I think I’m feeling that deep-winter urge to travel again.

I’m thinking of warmer climes, of faraway lands, and the sanctuary that ancient places provide in contrast to the chaos of a big city.

Today, I’d like to take a brief look at a site that may be known to some of you, but which often falls off of the tourist radar – Ancient Nemea.

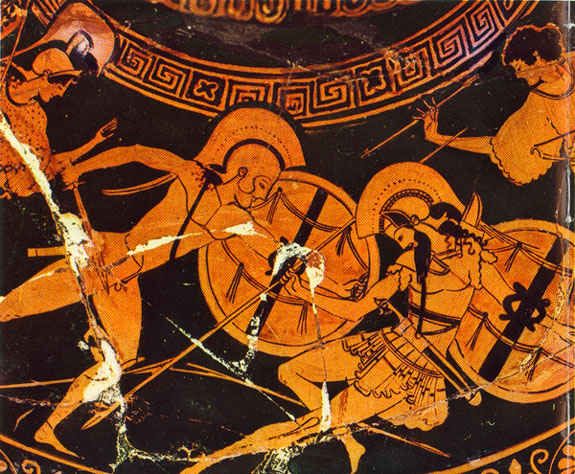

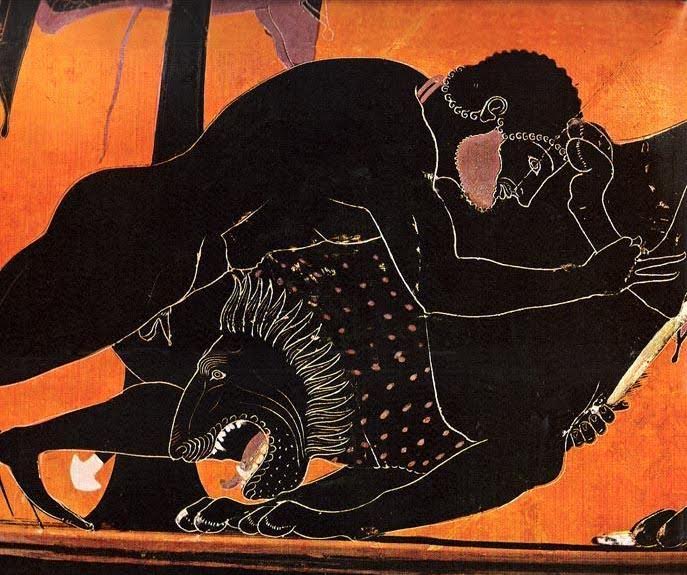

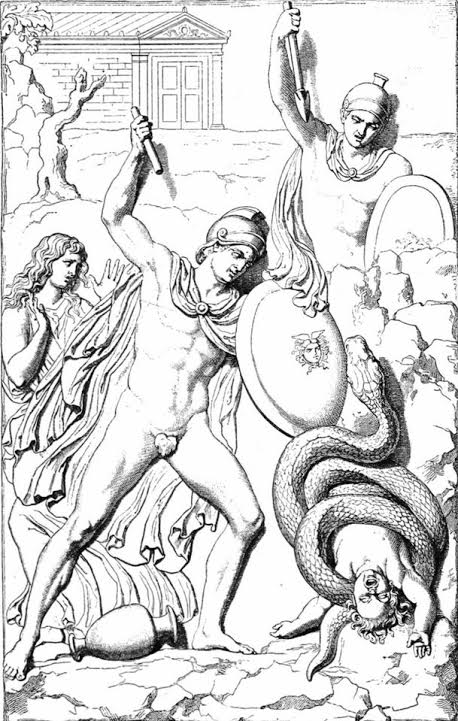

If you’ve heard of Nemea, it’s probably in relation to the first labour of Herakles in which the hero defeated the Nemean Lion.

Herakles and the Nemean Lion

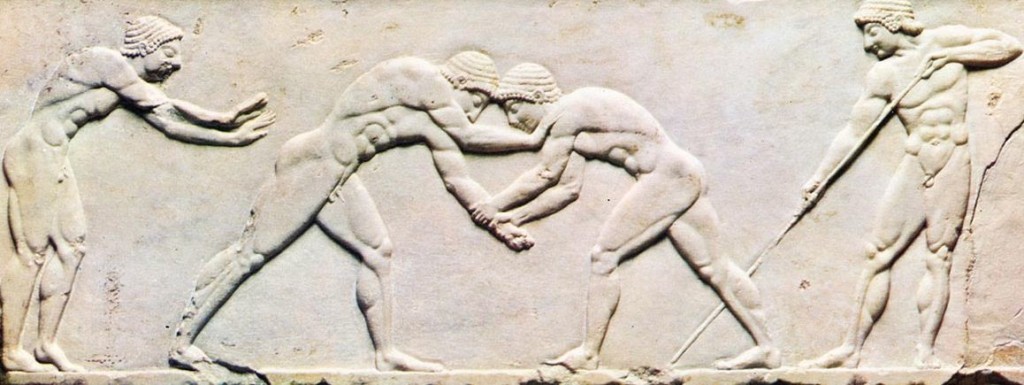

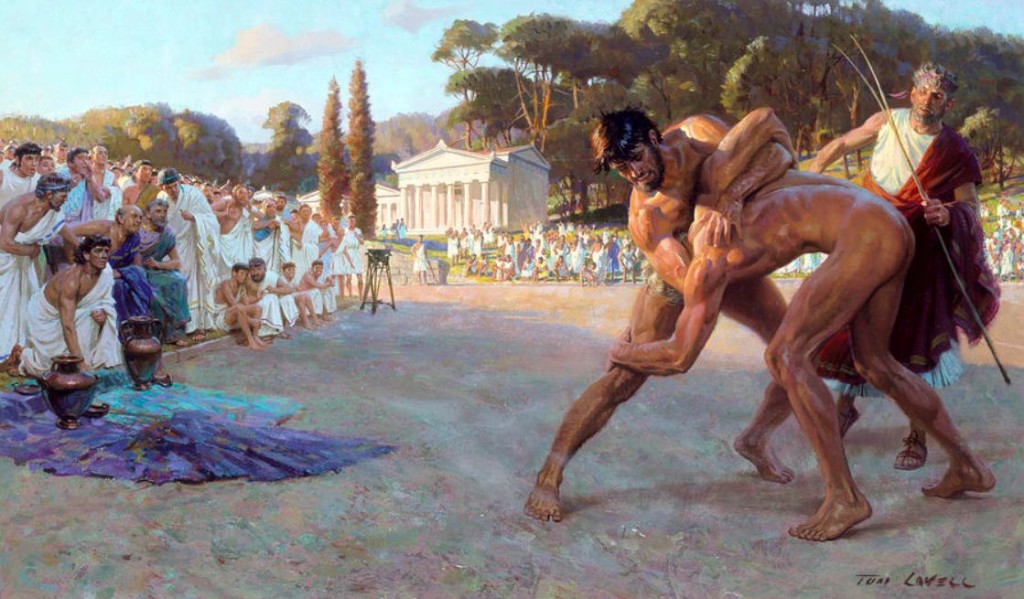

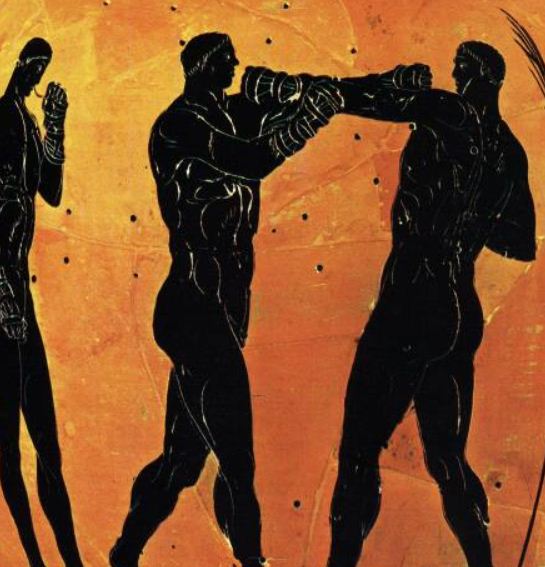

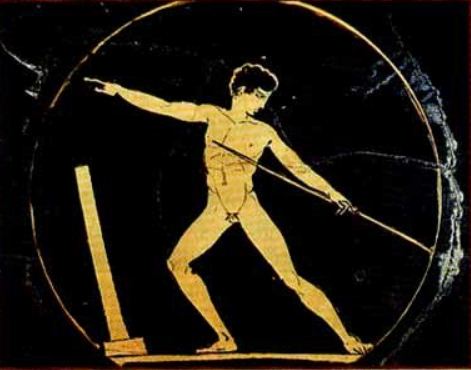

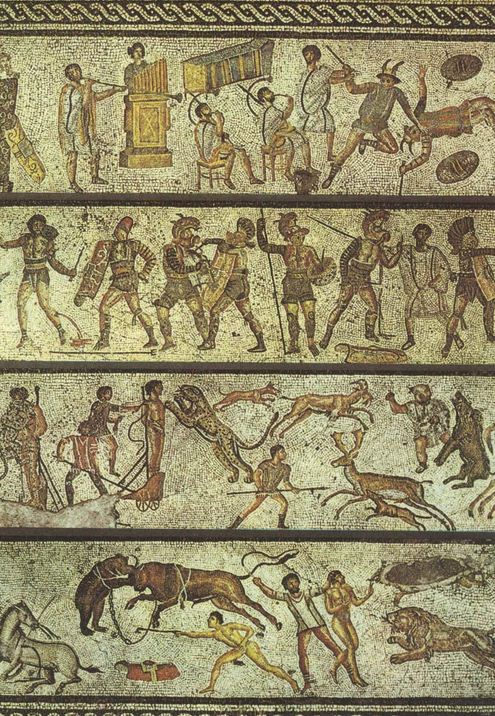

Nemea was, of course, also the site of one of the four ‘Crown Games’ of the ancient world, the other three being the Isthmian Games (at Isthmia, near Corinth), the Pythian Games (at Delphi), and the greatest of the four games, the Olympic Games (at Olympia).

But the Nemean Games were not started in honour of Herakles’ great labour.

In legend, the Nemean Games are related to the ‘Seven Against Thebes’, the group of warriors who went with Polynices to take back Thebes from his brother, Eteocles. On their way to Thebes, the Seven stopped in Nemea where King Lykourgos ruled with his queen, Eurydike.

The king and queen had a newborn son named Opheltes, whom they were told by the Oracle at Delphi that they could not let touch the ground until he could walk.

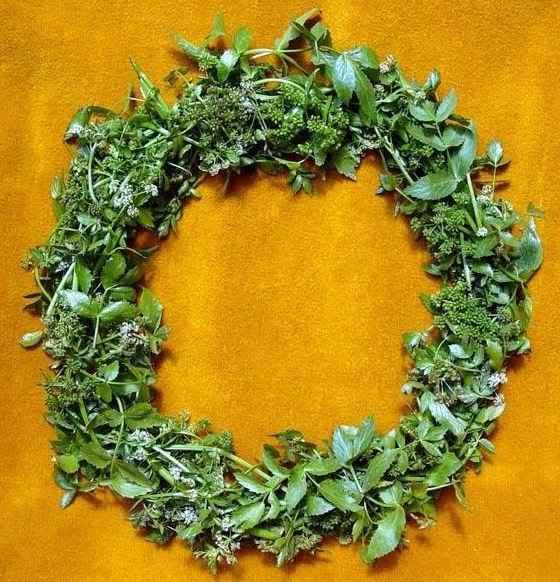

However, one day, the baby’s nurse, Hypsipyle, was walking with the baby when the Seven stopped in Nemea. The Seven asked where the nearest well was, and so Hypsipyle put the baby Opheltes on a bed of wild celery while she took the generals to the well.

The baby was set upon the ground in contradiction of the Oracle of Delphi’s warning, and so a snake came along and killed the baby Opheltes.

Opheltes being killed by the snake

The Seven saw this as a bad omen and sought to honour the soul of the slain child, and propitiate the Gods by holding funeral games on site.

Thus were the Nemean Games born.

Ancient Nemea is located in one of the most beautiful regions of the Peloponnese, a region pulsing with myth and legend. Tall mountains rise up above fertile plains filled with olive and orange groves, and miles and miles of grape vines.

The site itself is located to the north of Argos and Mycenae, and is much smaller than Delphi or Olympia, but no less interesting or beautiful.

View of the Temple of Zeus from the surrounding vineyards

The first historical games at Nemea were held in 573 B.C., and they took place every two years. There was no settlement at Nemea, and the games were most often under the auspices of Argos, moving to that ancient city to the south for long stretches of time, except during the period of Macedonian hegemony.

The sanctuary at Nemea was important in the ancient world, but somehow experienced more neglect than others when the Games were moved to Argos:

In Nemea there is a temple of Zeus Nemeios worth visiting, although the roof has collapsed and there is no longer any statue. Around the temple is a sacred cypress grove. Here was Opheltes, put on the grass by his wet-nurse, killed by the snake, according to the story. The inhabitants of Argos sacrifice to Zeus also in Nemea and choose a priest of Zeus Nemeios. They organize a running contest for men in armour at the festival of the Winter Nemea. So there is the grave of Opheltes, with a stone enclosure around it and inside the enclosure altars. There is also a tumulus as a monument for Lykourgos, the father of Opheltes. (Pausanias II 15, 2-3)

Pausanias, in his second century A.D. tour of Greece, describes the run-down ruins of the site during the Roman period.

Ancient Nemea from the air

I’ve only been to ancient Nemea once, but I still remember it quite well. The drive there was supremely pleasant, the cypress and plane-tree-lined roads winding among miles of vineyards that seemed somehow reminiscent of Tuscany’s Chiantigiana.

But this is Greece, and the difference is the sense of antiquity and legend that permeates the very air, the light, the landscape.

We pulled into the small parking lot, one of only a handful of cars, and entered through the small site-museum where we were met by a bust of none other than Julia Domna, the Roman empress of Septimius Severus, about whom I’ve written quite a bit.

Some people may say that the museum and the archaeological site are a bit of a let-down compared with Olympia, but I would say that this place is of utmost importance. A lot of archaeological work has been done here to improve our knowledge of Nemea’s importance and the importance of athletics in the ancient world.

There have been excavations on and off here since 1884, but the bulk of the work has been carried out by the University of California at Berkeley since 1974, and that important work is ongoing.

Temple of Zeus – before some of the columns were re-erected

There are two parts to the Nemea archaeological park – the Sanctuary of Zeus, and the Stadium.

We started in the sanctuary where one is drawn to the ruins of the temple of Zeus which was built c.330 B.C.

There is a wonderful, if small ruin that contains the remains of a sunken crypt accessed through the cella, or inner chamber. It is believed the crypt was either used as the site of an oracle, or as a treasury for the sanctuary.

On the east side of the temple is a feature that is unique to Nemea, and Isthmia (an altar to Poseidon), and that is a very long altar to Zeus where athletes and trainers swore their oaths and made sacrifices prior to the competitions. This altar dates to the fifth century B.C.

Model of the site, in the museum, showing the long altar in front of the temple of Zeus

The temple is surrounded by a square precinct that contained monuments, smaller altars, and a sacred grove of cypress trees.

It was a peaceful experience roaming this area of the sanctuary, the trees adding to the atmosphere. However, watch where you step! One of our party found a snake skin jutting from beneath one of the fallen column drums, and when he lifted it up, it had to be about five feet long.

Snakes! Why did it have to be snakes!

“Snakes! Why did it have to be snakes?”

Fortunately, the originator of that shed skin was nowhere to be seen.

With the cicadas whirring all around us, we looked over the scant remains of the other structures located on the site, including a bath house, a row of nine oikoi, club houses built by the various city states to shelter their attendant citizens at Nemea, and the large xenon, a hotel for dignitaries that is located on the south side of the sanctuary.

The sacred cypress grove in the sanctuary

The interesting thing about Nemea is that there was never a real settlement there during the Classical or Hellenistic periods. There were probably just a handful of people who lived there to tend the fields and care for the buildings the rest of the time.

During the Nemead, however, tens of thousands of Greeks gathered there for the games so that the valley of Nemea became a giant tent city, probably not unlike that which pops up at the Glastonbury festival.

Glastonbury Festival’s tent city

After visiting the main archaeological site, and then the roaming through the small site museum, we went back to our car to drive 400 meters down the road to the southeast where the stadium of Nemea is located.

During the Nemead, after the athletes had taken their oaths and made their offerings to Zeus in the sanctuary, they would have processed from the temple of Zeus to the stadium which was created by hollowing out a part of the nearby hill.

The stadium is definitely worth a visit and, as can be the case with many lesser known sites, it was virtually deserted when we arrived.

Nemea’s stadium is smaller than Olympia’s, but it’s still substantial, as it should have been for one of the four Crown Games.

It could seat up to 40,000 spectators in its day on the roughly hewn stone seats of the embankments.

The stadium of Nemea (Wikimedia Commons)

This place has some interesting features.

One of the most unique features is the ancient locker room which the processional way leads to from the sanctuary. It is here that the athletes would have stripped down, oiled themselves, and warmed up prior to competing.

The locker room of Nemea where athletes prepared for competition

Whereas at Olympia there were separate areas for doing these things, at Nemea, this locker room had multiple purposes.

Once the athletes were ready, they proceeded to enter the stadium through a vaulted tunnel that is still intact to this day, and graced with graffiti from some of the ancient athletes.

The tunnel leading from the locker room into the stadium

Visitors can walk through this tunnel and emerge into the bright sunlight of the stadium at roughly the half-way point.

It’s a wonderful feeling to step onto the stadium ground, and I was definitely reminiscent of my own track-and-field days, that familiar flutter of nerves and adrenaline rearing its long-dormant head.

It’s somewhat sobering to remember that the Nemean Games were begun, not as an entertaining athletic contest, but as a funerary event for a slain child.

When it’s not crowded, there is a perhaps a sense of gloom that lies over the place, despite the brilliant sunshine and colour of the landscape.

I walked around the edges of the stadium and looked at the other features of ancient ingenuity such as the stone channel that fed water around the edges of the stadium for athletes and spectators to drink, the water pumped in by way of pipes in the hill side.

Then there is the stone starting line across the track where you can see the bases for the starting mechanism and its thirteen gates.

The starting line in the stadium

As ever with these sites, it is good to pause and let your imagination fill in the gaps of what you are seeing.

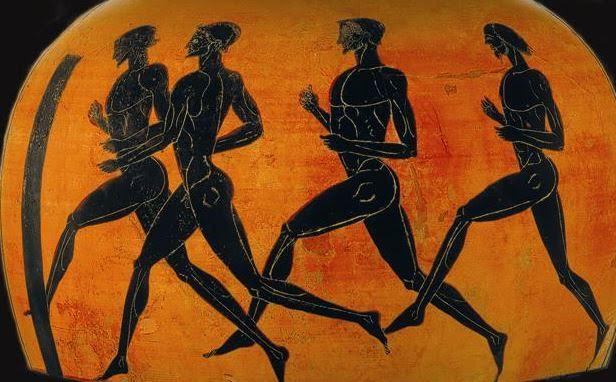

As I stood in the middle of the stadium floor, I imagined the embankments filled with people, a murmur running the length of the spectators, and then a hush and the judges, the Hellanodikai, in their black robes of mourning for the baby Opheltes, came out and sat themselves in their box toward the middle of the stadium.

I imagined that familiar hush as the runners lined up at the starting line, and then a few rapid heartbeats before the mechanism’s rope drops and the runners are off.

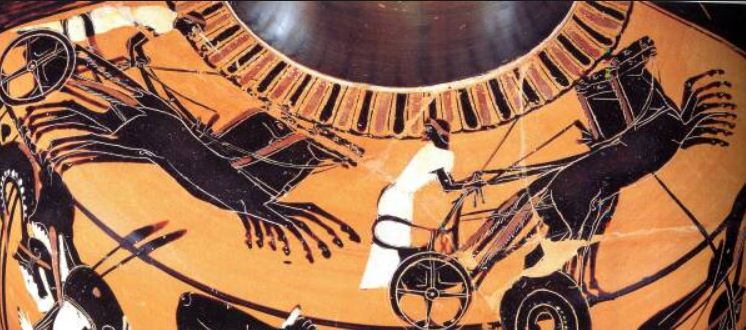

Ancient Runners

At Nemea, the victors were crowned not with olive (Olympia), bay (Delphi), or pine (Isthmia), but rather with a crown of the wild celery, that plant on which the child of Lykourgos and Eurydike had been placed before he was taken from them.

A crown of wild celery – the victory wreath of winners at the Nemean Games

When we finished looking at the site, and running a lap of our own, the sun was already beginning to dip behind the mountain peaks of Arkadia.

As we left the stadium behind, I felt like the place retained something of the cheers of crowds in ages past, but also the distant roar of a monstrous lion from the cave of its lair, said to be somewhere in the surrounding hills.

As I said, this land is pulsing with myth and legend, brought to life by its history and the hard work of the archaeologists who have sought to preserve and reconstruct the site, adding to our knowledge of it.

The temple of Zeus at Nemea after some of the columns were re-erected in 2013

But if you think that the Nemean Games are long dead, you might be mistaken.

Since around the year 2000, the games have experienced a revival, and they are being held again, this year, in June of 2016.

If you have ever wondered what it was like to compete in some of the rituals and competitions of ancient athletics, you can sign-up to do so at the revived Nemean Games. Watch this short video to find out more from the man who started it!

CLICK HERE to find out more about taking part in the modern games.

This looks like loads of fun, and a wonderful opportunity to participate in a unique living history event that brings students, academics, and anyone else interested in ancient history and athletics, together.

I’ve wanted to participate myself, but the timing has never coincided with my trips to Greece. I hope that someday, I can, thankful for the fact that the modern revival games do not involve running naked. They are also open to both men and woman, boys and girls.

There is one more thing I would suggest you do before leaving ancient Nemea in your traveller’s wake.

As you drive away, be sure to stop at one of the many roadside wine sellers and pick up a few bottles of the wonderful Nemean wine.

Countryside around Nemea