Greetings history-lovers!

Welcome back to the blog. I hope that you are all keeping well and safe during the continuing pandemic, wherever you are.

Today is Remembrance Day in Canada, the UK, and Australia, and Veteran’s Day in the United States, so I thought that it would be fitting to post something something on a military theme in honour of our men and women in service.

This week on the blog, we’re going to be taking a brief look at the foundation and organization of the Republican Roman legion.

Many readers will already be familiar with the organization of the Imperial Roman Legion, but perhaps not the formation of Rome’s early army? How did a little village on the Tiber develop into such a dominant military force in the Mediterranean world? What did the early Roman army look like, and how was it organized?

Servius Tullius, sixth king of Rome (580-530 B.C.)

In the early days, of course, Rome was ruled by kings. From 753 – 509 B.C., beginning with Romulus and ending with Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, Rome’s army was the king’s army. The king had direct command of the military.

However, as Rome conquered more neighbours in the Italian peninsula, its army grew bigger, and so a hierarchy of command was needed.

This early Roman army under the king, was made up of approximately three thousand men from the three tribes of Rome: the Ramnenses (named after Romulus himself), the Titiensies (named after Titus Tatius), and the Lucerenses (name origin unknown). The men from these tribes formed one, big army, a citizen army.

At this time, the army was commanded by a tribunus, or ‘tribal officer’, beneath the king. Other than this, however, little else is known about the chain of command in the army before the fourth century B.C.

What we do know is that Servius Tullius (580-530 B.C.), the sixth king of Rome, divided the people into classes with his constitution, and these divisions had both political and military purposes. There were financial groupings or ‘centuries’ that meant men of military age were divided according to their ability to provide their own arms and equipment for military service.

Equites were the richest, and the rest of the population, which formed the infantry, were divided into five classes with descending degrees of weapons and armour.

Below these five classes were the capite censi, or landless men.

Basically, the Servian reforms created a sort of hoplite army, based on the phalanx used in the classical Greek and Hellenistic world.

Depiction of a Greek hoplite battle

In 509 B.C. when Lucius Junius Brutus and other noblemen expelled the last king, Tarquinius Superbus, and the Roman Republic was born, the king was replaced by two consuls, also known as praetors. These men were elected every year and they held supreme civil and military power.

By 311 B.C. the army was divided into four legions, and the command of these legions was divided between the two consuls.

Each legion had six military tribunes that were elected by the comitia centuriata.

The first detailed account of the military hierarchy of the Republican Roman army comes down to us from Polybius (200-118 B.C.) who was a Greek historian during the Hellenistic period, and an eyewitness of the sack of Carthage in the third Punic War as well as the Roman annexation of mainland Greece, both in 146 B.C.

This army of the middle Republic (c. 290-88 B.C.) has come to be known as the ‘Polybian’ army, and this army was divided not into cohorts and centuries, but rather maniples.

Stele depicting Polybius (200-118 B.C.)

The total force of the Roman army at this time was four legions with a total of sixteen to twenty thousand infantry and fifteen-hundred to twenty-five hundred cavalry. Allied forces could also be called upon, and mercenaries hired, if Rome needed to bolster its forces.

At this time, praetors, who were lesser magistrates beneath the commanding consuls, could also command a legion, and in times of crisis, a dictator was appointed for a six month period, taking over full command of the army from both consuls. The dictator could himself, appoint a second-in-command known as the magister equitum, or ‘master of horse’. During the dictatorships of Julius Caesar, both Marcus Antonius and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus served as magister equitum, appointed by Caesar himself.

Apart from overall command by the dictator, from about 190 B.C., the army was still under the control of the consuls or praetors, but forces could also be commanded by legati, or ‘legates’ who were senior senators. One or more legati went with a governor or magistrate when he took control of a new province, and so they had both civil and military duties.

But what were the other officer ranks in the manipular army?

Rome’s four legions included twenty-four tribunes at this time. These were equestrian class men. Senior tribunes could also command extra legions that needed to be raised beyond the standard four.

Each tribune in the legions could select ten centurions who chose their own seconds. The most senior centurion was known as the centurio primi pili, or ‘first spear’. Centurions themselves were able to appoint an optio as a rear-guard officer, and two standard bearers, or signiferi.

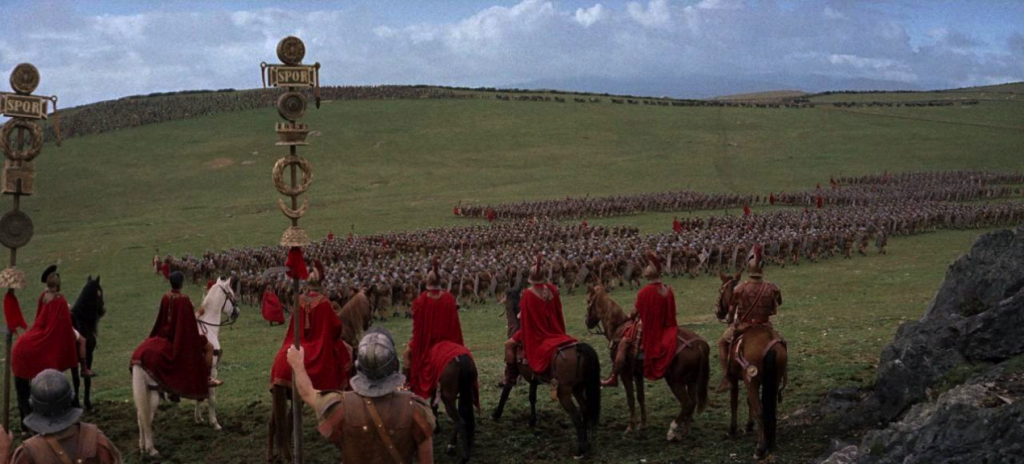

Republican Roman army formation from 1960 film, Spartcus.

Each legion was divided into maniples which were composed of two centuries each. The primus pilus centurion normally commanded the right hand maniple.

When it comes to cavalry, the legion’s force of horsemen was divided into ten turmae of thirty cavalrymen. Each turmae had three decurions who led ten men.

With all of these titles and ranks, one might think that the Republican army was actually quite similar to the imperial Roman army we are so familiar with. However, when you look at it more closely, the manipular army was quite different. Here, Polybius explains:

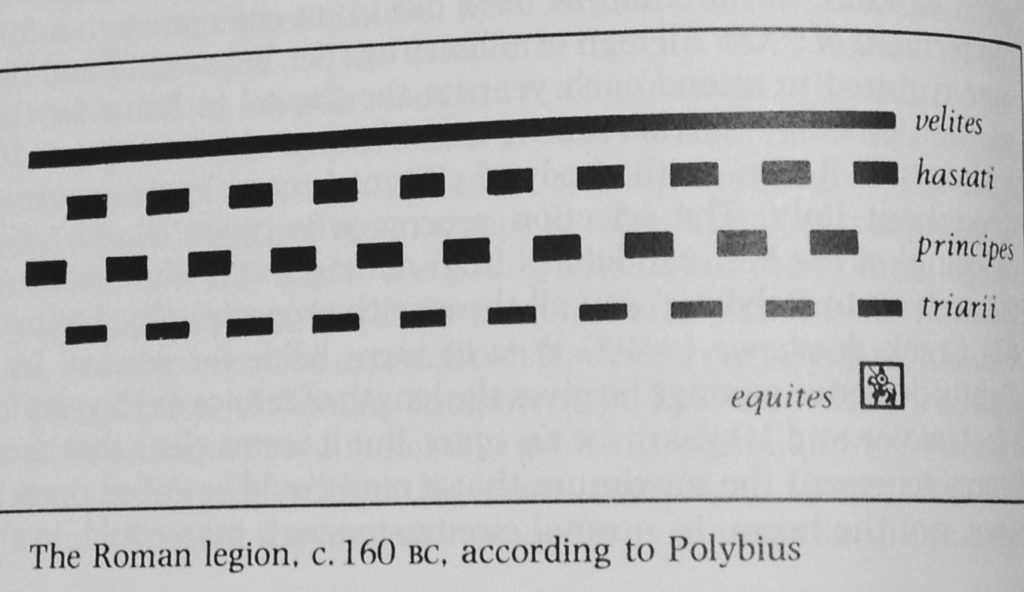

The tribunes in Rome, after administering the oath, fix for each legion a day and place at which the men are to present themselves without arms and then dismiss them. When they come to the meeting place, they choose the youngest and poorest to form the velites; the next to them are made hastati; those in the prime of life principes; and the oldest of all triarii, these being the names among the Romans of the four classes in each legion distinct in age and equipment. They divide them so that the senior men known as triarii number six hundred, the principes twelve hundred, the hastati twelve hundred, the rest, consisting of the youngest, being velites. If the legion consists of more than four thousand men, they divide accordingly, except as regards the triarii, the number of whom is always the same…

…From each of the classes except the youngest they elect ten centurions according to merit, and then they elect a second ten. All these are called centurions, and the first man elected has a seat in the military council. The centurions then appoint an equal number of rearguard officers (optiones). Next, in conjunction with the centurions, they divide each class into ten companies, except the velites, and assign to each company two centurions and two optiones from among the elected officers. The velites are divided equally among all the companies; these companies are called ordines or manipuli or vexilla, and their officers are called centurions or ordinum ductores. Finally these officers appoint from the ranks two of the finest and bravest men to be standard-bearers (vexillarii) in each maniple.

(Polybius, The Rise of the Roman Empire, Book VI.6)

The Roman legion c.160 B.C. according to Polybius (image: The Making of the Roman Army, p.34, Lawrence Keppie)

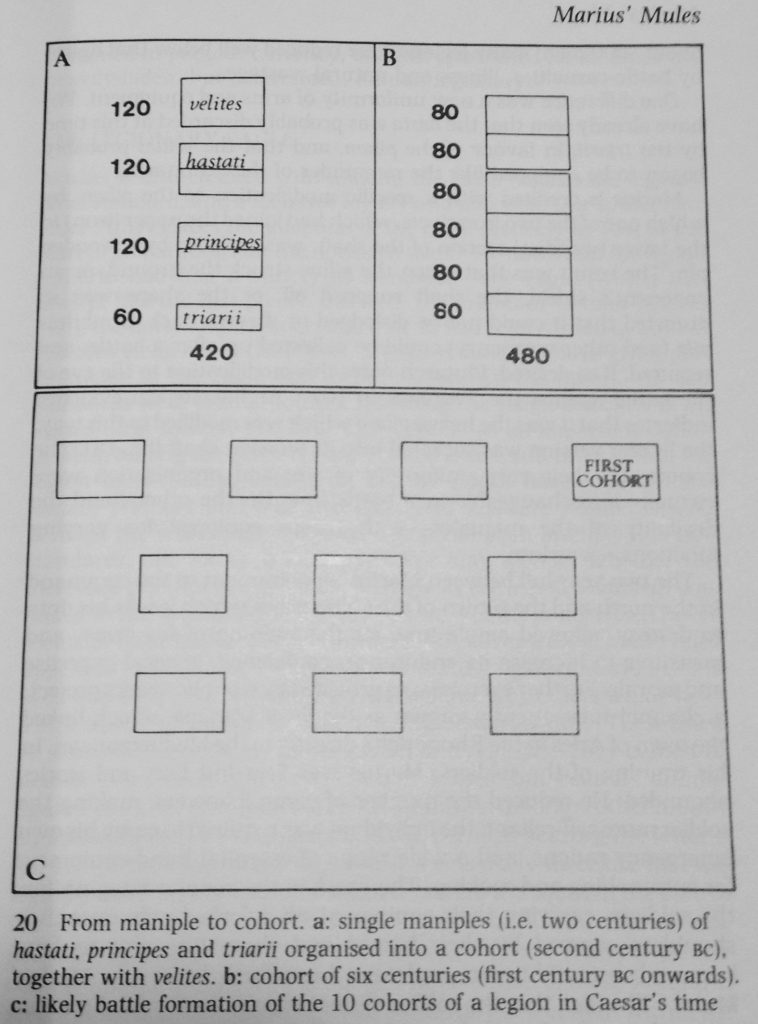

So, the Republican army contained battle formations of maniples of velites (light-armed troops in the first line), hastati (spearmen in the second line), principes (chief men in the third line), and triarii (older men in the fourth line). Around 130 B.C., men were placed in the battle lines not according to their financial status, but according to their age and experience.

Each legion had ten maniples of one-hundred and twenty men each of hastati and principes, and ten maniples of sixty men each of triarii. In addition to these, a legion had reserves of rorarii and accensi in the rear who were, it seems, servants of some sort.

When it comes to Italian allied forces, these were known as the socii, and they served in cohorts of five hundred men commanded by a praefectus. Ten cohorts of socii formed an ala sociorum which was about the same size as a legion with similar organization. This was the precursor of Roman alae, or auxiliary forces (such as Sarmatian or Numidian cavalry), during the imperial period.

Mercenary forces, such as Cretan archers, were also employed.

When it comes to the army of the late Republic (c. 88-30 B.C.), there was an increase in the delegation of military power to the legati who were, as a requirement, senators who had served as quaestors as a minimum. (For more information of the various levels of office, check out this post on the Cursus Honorum)

In 52 B.C. a law was created that required five years between holding an office and a provincial military command, and because Rome was a republic at the time, there were several commanders-in-chief of the army, the idea being that no one man could become too powerful. As we know, however, this was not a foolproof system!

The legions were still commanded by six tribunes but these men were increasingly young and ambitious and hoping to enter into the Senate. Tribunes and prefects could go on to be legates too.

As new territories were acquired, and as Rome expanded, new legions were raised to hold those new territories. Magistrates were given more powers and longer terms beyond the previous one-year, and proprietors and proconsuls were given command of legions for longer periods. An example of this is Caesar’s command in Gaul.

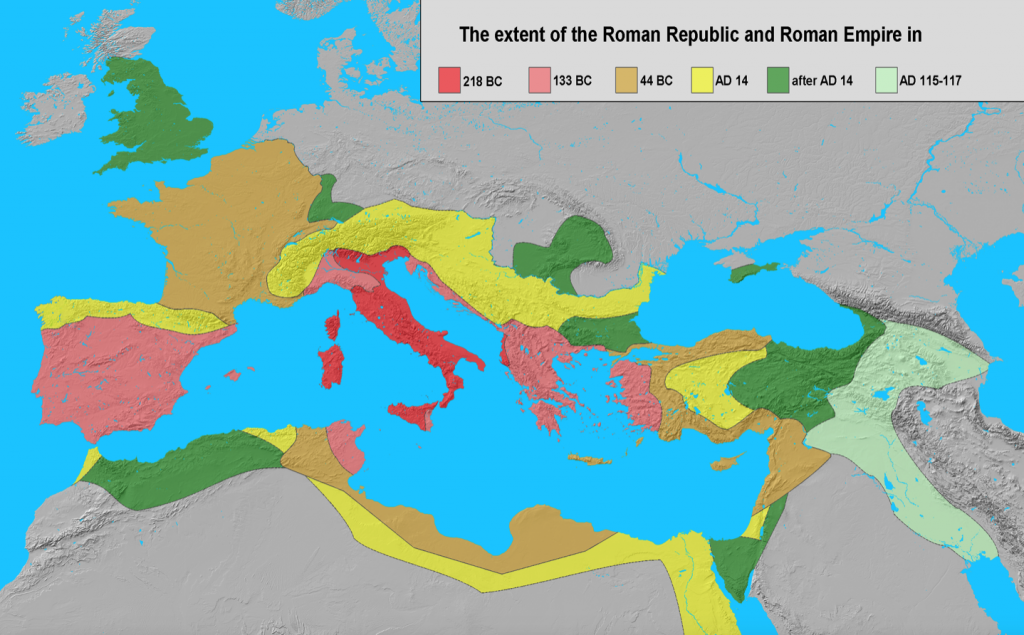

Growth from Republic to Empire (Wikimedia Commons)

The greatest, most long-lasting changes to the Roman army occurred around 107 B.C. under what has come to be called the Marian Reforms.

Gaius Marius was a pro-Plebeian statesmen and successful general who served seven terms as consul of Rome. He led successful campaigns in North Africa and Germania. But Marius is perhaps best known for the major changes to the Roman army in which he moved things from a citizen, manipular militia to a standing, professional army.

Under Marius’ leadership, the Roman army became better, more evenly equipped, and went from the widespread use of maniples to cohorts as the main sub-unit of the Roman legion. This was the birth of the imperial Roman legion we are familiar with today.

The maniple vs. the cohort (image: The Making of the Roman Army, p. 65, Lawrence Keppie)

But perhaps one of the biggest reforms Gaius Marius made, and one which won him a lot of enemies in the upper classes, was to open up the ranks of Rome’s legions to the capite censi, that class of landless men who, once in the army, were seen by some to be the cause of greed and lawlessness in the ranks.

Nevertheless, this new Roman army made a marked improvement. Soldiers had better weapons and carried all their equipment on their own backs which made troop movements and marches more efficient. This is where the term, ‘Marius’ Mules’ comes from.

Gaius Marius is also credited with the introduction of the eagle standard, the aquila, given to each legion and which became a focus of loyalty and affection for the troops.

Image of a Roman eagle standard, or ‘aquila’ (Wikimedia Commons)

The Roman army of the early Republic was now drastically changed, larger, and more efficient. More legions were created as Rome expanded its reach around the Mediterranean basin and into Europe. As the lower classes of Rome’s citizens were allowed to enlist, they found purpose, coin, and opportunities in a new, professional, standing army.

Of course, the army would continue to evolve with career soldiers serving for twenty years or more, and other classes moving up the ranks during such periods as the reign of Septimius Severus who also allowed soldiers to marry. The soldiery would later make emperors, or destroy them.

One thing was certain: wherever in the world Rome could be found, the Roman army had got there first.

Thank you for reading.

As always, we would like to thank all our men and women in service, and their families, for the sacrifices they have made, and continue to make, to keep us all safe and free.

On November 11th, and every other day of the year, we remember you and are grateful.

This year, Eagles and Dragons Publishing is proud to have supported Wounded Warriors Canada and their important PTSD Service Dog Program, and the Couples-Based Equine Therapy Program both of which play an important role in the healing process for service men and woman and their families.

Check out the Wounded Warriors Canada website here:

https://woundedwarriors.ca