The Art Beneath our Feet – Remote Mosaic in Roman North Africa

Greetings history-lovers!

Today we have a bit of a different post for you.

I don’t know about you, but whenever I travel around the Mediterranean to visit museums and archaeological sites, one of the things that always draws my eye are mosaics.

I can’t get enough of them to be honest. They fascinate me endlessly and I’m always shocked by how thousands of tiny tesserae can be combined to make almost lifelike images.

In a way, mosaics are artifacts that we often take for granted today as we tour ancient sites, but the fact remains that mosaic making is an ancient art form that has been used to decorate floors, walls, and ceilings for centuries.

The art of mosaic making reached its zenith during the Roman Empire, and Greek and Roman mosaicists across the empire produced some of the most beautiful and intricate mosaics in the world from Rome to North Africa and Carthage to Zeugma along the Euphrates river where some of the most glorious mosaics of the Roman world were rescued.

In this post, we will explore the art of mosaic making in the Roman Empire, and the techniques, materials, and designs that made it so unique.

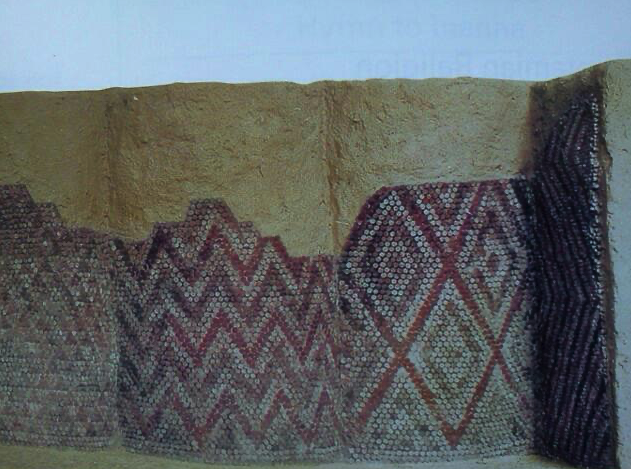

Mosaic wall in Mesopotamia – 3rd Millennium B.C.E. (source: Klink)

Mosaic making is an art form that dates back to ancient Mesopotamia, where it was used to decorate the floors and walls of temples and palaces in the third millennium B.C.E.

The art of mosaic making was also popular in ancient Greece, where it was used to decorate public buildings and homes. On the sacred island of Delos, the mythical birthplace of Apollo, some of the most beautiful mosaics of the ancient Greek world are still visible, open to the Delian sky. If you look around the edges of this very website, you’ll see one of them!

Mosaic at the House of the Dolphins on Delos.

However, it was during the Roman Empire that mosaic making reached the height of sophistication.

Roman mosaics were characterized by their intricate designs, complex patterns, and use of a wide variety of materials. They were used to decorate the floors, walls, and ceilings of public buildings, such as temples, palaces, and baths, as well as private homes.

The range and beauty of Roman mosaics, as well as the skills of Roman mosaicists, really hit me when I was visiting the Bardo Museum in Tunis (Carthage) some years ago when doing research for Children of Apollo. Room after room contained mosaics that seemed to move upon the very walls and floors. To read about my visit to the Bardo Museum just CLICK HERE.

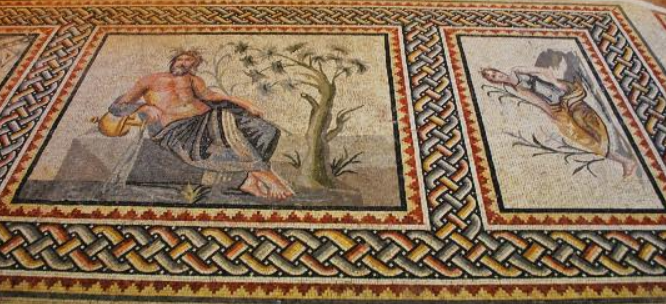

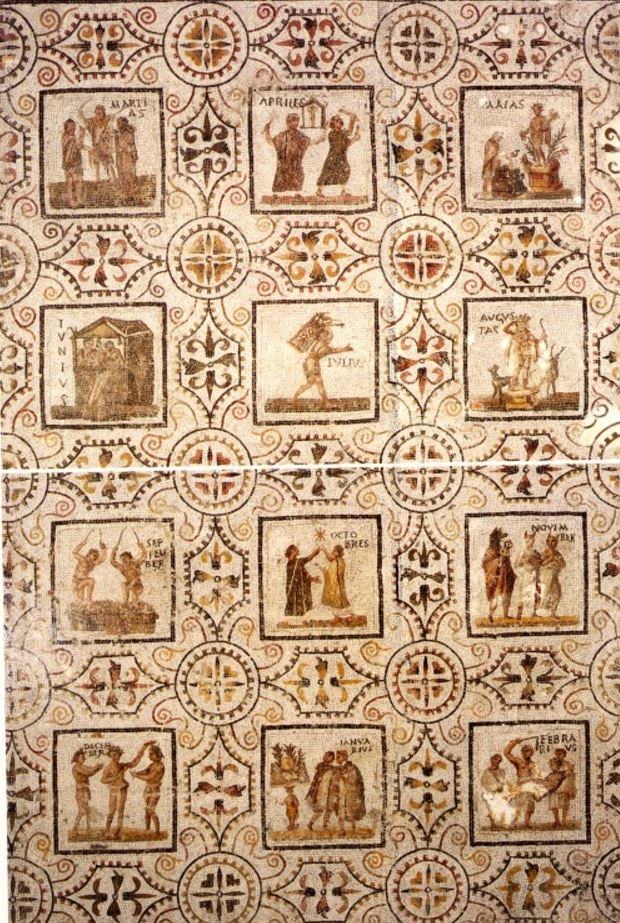

Roman mosaic representation of the months from North Africa

When it came to creating these intricate masterpieces, the techniques used by Roman mosaicists were highly sophisticated and involved a great deal of skill and precision.

Mosaics were created by laying small pieces of coloured stone, glass, or ceramic tiles, called tesserae, onto a bed of wet plaster. The tesserae were arranged to create intricate designs and patterns, and the finished mosaic was polished to create a smooth, even surface.

Roman mosaicists used a wide variety of materials to create their mosaics. The most commonly used materials were marble, limestone, and glass, which were all readily available in the Roman Empire. The tesserae were cut into small square or rectangular pieces, and were often arranged in intricate patterns and design.

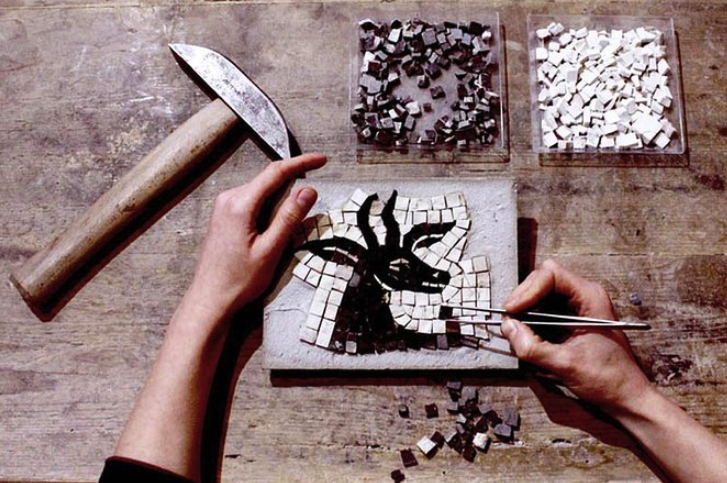

Some mosaicist tools and materials

Roman mosaics were famous for their intricate designs and patterns, which often depicted scenes from mythology, nature, and everyday life. We learn a lot about the latter from mosaics! The designs were created by arranging the tesserae in a specific pattern, and it is believed they may have used drawings as a guide.

Some of the most famous Roman mosaics are the ones that depict scenes from mythology, such as the four seasons or the twelve signs of the zodiac. These mosaics often featured elaborate designs and intricate patterns, and were highly prized by the wealthy and powerful.

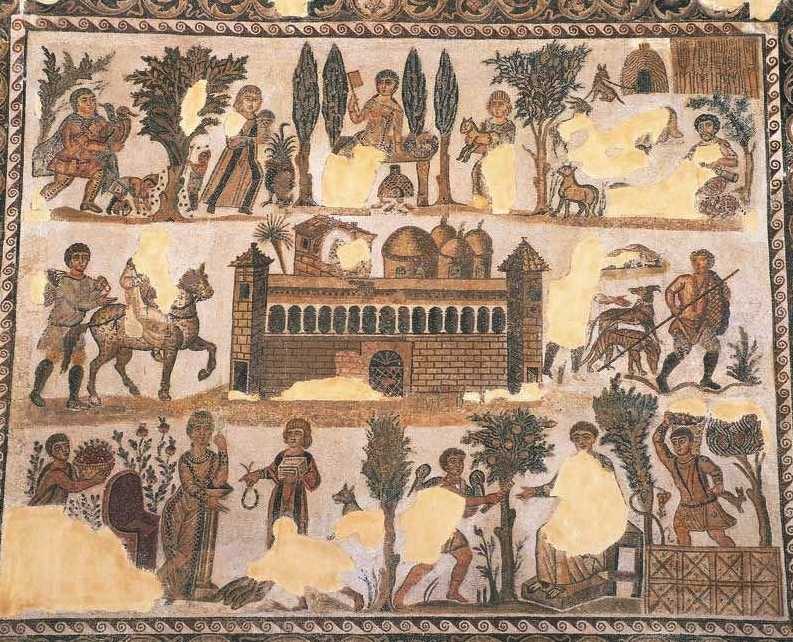

Mosaic depicting Roman country life and activities.

Roman mosaicists were highly skilled craftsmen who were revered for their artistry and technical skill. It is believed that they worked in workshops, where they would create mosaics for public and private buildings. Despite the survival of countless mosaics around the Mediterranean world, the actual names of these skilled mosaicists do not survive.

One of the few mosaicist’s names that have come down to us from the Roman world is the Greek artist Sosus of Pergamon, who created the famous “unswept floor” and “doves drinking at a bowl” mosaics.

Some mosaicists did sign their works, leaving behind their names for posterity. The famous mosaicist, Dioscurides of Samos, signed his name on a mosaic in Pompeii, ensuring his reputation would endure. However, the majority of mosaicists remain anonymous, as the focus was primarily on the artwork itself rather than the individual artist.

‘Doves drinking at a bowl’ mosaic by Sosus of Pergamon

Though we do not know many of their names, it is believed that mosaicists were highly respected in Roman society, and were often commissioned to create mosaics for the wealthy and powerful. They were also highly skilled in the use of colour and texture, and were able to create mosaics that were both beautiful and durable.

Roman mosaicists worked in specialized workshops where they would design and create their mosaics. These workshops were bustling centres of artistic activity, employing skilled artisans and apprentices who specialized in various aspects and stages of mosaic making from design to completion.

The mosaicists, often working in collaboration with architects and patrons, would create detailed sketches of the desired mosaic design. These sketches served as blueprints, guiding the placement of tesserae and ensuring the overall composition and proportions were accurate.

Mosaic of street performers by Dioscurides of Samos (Wikimedia Commons)

Once the design was finalized, the mosaicists would begin the painstaking process of selecting and cutting tesserae. They had to carefully choose stones, marbles, and glass pieces of various colours and textures to achieve the desired effect. The tesserae were then meticulously cut into uniform shapes, usually square or rectangular, using tools such as hammers and chisels.

To create a mosaic, the mosaicists would first prepare a flat surface by applying a layer of lime or gypsum plaster. This layer, known as the “bedding,” provided a stable base for the tesserae. Working in small sections, the mosaicists would apply a layer of wet mortar onto the bedding and carefully press the tesserae into it, one by one. They would often use special tools, such as tongs or tweezers, to ensure precise placement and alignment.

After the tesserae were set, the mosaicists would let the mortar dry and harden. Once the mosaic was solid, they would clean the surface and remove any excess mortar. The final step involved polishing the mosaic to achieve a smooth and lustrous finish. This was done by rubbing the surface with stones, sand, or even pieces of polished metal.

Preparing a mosaic bed

Roman mosaics displayed a wide range of themes and subjects, reflecting the cultural, mythological, and social context of the time. Mosaics were often used to depict scenes from mythology and history, showcasing the Romans’ deep appreciation for their ancestral stories and legendary heroes.

Mythological scenes featuring gods, goddesses, and mythical creatures were particularly popular. These mosaics brought ancient myths to life and adorned the walls and floors of temples, villas, and public spaces. The stories of the gods and heroes provided moral and religious lessons and connected the viewers with the divine.

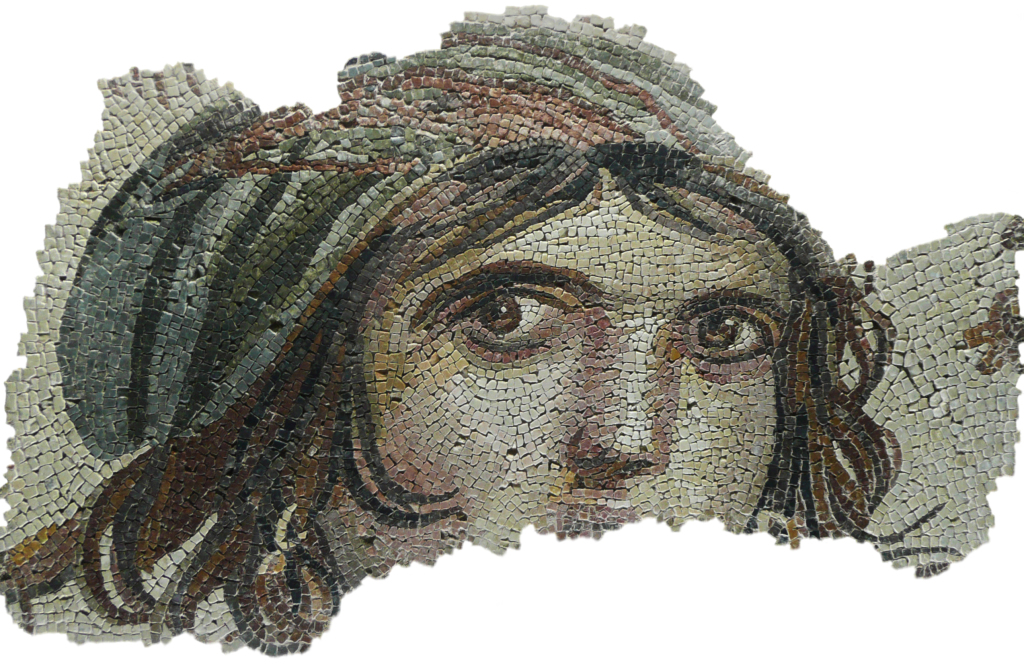

Mosaic depicting Odysseus in the Bardo Museum

In addition to mythology, Roman mosaics also depicted scenes from daily life, nature, and the world around them. Mosaics with intricate floral patterns, animals, landscapes, and still-life compositions were abundant. They celebrated the beauty of the natural world and brought elements of the outdoors into interior spaces.

The legacy of Roman mosaicists can be seen in the numerous surviving mosaics that have withstood the test of time. These mosaics, found in archaeological sites, museums, and private collections around the world, continue to captivate and inspire audiences with their beauty and craftsmanship.

The Lod Mosaic

While the Roman Empire may have come to an end, the art of mosaic making has not faded into history. It continues to thrive in the modern world, with artisans and enthusiasts carrying on the ancient tradition.

Today, mosaicists draw inspiration from the techniques and designs of their Roman predecessors while incorporating contemporary styles and materials. They explore new possibilities by combining traditional tesserae with elements such as glass beads, ceramic tiles, and even recycled materials. Modern technology has also enhanced the craft, allowing for precise cutting and shaping of tesserae and the creation of intricate designs with computer-aided programs.

Gaudi’s Trencadis Mosaics at Sagrada Familia (source: Sagrada Familia blog)

Mosaic making has found its place not only in the realm of traditional art but also in contemporary architecture and public installations. Mosaics grace the facades of buildings, embellish public spaces, and adorn urban landscapes, adding colour, vibrancy, and cultural richness to our surroundings.

There are even mosaic-making workshops and schools offer opportunities for aspiring artists to learn the ancient techniques and develop their skills. Courses and classes provide a platform for creativity and artistic expression, ensuring that the art of mosaic making will continue to evolve and flourish. CLICK HERE for some recommended Greek and Roman mosaic making classes you can take today! Who knows? Maybe your work will adorn the floor of your home or a public space!

The art of mosaic making reached its height of sophistication during the Roman Empire, and Greek and Roman mosaicists produced some of the most beautiful and intricate mosaics in the world, the legacy of which can still be felt to this day.

Their names may have been forgotten, but their artistic creations live on!

Thank you for reading.

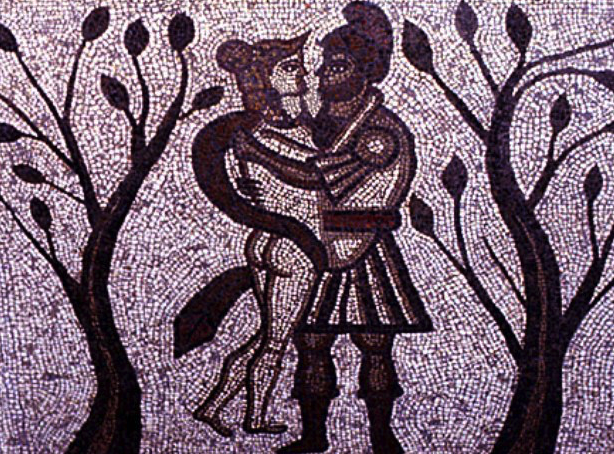

Aeneas and Dido mosaic from Low Ham Roman Villa near Ilchester