Welcome back to The World of The Dragon: Genesis. In our last post delving into he research for our latest historical fantasy novel, The Dragon: Genesis, we looked at the joint rule of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus. If you missed it, you can read it HERE.

In Part VI of this blog series, we’re going to be looking at one of the most brutal enemies Rome has ever had to face, an enemy that slipped past the frontiers and penetrated the heart of Rome itself.

We’re not talking about barbarian tribes north of the Danube frontier, or waves of Parthian cataphracts from the East. No, the most deadly enemy Rome had to contend with during the reign of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus was the plague.

And it almost completely destroyed the Roman Empire.

The ‘Antonine Plague’, as it is now known, began in A.D. 165 and lasted into the early 180s. It was the largest pandemic Rome had ever had to deal with to that point in its history.

This was an enemy that did not discriminate when it came to victims.

…after the victory over the Parthians, there occurred so destructive a pestilence, that at Rome, and throughout Italy and the provinces, the greater part of the inhabitants, and almost all the troops, sunk under the disease.

(Eutropius, Roman History, Book VIII)

Before we get into the few specifics of the Antonine Plague, we should first take a look at how Romans viewed disease, and what could have started a pandemic of these proportions.

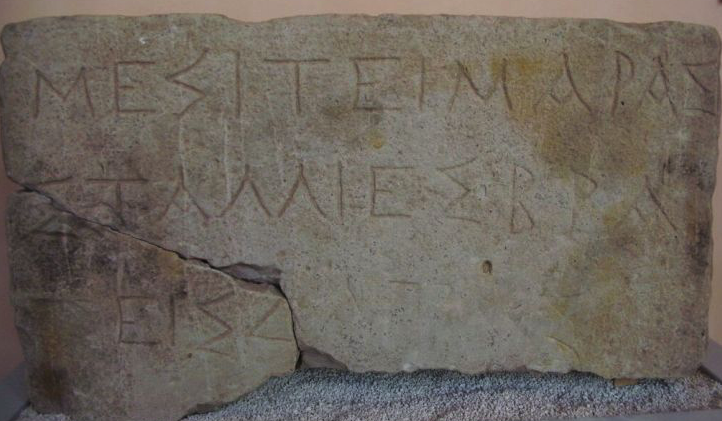

Inscription dedicated to Goddess Mefitis (from www.katherinemcdonald.net)

In the ancient world, Roman medical practices were a strange mixture of practical Greek methods and Roman religious beliefs.

Disease and plague were to be feared, and the gods who were associated with them were to be propitiated.

In the Roman world, it was believed that sulphurous fumes that came out of the earth could be responsible for epidemics and plagues. As a result, the Romans made offerings to the Mefitis, a goddess of sulphurous fumes and of plagues.

A cult of Mefitis began in the volcanic regions of central and southern Italy, and her main shrine was located in Samnite territory on the slopes of the volcano of Ampsanctus.

In Rome, there was a temple of Mefitis on the Esquiline hill, and at Cremona, in the North of Italy, there was a temple dedicated to the goddess of plagues just outside the city walls.

Fumes coming out of the earth… Mefitis’ domain.

In addition to offerings to the Goddess of Plagues and Fumes, the Romans also held games in the hopes that these – also an aspect of religion – would help them to avoid disease and keep this deadly enemy from their doors.

The Ludi Saeculares, or Secular Games (also known as the Tarentine Games) were held once every century with the intention that they would help Rome avoid pestilence.

The fist Secular Games were held by the consul Publius Valerius Poplicola in 509 B.C. at the altar of Dis and Proserpina located on the Campus Martius at a spot known as ‘Tarentum’, hence the other name of ‘Tarentine Games’.

In addition to sport, the games also included three days and three nights of stage plays.

One has to wonder how it was decided when the Ludi Saeculares were to take place, and details are sketchy about this. But, we do know of two other instances in which the games were held.

Remains of the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine Hill

In 17 B.C. the Emperor Augustus held the games which culminated in a ceremony at the temple of Apollo, on the Palatine hill, a temple Augustus built. Among other things, Apollo was a god of healing. (Those who have read Children of Apollo, will be familiar with this temple.)

The Ludi Saeculares were also held in A.D. 204 by none other than Septimius Severus who came out the winner in the civil war that followed the death of Commodus, Marcus Aurelius’ son and heir.

Severus’ games came in the wake of the Antonine Plague, so it is likely that after the devastation, it was believed the gods needed to be propitiated once more.

What might have been the causes of the spread of disease in ancient Rome?

There are several possibilities.

First of all, sewage and bad hygiene were a prime suspect.

When we think of ancient Rome, we tend to think of baths, running water, pristine white marble etcetera, but this is not entirely accurate. Despite the presence of running water and sewer systems, the truth was that many Romans did not have access to these things, especially in poorer neighbourhoods like the Suburra. In ancient Rome, most sewers were privately owned by the rich, and so, in the poor, tightly-packed neighbourhoods where tenement blocks rose up from the streets, often the only place to dump faeces, garbage and other waste was directly onto the street. With the preponderance of flies and dogs around all this filth, bacteria was everywhere.

Another reason why disease might have spread were the public baths.

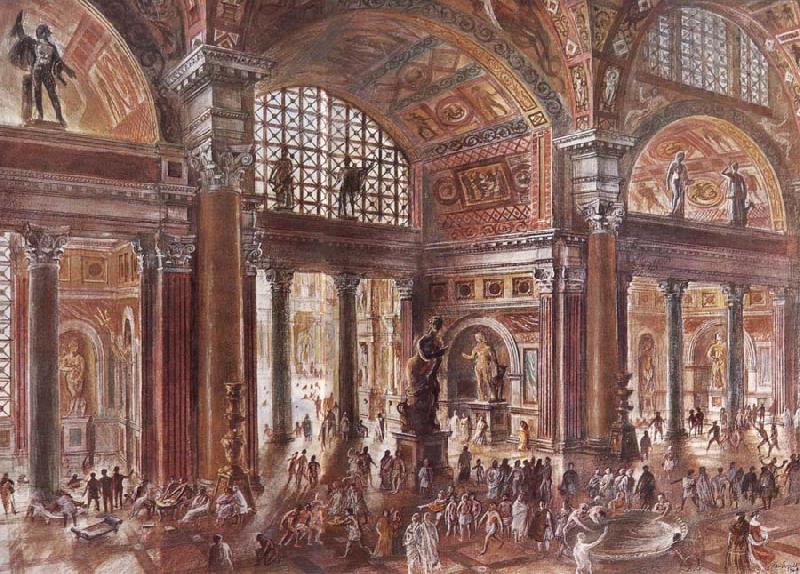

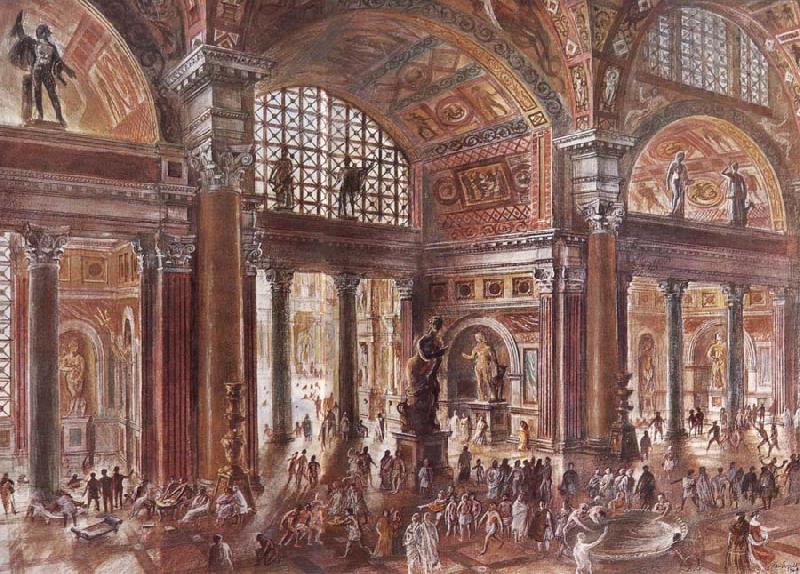

Baths of Diocletian (by unknown artist)

This seems contrary to what one might expect, but despite the Roman propensity for bathing and cleanliness, the hot water used in the baths of Rome and elsewhere was not cleaned chemically like today (using chlorine). As a result, bacteria would have thrived in the public baths.

Diet could also play a role in the spread of disease, especially as many Romans were malnourished. The diet of the average Roman consisted mainly of grains, distributed by the state. They had some vegetables and fruit, but meat was actually uncommon, and when they did have meat, there were no food standards to ensure freshness and quality. And so, food was often contaminated with parasites, as was the drinking water of most people.

Disease spread easily in densely populated areas, and as one of the most populous cities in the world at the time, Rome was especially vulnerable. This was certainly true in poorer neighbourhoods where many people shared small spaces, making the transmittal of disease easier.

The Antonine Plague was said to be transmitted through touch.

Lastly, another reason for the possible spread of plague and disease was deforestation around Rome and especially along the banks of the River Tiber. The clearing of trees led to the creation of rising water and an increase in the size of the marshes near Rome where mosquitoes and other carriers of diseases, such as malaria, flourished.

Coastal lagoon along shores of Lake Fogliano in the Pontine Plain – breeding ground for mosquitoes and diseases like malaria (Wikimedia Commons)

Part of the The Dragon: Genesis takes place during the Antonine Plague which began in A.D. 165.

This particular disease, however, did not originate in the city of Rome.

From A.D. 161-166, Emperor Lucius Verus was waging war against the Parthians in the East. While they were in Seleucia, a sickness began to spread among the troops of his legions, a sickness that they brought back with them to Rome and other parts of the Empire.

It was his [Lucius Verus] fate to seem to bring a pestilence with him to whatever provinces he traversed on his return, and finally even to Rome. It is believed that this pestilence originated in Babylonia, where a pestilential vapour arose in a temple of Apollo from a golden casket which a soldier had accidentally cut open, and that it spread thence over Parthia and the whole world. Lucius Verus, however, is not to blame for this so much as Cassius, who stormed Seleucia in violation of an agreement, after it had received our soldiers as friends. This act, indeed, many excuse, and among them Quadratus, the historian of the Parthian war, who blames the Seleucians as the first to break the agreement.

(Historia Augusta, The Life of Lucius Verus, 8)

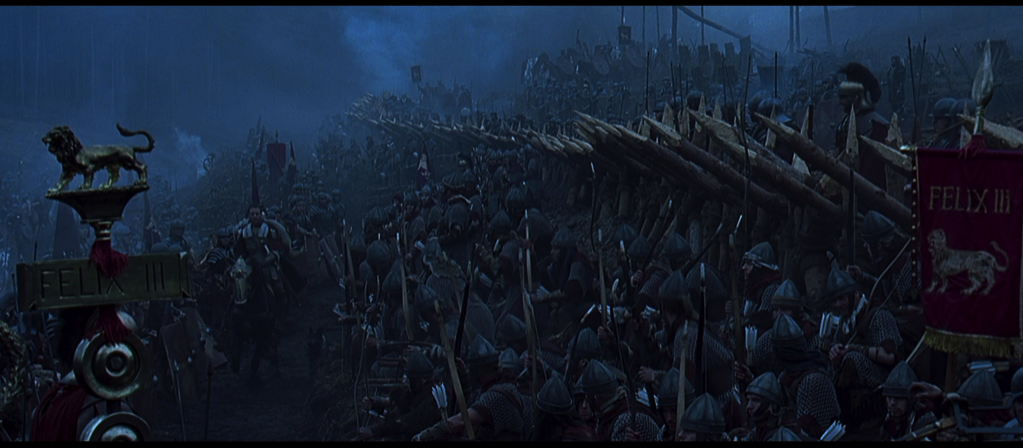

The troops return!

What little we know of the disease comes from the observations of the physician, Galen, who was called upon by Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus at the time, and who recorded some of his observations in scattered texts, including his Methodus Medendi.

From Galen’s descriptions, it is thought today that the Antonine Plague was an outbreak of small pox. The symptoms included severe fever, diarrhea, pharyngitis, and on the ninth day of the illness, the appearance of skin eruptions (boils or pustules).

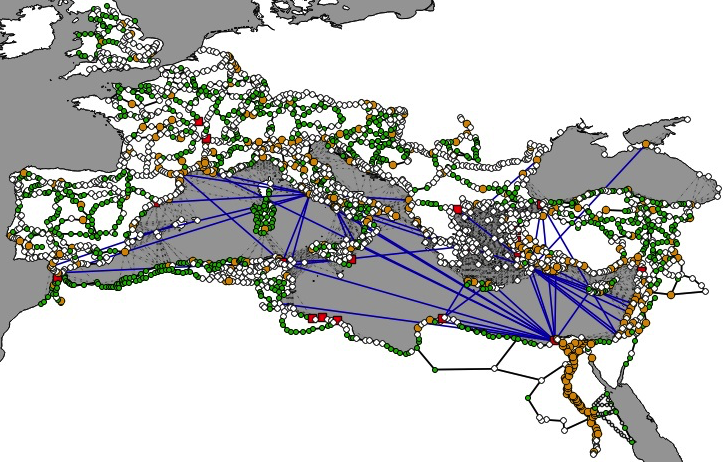

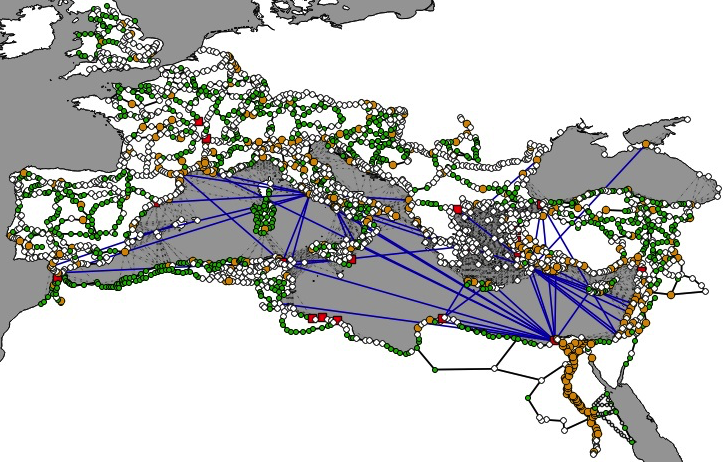

Spread of Antonine Plague (map from romeacrosseurope.com)

And there was such a pestilence, besides, that the dead were removed in carts and wagons. About this time, also, the two emperors ratified certain very stringent laws on burial and tombs, in which they even forbade any one to build a tomb at his country-place, a law still in force. Thousands were carried off by the pestilence, including many nobles, for the most prominent of whom [the emperor] erected statues. Such, too, was his kindliness of heart that he had funeral ceremonies performed for the lower classes even at the public expense…

(Historia Augusta, Life of Marcus Aurelius, Part I, 13)

The Antonine Plague brought devastation to Rome and the Empire at large. Cassius Dio wrote that it caused up to 2000 deaths a day in Rome itself. It has been estimated that there were approximately 5 million deaths from this pandemic, and that about one third of the Empire’s population was wiped out.

One theory for the widespread destruction wrought by the Antonine Plague is that this was the very first time small pox appeared in the Empire, and so, without any sort of prior immunity, the people were as lambs to the slaughter.

It also massacred the army in which it had started, spreading to Gaul and along the entire Rhine and Danube frontier. Rome’s defences were down, and the tribes to the north chose this moment to attack.

Marcus Aurelius’ war with the Germanic tribes – scene from the movie Gladiator

It is hard to imagine the terror spreading across the Empire during this terrible time in which Rome was beset by the Marcomanni and their allies in the north and the plague at its heart.

Eventually, the barbarians were defeated – and that alone is a wonder! – but the plague, even though it eventually stopped, left the Roman Empire scarred. Entire towns were wiped out and outposts were lost because the troops were too sick to fight.

It has also been hypothesized that the Roman embassies that Marcus Aurelius had sent to China’s Han emperor were perhaps responsible for the outbreak of plague that was recorded there.

There can be little doubt that the Antonine Plague was perhaps the most deadly crisis Rome had ever been faced with. The plague did not discriminate, striking at rich and poor, weak and strong alike. It seems likely that it was also responsible for the death of Emperor Lucius Verus, who died two years into the northern wars, and maybe even Rome’s great philosopher emperor, Marcus Aurelius, who passed in A.D. 180 just before the end of the pandemic.

Relief of Emperor Marcus Aurelius performing a sacrifice

He died in the following manner: When he began to grow ill, he summoned his son and besought him first of all not to think lightly of what remained of the war, lest he seem a traitor to the state. And when his son replied that his first desire was good health, he allowed him to do as he wished, only asking him to wait a few days and not leave at once. Then, being eager to die, he refrained from eating or drinking, and so aggravated the disease. On the sixth day he summoned his friends, and with derision for all human affairs and scorn for death, said to them: “Why do you weep for me, instead of thinking about the pestilence and about death which is the common lot of us all?” And when they were about to retire he groaned and said: “If you now grant me leave to go, I bid you farewell and pass on before.” And when he was asked to whom he commended his son he replied: “To you, if he prove worthy, and to the immortal gods”. The army, when they learned of his sickness, lamented loudly, for they loved him singularly. On the seventh day he was weary and admitted only his son, and even him he at once sent away in fear that he would catch the disease. And when his son had gone, he covered his head as though he wished to sleep and during the night he breathed his last. It is said that he foresaw that after his death Commodus would turn out as he actually did, and expressed the wish that his son might die, lest, as he himself said, he should become another Nero, Caligula, or Domitian.

(Historia Augusta, Life of Marcus Aurelius, Part II, 28)

I hope you’ve ‘enjoyed’, or at least learned something from this post on the Antonine Plague and disease in ancient Rome.

Stay tuned for the seventh and final part in The World of The Dragon: Genesis blog series in which we will look briefly at the sibling rivalry that beset the reign of one of Rome’s most infamous emperors – Commodus.

Thank you for reading.