Salvete Readers and History-Lovers!

It’s been a while since our last blog on Religious Rites in Ancient Rome, and in that span of time a lot has happened abroad and at home.

Despite the lingering presence of COVID-19 in many countries around the world, some have started to risk staged re-openings, including our beloved Greece and Italy where summers would be incomplete without ancient sites and the sense-tickling blues of sea and sky. Eating al fresco is still a risky business, but people are trying things out.

I wonder if ‘re-openings’ were similar in the terrible wake of the Antonine Plague of the second century? Then, as now, the theatres and games must have been the last to open.

It has been an eventful period for myself as well. During this time of plague, my family and I decided to quit Rome for the quiet and less crowded countryside of Etruria. Well…in truth, we’ve completed our long-planned move from Toronto to Stratford, Ontario, home of the famous Shakespeare festival (yes, named after the English one!). Once again, as happened in ancient Rome or Elizabethan England, the theatres are dark due to plague. But they will re-open again!

But now for this week’s blog post…

During this pandemic, we have been hearing a lot about governments, how they have been dealing with this pestilence, how they have been trying to keep the populace safe, how they have developed economic plans for support and recovery at various levels and for various sectors etc.

So, I thought it would be a good time for a short, two-part blog series on government in ancient Rome.

What did government look like in the world of ancient Rome? How were decisions made? What did it look like in the Republic versus the Principate? What was the difference between the Popular Assemblies and the Senate?

In Part I of this series, we’re going to be taking a very brief look at the Popular Assemblies during the Republican era.

For a long time, Roman citizenship was something of value, something to be cherished for many reasons, not least of which was the ability to have a say in who was elected to political office, but also which legislation was passed in the growing empire that was Rome. Roman citizenship, for free men that is, was something to be proud of. It offered protection, commanded respect, and so much more.

All male citizens of Rome could vote on legislation and in the election of government officials, and this voting was done in the Popular Assemblies, or comitia. All male citizens were automatically members of a comitium, of which there were four.

The important thing to keep in mind is that these comitia met only to vote, not to discuss or initiate action.

Legislation, laws, or a proposed action (ex. to go to war against an enemy) was initiated by an elected magistrate and discussed by the Senate of Rome. This happened before being taken to the Popular Assemblies, or comitia, for a vote. In this way, the senators of Rome controlled the nature of legislation.

Denarius with image of a voter casting a ballot (Wikimedia Commons)

Laws were known as leges (singular, ‘lex’), and laws passed by the Plebeian assembly were known as plebiscita.

There was no discussion during assemblies, but there could be informal discussions known as contiones before a vote which male and female citizens, slaves and foreigners could attend, hence the importance of public opinion and the favour of ‘the mob’ in ancient Rome if you were a senator or magistrate who wanted something to be passed by the Popular Assemblies.

As Rome’s empire grew, many citizens could not vote because they were far from Rome where the voting took place.

To Romans, Rome really was the centre of the world.

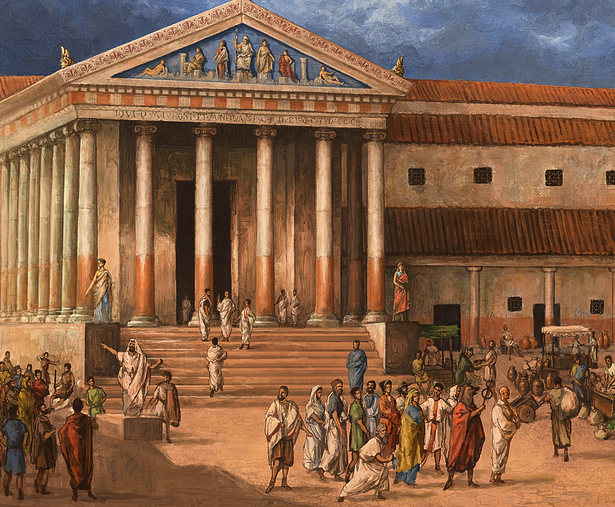

Ancient Rome (image from Ancient History Magazine)

There were four types of comitia in ancient Rome during the Republican era, and the first group were the comitia curiata.

In ancient Rome, there were thirty wards or curiae, ten wards for each of the three original tribes (Ramnes, Tities, and Luceres) of Rome. Just as we do today, people voted in their respective wards.

However, little is known of the comitia curiata. What we do know is that the comitia centuriata grew out of it, and that by the late Republic the comitia curiata met only formally to confer imperium on consuls and praetors.

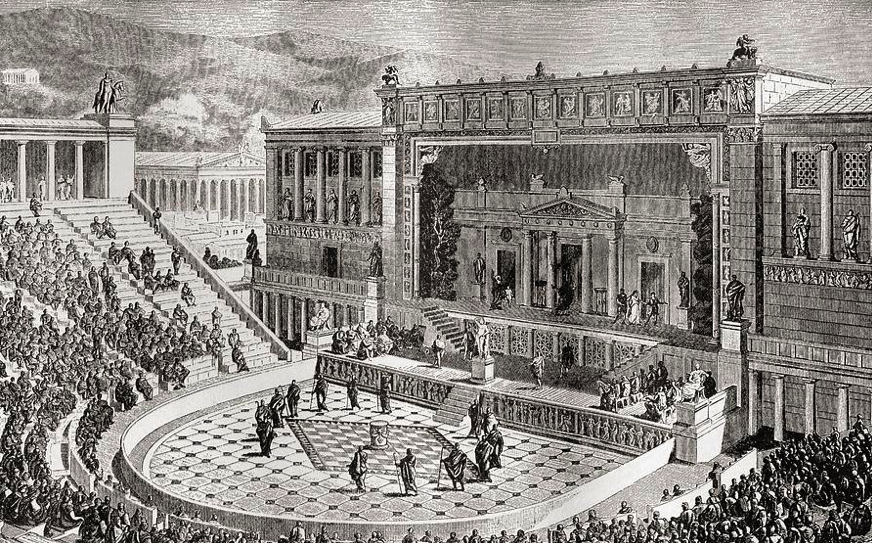

The next popular assembly we are going to take a look at is the comitia centuriata. This is the assembly that decided between War and Peace in ancient Rome, so you can imagine them meeting quite often as Rome’s empire expanded. They also elected higher magistrates and were the court of appeal for death sentences.

The comitia centuriata could only be summoned by a magistrate with imperium. They met on the Campus Martius (the Field of Mars) at Rome, and the voters of this assembly were divided into units called centuries, of which there were 373 in total. These centuries were based on male citizens’ ages and property asset values, the latter meaning that the poor had fewer votes. It was the rich who ran Rome.

Will it be War or Peace?

The third group of comitia we’re going to take a look are the comitia tributa or ‘assembly of the tribes’.

These comitia met in the Forum Romanum and the voters were divided into their thirty-five tribes, including the three original Roman tribes. They were summoned by consuls, praetors or tribunes for the purposes of electing lesser magistrates or to act as a court of appeal. They also voted on bills which the magistrates put before them.

Lastly, there was the concilium plebis, or Plebeian Assembly.

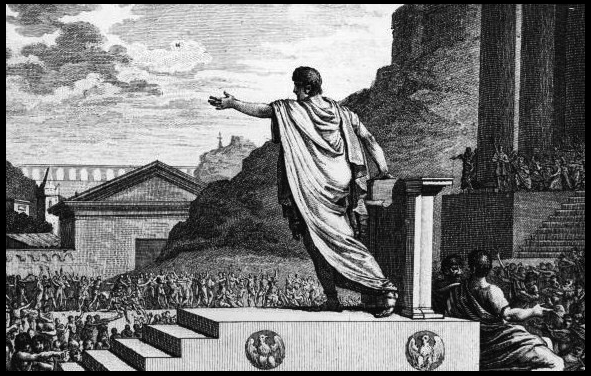

This assembly consisted of Plebeians only and met in the Forum Romanum. The citizens were divided into the thirty-five Plebeian tribes whose duty is was to elect tribunes and plebeian aediles. After 287 B.C., their resolutions or ‘plebiscita’ were binding on all citizens of Rome.

Gaius Gracchus, tribune of the people, presiding over the Plebeian Council (Wikimedia Commons)