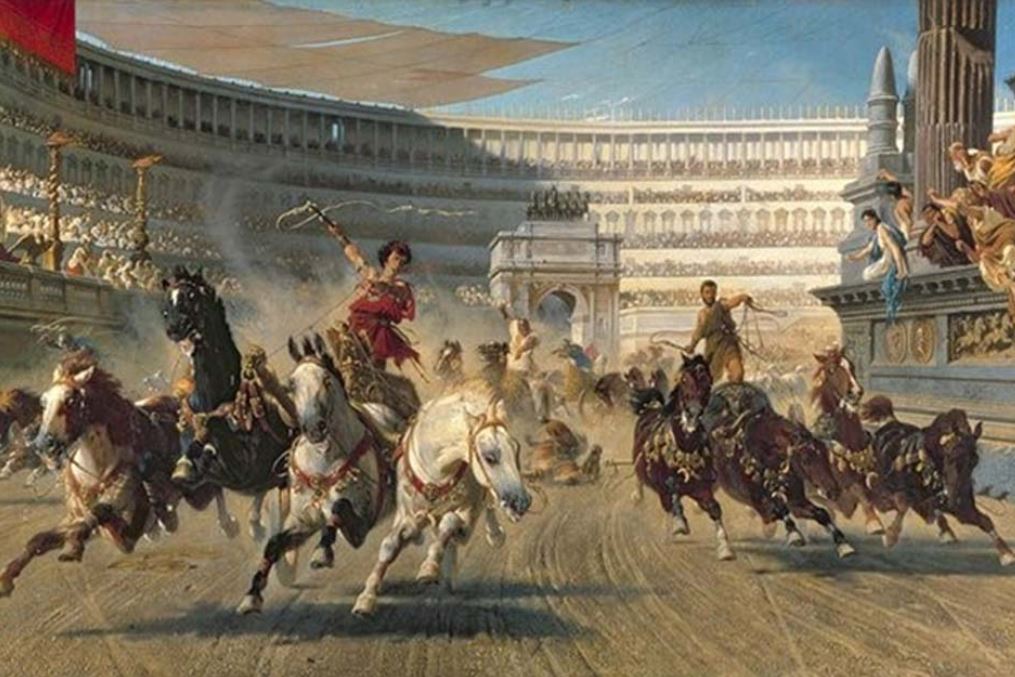

See you not, when in headlong contest the chariots have seized upon the plain, and stream in a torrent from the barrier, when the young drivers’ hopes are high, and throbbing fear drains each bounding heart? On they press with circling lash, bending forward to slacken rein; fiercely flies the glowing wheel. Now sinking low, now raised aloft, they seem to be borne through empty air and to soar skyward. No rest, not stay is there; but a cloud of yellow sand mounts aloft, and they are wet with the foam and the breath of those in pursuit: so strong is their love of renown, so dear is triumph. (Virgil, Georgics III-IV)

When we think of the raucous world of sport in ancient Rome, the images we conjure are most often of blood-soaked gladiatorial combat, or of chariot racing.

Today, we might think that gladiatorial combat was the most popular sport amongst the people of Rome, but in truth, nothing was more sensational than the chariot races put on in the great circus of Rome – the Circus Maximus.

In this post, we’re going to take a brief look at the circus itself, the charioteers, the horses, the fans, equipment, and what teams stood to win…and lose.

Their temple, dwelling, meeting-place, in fact the centre of all their hopes and desires, is the Circus Maximus. (Ammianus Marcellinus on Plebs and the Circus, XXVIII.4)

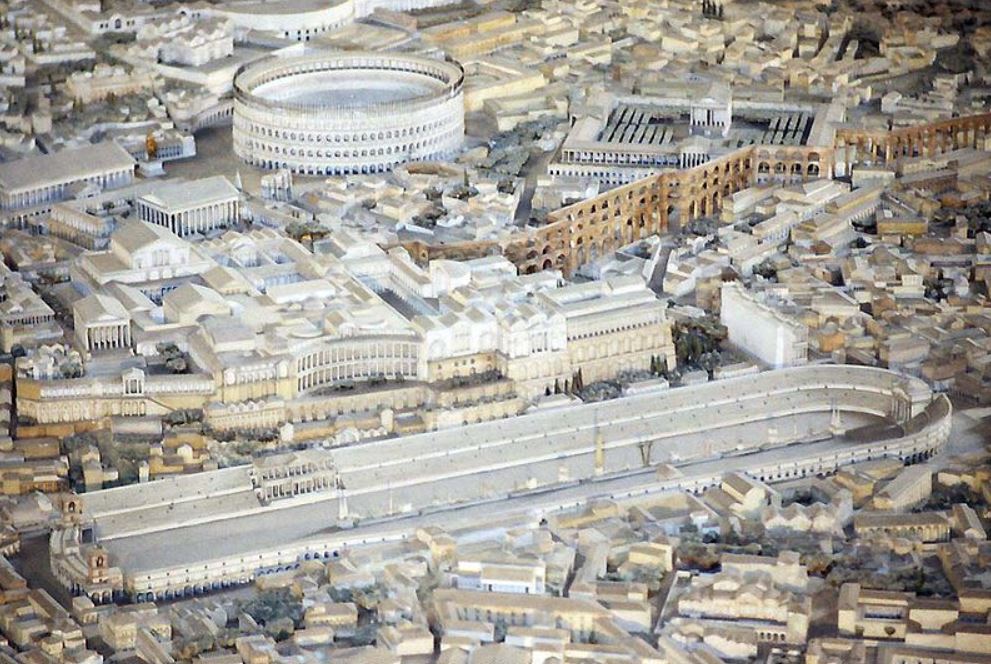

Chariot racing was an ancient sport handed down from the Greeks to the Etruscans and Romans early in the history of Rome, the races in the city of Rome being held in a dip in the land between the Palatine and Aventine Hills. Over time, the Circus Maximus was built upon by successive senates and emperors, making it the largest in the Roman world.

Rome’s great circus had an area of 45,000 square meters, making it twelve times larger than the Colosseum, and it could hold at least 150,000 spectators. With the addition of temporary wooden seating, the capacity was said to have reached 250,000!

The Circus Maximus was the largest and most expensive entertainment venue in Rome. Buildings had been added to it from the fourth century B.C. onward, going from wood to stone, and a major renovation was done in the first century B.C. Before the Colosseum was built, the Circus Maximus also hosted gladiatorial combats, wild animal hunts, and other games.

The Circus Maximus certainly owns its name, for by the time of Emperor Trajan, it was about 550-580 meters long, and about 80-125 meters wide. At the start of the track, there were twelve carceres, starting boxes, with ostia (gates) from which the teams would shoot out and charge the first 170 meters toward the central spina, which divided the course and which is what the teams raced around. The spina was 335 meters in length and 8 meters wide, and at each end of it were metae, the turning posts which the riders sped around. The spina was also ornamented with statues of the gods, towering palms, and obelisks from Rome’s campaigns in Egypt.

There were also large frames on the spina with mechanisms with suspended dolphins and eggs to count down the laps for a race. The total distance of a race of seven laps was about 5,200 meters over the packed earth and gravel track.

When it came to putting on games, or ludi as they were known, in the Circus Maximus, hundreds of staff were required in addition to the aurigae, the charioteers themselves. There were stable boys, grooms, cartwrights, saddlers, doctors, veterinarians, men at each of the starting gates (which were each six meters wide in Rome), men to clear the debris after crashes, lap counters, musicians, and even performers between races usually comprised of riders or acrobats.

That’s a lot of people to keep things running, but it was worth it to those who put on the games, for the people of Rome loved their chariot teams.

One might think that fans usually cheered for their favourite charioteers, but in truth, Romans were fans of their favourite factions, or factiones as they were known. There were four chariot factions in Rome: the Veneti (Blues), the Prasini (Greens), the Russati (Reds) and the Albati (Whites).

The four chariot factions of Rome were managed by the domini factionis, the ‘faction masters’ who were usually men of the Equestrian class. They would have sought out potential charioteers, made deals with others, and generally seen to the running of the faction and its success. The domini factionis were similar to the lanista of a gladiatorial school, or ludus.

In Rome, the factions had their headquarters, the stabula factionum, which contained accommodation and stables, on the Campus Martius, but their breeding grounds and training camps were located in the countryside.

People were wild for their factions, and there could be violence between the followers of each. During a race, each faction could enter either one, two, or three separate teams so that a full race could comprise up to twelve chariot teams running at a single time.

But who were the men who drove the factions to victory or defeat? Who were the charioteers of Rome?

O Rome, I am Scorpus, the glory of your noisy circus, the object of your applause, your short-lived favourite. The envious Lachesis, when she cut me off in my twenty-seventh year, accounted me, in judging by the number of my victories, to be an old man.

(Martial, Epigrammata, LIII. Epitaph of the charioteer Scorpus)

Outside of Rome, in the hippodromes of distant provinces, it was possible for individual owners to enter teams or even race themselves, but in Rome’s circus, it was the factions who entered the teams, and the professional charioteers, the aurigae, who raced for each faction.

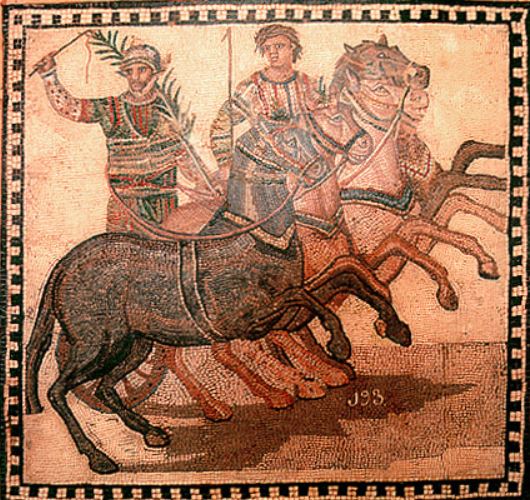

The aurigae were usually slaves or freedmen, low on the status scale the same as gladiators, but they could achieve great fame and wealth.

In his Epigrammata, the poet Martial tells us of a famed auriga named Scorpus who was one of the few charioteers to achieve the status of miliarius. The miliarii were those who had won over one thousand races – Scorpus was said to have won 2,048!

Ancient chariot racing in Rome was not dissimilar to modern sports. People were loyal to their faction, their ‘team’ so to speak, and charioteers, like pro sports players today, might be traded to or wooed by other factions. It was not uncommon for a charioteer to move factions several times before settling down in the latter half of his career.

Servants’ hands hold mouth and reins and with knotted cords force the twisted manes to hide themselves, and all the while they incite the steeds, eagerly cheering them with encouraging pats and instilling a rapturous frenzy. There behind the barriers chafe those beasts, pressing against the fastenings, while a vapoury blast comes forth between the wooden bars and even before the race the field they have not yet entered is filled with their panting breath. They push, they bustle, they drag, they struggle, they rage, they jump, they fear and are feared; never are their feet still, but restlessly they lash the hardened timber.

At last the herald with loud blare of trumpet calls forth the impatient teams and launches the fleet chariots into the field. (Sidonius Apollinaris, To Consentius)

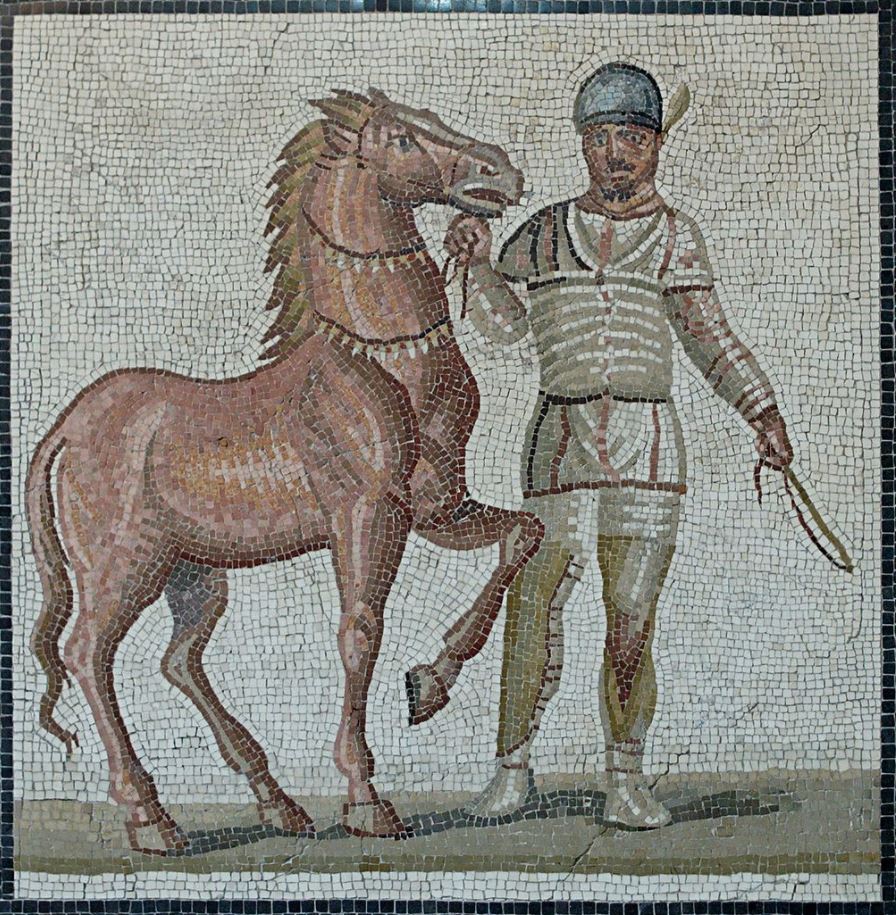

It wasn’t just the aurigae who achieved fame in the Circus Maximus. Horses too could be just as famous as their drivers, and oftentimes equine heroes were met with adoration.

Winning horses received palm branches, but also modii, which were measures of grain, with barley thrown into the mix. They were no doubt pampered back at the stabula factionum, and those horses who ran their factions to victory after victory enjoyed retirement in the countryside on a pension. They even received a burial with honour.

Race horses were bred and trained on private, and later imperial, stud farms, and the most successful breeds to race in the Circus Maximus were Lusitanos and Andalusian breeds from North Africa and Spain.

Though the horses were well-cared for by the factions, the racing was hard on their joints because of the tight turns of almost 180 degrees around the metae, and of course the great risk of injury.

Animal losses were high in the circus of Rome.

When it comes to the chariots and equipment used for the sport of chariot racing in ancient Rome, the movies have often been misleading.

In movies like Ben Hur (pictured above) the chariots are massive, some with long blades sticking out of the wheels. The chariots used in the movie made for some exciting film making and a great scene, but they were not at all accurate as far as what was really used.

Statue of a Roman biga (two-horse chariot) found in the Tiber. Note how much smaller the chariots actually were compared to what we see in the movies

Roman racing chariots, which were adapted from the ancient Greek and Etruscan chariots, were light-weight affairs, consisting of a slight wooden frame bound with strips of leather or linen, and small wheels with 6-8 spokes.

The most common chariot was the quadriga, a four-horse chariot from ancient Greece. The other commonly-used chariot was the biga, a Roman two-horse chariot. These two types were what were raced most often in the Circus Maximus in Rome. However, there were said to have been six-horse chariots (seiugae), eight-horse chariots (octoviugae), and even a ten-horse chariot (decemiugae).

Unfortunately, no remains of an imperial Roman chariot have been found, so we are forced to rely on artwork for an idea of their appearance. However, the tombs of Etruscan nobility have yielded some two-hundred and fifty examples of chariots.

In ancient Greece, charioteers wore only a long chiton with a belt when they raced, but Roman and Etruscan aurigae wore a short chiton, a protective skull cap or leather helm, and a wide leather belt composed of many straps. They also wore linen or leather wrappings on their legs and carried a curved dagger on them.

Why did they carry a dagger?

Well, it wasn’t to attack each other during the races. The reason for the dagger was that unlike Greek charioteers who held the reins in their hands, Roman charioteers wrapped the reins around their waists in order to use their whole body to steer the team and have one hand completely free for the whip.

If they ever got into a naufragia, a ‘shipwreck’ as chariot accidents were called, the dagger was supposed to be used to cut oneself free of the reins that were wrapped about you. It certainly was a risk when driving a team of four horses up to 75 kms per hour while trying to cut off your opponents going into the turns and so on.

One thing’s for sure, Roman chariot racing was extremely dangerous, though perhaps not as hazardous to one’s life as gladiatorial combat.

Games, or ludi, were the highlight of the Roman calendar, and chariot racing in the Circus Maximus was always the main event. During imperial games, there were usually up to twenty-four races per day at Rome, and that could include up to 1,152 horses.

This was always an event on a titanic scale, and the people of Rome loved it!

People were fanatical about their factions, and the charioteers who risked their lives in the Circus Maximus must have felt near to gods when the adoration of the crowd shone full upon their faces.

Apart from the traditional victory palm, winning charioteers and their factions could receive massive fortunes for their success.

In Rome, prizes ranged from 15,000 to 60,000 sestercii per race! That’s far more than the annual pay for a legionary soldier who received about 900 sestercii per year during the early Empire.

One charioteer by the name of Gaius Appuleius Diocles was said to have won almost 1,500 races and when he retired at the age of forty-two, he had a fortune of 35.5 million sestercii!

I guess some things don’t change, as the salary of military personnel today is far outstripped by that of the average sports star.

It seems that those who are destined entertain us, whether a modern sports star or an ancient charioteer in the circus of Rome, are going to be raised above the average person in society. Victory brings great reward, it seems, and ancient Rome was no different in that respect.

Bread and circuses!

There’s a reason Juvenal wrote those words back in the first century A.D.

Thank you for reading