When you enter the abode of the god

Which smells of incense, you must be pure

And thought is pure when you think with piety

This was the inscription that greeted pilgrims who passed through the propylaia, the main gate into the sanctuary of the god Asklepios at ancient Epidaurus.

Last week we looked at the world-famous ancient theatre of Epidaurus, and the marvel of artistic engineering that it was. This week, however, we will step into the quiet realm of the sanctuary of the God of Healing, a place that was famous around the ancient world for the miracles of health and healing that occurred there.

After our visit to the theatre, when the sun was at its most intense, we walked back down the steep stairs toward the back of the sanctuary where the small, but wonderful, site museum is located. It was time to get into the shade for a few minutes.

This museum is quite unassuming, but it has some amazing architectural and everyday artifacts.

The vestibule contains cabinets filled with oil lamps, containers and phials that were used for medicines and ointments within the sanctuary, as well as surgical implements and votive offerings.

Above the cabinets and into the main room of the museum, there are reliefs and cornices from the temple of Asklepios decorated with lion heads, acanthus, and meander designs, many of which still have the original paint on them.

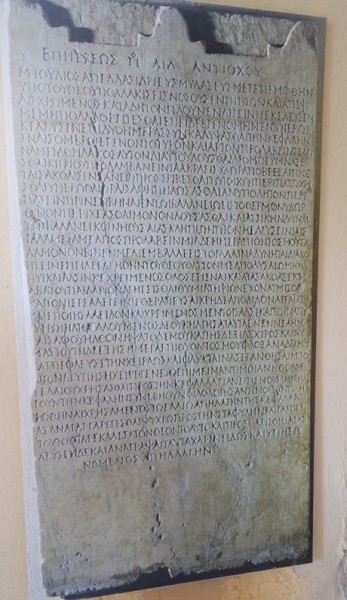

However, in the first part of the museum are some plain-looking stele that are covered in inscriptions recording the remedies given at Epidaurus, and the miracles of healing at the sanctuary in ancient times. These inscriptions are where much of our knowledge of the sanctuary comes from.

We walked out of the vestibule into the slightly crowded main museum room where most of the tourists who were on site seemed to be cooling off.

But I didn’t notice the people. My eyes were drawn, once more, to the magnificent remains of the Tholos, and temple of Asklepios – ornate Corinthian capitals, cornices decorated with lion heads, and the elaborately-carved roof sections of the temple’s cella, the inner sanctum.

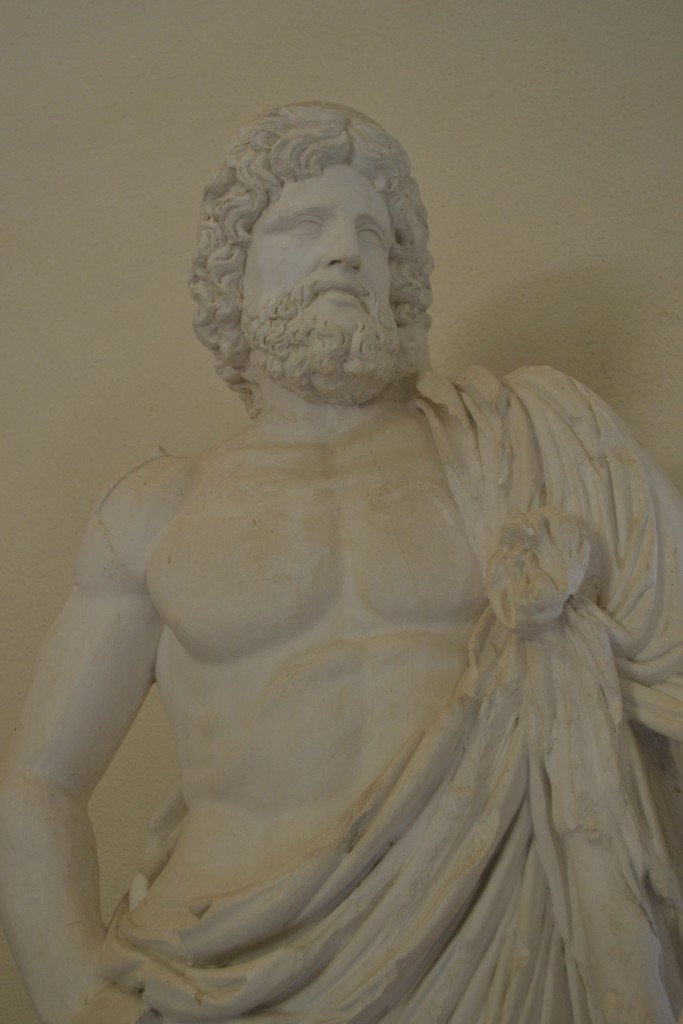

I stood before the statues of Athena and Asklepios that had adorned various parts of the sanctuary, and the winged Nikes that stood high above pilgrims, gazing out from their corners of the roof of the temple of Artemis, the second largest temple of the sanctuary.

I wondered if the people walking through the museum realized how beautiful the statues they were walking by actually were, the meaning they held for those coming to the sanctuary in search of help.

Once we had cooled off a bit, we gathered ourselves to head back out into the heat and head for the sanctuary of Asklepios just north of the museum and theatre.

The site was completely empty.

It seemed that most visitors headed for the theatre alone, some to the museum afterward, but none wanted to tough it out among the ruins of one of the most famous sanctuaries in the ancient world.

The Sanctuary of Asklepios lies on the Argolid plain, with Mt. Arachnaio and Mr. Titthion to the north. The former was said to have been a home of Zeus and Hera, and the latter, whose gentle slopes lead down to the plain, was said to have been where Asklepios was born.

To the south of the sanctuary is Mt. Kynortion, where there was a shrine to Apollo, Asklepios’ father, and farther to the south are the wooded slopes of Mt. Koryphaia, where the goddess Artemis is said to have wandered.

This is a land of myth and legend, a world of peace and healing, green and mild, dotted with springs. The sanctuary was actually called ‘the sacred grove’.

Asklepios, as a god of healing, was worshiped at Epidaurus from the 5th century B.C. to the 4th century A.D. According to archaeologist Angeliki Charitsonidou, it was the sick who turned to Asklepios, people who had lost all hope of recovery – the blind, the lame, the paralyzed, the dumb, the wounded, the sterile – all of them wanting a miracle.

But who was Asklepios?

Some believed he learned medicine from the famous centaur, Cheiron, in Thessaly. Another tale from the Homeric ages makes Asklepios a mortal man, a king of Thessaly, whose sons Machaon and Podaleirios fought in the Trojan War, and who learned medicine from their father.

Eventually, it came to be believed that Asklepios was a demi-god, born of a union between Apollo and a mortal woman. His father was also a god of healing and prophecy, both of which went hand-in-hand in the ancient world. The snake was a prophetic creature, and a creature of healing, so it is no wonder this animal came to be associated with Asklepios and medicine.

At Epidaurus, snakes were regarded as sacred, as a daemonic force used in healing at the sanctuary. These small, tame, blondish snakes were so revered that Roman emperors would send for them when in need.

The thing about Asklepios was that he was said to know the secret of death, that he had the ability to reverse it because he was born of his own mother’s death. Zeus, as king of the gods, believed that this went against the natural order, and so he killed Asklepios with a bolt of lightning.

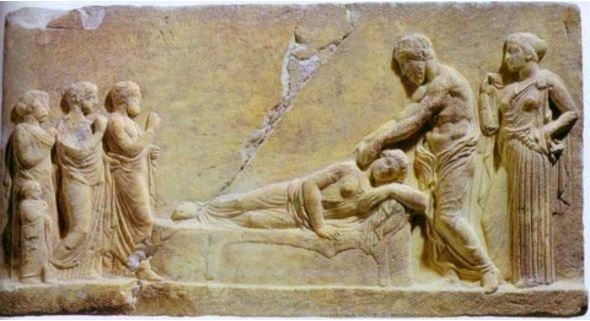

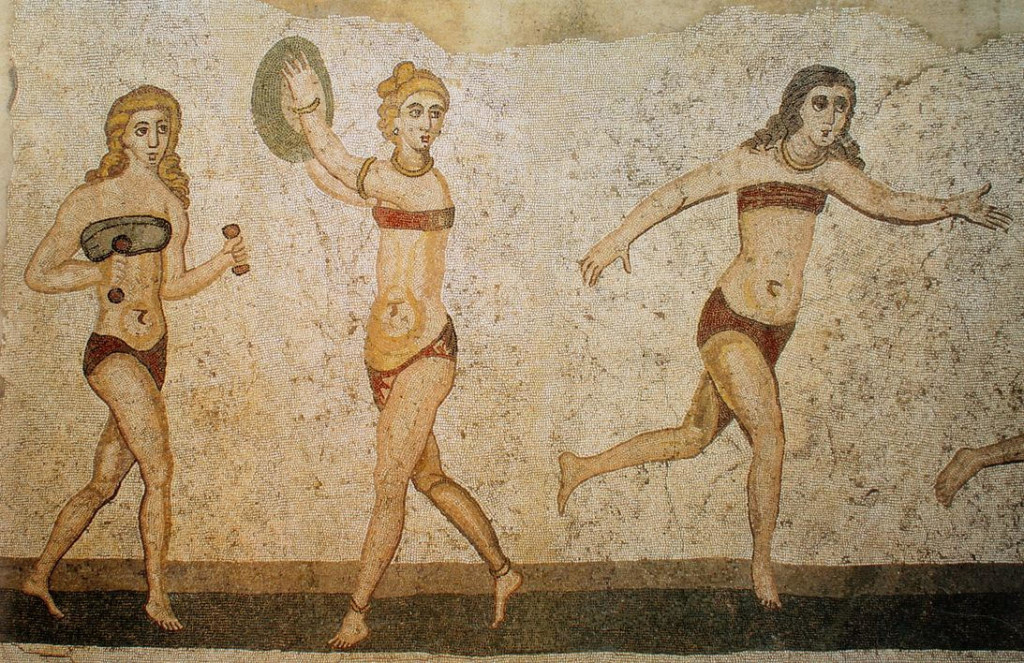

There are no written records of medical interventions by the priests of Epidaurus in the early centuries of its existence. The healing that occurred was only through the appearance of the god himself. However, over time the priesthood of Epidaurus began to question patients about their ailments, and prescribe routines of healing or exercise that would carry out the instructions given to pilgrims by Asklepios in the all-important dreams, the enkoimesis, which they had in the abato of the sanctuary.

It is quite a feeling to walk the grounds of the sanctuary at Epidaurus, to be in a place where people believed they had been touched or aided by a god, and actual miracles had occurred and were recorded.

Faith and the Gods are a big part of ancient history, and cannot be separated from the everyday. I’ve always found that I get much more out of a site, a better connection, when I keep that in mind. You have to remove the goggles of hindsight and modern doubt to understand the ancient world and its people.

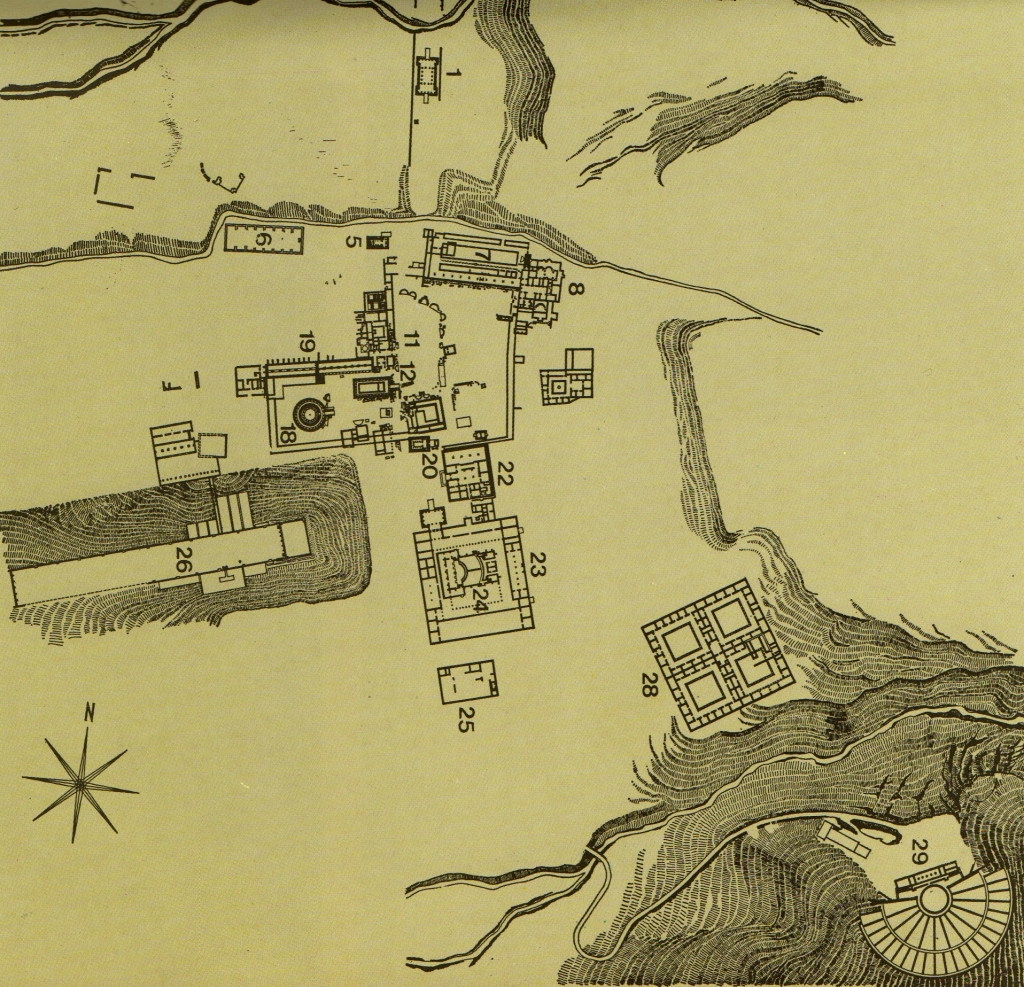

From the museum we walked past the ruins of the hospice, or the ‘Great Lodge’, a massive square building that was 76 meters on each side, two-storied, and contained rooms around four courtyards. This is where later pilgrims and visitors to the sanctuary and the games that were held in the stadium there would stay.

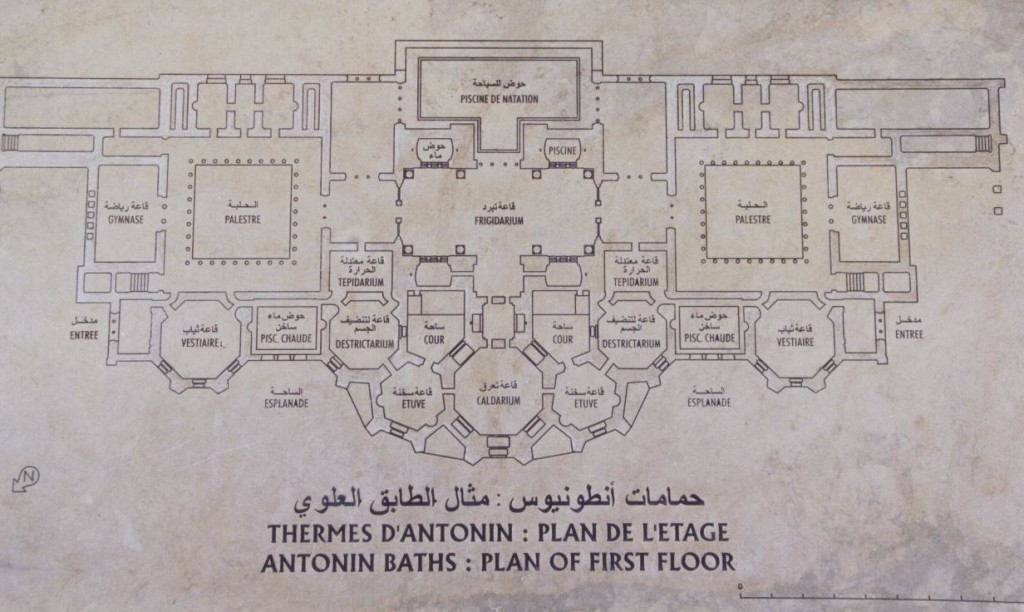

Map of the Sanctuary (from the site guide book) – 1 is the Propylaia; 12 the Temple of Asklepios; 18 the Tholos; 20 the Temple of Artemis; 19 the Abato

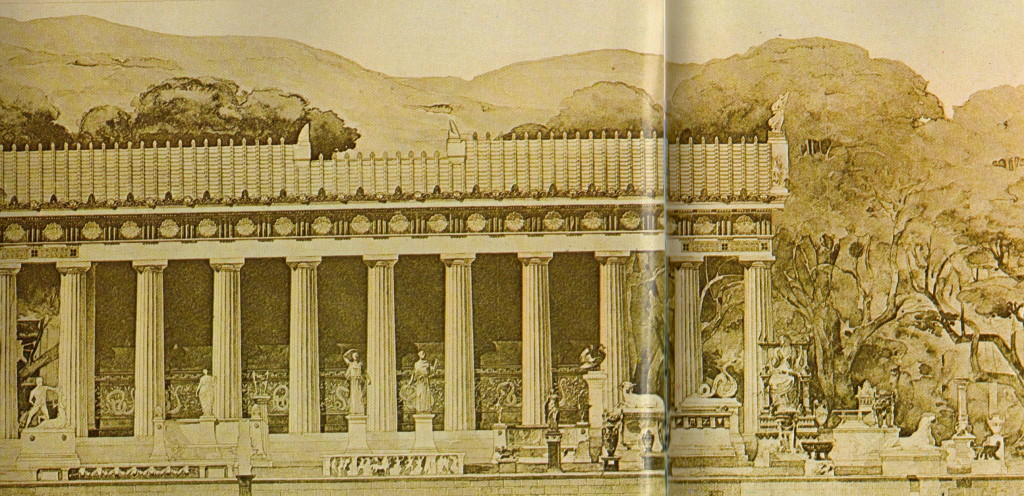

Without a map of what you are looking at, it’s difficult to pick out the various structures. Most of the remains are rubble with only the foundations visible. This sanctuary was packed with buildings, and apart from a few bath houses, a palaestra (22), a gymnasium (23), a Roman odeion (24), the stadium (26) and a large stoa (7), there are some ruins that one is drawn to, notably the temples.

I’m not sure why temples, among all those other ruins, are such a draw. Perhaps it is the mystery that surrounds them? Maybe it’s the fact that they were the beating heart of ancient sanctuaries where, for centuries, the devout focussed their energies?

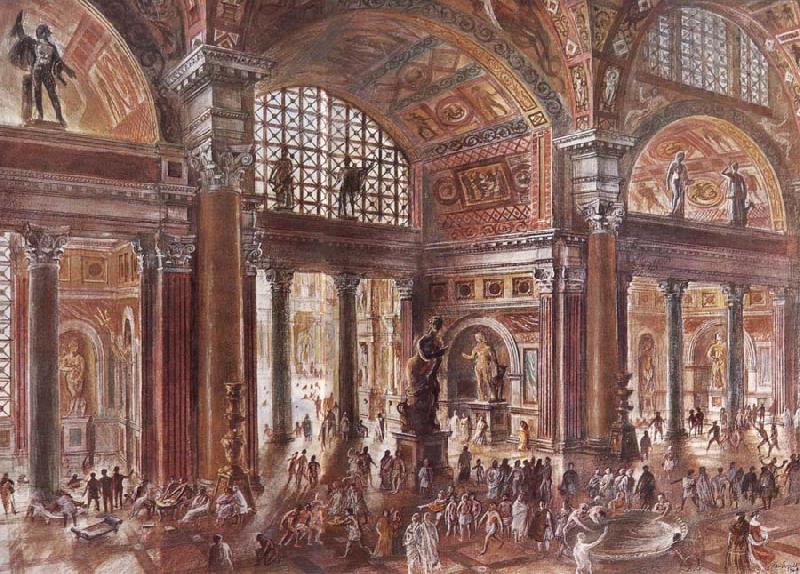

The sanctuary of Asklepios has several temples the largest being dedicated to the God of Healing himself, within which there stood a large chryselephantine statue of Asklepios.

There were also temples to Artemis (the second largest on-site), Aphrodite, Themis, Apollo and Asklepios of Egypt (a Roman addition), and the Epidoteio which was a shrine to the divinities Hypnos (sleep), Oneiros (Dream), and Hygeia (Health). These latter divinities were key to the healing process at Epidaurus.

As I sit at my desk writing this post on a chilly November evening, fighting my first cold of the season, I’m warmed by my memories of the sanctuary – the sunlight, the heat, the fresh air, the sight of green trees with a backdrop of mountains with the sea not far beyond.

That’s the type of place ancient Epidaurus was, and still is; a sacred escape where the mind, body, and soul could recuperate. It still feels like that, even in memory.

As the cicadas yammered on in their bucolic frenzy, and bees and butterflies wended their way among the fallen pieces of the ancient world, our feet crunched along on the gravel pathway, past the ruins of the palaestra, gymnasium, and odeion to an intersection in the sacred precinct of the sanctuary.

I looked down at my map and found that I stood with the temple of Artemis to my right as I faced the ruins of what was the magnificent temple of Asklepios to the north. You can see the foundations, the steps leading up.

The image of Asclepius is, in size, half as big as the Olympian Zeus at Athens, and is made of ivory and gold. An inscription tells us that the artist was Thrasymedes, a Parian, son of Arignotus. The god is sitting on a seat grasping a staff; the other hand he is holding above the head of the serpent; there is also a figure of a dog lying by his side. On the seat are wrought in relief the exploits of Argive heroes, that of Bellerophon against the Chimaera, and Perseus, who has cut off the head of Medusa. (Pausanias on Epidaurus – from the Description of Greece; Book 2.27.2)

I wondered how many pilgrims, how many people in need had walked, limped or crawled up those steps seeking the god’s favour.

I turned to my left to see a large, flat area of worn marble that was once the great altar of Apollo where pilgrims made blood sacrifices to Apollo and Asklepios in the form of oxen or cockerels, or bloodless offerings like fruit, flowers, or money.

Standing there, you can imagine the scene – smoke wafting out of the surrounding temples with the strong smell of incense, the slow drip of blood down the sides of the great altar, the tender laying of herbs and flowers upon the white marble, all in the hopes of healing.

As people would have stood at the great altar, they would have seen one of the key structures of the sanctuary beyond it, just to the west – the Tholos.

The Tholos was a round temple that was believed to be the dwelling place of Asklepios himself. It was here that, after a ritual purification with water from the sanctuary, that pilgrims underwent some sort of religious ordeal underground in the narrow corridors of a labyrinth that lay beneath the floor of the Tholos’ cella, the inner sanctum.

After their ritual ordeal, pilgrims would be led to the abato, a long rectangular building to the north of the Tholos and temple of Asklepios.

The abato is where pilgrims’ souls would be tested in by away of the Enkoimesis, a curative dream that they had while spending the night in the abato.

I have to admit that on previous visits to Epidaurus, I had by-passed the abato, this crucial structure where the god is said to have visited and healed pilgrims. This time, however, I went into the remains (which have been partially restored), and stood still for a while.

Miracles happened in this place, and there are over 70 recorded inscriptions that have survived which detail some of them – mute children suddenly being able to speak, sterile women conceiving after their visit to sanctuary, a boy covered in blemishes that went away after carrying out the treatment given to him by Asklepios in a dream. There are many such stories that have survived, and probably many more than that we do not know of.

As I stood in the abato, careful not to step on any snakes that may have been hiding along the base of the walls, I reflected on the examples of healing on the posted placard. It seemed that the common thread to all the dreams that patients had was that Asklepios visited them in their dreams and, either touched them, or prescribed a treatment which subsequently worked.

For a moment, I had my doubts, but then I remembered where I was, and for how many thousands of years people had been coming to this sanctuary for help, and had been healed.

Sleep. Dream. Health.

When I think of those divinities who were also worshiped at Epidaurus, right alongside Asklepios, it doesn’t seem so far-fetched. In fact, standing there, in that place of peace and tranquility, it seemed highly likely.

The people mentioned on the votive inscriptions – those who left vases, bronzes, statues, altars, buildings and fountains as thank offerings to the god and his sanctuary for the help they received – those people were real, as real as you or I. They confronted sickness, disease, and worry, just as we do.

Today, some people turn to their chosen god for help when they are in despair. Others turn to the medical professionals whom they hope have the skill and compassion to cure them.

At ancient Epidaurus, people could get help from both gods and skilled healers, each one dependent on and respectful of the other.

As we walked back to our car, the sun now dipping orange behind the mountains to the west, I thought about how special this place was, how the voices of Epidaurus, its sanctuary, and its great theatre, will never die or fade.

Indeed, just as Asklepios was said to have done, this is a place that defies death.

As we drove away, I found myself looking forward to my next return visit, and the new things that I will discover.

Thank you for reading.

Here is a short video I shot on-site. The quality is not great (that hot wind!), but it will show you a couple of the ruins I talked about above from where I was standing in front of the great altar of Apollo. The columns beyond the long rectangle of the temple of Asklepios belong to the abato.

Video Player

00:00

00:00