Few things about the ancient Roman world fascinate the modern masses more than gladiators. The subject of slaves dueling to the death for the entertainment of the mob is horrible, but at the same time darkly entertaining.

In the popular mind, most of what we imagine gladiators and gladiatorial combat to have been comes from popular movies and television. I still remember the first time I watched Spartacus as a kid, and the horror of the scene when Kirk Douglas fights his fellow gladiator, Draba (played by Woody Strode) and how the latter is cut down when he refuses to kill Spartacus. It made my heart race and guts tighten. A lasting impression to be sure!

And who can forget the more recent film, Gladiator, by Ridley Scott, with its epic fight scenes and recreation of the Flavian Amphitheatre, or rather, the Colosseum? Classics enrollment shot through the roof after that movie! What about the television series, Spartacus: Blood and Sand?

Bloody, brutal, entertaining and mesmerizing.

Are you not entertained!

(Sorry, I couldn’t help myself there. Love this movie!)

Apart from Spartacus: Blood and Sand, however, few attempts have been made to properly portray gladiators and their equipment, their styles. The focus in the media has been on death and the panem et circenses, or ‘bread and circuses’, aspect of it all.

In this post, we’re going to look at the various styles of gladiators, along with some of their weapons. The reality of gladiatorial combat in the major arenas of the Roman Empire was not of two half-naked men slashing away at each other, but rather of a highly organized blood sport with its own set of rules.

But before we delve into that, let’s take a brief look at the origins of gladiatorial combat.

Funeral Games were an ancient tradition. The Games in honour of the death of Patroclus beneath the walls of Troy are depicted here.

Originally, it’s thought that gladiatorial contests were not for entertainment, but rather for funeral games.

Possibly the oldest depiction of a gladiatorial contest comes from a tomb painting at Paestum, in Campania, around 370-340 B.C. The murals of this tomb portray various activities such as chariot races, fist fights, and a dual between armed men bearing, helmets, shields, and spears. A referee and three pairs of fighting men are also depicted.

Because of this find, and the presence of the oldest stone amphitheatres in the region, it has been argued that Campania is where gladiatorial fights originated. The region was also home to some of the most important gladiatorial schools, or ludi.

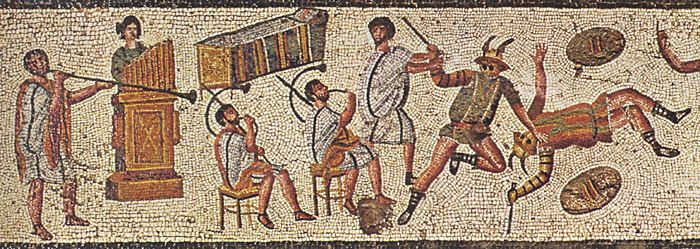

Some of the earliest known representations of gladiatorial combat from Campania, Italy.

The idea of shedding blood by a dead person’s grave, was an ancient tradition, and the Roman world was no stranger to blood sacrifice. You can read more about sacrifices in the Roman world HERE.

However, later Roman writers, such as the Christian writer, Tertullian (c. A.D. 200), frowned upon this particular rite of sacrifice:

For of old, in the belief that the souls of the dead are propitiated with human blood, they used at funerals to sacrifice captives or slaves of poor value whom they bought. Afterwards, it seemed good to obscure their impiety by making it a pleasure. So they found comfort for death in murder. (Tertullian, De Spectaculis 12)

Tertullian, in a way, displayed a mindset more in tune with our own, perhaps, in which most of us feel horror at the thought of public execution and torture. This is a modern mindset, however. When it came to early gladiatorial combat, it does indeed appear that life was cheap when it came to the first gladiators who were most likely prisoners of war and slaves.

Relief depicting gladiators

Over time, gladiatorial combat moved from being a rite for funeral games, to an entertainment for the masses. ‘Bread and circuses’ as Juvenal put it in the second century A.D.

With the growing popularity of gladiatorial combat, the aristocratic families who wanted to maintain their political power in Rome began to use the games as a means of securing their power. They did this by putting on public games for the masses, the mob. It became an expensive entertainment to put on, and also a part of everyday life in the Roman world.

The first public gladiator fight was apparently in the Forum Boarium, but later they occurred in the Forum Romanum, and then, once it was built, found a permanent home in the Colosseum.

Graffiti in Pompeii depicting two known gladiators

Gladiatorial contests grew in popularity, and these slaves, for that is what they were, came to be superstars, second only, you might say, to charioteers.

Though the Romans may not have invented gladiatorial combat, they do appear to have ‘perfected’ it. They developed ludi, gladiatorial schools run by a lanista. In the Roman Empire, the state came to exert a level of control – there were four imperial ludi in Rome itself! There were styles of gladiator with specialized weapons and training, diet and the best medical care. And gladiators were no longer just prisoners of war or slaves, but also criminals and even volunteers!

Gladiators were also an investment. They developed a market value depending on their successes. Gladiators were to ancient Rome, what our modern-day sports superstars are now. They were part of a great show, complete with stage sets and storylines. They even had stage names, their images popping up in scrawled graffiti all over Rome, etched by their adoring fans.

Mosaic depicting gladiators with their stage names. Note the theta symbol (a circle with a line) beside some which stands for ‘Thanatos’, indicating that they are dead.

At this point, you get the picture. Gladiators evolved from being a sacrifice, to superstars in the world of Roman blood sport.

However, it wasn’t just a matter of matching any type of gladiator against another. There were specific styles that developed over time, and they stemmed from mythological beasts to shadows of Rome’s former enemies.

Pairings of the different types of gladiators were not random. You might be surprised to know that the rules called for very specific types of gladiators to be pitted against each other, especially in the great amphitheatres of the Empire.

Much of what we know of the equipment of the different types of fighters comes from pictorial depictions on anything from elaborate mosaics, to frescos, oil lamps and even street graffiti.

An ancient oil lamp decorated with a gladiatorial combat scene. The perfect addition to any young man’s cubiculum!

The different classes of gladiators had distinctive equipment, and protection was worn on different parts of the body, depending on the style. Usually, the head, face and throat were protected by a helmet, and some of these are the most impressive remains of gladiatorial equipment. Different limbs were also protected by organic materials like leather and linen, but there were also metal guards such as greaves.

In almost all cases, the gladiator’s chest, no matter the style, was unprotected, but for the provocator which we will look at shortly. The only piece of clothing worn was a loin cloth, or subligaculum, which was belted with a cingulum or later, a wide sash.

There were variations on some of the protective equipment such as manicae, which were arm guards worn regularly in late antiquity, and fasciae, padded tubes for the legs which could be worn beneath greaves.

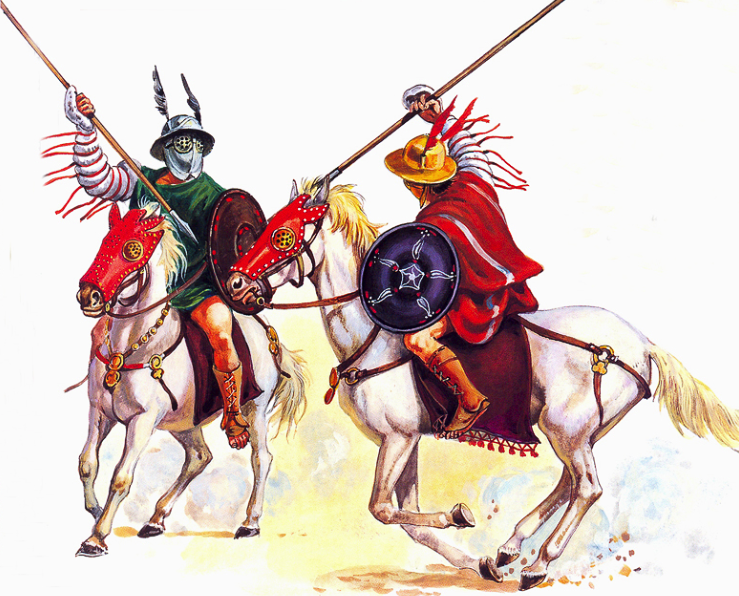

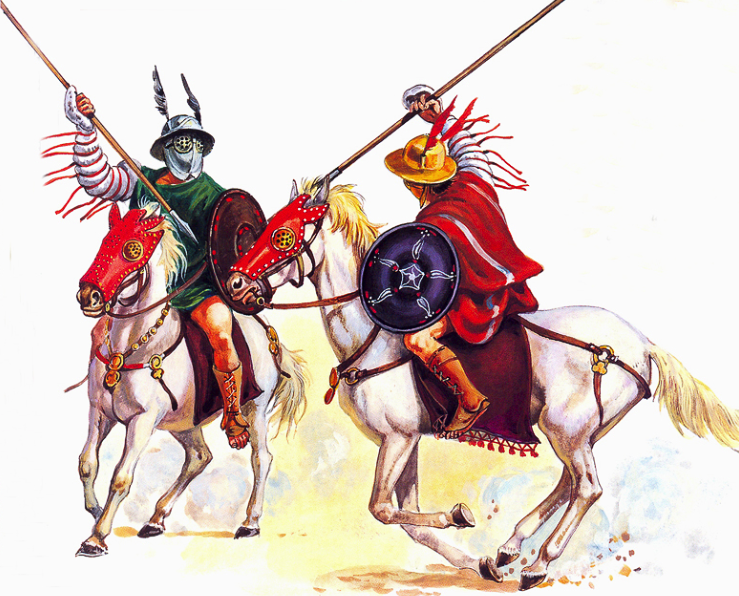

Artist impression of two equites gladiators

The first type of gladiator we are going to look at is the eques, or horseman.

Equites fought only against other equites, and were considered lightly-armed gladiators. They were the only gladiators to wear clothing, in the form of a tunica, and they wore gaiters on their legs, but no greaves. They had a manica on their right arm, wore a visored helmet, and carried a parma equestris, a round cavalry shield.

As far as weapons, the eques carried a hasta, which was a lance of about 2.5 meters in length, and a gladius.

More often than not, the equites bouts would take place at the beginning of the gladiatorial combat schedule during the games.

A re-enactor dressed as a murmillo gladiator

Probably the most famous or recognizable gladiator style was the heavy-armed murmillo.

Murmillo is actually a term for fish, and the style of his helmet resembled something of a sea creature or monster in a way. He was usually set against a thraex (Thracian) fighter, or a hoplomachus (a Greek style fighter).

When you look at this fighter, you can tell that it was a formidable opponent, and from the weapons, one could say that in the combat against others, he represented Rome and Rome’s army.

The murmillo’s torso was bare and he was protected by a manica on his right arm, and a gaiter and short greave on his right leg. The head was protected by a wide-brimmed helmet with a crest and feathers, and he bore a heavy scutum in his left hand, the large rectangular shield of Rome’s legions. Because of this protection, the murmillo fought with his left foot and shoulder forward, striking with the only weapon he carried, a gladius, in his right hand.

The murmillo never fought against his own kind, and it seems likely that the pairing of a murmillo against a thraex was the most common pairing in Roman amphitheatres.

Thraex helmet. This find is in amazing condition. Note the griffin shaped crest.

As mentioned, the thraex fighter, named after Rome’s Thracian enemies, was the main opponent of the murmillo, and was also a heavy class fighter.

The equipment of the thraex is often confused with the hoplomachus because of certain similarities such as quilted leg protection, two high greaves that reached above the knee, and a brimmed helmet with a tall crest.

The thraex carried a smaller, almost square shield known as a parmula, and his helmet was often decorated with a griffin. He had a manica on his right arm as well. Unique to the thraex was the distinctive curved short sword or sica.

In addition to being the main opponent of the murmillo, the thraex was also pitted against the hoplomachus.

Re-enactor dressed as a hoplomachus

Hoplomachus literally means ‘fights with a weapon’, which is rather obvious for a gladiator, but this heavy class fighter was representative of the ancient Greek hoplite warrior who was named after the round hoplon shield.

However, the circular shield carried by this gladiator was a smaller bronze version of the Greek shield. In addition to the body protection in common with the thraex mentioned above, the hoplomachus carried two weapons: a long dagger in his left hand, to which the shield was strapped, and a lance or spear in his right hand.

The hoplomachus usually fought a murmillo, although he could be matched against the thraex. The pairings were part of the show, an imitation of Roman soldiers (murmillo) against the foreign enemies of the past.

Artist impression of a provocator

The only middle weight gladiatorial class appears to have been the provocator.

This style of gladiator usually fought his own type, and was the only one with a protected chest in the form of a square or rectangular breastplate. He also had a half-length greave.

The provocator carried a rectangular shield, similar to a scutum and carried a gladius as his weapon. His helmet had a visor but no crest.

These fighters may not have been the headliners of the show, but their lighter weight must have made for a quick, equally-matched and impressive fight.

Mosaic depicting a battle between a retiarius and secutor.

Apart from the murmillo, the retiarius is probably the most iconic symbol of the gladiatorial family.

The name retiarius, means ‘fights with a net’.

This fighter was one of the few who had no helmet. Nor did he have a greave or shield. However, the retirarius did have a manica protecting his left arm, as well as a galerus, a tall metal shoulder guard. His weapons consisted of a net, a trident, and a pugio, or dagger.

A trident, one of the weapons of a retiarius.

Surprisingly, this fighter was a new category that was introduced during the imperial period. He was a light fighter, and though he did not pit well against the heavy, military-themed fighters, he was sometimes pitted against them during the Empire. Most often, however, the retiarius met the secutor on the sands of the arena. Sometimes, he even fought against two secutores!

The pairing of a retiarius and secutor was a storyline, a tale of the fisherman against a sea creature(s). Sometimes a set or stage was erected on the arena floor for this performance, with a bridge, or pons, from which the retiarius could fight against his one or two foes. At times, they even fought over real water!

The helmet of a secutor. Note the small eye holes and covered ears.

The secutor, the opponent of the retiarius, was also sometimes called a contraretiarius.

This gladiator was similar to the murmillo, but was designed specifically to fight the retiarius. He differed from the murmillo in the type and shape of helmet that he wore. Not only did the helmet look like a fish or sea creature, but it also had small eye holes that were deliberately intended to protect the fighter against the points of the retiarius’ trident. His hearing and vision were severely hampered by the helmet, but his heavy protection evened the odds against his more agile opponent. The secutor was not a fighter to mess with!

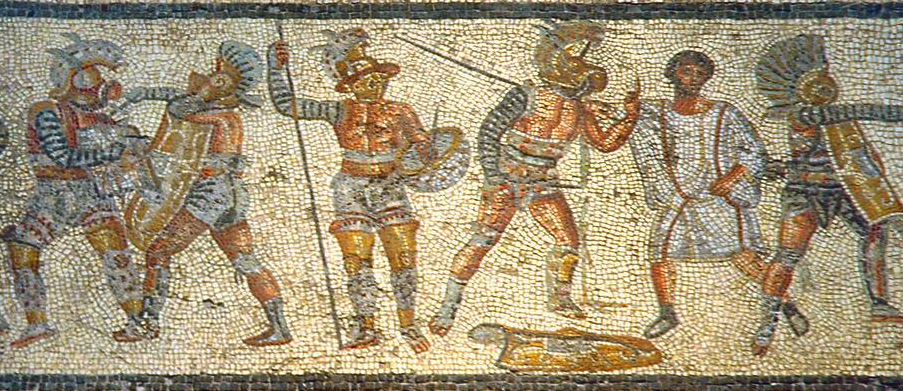

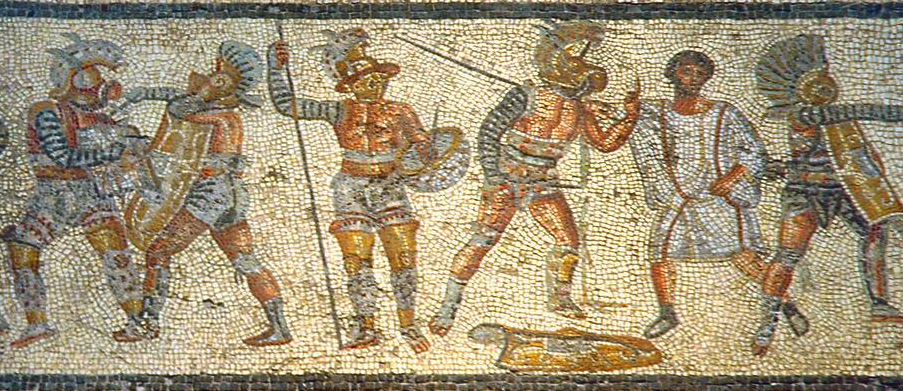

Mosaic depicting various types of gladiators, along with a referee (second from the right)

Those were the main types or classes of gladiators that appeared across the Roman Empire and in the amphitheatres of Rome.

However, there were other types of gladiators such female gladiators who depicted Amazon warriors, as well as gladiators with regional variations in the provinces.

Some other types included the essedarius, or war-chariot fighter who represented Rome’s Celtic enemies, the dimachaerus who was a fighter with two swords or daggers, and the crupellarius who was a sort of super heavy-armed gladiator.

There was also the aquerarius, a sort of retiarius with a lasso or noose, and the saggitarius who, you guessed it, was an archer gladiator. Between bouts, or at the half-time intermission of the games, you might also catch a glimpse of the paegniarius who was not for fighting, but more for comic relief like the clowns during a half-time show or intermission.

A wild beast hunt in the arena.

The world of gladiatorial combat was vast and better regulated than we are led to believe in movies. We’ve but scratched the surface here. The combats were not only on sand between men, but there were also venatio (wild animal hunts), and naumachiae (mock naval battles) to entertain the masses of Rome and the Empire.

There is much more to learn about this bloody aspect of Roman society and sport. If you want to read more, two very accessible books are Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome edited by Eckart Kohne and Cornelia Ewigleben, and the Osprey Publishing ‘Warrior’ series book Gladiators: 100 B.C. – A.D. 200 by Stephen Wisdom and Angus McBride.

But we aren’t done with gladiators!

Very soon on the Writing the Past blog, we’ll have a special guest post from archaeologist Raven Todd Da Silva about the infamous ‘turn of the thumb’ in gladiatorial games. Make sure that you are signed-up to the Eagles and Dragons Mailing List so that you don’t miss Raven’s post or any others that are coming up!

For now, I hope you’ve enjoyed this peek into the world of gladiators.

Thank you for reading.

The Colosseum, also known as the Flavian Amphitheatre