inspiration

The Nine Muses – Creativity and the Higher Realm

And one day they taught Hesiod glorious song while he was shepherding his lambs under holy Helicon, and this word first the goddesses said to me – the Muses of Olympus, daughters of Zeus who holds the aegis: “Shepherds of the wilderness, wretched things of shame, mere bellies, we know how to speak many false things as though they were true; but we know, when we will, to utter true things.”

So said the ready-voiced daughters of great Zeus, and they plucked and gave me a rod, a shoot of sturdy laurel, a marvellous thing, and breathed into me a divine voice to celebrate things that shall be and things there were aforetime; and they bade me sing of the race of the blessed gods that are eternally, but ever to sing of themselves both first and last.

(Hesiod, Theogeny)

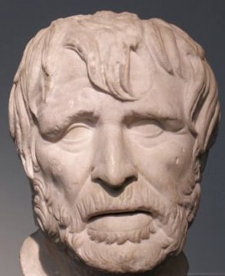

Hesiod

Sometime between the eighth and seventh centuries B.C. the poet Hesiod created his Theogeny, a work outlining the birth and genealogy of the Gods.

At the beginning of this epic poem, Hesiod talks about how, as a shepherd, he was caring for his flock on the slopes of Mt. Helicon, in the region of Boeotia. While there, Hesiod says that the Muses came to him and inspired him to create the Theogeny, a work that to this day provides the basis for ancient Greek religion.

Hesiod, before that, had not discovered his artistic self. He was a shepherd, the son of a farmer.

And yet, while on the slopes of this sacred mountain, the goddesses, the Muses, came to him and inspired him to bring forth his great work.

Mt. Helicon – 1829

Hesiod does not say he invented the contents of his work, or that he gathered existing tales from all over the Hellenic world.

The Gods gave him that song to sing. They inspired it in him, and he heard them.

We may scoff at this sort of thing today, our modern, media-driven minds too dense and distracted to hear anything beyond the ping of a mobile, but in the ancient world, and later ages of faith, the greatest artists and creators were those that paid attention to divine inspiration.

In the ancient Greek and Roman worlds, creativity and artistic endeavour were the realm of the Nine Muses, the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne, or ‘Memory’.

Tell me, Muse, the story of that resourceful man who was driven to wander far and wide after he had sacked the holy citadel of Troy. He saw the cities of many people and he learnt their ways. He suffered great anguish on the high seas in his struggles to preserve his life and bring his comrades home. But he failed to save those comrades, in spite of all his efforts. It was their own transgression that brought them to their doom, for in their folly they devoured the oxen of Hyperion the Sun-god and he saw to it that they would never return. Tell us this story, goddess daughter of Zeus, beginning at whatever point you will.

(Homer, The Odyssey)

There is a wonderful book that every creative person should read and re-read. It’s called The War of Art, by historical fiction author, Steven Pressfield. The book is about doing the things that you love and were meant to do without giving in to any excuses, or ‘Resistance’, as Pressfield calls the artist’s enemy.

Whenever I read The War of Art, Pressfield reminds me of something that I forget from time to time.

Creativity should never be taken for granted.

If you feel that there is something creative you want to do, or be, it is your sacred duty to do or become that. When you feel those urges, you have to fight ‘Resistance’ and rationalization with all of your might so that you can bring those things you were meant to create to fruition.

Those urges are the Muses speaking to you, telling you it’s time. If you ignore them, it’s to the detriment of your own soul.

Because when we sit down day after day and keep grinding, something mysterious starts to happen. A process is set into motion by which, inevitable and infallibly, heaven comes to our aid. Unseen forces enlist in our cause; serendipity reinforces our purpose.

This is the other secret that real artists know and wannabe writers don’t. When we sit down each day and do our work, power concentrates around us. The Muse takes note of our dedication. She approves. We have earned favor in her sight.

(Steven Pressfield, The War of Art)

Homer and his Guide – William Adolphe Bouguereau 1874

In ancient eyes, those who ignored the Gods didn’t do too well.

Hesiod and Homer knew that it was their duty to honour the Muses, they knew that they could not have created the works that they did without the goddesses’ help. Hubris was not a good thing in the ancient world.

But it was not just Hesiod and Homer who called on these goddesses for help. Throughout history, some of the greatest poets and other artists did so too.

Tell me, Muse, the causes of her anger. How did he [Aeneas] violate the will of the Queen of the Gods? What was his offence? Why did she drive a man famous for his piety to such endless hardship and such suffering? Can there be so much anger in the hearts of the heavenly gods?

(Virgil, The Aeneid)

Praxiteles’ Hermes and Dionysos

The artist who called on the Muses for aid and blessing was the one that was listening.

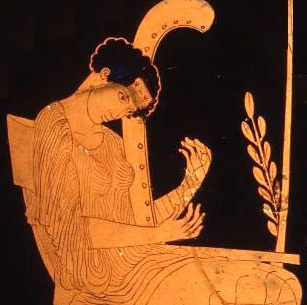

We know of writers and poets who have called on the Muses in their work because they have been written down, but I imagine that painters and sculptors would have done so too. What might Praxiteles have done before he broke the surface of a piece of marble? Or Michelangelo before he put his brush to the ceiling of the Cappella Sistina? What went through Mozart’s head before the first heavenly notes of his Clarinet Concerto in A major came to him? Just listen to it…

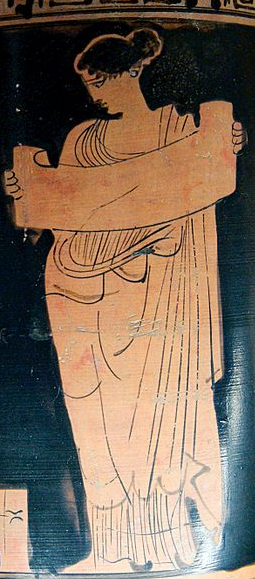

Before an ancient singer breathed those first notes, or before the lyre player plucked that first string at the Panathenaea or the Pythian Games, you can be sure that some inner prayer, conscious or unconscious, was sent up to their own Muse.

Apollo

You can also be sure that for the artist whose heart was open to this, the Muses spoke back.

…and I alone was there, Preparing to sustain war, as well Of the long way as also of the pain, Which now unerring memory will tell. Oh Muses! O high Genius, now sustain! O Memory who wrote down what I did see, Here thy nobility will be made plain.

(Dante, Inferno)

But who were the Muses? Early traditions said there were three, but that eventually turned to nine, and that is the number that has been given for ages. Their leader was Apollo, the God of Art, Light and Prophecy, and in this particular capacity he was known as ‘Apollo Mousagetes’, or ‘Apollo Muse-leader’.

Each one of these goddesses was responsible for a particular art form, and so, individual artists may have called on certain Muses. The names of these goddesses and their assigned art are as follows:

Calliope – Epic Poetry

Clio – History

Erato – Lyric Poetry

Euterpe – Song and Elegaic Poetry

Melpomene – Tragedy

Polyhymnia – Hymns

Terpsichore – Dance

Thalia – Comedy

Urania – Astronomy

I will begin with the Muses and Apollo and Zeus. For it is through the Muses and Apollo that there are singers upon the earth and players upon the lyre; but kings are from Zeus. Happy is he whom the Muses love: sweet flows speech from his lips. Hail, children of Zeus! Give honour to my song! And now I will remember you and another song also.

(Homeric Hymn to the Muses and Apollo)

Some of the arts assigned to the Muses might not seem like ‘art’ to us today – I’m thinking of Astronomy and History in particular. However, to the ancients, this made perfect sense. Astronomy involved philosophy and the understanding of the Heavens; it required great imagination and thought.

Mnemosyne by Gabriel Dante Rosetti

And History? Well, to me that is ‘Mnemosyne’. History is the record of human achievement in all areas, including art. History, poetry, and storytelling go arm in arm.

It must have been a humbling experience for ancient artists to know that the Muses were looking over their shoulders as they carried out the work they were inspired to do.

It must also have been a wonder-full experience to feel that, to know that you were not alone.

My hope is that we have not totally lost this today – artists, writers, athletes, inventors, creators of all kinds will find themselves in what we call ‘The Zone’. Many will thank ‘God’ for their successes, they will be exhilarated after a good session.

As a writer, I know that when I sit down and have a fantastic writing time, even after the worst of days, there must be something more at work. I feel like I’ve had help that day. I feel like I have done justice to the art that I love, and for that, I am grateful.

If you are a creator of something, anything, it behoves you to acknowledge the help that you have had, especially if that help is Heaven-sent.

O for a Muse of fire, that would ascend The brightest heaven of invention! A kingdom for a stage, princes to act, And monarchs to behold the swelling scene!

(William Shakespeare, Henry V)

Thank you for reading.

Facing Fear with the 300 Spartans

Hear your fate, O dwellers in Sparta of the wide spaces;

Either your famed, great town must be sacked by Perseus’ sons,

Or, if that be not, the whole land of Lacedaemon

Shall mourn the death of a king of the house of Heracles,

For not the strength of lions or of bulls shall hold him,

Strength against strength; for he has the power of Zeus,

And will not be checked till one of these two he has consumed.

Thus spake the the Oracle at Delphi, long ago, as recorded by Herodotus, the ‘father of history’, in Book 7 of The Histories. This was the prophecy that was given prior to the Greek stand at Thermopylae in which 300 Spartans and 700 men of Thespiae made one of the most heroic stands in the history of the world. Roughly one thousand Greek hoplites defended the pass known as the ‘hot gates’ (photo above) for three days against an army of about 1 million under Xerxes of Persia. This is a deed of heroism by which all others have been measured in western history ever since, and it echoes across the ages, unspoilt, radiant, despite politics and the greed of much lesser men.

Why is it that this single event in western history is revisited again and again? What do we get out of it today when our lives are so very different from those of 480 B.C.? There are probably several answers to that question, but for myself, it’s summed up in one word: Inspiration.

I know, “there he goes again, on about inspiration. Totally corny.”

Not to me. Inspiration, whether conscious or unconscious, is highly individualistic. I’ve stood on the battlefield of Thermopylae, and though there is a motorway running through it, and the sea has silted up for kilometers, the place casts a spell. It’s not the impressive modern monument to Leonidas of Sparta and his men that I find moving, but rather the little hillock on the other side of the road where the Spartans made their last stand, where they died for what they believed in, for their way of life.

It’s difficult for the modern mind to grasp this concept, no doubt, and out of misunderstanding, or perhaps fear, many might dismiss this as something that happened long ago. These men and their king volunteered for death, and they shall never be forgotten. They lived strongly, true to themselves. They’ve been celebrated through history to the modern age. Artists, filmmakers and yes, writers, have paid their tributes.

I remember seeing a picture of American troops in Afghanistan, sitting in the sand reading copies of Gates of Fire by Steven Pressfield (sadly, I couldn’t find the picture again to share with you). I think of what reading that book must have done for their morale; I can only guess, but I suspect that it inspired in them something of a will to fight on and face their fears. This is completely separate from the politics around our sad and current state of war and the reasons for it. There are few Leonidas’ in history.

I know I’ve written about this before, but Thermopylae has come to mind again as I’m reading a wonderful book by historian Michael Scott, entitled From Democrats to Kings: The Brutal Dawn of a New World from the Downfall of Athens to the Rise of Alexander the Great.

Scott’s book brings the world of ancient Greece after the Peloponnesian War into stark contrast with those days of honour and glory during the Persian invasion of Greece. It never ceases to blow my mind that a society (or polis, people, cultural group etc.) can achieve such magnificent glories, pleasing to the gods themselves, and then proceed with ease to piss it all away.

The make matters worse, Athens, Sparta, and Thebes each in their own turn, for years after, went to the Persians, cap in hand, to ask for aid in fighting their fellow Greeks! If there were any veterans of the Persian wars left, they must have been shaking their aging heads in shame at what was happening around them.

Maybe that is another reason the battle of Thermopylae is still celebrated. Not only was it a strategic and symbolic victory, it was also a selfless act. It was simple, and it was true. Leonidas ignored the politics that threatened to hold him back, and marched to certain death.

Many will say that this simply doesn’t apply to them, for they’re not soldiers fighting in a war on some foreign field. True, granted, though for many today, that is a reality. However, some past events, deeds, transcend all else, including war, and are applicable everywhere. We all face our own struggles day to day, and must meet whatever it is we must meet on our own, on our personal battlefields.

For a youth, that battle might be the fear of exams or being bullied in school. For an adult, it could be facing that daily commute to go to a job that is anything but inspiring. It might be not having a job at all, or failing to achieve one’s dreams or goals. A new mother may fear yet another day inside with the same routine, over, and over and over again. A family too may be dealing with the looming spectre of an allergy or something worse. However small and insignificant these things may seem, they are our own battles, fears, and it’s crucial that we fight on daily.

No doubt that Leonidas and his men each wrestled with some measure of fear, perhaps of loss, of not being remembered, of failing their way of life. But they overcame their fears, and though they died, they raised the bar of human achievement to heights we can only now dream of, but for which we should never cease to aim. And now, they grace our canvases, our screens, and our pages.

In closing, let the words etched upon the memorial stone at Thermopylae echo in our minds…

Ω ΞΕΙΝ ΑΓΓΕΛΛΕΙΝ ΛΑΚΕΔΑΙΜΟΝΙΟΙΣ ΟΤΙ ΤΗΔΕ ΚΕΙΜΕΘΑ ΤΟΙΣ ΚΕΙΝΩΝ ΡΗΜΑΣΙ ΠΕΙΘΟΜΕΝΟΙ

‘GO TELL THE SPARTANS PASSERBY,

THAT HERE OBEDIENT TO THEIR LAWS WE LIE’

Inspiring!

Thank you for reading.