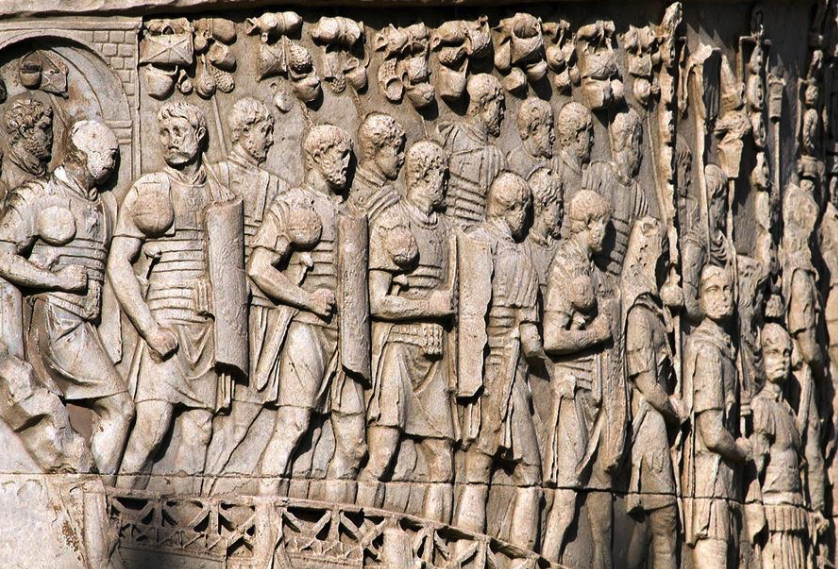

The Roman army. Those few words conjure images of blood and battle, marching legions spreading out across the ancient world. It was perhaps the most efficient military force in history, synonymous with skill, discipline, and invention.

Wherever we travel today in lands that were formerly part of the Roman Empire, we see the remains of that ancient civilization, and the remnants of Rome’s legions.

Few signs of ancient Rome’s built heritage compare with the military fortresses and forts that dot the landscape to this day. These ruins have been crucial in painting a picture of what life was like for the men of Rome’s legions, how they lived while on campaign.

There were, of course, many different types and sizes of camps and structures built by Rome’s armies across the Empire. There was the castrum (legionary fortress), the castellum (smaller camp or fort), the burgus (a small structure such as a tower, also known as a turris), signal stations and more.

In this blog, we’re going to take a brief look at that most important construction (other than roads!) of the Roman army: the legionary fortress.

In the early days of the Roman Republic, the Roman army was a field army that went out, fought actions, and then returned. But as Rome conquered more of its neighbours around the Mediterranean basin, and north and northwest into Europe, it gathered more territories that would require garrisons if they were to be held.

There were two varieties of the Roman army camp, or castrum– the temporary summer marching camp, or castra aestiva, and the more permanent winter camp, or castra hiberna.

Temporary camps were constructed at the end of every day by the men of a legion on the march, and then torn down the next day before setting out again so that the fort could not be used by the enemy. Roman legionaries, who came to be known as ‘Marius’ mules’, carried everything they needed on their backs, and that included two wooden stakes for fortifications, and a dolabra, or pick axe, which they used to shift earth for those fortifications.

Can you imagine marching twenty to twenty-five miles in one day and then having to dig ditches and create fortifications at the end of it? The men of the legions did this as a matter of routine!

The temporary camps were a sort of organized tent city where every eight-man tent (leather or canvas) for a contubernium was pitched in the same place at the end of every day. Efficiency and order were the name of the game, and the Romans were masters of both.

But the men of the legions, when at the outer reaches of Rome’s growing empire, needed warmer, more permanent quarters during the winter months outside of the campaigning season. Hence, the castra hiberna.

The requirement for permanent winter camps for every legion, in the provinces in which they were based, was issued by the emperor Augustus. The largest of these permanent camps could hold as many as two full legions! That’s over ten thousand men.

During the Julio-Claudian era, the walls of permanent camps were made of earth and wood, but from the Flavian era onward, walls were constructed of brick and stone, buttressed with earth. The structures within the permanent fortresses also evolved from their initial timber construction to more solid, long-lasting stone structures.

But how did the Romans decide where to put their camps, and how did they erect them? How were they defended? What did a legionary fortress or fort look like on the inside?

We’ll explore these questions next.

One simple formula for a camp is employed, which is adopted at all times in all places. (Polybius)

It would be a mistake to think that every legionary camp or base was exactly the same wherever you went in the Roman Empire. There was in fact a lot of variation due things like the terrain, the size of the force, and the preferences of the commander etc. But, there were certain features that were always the same, as is hinted at in the quote by Polybius above.

The first step would be to pick a suitable site for a fort that was both safe and strategic. A hill top was preferable, as was a site near to a waterway and water supply, as well as the road network if there was already one in place. Communication, hydration, and sanitation were essential!

Once a site was chosen, the ground was levelled by the troops (some stood on guard duty while most dug in). Generally, the first place to be marked out in a legionary fortress was the site of the principia, the headquarters building, at the intersection of the via Principalis and via Praetoria. This was marked with a white flag, and from here the rest of the fort’s grid was set up using a groma, a planning instrument with four plumb lines that helped to plan straight roads and to lay out the streets of the fort at perfect right angles.

Here is a short video (see minute 5:15) from historian Adam Hart Davis on how the groma was used for planning roads:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pUoSO5Rip7I

Using the groma, the intersections of the main streets of the fortress, the via Principalis and the via Praetoria, were laid out, thus allowing for the positioning of other buildings such as the tents or houses of the other officers, areas for cohorts, granaries etc.

Once the dimensions of the fort were set out, it was time to build what was perhaps the most important element of the fort: the walls.

When it came to linear defences, the Romans had everything covered. Actually, when it came to the defences of a fort, there were a few more elements besides the actual wall.

The fossa was a ditch in front of the rampart or wall of a Roman fort. There could be one or several fossae for a Roman fort, so this was variable. They could be up to twelve feet deep and three feet across, but these dimensions could also vary. Sometimes, sharpened stakes were also placed at the bottom, a little extra surprise for would-be attackers.

Behind the fossa or fossae of a fort were the vallum and agger, the raised embankments with sharpened stakes. So, after crossing the ditch of the fossa, an enemy would have to climb the embankment before tumbling down another ditch, after which he would be met with the wall of the fort.

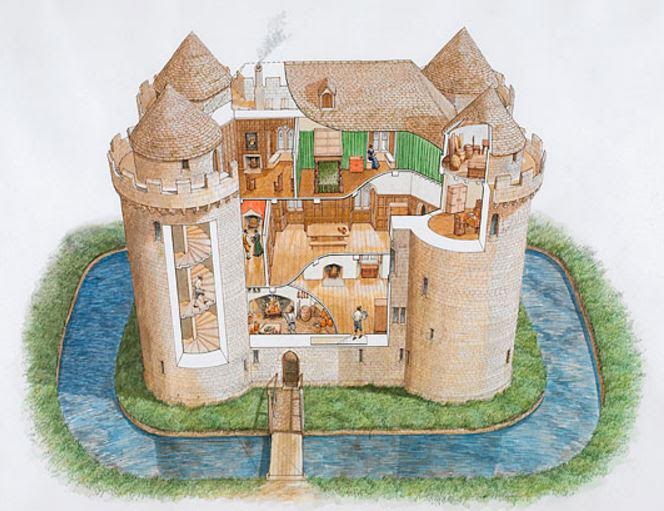

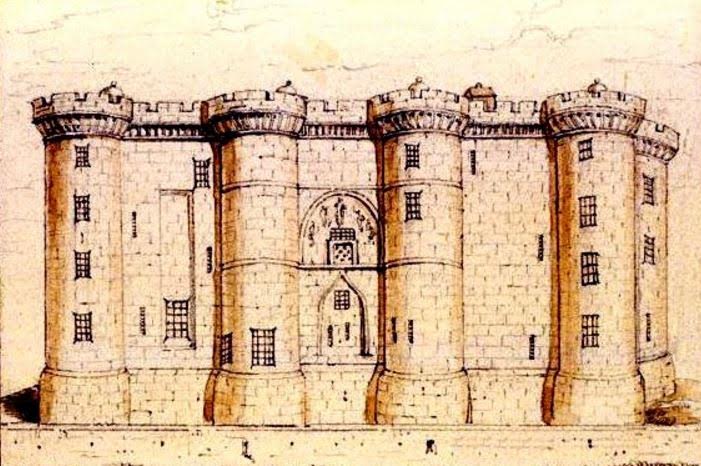

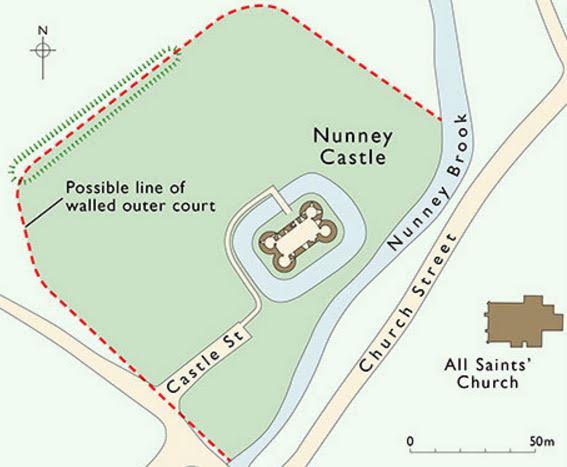

The walls of camps varied in the materials used and the height they reached, but for the most part, the walls of permanent camps were eventually built in stone and could reach a height of ten to twelve feet, or up to four meters. During the Republican era, according to Polybius’ writings, forts tended to be square, but in the early Empire the preference was for irregular quadrilateral, and then a rectangular footprint. In the later Empire, any shape became possible, even circular!

Generally speaking, the walls of Roman forts were not very high, compared with their medieval equivalents, but the defences before those walls made it difficult for an enemy to breach the walls, especially under heavy fire from the legionaries on duty. There were not always towers on the walls of a Roman fort in the Republic and early Empire, but eventually, walls came to be toped by battlements called propugnaculae, and these were of different shapes and sizes.

Reconstructed, temporary defences at Alesia, site of Caesar’s defeat of the Gaulish forces led by Vercingetorix

Towers came into use too, with square ones being more common as they were quicker and easier to build, but later, after the reign of Marcus Aurelius, round and even pentagonal towers were built because of their superior strength. Sometimes, artillery was set atop the towers.

Because every Roman fort had four gates, these were also an important part of the fortress architecture, not least because they were a possible weak point. Early on, the gates were of a titulum or clavicula type, which means that an earthen wall was erected before the opening of the gate, directly in front (titulum) or on an angle (clavicula). However, from the time of Vespasian, gates were set into the walls themselves, sometimes with towers rising above them. These gates could allow up to ten men abreast to march through.

The last of the linear defences was the intervallum. This was a broad open space between the inside of the wall and the first buildings of the fort. In addition to this being a sort of buffer zone against enemy fire, it could also be used to store supplies and graze animals. However, the intervallum was eventually done away with and the buildings of the legionary base were built right up to the side of the interior walls of the fort.

So, what did one find inside the walls of a Roman legionary base?

A city for a legion.

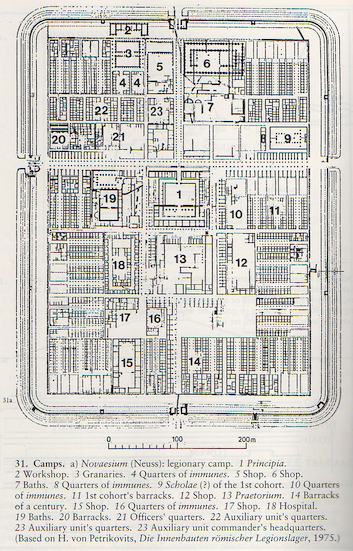

Full plan of the legionary fortress of Novaesium (Neuss), from The Imperial Roman Army by Yann Le Bohec

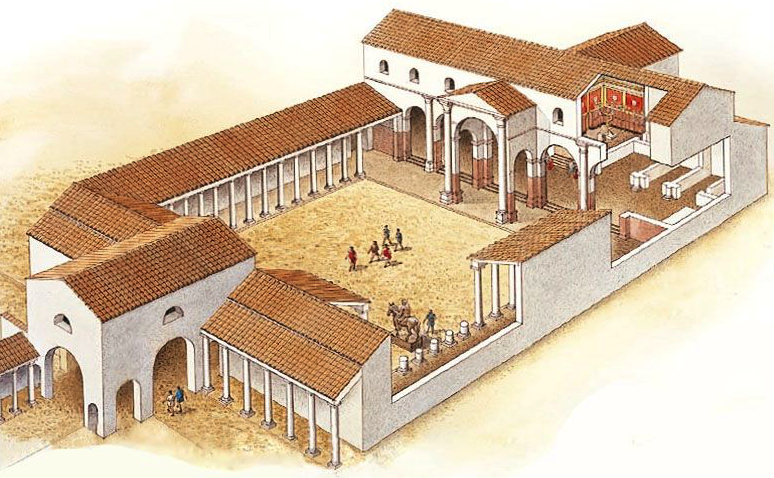

There were myriad buildings with as many purposes within the walls of a legionary fortress, and most of these would have been present, on a lesser scale, in smaller forts. At first, they would have been built in timber, and later, stone.

The most common structure was, of course, the barrack block. This was the long, rectangular building that housed the troops. For a legionary fortress, there would have been up to sixty-four barrack blocks. Each of these held a century of eighty men, and a contubernium of eight men would have shared one suite. Centurions had their own suite of rooms at the end of each block, possibly with their own lavatory. There might also have been a small mess room, and storage rooms.

A portion of the surviving barrack blocks of the fortress at Caerleon, Wales. This was the home of the II Augustan legion.

If you look at the previous blueprint of a fortress, you will see the barrack blocks in different sectors of the fortress.

The heart of the legionary base, however, was the principia, or headquarters building at the centre of the fortress.

The principia of a fortress was one of the larger buildings because it included the offices of the legate, camp prefect, and the six tribunes assigned to every legion. There was also the armoury, and the tabularium legionis and tabularium principis, the records offices of the legion and its commanders. These would have been located around a central courtyard where offerings could be made and assemblies addressed.

But there was more to the principia than that.

The treasury was also located in the principia, as well as that all-important room known as the sacellum, the place where the sacred standards and imagines of the legion were kept along with the most important emblem of Rome’s legions, the aquila, or eagle.

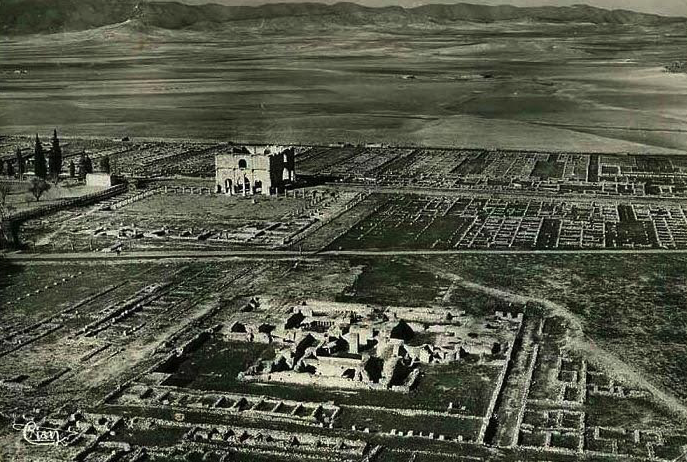

The ruins of Lambaesis legionary fortress in Numidia (modern Algeria). You can see the large principia building toward the top left. What is unique about Lambaesis is that instead of a basilica there was an open air courtyard in front of the principia.