Salvete, Readers and Romanophiles!

Welcome to this first post in our exciting new blog series The World of The Blood Road! In this nine-part series, we’re going to be taking a look at some of the history, people, and places that appear and provide the settings for this sixth book in the #1 best selling Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series.

If you’re a fan of the series, and don’t want any spoilers at all (such as where the story will lead you across the Empire), then you may wish to hold off until you’ve read the book.

However, if you just want to get stuck into the history and research that went into this novel, read on! We hope you enjoy it!

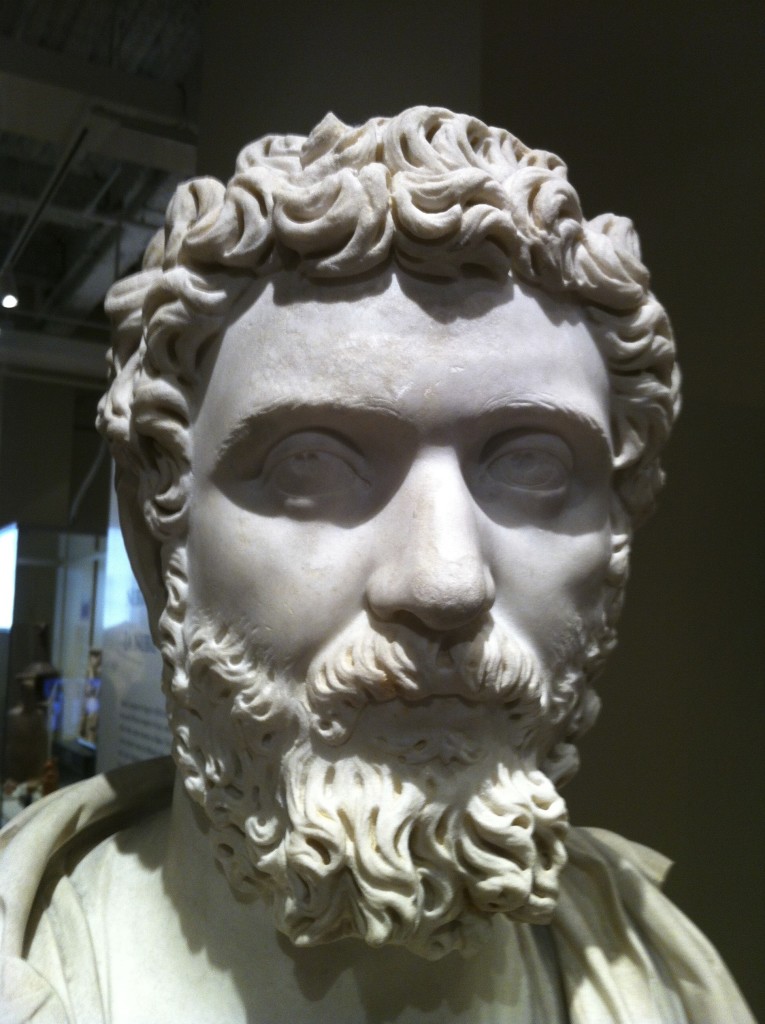

Emperor Caracalla

When we look at lists of Rome’s emperors, inevitably there are a few names that jump out at us because of their infamy and the brutality of their deeds. Emperors such as Caligula or Commodus might stand out to some. But, the beginning of the 3rd century A.D. is no less marred by the presence of another such Roman Emperor: Caracalla.

Fans of the Eagles and Dragons series will already be familiar with the bloody deeds which Caracalla may have perpetrated in Eburacum after the death of his father, Septimius Severus. If you missed the post on mass murder in Roman York, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

After the death of Severus, Caracalla and his brother, Geta, became co-emperors, and each of them hurried back to Rome separately to establish their own power at the heart of the Empire.

This tumultuous beginning to their reign is where The Blood Road begins.

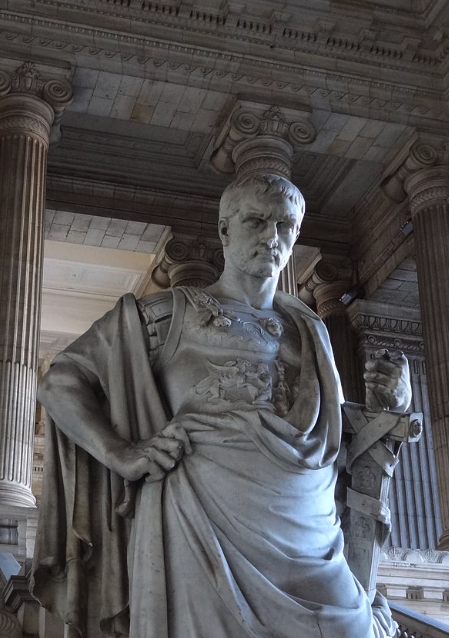

Septimius Severus

It could be said that Caracalla and Geta’s father, Septimius Severus, was the only great emperor of the Severan dynasty. However, even good emperors can have major flaws and, like Marcus Aurelius before him, Severus’ greatest flaw was, perhaps, that he trusted in his sons far too much.

One theory about the Caledonian campaign is that Severus saw it as a way to force his sons to mend their troubled ways and end their squabbling. But this did not have the intended outcome. As soon as Severus died, people braced themselves for the inevitable quarrel between the two brothers. Cassius Dio describes the scene in Rome when the two emperors returned from Caledonia:

As for his own brother, Antoninus had wished to slay him even while his father was yet alive, but had been unable to do so at the time because of Severus, or later, on the march, because of the legions; for the troops felt very kindly toward the younger brother, especially as he resembled his father very closely in appearance. But when Antoninus got back to Rome, he made away with him also. The two pretended to love and commend each other, but in all that they did they were diametrically opposed, and anyone could see that something terrible was bound to result from the situation. This was foreseen even before they reached Rome. For when the senate had voted that sacrifices should be offered on behalf of their concord both to the other gods and to Concord herself, and the assistants had got ready the victim to be sacrificed to Concord and the consul had arrived to superintend the sacrifice, neither he could find them nor they him, but they spent nearly the entire night in searching for one another, so that the sacrifice could not be performed then.

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, LXXVIII-1)

Rare bust of Geta in the Louvre (Wikimedia Commons)

There was even talk of ill-omens within the city, specifically one mentioned by Cassius Dio in which “two wolves went up on the Capitol, but were chased away from there; one of them was found and slain somewhere in the Forum and the other was killed later outside the pomerium. This incident also had reference to the brothers.”

In the middle of the tense stand-off between the two brothers was their mother, Julia Domna, who was constantly seeking to reconcile her sons, just as her husband had.

Julia Domna

When, according to Herodian, the brothers devised a pretence of dividing up the Empire that their father had worked so tirelessly to unite, Julia Domna pleaded with them:

As the brothers were now completely at odds in even the most trivial matters, their mother undertook to effect a reconciliation.

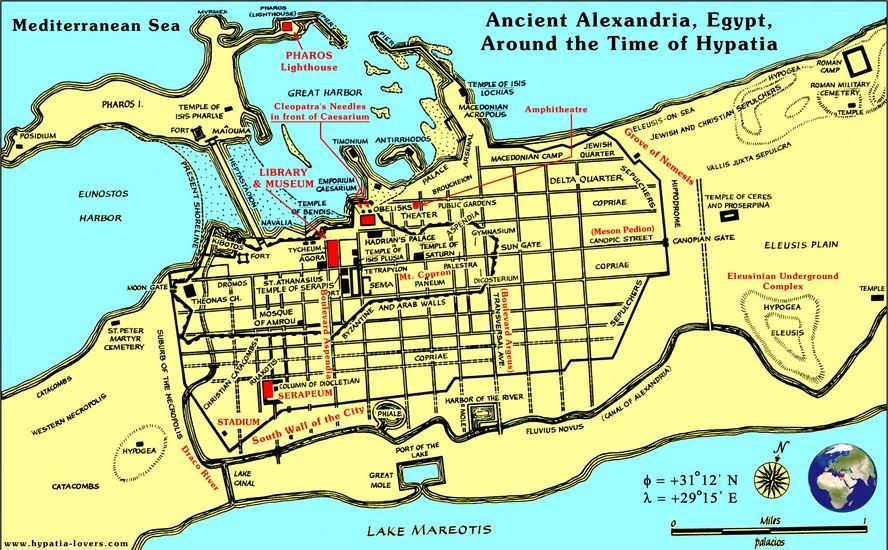

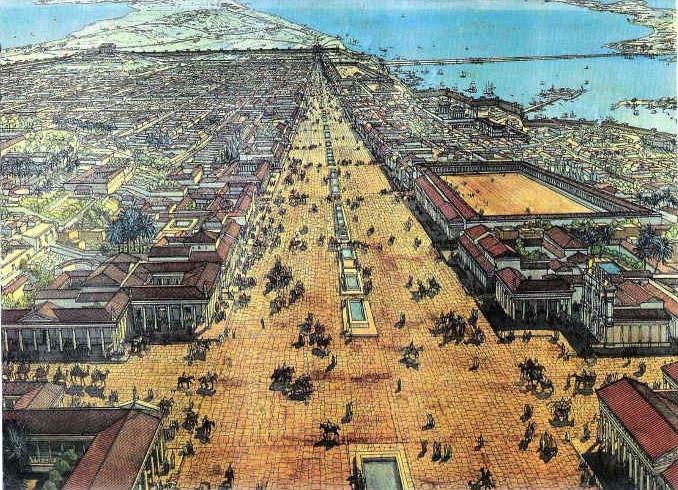

And at that time they concluded that it was best to divide the empire, to avoid remaining in Rome and continuing their intrigues. Summoning the advisers appointed by their father, with their mother present too, they decided to partition the empire: Caracalla to have all Europe, and Geta all the lands lying opposite Europe, the region known as Asia.

For, they said, the two continents were separated by the Propontic Gulf as if by divine foresight. It was agreed that Caracalla establish his headquarters at Byzantium, with Geta’s at Chalcedon in Bithynia; the two stations, on opposite sides of the straits, would guard each empire and prevent any crossings at that point. They decided too that it was best that the European senators remain in Rome, and those from the Asiatic regions accompany Geta.

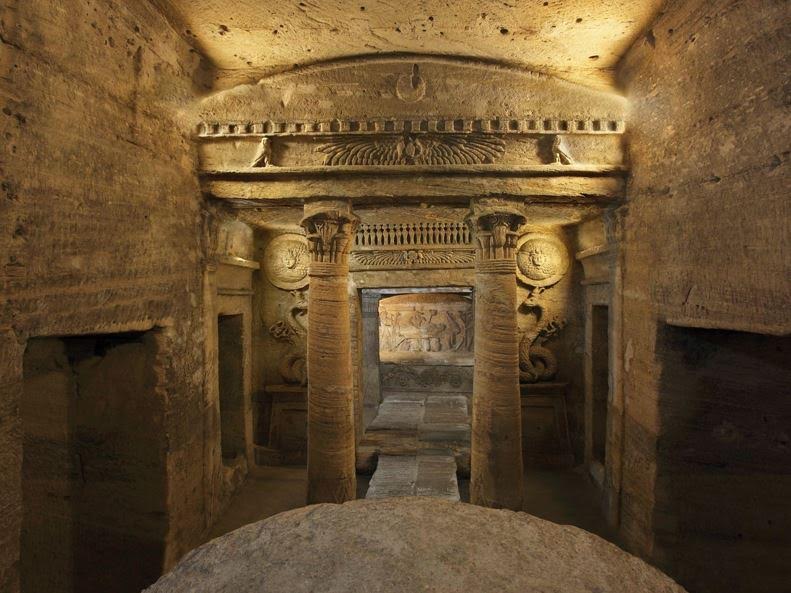

For his capital city, Geta said that either Antioch or Alexandria would be suitable, since, in his opinion, neither city was much inferior in size to Rome. Of the Southern provinces, the lands of the Moors, the Numidians, and the adjacent Libyans were given to Caracalla, and the regions east of these peoples were allotted to Geta.

While they were engaged in cleaving the empire, all the rest kept their eyes fixed on the ground, but Julia cried out: “Earth and sea, my children, you have found a way to divide, and, as you say, the Propontic Gulf separates the continents. But your mother, how would you parcel her? How am I, unhappy, wretched – how am I to be torn and ripped asunder for the pair of you? Kill me first, and after you have claimed your share, let each one perform the funeral rites for his portion. Thus would I, too, together with earth and sea, be partitioned between you.”

After saying this, amid tears and lamentations, Julia stretched out her hands and, clasping them both in her arms, tried to reconcile them. And with all pitying her, the meeting adjourned and the project was abandoned. Each youth returned to his half of the imperial palace.

(Herodian, History of the Roman Empire, 4.3)

Sadly, it seems the Goddess Concord turned her back on the situation, just as Caracalla and Geta had turned their backs on her. Rome’s ‘wolves’ were determined to destroy each other, and each was aware of plots against him. They both became obsessed and paranoid (perhaps rightly so) and as Herodian tells us: “They tried every sort of intrigue; each, for example, attempted to persuade the other’s cooks and cupbearers to administer some deadly poison. It was not easy for either one to succeed in these attempts, however: both were exceedingly careful and took many precautions. Finally, unable to endure the situation any longer and maddened by the desire for sole power, Caracalla decided to act…”

Palace of Septimius Severus, Palatine Hill, Rome (photo by Lasse Lofstrom; Trek Earth)

Throughout the history of Rome, there have been many heinous acts perpetrated by emperors, but what happened next is perhaps near the top of the list.

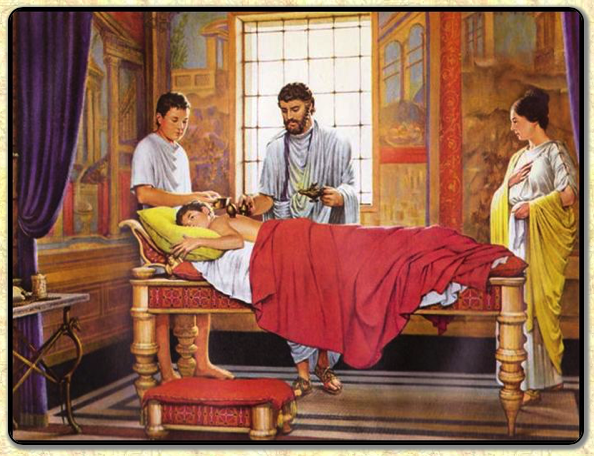

Frustrated by another failed attempt upon Geta’s life at Saturnalia in A.D. 211, Caracalla decided enough was enough:

Antoninus [Caracalla] induced his mother to summon them both, unattended, to her apartment, with a view to reconciling them. Thus Geta was persuaded, and went in with him; but when they were inside, some centurions, previously instructed by Antoninus, rushed in a body and struck down Geta, who at sight of them had run to his mother, hung about her neck and clung to her bosom and breasts, lamenting and crying: “Mother that didst bear me, mother that didst bear me, help! I am being murdered.” And so she, tricked in this way, saw her son perishing in the most impious fashion in her arms, and received him at his death into the very womb, as it were, whence he had been born; for she was all covered with his blood, so that she took no note of the wound she had received on her hand. But she was not permitted to mourn or weep for her son, though he had met so miserable an end before his time…she alone, the Augusta, wife of the emperor and mother of the emperors, was not permitted to shed tears even in private over so great a sorrow.

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, LXXVIII-2)

Geta Dying in his Mother’s Arms by Jacques-Augustin-Catherine Pajou, Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart, Germany (Wikimedia Commons)

Dio tells us that Caracalla ordered the centurions to murder Geta, and Herodian says that Caracalla did the deed himself. Either way, it seems that Geta bled to death in his mother’s arms.

Fratricide was highly frowned upon, and Caracalla knew that Geta had a lot of supporters among the people, the senators, and in the legions. Herodian tells us that he fled, under guard, to the Praetorian camp where he explained to the troops that he had escaped a plot against his life, and that the Gods had chosen him as sole emperor.

In gratitude for his deliverance and in return for the sole rule, he promised each soldier 2,500 denarii and increased their ration allowance by one-half. He ordered the praetorians to go immediately and take the money from the temple depositories and the treasuries. In a single day he recklessly distributed all the money which Severus had collected and hoarded from the calamities of others over a period of eighteen years.

When they heard about this vast amount of money, although they were aware of what had actually occurred, the murder having been made common knowledge by fugitives from the palace, the praetorians at once proclaimed Caracalla emperor and called Geta enemy.

(Herodian, History of the Roman Empire, 4.4)

After this bloody act, when he emerged from the protection of the Castra Praetoria with his guard, Caracalla set about securing his position as sole emperor with further acts of blood.

In a long series of proscriptions, with the legions and Praetorian Guard behind him, safely purchased with all of the funds he could muster, Caracalla set about eliminating anyone who could pose a potential threat, or even whisper a word against him:

Of the imperial freedmen and soldiers who had been with Geta he immediately put to death some twenty thousand, men and women alike, wherever in the palace any of them happened to be; and he slew various distinguished men…

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, LXXVIII-4)

Many perished with the beginning of Caracalla’s sole rule as emperor, and one wonders if he ever lived that down. His father’s past advice about securing the loyalty of the legions was, it seemed, the only thing that saved him, at least for a time. No matter one’s station, anyone with a passing connection to Geta was slain, and the list is a lengthy one, according to Herodian:

Geta’s friends and associates were immediately butchered, together with those who lived in his half of the imperial palace. All his attendants were put to death too; not a single one was spared because of his age, not even the infants. Their bodies, after first being dragged about and subjected to every form of indignity, were placed in carts and taken out of the city; there they were piled up and burned or simply thrown in the ditch.

No one who had the slightest acquaintance with Geta was spared: athletes, charioteers, and singers and dancers of every type were killed. Everything that Geta kept around him to delight eye and ear was destroyed. Senators distinguished because of ancestry or wealth were put to death as friends of Geta upon the slightest unsupported charge of an unidentified accuser.

He killed Commodus’ sister [Cornificia], then an old woman, who as the daughter of Marcus had been treated with honour by all the emperors. Caracalla offered as his reason for murdering her the fact that she had wept with his mother over the death of Geta. His wife [Plautilla], the daughter of Plautianus, who was then in Sicily; his first cousin Severus; the son of Pertinax; the son of Lucilla, Commodus’ sister [Pompeianus]; in fact, anyone who belonged to the imperial family and any senator of distinguished ancestry, all were cut down to the last one.

Then, sending his assassins to the provinces, he put to death the governors and procurators friendly to Geta. Each night saw the murder of men in every walk of life. He burned Vestal Virgins alive because they were unchaste. Finally, the emperor did something that had never been done before; while he was watching a chariot race, the crowd insulted the charioteer he favoured. Believing this to be a personal attack, Caracalla ordered the Praetorian Guard to attack the crowd and lead off and kill those shouting insults at his driver.

The praetorians, given authority to use force and to rob, but no longer able to identify those who had shouted so recklessly (it was impossible to find them in so large a mob, since no one admitted his guilt), took out those they managed to catch and either killed them or, after taking whatever they had as ransom, spared their lives, but reluctantly.

(Herodian, History of the Roman Empire, 4.6)

Despite the bloodbath, Caracalla was not yet finished with his brother, and what he did next was, perhaps, indicative of the extreme hatred he had for Geta.

Caracalla now sought to fully erase his brother Geta’s very existence from the historical record in an act that has come to be called, in modern times, damnatio memoriae, the ‘condemnation of memory’.

All across the empire Geta’s name was ordered to be struck from documents and his image erased or destroyed in paintings, statuary, upon monuments, and coinage. Anywhere Geta appeared, he was to be erased.

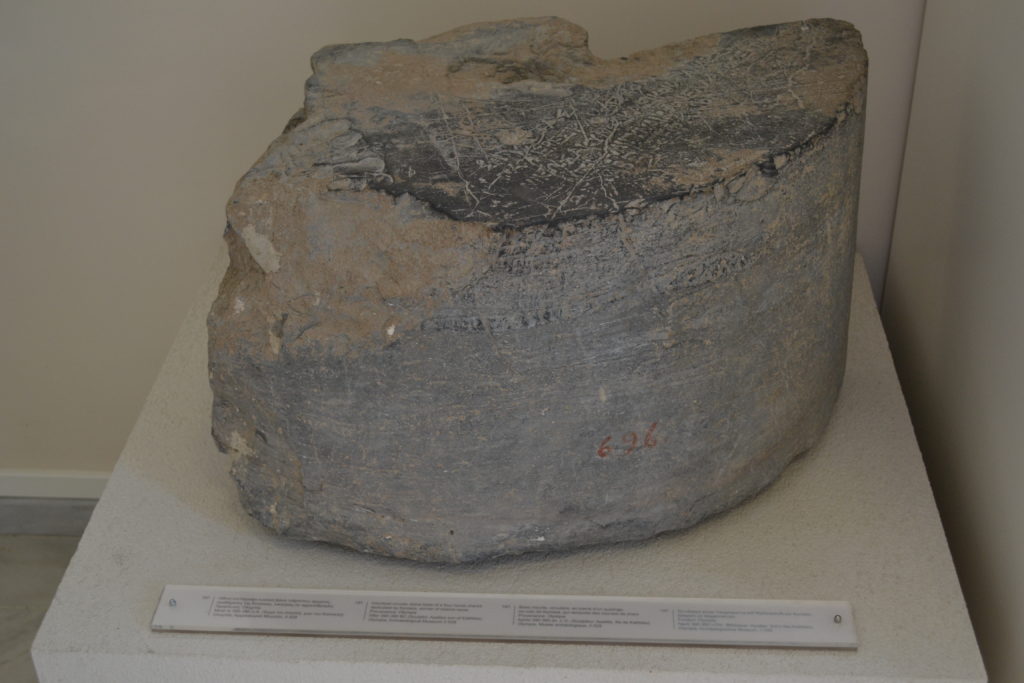

Portrait of the Severan family with Geta’s face erased.

Due to the bloody start to his reign, Emperor Caracalla’s infamy was now solidified. His survival was due mainly to the loyalty of the troops, but as we shall see later in this blog series, even that would last for a finite amount of time. Caracalla was not his father, Septimius Severus, and he would prove that to the world he was so desperate to rule. It would only be a matter of time before his enemies caught up with him.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this first post in The World of The Blood Road blog series. Stayed tuned for Part II in which we will look at travel and transportation in the Roman Empire.

The Blood Road is available on-line now in e-book and paperback at major retailers. CLICK HERE to get your copy. You can also buy direct from Eagles and Dragons Publishing for any device HERE.

If you are new to the Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series, you can check out the #1 best selling prequel, A Dragon among the Eagles for just 1.99 HERE.

Thank you for reading.