Happy Saturnalia, everyone! Or, as the Romans said, Io Saturnalia!

December 17th was the official start of Saturnalia in the Roman Empire, and for seven days the Roman world, and especially Rome itself, experienced what can only be described as a carnival atmosphere.

Just as Christmas is a time of year that many people look forward to, so too was Saturnalia for Romans, free and slave.

Today we’re going to take a brief look at some of the customs that surrounded this ‘the best of days,” as the poet Catullus called it.

Saturnalia was basically a winter solstice festival in honour of the god Saturn, the chthonic (of the earth) Roman god of seed sowing, who was often equated with the Greek god Cronus. As an agricultural deity, his symbol was a scythe.

The primary temple for this Roman deity was at the foot of the Capitoline Hill, across from the Rostra, the Temple of Concord, and the arch of Septimius Severus.

The festival of Saturnalia was originally a single day, but eventually ran from December 17th to December 23rd, ending on the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, or the birthday of the Unconquerable Sun. The three days from December 17th to the 19th were considered to be legal holidays on which no work was done. Schools, gymnasia and courts were closed, and no war was waged.

Saturnalia was a sacred time of year in the Roman calendar, but oddly enough, there is no single, full description of the festival. What we know comes from various references in ancient sources, mainly Macrobius whose work on Roman religious lore is set during the festival.

So, what do we know about the festival of Saturnalia, and what traditions did people keep at that time of year?

In ancient Rome, we know that the festivities began on December 17th with a sacrifice at the Temple of Saturn in the Forum, in which the priest performed the ceremony in the Greek fashion, ritus Graecus, with his head uncovered. In the temple, the feet of Saturn’s statue were normally bound up with wool, but for Saturnalia, the wool was removed, and some believe this symbolized the liberation that many felt during the festival.

After the sacrifice, which may have been a suckling pig, there followed a grand public banquet, or convivium publicum, which was paid for by the state. A statue of Saturn was placed upon a couch for this event so that the god could preside over the festivities.

As a festival of light, or the solstice, wax candles, or cerei, were lit everywhere and given as gifts. The light may also have been considered a symbol of the quest for knowledge and truth, something to go along with this season of hope for many in the dark days of winter.

Another symbol of the season was holly, which was considered sacred to Saturn. Sprigs of this were also given as token gifts. Many other gifts were given at this time of year, mainly on December 19th, which was the day of the sigillaria, the day of gift-giving.

In addition to wax candles, gifts could include pottery, writing tablets, dice, knucklebones, combs, toothpicks, hats, knives, lamps, balls, perfumes, and toys for children. If you were among the rich, exotic animals or slaves might even be given!

Figurines were also a gift that was given, and these have something of an interesting history. One thought is that this particular gift stemmed from the giving of toys to children. However, another, darker possibility for the giving of figurines is that they were intended as substitutes for the human blood offerings that may have originally been offered to the earth god Saturn, in the early days of Rome, perhaps in the form of gladiatorial combat to the death.

Some sigillaria were similar to the gifts we get in Christmas crackers today, but they could be much more elaborate too.

In addition to the public celebrations of Saturnalia, the festivities continued at home.

On December 18th and 19th, domestic rituals of the family were observed, such as bathing, and the common sacrifice of a suckling pig to Saturn.

Gifts were given among the family on the day of the sigillaria, but also in the days to come.

One interesting tradition was that the usual clothes worn by Romans, such as the toga or plain tunica, were discarded during Saturnalia in favour of colourful clothes known as synthesis, which were a mish-mash of patterns and colours. They were the Roman party clothes of Saturnalia! Along with the synthesis, Roman men also wore a felt or leather conical cap known as a pileus.

Saturnalia was a time of role reversal, a time when the opposite of normal was acceptable.

For instance, during Saturnalia gambling was permitted in public, with the stakes being either coins or, oddly enough, nuts!

Overeating and drunkenness were common, as was guising, which was the wearing of masks or costumes to take on another persona.

Thou knowest not what evening may bring.

(Macrobius. Saturnalia)

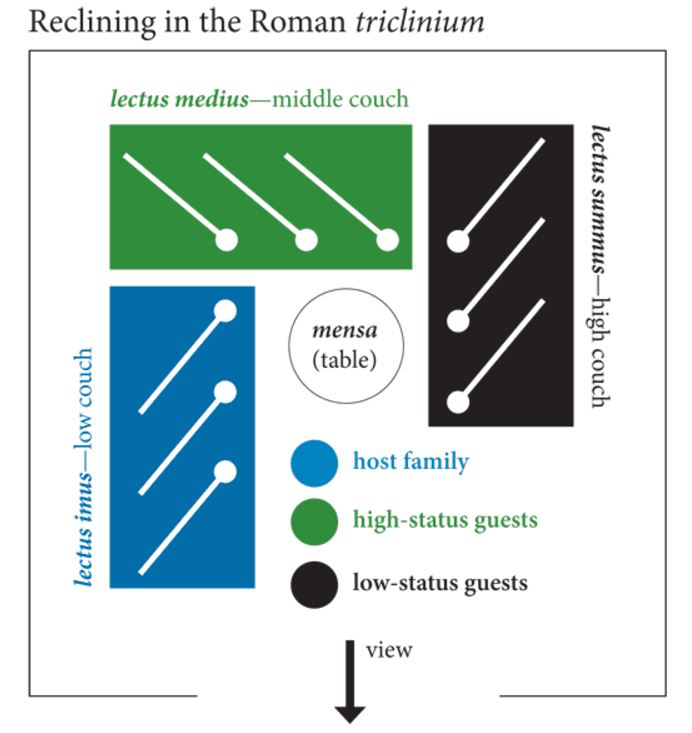

However, perhaps the most commonly known tradition of Saturnalia was the role reversal of masters and slaves. Traditionally, masters would serve their slaves a meal of the sort that they would usually enjoy, sigillaria would be given, and the slaves were even at liberty to insult their masters without fear of retribution.

Citizens or slaves might even be elected the ‘King of Saturnalia’ at the banquet at which time they could give absurd orders that had to be obeyed.

If this seems like a hectic summary with myriad different traditions and goings on, you’d be right. Just as with Christmas today, everyone likely had their own unique take on the traditions of the season. Roman religion was highly customizable!

You’d also be correct in assuming that some of the traditions of Saturnalia feel very familiar. At Christmastime, people eat and drink more than is usual (if they are so fortunate), there are a couple of days off work, gifts are given, holly (and perhaps ivy) is hung, candles are lit, and more.

Around the winter solstice, it seems that many cultures and religions find cause to celebrate.

So, from December 17th this year and in the run-up to Christmas, spare a thought for the Romans who certainly knew how to throw a good party this time of year.

Thank you for reading, and Io Saturnalia!

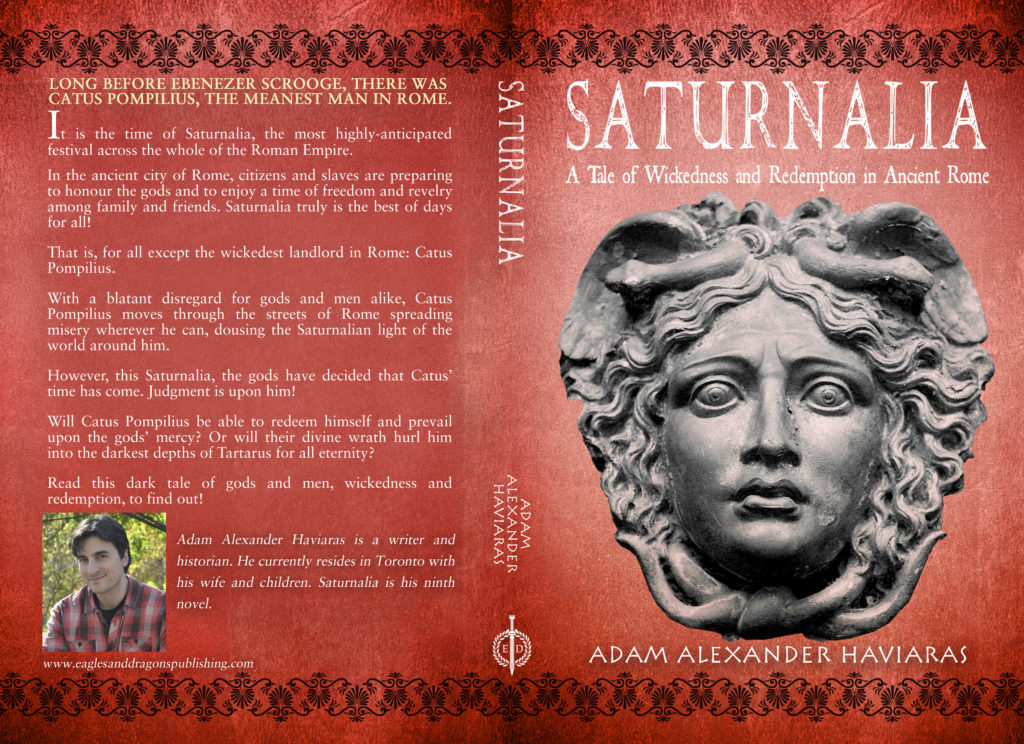

For those of you who are fans of historical fantasy set in ancient Rome, you may want to check out one of Eagles and Dragons Publishing’s latest releases, Saturnalia: A Tale of Wickedness and Redemption in Ancient Rome.

Much of the research for this post was done for the writing of this new book, so if you would like to see many of these ancient traditions come to life, you’ll want to check it out by CLICKING HERE.

Lastly, and for a bit of fun at this festive time of year, check out this hilarious video and song by the Ashmolean Latin Inscriptions Project and members of Oxford’s Faculty of Classics: