When we think of ancient Rome and the Roman Empire, there are several images that come to mind – massive armies, marble temples and palaces, risqué parties, and emperors behaving badly. Whether these are accurate or not is somewhat beside the point. Depending of the books they’ve read, or the movies they’ve watched, different people will think of different things when it comes to the Roman world.

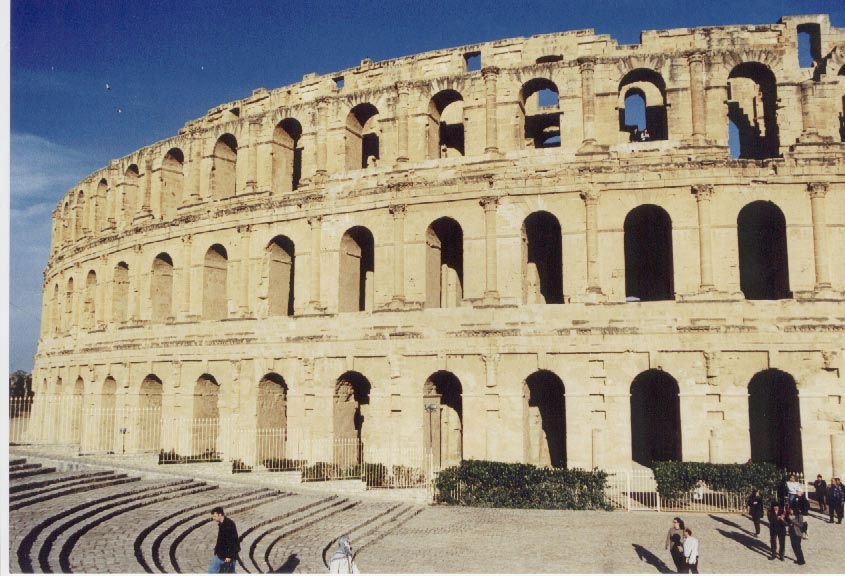

One thing that many people will think of when you utter the words ‘Ancient Rome’ is the amphitheatre (usually the Colosseum) and gladiators.

Gladiators – and charioteers, of course, – were the star athletes of their day, even though they were slaves on the social scale.

What had begun long ago as a funeral rite, over time, became one of the greatest and bloodiest entertainments in the Roman world.

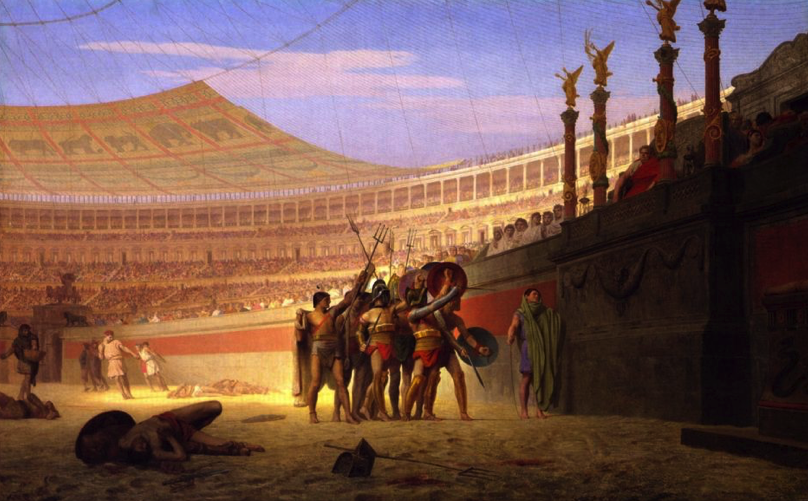

In ancient Rome, gladiatorial combat was a popular form of entertainment. It was an integral part of Roman culture and provided a spectacle for the masses. Gladiators were trained fighters who engaged in mortal combat with each other, wild animals, or prisoners of war. The gladiatorial games were held in amphitheatres, and thousands of people would gather to watch the fights.

Ave Caesar, Morituri Te Salutant (1859) by Jean-Léon Gérôme

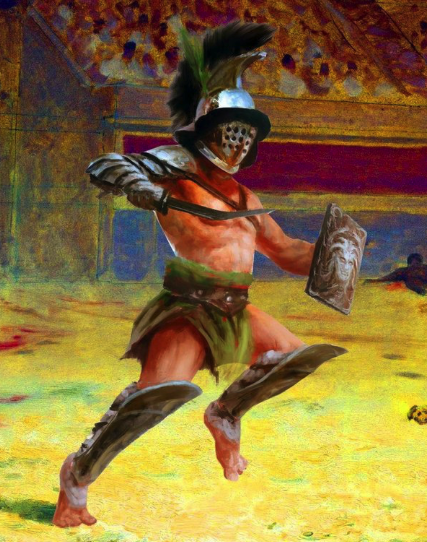

Despite the popularity of the subject today, and movies involving gladiators such as Gladiator or Pompeii, most newcomers to Roman history may not know that there were many different types of gladiators with distinctive weapons and styles of fighting. The Roman world was, after all, quite diverse, and the same went for the sands of the arena.

In this short blog post, we will explore the different types of gladiators and the weapons that they used.

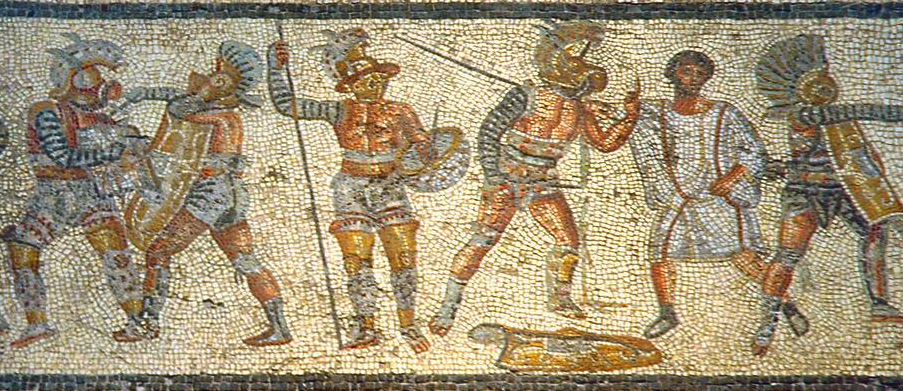

Retiarius

Roman mosaic showing a Retiarius in combat

The Retiarius was a lightly armoured gladiator who fought with a trident and a net. He also wore an arm and shoulder guard on one side, and sometimes greaves. The net was used to ensnare his opponent, and the trident was used to stab him. The Retiarius was often pitted against the Secutor, who was heavily armoured and carried a sword and a shield.

Secutor

Artist Impression of a Secutor gladiator

The Secutor was a heavily armoured gladiator who fought with a sword and a large shield. He wore a helmet with a rounded top and small eye holes that gave him the look of a sea monster to be fought by the Retiarius, the fisherman, for whom he was the perfect match. The Secutor’s sword was short and straight, allowing him to make quick strikes and parry attacks. The Emperor Commodus, who used to fancy himself a gladiator, often fought as a Secutor.

Murmillo

A re-enactor dressed as a murmillo gladiator

The Murmillo was a heavily armoured gladiator who fought with a gladius and scutum. He wore a large helmet, an arm guard or manica, greaves with thick padding beneath, and a thick leather belt, or balteus. The Murmillo was often pitted against the Thraex, who wore a helmet with a griffin on it and carried a curved sword.

Thraex

Artist impression of a Thraex gladiator

The Thraex, or ‘Thracian’ fighter, was a lightly armoured gladiator who fought with a curved sword, called a sica, and a small, square shield. He wore a helmet and thick greaves. The Thraex was designed to be the perfect match for the Murmillo, and so these two gladiators were often paired off for the entertainment of the crowd.

Hoplomachus

Re-enactor dressed as a hoplomachus

The Hoplomachus was a heavily armoured gladiator who fought with a spear, a dagger, and a small round shield, reminiscent of the round shield of the ancient Greek Hoplite warriors of the past. He wore a helmet with a crest on top and a visor, a manica on one arm, and thick greaves. The Hoplomachus was often pitted against the Murmillo.

Dimachaerus

Dimachaerus – as portrayed by the character of Gannicus in the series Spartacus: Blood and Sand

The Dimachaerus was a lightly armoured gladiator who fought with two swords. He wore a helmet, arm guards, and a thick belt. The Dimachaerus was often pitted against other dimachaeri gladiators, or the hoplomachus. Because this gladiator had no shield and only fought with two gladii or curved blades, it would have required a lot of skill to survive.

Provocator

Artist impression of a Provocator

The Provocator was a heavily armoured gladiator who fought with a gladius and a scutum. He wore a large helmet with a crest on top and a visor, a greave on his forward leg, and sometimes a breastplate. This gladiator was meant emulate the Roman legionary in the arena. The Provocator was often pitted against other heavily armoured gladiators, such as the Murmillo or the Secutor.

Equites

Artist impression of two Equites gladiators

The Equites were gladiators who fought on horseback and would no doubt have added a lot of drama to the scene in the arena. They carried a lance, cavalry sword, and a round or oval shield. The Equites gladiators would also have worn a helmet, and sometimes a breastplate. The Equites were often pitted against each other or against other gladiators. The horsemanship skills would have had to be excellent to enable them to charge, wheel, and fight from horseback!

Bestiarii

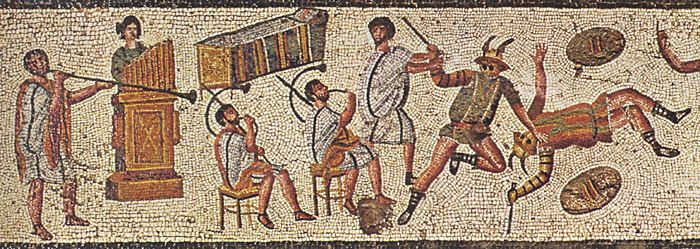

Mosaic depicting a Bestiarius fighting a leopard or tiger in the arena.

While not strictly gladiators, the Bestiarii played a unique role in the arena. They were fighters who specialized in combat against wild animals. The Bestiarii used a variety of weapons, such as spears, swords, or even lassos, to subdue and kill their ferocious opponents. These gladiators had to possess exceptional agility and bravery to face the dangerous creatures. The Bestiarii fought wild animals in the arena, while Venatores were hunters of animals on occasions of wild beast hunts in the arena for the entertainment of the populace. If a person was considered damnatio ad bestias, that person was not a gladiator, but rather someone who was condemned to death at the mercy of the beasts, such as prisoners or persecuted peoples thrown to the lions. The use of animals in the arenas of the Empire caused the extinction of many of Europe and North Africa’s animal species.

Andabatae

Re-enactor dressed as an Andabatae gladiator

The Andabatae were gladiators who fought blindfolded. They wore helmets with no eye holes, making it impossible for them to see their opponents or their surroundings. Armed with various weapons like swords, axes, or clubs, the Andabatae relied solely on their instincts and hearing to engage in combat. This added an extra layer of danger and excitement to the fights, both for the gladiators themselves and for the spectators.

Laquerarii

Artist impression of a Laquerarius

The Laquerarii were gladiators who specialized in fighting with whips. They were usually pitted against other Laquerarii or against animals, such as lions or bears. These gladiators demonstrated exceptional skill in handling the whip, using it to control and subdue their opponents or animals. Their agility and precision were crucial in navigating the dangerous encounters.

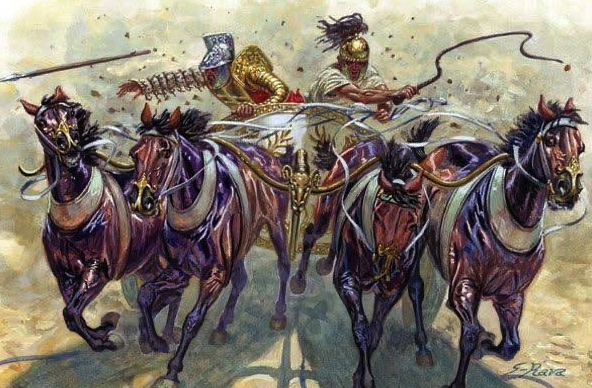

Essedarius

Artist impression of two Essedarii

The Essedarius was a type of gladiator who fought from a war chariot that was meant to emulate the vehicles of the Celtic tribes of Europe whom Rome fought in Gaul, Britannia, and elsewhere. It is unclear from the sources whether the Essedarius rode the chariot into the arena and then dismounted to fight, or if they fought from the chariot cab while a driver whisked them around their opponents. The latter explanation seems more likely as it would have been much more dramatic for the audience. Who could forget the scene in Gladiator when the chariots burst into the arena!

These are but the main types of gladiators that one would have found on the sands of the arenas about the Roman Empire. Often, gladiators might have customized their equipment or changed things up a bit to align with their fighting personas.

There were other gladiators such as archers (Sagittarius), boxers (Cestus), and others, all of them risking death in the arena for the entertainment of the crowd.

Amazon warriors as depicted in the film Wonder Woman

In addition to male gladiators, ancient Rome also saw the presence of female gladiators, known as Gladiatrices or Ludia. While not as common as their male counterparts, these female warriors brought a unique and captivating element to the gladiatorial games.

While very little is known about female gladiators and their training, we do know that they existed and that they had stage names and personae similar to their much more common male counterparts.

Amazon

Mosaic depicting Amazon type gladiatrices

As a legendary race of female warriors, it is hardly surprising that the Amazons were a popular persona for female gladiators who drew inspiration from the mythical tribe of warrior women. They fought in a manner similar to male gladiators, wielding weapons such as swords, shields, and spears. These formidable fighters showcased their skills, strength, and agility in combat, challenging the notion that gladiatorial combat was solely a male domain.

Dimachaera

Dimachaeria as depicted in the series Spartacus: War of the Damned

The Dimachaera were female gladiators who fought with two swords, similar to their male counterparts. These skilled fighters displayed dexterity and precision as they engaged in dual-bladed combat. Their agility and quick reflexes made them formidable opponents in the arena.

Secutoria

The helmet of a secutor. note the small eye holes and covered ears.

Inspired by the male Secutor gladiators, the Secutoria were female gladiators who were heavily armoured and fought with swords and shields. They wore helmets similar to the Secutors, with rounded tops and narrow eye slits. The Secutoria often faced off against other female gladiators or, very rarely, male opponents, showcasing their courage and combat prowess.

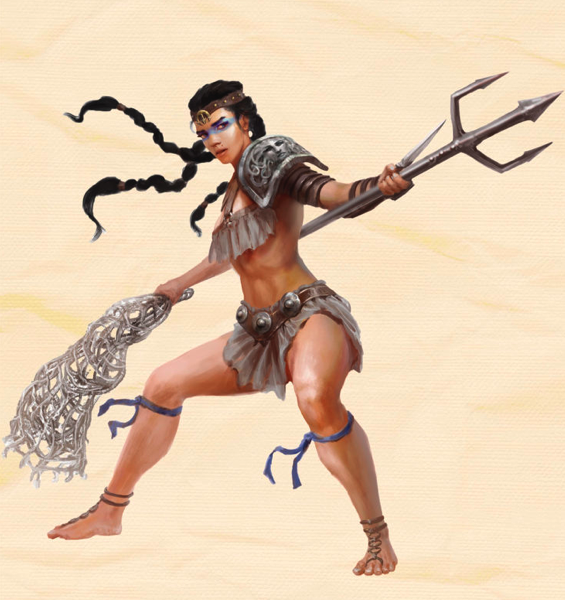

Retiaria

Artist impression of a Retiaria

The Retiaria were female gladiators who adopted the fighting style of the male Retiarius. These gladiatrices engaged in combat using a trident and a net. Similar to their male counterparts, they wore light armour and were known for their agility and finesse in capturing and subduing opponents with their nets.

Essedaria

Essedaria from the film Gladiator

The Essedaria were a unique group of female gladiators who fought from chariots, demonstrating their skill in handling horses and engaging in fast-paced combat. They carried weapons like swords, spears, or bows, and unleashed their attacks while maneuvering the chariots. The Essedaria added a thrilling and visually striking element to the gladiatorial games.

Marble relief depicting two female gladiatrices named ‘Amazon’ and ‘Achillia’

Similar to their male counterparts, there would have been variations for female gladiators who adopted different fighting styles and weaponry. Some gladiatrices fought with weapons such as swords, shields, or spears, while others engaged in more unconventional combat using whips, lassos, or daggers. The range of fighting styles and weapons used by female gladiators added diversity and excitement to the arena that the crowd would have found spectacular and even titillating.

It’s important to note that while female gladiators did exist, they were not as numerous as their male counterparts, and their participation in the gladiatorial games varied throughout different periods of Roman history. The presence of female gladiators challenged traditional gender roles and norms, providing a platform for women to showcase their skills, strength, and bravery in combat.

Just because they existed doesn’t mean, however, that female gladiators were not a controversial topic. In A.D. 11, the Senate passed a law forbidding freeborn women under the age of twenty from participating in gladiatorial combat. And almost two hundred years later, Emperor Septimius Severus outlawed participation of women in the arenas of the Empire, claiming that such spectacles encouraged a lack of respect for women in general.

Despite Severus’ decree, it seems that women continued to fight as gladiators into the third century, after Severus’ death, at places such as Ostia.

Female gladiators made their mark in ancient Rome, defying societal expectations and participating in the intense world of gladiatorial combat. Their presence added an extra layer of intrigue and excitement to the gladiatorial games, highlighting the diversity and courage of these formidable women.

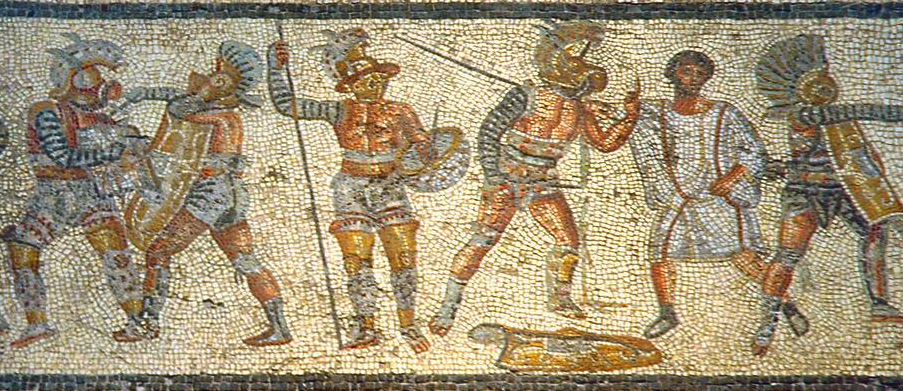

Mosaic depicting various types of gladiators

It’s important to note that while all the types of gladiators and gladiatrices and their weapons mentioned above were prominent in the Roman world, the gladiatorial games evolved over time, and variations existed within each category. Gladiator schools, known as ludi, played a significant role in training and honing the skills of these fighters. It was also big business!

The world of gladiators in ancient Rome was rich, diverse, and bloody.

It may not be Rome’s greatest contribution to society, but it has certainly left an impression that resonates today, as if the crowds of the Colosseum are still baying for blood.

Thank you for reading…