Greetings Readers and History-Lovers!

Welcome you our ninth and final post in The World of The Blood Road!

If you did not see Part VIII on Roman Antioch, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In Part IX we’re going to be taking a look at two of the main historical personages in The Blood Road, Emperor Caracalla and Macrinus, and the unfortunate incidents around their rise and fall.

I hope you enjoy…

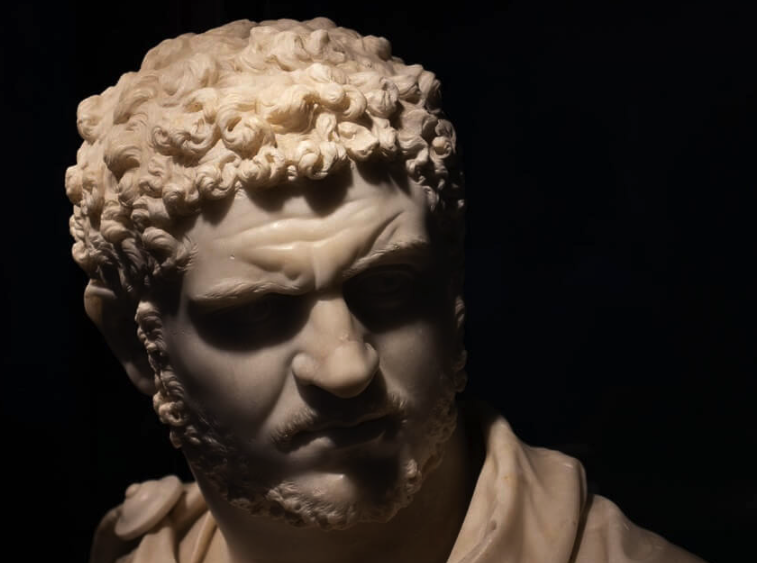

Emperor Caracalla

Each Eagles and Dragons novel has revolved around a particular historical event and or people. In the case of The Blood Road, Caracalla’s short, troubled reign provides the historical backdrop for this story, along with the swift rise and fall of Marcus Opellius Macrinus, newly-made Prefect of the Praetorian Guard.

As we know, Caracalla’s solo reign started in bloody and horrific fashion with the murder of his brother Geta in their mother’s arms. If you can’t recall that event, check out Part I in this blog series.

So what was Caracalla’s reign like once he was sole emperor and his brother’s memory and followers were erased from the face of the Earth?

Veering from murder to sport, he showed the same thirst for blood in this field, too. It was nothing, of course, that an elephant, rhinoceros, tiger, and hippotigris were slain in the arena, but he took pleasure in seeing the blood of as many gladiators as possible…

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, Book LXXVIII)

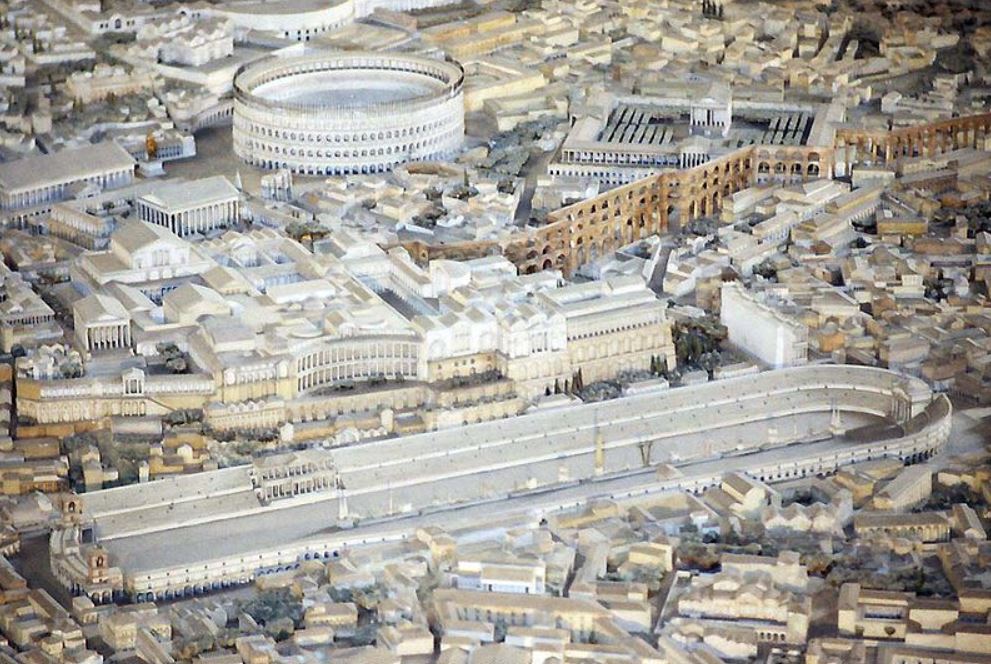

After the murder of Geta and twenty-thousand of his followers, according to the sources, life in Rome apparently became too unbearable for Caracalla who then, according to Herodian, made for the Danube frontier on the northern edge of the Empire.

In Germania, he waged a war against a confederation of the Alamanni, and it seems he felt at home among the troops.

War was what would pre-occupy Caracalla during his reign with much of the duties of correspondence being assigned to his mother, Julia Domna, and Ulpianus.

As we know, the one great legislative deed that Caracalla undertook was the creation of the Constitutio Antoniniana in late A.D. 212 which we discussed in Part III of this blog series. The rest of the time, however, violence seemed to be the order of the day.

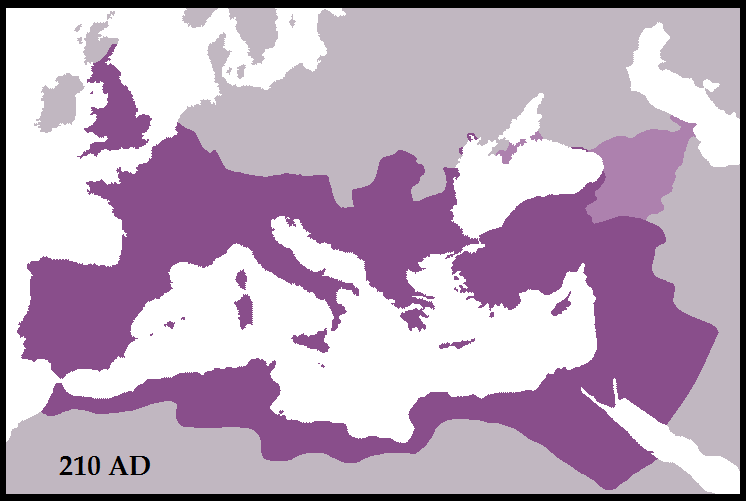

The Roman Empire in A.D. 210, which Caracalla inherited after the death of Severus. Depicted is Roman territory (purple) and Roman dependencies (light purple). (Wikimedia Commons)

From A.D. 213-214, Caracalla campaigned in Germania, content to play the soldier among the men of the legions whom he had greatly enriched. After that campaign, however, he seems to have taken a strange turn and taken on the mantle of Alexander the Great himself. He even made his own pilgrimage to Troy, just as Alexander had.

Caracalla, after attending to matters in the garrison camps along the Danube River, went down into Thrace at the Macedonian border, and immediately he became Alexander the Great. To revive the memory of the Macedonian in every possible way, he ordered statues and paintings of his hero to be put on public display in all cities. He filled the Capitol, the rest of the temples, indeed, all Rome, with statues and paintings designed to suggest that he was a second Alexander.

At times we saw ridiculous portraits, statues with one body which had on each side of a single head the faces of Alexander and the emperor. Caracalla himself went about in Macedonian dress, affecting especially the broad sun hat and short boots. He enrolled picked youths in a unit which he labeled his Macedonian phalanx; its officers bore the names of Alexander’s generals…

…He visited all the ruins of that city [Troy], coming last to the tomb of Achilles; he adorned this tomb lavishly with garlands of flowers, and immediately he became Achilles. Casting about for a Patroclus, he found one ready to hand in Festus, his favourite freedman, keeper of the emperor’s daily record book. This Festus died at Troy; some say he was poisoned so that he could be buried as Patroclus, but others say he died of disease.

(Herodian, History of the Roman Empire, 4.8)

Gold medallion depicting Caracalla as Alexander the Great

Caracalla was obsessed with Alexander the Great, and he would later even make plans to introduce the phalanx into the legions. The troops loved him, but how long would that last?

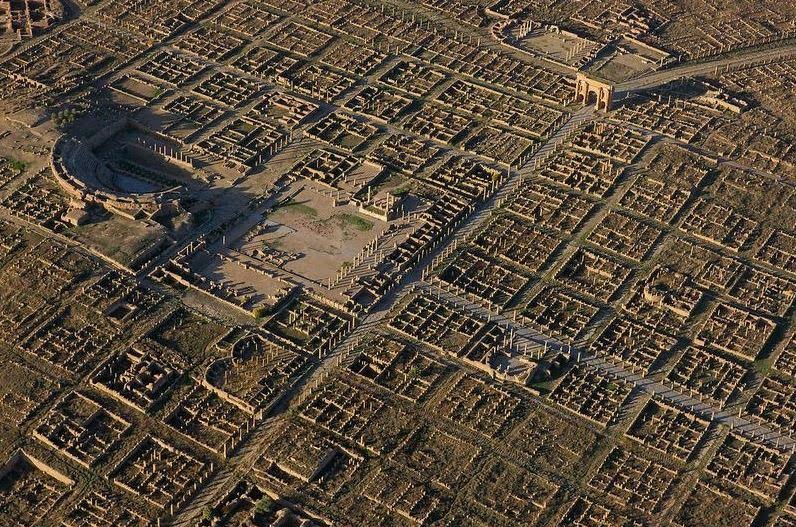

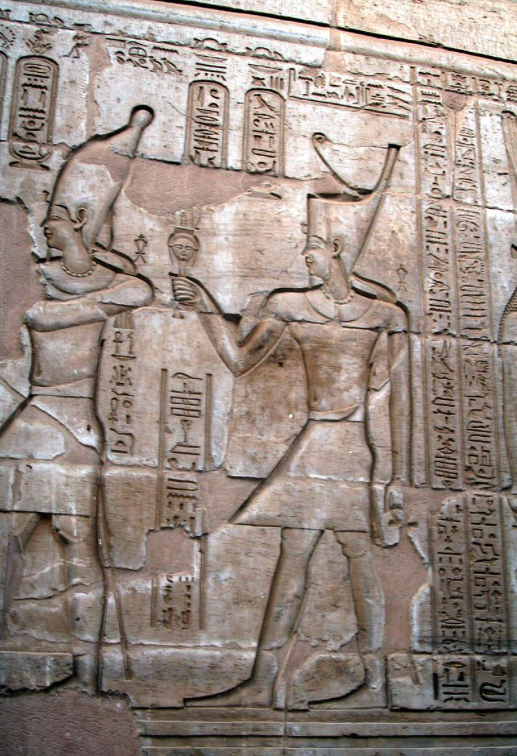

And things worsened in A.D. 215 when Caracalla and his men moved on to Alexandria, the city founded by his hero, where he told the people that he wished to honour Alexander. He was well-received by the Alexandrians, who were not known for holding back their displeasure.

But Caracalla, it seems, had other plans than offering hecatombs of oxen and mountains of frankincense to Alexander. You see, apparently, Caracalla had been widely mocked in Alexandria for the murder of his brother, Geta. Caracalla remembered this, and after he had lulled the Alexandrians into a sense of ease and celebration, he apparently requested that all military aged men be assembled to form phalanxes in honour of Alexander the Great. This is what happened next:

He ordered the youths to form in rows so that he might approach each one and determine whether his age, size of body, and state of health qualified him for military service. Believing him to be sincere, all the youths, quite reasonably hopeful because of the honour he had previously paid the city, assembled with their parents and brothers, who had come to celebrate the youths’ expectations.

Caracalla now approached them as they were drawn up in groups and passed among them, touching each youth and saying a word of praise to this one and that one until his entire army had surrounded them. The youths did not notice or suspect anything. After he had visited them all, he judged that they were now trapped in the net of steel formed by his soldiers’ weapons, and left the field, accompanied by his personal bodyguard. At a given signal the soldiers fell upon the encircled youths, attacking them and any others present. They cut them down, these armed soldiers fighting against unarmed, surrounded boys, butchering them in every conceivable fashion.

Some did the killing while others outside the ring dug huge trenches; they dragged those who had fallen to these trenches and threw them in, filling the ditch with bodies. Piling on earth, they quickly raised a huge burial mound. Many were thrown in half-alive, and others were forced in unwounded.

A number of soldiers perished there too; for all who were thrust into the trench alive, if they had the strength, clung to their killers and pulled them in with them. So great was the slaughter that the wide mouths of the Nile and the entire shore around the city were stained red by the streams of blood flowing through the plain. After these monstrous deeds, Caracalla left Alexandria and returned to Antioch.

(Herodian, History of the Roman Empire, 4.8)

Caracalla as Pharaoh, Temple of Kom Ombo (Wikimedia Commons)

Oftentimes, the sources greatly exaggerate the behaviours of emperors that are perceived to be mad or exceedingly cruel. Is this the case with Caracalla? While it is obvious that neither Cassius Dio or Herodian were fans of the emperor, they do agree on much of what supposedly happened. Considering the murder of his brother, and the undoubted pressure Caracalla felt in perhaps living up to the greatness of his father before him, this was a man who was spiralling out of control and lashing out at the world about him. No matter how many enemies one executed, there were always more waiting in the wings of history.

And Caracalla made more enemies, and sought more war after the massacre at Alexandria when he turned his sights on Parthia.

Once more, hurt feelings and humiliation would sound the drums of war as he sought to go head-to-head with the empire his father had defeated twenty years before. And it all started with a rejected marriage proposal…

After this Antoninus [Caracalla] made a campaign against the Parthians, on the pretext that Artabanus had refused to give him his daughter in marriage when he sued for her hand; for the Parthian king had realized clearly enough that the emperor, while pretending to want to marry her, was in reality eager to get the Parthian kingdom incidentally for himself. So Antoninus now ravaged a large section of the country around Media by making a sudden incursion, sacked many fortresses, won over Arbela, dug open the royal tombs of the Parthians, and scattered the bones about. This was the easier for him to accomplish inasmuch as the Parthians did not even join battle with him; and accordingly I have found nothing of especial interest to record concerning the incidents of that campaign

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, Book LXXIX)

To this point in time, Caracalla’s decisions were anything from rash to ridiculous, and people, including the men of the legions, began to notice. He even began to neglect his Praetorians and legionaries when he appointed a group of freed Scythians and Germans as his new personal guard which he named ‘The Lions’.

He had pushed aside his best advisors, namely Julia Domna and Ulpianus, long ago. So who was with Caracalla throughout all of this?

Marcus Opellius Macrinus, that’s who. But who was this man whom Caracalla made Praetorian Prefect and who would play a crucial role in Caracalla’s downfall?

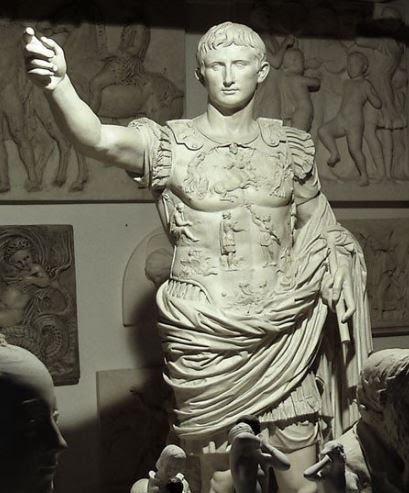

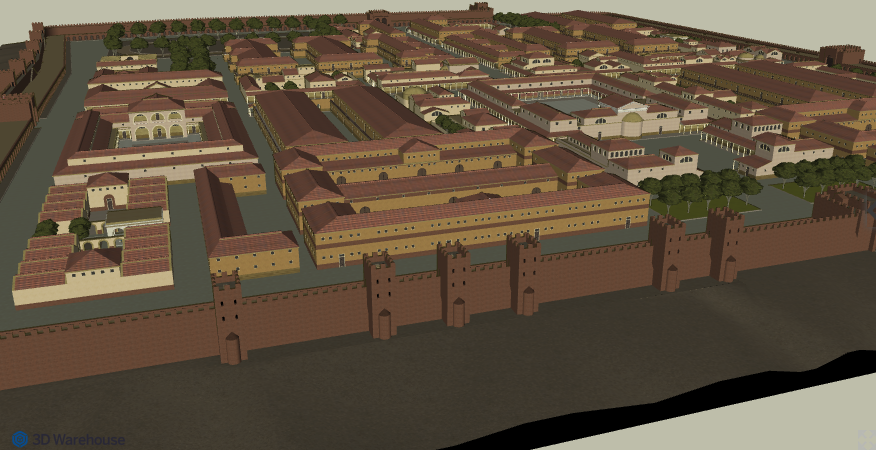

The Praetorian Guard

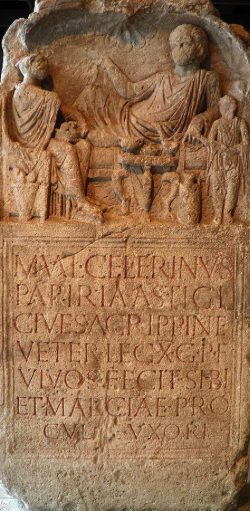

Marcus Opellius Macrinus was born in A.D. 164 in Caesarea, Mauretania Caesariensis. He was from a poor equestrian family, and these humble beginnings fired his ambitions.

Before reaching the heights of power that he achieved, Macrinus was a successful gladiator, a venator (hunter), and a postal courier. He then went to Rome where he became a legal advisor to the infamous Praetorian Prefect under Severus, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus. After the fall of Plautianus, in A.D. 205, under Severus, Macrinus became director of the via Flaminia in Italy, as well as an administrator of Severus’ properties.

He seems to have bided his time until, in A.D. 212, Caracalla made Macrinus Praetorian Prefect. Then, early in A.D. 217, he received ornamenta consularia, ‘consular status’, from the emperor.

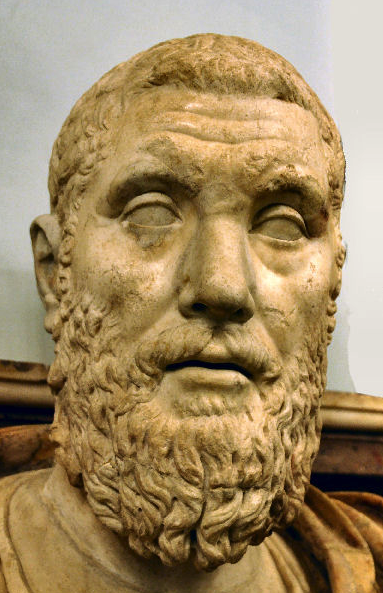

Marcus Opellius Macrinus

As we know, history tends to repeat itself, and there was one thing Caracalla did indeed share with his more successful father: they both trusted the wrong men.

During his reign, Severus had trusted Gaius Fulvius Plautianus, his own kinsman, in the role of Praetorian Prefect. Plautianus had worked against Severus and plotted to overthrow him. We explore this in the book Killing the Hydra.

It seems that Macrinus had learned a thing or two in his time with Plautianus, and as a result, yet again, a Praetorian prefect began to plot against the emperor he served.

With the troops becoming increasingly disillusioned with Caracalla’s behaviour, including his favour shown toward the barbarian ‘Lions’, the time was ripe for a mutiny, and Macrinus seems to have known this.

Caracalla often ridiculed Macrinus publicly, calling him a brave, self-styled warrior, and carrying his sarcasm to the point of shameful abuse.

When the emperor learned that Macrinus was overfond of food and scorned the coarse, rough fare which Caracalla and the soldiers enjoyed, he accused the general of cowardice and effeminacy, and continually threatened to murder him. Unable to endure these insults any longer, the angry Macrinus grew dangerous.

This is the way the affair turned out; it was, at long last, time for Caracalla’s life to come to an end. The emperor, always excessively curious, wished not only to know everything about the affairs of men but also to meddle in divine matters. Since he suspected everyone of plotting against him, he consulted all the oracles and summoned prophets, astrologers, and entrail-examiners from all over the world; no one who practiced the magic art of prophecy escaped him.

(Herodian, History of the Roman Empire, 4.12)

One of Caracalla’s men in Rome tried to warn the emperor of what the astrologers and others had deciphered about Macrinus, as did Julia Domna, but the letters did not reach Caracalla in time.

In the Spring of A.D. 217, it seems the Fates had their blade against the thread of Caracalla’s life. Macrinus had a plan.

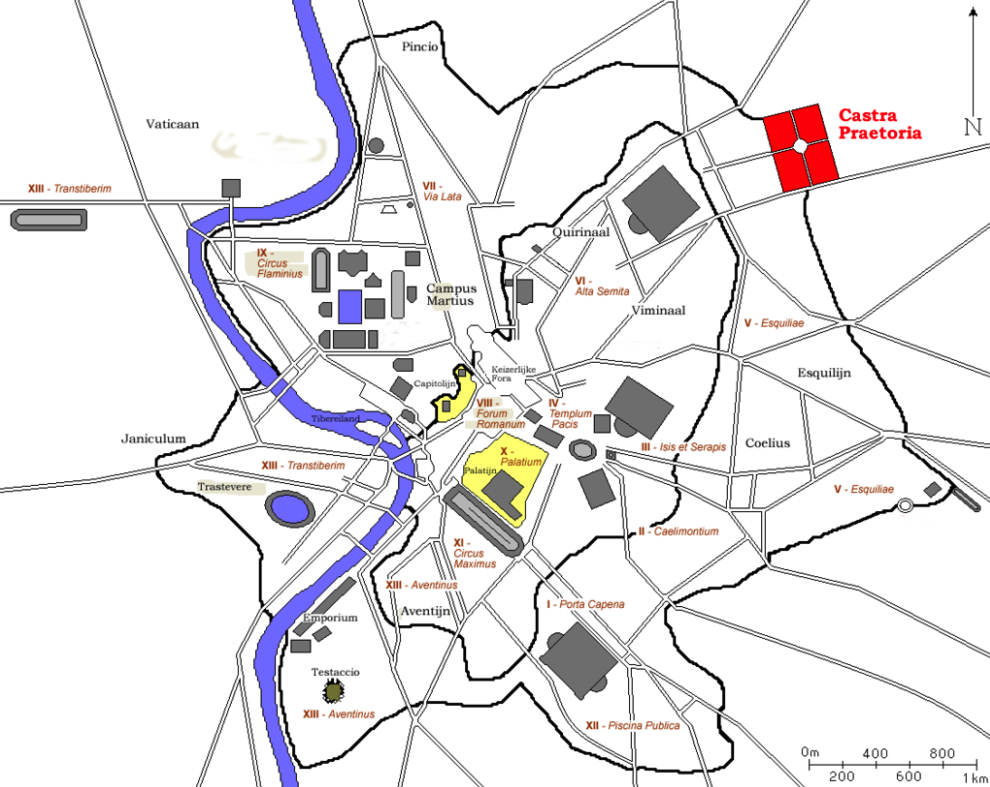

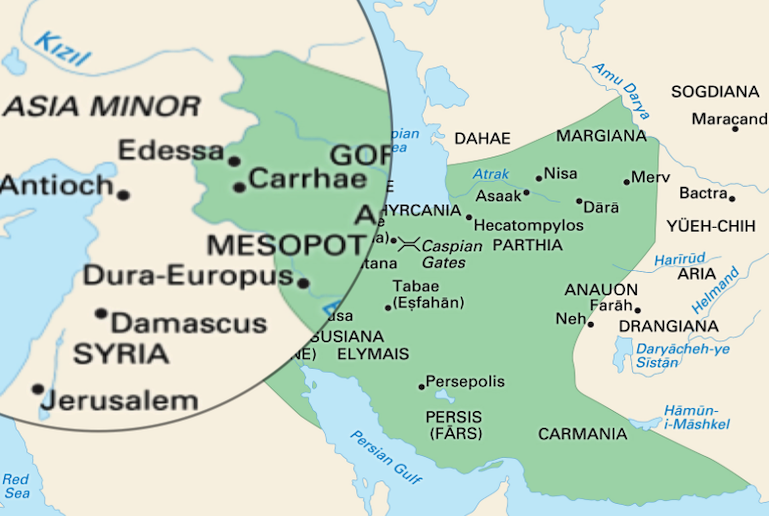

Map of region where Caracalla was on campaign in the final weeks of his reign.

On his way from Edessa to engage the Parthians again, Caracalla decided that he wished to stop at Carrhae, where so many Romans had met their end, to make offerings at the temple of Luna. He would not leave Carrhae…

Macrinus…hastened his preparations, having a presentiment that otherwise he should perish, especially as Antoninus had suddenly, on the day before his birthday, removed those of Macrinus’ companions that were with him, alleging various reasons in different cases, but with the general pretext of showing them honour… Accordingly, he [Macrinus] secured the services of two tribunes assigned to the pretorian guard, Nemesianus and Apollinaris, brothers belonging to the Aurelian gens, and of Julius Martialis, who was enrolled among the evocati and had a private grudge against Antoninus [Caracalla] for not having given him the post of centurion when he asked for it, and so formed his plot against Antoninus. It was carried out thus.

On the eighth of April, when the emperor had set out from Edessa for Carrhae and had dismounted from his horse to ease himself, Martialis approached as though desiring to say something to him and struck him with a small dagger. Martialis immediately fled and would have escaped detection, had he thrown away his sword; but, as it was, the weapon led to his being recognized by one of the Scythians in attendance upon Antoninus, and he was struck down with a javelin. As for Antoninus, the tribunes, pretending to come to his rescue, slew him…

…Such was the end to which Antoninus came, after living twenty-nine years and four days (for he had been born on the fourth of April), and after ruling six years, two months, and two days. At this point also in my narrative many things come to mind to arouse my astonishment. For instance, when he was about to set out from Antioch on his last journey, his father appeared to him in a dream, wearing a sword and saying, “As you killed your brother, so will I slay you”…

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, Book LXXIX)

It was an ignominious end for the son of Severus.

It is this event involving Macrinus, the Praetorian tribunes, Nemesianus and Apollinaris, one Julius Martialis and another with a grievance against Caracalla, that makes up the climax of The Blood Road.

The troops declared Macrinus emperor, and in the aftermath, it is thought that Julia Domna, who was in Antioch at the time, committed suicide rather than be taken by Macrinus. And who can blame this wonderful, intelligent empress? After the key role she had played in the Empire for so long, the death of her husband, and the brutal murder of her youngest son, she must have lost the will to live any longer. The humiliating death of Caracalla was likely, for her, as the dying of the Sun she worshipped.

Once Macrinus was emperor, he struck a deal with the Parthians and made his son, Diadumenian, ‘Prince of the Youth’. He also gave him the rank of ‘Caesar’.

As emperor, Macrinus ruled for just a short year, from April A.D. 217 to June 218. He waged unsuccessful wars and undertook some fiscal reforms that the military, the very men who put him on the throne, did not appreciate.

Gold ‘aureus’ of Julia Maesa

It seems that he also did not account fully for the ambition of Julia Domna’s sister, Julia Maesa, who had bided her time for years, ever a fixture of the imperial court, supportive of her sister and slain nephew.

Julia Maesa, took advantage of the unrest around Emperor Macrinus to instigate a rebellion and have her fourteen-year-old grandson, Elagabalus, declared emperor after the Battle of Antioch on June 8, A.D. 218.

Macrinus was captured and slain in Cappadocia, as he fled for Rome, and his son, whom he had sent to the Parthians for protection, was captured and executed.

The Senate of Rome then declared him and his son enemies of Rome and had their names struck from the records.

So ended the reign of the first, non-senatorial emperor in Rome’s history.

Image of a Roman eagle standard, or ‘aquila’ (Wikimedia Commons)

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this blog series about The World of the Blood Road as much as I’ve enjoyed researching and writing it. There is a lot more history in the book itself, but this will give you a taste of the world in which this adventure takes place.

If you have missed any posts in this blog series, you can read all of them in one place by CLICKING HERE.

While it is true that there are very few primary sources for this period, the ones that we do have – Cassius Dio and Herodian – have shown us once again that sometimes the truth is even more shocking than one could have imagined.

This is a fascinating period in Roman history, and one which I have been very happy to share with you.

Thank you for reading.

The Blood Road is available on-line now in e-book and paperback at major retailers. CLICK HERE to get your copy. You can also purchase directly from Eagles and Dragons Publishing HERE.

If you are new to the Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series, you can check out the #1 best selling prequel, A Dragon among the Eagles for just 1.99 HERE.