Salvete Romanophiles!

We’re back for a new Ancient Everyday post. If you missed the last one on coinage in the Roman world, you can check it out HERE.

This week, we’re looking at pets in the Roman world, and let me tell you, this turned out to be a much bigger, more complex topic than I had imagined! So, this will be something of an introduction to a topic that could well take up an entire book.

A quick shout-out to Jenny Villar who suggested this topic.

The first thing most of us picture when we think of animals in ancient Rome is no doubt the display bloody entertainment in amphitheatres like the Colosseum. But that is only part of the picture.

Before we discuss household pets, we should first take a look at the relationship ancient Romans actually had with animals.

Romans, it seems, were absolutely fascinated with animals!

They also had a strange, contradictory relationship with animals. They admired and were in awe of wildlife, and yet they used them to death, quite literally.

Animals served many purposes in the Roman world.

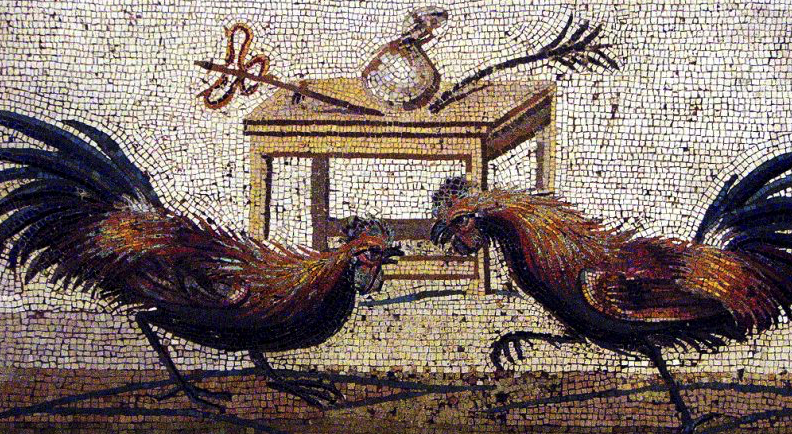

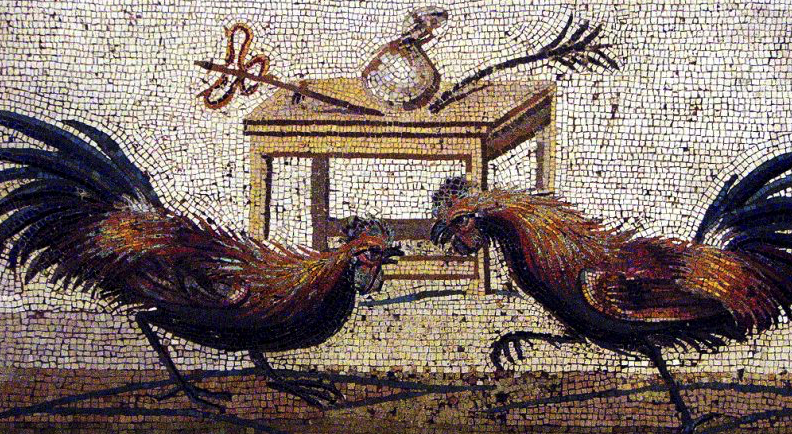

We have already alluded to entertainments in the amphitheatres and circuses of the Empire where any number of grisly pairings of beasts took place. But this category would also have included using animals for hunting (as both hunter and prey), in the wild or in the arena. Romans loved to watch animals be hunted, fight, and be killed, whether in the amphitheatre, or a private cock-fighting pit.

Animals were also labourers in the city, the countryside, and in the ranks of Rome’s legions across the Empire as beasts of burden and more.

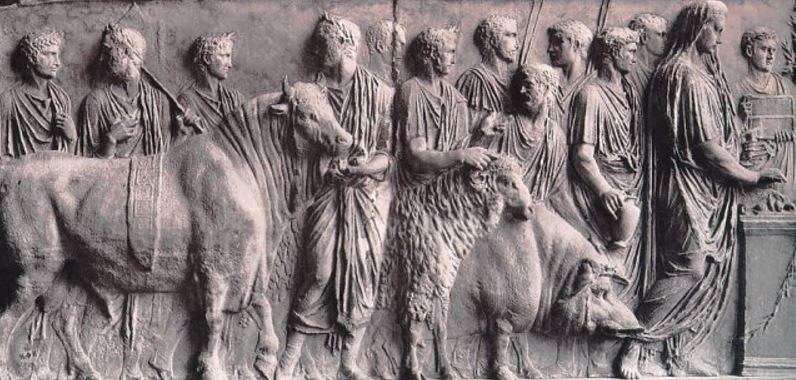

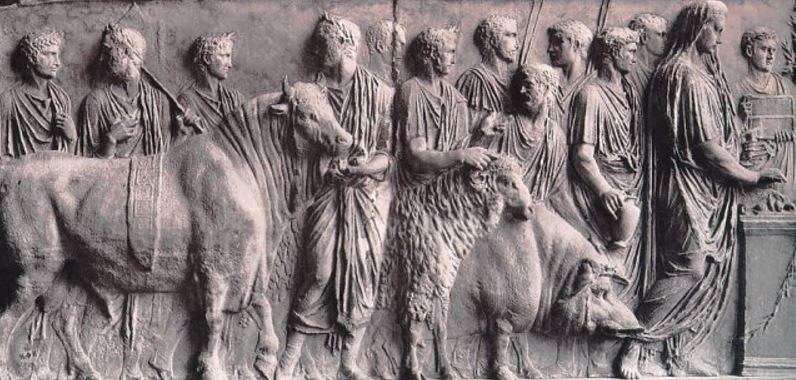

One area that is sometimes overlooked is the use of animals for religious purposes. Animals were sacrificed to the gods on a daily basis for a variety of reasons, and were often specifically bred for this purpose. As examples, only the whitest of doves might have been offered to Venus, Goddess of Love, or the blackest of sheep to chthonic gods such as Dis.

Relief of a Suovetaurilia ceremony

Animals were also used as ornaments in the Roman world, especially in the homes and villas of the rich and powerful. The emperors Domitian and Caracalla are both said to have had pet lions that followed them around, and some wealthy Romans even had elephants, the most exotic symbol of Roman power, to transport them to dinner parties.

What the valet slave would do with that, I don’t know!

What seems apparent is that exotic animals were as much a show of Roman wealth and power as the most expensive jewels, and some rich Romans had gardens filled with various exotic animals – a sort of ancient equivalent to a nineteenth-century menagerie.

Included in the long list of animals that appeared in the amphitheatres or homes of the Roman world were parrots, ostriches, monkeys, lions, leopards, lynxes, tigers, elephants, rhinos from Asia and Africa, and more.

Tombstone of a young girl with her dog

But we’re here to discuss animals as pets, specifically. In doing so, we might expect the usual array of animals we’re familiar with today, but, as ever, the Romans have put a twist on things for us. For instance, some children were said to have had pet goats or deer who were sometimes hooked up to little wagons or carts to pull them around.

We’ll go through a few of the animals that were said to have been kept as pets in ancient Rome.

Snakes. Let’s just get this one out of the way now. Yes. The Romans had pet snakes. In fact, the idea of a household with a resident snake is quite ancient.

In the ancient world, snakes were not only useful in destroying vermin such as mice and rats. They were also sacred, and strongly associated with healing. Think of the god Asclepius who is often pictured with a snake around a staff, that symbol which has been adopted by the medical profession.

In ancient Greece, many households had a snake which acted as a sort of household guardian. In fact, in certain parts of the Mediterranean to this day, it is considered bad luck to kill a snake.

In ancient Rome, emperors had sent to Epidaurus and the Sanctuary of Asclepius there for some of the sacred snakes used in healing, and these were kept on Tiber Island. The emperors Tiberius, Nero, and Elagabalus all kept snakes.

Now, whether or not the residents of Suburan tenement blocks kept snakes, I’m not sure. One hears of people with pet snakes today, so I imagine the idea is not so far-fetched.

Fish were also kept as pets, but these appear to have been something relegated to the upper classes who had the space and land for large fish ponds. One wonders how attached some became to these fish, for surely they would have ended up on the tricliniumtable at some point.

Sparrow! my pet’s delicious joy,

Wherewith in bosom nurst to toy

She loves, and gives her finger-tip

For sharp-nib’d greeding neb to nip,

Were she who my desire withstood

To seek some pet of merry mood,

As crumb o’ comfort for her grief,

Methinks her burning lowe’s relief:

Could I, as plays she, play with thee,

That mind might win from misery free!

…

To me t’were grateful (as they say),

Gold codling was to fleet-foot May,

Whose long-bound zone it loosed for aye.

(Catullus, Lesbia’s Sparrow)

Birds appear to have been much more popular a pet in ancient Rome than they are today. In the quote above, we hear from Catullus about Lesbia’s sparrow, or ‘passer’, which she adores.

When it comes to birds, with the length and breadth of the Empire, there was opportunity for an impressive array of species from ducks and geese to ostriches, peacocks, budgies and parrots. In the case of the latter, things get a bit odd when one considers the fact that parrot tongues were something of a delicacy. Again, the contradictory relationship Romans had with their animals.

One popular pastime was, of course, cock fighting. This still goes on in certain parts of the world today, but in ancient Rome, it was also a sport for the upper classes. Plutarch describes how Octavianus always beat Mark Antony at cock fighting:

…we are told that whenever, by way of diversion, lots were cast or dice thrown to decide matters in which they were engaged, Antony came off worsted. They would often match cocks, and often fighting quails, and Caesar’s would always be victorious. (Plutarch, Life of Antony)

I suppose Octavian had to be better at something than Mark Antony, and I imagine that it rankled Marcus Antonius to have Octavianus’ cock beat his own.

Anyway…moving on…

Cock fighting was a popular pastime.

Now we come to the felines of the Empire.

Certainly, exotic big cats were prized in the arenas and menageries, and we have already mentioned Domitian and Caracalla’s pet lions.

But let’s talk about cats as we know them. Today, cats are a very popular pet, but in the world of ancient Rome, they were not so adored as you might expect. Birds and dogs were more popular than cats, though if you walk the streets of Rome or Athens today, you’d think cats had taken over the world.

In ancient Rome, cats served a more utilitarian purpose. They were kept as pets, but it was more for the purpose of catching vermin. There were plenty of mice and rats to go around in Rome, of that we can be sure, though there is mention of another use. The ancient writer Palladius points out that the cattus (Palladius was apparently the first to use the word ‘cattus’) was very good for catching moles in artichoke beds!

I didn’t even know moles liked artichokes.

There was of course one part of the Empire where cats were revered above all other animals, and that was Egypt. Cats were sacred there, and in my research I even read that when cats were smuggled out of Egypt, a ransom was paid to get them back! I wonder if some entrepreneurial Romans ever created a cat-ransom racket to take advantage of the Egyptians’ love of felines?

Of course we cannot discuss animals in the Roman Empire without touching on what was considered a most noble animal – the horse.

Horses were extremely important in the ancient world. Not only were they used as beasts of burden and farm animals, but they were also essential on military campaign as pack animals or in the ranks as auxiliary cavalry.

They were also central to entertainment in the Roman world as chariot racing in the hippodromes of the Empire, like the Circus Maximus in Rome, was the most popular sport around. You can read more about chariot racing HERE. Champion horses were well-treated and even received a pension and luxurious retirement at the end of their careers.

Mosaic of a victorious chariot team

Horses were pets too, and one of the main activities for those in the countryside, rich and poor, was riding for leisure.

Probably one of the most famous instances of a pet horse from the Roman world is Caligula’s horse Incitatus. Suetonius goes into some detail:

He used to send his soldiers on the day before the games and order silence in the neighbourhood, to prevent the horse Incitatusfrom being disturbed. Besides a stall of marble, a manger of ivory, purple blankets and a collar of precious stones, he even gave this horse a house, a troop of slaves and furniture, for the more elegant entertainment of the guests invited in his name; and it is also said that he planned to make him consul. (Suetonius, Life of Caligula)

Statue thought to be a representation of Caligula and his favourite horse, Incitatus

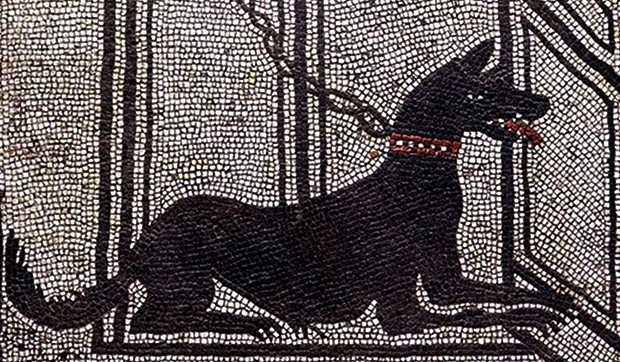

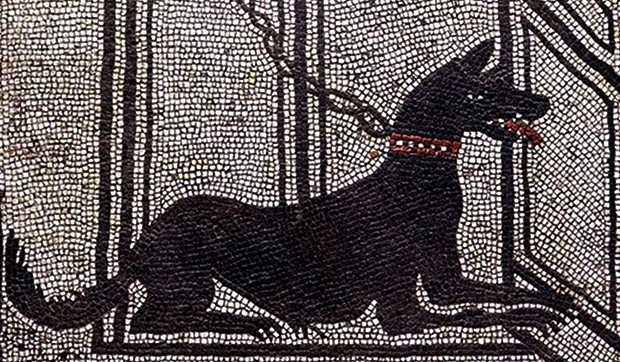

We’ve looked at a few species of animal that were popular among ancient Romans as pets, but none of those mentioned above were more popular as pets in the ancient world than dogs.

As far as pets, dogs were the favourite, and they had an age-old relationship with humans. They were friends, workers, and family members. Dogs were even worthy of serving the gods – think of Diana and her hunting hounds.

The Goddess Diana and one of her hounds

The oldest mention of a dog by name is in the Odyssey when there is reference to Odysseus’ dog, Argus.

‘This dog,’ answered Eumaios, ‘belonged to him who has died in a far country. If he were what he was when Odysseus left for Troy, he would soon show you what he could do. There was not a wild beast in the forest that could get away from him when he was once on its tracks. But now he has fallen on evil times, for his master is dead and gone, and the women take no care of him. Servants never do their work when their master’s hand is no longer over them, for Zeus takes half the goodness out of a man when he makes a slave of him.’

So saying he entered the well-built mansion, and made straight for the riotous pretenders in the hall. But Argos passed into the darkness of death, now that he had fulfilled his destiny of faith and seen his master once more after twenty years. (Homer, The Odyssey, Book 17)

There were different breeds for different purposes in ancient Rome. There were dogs for entertainment, fighting in the arena. These dogs were known as canes pugnaces. There were dogs in the Roman army, usually a breed of mastiff, and also for use as guard dogs.

A modern Maltese – the closest breed to the Roman lap dog

The Roman agriculture writer, Grattius, goes into some detail about various breeds of dogs:

Dogs belong to a thousand lands and they each have characteristics derived from their origin. The Median dog, though undisciplined, is a great fighter, and great glory exalts the far-distant Celtic dogs. Those of the Geloni, on the other hand, shirk a combat and dislike fighting, but they have wise instincts: the Persian is quick in both respects. Some rear Chinese dogs, a breed of unmanageable ferocity; but the Lycaonians, on the other hand, are easy-tempered and big in limb. The Hyrcanian dog, however, is not content with all the energy belonging to his stock: the females of their own will seek unions with wild beasts in the woods: Venus grants them meetings and joins them in the alliance of love. Then the savage paramour wanders safely amid the pens of tame cattle, and the bitch, freely daring to approach the formidable tiger, produces offspring of nobler blood. The whelp, however, has headlong courage: you will find him a‑hunting in the very yard and growing at the expense of much of the cattle’s blood. Still you should rear him: whatever enormities he has placed to his charge at home, he will obliterate them as a mighty combatant on gaining the forest. But that same Umbrian dog which has tracked wild beasts flees from facing them. Would that with his fidelity and shrewdness in scent he could have corresponding courage and corresponding will-power in the conflict! What if you visit the straits of the Morini, tide-swept by a wayward sea, and choose to penetrate even among the Britons? O how great your reward, how great your gain beyond any outlays! If you are not bent on looks and deceptive graces (this is the one defect of the British whelps), at any rate when serious work has come, when bravery must be shown, and the impetuous War-god calls in the utmost hazard, then you could not admire the renowned Molossians so much. (Grattius, Cynegeticon)

Wolfhounds and greyhounds were used for hunting by Romans, and there were even dogs used for religious sacrifice.

Apart from the larger breeds used for the purposes mentioned above, smaller lapdogs were very popular house pets in the Roman world. These were most likely similar to today’s maltese breed of dog.

There are several examples of beloved dogs on grave monuments for family or children that survive. The fact that Romans even did this is testament to the importance placed upon them.

A terracotta rattle in the shape of a dog

We have but scratched the surface of this vast topic on pets and animals in the Roman world. I hope you’ve found it interesting.

At the end of the day, the wide array of animals that served as pets, workers, food, religious sacrifice and more was as vast and varied a reflection of the world as the Roman Empire itself.

Thank you for reading.