It’s mid-February now, and with that comes the so-called celebration of love we know today as St. Valentine’s Day. Cards, flowers, and chocolates abound at this time of year. Hopefully there is some poetry too! But the commercialism of it all seems a little strange, doesn’t it? So much so that I know people who are holding ‘anti-Valentines’ celebrations, or ‘Galantines’ for the ladies. Can’t say as I blame them.

I wonder what Valentinus, Bishop of Terni (Interamna), the third century Roman saint for whom this modern celebration is named, would say? He was, after all, martyred in Rome, imprisoned and tortured to death in A.D. 269 and then hastily buried along the Via Flaminia on February the fourteenth. This, for trying to get the emperor to embrace Christianity, or so it is said in one Medieval chronicle.

St. Valentine became associated with courtly love, and was the patron of beekeepers and epilepsy.

I’m all for courtly love, but it does feel like we’ve somewhat lost the thread on the way to the modern age.

St. Valentinus

Our capacity for love, you might say, is one of our greatest attributes as a species, and so it is well-worth celebrating more than one day of the year.

Before celebrations of St. Valentine’s martyrdom on February the fourteenth, Love, the goddess, was celebrated in different ways and guises.

Today, we’re going to be taking a brief look at some of the ways Love was honoured in the worlds of ancient Greece and Rome.

There is a lot we do not know of religious practices in the ancient world. Oftentimes, sources are scanty and there was a lot of regional variation when it came to traditions and honouring the various epithets of gods or goddesses.

The Goddess of Love is no different.

Aphrodite (330–300 B.C.) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

I will sing of stately Aphrodite, gold-crowned and beautiful, whose dominion is the walled cities of all sea-set Cyprus. There the moist breath of the western wind wafted her over the waves of the loud-moaning sea in soft foam, and there the gold-filleted Hours welcomed her joyously. They clothed her with heavenly garments: on her head they put a fine, well-wrought crown of gold, and in her pierced ears they hung ornaments of orichalc and precious gold, and adorned her with golden necklaces over her soft neck and snow-white breasts, jewels which the gold-filleted Hours wear themselves whenever they go to their father’s house to join the lovely dances of the gods. And when they had fully decked her, they brought her to the gods, who welcomed her when they saw her, giving her their hands. Each one of them prayed that he might lead her home to be his wedded wife, so greatly were they amazed at the beauty of violet-crowned Cytherea.

(Homeric Hymn 6, To Aphrodite)

When it comes to love in the world of ancient Greece, there was none other than the Olympian goddess of Love, Beauty, and Fertility: Aphrodite.

She was the epitome of beauty and desire and was worshipped throughout the Greek world, and even influenced her Roman counterpart, Venus. Some believe Aphrodite might have evolved herself from the Mesopotamian goddess of love, Ishtar. She was also associated with the Egyptian goddess, Isis.

In the Greek world, Aphrodite was mainly a goddess of sexual love, generation, and of fertility. However, she was also associated with vegetation, the sea and seafaring (due to her birth from the sea). She was the patron of prostitutes as well and was worshipped as such in ancient Corinth where there was a practice of sacred prostitution in the sanctuary. In that place, according to the Greco-Roman historian, Strabo, the temple prostitutes played a key role in any ceremonies or offerings to honour the goddess.

In Sparta, Cyprus, and the island of Cythera (a mythical birthplace of the goddess), Aphrodite was also worshipped as a goddess of war.

Aphrodite’s legendary birthplace in Paphos, Cyprus (Wikimedia Commons)

As with many gods and goddesses, Aphrodite had a wide array of epithets which reflected many different aspects and traditions. Apart from Love, Aphrodite was also known as Aligena (sea born), Urania (heavenly), Pandemios (popular), Area (armed for war, as consort of Ares), Kourotrophos (nurse), and Epipontia (on the sea).

Gods and goddesses often have symbols that are sacred to them as well. For Aphrodite, two things that were most often associated with her, sacred to her, were myrtle and the dove. The rose too, was sacred to her.

Myrtle, Doves, and Purple Violets

When it comes to specific celebrations in honour of the Goddess of Love in the Greek world, we actually know very little. What we do know with some certainty relates to the Attic festivals.

In the world of ancient Greece, some of the gods’ birthdays were actually celebrated once a month. In ancient Athens, Aphrodite’s birthday was celebrated on the fourth day of every month.

However, the main, annual festival that was held in honour of Aphrodite was the Aphrodisia.

This festival was held in several places, especially in Attica and on Cyprus, during the month of Hekatombaion (July/August). Aphrodite was also worshipped in Cythera, Sparta, Thebes, Delos, and Elis.

The Aphrodisia is specifically mentioned in the sources at Corinth and Athens where prostitutes honoured their patron goddess.

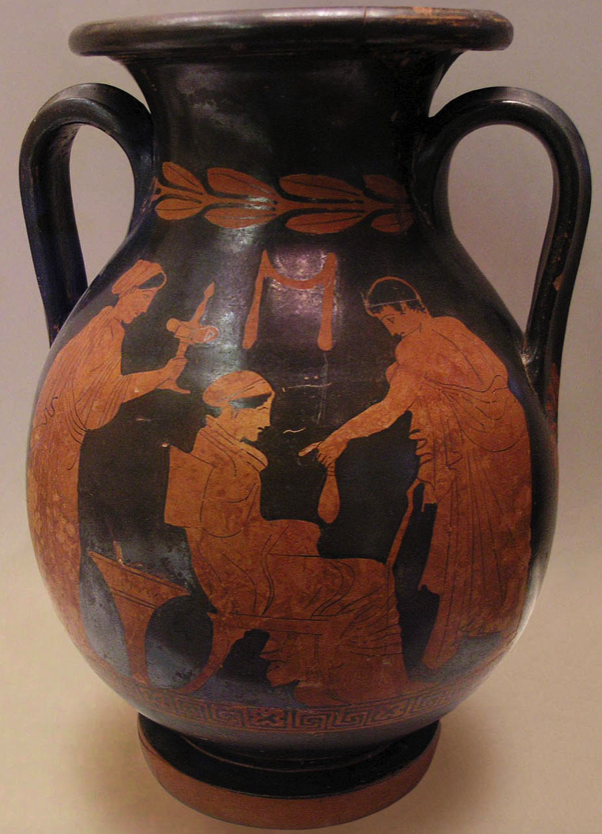

Courtesan and her client, c. 430 BC, National Archaeological Museum of Athens (Wikimedia Commons)

On the sacred island of Delos, the Aphrodisia apparently involved the purchase of ropes, torches and wood.

There are a few rituals around the Aphrodisia that are known to us. Firstly, it seems that temples of Aphrodite were purified with the blood of doves, the bird that was sacred to the goddess. After this, no blood sacrifices (usually male, white goats) were permitted during the festival. The preferred offerings were fire, flowers, and incense.

Celebrations of the Aphrodisia also included processions carrying images or statues of the goddess which were then washed with water. In Cyprus, one of her legendary birthplaces, initiates of the goddess’ mysteries were given salt from the sea, and bread shaped like a phallus.

Temple of Aphrodite, Aphrodisias, Caria (Wikimedia Commons)

Two aspects of Aphrodite indicate the different loves she represented to the Greeks. On the one hand, you had Aphrodite Urania who symbolized spiritual or celestial love. On the other hand, there was Aphrodite Pandemos. This love went beyond sex or romantic love. She represented earthly, non-spiritual love in that it was about civic and interpersonal harmony.

It is believed that the worship of Aphrodite Pandemos was begun by Theseus, King of Athens, who founded her shrine in the agora of the city. In that place, the rituals, once again, included the sacrifice of doves and the washing of the goddess’ statues, but also the coating of the temple roof with pitch and, strangely, the purchase of purple cloth.

Surprisingly, Aphrodite seems to have had fewer festivals held in her honour, compared with her fellow Olympians. However, it would be a mistake to discount this goddess, for she was beautiful and powerful, and could bring as much devastation and she could joy and pleasure. The heroes at Troy could attest to that!

Venus de Milo (Louvre Museum)

Mother of Rome, delight of Gods and men,

Dear Venus that beneath the gliding stars

Makest to teem the many-voyaged main

And fruitful lands- for all of living things

Through thee alone are evermore conceived,

Through thee are risen to visit the great sun-

Before thee, Goddess, and thy coming on,

Flee stormy wind and massy cloud away,

For thee the daedal Earth bears scented flowers,

For thee waters of the unvexed deep

Smile, and the hollows of the serene sky

Glow with diffused radiance for thee!

For soon as comes the springtime face of day,

And procreant gales blow from the West unbarred,

First fowls of air, smit to the heart by thee,

Foretoken thy approach, O thou Divine,

And leap the wild herds round the happy fields

Or swim the bounding torrents. Thus amain,

Seized with the spell, all creatures follow thee

Whithersoever thou walkest forth to lead,

And thence through seas and mountains and swift streams,

Through leafy homes of birds and greening plains,

Kindling the lure of love in every breast,

Thou bringest the eternal generations forth,

Kind after kind. And since ’tis thou alone

Guidest the Cosmos, and without thee naught

Is risen to reach the shining shores of light,

Nor aught of joyful or of lovely born,

Thee do I crave co-partner in that verse

Which I presume on Nature to compose

For Memmius mine, whom thou hast willed to be

Peerless in every grace at every hour-

Wherefore indeed, Divine one, give my words

Immortal charm. Lull to a timely rest

O’er sea and land the savage works of war,

For thou alone hast power with public peace

To aid mortality; since he who rules

The savage works of battle, powerful Mars,

How often to thy bosom flings his strength

O’ermastered by the eternal wound of love-

And there, with eyes and full throat backward thrown,

Gazing, my Goddess, open-mouthed at thee,

Pastures on love his greedy sight, his breath

Hanging upon thy lips. Him thus reclined

Fill with thy holy body, round, above!

Pour from those lips soft syllables to win

Peace for the Romans, glorious Lady, peace!

For in a season troublous to the state

Neither may I attend this task of mine

With thought untroubled, nor mid such events

The illustrious scion of the Memmian house

Neglect the civic cause.

(De Rerum Natura, Lucretius 1.1)

When it comes to the world of ancient Rome, the Goddess of Love seemed to hold more sway over the world than she might have done in ancient Greece.

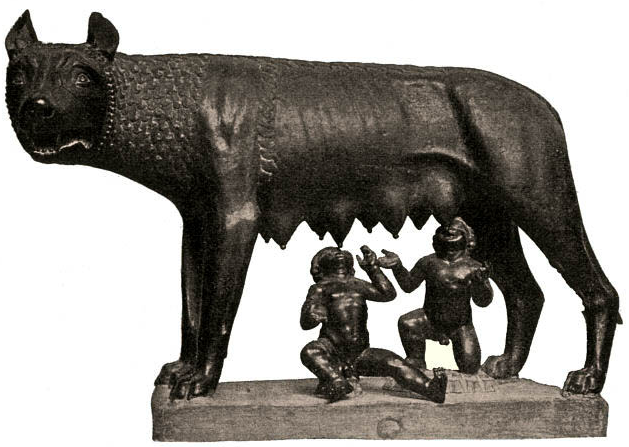

In ancient Rome, Venus was not only the mother of Rome’s mythic founder, the Trojan Hero Aeneas, she was also venerated by some of the most powerful families in Rome’s history, such as the Julii, who claimed descent from her.

It is from the world of ancient Rome that some of the most beautiful words have been written about Love.

But who was the Goddess Venus, and how did she differ from her earlier, Greek counterpart?

Aphrodite and Anchises with baby Aeneas

In truth, Venus was closely aligned with Aphrodite. She even acquired the latter’s mythology such that the two became one over time.

However, before the Greek influence of Aphrodite, Venus was originally an Italic goddess of fertility, vegetable gardens, fruit, and flowers. This is not unlike the god Mars who was also, originally, a god of agriculture before he became the God of War. In Roman religion, Venus and Mars were also consorts, and came to represent the polar opposites of male and female.

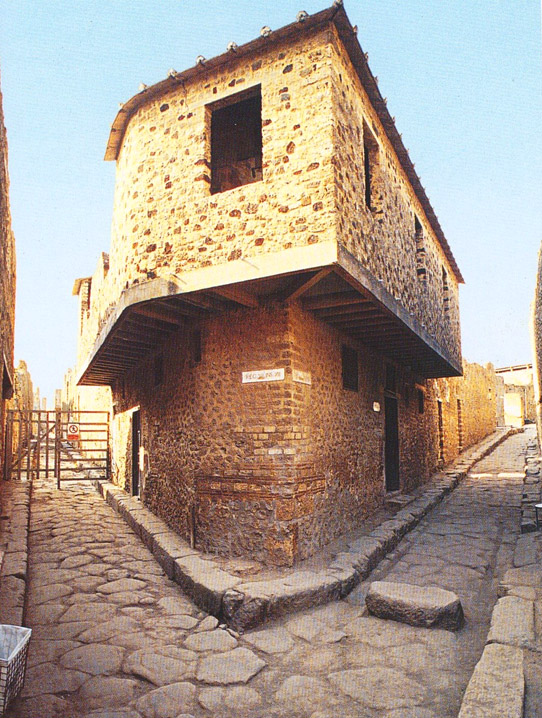

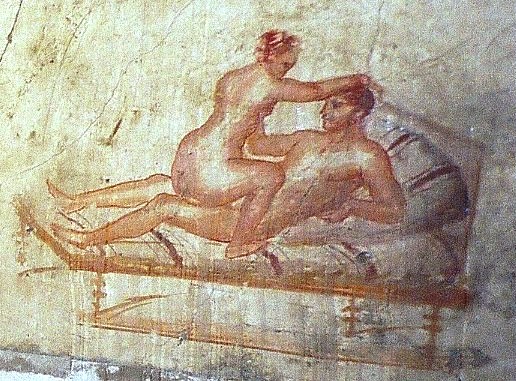

Venus and Mars (mid-1st century CE) from a fresco at Pompeii (Wikimedia Commons)

Like Aphrodite, Venus too had many epithets highlighting the differing aspects of her which Romans worshipped. There was Venus Verticordia (Changer of Hearts), Venus Victrix (Venus Victorious), and Venus Genetrix (Universal Mother). There was also Venus Erycina, who was worshipped at two temples in Rome and was named after a sanctuary on Mount Eryx in Sicily. Her temples were frequented by prostitutes.

Venus Cloacina (Purifier) may have sprung from an earlier water deity, and her statue and shrine were dedicated at the end of the Sabine Wars on the spot where peace was concluded. Thereafter, ritual purifications took place there.

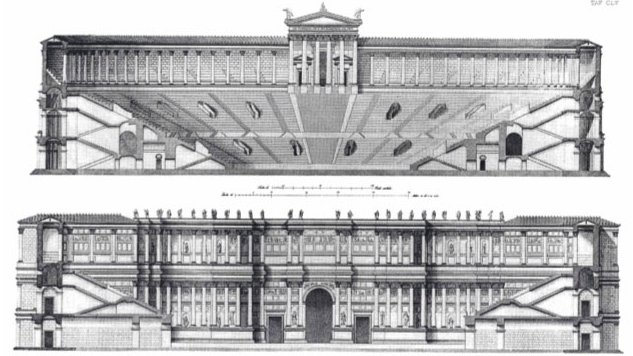

Venus Felix (Favourable) had one of the largest temples in Rome which was built by Hadrian. This was a large double-ended temple with two cellae opposite the Colosseum. It is known today as the temple of Venus and Rome, that is, the temple of Venus Felix and Roma Aeterna.

Venus Libertina (Venus the Freedwoman) is another epithet of the goddess, though some scholars believe this has been confused with Libentina, which means ‘pleasurable’ or ‘passionate’.

Finally, Venus Obsequens refers to ‘Indulgent’ or ‘Gracious’ Venus whose temple was built after the Samnite Wars in c. 295 B.C. at the foot of the Aventine Hill, near the Circus Maximus.

If there was something you could say about the Romans, it is that they loved their festivals. And, unlike the Greeks who seem to have honoured love with just a couple festivals (that we know of) outside her monthly birthday celebrations, the Romans had a few occasions during the year when they honoured Venus.

The biggest festival in honour of Venus, and perhaps the one that you could say is a predecessor to Valentine’s Day, is Veneralia, the festival of Venus Verticordia, the ‘Changer of Hearts’. This festival took place on the Kalends of April (April 1st) and was, supposedly, marked by expressions of love, offerings to the goddess at her shrines and temples, and the ritual washing of the statues or images of Venus herself. The temple of Venus Verticordia in Rome was apparently built in 114 B.C. to atone for the unchastity of three Vestal Virgins who broke their vows.

Fresco from Pompeii

On April the twenty-third came the festival of Vinalia Priora to celebrate wine production. This festival was originally connected with Jupiter, the King of the Gods. However, Vinalia later came to be associated with Venus in her capacity as an agricultural deity or goddess of fertility.

Venus Victrix (Venus Victorious) was important to the Romans and, as such, she was honoured at two festivals in ancient Rome. The first on the calendar was held on the twelfth day of August. This was held from 55 B.C. when the temple of Venus Victrix, built atop the new theatre of Pompey, was dedicated by Pompey Magnus himself. Venus Victrix was also celebrated at another festival on the ninth of October.

Theatre of Pompey with the Temple of Venus at the top of the auditorium. (top centre)

The last major festival of Venus held in Rome was the festival of Venus Genetrix, (Universal Mother). As the divine mother of the Trojan hero, Aeneas, she was considered the ancestral mother of the Roman people, and was worshipped as such.

In ancient Rome, it seemed that not only was the goddess Venus worshipped as Goddess of Love, Beauty, and as the patron of courtesans, she was also worshipped as a bringer of victory, as a divine mother, and also in her original guise as a goddess of the land and fertility.

To the Romans, Love, it seems, had many faces.

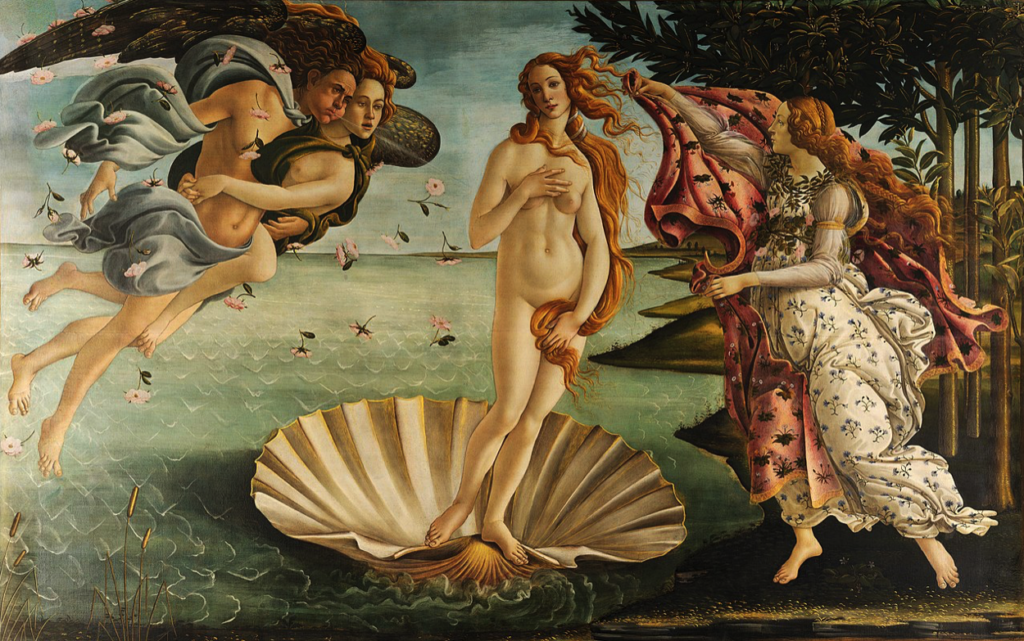

The Birth of Venus (Sandro Botticelli, c. 1484–1486) (Uffizi Gallery, Florence)

Everyone has a different opinion of love, of what love is, its importance in the universe, the world, and in society as a whole. Love has been worshipped as something, or someone, great and earth-shattering, or as something so intimate it can only be spoken of in whispers.

In my opinion, Love makes this life worth living.

It is no coincidence that Love is the inspiration and focal point of some of humanity’s greatest artistic accomplishments, be it in poetry or prose, painting, music, or carefully-shaped marble.

The Goddess of Love, in whatever form she took, or epithet she bore, could be both terrible and beautiful beyond imagining and, as such, She was worshipped and honoured by the ancients throughout the year.

We will leave you now with the words of Ovid, one of the greatest poets of ancient Rome to write about Love…

You, who in Cupid’s roll inscribe your name,

First seek an object worthy of your flame;

Then strive, with art, your lady’s mind to gain;

And last, provide your love may long remain.

On these three precepts all my work shall move:

These are the rules and principles of love.

Before your youth with marriage is oppress’t,

Make choice of one who suits your humour best

And such a damsel drops not from the sky;

She must be sought for with a curious eye.

The wary angler, in the winding brook,

Knows what the fish, and where to bait his hook.

The fowler and the huntsman know by name

The certain haunts and harbour of their game.

So must the lover beat the likeliest grounds;

Th’ Assemblies where his quarries most abound:

Nor shall my novice wander far astray;

These rules shall put him in the ready way.

Thou shalt not fail around the continent,

As far as Perseus or as Paris went:

For Rome alone affords thee such a store,

As all the world can hardly shew thee more.

The face of heav’n with fewer stars is crown’d,

Than beauties in the Roman sphere are found.

Whether thy love is bent on blooming youth,

On dawning sweetness, in unartful truth;

Or courts the juicy joys of riper growth;

Here may’st thou find thy full desires in both:

Or if autumnal beauties please thy sight

(An age that knows to give and take delight;)

Millions of matrons, of the graver sort,

In common prudence, will not balk the sport.

In summer’s heats thou need’st but only go

To Pompey’s cool and shady portico;

Or Concord’s fane; or that proud edifice

Whose turrets near the bawdy suburbs rise;

Or to that other portico, where stands

The cruel father urging his commands.

And fifty daughters wait the time of rest,

To plunge their poniards in the bridegroom’s breast.

Or Venus‘ temple; where, on annual nights,

They mourn Adonis with Assyrian rites.

Nor shun the Jewish walk, where the foul drove

On sabbaths rest from everything but love.

Nor Isis’ temple; for that sacred whore

Makes others, what to Jove she was before;

And if the hall itself be not belied,

E’en there the cause of love is often tried;

Near it at least, or in the palace yard,

From whence the noisy combatants are heard.

The crafty counsellors, in formal gown,

There gain another’s cause, but lose their own.

Their eloquence is nonpluss’d in the suit;

And lawyers, who had words at will, are mute.

Venus from her adjoining temple smiles

To see them caught in their litigious wiles;

Grave senators lead home the youthful dame,

Returning clients when they patrons came.

But above all, the Playhouse is the place;

There’s choice of quarry in that narrow chase:

There take thy stand, and sharply looking out,

Soon may’st thou find a mistress in the rout,

For length of time or for a single bout.

The Theatres are berries for the fair;

Like ants or mole-hills thither they repair;

Like bees to hives so numerously they throng,

It may be said they to that place belong:

Thither they swarm who have the public voice;

There choose, if plenty not distracts thy choice.

To see, and to be seen, in heaps they run;

Some to undo, and some to be undone.

(Ovid, Ars Amatoria, 35)