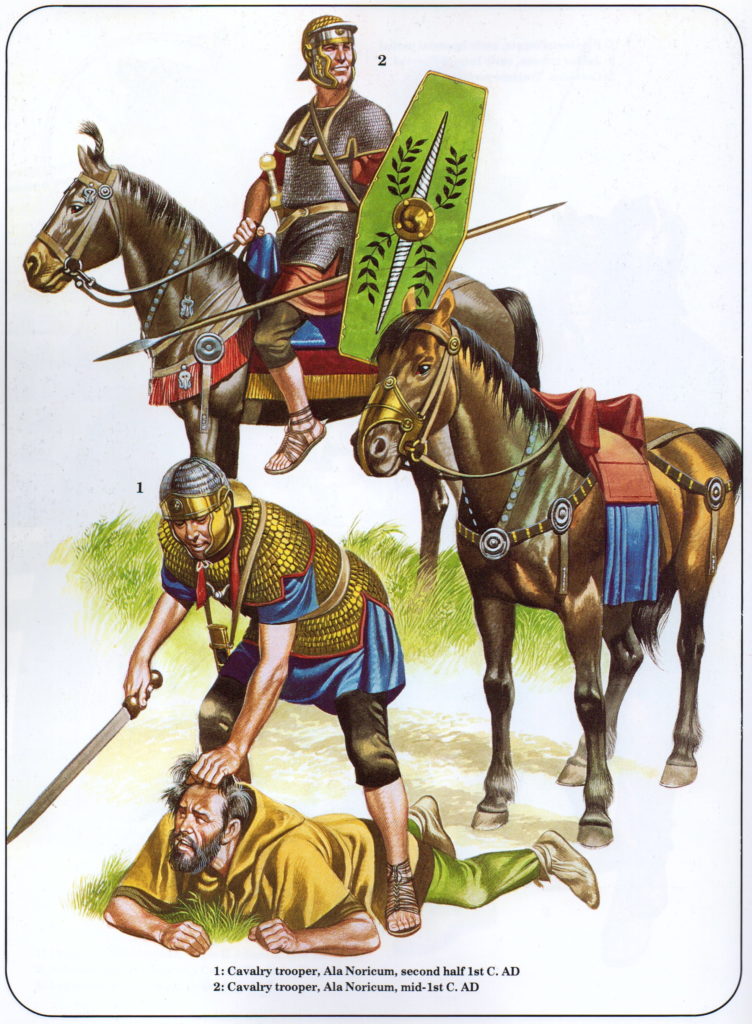

Along with the 5000 regular troops that made up an imperial legion, there were often alae, or auxiliary units, attached to the legion. These were usually units of 120 cavalrymen who acted as scouts and supported the legion on the march. They were often made up of foreign troops who had been brought into the Roman ranks such as Sarmatians, Numidians, or Scythians to name a few.

Ala units might also consist of skirmishers such as Cretan or Balearic slingers, but most often they were cavalry.

Auxiliary Cavalry troops (illustration by Ron Embleton)

The imperial Roman legion was one of the most effective fighting units of the ancient world, and it is no wonder that the Empire covered so much of the known world by the time in which A Dragon among the Eagles takes place.

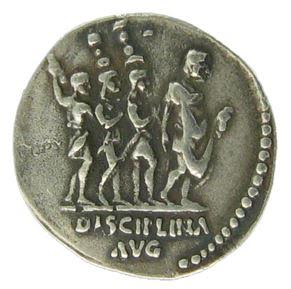

Disciplina, the goddess personification of discipline, was something that was taken very seriously. If a soldier obeyed her and remembered his training, he would survive the direst of circumstances.

Roman coin showing stardard bearers and the world ‘Disciplina’ – second century A.D.

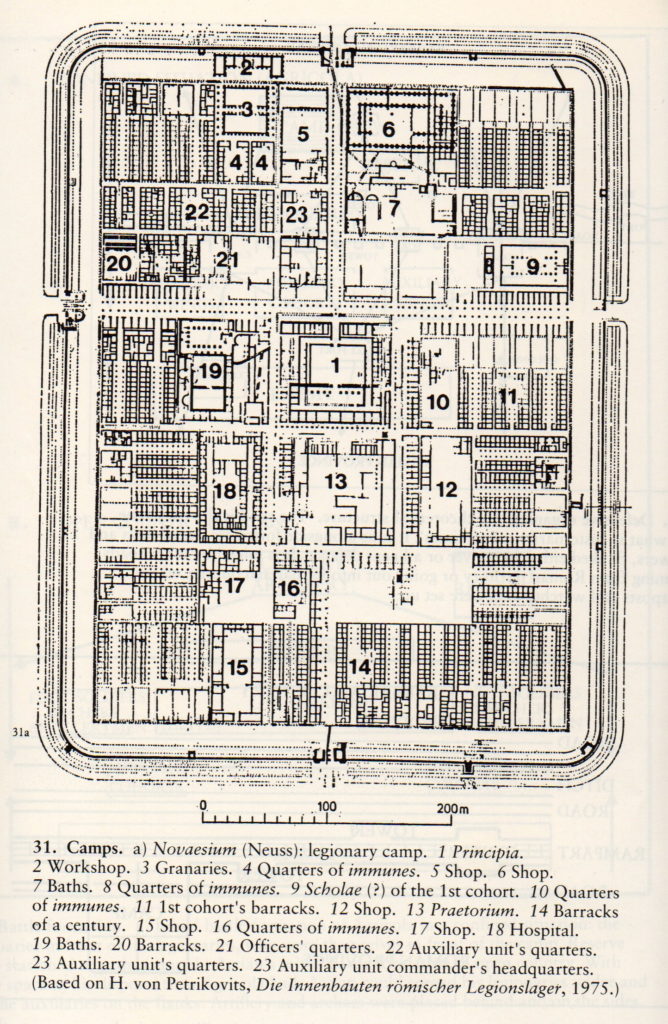

When the legions marched in the field, every night they dug in, every trooper going to his assigned space to dig ditches, pile up ramparts, and raise the palisade around the entire camp.

Tent and command centre, the Principia and Praetorium, tribunes’ tents, stables etc. were always in the same position, the streets set out in the same grid every time. So, whatever happened, a Roman soldier knew where he was, and what he had to do.

Every morning, when they would break camp, they would take down the work of the previous evening, which they had done after a twenty mile march, so that the enemy could not make use of their fortifications.

Plan of a typical legionary fortress (FromThe Imperial Roman Army by Yann Le Bohec)

It was hard work, but the imperial legion gave opportunity to the poorer classes of Roman citizens and allowed them to make something of themselves, if not at least be clothed and fed at the state’s expense.

In return, the men of the legions bled for Rome as they extended her borders into the world.

A Dragon among the Eagles takes place during the Severan invasion of the Parthian Empire, one of the biggest thorns in Rome’s side for over two hundred years.

In A.D. 197, Septimius Severus set out with one of the largest invasion forces in Rome’s history, made up of a titanic 33 legions.

The stage was set for one of the greatest military campaigns in Rome’s history.

In the next post, we’ll look at this powerful enemy and the tactics they used in battle against the legions.

Until then, check out this great video that illustrates the make-up of the Roman legion.

Thank you for reading!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wCBNxJYvNsY

Part III – Rome’s Enemies: The Parthian Empire

The setting for A Dragon among the Eagles is the Severan invasion of the Parthian Empire, an enemy that had harassed Rome for over two hundred years, and had dealt the legions one of Rome’s biggest defeats at the battle of Carrhae in 53 B.C.

But who were the Parthians?

Some believe they were successors to the Persians, but that is not entirely true. The truth is that the Parthians were a sort of amalgam of peoples and cultures.

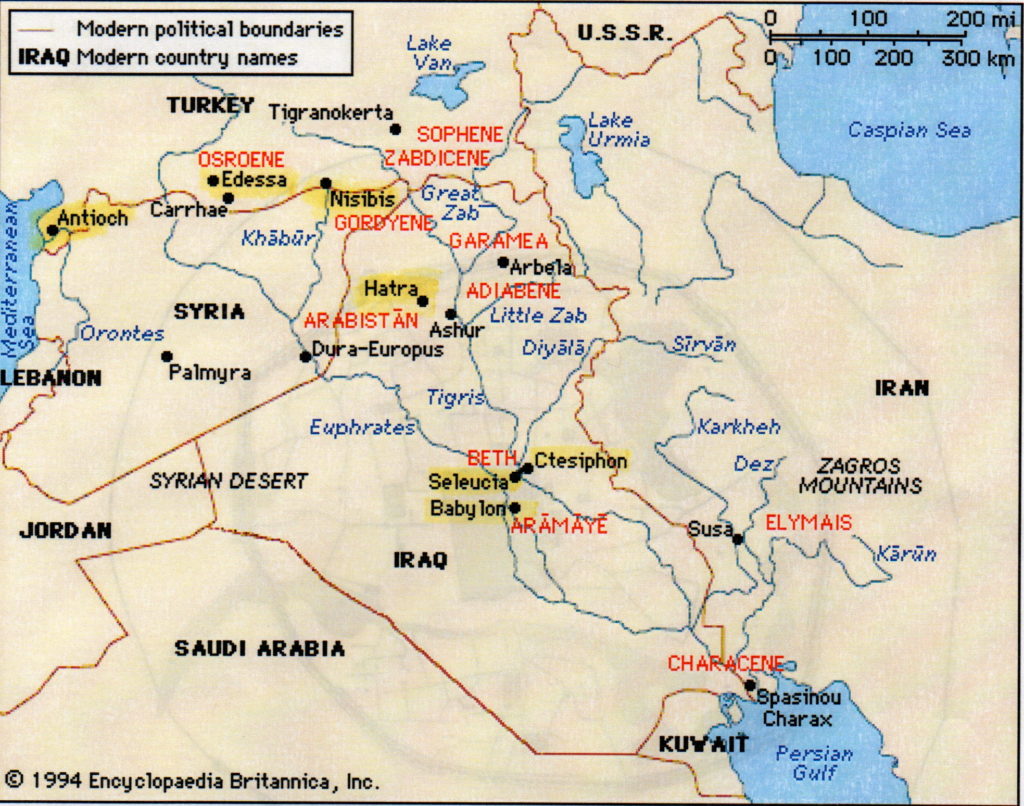

The region ruled by the Parthian Empire included modern Iraq and Iran. It was established when Arsaces I rebelled in the North against the Seleucid Empire (named after Alexander the Great’s general, Seleucus) in the mid-third century B.C.

Parthian Empire (Wikimedia Commons)

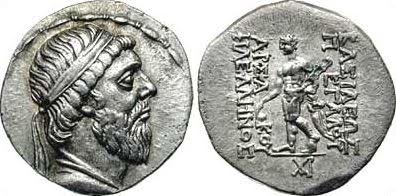

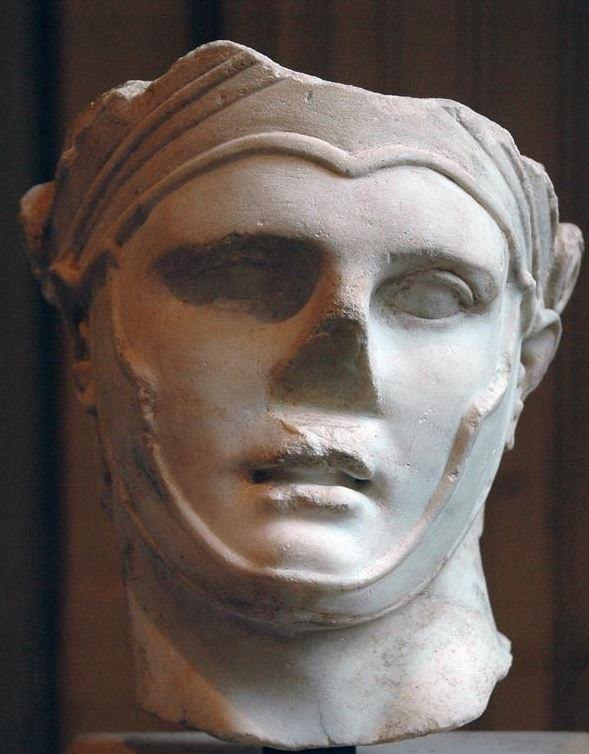

Then, in the mid-second century B.C. Mithridates I of Parthia expanded the empire by taking Media and Mesopotamia from the Seleucids, making the Parthian Empire the region’s power-house.

At its greatest extent, the Parthian Empire stretched from the northern Euphrates and what is now central Turkey, to eastern Iran. Included in this vast territory was an enormous stretch of the Silk Road which tied the Mediterranean world to the East and was the key to dominating trade.

Parthia was a real cultural mix, with the main elements being Persian and Hellenistic. The Parthians were philhellenes, a people who loved and adopted Greek culture, or at least much of it. The Parthian emperor carried the title of ‘King of Kings’, and there were some satraps beneath him, though most were vassal kings.

Mithridates I of Parthia, 171-139 B.C.

Like the Persians before them, the Parthians could call on vast numbers of soldiers, levied from different regions around the Empire.

As the Empire reached its peak power, a bigger power centre was needed, and so the capital was moved from Nisa to the place where things really come to a head in A Dragon among the Eagles: Ctesiphon.

I won’t go into a long discussion of the history of the Parthian Empire here, for our main concern is with their last great confrontation with Rome under the leadership of Septimius Severus.

However, apart from the wars with their regular enemies, the Seleucids, Scythians, and Armenians, it is important to highlight some of the ‘bad blood’ between Parthia and Rome. This will help us to understand Rome’s perspective perspective in A.D. 197 when the story begins.

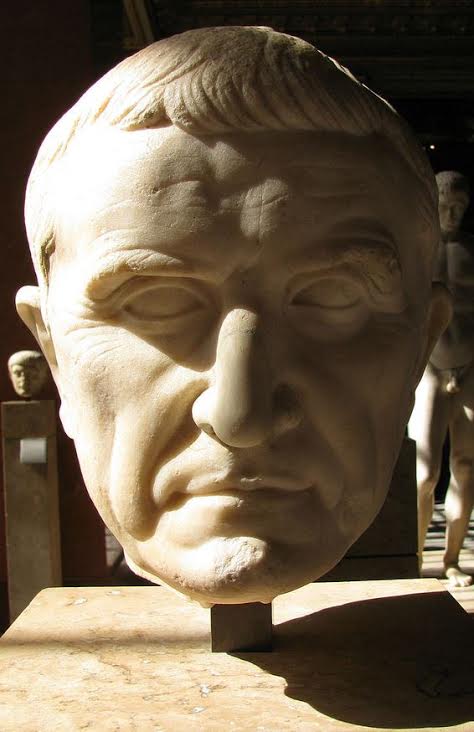

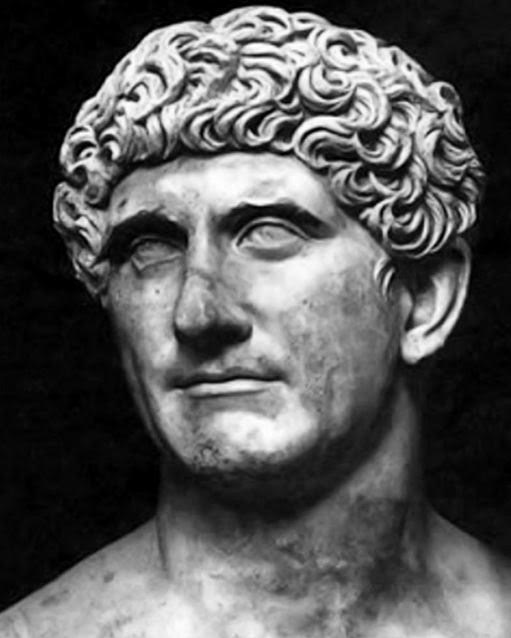

Marcus Licinius Crassus

In the late first century B.C. the Roman Republic came into conflict with Parthia over the client-kingship of the Armenians. Hostilities began, and so Rome sent the triumvir, Marcus Licinius Crassus to Parthia with a force of seven legions plus auxiliaries.

Some of you may recognize the name of Crassus from the history, movies, and books about Spartacus. This is the same Crassus, the rich man of Rome.

Crassus went confidently to war with the Parthians, but in 53 B.C. his forces were crushed by the smaller Parthian forces at the battle of Carrhae. To make matters worse, the legions’ aquilae, the sacred golden eagles, and other standards were taken by the Parthians. This was the ultimate disgrace for a legion.

According to some sources, the Roman dead at Carrhae numbered twenty-thousand, with another ten thousand taken prisoner.

And Crassus? He was captured and killed. Some say that the Parthians did away with Crassus by pouring molten gold down his throat.

But Rome would not go away so easily.

Marcus Antonius

From 40-39 B.C. Mark Antony (Yes, that Mark Antony!) attacked Parthia and came away with some victories, but the gains of those victories proved difficult to hold. However, Rome now held Syria.

Then Augustus, the first official emperor of Rome, managed to negotiate the exchange of a Parthian prince Rome had captured for the legionary standards that had been lost at Carrhae, as well as the remaining Roman prisoners of war.

This was a big coup for Augustus, and an opportune moment for Rome, as the Parthian court was plagued by infighting that led to civil war.

Roman coin showing Parthian return of Roman Standards

An interesting aside is that at this time, the Han Dynasty of China was apparently interested in diplomatic relations with Rome in the hundred years or so after Augustus, but nothing came of it. It seems Rome was not the only power that felt the Parthians were a real thorn in their side.

Over the decades, there were various Roman-Parthian wars, interspersed with periods of peace. That is, until A.D. 114 when Emperor Trajan renewed hostilities and captured Nisibis, which was key to securing the route across the Mesopotamian plain.

Trajan, that warlike emperor, went on to invade Mesopotamia, capturing the fortress of Dura Europus, Seleucia, Susa, and the capital of Ctesiphon. Trajan also went up against the desert city of Hatra, but his siege failed, causing the emperor to retreat. He died before being able to return and finish the job.

Emperor Hadrian

When Emperor Hadrian (A.D. 117-138) came to power, he began shoring up the Empire’s borders from Hadrian’s Wall in the North, to the Euphrates in the East. There was a time of relative peace again, until Vologases of Parthia invaded Roman territory in Armenia and Syria, and took Odessa. Marcus Aurelius was emperor at this time, and with a new war underway with Parthia, his legions marched on and burned Seleucia and Ctesiphon before having to retreat due to an outbreak of plague in the ranks. Marcus Aurelius’ war with Parthia ended in A.D. 166.

Now we come to the period of the Severan invasion of Parthia against Vologases V. This is when A Dragon among the Eagles begins.

In the book, the Emperor is gathering his legions outside of Antioch, with some new legions being raised in Italy and Greece especially for the campaign. These new legions are the I, II, and III Parthica Legions, and this is where our protagonist, Lucius Metellus Anguis, gets his start.

Septimius Severus led an army of 33 legions into Parthia at this time, and one would think that he easily crushed the Parthians with such a large force. But that is not the case.

Severus’ Parthian campaign, while relatively short, was also a brutal one.

Roman Re-enactment group on the march!

After all the ill-will between Rome and Parthia, as outlined above, Severus wanted to be the one who crushed Parthia once and for all. He had just come out of the civil war as the victor, but a victory against an enemy of Rome was needed. And what better enemy than Parthia?

The legions marched into Mesopotamia and relieved Nisibis, which had been withstanding a siege by the Parthians, under the gallant leadership of General Laetus. With Nisibis back under control, the Romans then made their way south along the Euphrates and Tigris rivers to take Seleucia, Babylon, and finally the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon. It was a resounding, brutal and bloody success.

However, as with Trajan’s campaign against Parthia, Hatra withstood two major sieges in two years by Severus’ forces, and still the Romans could not take it.

We’ll look more closely at some of the locales of A Dragon among the Eagles in the next post of this blog series.

The question we should ask ourselves now is how were the Parthians able to withstand Rome for so long, and even deliver a crushing defeat such as at Carrhae, even when they had inferior numbers?

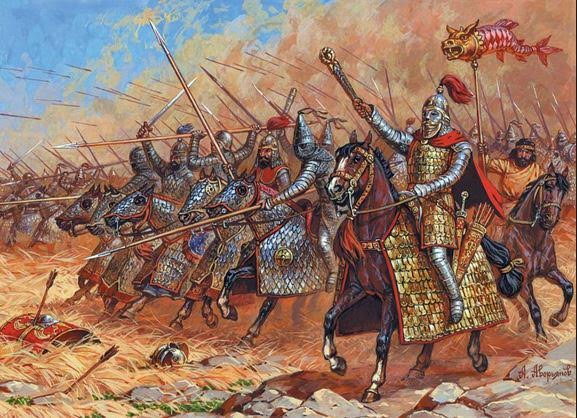

The answer? Cavalry.

The Parthians were expert horsemen in the field, so much so, that almost the entirety of their army was made up of cavalry and nothing else.

The Parthian Empire had no standing army, apart from the king’s guard, but they had a large population and many horses.

The two predominant types of cavalry were the light horse archers, and the heavy cataphracts, and the one-two punch of these two groups together proved more than a match for Rome’s legions for a long time.

Parthian Cavalry charge – artist impression

Parthian horse archers were good at harrying Roman troops by speeding toward the enemy in waves, unleashing a hail storm of arrows at full speed, and then quickly turning and fleeing before the Romans could pursue.

But these horse archers, even as they sped away, would continue to pommel their enemies with arrows facing backward in their saddles as they went. This is where the so-called ‘Parthian Shot’ comes from, an expression we use today for a verbal parting barb.

You can imagine that with their numbers, so many arrows could have the potential to throw any force into disarray. And these were the light cavalry, common class men wearing only a tunic and trousers, and carrying their short, composite bows and arrows. That’s it!

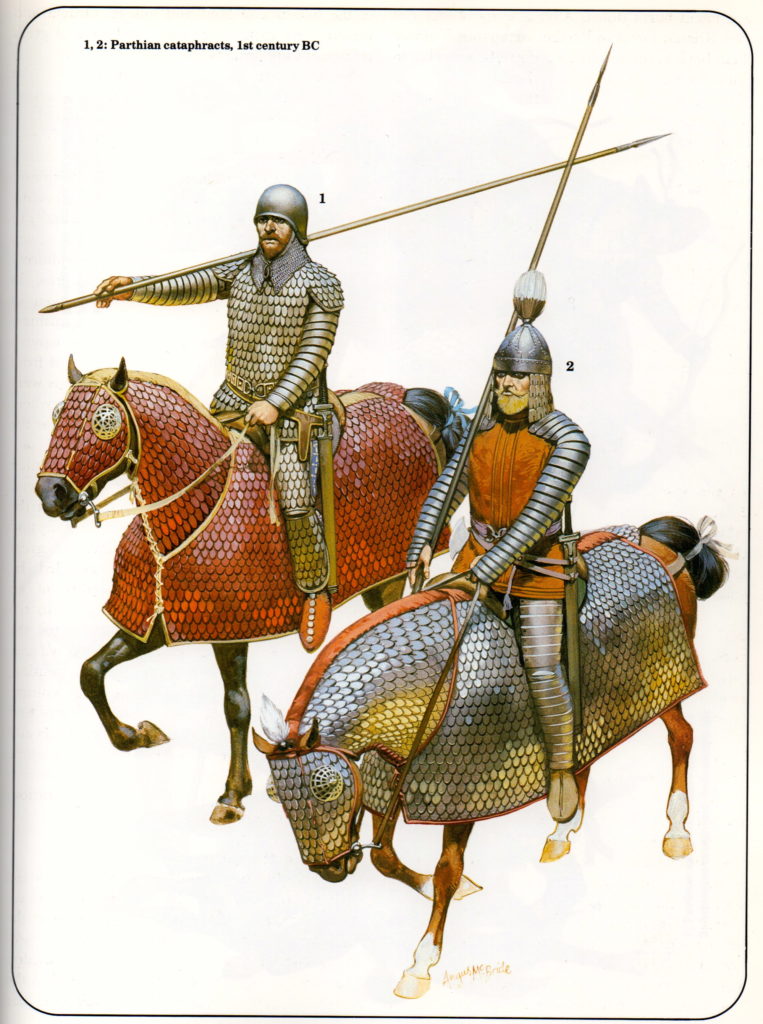

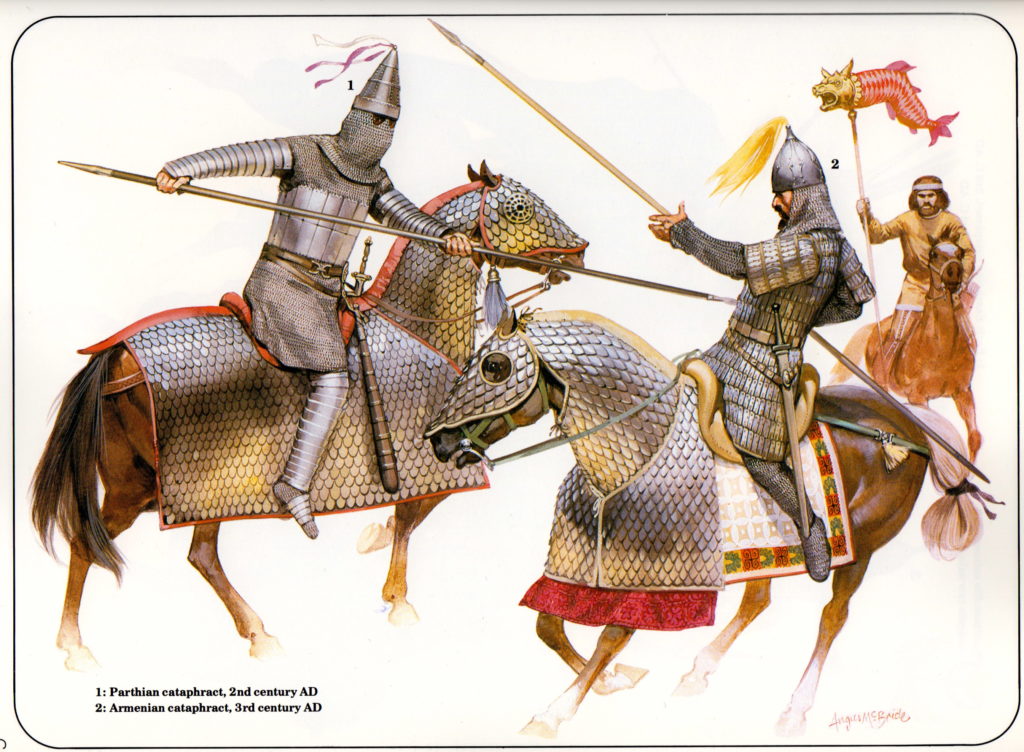

The real danger for the Romans, when fighting the Parthians, was the heavy cavalry, or cataphracts.

Parthian heavy cavalry (cataphracts) – illustrated by Angus McBride

The Parthian cataphract was one of the most terrifying horse warriors of the ancient world. Apart from having big horses, both man and horse were covered head to hoof in chain, scale, or plate armour, making them heavy and virtually impenetrable.

Their weapons were also something to be reckoned with. They carried things such as war-hammers with large spikes on the end, long maces and battle axes, and swords for slashing down from horseback.

But the scariest weapon wielded against the Romans by the Parthians was the kontos, or contus.

The kontos was a lance of about 4 meters long, or 12-14 feet. It was so long that the Parthian cataphract let go of his reins and used two hands to wield it.

With two hands on the kontos, these cataphracts were able to rip an enemy to shreds!

You can be sure that any Roman facing Parthians for the first time would have been ill-at-ease behind his scutum watching heavy Parthian cavalry bear down on the shield wall after a rain of arrows.

Parthian cataphract wielding the kontos (illustrated by Angus McBride)

The only thing that would have saved the Romans, and helped Severus’ forces to victory, were their superior numbers, and of course, discipline.

In A Dragon among the Eagles, we are put right in the midst of the chaos of war between Parthia and Rome, and let me tell you, writing about this campaign was not only fun, but also intense and nerve-wracking.

So, what eventually happened to the Parthians?

Well, the incessant civil strife at the imperial court, along with the war against Severus’ legions left them permanently weakened, even after rebounding from so many other conflicts with Rome.

Severus’ son, Caracalla came into conflict with Parthia in later years, but the once-great empire was already too weak, leaving the door open for yet another empire to step into the vacuum – the Sassanid Persians.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this brief post on the Parthian Empire.

Don’t forget, A Dragon among the Eagles is now out. Download your copy today!

Part IV – Cities under Siege

One of the great things about reading and writing historical fiction is that one is given the chance to journey to a time and place far away from the modern world.

In this fourth part of The World of A Dragon among the Eagles, we’re going on location to some of the places where the action takes place, some of which, sadly, are still making headlines today.

This won’t be an in-depth look at these ancient cities, for their histories are long and varied, and they each deserve their own a book. Here, we’re just going to take a brief look at their place in this story.

Sites where A Dragon among the Eagles takes place

The first third of A Dragon among the Eagles takes place in Rome, then Athens, and a little at Amphipolis which has gained recent fame for the massive tomb and the excavations there which have been linked to the period of Alexander the Great.

However, we are not going to look at Rome and Athens, as we visit those cities much more in Children of Apollo and Killing the Hydra, the sequels to A Dragon among the Eagles. If you would like to read more about Amphipolis, you can read this BLOG POST HERE.

For this blog, we are mainly concerned with the cities where Lucius Metellus Anguis, our protagonist, gets his first taste of war with the Legions.

Mesopotamia is said to be the cradle of civilization, a land of alternating fertility and desert where the first cities were built, and empires made. It also was, and is, a land of war, a land of terrible beauty.

Trooper in modern Iraq

For millennia, successive civilizations have fought over this rich land, a land from which Alexander the Great had decided to rule his massive empire.

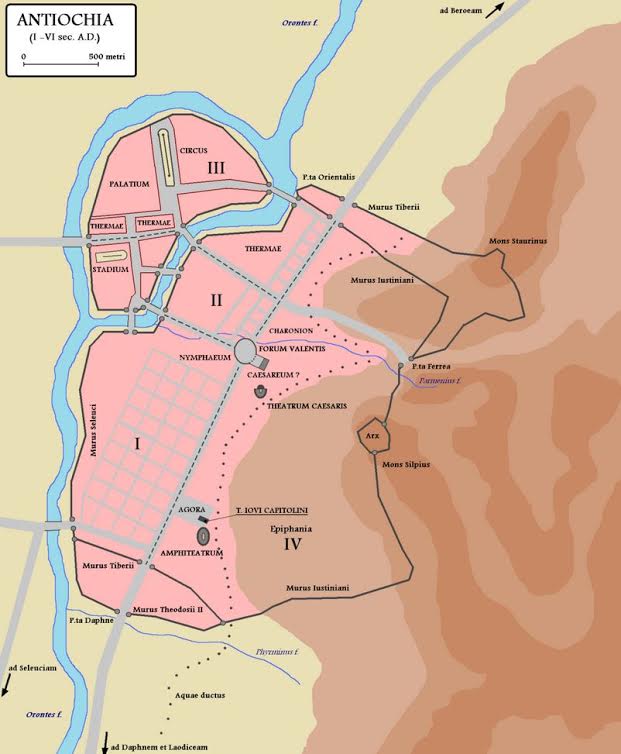

In A Dragon among the Eagles, Lucius Metellus Anguis’ legion arrives at the port of Antioch where Emperor Severus has assembled over thirty legions on the plains east of the city.

Antioch, which was then located in Syria, now lies in modern Turkey, near the city of Antyaka. It was founded in the fourth century B.C. by one of Alexander’s successor-generals, Seleucus I Nicator, the founder of the Seleucid Empire.

Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus named this city after his son, Antiochus, a name that would be taken by later kings of that dynasty.

Antioch was called the ‘Rome of the East’, and for good reason. It was rich, mostly due to its location along the Silk Road. Indeed, Antioch was a sort of gateway between the Mediterranean and the East, with many goods, especially spices, travelling through it. It is located on the Orontes river, and overlooked by Mt. Silpius.

In the book, we catch a glimpse of this Ancient Greek city that was greatly enhanced by the Romans who saw much value in it. Actually, most of the development in Antioch took place during the period of Roman occupation. Enhancements included aqueducts, numerous baths, stoas, palaces and gardens for visiting emperors, and perhaps most impressive of all, a hippodrome for chariot racing that was 490 meters long and based on the Circus Maximus in Rome.

Antioch, during the late second century A.D., rivalled both Rome and Alexandria. It was a place of luxury and civility that was in stark contrast to the world of war where the legions were headed.

Some ruins of Nisibis today

In writing A Dragon among the Eagles, I have followed the itinerary presented to us by Cassius Dio, the main source for this period in Rome’s history and the Severan dynasty. So, the order in which we are looking at these locales is roughly the order in which Severus’ legions are supposed to have attacked them.

The first real battle in the book, and the first time our main character experiences battle, is at the desert city of Nisibis.

At the time, Nisibis was under Roman control. However, that control was about to break according to Dio, as the Romans inside were just holding onto it. This is due mainly to the leadership of the Roman general, Maecius Laetus, whom we meet in the story.

Laetus managed to hold the defences of Nisibis until Severus’ legions showed up, and was hailed as a hero for it.

Nisibin Bridge – Gertrude Bell’s caravan crossing bridge.

Nisibis was situated along the road from Assyria to Syria, and was always an important centre for trade. This was the only spot where travellers could cross the river Mygdonius, which means ‘fruit river’ in Aramaic. Today it is located on the edge of modern Turkey.

Early in its history, Nisibis was an Aramaen settlement, then part of the Assyrian Empire, before coming under the control of the Babylonians. In 332 B.C. Alexander the Great, and then throughout the Roman-Parthian wars, it was captured and re-captured, over and over.

Such is the fate of strategically placed settlements, especially when they are located along the Silk Road.

Ruins of Edessa

From the bloody fighting in Nisibis, Severus’ forces then moved into the Kingdom of Osrhoene and the upper Mesopotamian city of Edessa, located in modern Turkey.

Edessa was originally an ancient Assyrian city that was later built up by the Seleucids.

Edessa’s independence came to an end in the 160s A.D. when Marcus Aurelius’ co-emperor, Lucius Verus, occupied northern Mesopotamia during one of the Roman-Parthian wars.

From that point on, Osrhoene was forced to remain loyal to Rome, but things changed when the civil war broke out between Severus, Pescennius Niger, and Clodius Albinus. Osrhoene threw their support behind Niger, who was then governor of Syria.

When Severus came out the victor in the civil war, it was inevitable that Edessa and Osrhoene would have to face the drums of war.

Edessa was where King Abgar of Osrhoene, who was sympathetic to the Parthians, was holed up as Severus’ legions advanced.

King Abgar of Osrhoene and Commodus

One has to wonder what King Abgar was thinking as Severus approached this ancient city. Whatever it was, and whatever he said to the Roman Emperor when he arrived, it must have been acceptable, for Abgar was permitted to keep his throne as a client king of the Empire.

There was a siege, but it seems that with King Abgar accepting Rome’s overlordship, and Severus’ need to move south, this is why the Osrhoenes escaped any large scale retribution.

In a way, it was not so for Lucius Metellus Anguis, for whom Edessa proves to be a harsh and enlightening experience.

At this time, Septimius Severus had his sights set on southern Mesopotamia and the great cities of Seleucia, Babylon, and the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon.

Ancient Babylon

The legions made their way south, directly for Seleucia-on-Tigris.

Seleucia, as the name suggests, was built by the Seleucus I Nicator in 305 B.C. as the capital of his empire. It was located sixty kilometers north of Babylon, and just across the Tigris River, on the west bank, from Ctesiphon. Today, Seleucia is located in modern Iraq, thirty kilometers south of Baghdad, and in its day, it was a major city in Mesopotamia.

It was a great Hellenistic city in the third and second centuries B.C., with a rich mixture of Greco-Mesopotamian architecture, and walls enclosing a full 1,400 acres as well as a population of 60,000 people.

When the Parthians took Seleucia, the capital was moved across the river to Ctesiphon and, though the city remained in use and inhabited, it went into a slow decline.

During the Roman-Parthian wars, Seleucia was burned by Trajan, rebuilt by Hadrian, and then destroyed again. Like a battered boxer with heart, it kept rising from the ground until there was no more will to keep it alive.

By the time Severus’ legions were marching on Seleucia, the Parthians had abandoned it completely, giving the Romans a foothold on the Tigris River, opposite their capital.

Seleucia on Tigris c.1927

Ctesiphon would have to wait, however, for there was another magnificent and symbolic prize within Severus’ grasp at that time – Babylon.

Alexander entering Babylon (Charles Le Brun)

I find that when I utter the name of Babylon, I get chills. Think about it, this is one of the most famous of ancient cities! This was the place that welcomed Alexander the Great with open arms and triumph, the place from which he had decided to rule his titanic empire, and the place where he died.

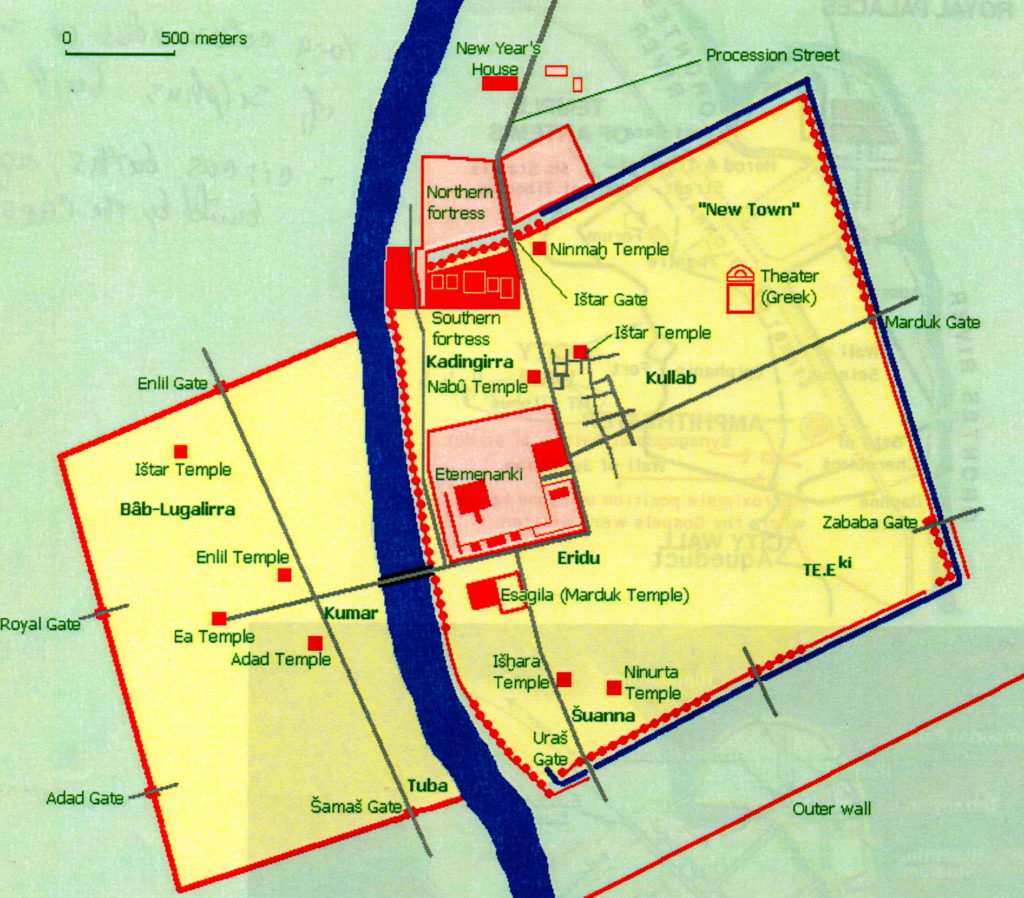

Babylon was located on the fertile plain between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Actually, part of it was built over the Euphrates.

The original settlement of Babylon is said to date to about 2300 B.C when it was part of the Semitic Akkadian Empire. It was fought over and rebuilt, and in about 1830 B.C. it became the seat of the first Babylonian dynasty.

From about 1770 B.C. to 1670 B.C. Babylon was the largest city in the world with a population of over 200,000.

Perhaps the most famous period in Babylon’s long and ancient history is during what is known as the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626-539 B.C.), and especially the reign of King Nebuchadnezzar II (605-562 B.C.)

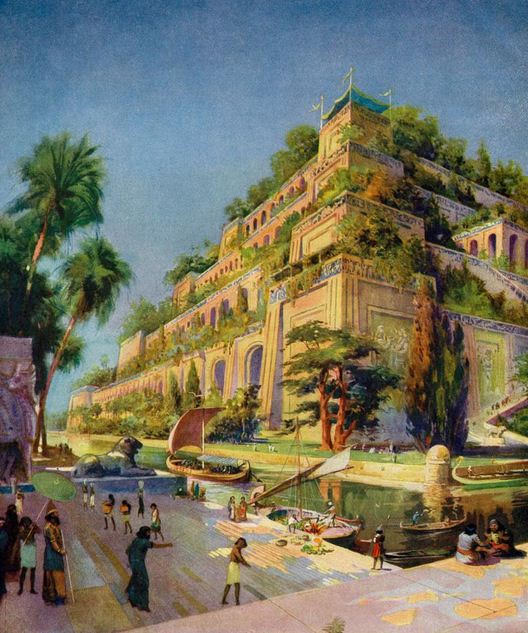

Then Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Nebuchadnezzar was a great builder, and it was he who made Babylon one of the most beautiful cities of the ancient world, home to one of the Seven Wonders.

He built the famed Hanging Gardens of Babylon for his Median wife who missed the lushness of her homeland, and he also constructed the giant ziggurat of Etemenanki beside the temple of Marduk.

Babylon at this time must have been a sort of paradise on earth with the ziggurat as the doorway to the heavens. The walls of the city too, were so big that it was said that two chariots could pass each other as they drove along the top of the walls.

Ishtar Gate of Babylon at Pergamon Museum Berlin

When the Seleucids came onto the scene and Babylon’s power and beauty faded into history, the population was moved to Seleucia, one supposes to bolster the economy of the great new capital envisioned by Seleucus I.

There was a lot of history at Babylon, and it’s not improbable that all the Romans who marched through there thought of Alexander as they approached, including Severus.

But Babylon was a very different place when the legions marched on it late in A.D. 198.

Just as Seleucia had been abandoned, so too was Babylon. And so, with barely a drop of blood being shed, the Romans walked into this ancient city of faded glory in stern silence, their prize almost too easily won.

Ruins of Babylon (Wikimedia Commons)

It was time for the real battle.

With Seleucia and Babylon basically given over to Rome and Severus’ legions, the forces of Rome and Parthia converged on the capital of Ctesiphon.

This time, the Parthians were waiting.

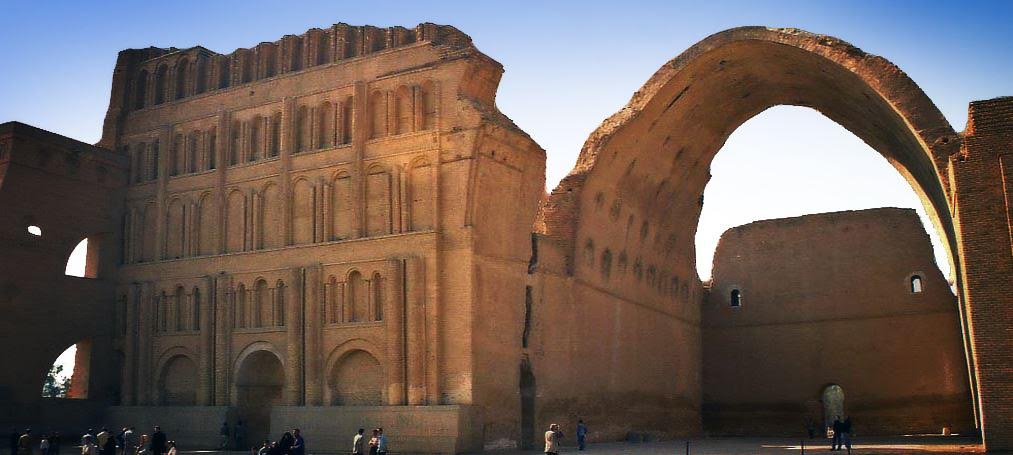

Ctesiphon, compared to the other cities we have seen, was a relatively new settlement on the east bank of the Tigris River, facing Seleucia. It was built around 120 B.C. on the site of a military camp built by Mithridtes I of Parthia. At one point in time, it merged with Seleucia to form a major metropolis straddling the river.

Ctesiphon’s ruins today, including the great audience hall.

During the Roman-Parthian wars, Ctesiphon did not have an easy time of it. It was captured by Rome five times in its history, the last time by Septimius Severus who burned it to the ground and enslaved much of the population.

The Greek geographer, Strabo, describes the foundation of Ctesiphon here:

In ancient times Babylon was the metropolis of Assyria; but now Seleucia is the metropolis, I mean the Seleucia on the Tigris, as it is called. Nearby is situated a village called Ctesiphon, a large village. This village the kings of the Parthians were wont to make their winter residence, thus sparing the Seleucians, in order that the Seleucians might not be oppressed by having the Scythian folk or soldiery quartered amongst them. Because of the Parthian power, therefore, Ctesiphon is a city rather than a village; its size is such that it lodges a great number of people, and it has been equipped with buildings by the Parthians themselves; and it has been provided by the Parthians with wares for sale and with the arts that are pleasing to the Parthians; for the Parthian kings are accustomed to spend the winter there because of the salubrity of the air, but they summer at Ecbatana and in Hyrcania because of the prevalence of their ancient renown.

Being built by the Parthians, Ctesiphon, unlike Seleucia, Babylon, or the other places we have discussed, was a Parthian invention. Probably the greatest structure of this capital was the great, vaulted audience chamber, or hall, which seems to be all that remains today. In truth, there is very little information on other structures within Ctesiphon itself.

Ctesiphon from the air

The final sack of Ctesiphon by Severus’ legions in A.D. 197 was a brutal affair, and one that ended that city and provided the death blow to the Parthian Empire.

In A Dragon among the Eagles, the Roman attack on Ctesiphon is one of the major battle scenes which I had envisioned a long time ago. Imagine, almost thirty legions lined up on the other side of the river with the entire force of Parthian horse archers and heavy cataphracts awaiting them.

The Romans had to cross the river, gain a beachhead, and then push forward. In the end, Rome prevailed, but at great cost to the troops.

One would have thought that with the sacking of the Parthian capital, all would be finished, but there was another score for Rome to settle, another city to take – the desert city of Hatra.

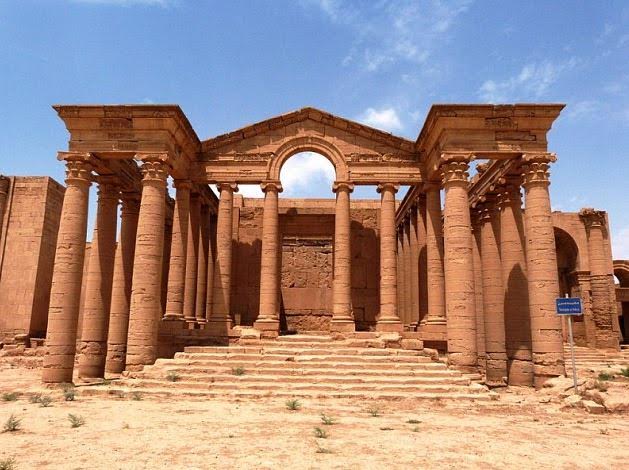

As I write this, I have a pang of sadness, for while I was researching and writing about Hatra and the Roman siege there, extremist groups in the Middle East were in the process of the wonton destruction of this ancient heritage site. Writing this part of the book was indeed an odd experience.

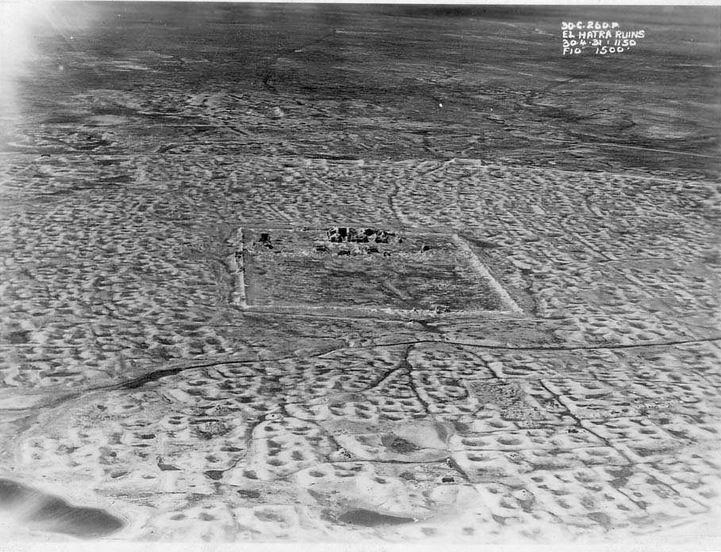

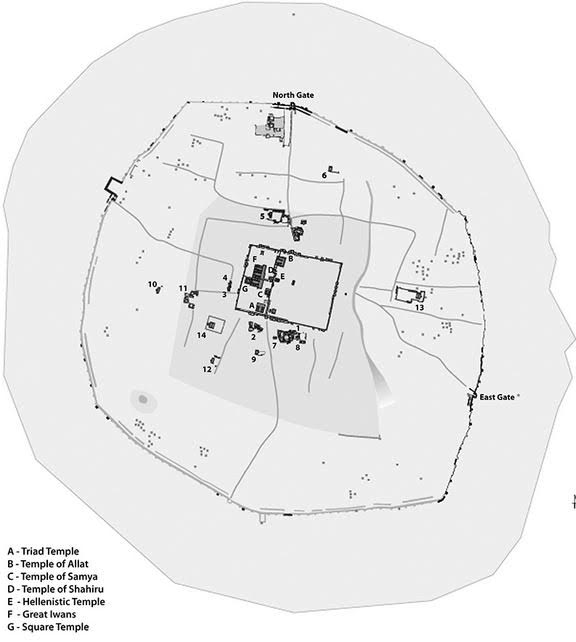

Hatra is located in modern Iraq, about 290 kilometers north of Baghdad, on the Mesopotamian desert, far from either the Tigris or Euphrates. It was built by the Seleucids, those Hellenistic giants we’ve heard so much about, around the third century B.C.

Hatra – old survey aerial photo

It flourished under the Pathians too as a center of religion and trade during the first and second centuries A.D. What is fascinating about Hatra is the harmony and religious fusion it represented. This remote desert city was a place where Greek, Mesopotamian, Canaanite, Aramean, and Arabian religions lived peacefully side-by-side. And for 1,400 years it was protected and preserved by Islamic regimes, until it was destroyed in 2015.

It was the best-preserved Parthian city in existence.

Hatra before the 2015 destruction

When Septimius Severus turned his attention on Hatra after the fall of Ctesiphon, it was with a goal of doing what no other Roman, even Trajan, had been able to do.

It was personal too, for Hatra and its ruler, Abdsamiya, had supported Pescennius Niger against Severus in the civil war.

But there were a few reasons Hatra had withstood Roman sieges, including the two attempted by Severus in his Parthian campaign.

First of all, Hatra was remote, stranded out in the desert with its own water source within the walls, but none without. The nearest water was over forty miles in any direction. A legion could only march a maximum of twenty-five miles in one day. So, thirst for those laying siege was a big factor.

Then there were the walls – two of them. Hatra was protected by immense, circular, inner and outer walls, the diameter of which was 2 kilometers, or 1.2 miles. Along these massive walls were 160 towers, making this island fortress of the sand seas no easy target.

Hatra Map (with temples labelled)

At Hatra’s heart were the sacred buildings of the gods of various religions, gods whom many believed protected the city from attack.

The temples within Hatra covered a total of 1.2 hectares, and that area was dominated by the Great Temple of Bel which was about 30 meters high.

Hatra withstood two major attacks by Roman emperors, Trajan and Severus. Every time, Hatra’s walls, and her gods, turned Rome back.

Cassius Dio describes Severus’ last siege of Hatra:

He himself made another expedition against Hatra, having first got ready a large store of food and prepared many siege engines; for he felt it was disgraceful, now that the other places had been subdued, that this one alone, lying there in their midst, should continue to resist. But he lost a vast amount of money, all his engines, except those built by Priscus, as I have stated above, and many soldiers besides…

When the walls were breached, Severus gave the Hatrans time to consider surrender, as he respected the religious importance of the place, especially the temple of the Sun God. But the Hatrans were stubborn, and the troops were fed up:

Thus Heaven, that saved the city, first caused Severus to recall the soldiers when they could have entered the place, and in turn caused the soldiers to hinder him from capturing it when he later wished to do so [threat of mutiny].

Once again, Hatra resisted being conquered by Rome, making it the only place Severus’ legions were not able to take.

One of Hatra’s many magnificent temples

It is sad that, in light of the events of 2015, it seems Hatra’s gods finally deserted it.

To see more of Hatra before its destruction, you can watch a UNESCO video by CLICKING HERE.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this march with the legions! In the next post, we’ll be going somewhere more civilized – the City of Alexander the Great!

Part V – The City of Alexander

Statue of Alexander in downtown Alexandria

In this fifth and final part of The World of A Dragon among the Eagles, we’re going to take a brief look at a city that has perhaps captured history-lovers’ imaginations more than any other – Alexandria.

There were, of course, many Alexandrias in the world, stretching from Greece to India, but the one we are going to discuss, and which provides the setting for the final third of A Dragon among the Eagles, is Alexandria in Egypt.

Alexandria was founded by Alexander the Great in about 331 B.C., near the westernmost branch of the Nile Delta. From a few scattered fishing villages, it grew to become one of the world’s great metropolises, a centre for trade, religion and learning the world had not really seen to that point.

There are many origin stories to the foundation of Alexandria, but the one I often refer to is that given by Arrian who says the following:

From Memphis he sailed down the river again with his Guards and archers, the Agrianes, and the Royal Cavalry Squadron of the Companions, to Canobus, when he proceeded round Lake Mareotis and finally came ashore at the spot where Alexandria, the city which bears his name, now stands. He was at once struck by the excellence of the site, and convinced that if a city were built upon it, it would prosper. Such was his enthusiasm that he could not wait to begin the work; he himself designed the general layout of the new down, indicating the position of the market square, the number of temples to be built, and what gods they should serve – the gods of Greece and the Egyptian Isis – and the precise limits of its outer defences. He offered sacrifice for a blessing on the work; and the sacrifice proved favourable.

A story is told – and I do not see why one should disbelieve it – that Alexander wished to leave his workmen the plan of the city’s outer defences, but there were no available means of marking out the ground. One of the men, however, had the happy idea of collecting the meal from the soldiers’ packs and sprinkling it on the ground behind the King as he led the way; and it was by this means that Alexander’s design for the outer wall was actually transferred to the ground.

(Arrian; The Campaigns of Alexander, Book III)

There is no real way to know whether this is true or not, but it is not impossible. Alexander was a man of vision, and learned in architecture, planning and much more. As a conqueror of the world, as many saw him, it was to be expected that he create one he hoped would have been a perfect city at the centre of the known world.

Alexander The Great Founding Alexandria by Placido Costanzi

The Egyptians had welcomed Alexander as a liberator against the Persians who had disrespected their gods. Alexander, on the other hand, respected Egypt’s ancient gods, and was even declared the son of Zeus Ammon by the famous Oracle at Siwa in the western desert.

Egypt’s new pharaoh had great plans for the city, but he died long before it could be completed. That task fell to Alexander’s friend and general, Ptolemy I, founder of the Ptolemaic dynasty, the last dynasty of Egypt before Rome took over.

Alexandria quickly became a destination that thrived under the Ptolemies, and as the resting place of Alexander the Great’s body, a major tourist destination. It was the greatest of the Hellenistic cities, dwarfing all others.

As time marched on, so did Rome.

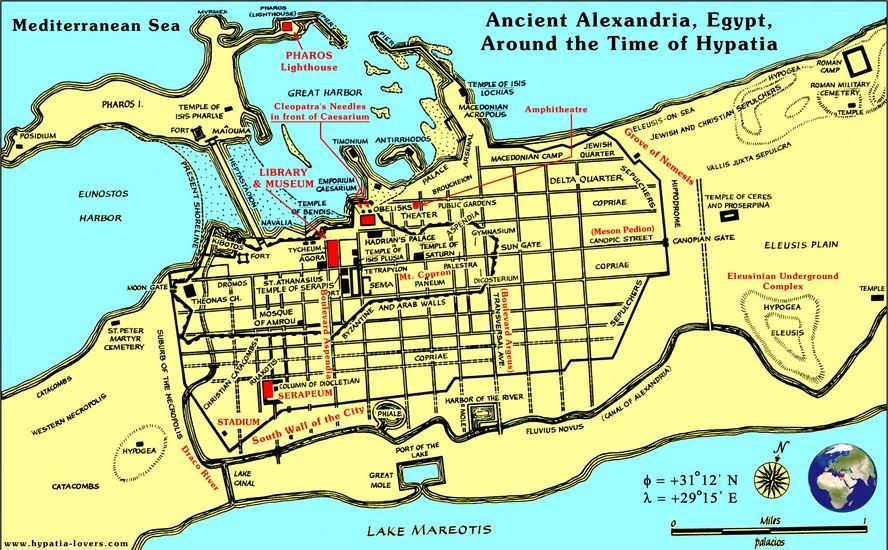

Ancient Alexandria in the years after Severus

Alexandria came under Roman jurisdiction in the will of Ptolemy Alexander in 80 B.C. Then, when a domestic dispute broke out between Ptolemy’s children, Ptolemy and Cleopatra, Rome, under Gaius Julius Caesar, stepped in to settle the dispute.

Most of you probably know this part of the story, how Caesar threw his weight behind Cleopatra, making her sole Queen of Egypt in about 47 B.C. They had a son, Caesarion, and the rest is history.

With the death of Caesar, Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra joined forces with the hopes of creating a new, greater Hellenistic world with Alexandria at the centre. But those hopes were dashed by Rome at the Battle of Actium where Octavian came out victorious and as a result, brought Alexandria under the control of Rome.

This is probably one of the most famous periods in Roman history, but it took place two hundred years before A Dragon among the Eagles.

What happened to Alexandria after the Battle of Actium? What did things look like for the city of Alexander?

Even though Rome remained the centre of the Empire, and basically the Mediterranean world, Egypt lost little importance. In fact, it gained, being as it was the granary of the Roman Empire, before the North Africa provinces came to the fore. Alexandria was so important that Octavian kept it under direct imperial control, making it so that Alexandria had no governor, and therefore, no one powerful enough to hold Rome’s grain hostage.

Fertile land of the Nile

Alexandria was beautiful and learned, but it was also tumultuous .

In A.D. 115 it was destroyed during the Greek-Jewish civil war. Luckily, that great phil-Hellene emperor, Hadrian, decided to rebuild the city so that it could continue to thrive.

By the time of A Dragon among the Eagles, when Emperor Septimius Severus and his legions came into Egypt at the conclusion of the Parthian campaign around A.D. 199, Alexandria was once again a metropolis to rival Rome.

Alexandria was always well placed at the crossroads of the world, beside the waters of the Nile Delta, at the edge of the Silk Road, and with free access to the rest of the Mediterranean Sea.

It was built on a narrow strip of land which was sandwiched between the Mediterranean to the north, and the fresh waters of Lake Mareotis to the south.

Alexandrian street scene in movie Agora

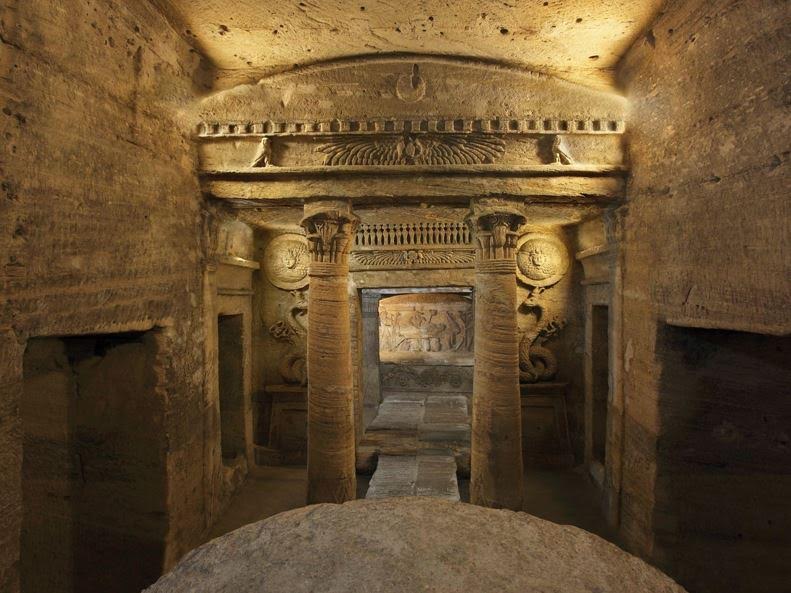

To the east of the city was the Eleusis Plain which contained an underground complex where the Eleusinian Mysteries, that major ritual of Ancient Greece, were presumably carried out. Closer to the sea on that side of the city were the Jewish and Christian sepulchers, as well as temples and Roman cemeteries beyond the Grove of Nemesis.

On the western side of the city, beyond the Draco River which ran along the south of the city and into the Fluvius Novus, the Great Canal of Alexandria, was the western necropolis which also contained Christian catacombs.

Alexandrian catacombs with mixture of Egyptian, Hellenistic and Roman styles

If you have seen the movie Agora, with Rachel Weiss, you will have seen a later, dirtier recreation of Alexandria from the time of this particular story.

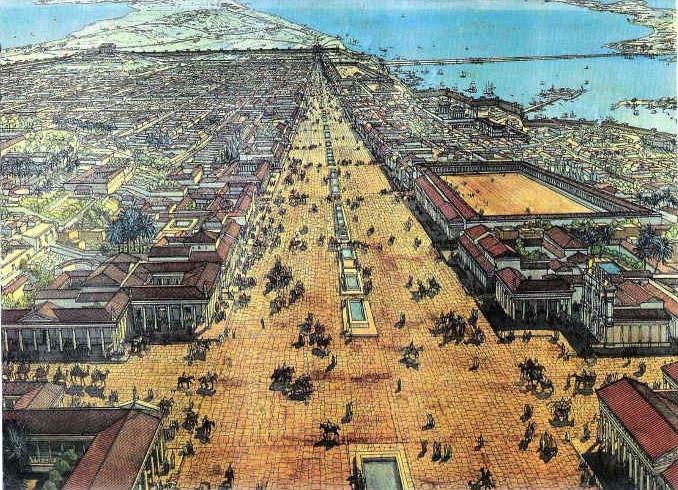

At the heart of Alexandria were the temples and palaces, and the Cema destrict where the tomb of Alexander the Great was located. Through it all ran the great city street known as the Canopic Way.

Alexandria’s Canopic Way (artist impression by Egyptologist Jean-Claude Golvin)

The Canopic Way, with the Sun Gate in the East, and the Moon Gate to the West, was ancient Alexandria’s main artery. It was the place to see and be seen, where giant litters carrying perfumed ladies went back and forth in the shadow of luxurious villas and temples. There were huge fountains running down the middle of the thoroughfare. Perhaps the Canopic Way was a sort of ancient version of Rodeo Drive, or 5th Avenue?

The success and livelihood of Alexandria did not necessarily stem from the richness of the street, nor the number of its temples, but rather from the Great Harbour which was faced by the royal palaces, agora, and the Great Library.

Across the man-made mole known as the Heptastadion, a bridge of about seven stades long, was the island of Pharos, and the structure that beckoned all the world to Alexandria – the Lighthouse.

The City of Alexander today

As one of the wonders of the ancient world, the great lighthouse of Alexandria set this city apart, and if that was the beacon, the library, for many, was what awaited them. It has been said that the previous library, that which stood during the reign of Cleopatra, burned down, and all the treasures it contained with it.

However, there are some theories that say the great library was never fully destroyed, that many of the works survived and that the library continued to send people out into the world to collect copies of every book or work ever created.

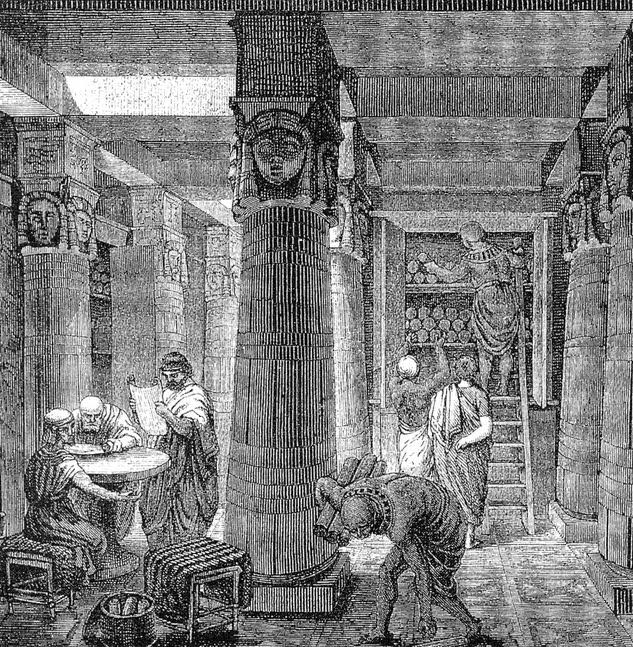

Library of Alexandria

I wonder if Alexandria would have lived up to the Conqueror’s expectations as he was laying out the city with his men’s rations, prior to his defeat of the Persian Empire?

It is ironic that the body of Alexander also became a big draw in Alexandria, for people came from around the ancient world to see this titan among men.

Augustus himself stopped to see Alexander’s body after the Battle of Actium, and successive emperors did likewise, including Septimius Severus who, for some strange reason, closed Alexander’s tomb to the public prior to going on a Nile cruise with his wife, Julia Domna.

Writing about this ancient city was no easy feat. First of all, I had to discover which structures were actually there during this time, and which I could not include.

The Pharos (17th century depiction)

It was also fun writing about Alexandria, in comparison to Rome, for it was generally believed that Alexandrian morals were much looser than those of Rome, making it something of a brilliant, seedy, learned metropolis.

When Lucius Metellus Anguis arrives in Alexandria, a city he has dreamed of visiting for a long time, he is torn between two worlds.

This made for some interesting and fun storytelling.

But it seems to me, after the research I’ve done, and after having written in that world, that Alexandria was anything but uniform, despite its logical grid of streets laid out by Alexander.

Alexandria was a world of contrasts, of perhaps the worst and the best that life had to offer. It preserved culture, and destroyed it, but it always rose from the ashes.

Riotous Alexandrians in the movie Agora

The glory days of its early Hellenistic existence were long gone, but perhaps under Rome, it experienced a revival that may not have been possible under the drunken ancestors of Cleopatra? I’m not sure, but if Cleopatra’s father saw the need to have Rome care for it after his death, there must have been a reason for it.

Antony and Cleopatra