Greetings ancient history lovers!

It’s been a while since the last Ancient Everyday blog post. If you missed the last one on Roman oil lamps, you can read it HERE.

Today we’re going to take a brief look at coinage in Ancient Rome from it’s inception to the early Imperial period and reforms of Emperor Augustus.

One of the reasons I love writing the Ancient Everyday series is that it shows is how much we actually have in common with the Roman world as far as our daily experiences.

A Roman coin hoard

Now, while we might not all have a big cache of loot lying buried in our back gardens, we do use money in some way shape or form on a daily basis.

Romans were no different in that regard, and whether they were getting paid for their legionary service, shopping in the markets of Trajan, or paying for the company of a lovely lupa in the streets of Pompeii, money was exchanged, and that usually in the form of coin.

But coins did not always exist in Rome, indeed not really across most of the early Mediterranean world.

The Mediterranean world of the Roman Empire

In the ancient world, coins were first produced in the Greek cities of Asia Minor in the late 7th century B.C. These first coins were made of something called ‘electrum’ which was a mixture of gold and silver with simple designs upon them.

Eventually, by about 500 B.C. coin production had spread across the Aegean and to the Greek colonies of southern Italy. These first coins were of pure silver, but the mints of these southern Italian Greeks also produced the first coins made of bronze.

However, before coins were common across Italy, the currency usually came in the form of irregular-shaped lumps of bronze known as aes rude. These were valued by weight.

aes rude – bronze ignots

By the 4th century B.C. bronze was being cast in regular-sized, cast bars, and then by the 3rd century B.C. standard weights were introduced and bars were stamped with images. These were known as aes signatum.

During the Republic, c. 289 B.C., aes grave were introduced. These were pieces of bronze about four inches in diameter that were cast in molds. They superseded the previous, larger bronze bars and became known as an as, or aes, the name given to one of the later denominations of Roman coin.

The as was then divided into smaller values such as a semis (half-as), a triens (a third), a quadrans (a quarter), a sextans (a sixth), and an uncia (a twelfth). These were quite small, but perhaps they would have got you a honeyed pastry in the forum!

Artist impression of a Roman street scene

As Rome grew in power and wealth, the coinage seemed to follow suit. In the early 3rd century B.C., Roman silver coins began to appear, and these were based on Greek designs coming out of southern Italy. It appears that the first silver coins were struck in Rome itself from about 269 B.C., and the first silver denarii were issued around 211 B.C.

Eventually, silver became the standard for coinage over the previous bronze, and the denarius became the main silver coin of the Roman world.

Other changes were afoot too…

The as was reduced in size so that 1 denarius was equal to 10 asses in the second century B.C. And, around the time of the Second Punic War, gold coins were first issued.

Gold aureus of Antoninus Pius

Around 24 B.C. the Emperor Augustus established a standard system of coinage, and under this system, the minting of gold and silver coins was a monopoly of the emperor, and bronze coinage was issued by the Senate of Rome.

Under this new system, four metals were used in coinage: gold, silver, brass, and bronze or copper.

Gold and silver coins were for official uses like salaries, and the baser coins were for everyday uses like market shopping or tipping the attendant at the baths. Augustus knew what he was doing as when a soldier was paid in silver or gold, then the emperor’s face was staring right back at him from that shiny surface. The troops knew who was paying them!

Over time, largely because of increased military spending, the silver denarius, the backbone of the Roman monetary system, became debased until, during the reign of Emperor Severus, a denarius contained only 40-50% silver and the rest was bronze.

But how much were the actual coins worth during the early Empire? Here are the approximate values of the various coins equal to one golden aureus:

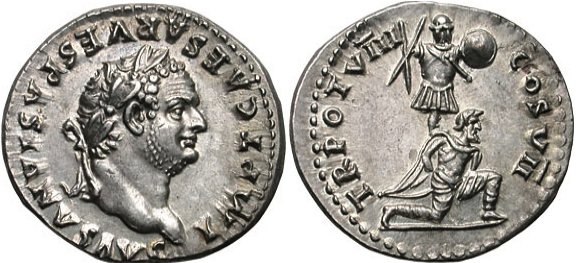

Silver denarius of the Emperor Titus commemorating ‘victory’ over the Jews

You needed 25 silver denarii to equal 1 aureus.

Sestertius of the Emperor Trajan

100 brass sestertii were equal to 1 aureus.

Dupondius of the Emperor Claudius

You needed 200 brass dupondii for one aureus.

Bronze as of the Emperor Nero (pun slightly intended!)

400 bronze asses equaled one golden aureus.

Brass semi as showing horses

800 brass semis were needed to equal 1 aureus.

Bronze quadrans of Emperor Hadrian

And a whopping 1600 bronze quadrans were needed to equal the value of one aureus!

I imagine that the purses of the rich were much easier to carry around than those of the poorer classes in ancient Rome. That’s a lot of bronze to equal just one gold coin!

Of course, in the later Empire, some new denominations came into effect, such as the argenteus, the follis, the solidus, and the centenionalis. Values fluctuated and metals were debased depending on which way the Roman economy veered. Not unlike today, I suppose.

There is one aspect that we should touch on too, and that is the powerful marketing tool coinage was for emperors. Coins were everywhere and in everyone’s hands, and what better way to let the people of the Empire know who was their master and protector than to put your face on the very coins they sought to collect and use to pay for things in their daily lives.

With coinage, the Emperor’s face was with you at all times, reminding you who was in charge. Coins gave you their likeness and also helped to commemorate victories over Rome’s enemies.

One thing is for sure…

In the world of Imperial Rome, for better or worse, money was one of the things that made the wheels of the Empire turn, and coin passed through the hands of rich and poor alike. Only some had more of it than others.

Thank you for reading.