It’s been a while since I last posted in the Ancient Everyday series.

Today, we’re going to take a very brief look at childbirth in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome.

Now, as a man, my input and views on childbirth are somewhat limited, so I would invite my female readers out there to jump in with their comments at any time. I’m a father, and I’ve been present at the birth of my own children, but I would never presume to fully comprehend mysteries, and agonies, that women go through when it comes to bringing a tiny human into the world.

Let’s face it, we’re extremely lucky today as far as obstetrics and the technologies we have to help mothers and children safely navigate the process of pregnancy and birth.

That was not the case in the ancient world. Pregnancy and birth were risky affairs, and as with many aspects of life, the ancients called on specific gods and goddesses for help when it came to childbearing and birth.

Egyptian God, Bes

The Egyptians offered prayers to the god Bes, a god of marriage and jollity, but also a protector of women and children in childbirth. Bes was not your typical Egyptian god. He is portrayed as an ugly dwarf with a feather crown, sometimes holding a tambourine.

His consort, Tauert, was also prayed to as someone who assisted all females, regardless of station, in childbirth. Tauert was portrayed as a pregnant, female hippopotamus.

In ancient Greece the goddess two whom prayers and offerings were made was Artemis, under her two epithets Kourotrophos (nurse) and Locheia (helper in childbirth).

Now it might seem odd that people prayed to the virgin goddess for protection in childbirth, but in myth, Artemis was said to have been present when Leto, her mother, gave birth to Apollo on Delos. She was considered, in some ways, the first midwife.

Artemis

It is interesting to note ancient Greeks believed that women who died suddenly in childbirth were helped to a painless death by Artemis who showed them mercy by piercing them with one of her arrows.

The ancient Greeks also prayed to Hecate as a goddess of women and nurturer of children, as well as Hera, the Queen of the Gods who sometimes served as a goddess of childbirth in her capacity as goddess of marriage.

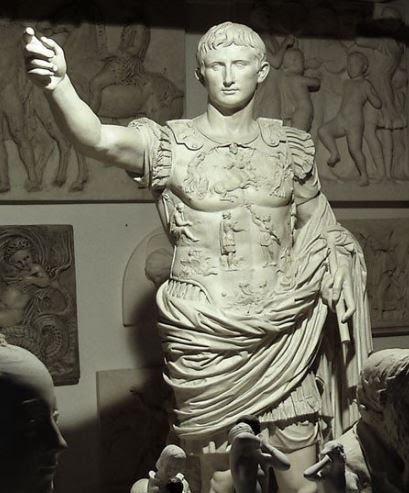

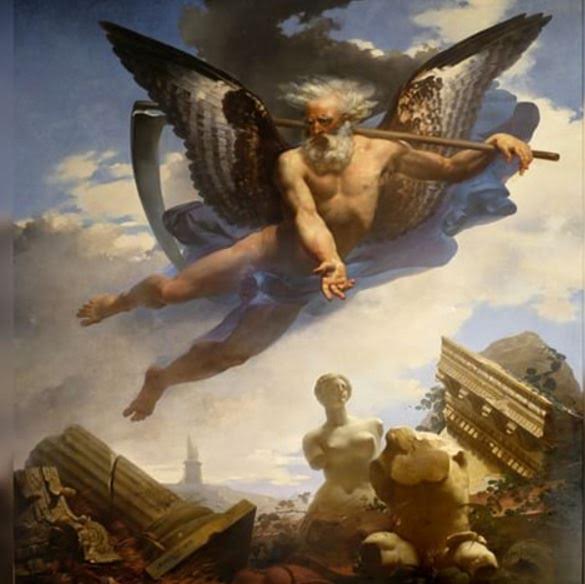

Roman Goddess, Juno – Queen of the Gods

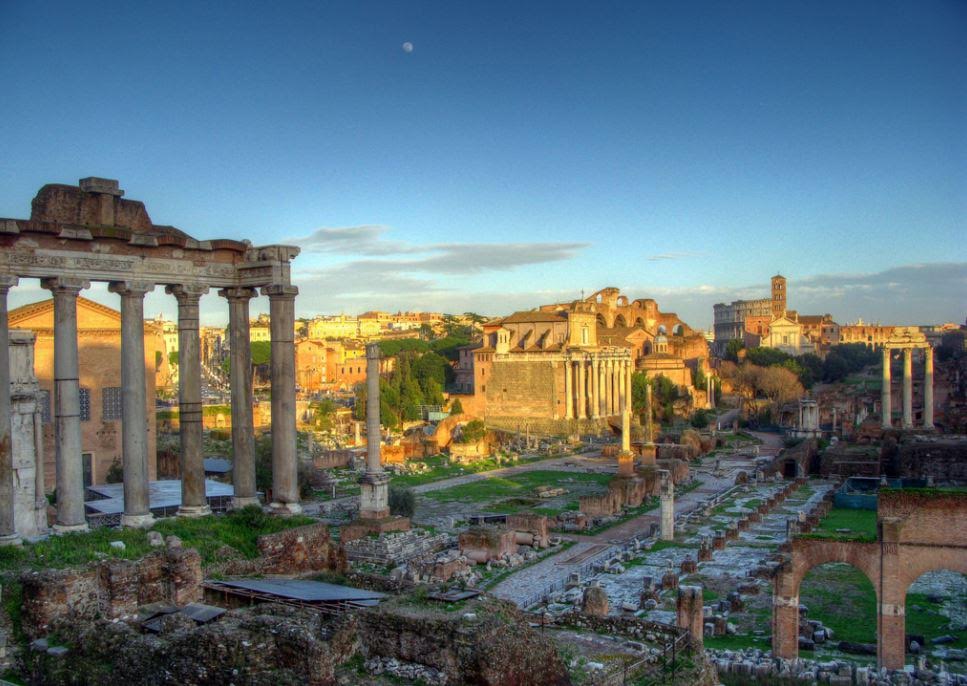

The Romans had many gods and goddesses to whom they prayed for help, and Juno, Queen of the Gods, was first and foremost under the epithets of Lucina, and Opigena.

Another goddess with a major role to play was Carmentis, a water goddess who was also a prophetic goddess of protection in childbirth. Carmentis had her own festival, the Carmentalia, and a temple on the Capitoline Hill.

A third goddess whom the Romans prayed to for a safe and successful childbirth was Matuta, the goddess of dawn and young growth.

It must have been a comfort to have so many gods to pray to, but that may also be indicative of the high risks involved.

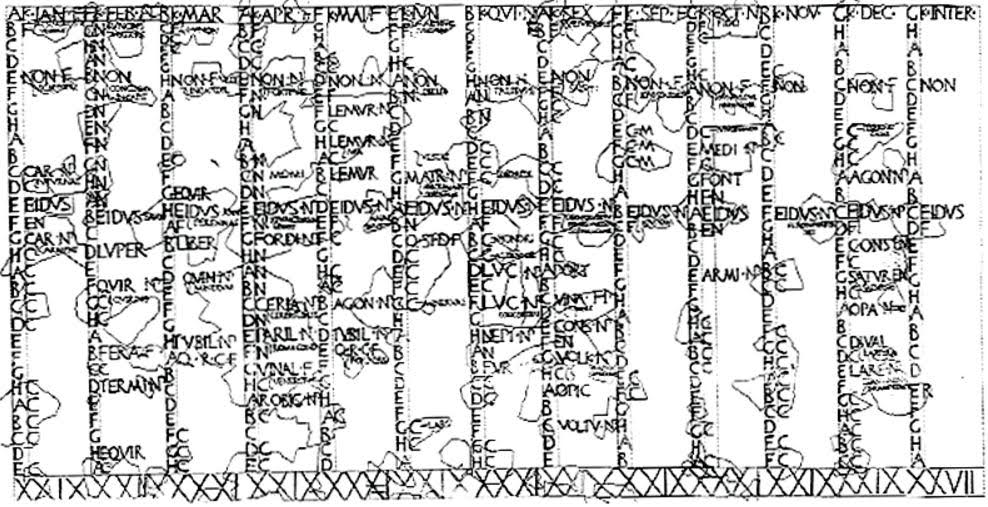

Ancient Coin with image of Silphium plant on one side, and heart-shaped Silphium seed on the other

Because it was so dangerous to bring a child into the world, and because families could not always afford to feed or provide dowries for all their children, contraception was something that was used in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome.

Most of the methods used seem to be herb and plant-based, and included things like acacia, honey, Queen Anne’s Lace, date palm, willow, Artemisia, myrrh, and the now extinct silphium plant, among others. Some of these are apparently used in spermicides today.

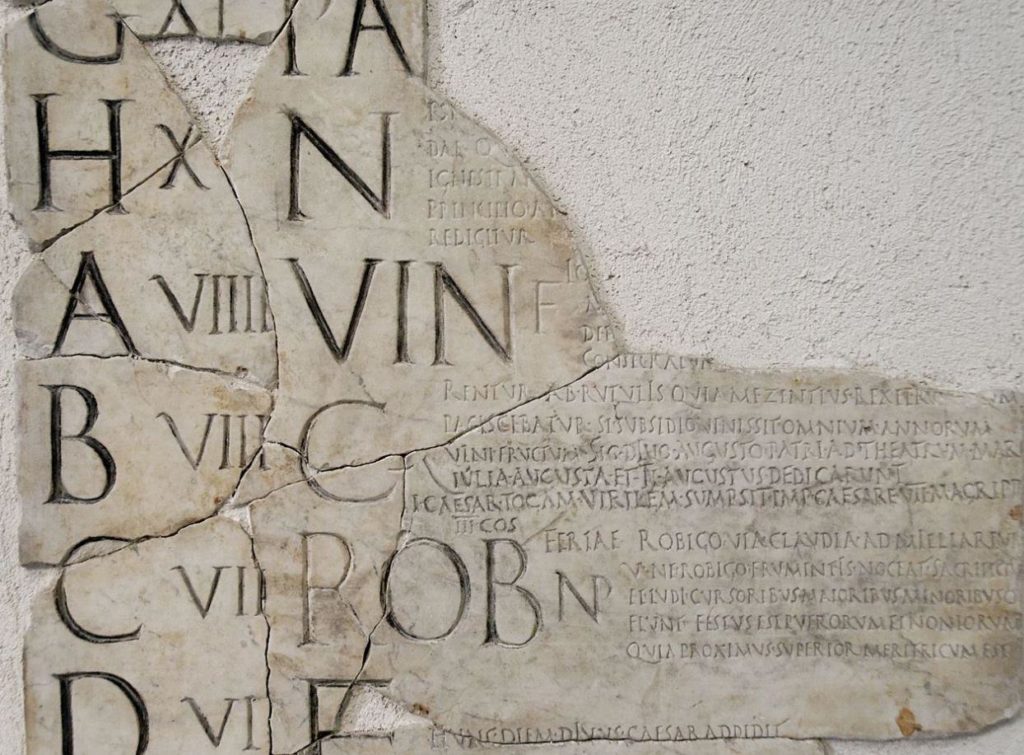

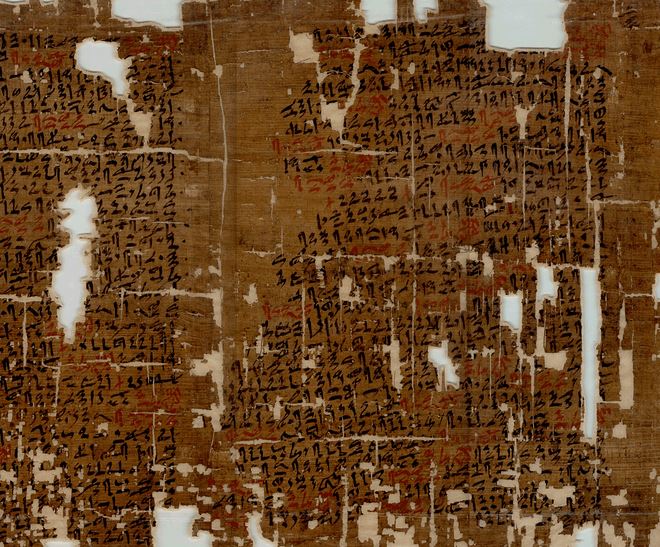

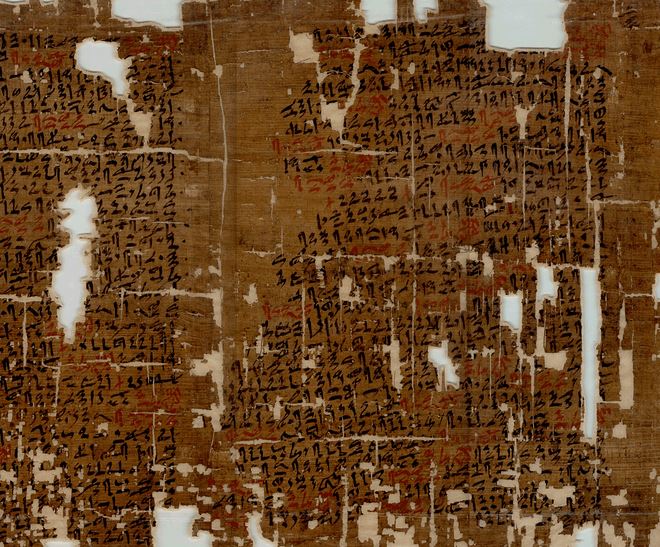

The Egyptian Kahun Papyrus from c. 1850 B.C. actually contains a lot of information on birth control and is the oldest known gynaecological treatise.

Egyptian Kahun Papyrus – The World’s first known gynaecological treatise

But we are talking about having children in the ancient world. Today, most husbands (I would hope) are in the room to support their wives and be there when their child are born. It happens at the hospital or birthing centre (most of the time), and there is a doctor/obstetrician to help the delivery.

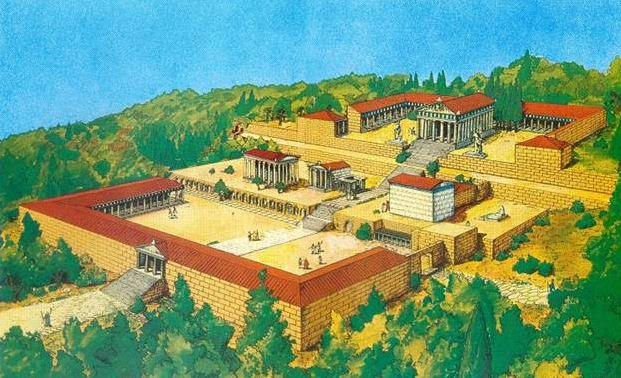

In the ancient world, births took place at home. There were no hospitals, except for those at healing centres like Kos and Epidaurus, and oftentimes, anyone who had been ‘in touch’ with childbirth was not permitted to enter sacred sanctuaries anyway for fear of contaminating the place.

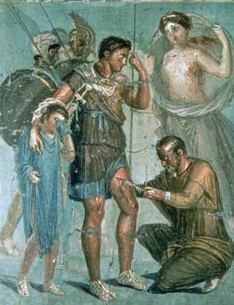

In Egypt, Greece, and Rome, midwifes were a constant. Today, midwifery seems to have made a big comeback, but in the ancient world, the midwife was always the one who helped women through childbirth. Their skills and knowledge were considerable. The only time a doctor might have been called in ancient Greece and Rome was if there were complications.

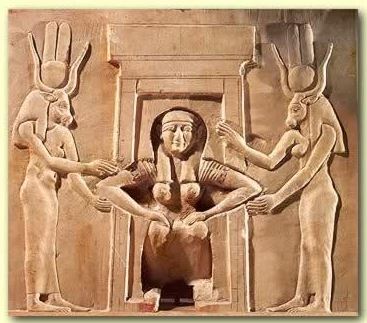

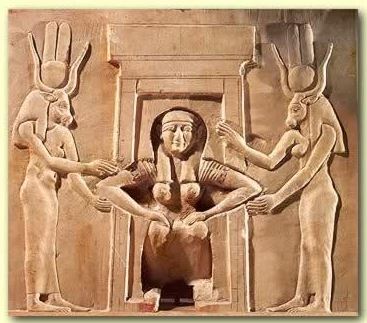

Egyptian birth – temple relief at the Ancient Egyptian Dendera Complex depicts a woman giving birth while squatting and attended by the two goddesses

It appears that in most cases, no men were present at the birth of a child, though there were often several people in attendance, including the midwife, the women of the household (mothers, grandmothers, aunts etc.), and any female slaves that were needed to help.

It was not considered proper for men to be present, and the only man who might have been there was the doctor if he was called.

What about the position for giving birth?

Well, in Egypt, it seems that women often knelt in a shaded spot or shelter to give birth.

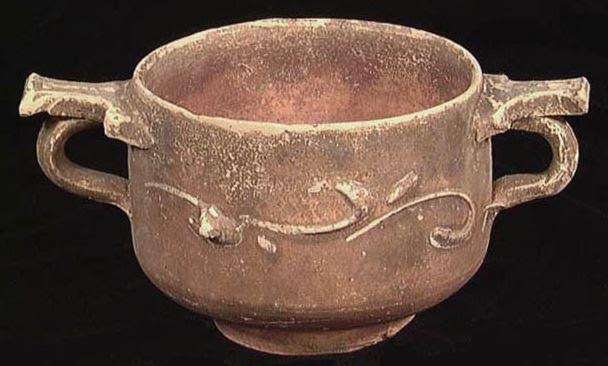

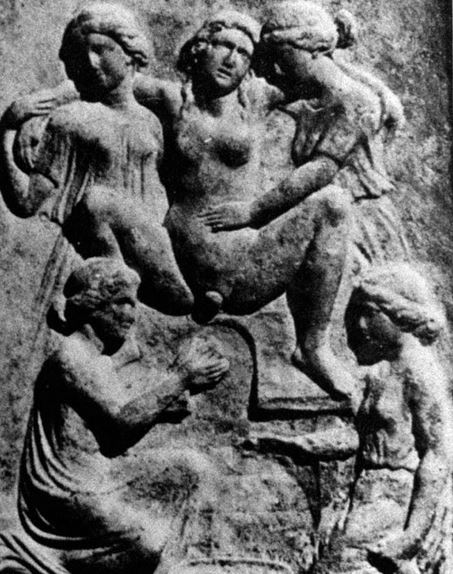

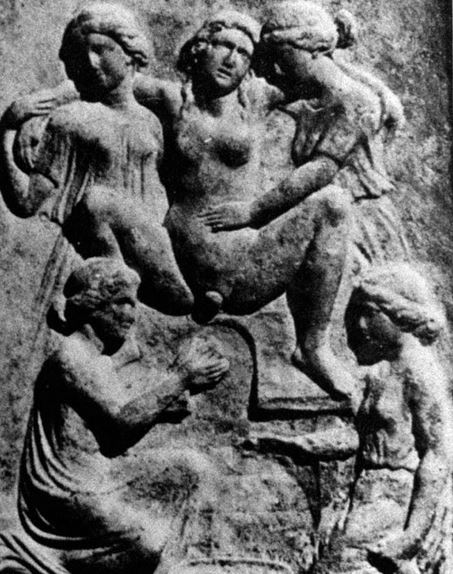

Relief of a woman in birthing chair

With modern hospital beds, women are in more of a lying-down position, with their backs propped up to give birth.

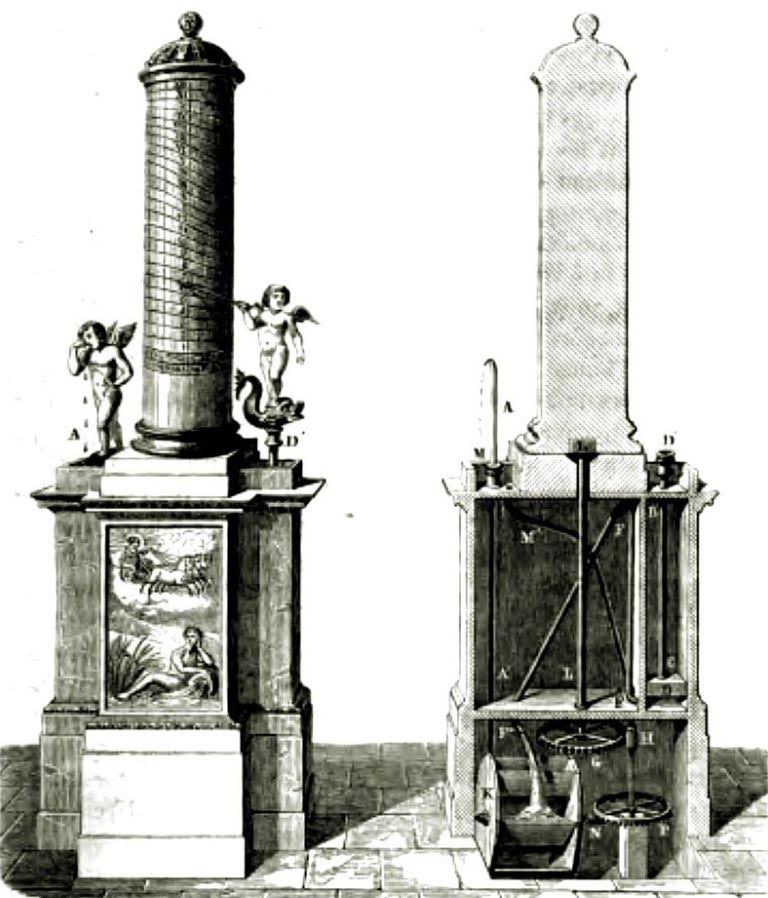

Interestingly, in ancient Greece and Rome, and in later centuries, birthing chairs were used. This was basically a wooden chair with arms, but no seat.

The midwife would kneel on the floor before the chair and help the woman from there, her hands wrapped in linen or papyrus so that the baby did not slip when she caught it.

It may be that couches were also used for giving birth, but I do wonder if midwives in ancient Greece or Rome might have had birthing chairs as part of their professional kit.

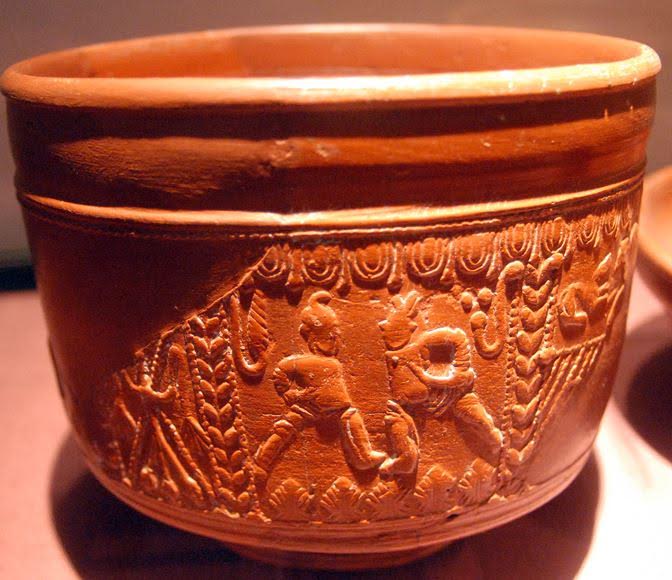

Roman birthing chair and midwife from plaque in Ostia

Mortality rates for women and children in pregnancy and childbirth were high in the ancient world, and from the little that I’ve read, the risk of death was extremely high in ancient Egypt. Many women died in pregnancy and childbirth, and infants who were born often did not survive the first few months.

Once a child was born, there was usually a ceremony for the naming and blessing of the child.

Funerary monument of a woman who died in childbirth showing her bidding farewell to her husband, mother and nurse who will care for her child

I could not find information on the specifics of an Egyptian ceremony (Egyptology is not my area of expertise), but I have read that water and ritual washing may have been a part of such a ceremony for newborns since water played a large part in Egyptian religious rituals. Perhaps my Egyptologist friends out there can shed some light on this subject?

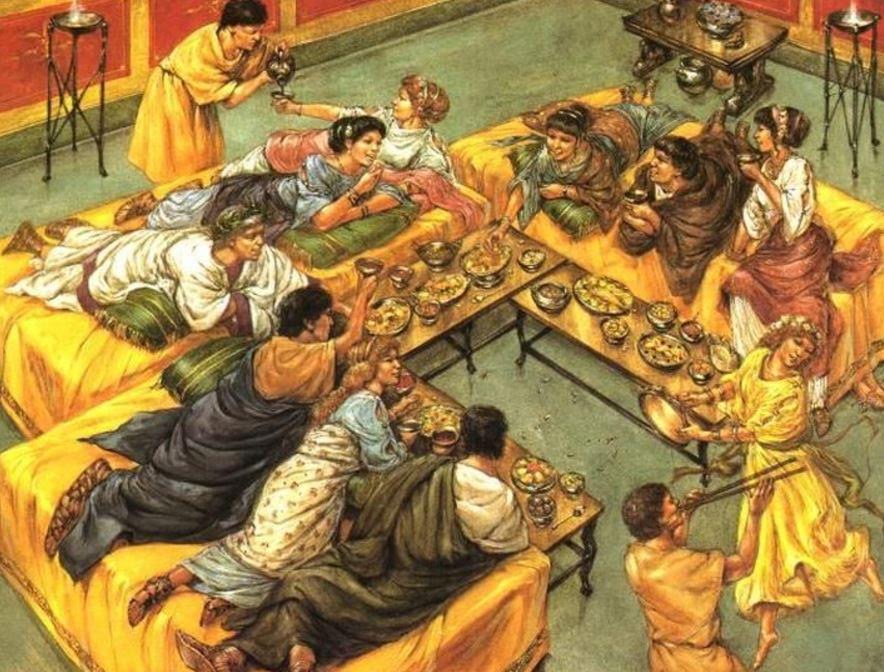

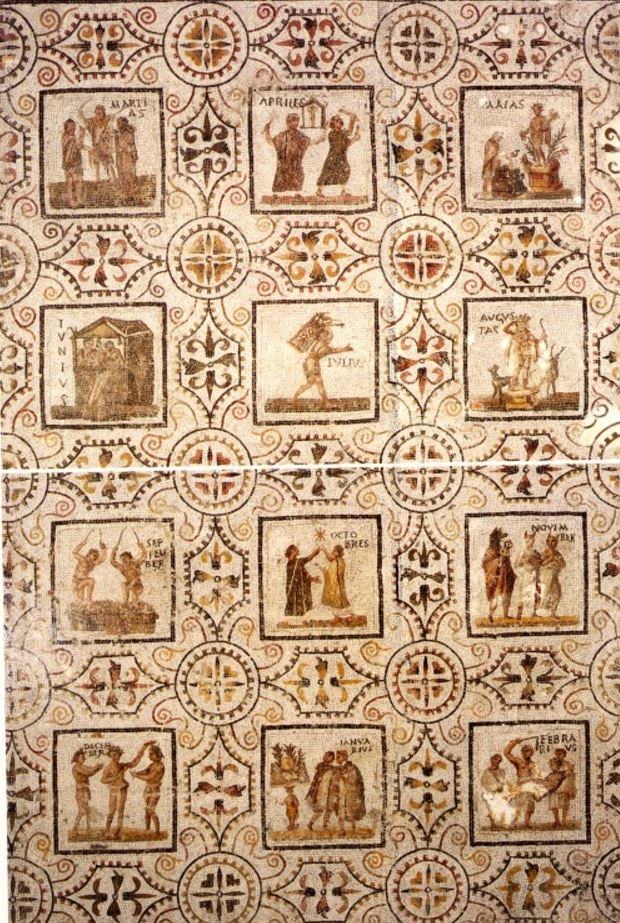

In ancient Greece, on the fifth or seventh day after a child was born, there was a purification ceremony and feast called the amphidromia, at which the child received its name. This involved a ritual and an evening feast to which guests brought presents for the child. If a boy was born, the house was decorated on the outside with olive branches. If it was a girl, the outer decoration consisted of garlands of wool.

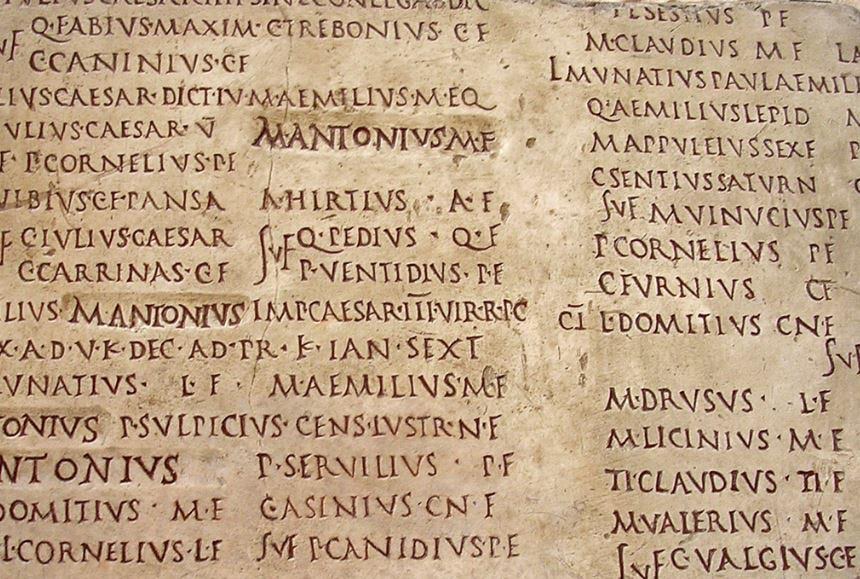

In ancient Rome, the naming ceremony was called a lustratio, and this took place nine days after the birth of the child. At this, offerings were made to the gods, there was a feast, and the child was introduced to guests.

In chapter twenty-one of my book, Killing the Hydra, I write about a Roman lustratio.

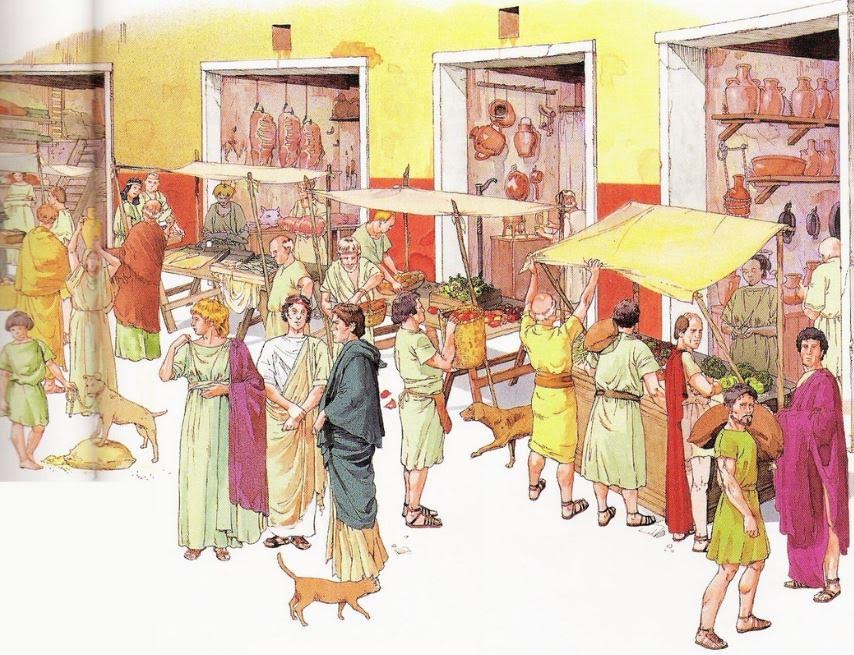

A family making their offerings to the Gods

Most people today cannot view the successful birth of a child with anything but gladness. And rightly so! It’s a beautiful thing, and most parents are happy when their child is born healthy, no matter if it is a boy or a girl.

However, in the ancient world, views of family and children could be quite different from our own.

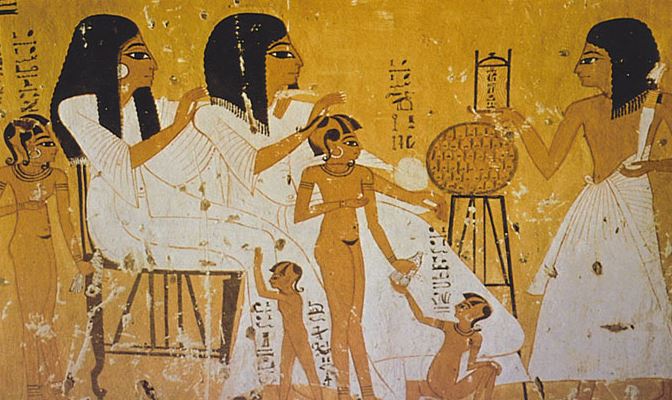

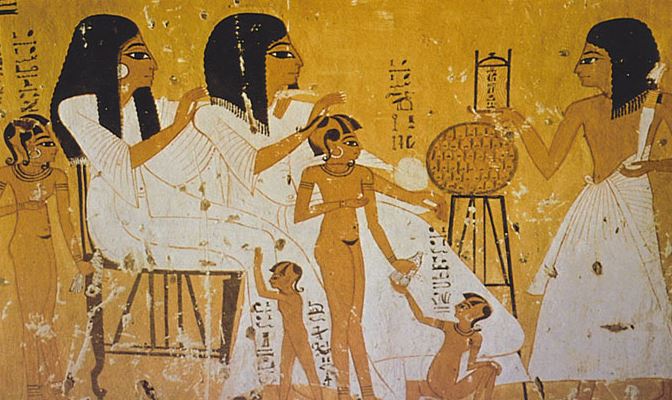

It seems that ancient Egyptians were devoted to their families and that they loved their children. This can be seen in the many images that survive of happy families, babies in their mothers’ arms, and children playing.

Egyptian women and children

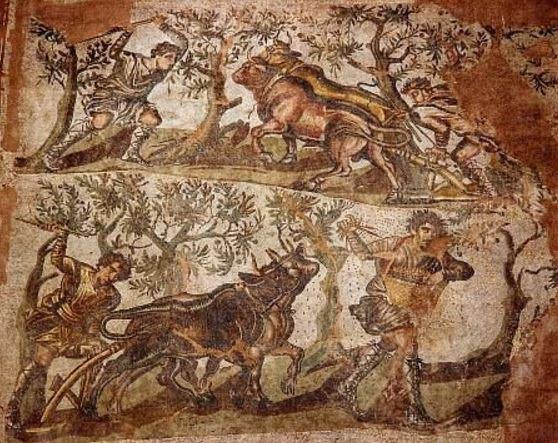

In ancient Greece and Rome, children were meant to be less visible, and stayed inside with the women. At birth, a Greek father or guardian decided whether to keep a child. In Rome as well, the paterfamilias had the power of life and death over his family members, and this included newborn infants whom the father could deny the right to be reared.

Children could be exposed or killed in ancient Greece and Rome, and had no place in public life.

Practices also differed by place. For instance, in ancient Athens, if a child was kept, it was swaddled, whereas in Sparta children were not swaddled at all, presumably to start toughening them up, or cull the weak.

It certainly seems harsh to our modern sensibilities, but the truth is that if a child managed to survive birth, decisions about their usefulness and whether to keep them were more often based on the sex, the number of children the family already had, ability to provide for that child, the future need for a dowry, and general health.

Children’s toys from ancient Greece

It’s odd, but most of the time, I tend to think that the past was much more exciting and interesting, more beautiful than our chaotic, modern society. I think most historians feel they were born in the wrong age!

But when I read about things like pregnancy, health, childbirth, and children in the ancient world, it makes me grateful we live in the age we do.

It’s not perfect by any stretch, but as far as childbirth, I would give that part of the ancient everyday a miss.

Statues of children from the sanctuary of Artemis at Brauron, Attica, site of an ancient orphanage

And let’s not think that all children in ancient Greece and Rome were treated badly. It is my hope that, despite the social mores of those sometimes harsher societies, Nature instilled in the mother and father of most children a love and need to care for their offspring that is timeless and powerful.

As ever, thanks for reading!

Aphrodite and Anchises with baby Aeneas