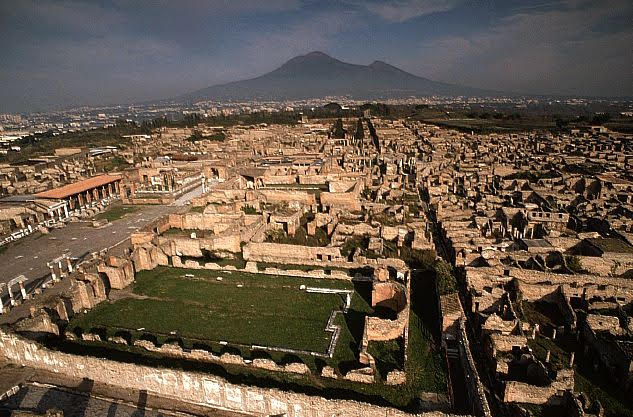

Pompeii

Pompeii – A Brief Introduction with Archaeologist, Raven Todd DaSilva

Hello again, ancient history-lovers!

Way back in the dark days of February, archaeologist Raven Todd DaSilva came to speak to us about gladiators and the famous thumbs-up gesture that we associate with that ancient blood sport. If you missed that, you can check it out HERE.

I’m thrilled to say that Raven is back on the blog with us this week for a brief introduction to one of the great disasters of the Roman world: the destruction of Pompeii.

Raven visited the archaeological site of Pompeii recently and is here to share a bit of the history with us, as well as some new theories around dating, as well as one of her brilliant videos!

So, ready as ever to get digging and get dirty, here’s Raven Todd DaSilva…

Pompeii, a Brief Introduction

By: Raven Todd DaSilva

On an unassuming day in 79 CE, the long-dormant Mount Vesuvius erupted. For three days, volcanic ash and rock rained down on the surrounding area, completely devastating the settlements around it. Most famously- the city of Pompeii.

Founded in the 6th century BCE along the Sarno river, Pompeii originated as a local settlement in Campania. The rich volcanic soil made it favourable for agricultural activity. In the 5th century BCE, the Samnites entered the area, while the 4th century BCE saw the beginning of Roman influence on the region. Pompeii began to flourish under this regime with massive building projects. It became a major port on the Bay of Naples, leading to its “golden age” in the 2nd century BCE. Pompeii was later turned into a seaside resort in 81 BCE. An earthquake damaged many of the buildings in 62 CE, which led to significant economic decline. By the time of the eruption, many of the grand villas built in the 2nd century BCE were converted for public use, leaving the city frozen in time during a period when its glory days were behind it.

Of course, Pompeii gets its fame from the devastating catastrophe because of the rare view it gives us regarding daily life at that time. As the eruption took the city’s inhabitants by surprise, they were not able to properly pack up and evacuate the area, leaving archaeologists with invaluable evidence as to how people really lived in the first century CE.

Not only are we fortunate enough to have the physical site of Pompeii, we also have a primary document describing the eruption of Vesuvius and the immediate aftermath. Pliny the Younger described the events that happened to his uncle, Pliny the Elder, who died assisting refugees onto the warships he was overseeing. This account is also where the infamous quote “Fortune favours the brave” originated. We also have Pliny’s own personal account from Misenum (about 30km away).

The eruption has been described by Pliny the Younger as:

…a pine tree, for it shot up to a great height in the form of a very tall trunk, which spread itself out at the top into a sort of branches; occasioned, I imagine, either by a sudden gust of air that impelled it, the force of which decreased as it advanced upwards, or the cloud itself being pressed back again by its own weight, expanded in the manner I have mentioned; it appeared sometimes bright and sometimes dark and spotted, according as it was either more or less impregnated with earth and cinders.(Letter LXV – To Cornelius Tacitus)

Once the danger of this eruption was realised, people began to evacuate hurriedly, with many people successfully fleeing. Pliny described those escaping as having “pillows tied upon their heads with napkins; and this was their whole defence against the storm of stones that fell around them” (Letter LXV). The stones thrust from the volcano were deadly, crashing through roofs, collapsing buildings and crushing those trying to take refuge under stairs and in cellars. Others, like Pliny the Elder, choked to death on the air as it filled with ash and noxious sulfurous gas. It is believed that 30,000 people died from the eruption.

The traditional date of the eruption is August 24th, as reported by Pliny the Younger, but it has come under scrutiny as further scientific evidence has come to light. Even as early as 1797, the archaeologist Carlo Maria Rosini questioned the date. Rosini reasoned that, as fruits found preserved at the site, such as chestnuts, pomegranates, figs, raisins and pinecones, become ripe in the fall months, they would not have been ripe so early in August. Another study of the distribution of the wind-blown ash at Pompeii supports this theory further. Probably one of the most telling artefacts is a silver coin found that was struck after September 8th, AD 79. As we don’t have an original copy of Pliny’s manuscript, we can assume a typo had been made along the way.

After compiling all this new data, a new eruption date of October 24th, 79 AD has been suggested.

After the eruption, the city remained largely undisturbed until 1738 when Charles of Bourbon, the King of Naples dispatched a team of labourers to hunt for treasures to give to his queen, Maria Amalia Christine, who was enamoured by previously excavated Roman sculptures in the area of Mount Vesuvius. The city of Herculaneum was found first, with Pompeii excavations following it about ten years later.

Today, Pompeii is one of the most popular and well-known archaeological sites, with the longest continual excavation period in the world. With respect to the study of daily life of Rome, it is undeniably important due to the sheer amount of data available. Each year, thousands of visitors flock to Pompeii to walk along the large stone slabs of its roads, visit its iconic brothels, and marvel at the mosaics, wall paintings and body casts preserved by the volcanic ash.

Raven Todd DaSilva is working on her Master’s in art conservation at the University of Amsterdam. Having studied archaeology and ancient history, she started Dig It With Raven to make archaeology, history and conservation exciting and freely accessible to everyone. You can follow all her adventures on Facebook and Instagram @digitwithraven

Resources

Online Articles:

Kris Hirst, What 250 Years of Excavation Have Taught Us About Pompeii https://www.thoughtco.com/pompeii-archaeology-famous-roman-tragedy-167411

Mark Cartwright, Pompeii https://www.ancient.eu/pompeii/

Joshua Hammer, The Fall and Rise and Fall of Pompeii https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/fall-rise-fall-pompeii-180955732/

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Pompeii: Portents of Disaster http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/romans/pompeii_portents_01.shtml

James Owens, Pompeii https://www.nationalgeographic.com/archaeology-and-history/archaeology/pompeii/

Wilhelmina Feemster Jashemski, Pompeii https://www.britannica.com/place/Pompeii

The Two Letters Written by Pliny the Younger about the Eruption of Vesuvius in 70 A.D. – http://www.pompeii.org.uk/s.php/tour-the-two-letters-written-by-pliny-the-elder-about-the-eruption-of-vesuvius-in-79-a-d-history-of-pompeii-en-238-s.htm

Books:

Beard, Mary (2008). Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town. Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-86197-596-6

Butterworth, Alex; Laurence, Ray (2005). Pompeii: The Living City. St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-0-312-35585-2

Kraus, Theodor (1975). Pompeii and Herculaneum: The Living Cities of the Dead. H. N. Abrams. ISBN 9780810904187

As ever, I’d like to thank Raven for another fascinating post and video.

Pompeii is one of those topics that I never tire of, and the exciting thing is that more is being revealed all the time. It’s also one site that I have not yet had the chance to visit, so I really enjoyed learning a bit more.

And I’m definitely looking forward to that next collaboration and video, Raven!

If you haven’t already done so, be sure to check the Dig It with Raven website and subscribe to Raven’s YouTube channel so you can stay up-to-date on all the latest videos about archaeology, history and art conservation.

Cheers, and before you leave, here’s a fantastic time lapse video of Raven’s visit to Pompeii!

The World of Killing the Hydra – Part II – Prostitution in the Roman Empire

We’re going to a different sort of place in this instalment of The World of Killing the Hydra.

In Part I, we explored the beauty of Leptis Magna which is where the book begins, and which was also the home of Emperor Septimius Severus.

But the Roman Empire was not all about beautiful monuments, lavish banquets, and the adoration of the people for the ruler of the time.

In fact, the Roman Empire had its own maze of back streets and alleyways where life was seedier, and more visceral. It wasn’t all polished marble, but rather slick brick and stinking cells.

WARNING: This post is not suitable for readers under 18 years of age. Also, if you are easily offended, some of the pictures of Pompeian frescoes in this post might be a bit too saucy for you. Just a word of warning for the innocent-minded.

We’re going to take a very brief look today at prostitutes and brothels in the Roman Empire.

Now, if you’re suddenly hoping that Killing the Hydra is my attempt at historical erotica, well, you’re looking in the wrong place. The book is not an orgy extravaganza. If you want that, check out the film Caligula with Malcolm McDowell in the title role.

However, you can’t really write about the Roman world without touching on the long-standing role that prostitution and brothels had to play in society.

They existed, and they most certainly flourished. People of all classes, mostly men, made it a normal practice to visit their favourite brothel from time to time.

If you liked the HBO show ROME, you might have an image of Titus Pullo whoring his way through the Subura with his jug of wine in hand. Certainly, this sort of behaviour was not uncommon, especially for troops fresh back from the wars and looking for a good time.

The flip side might be the richer, upper class nobility who may have believed visiting prostitutes was fine, as long as it was done in moderation and didn’t cause a scandal.

The prostitution scene in the Empire was as large and varied as the workers and clients who kept it running. There was something for everyone!

But let’s look at things a bit more closely.

The She-Wolf, or ‘lupa’, suckling Romulus and Remus

One could say that prostitution has ties to the founding of Rome itself.

You may have read about Romulus and Remus, the brothers who founded Rome and were suckled by the She Wolf, or Lupa.

We have heard of lost children being raised by wolves before, but in the instance of Romulus and Remus, many believe that they were actually raised by a prostitute who found them on the banks of the Tiber. The slang word for prostitute in Latin was lupa.

And the word for brothel was in fact lupanar or lupanarium.

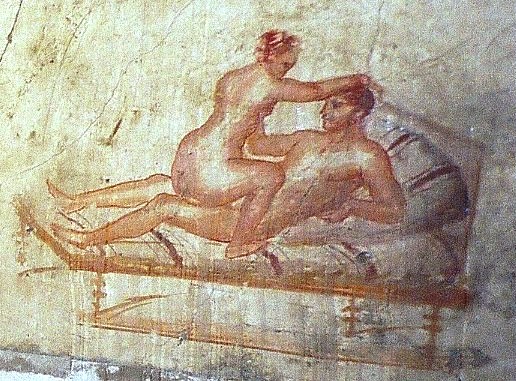

Clients were drawn in by the sexual allure of displayed ‘wares’, sometimes lined up naked on the curbside, and the various experiences to be had within. The latter were sometimes illustrated in frescoes or mosaics on the walls of the lupanar. These were intended to add to the atmosphere, or were a sort of menu of pleasures to be had.

There were of course ‘high-class’ prostitutes who catered to wealthy and powerful patrons, women who were skilled at conversation, music and poetry. These high end lupae provided an escape, or a feast with friends, in lavish surroundings coupled with a sort of blissful oblivion. Some might have been purchased by their wealthy clients to keep for themselves, and if that was the case they might have ‘enjoyed’ a relatively easy life compared to the alternative.

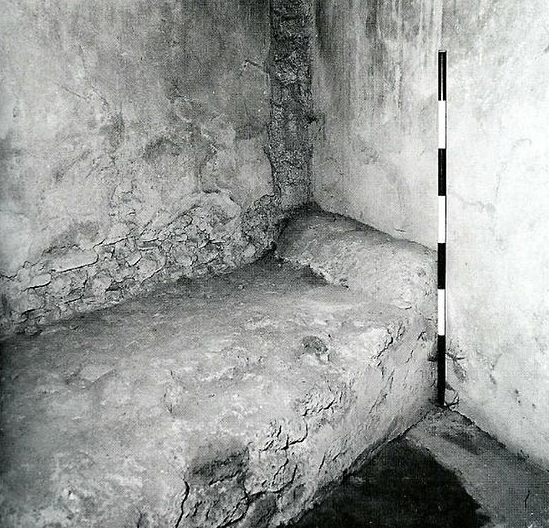

A lupa’s ‘office’ – a cement bed

The truth for most, however, was that they were slaves. And slaves in ancient Rome, as we all know, were objects, property to be used and disposed of on a whim.

Prostitutes – women, men, boys, girls, eunuchs etc. – were at the bottom of the social scale, along with actors and gladiators. They could be adored by clients one moment, and shunned the next. And if a lupa was no longer profitable, the leno (pimp), or the lena (madam) might sell them off as a liability, sending them to a life that was possibly even worse.

In ancient Rome, prostitution was legal and licensed, and it was normal for men of any social rank to enjoy the range of pleasures that were on offer. Every budget and taste was catered to, and because of Rome’s conquests, and the length and breadth of the Roman Empire in the early 3rd century, there would have been slaves of every nationality and colour. Clients of the lupanar would have had their choice of Egyptians, Parthians and Numidians, Germans, Britons, slaves from the far East and anywhere else, including Italians.

However, even though prostitution was regulated, don’t kid yourselves. This was not a question of morality, or curbing venereal diseases. This was about maximizing profit – prostitution was also taxed!

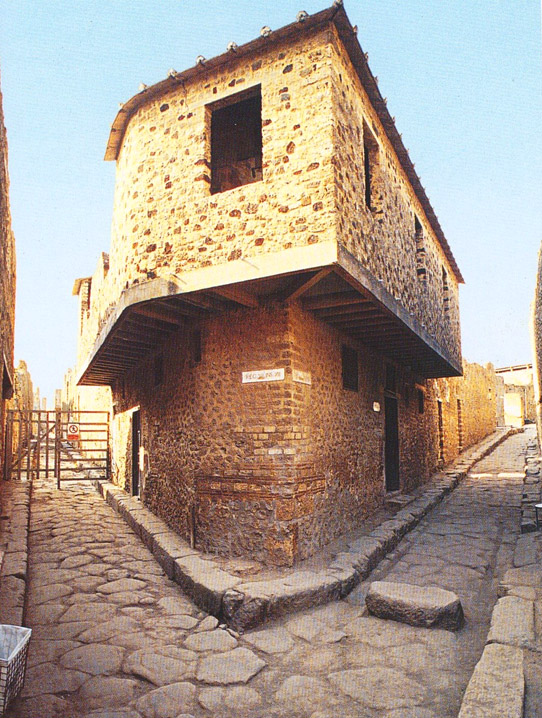

In Pompeii, prostitution became a sort of tourist trade. On the street pavement you just had to follow the phalluses to find the nearest brothel! There were something like thirty-five brothels in the town, and that’s not counting the small curbside cells or niches where the cheapest lupae provided quickies to passers-by.

The Great Lupanar of Pompeii

The biggest brothel in Pompeii however, was the ‘Great Lupanar’ located at a crossroads two blocks from the Forum. Many of the frescoes pictured here are from that building which had ten rooms, where most lupanars had just a few.

But we’ve only been looking at prostitution and brothels in Rome and Pompeii. What would they have been like on the fringes of the Empire?

In Killing the Hydra, Lucius finds himself alone and in trouble in the Numidian town of Thugga. This is where he meets one of the secondary characters of the book, Dido.

Dido is a Punic girl who has lost her family and is all alone in the world. She is beautiful, and kind-hearted. But in a world where people were desperate to survive, those who didn’t have protection had few choices. For a young beautiful Punic girl on the North Africa frontier, there would not have been many places that offered a roof, a bed, food and clothing.

Wall painting from Pompeii

Dido is a prostitute in the Thugga brothel known as the ‘House of the Cyclops’, and she spots Lucius, a young, good-looking Roman walking by – a sure bet in her eyes, and perhaps better than her usual clientele.

But she doesn’t know Lucius yet. He’s not the average man out for a good time. He has much more pressing issues on his mind as he walks the streets of Thugga.

The ‘House of the Cyclops’ in Thugga, modern Tunisia

When I was doing my research for Killing the Hydra in Thugga (in central Tunisia), Lucius and Dido’s meeting played out in my mind as if they were walking alongside me.

Without giving too much away, Lucius ends up needing this young lupa’s help because he has no one else he can trust.

Can he trust this unknown, Punic girl? Will he go into the lupanar and seek her behind the curtain of her tiny cubiculum?

You have to read the book to find that part out. It is funny how one can find help in the most unexpected places!

One might think that the subject of this particular post was rather fun to write, that the images above are titillating. And sure, they are to an extent. I don’t mind a bit of risqué material on occasion. Why not?

But then, I can’t help thinking of the lives that these female and male prostitutes had to endure. Very few enjoyed the favour of kind wealthy clients, living in luxurious surroundings.

Prostitutes were slaves and most were probably pumped and beaten for a bronze coin or two before having to receive their next tormentor. These people were objects to the rest of the world, not human beings. They were people’s daughters and sons, mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers. In many cases they’d been taken from their homes on the other side of the world. Perhaps they were all that was left of their family?

For most prostitutes in the Roman Empire, life was a living Hades – just something to remember when looking at this aspect of the larger world of Killing the Hydra.

If you are interested in learning more about prostitution in the Roman Empire, the video below is an excellent documentary that will give you an inside look at the Great Lupanar of Pompeii.

Thank you for reading.

https://youtu.be/5uHuFYYO4go