pyramids

The Pyramids of Ancient Greece

Yes. A pyramid of ancient Greece!

I have something very interesting for you this week.

When most of us hear the word ‘pyramid’, we immediately think of Egypt, of the soaring structures that make up the Giza Pyramid Complex, the pyramids of Menkaure, Khafre, and of course of Khufu, the Great Pyramid of Giza.

These structures have fascinated people for millennia, and not just modern tourists. The pyramids at Giza were a highlight on that famous Hellenistic tourist route we call The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. The Giza pyramids are actually the last on the list that are still standing!

The Pyramids of Giza

But we are not here to discuss Giza or Egypt. Nor are we here to discuss the pyramids of Mesoamerica, those Aztec and Mayan wonders that rise up out of the jungles and plains.

Teotihuacan – Pyramids of the Sun and Moon

Today I wanted to take a brief look at the pyramids of ancient Greece.

That’s right. Pyramids. In Greece.

I don’t know why, but the existence of these only just came to my attention. I had never heard them discussed before, nor seen them in any guidebooks. On one of the ancient history Facebook groups I frequent, someone shared a conspiracy-like video about these.

Now, the video quality was not great, the theories a bit dodgy, but the whole idea of pyramids in Greece piqued my curiosity. So, I did a little digging.

And I found very little.

All of my archaeology and history textbooks make no mention of pyramids in ancient Greece, and most of the websites that mention them were more the sort of New Age pyramid theory sites that you should always take with a grain of salt.

Pyramids in the Movies – Remember Stargate?

However, from the little I was able to find, it seems like there were pyramids in ancient Greece, theoretically about 16, though for most there are no remains, and some may be natural features.

Surprisingly, the one that is best-preserved is near Argos! Now, if you’ve been following me for a while, you’ll know that the Argolid peninsula is the region I frequent most when I go to Greece, so I was shocked when I found out about this.

I was able to get a bit more information from Pausanias, who wrote about these pyramids in his description of Greece in the second century A.D.

On the way from Argos to Epidauria there is on the right a building made very like a pyramid, and on it in relief are wrought shields of the Argive shape. Here took place a fight for the throne between Proetus and Acrisius; the contest, they say, ended in a draw, and a reconciliation resulted afterwards, as neither could gain a decisive victory. The story is that they and their hosts were armed with shields, which were first used in this battle. For those that fell on either side was built here a common tomb, as they were fellow citizens and kinsmen. (Pausanias; Description of Greece 2.25)

So, according to Pausanias, who wrote many hundreds of years later, this pyramid was believed to be a tomb or monument to the fallen Argive soldiers in the opposing armies of Proetus and Acrisius. We’ve seen in other cultures that pyramids have been used as tombs, such as Egypt and even Rome, so that is consistent.

Pyramid of Cestius, Rome

Now, Proetus and Acrisius were brothers, sons of Abas and Aglaea, and mythical kings of Argos. Proetus was king first but after many battles with Acrisius, and subsequent losses, went into exile. Acrisius became King of Argos, and this is the same Acrisius who banished his own daughter, Danae, to the sea, along with her infant son – you guessed it! – Perseus.

Acrisius putting Danae and the baby Perseus into the box before throwing them into the sea

I managed to find a theoretical list of the pyramids in Greece, and it seems that many of them are located in the Argolid. They are the Pyramids of Hellinikon, of Kampia, of New Epidaurus, of Ancient Epidaurus, of Ligourio, of Dalamanara, of Nafplion, two at Fichthia and Mycenae, and the pyramid of Neapolis.

I have my doubts about this list, and was not able to find any information on most of these. Ligourio came up, and I have indeed driven through that village many times, and stopped at the Mycenaean bridge that is near there.

Mycenaean between Naufplio and Ligourio

However, the one pyramid whose remains are the most intact, and for which there is the most information, is the Pyramid of Hellinikon near Argos. It is believed that this is the pyramid referred to by Pausanias above.

Entrance to the Hellinikon Pyramid

In truth, nobody is really certain of the age of this pyramid, or the one at Ligourio. There is no exact date for the battle between the legendary kings of Argos, Proetus and Acrisius. Another battle mentioned in the sources, in which a large number of Argive soldiers died, apparently took place in c.669 B.C.

It seems that as far as history and sources, the evidence is pretty thin. This is when archaeology and dating can help us, or, in this case perhaps, hinder us.

From what I’ve read, the dating of the Hellinikon pyramid is highly controversial. On the one side we have the legend mentioned by Pausanias. Then, in 1937, excavations were undertaken by the American School at Athens in which they found pottery ranging from the proto-Helladic period to the Roman period. This shows the site was in use for some time, but what about dating?

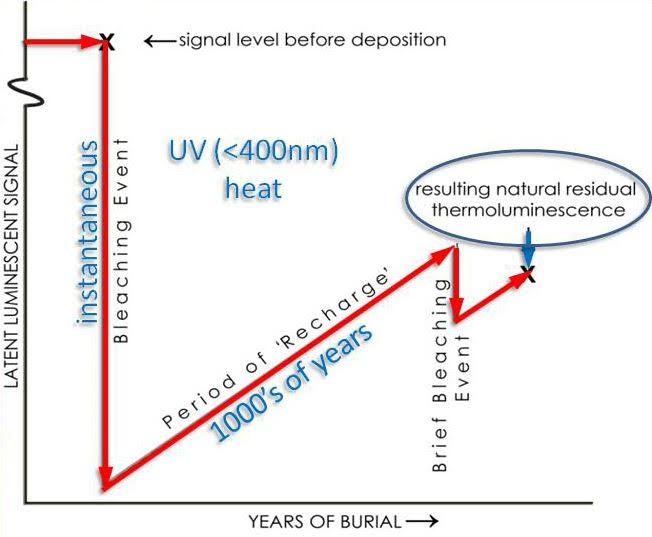

A look at Thermoluminescence dating

There is a method of dating called thermoluminescence dating, and this was carried out on the pyramid of Hellinikon. Without going into too much detail about this, this method of dating measures the accumulated radiation in objects or sediment. Click here to read more about the methodology behind thermoluminescence dating.

The team that carried this out, in addition to geophysical surveys, excavations, and a study of the masonry of the pyramid, dates the Hellinikon to the period of about 2000-2500 B.C.

That’s also about contemporary with the pyramids on the Giza plateau.

But this dating method has been highly criticized as inaccurate and sloppy, with one camp of academics taking shots at the group that undertook the study of the pyramid. Other groups believe the style of masonry sets the Hellinikon pyramid in the Classical period.

If you’re confused, you’re not alone. I’d be curious to read an impartial study of the Hellinikon and other pyramids of the Argolid and ancient Greece.

That’s the funny thing about pyramids… You either have groups whose goal is to prove their existence in relation to something else, like extraterrestrial life, or other groups whose sole purpose seems to be to disprove the work of the previous groups.

Uhm… Run for it!

The fact is though, that the Hellinikon pyramid exists and is a unique and fascinating structure in an ancient landscape.

Was it a war memorial? Was it a tomb? Was it a guard house with a small garrison of Argive soldiers? Or was it a landing beacon for the ships of little green men?

Who knows?

Hellinikon from above

The confusion and disagreement around these structures doesn’t negate the fact of their existence. They may not be as flashy as the pyramids of the Aztecs, or as gloriously huge as those in Egypt, but they are indeed fascinating.

When it comes to ancient mysteries like these, personally, I find it sad when individuals try to ‘explain away’ such things.

In no way am I suggesting alien linkages – though I have spoken with people who claim to have seen UFOs in the sky when they were attending a night performance at the ancient theatre of Epidaurus – but the ancient Greeks did have close trading ties with the Egyptians.

These sorts of finds are gold for writers. After all, I’ve always found it more interesting to explore possibilities than to disprove theories, and fiction is the perfect medium for that!

Thank you for reading.

Hellinikon interior corridor