Happy New Year, and welcome back to The World of Sincerity is a Goddess, the blog series in which we are taking a look at some of the research that went into our latest novel set in ancient Rome.

If you missed Part V on prostitution in ancient Rome, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In Part VI, we’re going to be exploring one of the most important theatrical and healing sites from the ancient world: Epidaurus.

We hope you find it interesting…

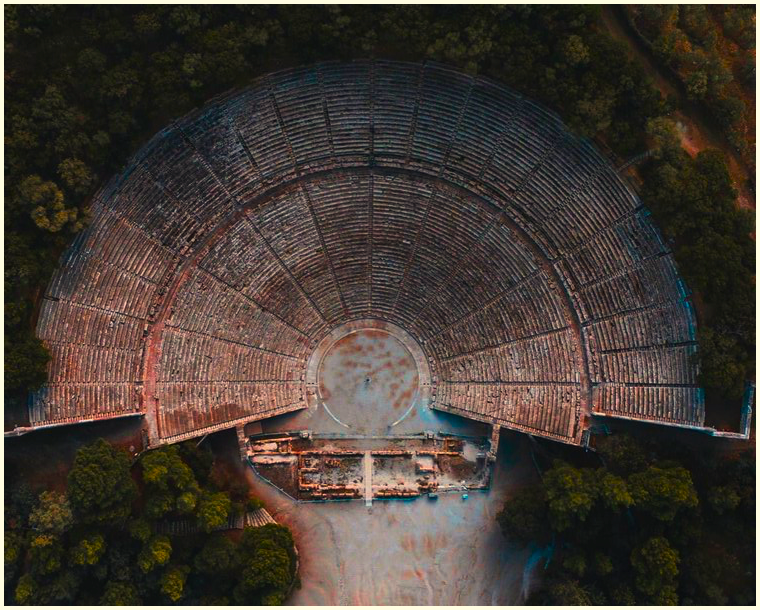

Theatre of Epidaurus (photo: Dimitrios Pallis, IG @pallisd)

You may be wondering what a blog post about an ancient Greek theatre and sanctuary has to do with a story set in ancient Rome.

Well, let me tell you, it has a lot to do with it. Not only was the healing sanctuary at ancient Epidaurus well-known in the Roman world, but the great theatre there also plays an important role in Sincerity is a Goddess. However, not in the way you might think.

Don’t worry though, for there are no spoilers if you haven’t read the book yet.

In this post, we’re going to be taking a brief look at the two faces of ancient Epidaurus – the theatre itself, and the sanctuary of Asklepios which was renowned across the ancient world for its healing…and snakes!

Let’s get into it!

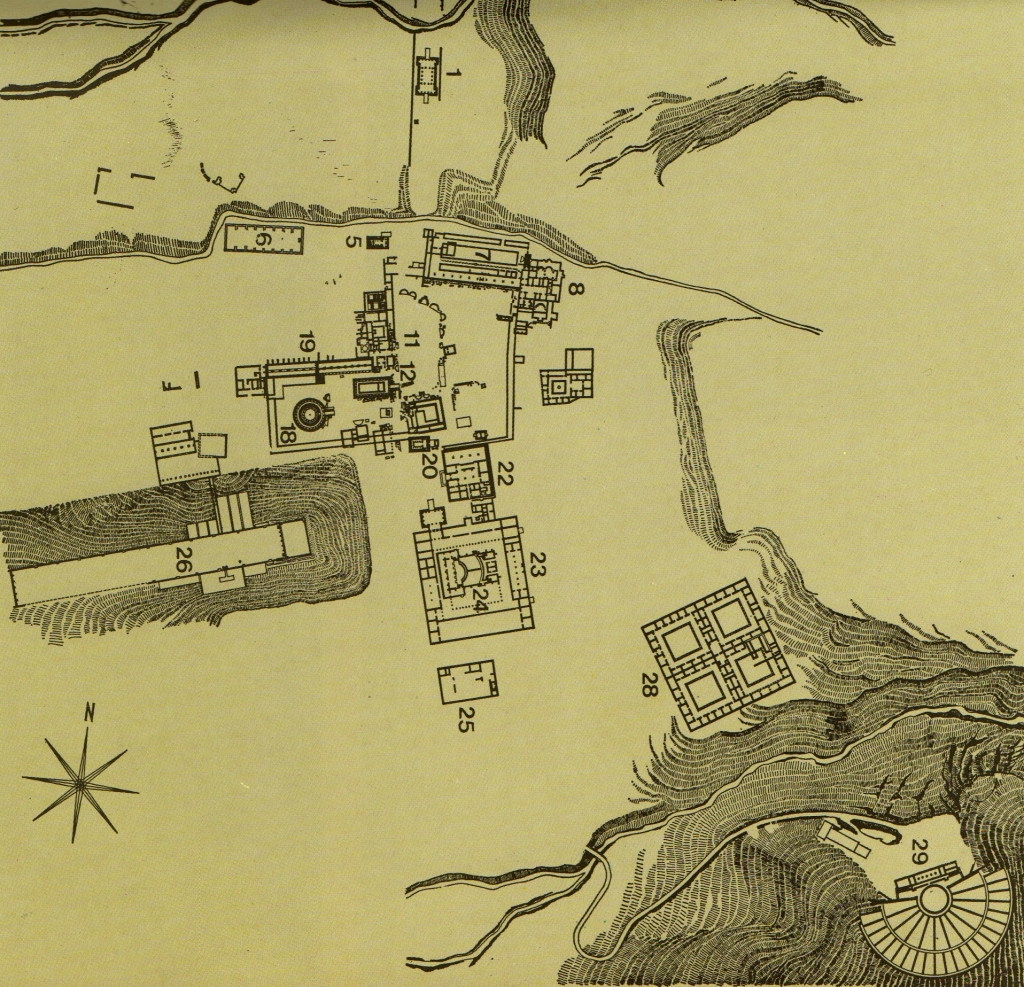

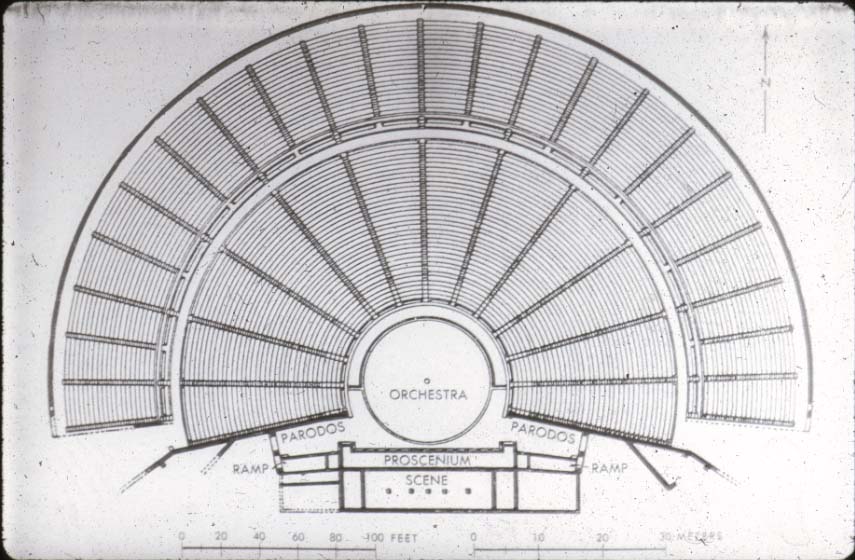

Plan of the Theatre of Epidaurus

Firstly, as Epidaurus is, today, famous for its well preserved odeon, and as Sincerity is a Goddess is partially a story about a theatre troupe, we’ll start with the theatre itself.

I’ve been to this site several times in the past, and I never tire of it. Some places are like that, I suppose. You can visit them again and again, and each time you do you get a different perspective that adds to your overall impression of the site.

The theatre of Epidaurus is like that.

For the history-lover in me, going there is like visiting a wise old friend. We greet each other, sit back in the sunshine, reminisce, and contemplate the world before us.

There is something comforting about going back to familiar places.

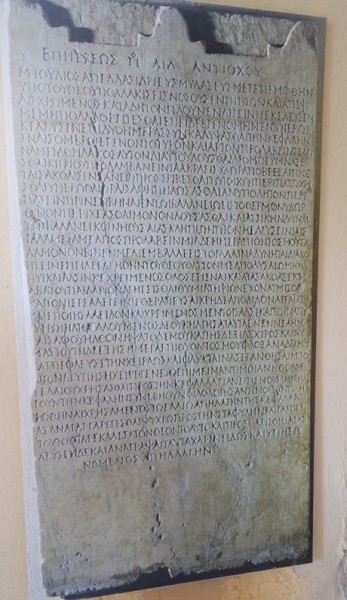

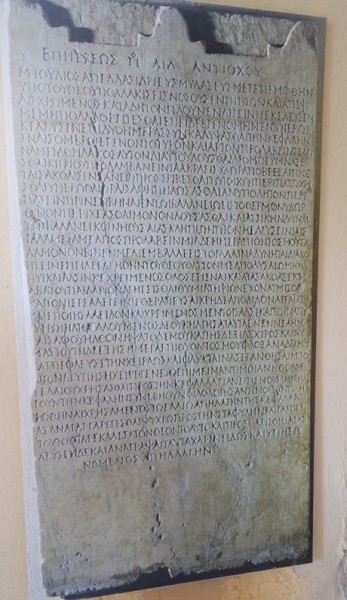

When you enter the archaeological site from the ticket booths and follow the path, you find the museum on your left, its wall lined with marble blocks covered in votive inscriptions from the sanctuary of Asklepios (more on that shortly).

I don’t know why, but every time we visit Epidaurus, I’m always drawn to the theatre first. Perhaps it is more familiar, simpler than the archaeological site of the sanctuary opposite? You walk up the steep stone steps beneath scented pine trees and then, there it is!

The theatre lies in the blinding sunlight all limestone and marble, rising up in perfect symmetry before you with the mountains beyond.

It’s always a shock to stand there and see it for the first time, this perfect titan, an ancient stage beneath a clear blue sky where the works of Euripides, Aeschylus, Aristophanes, Sophocles and so many more have entertained the masses and provoked thought in the minds of mortals for well over two thousand years.

In ancient times, one’s view from this vantage would have been partially blocked by the stage building, or scaena, but as it is today, you have a perfect view over the ruins of that building’s foundations.

Side entrance to the orchestra

The Epidaurians have a theatre within the sanctuary, in my opinion very well worth seeing. For while the Roman theatres are far superior to those anywhere else in their splendour, and the Arcadian theatre at Megalopolis is unequalled for size, what architect could seriously rival Polycleitus in symmetry and beauty? For it was Polycleitus who built both this theatre and the circular building.

(Pausanias, Description of Greece, 2.27.5)

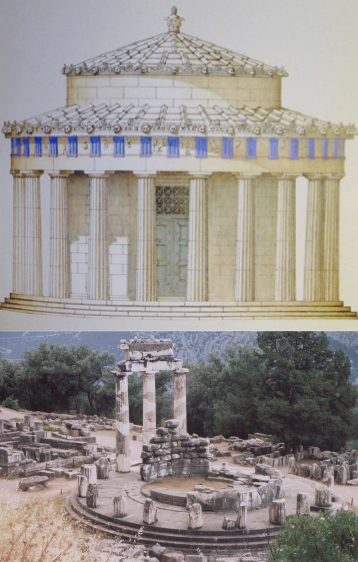

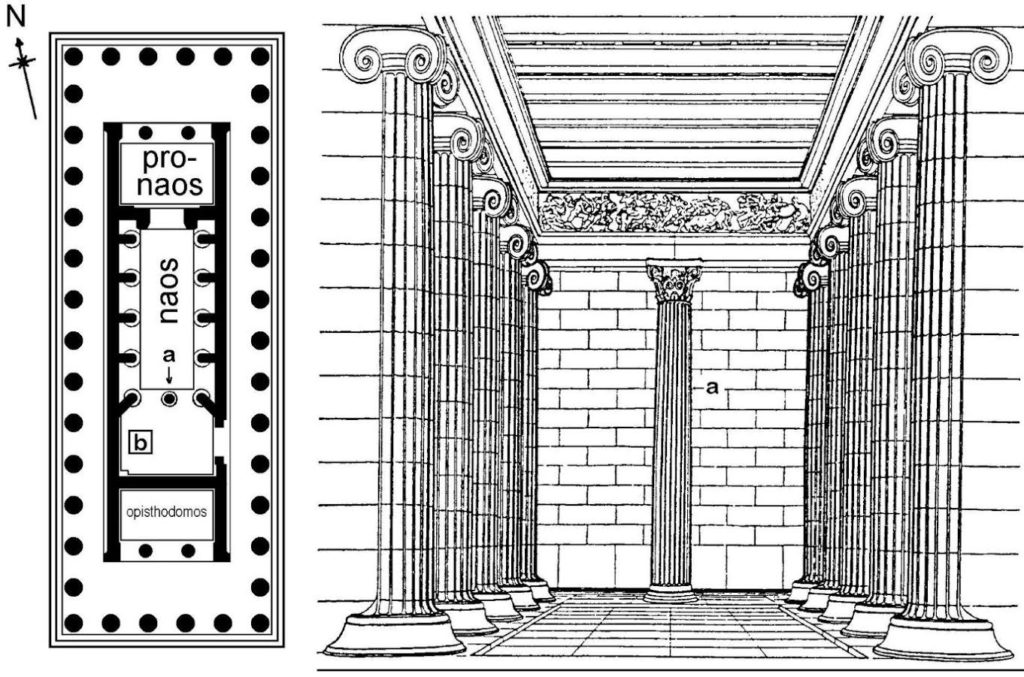

The theatre of Epidaurus is considered the best-constructed and most elegant theatre of the ancient world. It was built in the 4th century B.C by the sculptor and architect, Polykleitos the Younger, who also designed the tholos in the sanctuary nearby.

The theatre sat 14,000 spectators, and every one of them could see the stage and hear every momentous word that was spoken.

As people are wont to do when visiting this theatre, I’ve stood at the centre of the stage (the orchestra), and dropped a coin so that my family and friends could hear it where they sat at the top row.

Then I speak…

It is a surreal, dreamlike experience to do so, from that orchestra, for your voice is so loud in your ears, you can’t quite grasp what is happening at first. It feels like you are speaking into a microphone, your voice amplified. But there are, of course, no electronics, just an ancient perfection of design that has set the standard for ages.

You don’t want to tumble down this aisle!

I always climb the long central isle to the top row and sit down to take it all in. It’s a long way up, but the top provides the perfect vantage point of the sanctuary and landscape surrounding Epidaurus. I love to just sit there and listen to the cicadas, take in the view, and enjoy the dry, pine-scented air.

I’ve had the privilege of seeing Gerard Dépardieu perform in Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, and Isabella Rossellini in an adaptation of Stravinsky’s Persephone in the theatre of Epidaurus. It was amazing to watch such wonderful actors giving a performance there, and it was obvious too that they were enjoying the space, the tradition they were taking part in.

The last play I saw at Epidaurus was a performance of Aristophanes’ Lysistrata, a comedy in which the women of Greece withhold sex from all the men in order to put an end to the Peloponnesian War.

Isabella Rossellini in ‘Persephone’

When you see a play at Epidaurus, the audience is also participating in an ancient tradition. How many people have gone before us, sat in those seats, laughed and wept at the drama being played out before them?

It’s difficult not to think about that when you sit in the seats of Epidaurus. Whether you are basking in the hot rays of the Mediterranean sun, or waiting for a play to begin as the sun goes down and the stars appear, Centaurus and Cygnus twinkling in the sky above, one thing is certain – you will never forget the moments that you spend there.

Next, we’re going to venture away from the theatre for a brief visit to the museum, and then on into the peace and quiet of the Sanctuary of Asklepios, a place of miracles and ancient healing that was famous across the Greek and Roman worlds.

Looking north from the theatre to the sanctuary

When you enter the abode of the god

Which smells of incense, you must be pure

And thought is pure when you think with piety

This is the inscription that greeted pilgrims who passed through the propylaia, the main gate to the north, into the sanctuary of the god, Asklepios, at ancient Epidaurus.

The ancient writer, Pausanias, gives us some interesting insights…

The sacred grove of Asclepius is surrounded on all sides by boundary marks. No death or birth takes place within the enclosure. The same custom prevails also in the island of Delos. All the offerings, whether the offerer be one of the Epidaurians themselves or a stranger, are entirely consumed within the bounds.

(Pausanias, Description of Greece, 2.27.1)

After the glory of the ancient theatre, it feels like something of a contrast to step into the quiet realm of the sanctuary of the God of Healing. This was a place that was famous around the ancient world for the miracles of health and healing that occurred there.

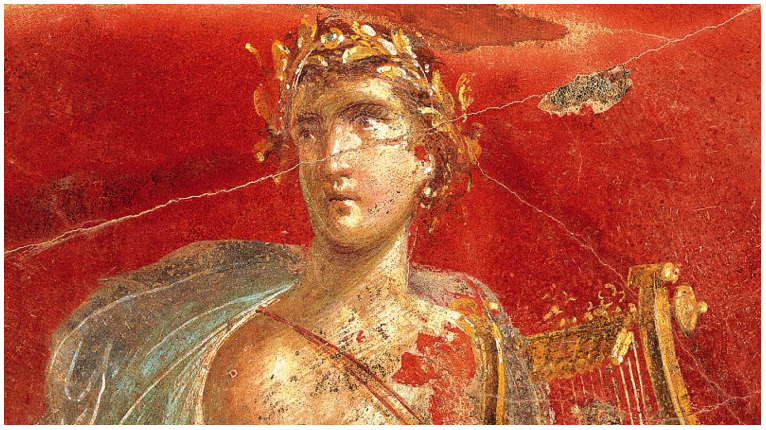

But perhaps the contrast is not so great? After all, Asklepios was the son of Apollo – an interesting union of healing and art – and it could be argued that the experiences one had in the theatre and the sanctuary were both transformative and healing.

Toward the back of the sanctuary there is a small, but wonderful, site museum that is well worth a visit for the collection of architectural and everyday artifacts.

The vestibule contains cabinets filled with oil lamps, containers and phials that were used for medicines and ointments within the sanctuary, as well as surgical implements and votive offerings.

Medical Instruments in the Epidaurus museum

Above the cabinets and into the main room of the museum, there are reliefs and cornices from the temple of Asklepios decorated with lion heads, acanthus and meander designs, many of which still have the original paint on them.

However, in the first part of the museum are some plain-looking stele that are covered in inscriptions recording the remedies given at Epidaurus, and the miracles of healing at the sanctuary in ancient times. These inscriptions are where much of our knowledge of the sanctuary comes from.

Stele with accounts of healing at the sanctuary, as well as quotes of the Hymn to Apollo

In the main part of the museum, your eyes are drawn, once more, to the magnificent remains of the tholos and the temple of Asklepios – ornate Corinthian capitals, cornices decorated with lion heads, and the elaborately-carved roof sections of the temple’s cella, the inner sanctum.

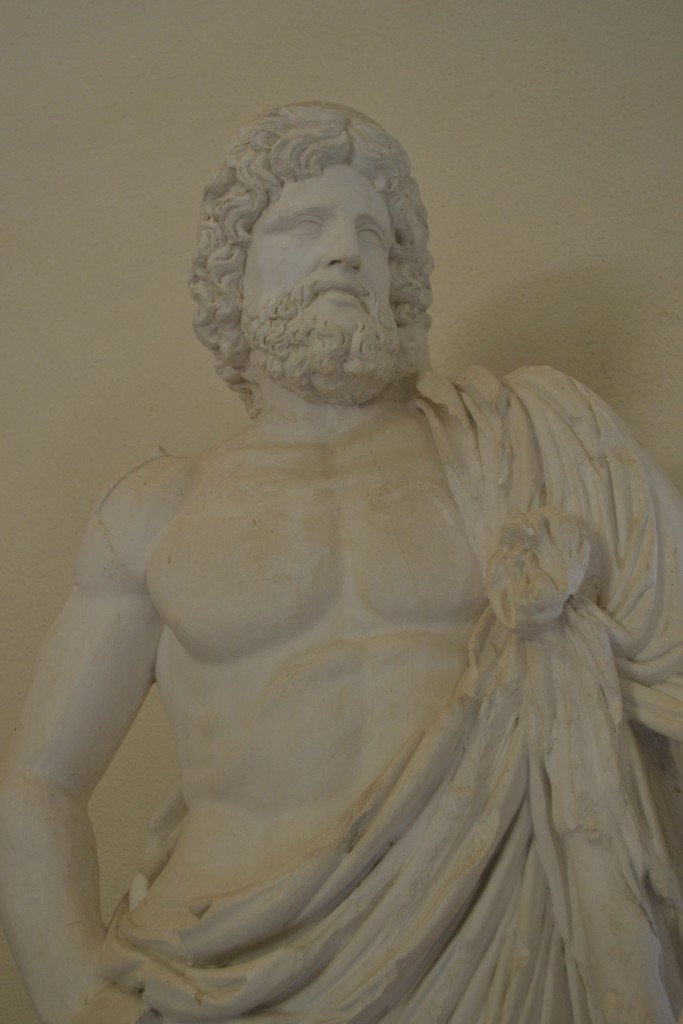

There are statues of Athena and Asklepios that had adorned various parts of the sanctuary, and the winged Nikes that stood high above pilgrims, gazing out from the corners of the roof of the temple of Artemis, the second largest temple of the sanctuary.

The Museum Interior

I wonder if people walking through the museum realize how beautiful the statues are, the meaning they held for those who came to the sanctuary in search of help?

After one cools off in the museum, it’s time to head for the sanctuary of Asklepios just north of the museum and theatre.

Every time I’ve visited, the sanctuary itself is usually completely empty.

It seems that most visitors head for the theatre alone, some to the museum afterward, but most do not want to tough it out among the ruins of one of the most famous sanctuaries in the ancient world.

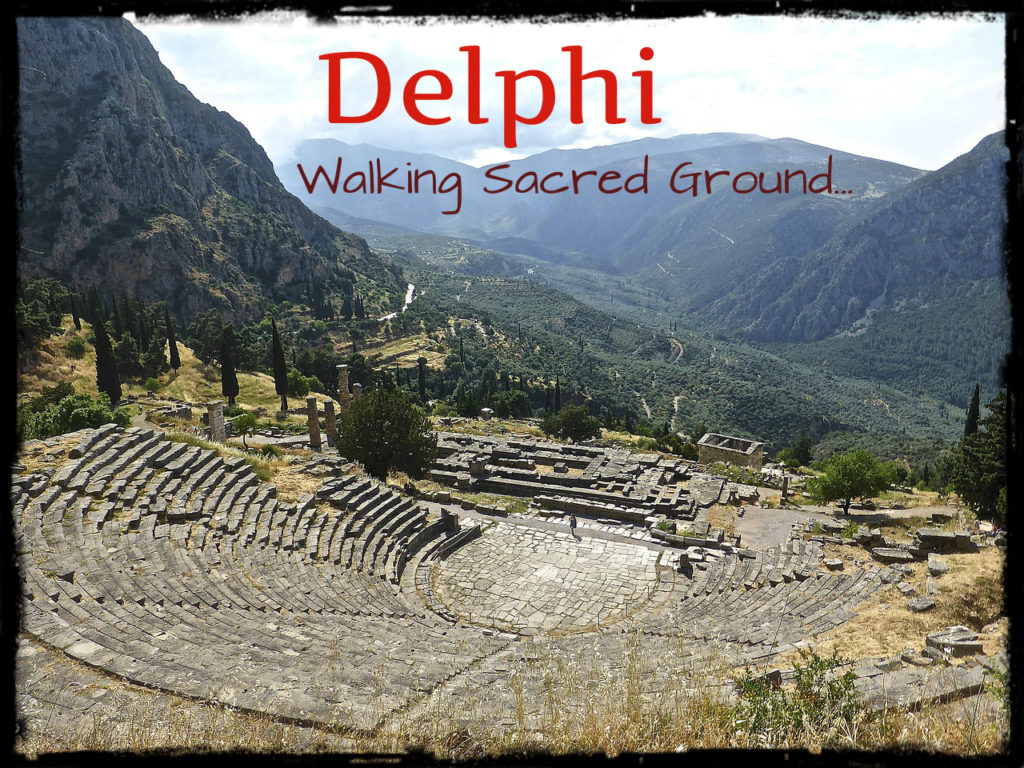

The Sanctuary of Asklepios from the North

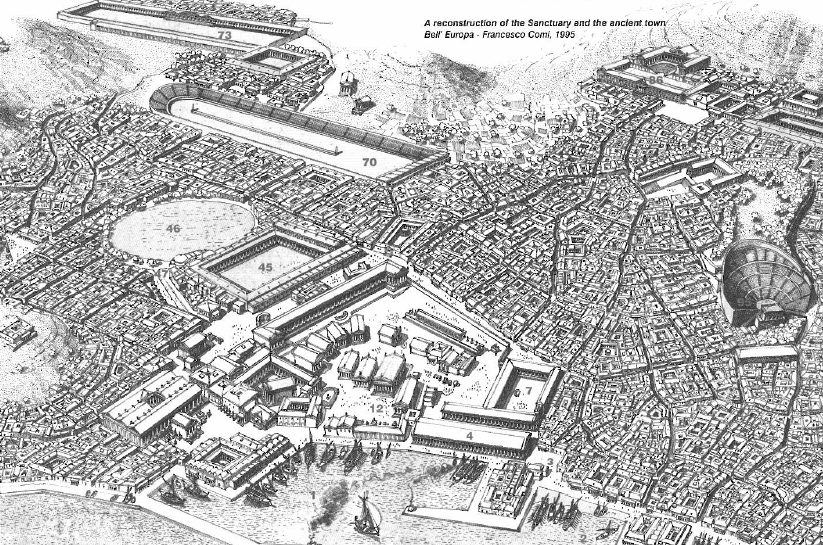

The Sanctuary of Asklepios lies on the Argolid plain, with Mt. Arachnaio and Mr. Titthion to the north. The former was said to have been a home of Zeus and Hera, and the latter, whose gentle slopes lead down to the plain, was said to have been where Asklepios was born.

To the south of the sanctuary is Mt. Kynortion, where there was a shrine to Apollo, Asklepios’ father. Farther to the south are the wooded slopes of Mt. Koryphaia, where the goddess Artemis is said to have wandered.

This is a land of myth and legend, a world of peace and healing, green and mild, dotted with springs. The sanctuary was actually called ‘the sacred grove’.

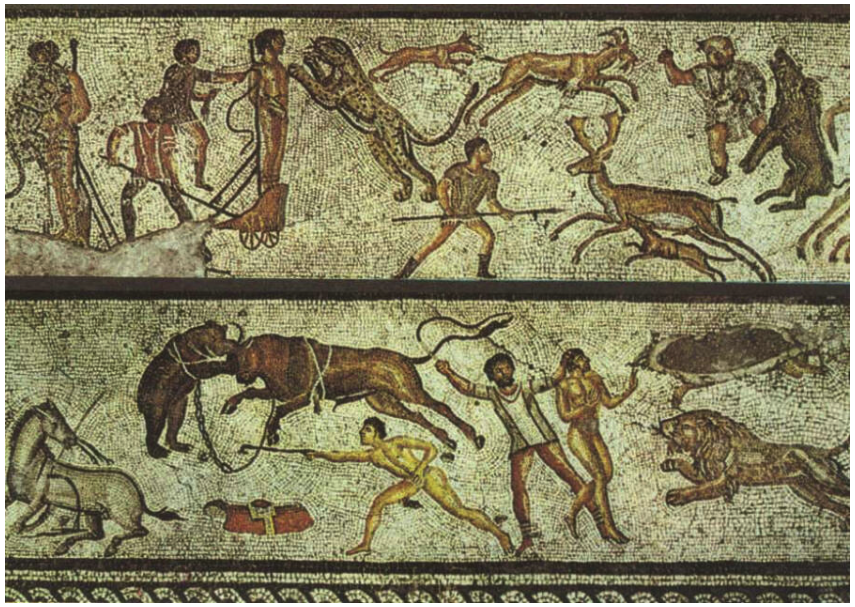

Asklepios, as a god of healing, was worshiped at Epidaurus from the 5th century B.C. to the 4th century A.D. According to archaeologist Angeliki Charitsonidou, it was the sick who turned to Asklepios, people who had lost all hope of recovery – the blind, the lame, the paralyzed, the dumb, the wounded, the sterile – all of them wanting a miracle.

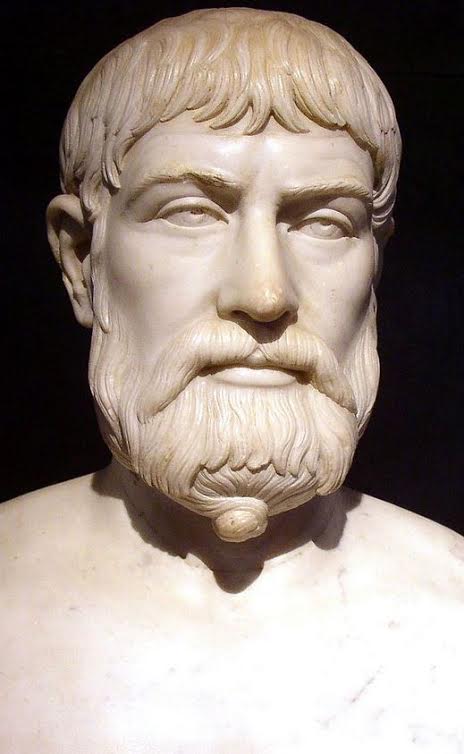

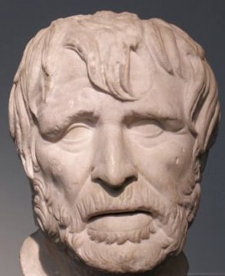

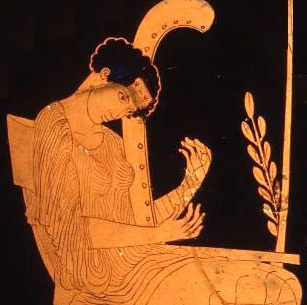

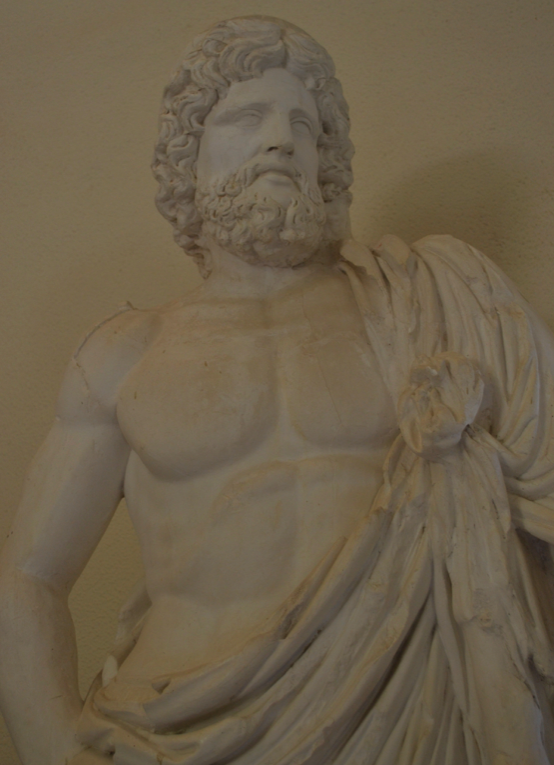

Asklepios

But who was Asklepios?

Some believed he learned medicine from the famous centaur, Cheiron, in Thessaly. Another tale from the Homeric age makes Asklepios a mortal man, a king of Thessaly, whose sons Machaon and Podaleirios fought in the Trojan War and learned medicine from their father.

Eventually, it came to be believed that Asklepios was a demigod, born of a union between Apollo and a mortal woman. His father was also a god of healing, and prophecy and healing, in the ancient world, went hand-in-hand. The snake was a prophetic creature, and a creature of healing, so it is no wonder this animal came to be associated with Asklepios and medicine.

At Epidaurus, snakes were regarded as sacred, as a daemonic force used in healing at the sanctuary. These small, tame, blondish snakes were so revered that Roman emperors would send for them when in need. Once again, Pausanias gives us some insight:

The serpents, including a peculiar kind of a yellowish colour, are considered sacred to Asklepios, and are tame with men. These are peculiar to Epidauria, and I have noticed that other lands have their peculiar animals. For in Libya only are to be found land crocodiles at least two cubits long; from India alone are brought, among other creatures, parrots. But the big snakes that grow to more than thirty cubits, such as are found in India and in Libya, are said by the Epidaurians not to be serpents, but some other kind of creature.

(Pausanias, Description of Greece, 2.28.1)

Now you know where this symbol comes from!

I’ll stick with the tame blond snakes, thank you very much!

The thing about Asklepios was that he was said to know the secret of death, that he had the ability to reverse it because he was born of his own mother’s death. Zeus, as king of the gods, believed that this went against the natural order, and so he killed Asklepios with a bolt of lightning.

There are no written records of medical interventions by the priests of Epidaurus in the early centuries of its existence. The healing that occurred was only through the appearance of the god himself. However, over time the priesthood of Epidaurus began to question patients about their ailments, and prescribe routines of healing or exercise that would carry out the instructions given to pilgrims by Asklepios in the all-important dreams, the enkoimesis, which they had in the abato of the sanctuary.

It is quite a feeling to walk the grounds of the sanctuary at Epidaurus, to be in a place where people believed they had been touched or aided by a god, and actual miracles had occurred and were recorded.

Faith and the Gods are a big part of ancient history, and cannot be separated from the everyday. I’ve always found that I get much more out of a site, a better connection, when I keep that in mind. You have to remove the goggles of hindsight and modern doubt to understand the ancient world and its people.

From the museum you walk past the ruins of the hospice, or the ‘Great Lodge’, a massive square building that was 76 meters on each side, two-storied, and contained rooms around four courtyards. This is where later pilgrims and visitors to the sanctuary, and the games that were held in the stadium there, would stay.

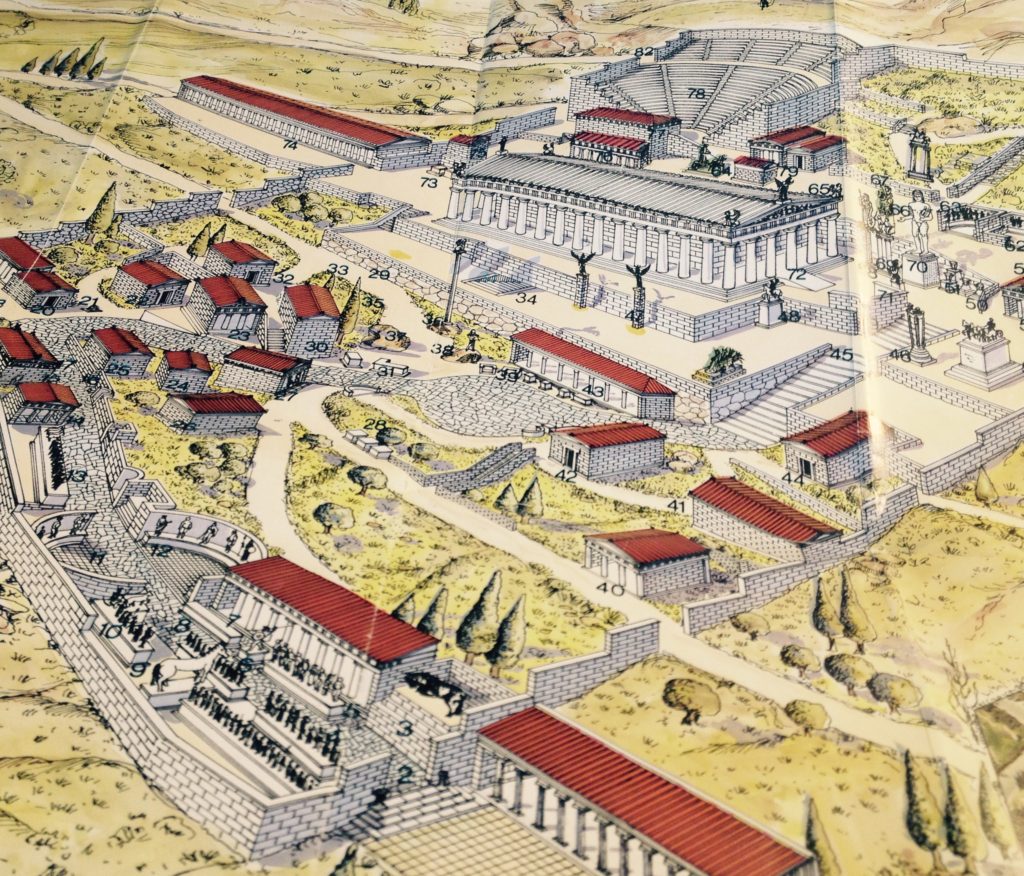

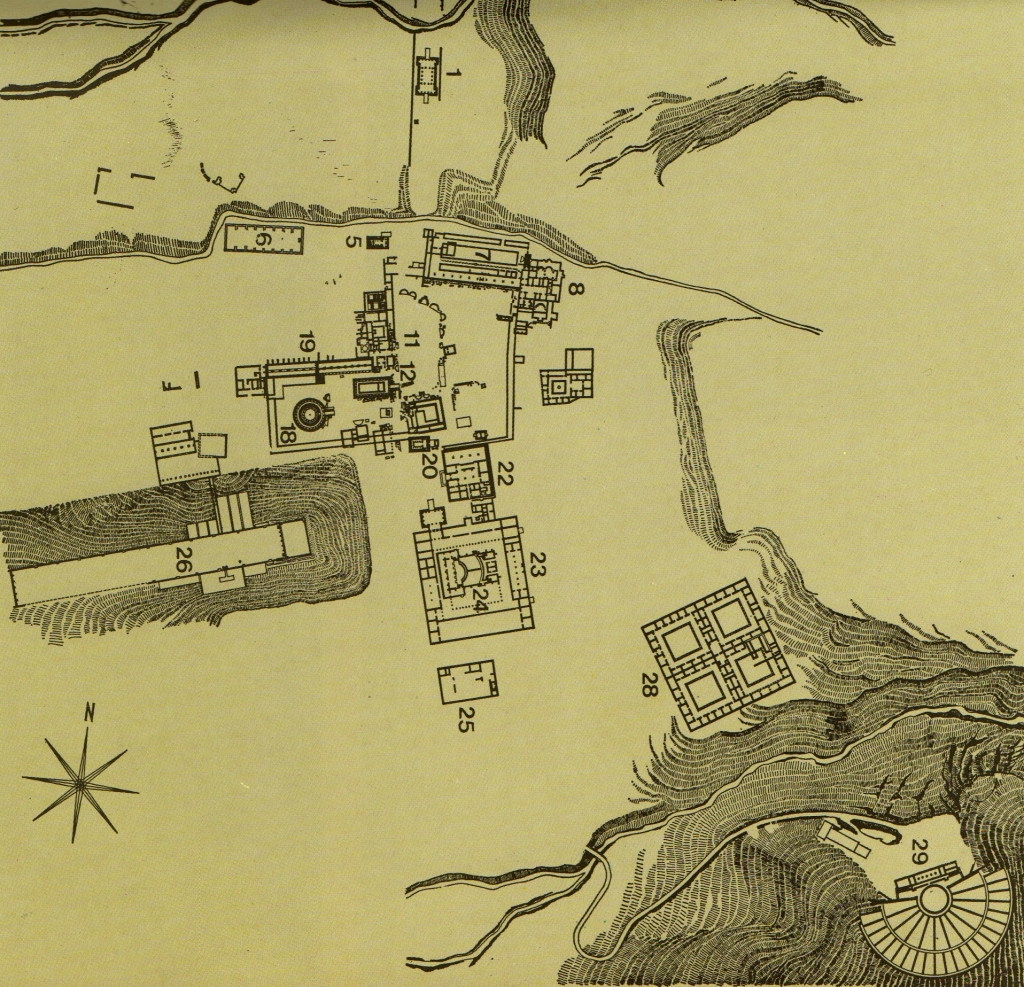

Map of the Sanctuary (from the site guide book)

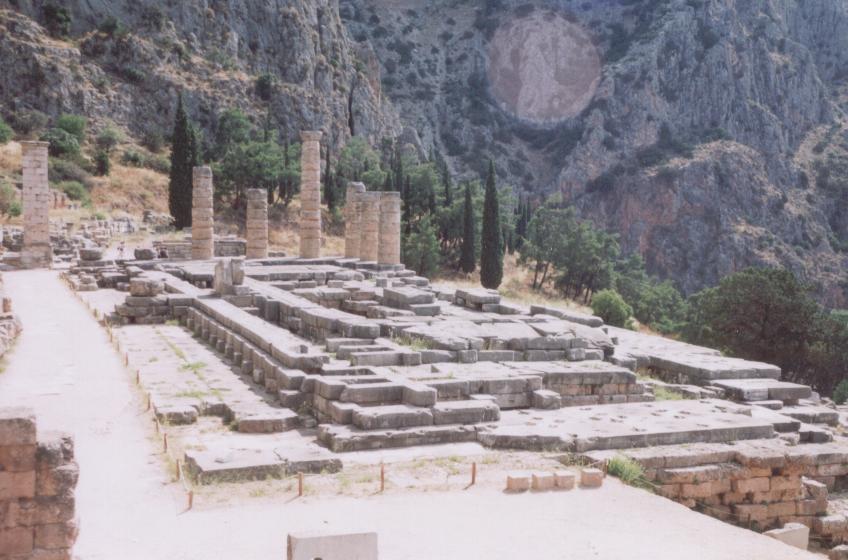

Without a map of what you are looking at, it’s difficult to pick out the various structures. Most of the remains are rubble with only the foundations visible. This sanctuary was packed with buildings, and apart from a few bath houses, a palaestra, a gymnasium, a Roman odeion, the stadium and a large stoa, there are some ruins that one is drawn to, notably the temples.

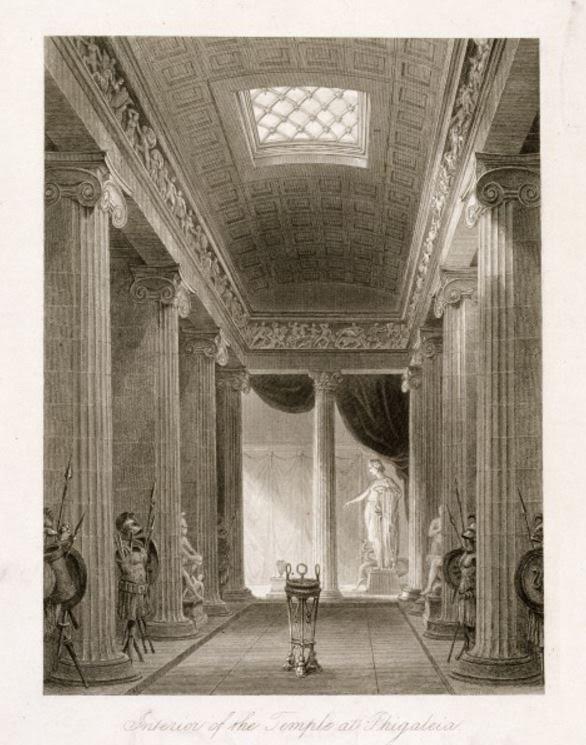

The sanctuary of Asklepios has several temples the largest being dedicated to the God of Healing himself, within which there stood a large chryselephantine statue of Asklepios.

There were also temples to Artemis (the second largest on-site), Aphrodite, Themis, Apollo and Asklepios of Egypt (a Roman addition), and the Epidoteio which was a shrine to the divinities Hypnos (sleep), Oneiros (Dream), and Hygeia (Health). These latter divinities were key to the healing process at Epidaurus.

Ancient Epidaurus was a sacred escape where the mind, body, and soul could recuperate. It is a place of sunlight and heat, of fresh air and green trees set against a backdrop of mountains tinged with salt from the not-too-distant sea. Cicadas yammer on in a bucolic frenzy, and bees and butterflies wend their way among the fallen pieces of the ancient world as your feet crunch along on the gravel pathway, past the ruins of the palaestra, gymnasium, and odeion to an intersection in the sacred precinct of the sanctuary.

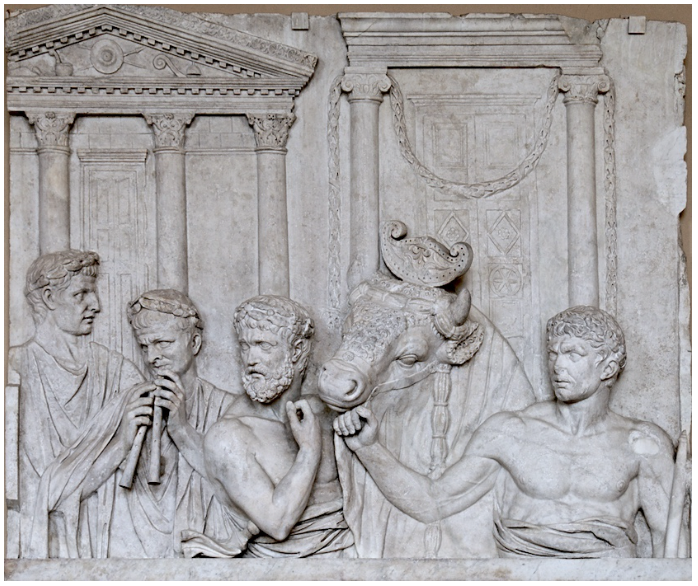

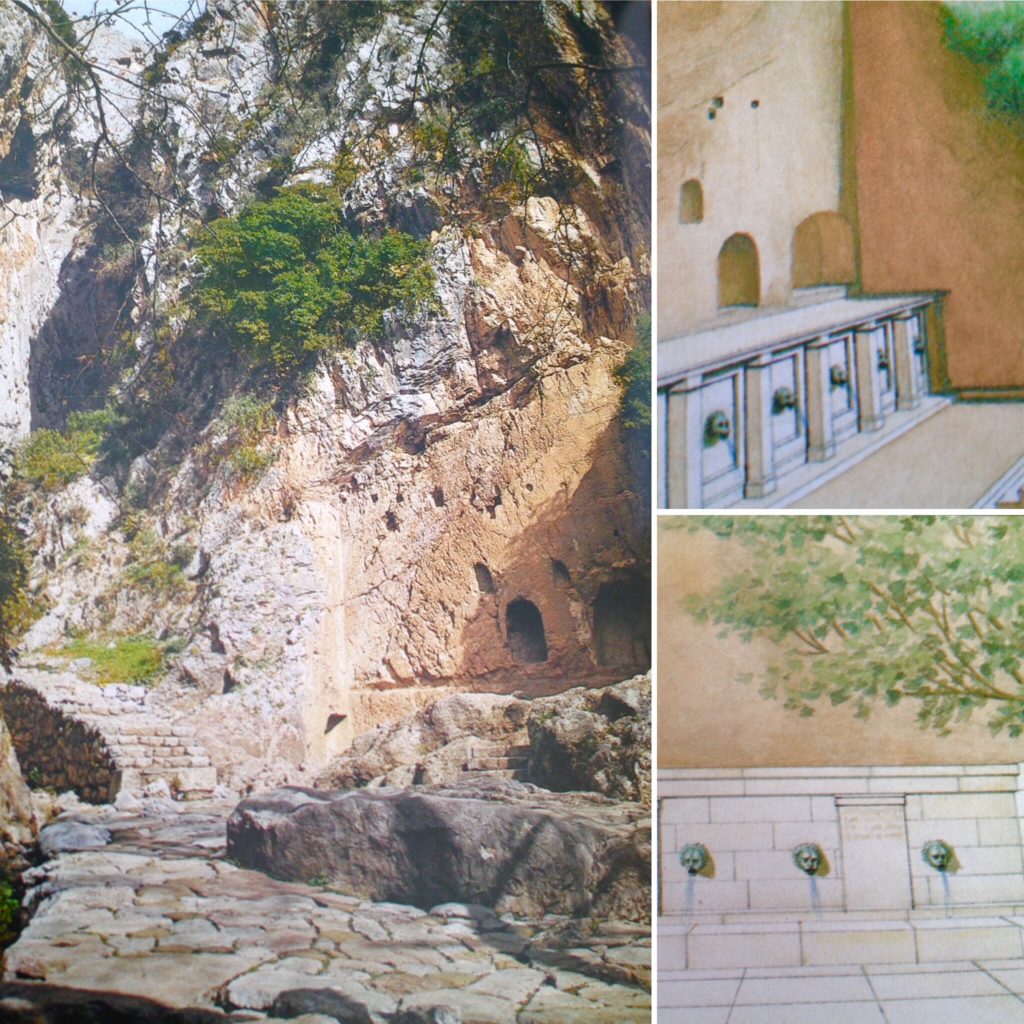

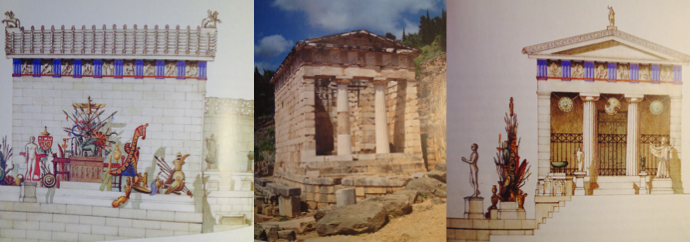

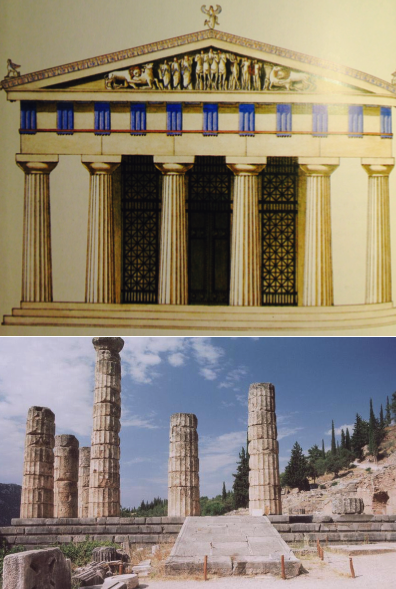

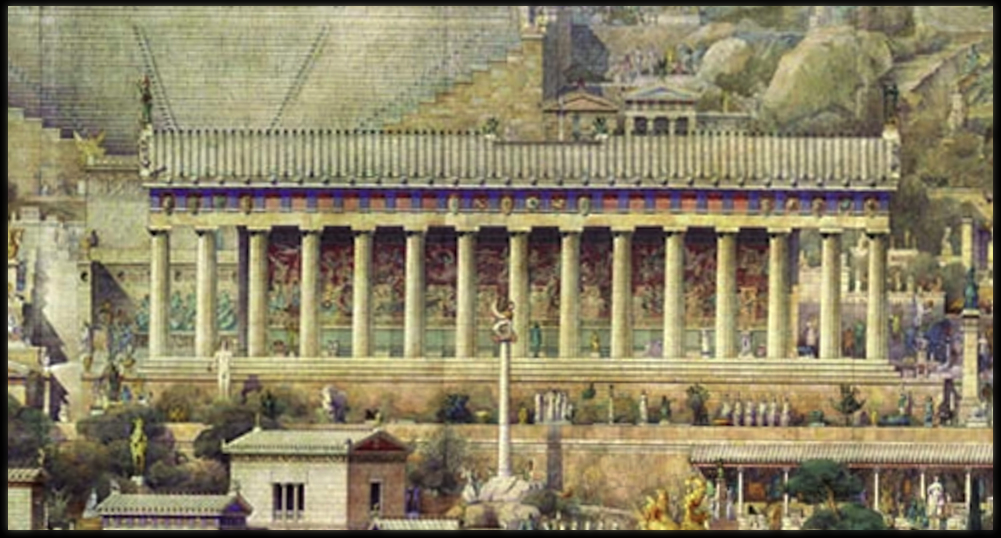

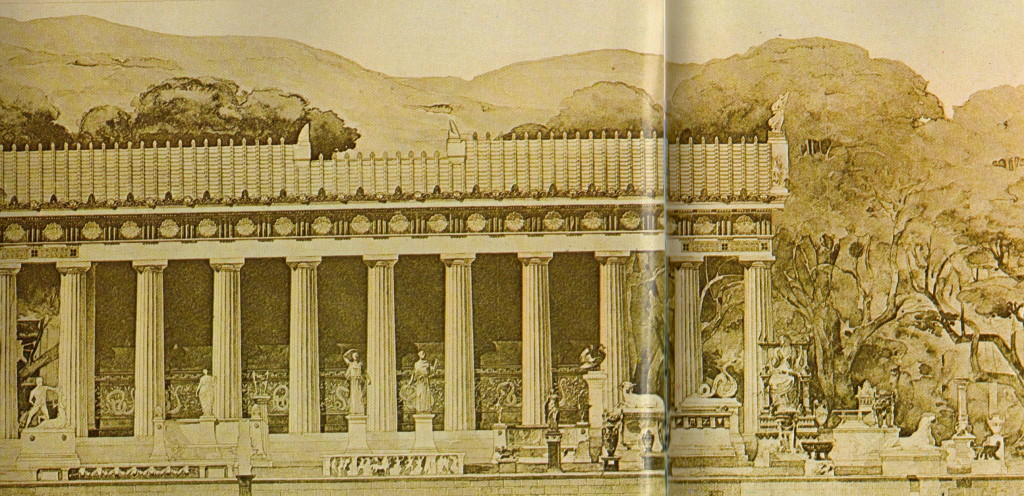

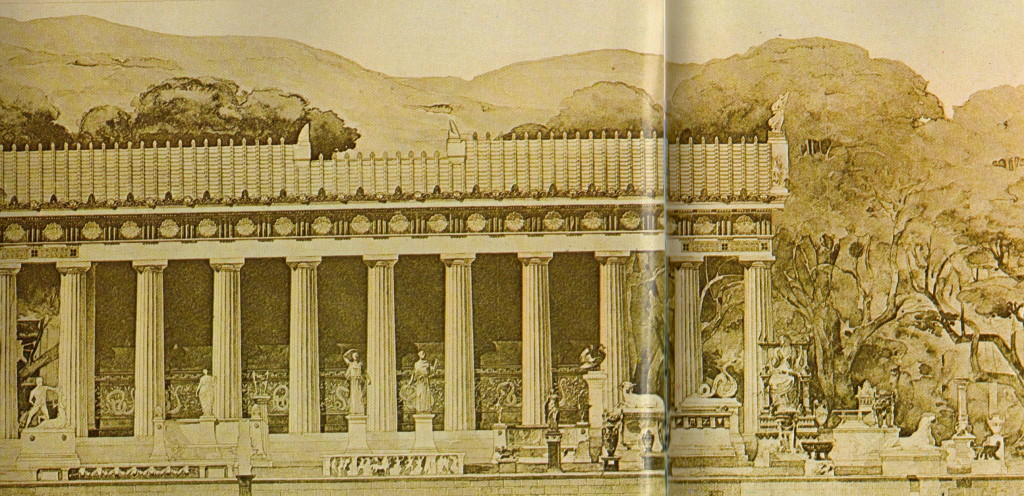

Reconstruction of the Temple of Asklepios’ south side (from site guide book)

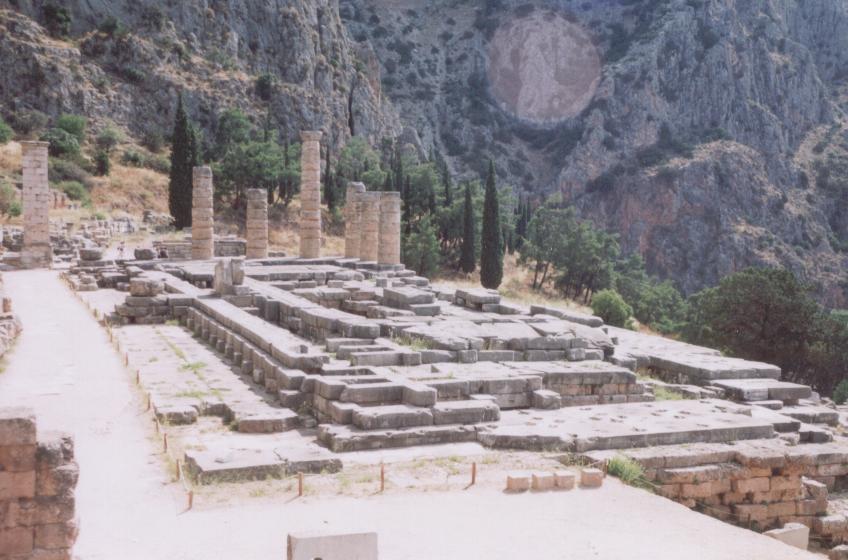

Here you find the temple of Artemis to your right as you face the ruins of what was the magnificent temple of Asklepios to the north. You can see the foundations, the steps leading up.

The image of Asklepios is, in size, half as big as the Olympian Zeus at Athens, and is made of ivory and gold. An inscription tells us that the artist was Thrasymedes, a Parian, son of Arignotus. The god is sitting on a seat grasping a staff; the other hand he is holding above the head of the serpent; there is also a figure of a dog lying by his side. On the seat are wrought in relief the exploits of Argive heroes, that of Bellerophon against the Chimaera, and Perseus, who has cut off the head of Medusa.

(Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2.27.2)

It is interesting that in a place where dreams were part of healing, the images carved on the seat of Asklepios portray some of the greatest heroes fighting and defeating their own ‘monsters’.

How many people in need had walked, limped or crawled up those steps seeking the god’s favour.

On your left you see a large, flat area of worn marble that was once the great altar of Apollo where pilgrims made blood sacrifices to Apollo and Asklepios in the form of oxen or cockerels, or bloodless offerings like fruit, flowers, or money.

Remains of the Great Altar of Apollo

Standing there, you can imagine the scene – smoke wafting out of the surrounding temples with the strong smell of incense, the slow drip of blood down the sides of the great altar, the tender laying of herbs and flowers upon the white marble, all in the hopes of healing.

As people would have stood at the great altar, they would have seen one of the key structures of the sanctuary beyond it, just to the west – the tholos.

The tholos was a round temple that was believed to be the dwelling place of Asklepios himself. It was here that, after a ritual purification with water from the sanctuary, that pilgrims underwent some sort of religious ordeal underground in the narrow corridors of a labyrinth that lay beneath the floor of the tholos’ cella, the inner sanctum.

Reconstruction of Epidaurian Tholos and Temple of Asklepios (photo reconstruction: CNN)

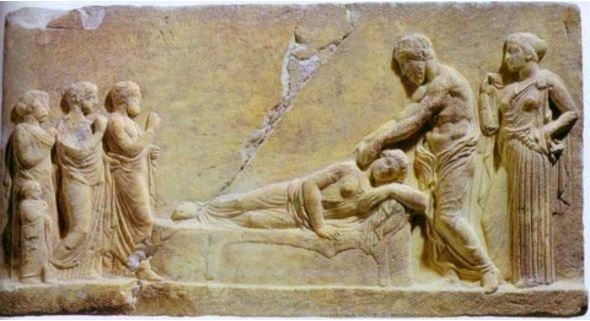

After their ritual ordeal, pilgrims would be led to the abato, a long rectangular building to the north of the tholos and temple of Asklepios.

The abato is where pilgrims’ souls would be tested by way of the enkoimesis, a curative dream that they had while spending the night in the abato.

Miracles happened in this place, and there are over 70 recorded inscriptions that have survived which detail some of them – mute children suddenly being able to speak, sterile women conceiving after their visit to sanctuary, a boy covered in blemishes that went away after carrying out the treatment given to him by Asklepios in a dream. There are many such stories that have survived, and probably many that we do not know of.

Inside the partially restored Abato

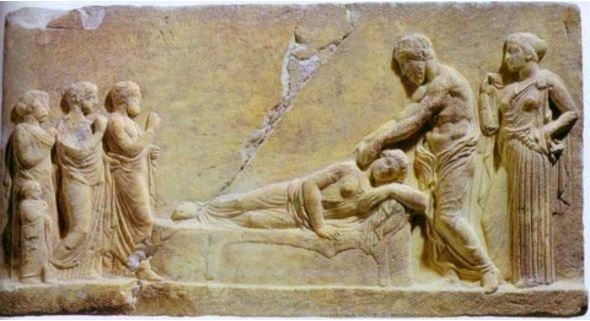

As you stand in the abato, careful not to step on any snakes that may be hiding along the base of the walls, it’s a time to reflect on the examples of healing on the posted placard. It seemed that the common thread to all the dreams that patients had was that Asklepios visited them in their dreams and, either touched them, or prescribed a treatment which subsequently worked.

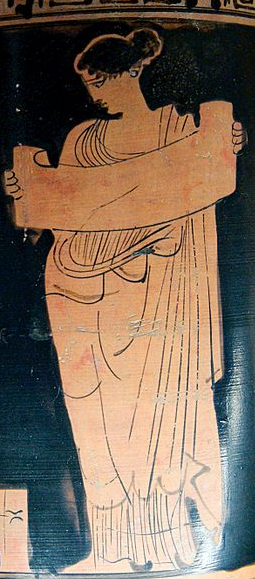

Relief of Asklepios healing a dreamer

Sleep. Dream. Health.

When I think of those divinities who were also worshiped at Epidaurus, right alongside Asklepios, it doesn’t seem so far-fetched. In fact, standing there, in that place of peace and tranquility, it seems highly likely.

The people mentioned on the votive inscriptions – those who left vases, bronzes, statues, altars, buildings and fountains as thank offerings to the god and his sanctuary for the help they received – those people were real, as real as you and me. They confronted sickness, disease, and worry, just as we do.

Today, some people turn to their chosen god for help when they are in despair. Others turn to the medical professionals whom they hope have the skill and compassion to cure them.

At ancient Epidaurus, people could get help from both gods and skilled healers, each one dependent on and respectful of the other.

This place haunts me in a way. I always think about how special this place is, how the voices of Epidaurus, its sanctuary, and its great theatre, will never die or fade.

Indeed, just as Asklepios was said to have done, this is a place that defies death and time.

Remains of Temple of Asklepios

It is indeed fitting that the theatre and sanctuary go together, for both are healing experiences, forcing the mortal attendees to look inward, to delve into the darker depths of their selves to observe their own trials and tribulations so that they can manage their healing.

Theatre is a transformative experience, and so it and the healing sanctuary both deserve their places beside each other, as well they do in the pages of Sincerity is a Goddess.

Thank you for reading.

Sincerity is a Goddess is now available in ebook, paperback and hardcover from all major online retailers, independent bookstores, brick and mortal chains, and your local public library.

CLICK HERE to buy a copy and get ISBN#s information for the edition of your choice.