Welcome back to The World of Sincerity is a Goddess, the blog series in which we are taking a look at some of the research that went into our latest novel set in ancient Rome.

If you missed Part IV on the Games of Apollo, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In Part V, we are going to be taking a brief look at prostitution in the Roman Empire.

We hope you find it interesting…

WARNING: The topic discussed in this post, as well as some of the images of ancient frescoes shown, may be offensive to some readers. Discretion is advised.

Now, it should be stated at the outset that Sincerity is a Goddess is not an erotic romp through the streets of Rome. It is a heartwarming comedy. However, as mentioned in Part III of this blog series, on humour and comedy in ancient Rome, the prostitute was a stock character in Roman comedic drama.

In truth, you can’t really write about the Roman world without touching on the long-standing role that prostitution and brothels had to play in society. They were a large part of that world, an element of life in ancient Rome that spanned classes.

They existed, and they most certainly flourished. People – that is, men – of all levels of society made it a normal practice to visit their favourite brothel or prostitute.

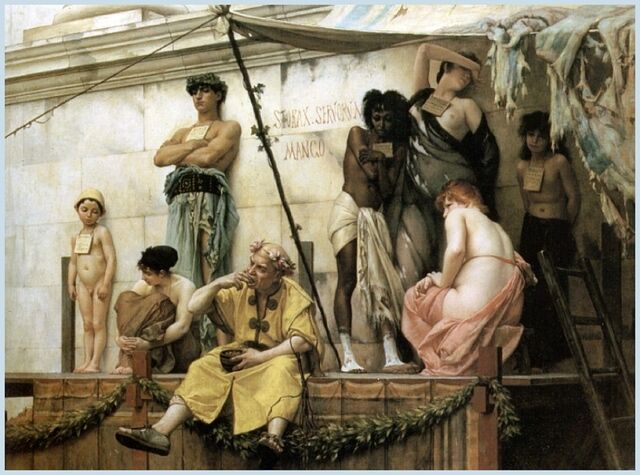

The Slave Market – oil painting by Gustave Boulanger, 1886 (Wikimedia Commons)

If you liked the HBO show ROME – which is fantastic by the way! – you might have an image of Titus Pullo whoring his way through the Suburra with his jug of wine in hand. Certainly, this sort of behaviour was not uncommon, especially for troops fresh back from the wars and looking for a good time.

The flip side might be the richer, upper class nobility who may have believed visiting prostitutes was fine, as long as it was done in moderation and didn’t cause a scandal.

The prostitution scene in the Empire was as large and varied as the workers and clients who kept it running. There was something for everyone!

But let’s look at things a bit more closely.

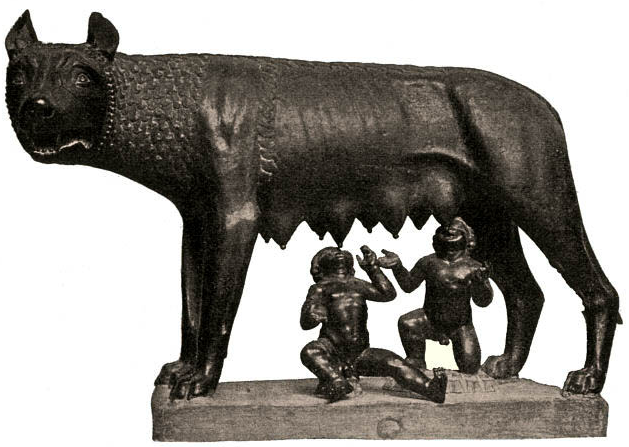

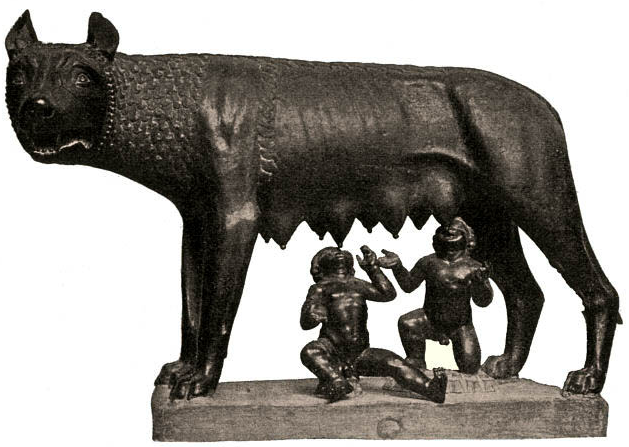

The She-Wolf suckling the brothers, Romulus and Remus

One could say that prostitution has ties to the founding of Rome itself.

You may have read about Romulus and Remus, the brothers who founded Rome and were suckled by the She Wolf, or Lupa.

We have heard of lost children being raised by wolves before, but in the instance of Romulus and Remus, many believe that they were actually raised by a prostitute who found them on the banks of the Tiber. The slang word for prostitute in Latin was lupa.

And the word for brothel was in fact lupanar or lupanarium.

A lupa and her patron

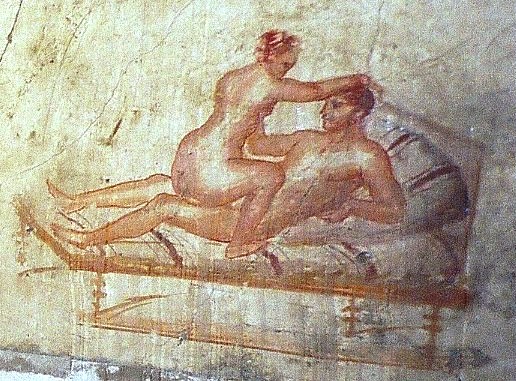

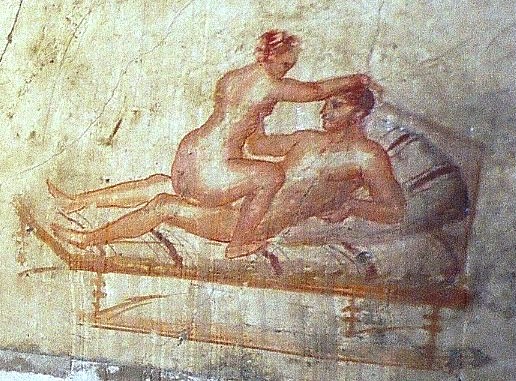

Clients were drawn in by the sexual allure of displayed ‘wares’, sometimes lined up naked on the curb outside, and the various experiences to be had within. The latter were sometimes illustrated in frescoes or mosaics on the walls of the lupanar. These were intended to add to the atmosphere, or were a sort of menu of pleasures to be had.

There were of course ‘high-class’ prostitutes who catered to wealthy and powerful patrons, women who were skilled at conversation, music and poetry. These high end lupae provided an escape, or a feast with friends, in lavish surroundings coupled with a sort of blissful oblivion. Some might have been purchased by their wealthy clients to keep for themselves, and if that was the case they might have ‘enjoyed’ a relatively easy life compared to the alternative.

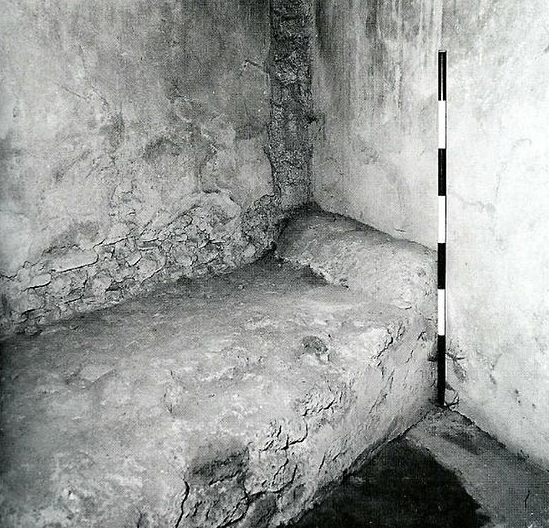

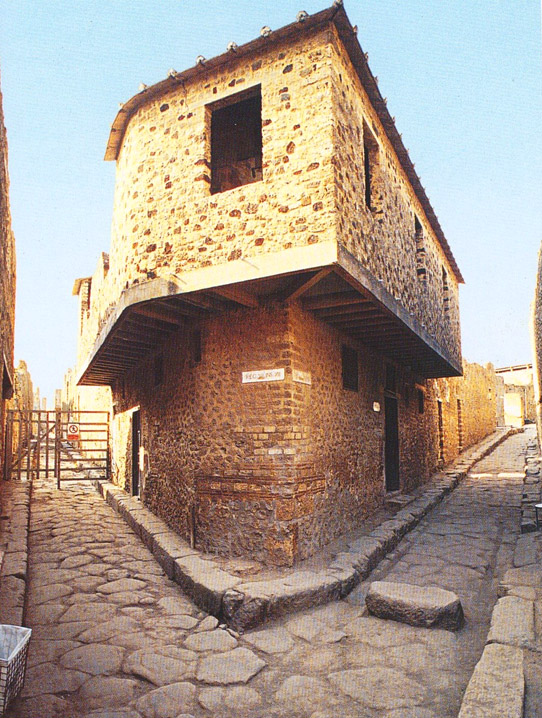

A lupa’s ‘office’ or ‘cell’ in Pompeii – a cement bed that would have been covered with a matress and pillows

The truth for most, however, was that they were slaves. And slaves in ancient Rome, as we all know, were objects, property to be used and disposed of on a whim.

Prostitutes – women, boys, girls, eunuchs etc. – were at the bottom of the social scale, along with actors and gladiators. They could be adored by clients one moment, and shunned the next. And if a lupa was no longer profitable, the leno (pimp), or the lena (madam) might sell them off as a liability, sending them to a life that was possibly even worse.

In ancient Rome, prostitution was legal and licensed, and it was normal for men of any social rank to enjoy the range of pleasures that were on offer. Every budget and taste was catered to, and because of Rome’s conquests, and the length and breadth of the Roman Empire in the early 3rd century, there would have been slaves of every nationality and colour. Clients of the lupanar would have had their choice of Egyptians, Parthians and Numidians, Germans, Britons, slaves from the far East and anywhere else, including Italians.

The decor of Pompeii’s lupanar – a ‘menu’ of sorts (Wikimedia Commons)

However, even though prostitution was regulated, we should not delude ourselves. This was not a question of morality, or curbing venereal diseases. This was about maximizing profit – prostitution was also taxed!

In Pompeii, prostitution became a sort of tourist trade. One theory contends that on the street pavement you just had to follow the phalluses to find the nearest brothel! There were numerous brothels, and that’s not counting the small curbside cells or niches where the cheapest lupae provided quickies to passers-by.

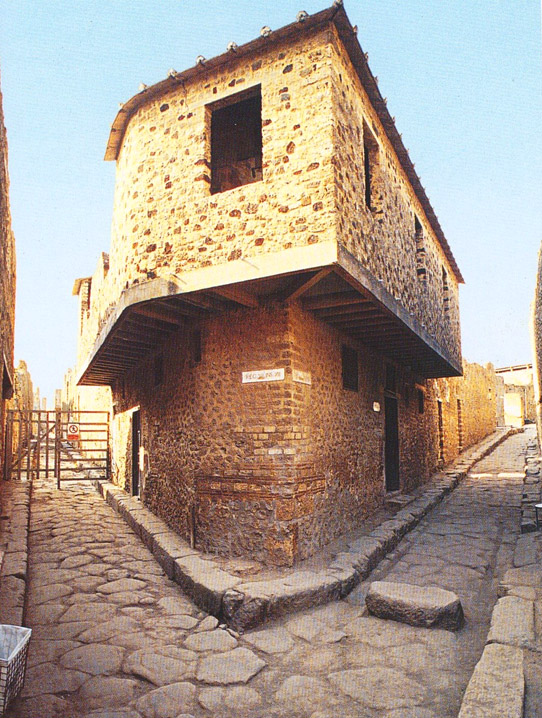

The Great Lupanar of Pompeii

Because of the archaeological finds, the most well-known brothel in the Roman world was the ‘Great Lupanar’ of Pompeii, located at a crossroads two blocks from the Forum. Many of the frescoes pictured here are from that building which had ten rooms, where most brothels had just a few.

A sexual scene from Pompeii’s great lupanar

One might think that the subject of this particular post was rather fun to write about, that the images above are titillating. And sure, they are to an extent. I don’t mind a bit of risqué material on occasion. Why not?

But then, I can’t help thinking of the lives that these female, and sometimes male, prostitutes had to endure. Very few enjoyed the favour of kind and wealthy clients, living in luxurious surroundings.

Prostitutes were slaves and most were probably pumped and beaten for a bronze coin or two before having to receive their next tormentor. These people were objects to the rest of the world, not human beings. They were people’s daughters and sons, mothers, and sisters. In many cases they’d been taken from their homes on the other side of the world. Perhaps they were all that was left of their family?

For most prostitutes in the Roman Empire, life was a living Hades.

Lupanar scene from Pompeii

One thing is certain however. On the whole, prostitutes in the Roman world – be it Rome, Pompeii, or some far flung corner of the Empire – likely led tortured lives, living in squalid conditions while being brutalized by the male population. No matter how much one might like to romanticize the perceived sexual freedom of the Roman world, one cannot escape the fact that this freedom was supremely one-sided.

For some very interesting and sobering thoughts on the subject, watch this SHORT VIDEO interview with historian Mary Beard.

However, as I said, Sincerity is a Goddess is a comedy. The lupa in this book is not a tortured individual, but a more mature and savvy business woman who is quite skilled at reading people. She has, of course, had her share of hardship in her life, but by the time of our story, she has come through her toils a wiser and more confident person. Her character is crucial to the story and the journey one of our protagonists takes.

The Etrurian Players are coming! Brace yourselves!

Thank you for reading.

Sincerity is a Goddess is now available in ebook, paperback and hardcover from all major online retailers, independent bookstores, brick and mortal chains, and your local public library.

CLICK HERE to buy a copy and get ISBN#s information for the edition of your choice.