We are past the midway point in this blog series on The World of Isle of the Blessed in which I share the research that went into the creation of the latest Eagles and Dragons release.

I hope you’ve enjoyed it so far!

Last week in Part IV, we looked at the imperial court of Severus and the main players who would have been present in Eburacum during the Caledonian campaign. If you missed it, you can check it out HERE.

In Part V, we’re going to be taking a brief look at one of the pivotal moments in Rome’s history: the death of Emperor Septimius Severus.

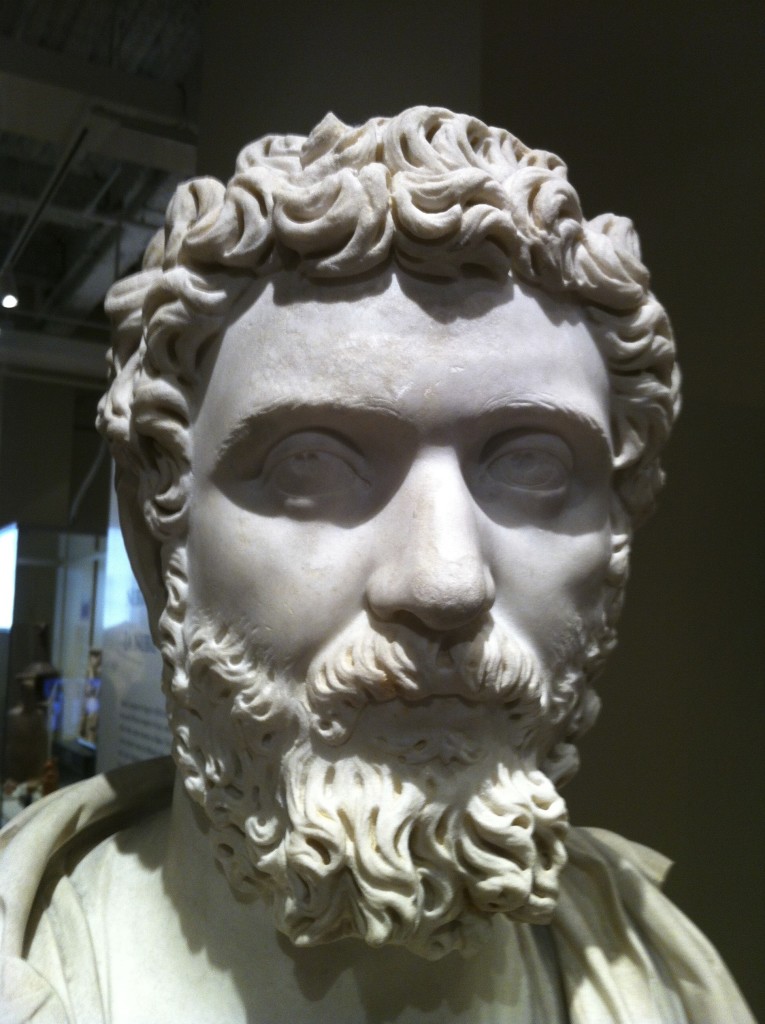

Septimius Severus

Severus, seeing that his sons were changing their mode of life and that the legions were becoming enervated by idleness, made a campaign against Britain [Caledonia], though he knew that he should not return…

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, 11-1)

In Warriors of Epona (Eagles and Dragons, Book III), Septimius Severus and his sons, Caracalla and Geta, arrive in Britannia for the invasion of Caledonia, and the sources tell us that this was partially to occupy the two sons who were running rampant in Rome after the execution of the Praetorian Prefect, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus. You can read more about the invasion of Caledonia HERE.

However, Severus had been ill for many years, mainly from gout, and perhaps arthritis. But he was a tough specimen, a man who had come out the victor in the previous civil war against Pescennius Niger and Clodius Albinus, and then as emperor had been victorious against the Parthian Empire. After the civil war, Severus brought a period of strength and stability to the Empire that saw its borders at their greatest extent and his power almost absolute, due to the strength and loyalty of the army.

Severus constantly looked to the stars…

One interesting fact about Septimius Severus and his supremely intelligent empress, Julia Domna, was that they were great believers in astrology and the messages the gods inscribed on the stars regarding their fates. Their astrologer was consulted in all things and went wherever they went.

It is for this reason, it is believed, that when the emperor set out for Caledonia, he knew that he would not see Rome or Leptis Magna, his north African home, again.

He knew this chiefly from the stars under which he had been born, for he had caused them to be painted on the ceilings of the rooms in the place where he was won’t to hold court, so that they were visible to all… He knew his fate also by what he had heard from the seers; for a thunderbolt had struck a statue of his which stood near the gates through which he was intending to march out and looked toward the road leading to his destination, and it had erased three letters from his name. For this reason, as the seers made clear, he did not return, but died in the third year. He took along with him an immense amount of money.

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, 11-1)

The Caledonian campaign began in A.D. 208. About three years later, Emperor Septimius Severus did indeed die at Eburacum (modern York) on February 4th, A.D. 211.

It seems the seers and astrologers had been correct.

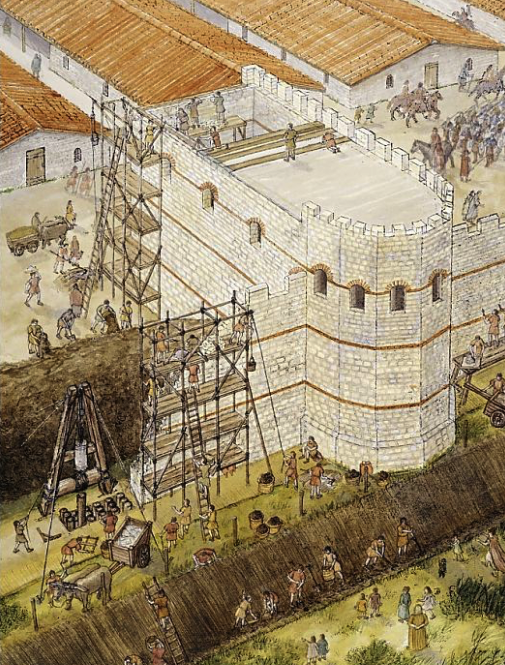

Roman York around A.D. 210. Construction of the interval tower by Tracey Croft. (Historic England)

During the Caledonian campaign, Eburacum had been the administrative capital for the imperial court. Severus’ son, Geta took care of administration, while Caracalla and his father carried on with military actions against the Caledonians and Maeatae in the North.

However, due to Severus’ ill health, he was forced to return to Eburacum to await the arrival of those stars under which he knew he was to expire.

Herodian, the other historian for the period, gives us his account:

Now a more serious illness attacked the aged emperor and forced him to remain in his quarters; he undertook, however, to send his son out to direct the campaign. Caracalla, however, paid little attention to the war, but rather attempted to gain control of the army. Trying to persuade the soldiers to look to him alone for orders, he courted sole rule in every possible way, including slanderous attacks upon his brother. Considering his father, who had been ill for a long time and slow to die, a burdensome nuisance, he tried to persuade the physicians to harm the old man in their treatments so that he could be rid of him more quickly. After a short time, however, Severus died, succumbing chiefly to grief, after having achieved greater glory in military affairs than any of the emperors who had preceded him. No emperor before Severus had won such outstanding victories either in civil wars against political rivals or in foreign wars against barbarians. Thus Severus died after ruling for eighteen years, and was succeeded by his young sons, to whom he left an invincible army and more money than any emperor had ever left his successors.

(Herodian, History of the Empire, XV 1)

Imperial Family – The Severans

The death of Septimius Severus is a crucial moment in Isle of the Blessed, and indeed in the entire Eagles and Dragons series.

I have been writing about this fascinating emperor for a long time, since Parthia, and then, as the stars loomed above him, as his day of death appeared on the horizon, it was time to explore his thinking toward the end.

How difficult it must have been for such a strong individual to face his end? After winning, creating, and ruling a vast, thriving empire, how could he deal with saying goodbye to it all?

It was a privilege to write about it in Isle of the Blessed.

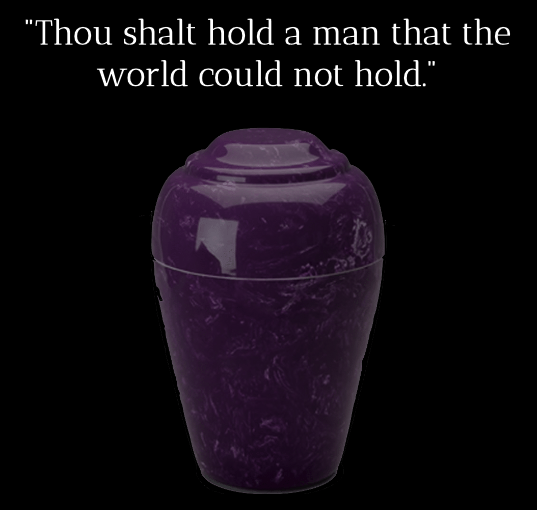

The research into Severus’ death was also fascinating. Cassius Dio gives some details:

…his body, arrayed in military garb, was placed upon a pyre, and as a mark of honour the soldiers and his sons ran about it; and as for the soldiers’ gifts, those who had things at hand to offer as gifts threw them upon it, and his sons applied the fire. Afterwards his bones were put in an urn of purple stone, carried to Rome, and deposited in the tomb of the Antonines. It is said that Severus sent for the urn shortly before his death, and after feeling of it, remarked: “Thou shalt hold a man that the world could not hold.”

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, 15, 2)

One can imagine Severus, staring at the stars he had had painted everywhere, and at the stone urn that would hold his remains, but my research into the death of this great emperor of Rome led me to something even more fascinating.

The funeral pyre of Septimius Severus was said to have been the largest pyre ever to be seen in Britannia.

But what did such a thing look like? Where in Eburacum could it have been located?

Numismatology, the study of coinage, has been extremely useful to me in my research into the Severans over the course of this series of novels, and once again, it proved extremely useful.

When looking for any information I could find on the death of Severus, I came across an image of a coin minted by Caracalla after the death of his father. It was perfect, for this coin depicted exactly what I was looking for…

Silver denarius showing the funeral pyre of Septimius Severus

On this coin is depicted the funeral pyre of Septimius Severus himself. It provided me with the information I needed to accurately describe this event.

Serendipity does indeed happen in research too!

The other question was the location of the pyre. Where could it have been located? Of course, the pyre would have had to be outside the city walls of Eburacum. But the ustrinum, the burning place, for such a large pyre would have to be far removed from the city.

Here too, the stars aligned for my research.

In modern York (ancient Eburacum) there is a place called ‘Severus Hill’ which is a large hill (now topped by a water tower) in an otherwise flat landscape that some historians believe was created by glacial shiftings millions of years ago.

However, I discovered that there is another theory about Severus Hill that the feature was not created by glaciers, but rather that it is the overgrown remains of Septimius Severus’ giant funeral pyre.

Severus Hill, and its water tower. (photo: yorkpress.co.uk)

I thought about this, about the distance from the ancient city walls (about 2 miles) and the toponymics of the place (place name). Whether the theory is absolutely true or not, it fit well with the story I was trying to tell.

It is wonderful when a plan, erm…plot, comes together!

Thus, my time with Septimius Severus, one of Rome’s great emperors, has come to an end. I will miss him.

He was not perfect, to be sure, but his life and actions have been fascinating to explore. He had great successes, but he also had failures, and perhaps his greatest failure was to entrust the empire he had built to his two sons, Caracalla and Geta.

Severus had, at one point, criticized Marcus Aurelius for making Commodus his heir, but he in turn had made the same mistake.

And the Empire would pay for it.

Still, Septimius Severus was an emperor until the very end, when his stars flickered and faded. His final words, as Cassius Dio tells us, were: “Come, give it here, if we have anything to do.”

I hope you have enjoyed this part in The World of Isle of the Blessed. There is more to come!

Tune in next week for Part VI when we will be looking at a particular archaeological discovery that sheds a gruesome light on the immediate aftermath of Severus’ death.

Thank you for reading.