Salvete Romanophiles!

After a long hiatus from this blog series, we’re finally back with a new Ancient Everyday post!

As my own birthday approaches, I thought it would be fun to explore this topic on the blog. So, we’re going to be taking a brief look at how they celebrated birthdays in ancient Rome!

Let’s party!

Roman dinner party

The celebration of birthdays was different in ancient Greece compared to the world of Rome. In ancient Greece, the individual’s birthday was not celebrated so much as the monthly birthday of the various gods the Greeks worshipped. Even today in Greece, the celebration of ‘name days’, that is, the saints’ days, is more widespread.

People may forget a birthday, but everyone remembers a name day!

However, apart from the religious connection, the celebration of birthdays in ancient Rome was quite different to that in ancient Greece.

So, what about birthdays in ancient Rome? Did they celebrate them?

The short answer is, ‘yes’, they did.

Birthdays, or dies natales, were indeed important celebrations.

But how did they celebrate? What did they do to celebrate? Did they give gifts?

The Roman Forum (by Becchetti)

In ancient Rome there were, in fact, two types of birthday celebrations: public and private.

Public birthdays were celebrations in honour of particular gods or the founding of temples or cults dedicated to those gods. There were also celebrations of the birthdays of cities.

For the present, though I believe everything finds its way to you in the letters of your friends, or even by messengers and rumour, yet I will write briefly what I think you would like to learn from my letters above all others. On the 4th of August I started from Dyrrachium, the very day on which the law about me was carried. I arrived at Brundisium on the 5th of August. There my dear Tulliola met me on what was her own birthday, which happened also to be the name-day of the colony of Brundisium and of the temple of Salus, near your house. This coincidence was noticed and celebrated with warm congratulations by the citizens of Brundisium.

(Cicero, Letter LXXXIX (a iv,1) To Atticus)

The above quote from Cicero’s letter to his friend, Atticus, is said to be one of the earliest known mentions of the natales of cities and temples, in this case the celebration of the Roman temple of Salus, the Goddess of Safety and Welfare, and the city of Brundisium, both of which are celebrated on the exact same day as his own daughter’s birthday.

We will talk about private birthdays shortly, but it is important to note that because Roman religion had so many deities, genii and numina (spirits) etc. to be honoured, it was common to have one’s private birthday on the same days as those public birthdays.

Some examples of major public birthdays included the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, the birthday of the Unconquerable Sun, around December the 25th, and the Dies Natalis Urbis Romae, the birthday of the founding of the city of Rome, on April the 21st, an event which is still celebrated today as the Natale di Roma with a parade, games and other events.

Natale di Roma parade (photo: Giampiero Giustarini)

In 2022, Rome will be celebrating its 2775th birthday. Happy Birthday Roma!

During the Principate, or the imperial period, another form of public birthday was the annual celebration of the birthdays of emperors and imperial family members, past and present. During these celebrations, the public made offerings and carried out rituals to commemorate their imperial overlords, or the days of their accession to the throne. The latter celebrations were known as the natales imperii.

Relief of Emperor Hadrian being greeted by the Goddess Roma and Genii of the Senate

Come, let pious Rome mark the birthday of eloquent Restitutus: Let every tongue be reverent; let all prayers be favourable. We are performing birthday rites; let litigation cease.

(Martial, Epigrams 10.87.1-4)

Unlike today, it seems that religion and birthdays were inevitably linked in the world of ancient Rome. Individuals, and their celebrants, commemorated the anniversary of the religious cult or genius with which their birthday was associated.

Good Genius, take the incense willingly, and willingly grant his prayers, so long as he burns when he thinks of me. But if by any chance he now sighs over another love, then, holy one, desert the faithless altar, I pray.

(Albius Tibullus, 4.5.9-12)

It really was an interesting commingling of religion and celebration.

But what about private birthday celebrations? Were they very different from today?

In some ways yes, and in other ways not so much.

Obviously, for most people today, religious rituals, such as those described above, are absent from the average birthday celebration.

However, when it came to the private birthday celebrations of men and women, family members and friends, there are some things which we have in common with the Romans.

A Cake for an Emperor!

(This is an actual cake created by talented Athenian artist Anne Maria Papadeli. Check out her work on Instagram @anne_marie_papadeli )

In ancient Rome, especially among the wealthy, those for whom we have sources, banquets were held and gifts were given. The Roman playwright, Terence, even describes how costly gift-giving could be! The servant, Davus, speaks:

Geta, my very good friend and fellow-townsman, came to me yesterday. There had been for some time a trifling balance of money of his in my hands upon a small account; he asked me to make it up. I have done so, and am carrying it to him. But I hear that his master’s son has taken a wife; this, I suppose, is scraped together as a present for her. How unfair a custom!—that those who have the least should always be giving something to the more wealthy! That which the poor wretch has with difficulty spared, ounce by ounce, out of his allowance, defrauding himself of every indulgence, the whole of it will she carry off, without thinking with how much labor it has been acquired. And then besides, Geta will be struck for another present when his mistress is brought to bed; and then again for another present, when the child’s birthday comes; when they initiate him, too: all this the mother will carry off; the child will only be the pretext for the present.

(Terence, Phormio, Act I, Scene I)

There were likely a wide range of gifts, depending on the class and financial status of the individuals in question. This would have been a similar situation to Saturnalia and the giving of sigillaria during those ‘best of days’ in the Roman calendar.

Private birthdays in ancient Rome, it seems, could be quite as important to individuals, and those who cared for them, as they are today. Perhaps even more so because of the religious connection. The Gods were watching!

Here is a wonderful quote from the poet, Sextus Propertius, who wrote a love poem describing his hopes for the birthday of the object of his love and affection, Cynthia:

I wondered what the Muses had sent me, at dawn, standing by my bed in the reddening sunlight. They sent a sign it was my girl’s birthday, and clapped their hands three times for luck. Let this day pass without a cloud, let winds still in the air, threatening waves fall gently on dry land. Let me see no one sad today: let Niobe’s rock itself suppress its tears. Let the halcyons’ cries be silent, leaving off their sighing, and Itys’s mother not call out his loss.

And oh, you, my dearest girl, born to happy auguries, rise, and pray to the gods who require their dues. First wash sleep away with pure water, and dress your shining hair with deft fingers. Then wear those clothes that first charmed Propertius’ eyes, and never let your brow be free of flowers.

And ask that the beauty that is your power may always be yours, and your command over my person might last forever. Then when you’ve worshipped with incense at wreathed altars, and their happy flames have lit the whole house, think of a feast, and let the night fly by with wine, and let the perfumed onyx anoint my nostril with oil of saffron. Submit the strident flute to nocturnal dancing, and let your wantonness be free with words, and let sweet banqueting stave off unwelcome sleep, and the common breeze of the neighbouring street be full of the sound.

And let fate reveal to us, in the falling dice, those whom the Boy strikes with his heavy wings. When the hours have gone with many a glass, and Venus appoints the sacred rites that wait on night, let’s fulfil the year’s solemnities in our room, and so complete the journey of your natal day.

(Sextus Propertius, Elegies, Book III.10:1-32, Cynthia’s Birthday, trans. A.S. Kline)

Was Cynthia amused?

In fact, birthday poems, such as Propertius’ above, was a particular genre that emerged. Here is another example by Martial that speaks to the giving of gifts:

Let the hunter bring the hare, the farmer a young goat, the fisherman the spoils of the sea. if each one sends what he has, Restitutus, what do you think a poet with send to you?

(Martial, Epigrams, 10.87.17-20)

When it came to private birthdays, people celebrated with family and friends, and lovers.

They also celebrated the birthdays of their patrons, if they had any, and one such example comes to light in the form of a small ‘book’ that was given by the grammarian, Censorinus, to his patron, Quintus Caerellius, on the day of his birthday, c. A.D. 238.

But while other men honour only their own birthdays, yet I am bound every year by a double duty as regards this religious observance; for since it is from you and your friendship that I receive esteem, position, honour, and assistance, and in fact all the rewards of life, I consider it a sin if I celebrate your day, which brought you forth into this world for me, any less carefully than my own. For my own birthday gave me life, but yours has brought me the enjoyment and the rewards of life.

(Censorinus, De Die Natali 3.5-6)

It seems that one gave what one could, or was expert at, as birthday gifts.

However, though we know quite clearly that Romans celebrated birthdays, little is known of the actual practices on birthdays. What we do know is that birthdays were celebrated, gifts were given, and religious offerings were made in the household and at temples and shrines.

A sacrifice portrayed on a lararium, or family shrine, in Pompeii

Banquets or parties were also held. The same as today, various foods, cakes, and wine were also consumed as part of birthday celebrations.

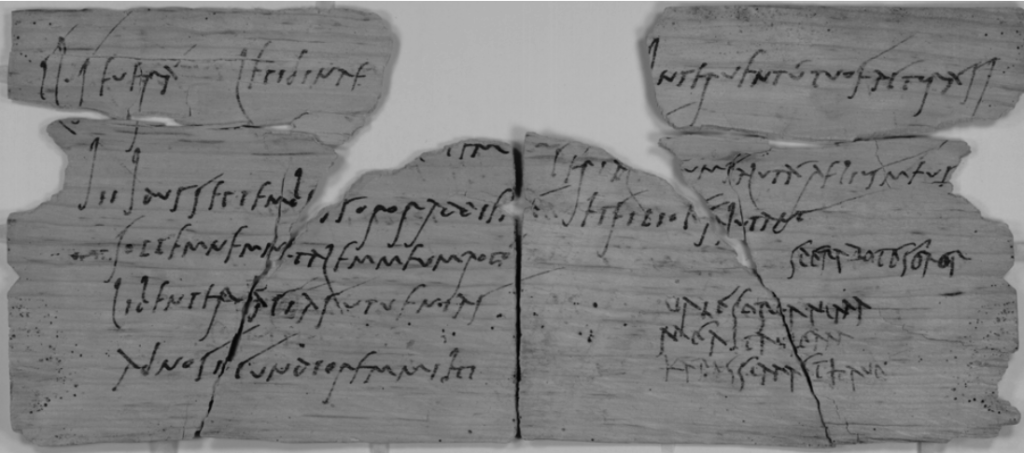

Perhaps one of the most wonderful examples we have of a birthday celebration is from one of the Vindolanda tablets, found along Hadrian’s Wall, which is actually a most sincere birthday party invitation from one woman to another:

Vindolanda Tablet. 291. Birthday Invitation of Sulpicia Lepidina, (romaninscriptionsofbritain.org)

Claudia Severa to her Lepidina greetings. On 11 September, sister, for the day of the celebration of my birthday, I give you a warm invitation to make sure that you come to us, to make the day more enjoyable for me by your arrival, if you are present. Give my greetings to your Cerialis. My Aelius and my little son send him their greetings. I shall expect you, sister. Farewell, sister, my dearest soul, as I hope to prosper, and hail.

(Vindolanda tablet #291, Birthday Invitation of Sulpicia Lepidina)

This artifact gives us a tantalizing and intimate look at the the role of birthdays in ancient Rome, or in this case, at the very edge of the Empire.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of birthdays in ancient Rome, however, is the almost symbiotic relationship between religion and the celebration of birthdays.

The following is a beautiful quote from Ovid in which the poet describes his own birthday celebration with the pious offering of cakes and prayers.

Thou awaitest, I suppose, thine honour in its wonted guise: a white robe hanging from my shoulders, a smoking altar garlanded with chaplets, the grains of incense snapping in the holy fire, and myself offering the cakes that mark my birthday and framing kindly petitions with pious lips.

(Ovid, Tristia 3.13)

In the world of ancient Rome, celebrating one’s own, or someone else’s birthday was not just about receiving visitors and gifts, or giving gifts and partying with friends at an excellent convivium.

To celebrate one’s birthday, or the birthday of someone else, was also the undertaking of a religious obligation that was to be expressed every year, through rituals and offerings.

Birthday rituals emphasized piety and sincerity, acknowledged the genius or god of that day, and they affirmed the bond between the person whose birthday it was, and those who cared for them.

That was a beautiful thing.

Thank you for reading.