Roman Empire

Io Saturnalia! – Celebrating ‘The best of days’ in Ancient Rome

Happy Saturnalia, everyone! Or, as the Romans said, Io Saturnalia!

December 17th was the official start of Saturnalia in the Roman Empire, and for seven days the Roman world, and especially Rome itself, experienced what can only be described as a carnival atmosphere.

Just as Christmas is a time of year that many people look forward to, so too was Saturnalia for Romans, free and slave.

Today we’re going to take a brief look at some of the customs that surrounded this ‘the best of days,” as the poet Catullus called it.

Saturnalia was basically a winter solstice festival in honour of the god Saturn, the chthonic (of the earth) Roman god of seed sowing, who was often equated with the Greek god Cronus. As an agricultural deity, his symbol was a scythe.

The primary temple for this Roman deity was at the foot of the Capitoline Hill, across from the Rostra, the Temple of Concord, and the arch of Septimius Severus.

The festival of Saturnalia was originally a single day, but eventually ran from December 17th to December 23rd, ending on the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, or the birthday of the Unconquerable Sun. The three days from December 17th to the 19th were considered to be legal holidays on which no work was done. Schools, gymnasia and courts were closed, and no war was waged.

Saturnalia was a sacred time of year in the Roman calendar, but oddly enough, there is no single, full description of the festival. What we know comes from various references in ancient sources, mainly Macrobius whose work on Roman religious lore is set during the festival.

So, what do we know about the festival of Saturnalia, and what traditions did people keep at that time of year?

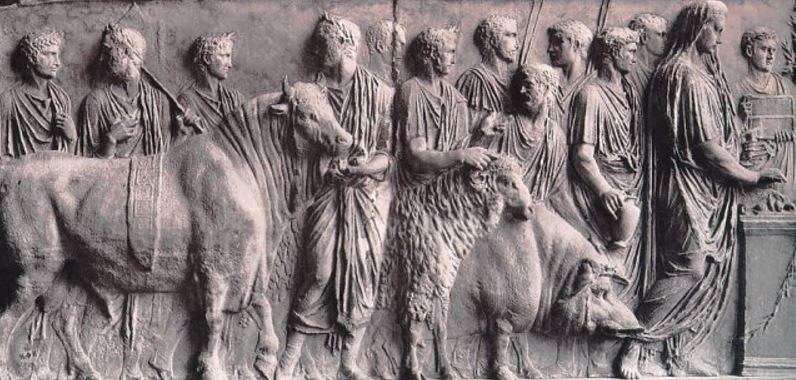

In ancient Rome, we know that the festivities began on December 17th with a sacrifice at the Temple of Saturn in the Forum, in which the priest performed the ceremony in the Greek fashion, ritus Graecus, with his head uncovered. In the temple, the feet of Saturn’s statue were normally bound up with wool, but for Saturnalia, the wool was removed, and some believe this symbolized the liberation that many felt during the festival.

After the sacrifice, which may have been a suckling pig, there followed a grand public banquet, or convivium publicum, which was paid for by the state. A statue of Saturn was placed upon a couch for this event so that the god could preside over the festivities.

As a festival of light, or the solstice, wax candles, or cerei, were lit everywhere and given as gifts. The light may also have been considered a symbol of the quest for knowledge and truth, something to go along with this season of hope for many in the dark days of winter.

Another symbol of the season was holly, which was considered sacred to Saturn. Sprigs of this were also given as token gifts. Many other gifts were given at this time of year, mainly on December 19th, which was the day of the sigillaria, the day of gift-giving.

In addition to wax candles, gifts could include pottery, writing tablets, dice, knucklebones, combs, toothpicks, hats, knives, lamps, balls, perfumes, and toys for children. If you were among the rich, exotic animals or slaves might even be given!

Figurines were also a gift that was given, and these have something of an interesting history. One thought is that this particular gift stemmed from the giving of toys to children. However, another, darker possibility for the giving of figurines is that they were intended as substitutes for the human blood offerings that may have originally been offered to the earth god Saturn, in the early days of Rome, perhaps in the form of gladiatorial combat to the death.

Some sigillaria were similar to the gifts we get in Christmas crackers today, but they could be much more elaborate too.

In addition to the public celebrations of Saturnalia, the festivities continued at home.

On December 18th and 19th, domestic rituals of the family were observed, such as bathing, and the common sacrifice of a suckling pig to Saturn.

Gifts were given among the family on the day of the sigillaria, but also in the days to come.

One interesting tradition was that the usual clothes worn by Romans, such as the toga or plain tunica, were discarded during Saturnalia in favour of colourful clothes known as synthesis, which were a mish-mash of patterns and colours. They were the Roman party clothes of Saturnalia! Along with the synthesis, Roman men also wore a felt or leather conical cap known as a pileus.

Saturnalia was a time of role reversal, a time when the opposite of normal was acceptable.

For instance, during Saturnalia gambling was permitted in public, with the stakes being either coins or, oddly enough, nuts!

Overeating and drunkenness were common, as was guising, which was the wearing of masks or costumes to take on another persona.

Thou knowest not what evening may bring.

(Macrobius. Saturnalia)

However, perhaps the most commonly known tradition of Saturnalia was the role reversal of masters and slaves. Traditionally, masters would serve their slaves a meal of the sort that they would usually enjoy, sigillaria would be given, and the slaves were even at liberty to insult their masters without fear of retribution.

Citizens or slaves might even be elected the ‘King of Saturnalia’ at the banquet at which time they could give absurd orders that had to be obeyed.

If this seems like a hectic summary with myriad different traditions and goings on, you’d be right. Just as with Christmas today, everyone likely had their own unique take on the traditions of the season. Roman religion was highly customizable!

You’d also be correct in assuming that some of the traditions of Saturnalia feel very familiar. At Christmastime, people eat and drink more than is usual (if they are so fortunate), there are a couple of days off work, gifts are given, holly (and perhaps ivy) is hung, candles are lit, and more.

Around the winter solstice, it seems that many cultures and religions find cause to celebrate.

So, from December 17th this year and in the run-up to Christmas, spare a thought for the Romans who certainly knew how to throw a good party this time of year.

Thank you for reading, and Io Saturnalia!

For those of you who are fans of historical fantasy set in ancient Rome, you may want to check out one of Eagles and Dragons Publishing’s latest releases, Saturnalia: A Tale of Wickedness and Redemption in Ancient Rome.

Much of the research for this post was done for the writing of this new book, so if you would like to see many of these ancient traditions come to life, you’ll want to check it out by CLICKING HERE.

Lastly, and for a bit of fun at this festive time of year, check out this hilarious video and song by the Ashmolean Latin Inscriptions Project and members of Oxford’s Faculty of Classics:

Ancient Everyday – Food and Dining in Ancient Rome – Part II

Welcome back, Romanophiles!

In part one of this two-part series on food and dining in ancient Rome, we looked at the various foods that would have appeared on the tables of average Romans and how this varied depending on economic status or geographical region. If you missed that post CLICK HERE to read it.

This week, in part two, we’re going to take a brief look at the eating habits and formalities of dining in ancient Rome.

When it comes to eating, we seem to have inherited some of our modern-day habits from the Romans.

They normally ate one large, main meal a day, along with two smaller ones. However, the ientaculum, that is, breakfast, to the Romans, was not the most important meal of the day as we are sometimes told. In fact, Romans might have skipped this altogether before heading down to the Forum or visiting with clients or benefactors.

Breakfast in ancient Rome was light, and most likely involved puls, a sort of porridge, or some bread, perhaps dipped in honey or olive oil. They didn’t attack the day with a lumberjack breakfast in their stomachs!

In the early days, the midday meal or lunch, known as the cena, was the main, large meal of the day. This would perhaps have coincided with the sexta, the sixth hour of daylight or siesta time of day. For more about the Roman siesta, CLICK HERE.

Lastly, the Romans would have enjoyed a lighter evening meal called the vesperna, perhaps involving bread and cheese, or some fruit.

Sensible eating for those early Romans!

Over time, however, the midday lunch became a lighter meal known as the prandium, and the cena, the main meal, was moved to the evening.

For the poor, most meals would have consisted of puls or bread, sometimes with some sort of meat, or vegetables if they were available. There was certainly less variety among the different meals of the day if one was not wealthy or at least well-off.

For the rich and well-to-do, things were different. As the cena was the large meal of the day it would have included three courses of food.

The first course was the gustatio or promulsis, and this would have involved appetizers of olives, eggs, raw vegetables, and simple fish or shell fish.

The second, or main course, the prima mensa, often included cooked vegetables and meats, the types and amounts varying greatly, depending on the occasion and wealth of the family or individual.

And lastly came the sweet course, the secunda mensa. This is when fruit and sweet pastries would have been served.

But what about the etiquette of dining? What was the etiquette? How did they sit? Did the Romans just move from course to course, gobbling up all that was placed before them?

Not exactly. In fact, there was a rigid system of seating, or placement. Contrary to modern views, most Romans ate while sitting, but when it came to the wealthy, they tended to recline on couches, especially at dinner parties.

At a banquet, or convivium, there would also have been entertainment between courses, perhaps by clowns, dancers, or readings by poets.

Food was eaten with fingers, and cut with knives. Spoons were also used, but forks were not.

Today, when one attends a dinner, there are sometimes places assigned to guests. There might even be name cards, and some hosts might distance themselves from their least favourite guests at the table.

Well, this was also true in ancient Rome!

I want you to imagine you’re invited to an evening cenaat a senator’s home. You’re greeted in the atrium and led through the house to the dining room, the triclinium, just off of the peristyle garden. It’s dark out, and the scent of lemon blossoms and jasmine are on the night air. After a cup of watered wine, you’re shown into the triclinium by one of the well-dressed slaves who shows you to the couch known as the lectus medius, the middle couch of three, the couch of honour.

At this point, you’re very happy, for your host, seated with his wife on the lectus imus, the low couch, has honoured you above all other guests. The other guests behind you grin and bear it as they are shown to the high couch. From where you are, you have a wondrous view of the night garden and all of the other guests, and conversation comes easily, for you do not have to twist and turn.

Sound like a good evening? It could be. But the Romans took seating of this sort very seriously.

Horace (65 B.C. – 8 B.C.), in Satire VIII presents us with a scene depicting the seating arrangements and the trials of being a host in ancient Rome:

‘I was there at the head, and next to me Viscus

From Thurii, and below him Varius if I

Remember correctly: then Servilius Balatro

And Vibidius, Maecenas’ shadows, whom he brought

With him. Above our host was Nomentanus, below

Porcius, that jester, gulping whole cakes at a time:

Nomentanus was by to point out with his finger

Anything that escaped our attention: since the rest

Of the crew, that’s us I mean, were eating oysters,

Fish and fowl, hiding far different flavours than usual:

Soon obvious for instance when he offered me

Fillets of plaice and turbot cooked in ways new to me.

Then he taught me that sweet apples were red when picked

By the light of a waning moon. What difference that makes

You’d be better asking him. Then Vibidius said

To Balatro: “We’ll die unavenged if we don’t drink him

Bankrupt”, and called for larger glasses. Then the host’s face

Went white, fearing nothing so much as hard drinkers,

Who abuse each other too freely, while fiery wines

Dull the palate’s sensitivity. Vibidius

And Balatro were tipping whole jugs full of wine

Into goblets from Allifae, the rest followed suit,

Only the guests on the lowest couch sparing the drink.’

Seems like Horace had a lot of fun with this, and his satires are certainly good for a laugh! I do feel for that host.

But what was all this ‘status seating’ about?

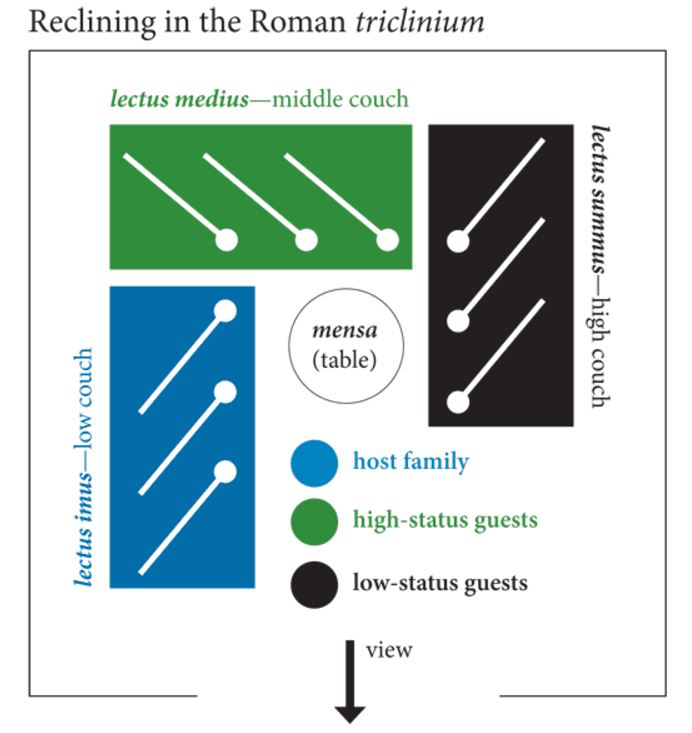

In a relatively well-off Roman household, three couches in a triclinium were standard. These were arranged around a low table, or mensa, and these couches had specific names and purposes.

The lectus medius, the middle couch, was the couch of honour, and was where important guests were placed. Because of its position, guests seated here were able to talk easily with other guests and had the best view, whether onto a peristyle garden or some sort of rural landscape.

The lectus imus, the low couch, was reserved for the hosts. It allowed them to speak with the high status guests on the lectus medius, and also the guests sitting directly across on the lectus summus.

Last and least, the lectus summus, or the high couch. This was not like the high table at a wedding today. No. The lectus summus in ancient Rome was the opposite. It was reserved for the lower status guests, maybe even for children if they were permitted to attend. This couch possessed less of a view, though still allowed its occupants the chance to participate in the conversation, though they might have had to turn awkwardly to do so. If you were shown to the lectus summus, then it seems you knew your place at the gathering.

If it was a rather large banquet, we can assume that the farther from the hosts and guest of honour you were on lectus summus side of the triclinium, the less important you were considered, or at least less influential.

Plan of typical Roman couch placement in a triclinium (from Reclining and Dining (and Drinking) in Ancient Rome by Shelby Brown; The Iris – Behind the Scenes at the Getty)

I hope you’ve enjoyed this two-part blog series on food and dining in ancient Rome.

In researching this for the books Saturnalia: A Tale of Wickedness and Redemption in Ancient Rome, and the forthcoming title Isle of the Blessed, I found that some of the modern perceptions we have about Roman banquets are indeed true, while others are clearly not. If one was eating in a tenement in the Suburra, you were not reclining on a couch eating grapes and drinking wine. It was a table and chair for you.

The food consumed, as well as the eating and dining habits of the poor and the rich were often separated by a wide gulf. Nevertheless, the wonderful colour and variety of the world of ancient Rome never ceases to delight me!

More Ancient Everyday posts will be along in the future, but in the meantime, may your winter dining be pleasant.

Thank you for reading.

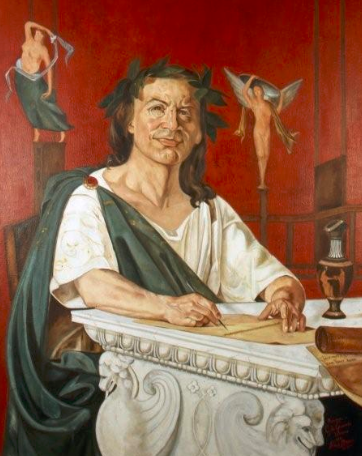

Do YOU have what it takes to become the next Emperor?

Salvete, fellow Romanophiles!

This week on the blog we have a special guest post by author, game designer, and all-around Roman history-lover, Ben Joshua.

As many of you know, though I spent many years in the academic world, I also believe it is important to nurture a love of history through popular culture. This is often done through television, movies, and popular fiction.

But there is another area in which folks can meet history face-to-face, or even take part in it…

I’m talking about gaming, Role Playing Games to be precise, or RPGs.

This is a somewhat new area for me, so I was fascinated when I found out how Ben translated his love of the Roman world and history into a fresh new gaming environment that will, from the sound of it, suck you right in.

So, strap on your lorica segmentata, and grab your gladius! Let’s see if we all have what it takes in the world of Immortal Empires…

Take it away Ben!

Do YOU have what it takes to become the next Emperor?

By: Ben Joshua

That’s the question many of us, in our ambitious youth, ask ourselves. Of course, we might not aspire to become Princeps, but we do aspire to become something (great). I admit I did. My studies at West Point helped me to appreciate how the Roman war machine, with its state-of-the-art legion structure, gave them victory after victory on the battlefield. From there, I began to admire Imperial Rome in its entirety: military strategy, architecture, government (our Congress derives from their Senate), and especially their culture of strong, independent women and the conniving men who love them (or was it the other way around? LOL!).

My interest deepened years later when it dawned on me that Jesus Christ was born during the Pax Romana, and later crucified during the reign of Tiberius Caesar, and how utterly significant that was! That Tiberius’s reign of terror made senators shake for fear of being thrown off the Tarpeian Rock for imagined treason…well no wonder Pilate shuddered and finally caved when the Jews insinuated he would not be a friend to Caesar if he let Jesus live! That realization blew my mind; Roman history had suddenly become one of my favorite hobbies.

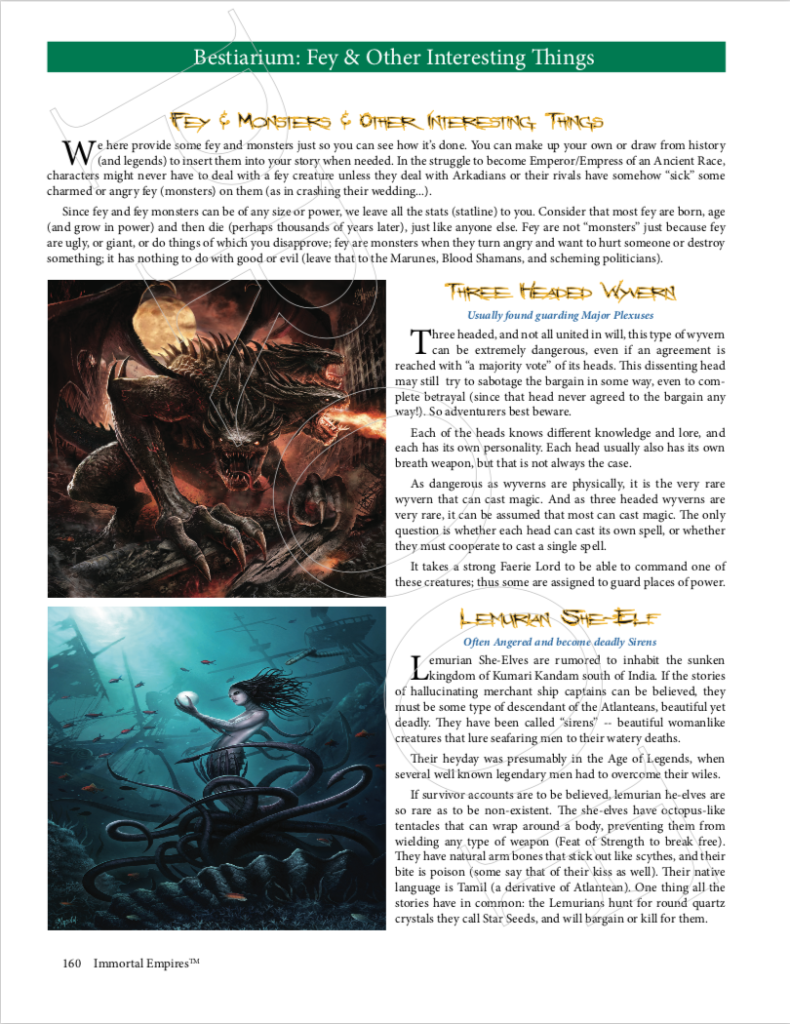

So when my friend Clay, a Jewish Romanophile, invited me to help develop a game he hoped would bring Imperial Rome to life, I jumped at the chance. What we developed was a phenomenal game system of esoteric delight that celebrates the ruthless political intrigue of a magical and immortal, Imperial Rome. The object of the game is to become Emperor/Empress by any means possible. We called the game: Immortal Empires Role-Playing Game for Mature Players.

Immortal Empires Role Playing Game for Mature Players is a tabletop Role-Playing Game designed especially for Romanophiles like us, as well as stalwart RPG’ers who may never have been enthusiastic about Roman history (but who will be educated by the game). It can also be played over the internet using Skype, zoom, or any other camera-based communication platform.

Set in the backstabbing era of Imperial Rome, players must manipulate their characters to power through webs of Romanesque intrigue. Magic, fey, the undead, and immortals that your enemies might send against you all complicate your ascent. Defeat them, outwit the enemies who sent them, and you can become the next Princeps!

The game is definitely not a watered-down role-playing game. There are myriad ways to tweak your character. It also builds vocabulary (Latin and English), hones simple math skills, educates on historical events and milieu, and emphasizes problem solving in a mature (and oftentimes scheming) way. The game system, developed for over 15 years, relies on ten-sided dice for random generators (attacks, skills rolls, etc.). It has an open magic system (create your own spells to do what YOU want them to do), a whopping ten major (and magical) fighting arts (with over 375 unique powers), hundreds of Talents, Traits and Flaws, and so much more.

Even better, a series of novels set in the game world help you get to know the “official storyline” personalities and milieu, with more on the way. They tell the story of one Thascius Gildo’s rise to power, without ignoring the struggles of other powerful women and men vying for dominance.

If you’re the storytelling type, you can become The Storyteller, bringing your players through the story you’ve prepared for them. You, the Adept Romanophile, can decide to make your story about Personalities your players must outwit, or about an event in which they play a starring role. You decide how much actual history you want to insert into the game, as you challenge your players to rise to power in spite of the obstacles you place before them. You’ll have to be prepared for your players trying to outwit you at every turn, because you’ll be role-playing the game world personalities they meet.

The game assumes every major civilization is at its own zenith of power (with the very magical Ancient Races ruling). It takes the most interesting events and items from our history and allows you to insert them into your Story. The exact details are left to you; but there are spathas, onagers, triremes, togas, cognomens, frumentarii, fgens in Rebus, senators, the Cursus Honorum (and Militim, Scholasticus), Imperium, and so much more.

While your players might have to deal with undead and fey abominations, these are generally not considered the true enemy (that would be too adolescent a game, in our opinion). Instead, the true enemy might consist of that powerful senator (played by the Storyteller) who is trying at every turn to ruin your house by sleeping with your spouse. Or, perhaps even more sinister, the elusive enemy might be the friendly player sitting next to you, whom you trust as she smiles at your every suggestion but is plotting to assasinate your pater familias! Does anyone remember Brutus…?

This sophisticated game is generally not for the uneducated. It is not for children. It is assumed that there will be adult situations in your scheming and betrayals as you gather power through subterfuge and with Machiavellian supremacy. Hence, the two core game books (The Storyteller’s Codex and The Adventurer’s Rulebook) are written for you, the highly educated reader, who understands innuendo and nuance.

We at subrosa.games are striving to get Immortal Empires RPG into the hands of more Romanophiles so we can build a fun community of players and storytellers, Emperors and Empresses, who enjoy challenging each other’s intellects while immersed in a milieu we love. We hope to some day have conventions (Saturnalias?) and tournaments. We hope to some day help direct films with great actors and actresses set in accurate, if magical, panoramas of the majesty of Imperial Rome.

Dreams, certainly. For now, we just want to let you know the tabletop version is available, as are three novels (I’m writing book 4 now): Mirror Motives, The Starborn War, and Keeper of the Myst. We are working on our websites that we hope to have interactive in the coming year (so that people can network with each other to find gaming sessions and storytellers).

Subrosa.games and ImmortalEmpires.com are currently under development (but you can sign up on ImmortalEmpires.com to receive an invite when we’re done). We’re thinking about setting up a GoFundMe or similar page once the websites are done; rewards for contributions would take the form of game books, novels, and free online memberships. We are also looking for angel investors who share our greater vision.

I don’t want it to sound like a sales pitch, but if you are interested in trying it out, you can start playing the game now by ordering the two core books from Amazon.com. These are beautiful 8.5×11 Hardcover books with full color printing on quality paper. Even if you’re not a role-player-gamer, you might still enjoy the novels.

Thank you in advance for your support. When we launch the websites, we’ll need you as seasoned Storytellers and Players to show other intelligent schemers how to properly play Immortal Empires — the Roman way!

Sincerely and with profound respect and gratitude to Adam and his fans for letting me share this guest blog post.

Ben (Maximillian Rufus, Legate, in the “Official Story”)

The author grew up an avid reader and writer, served as Vice President of the Wargames Committee at the United States Military Academy at West Point, and later as a military intelligence officer stationed in Germany. He currently lives a quiet life with his dog, writes novels and music, and serves from time to time as Project Director for a small development company. He enjoys oil painting, Roman architecture and history, reading over-the-top historical fiction, and playing saxophone to EDM and smooth jazz.

I’d like to thank Ben for taking the time to tell us about his RPG game set in the world of ancient Rome.

I’m not a hardcore gamer myself, but after reading about this, I just might become one!

A virtual life in the Roman Empire?

Yes please!

For those of you who are interested, be sure to head on over to www.immortalempires.com to sign-up for the mailing list and receive all the updates on the game.

Sounds like this is going to be a wild ride!

Cheers, and thank you for reading.

Ancient Everyday – Marriage and Divorce in Ancient Rome

Salvete, history-lovers!

Are you married? Are you divorced? Do you have children? Have you remarried?

These questions are normal enough today, as they were in ancient Rome. Marriage and divorce were common in the ancient world. We’ve inherited them from our ancient ancestors, but with some tweaks to how they are perceived, their sanctity, and the laws surrounding them.

As ever, the Romans did things a little differently than we do today.

On this edition of Ancient Everyday, we’re going to take a brief look at marriage and divorce in ancient Rome.

With respect to character or soul one should expect that it be habituated to self-control and justice, and in a word, naturally disposed to virtue. These qualities should be present in both man and wife. For without sympathy of mind and character between husband and wife, what marriage can be good, what partnership advantageous? How could two human beings who are base have sympathy of spirit one with the other? Or how could one that is good be in harmony with one that is bad? (Gaius Musonius Rufus)

When it comes to ancient Rome, more is known to us about the families of the upper classes regarding marriage and divorce.

Marriage was central to Roman life, and at the heart of Roman virtues. At one point, as we’ll see, it was even a legal duty!

As in ancient Greece, Roman marriages were always monogamous. That’s not to say Roman men did not have mistresses, slaves or prostitutes, but they were only permitted one wife.

Also, a full Roman marriage was possible only if both parties were Roman citizens, or if they had been granted a conubium, permission to marry.

Officially, men were permitted to marry from fourteen years of age, and women from the age of twelve. This seems inconceivable to us, and it may also have been so for Romans since in actual practice, marriage did not usually take place until after twenty years of age.

Before a marriage could take place, there was a formal betrothal known as a sponsalia. This could take place, especially among the upper classes, when the children were young, and was arranged by the father of each family, the paterfamilias. To read more about the paterfamilias in ancient Rome, CLICK HERE.

Before about 445 B.C. Patricians were not permitted to marry Plebeians, and a free person could not marry a freedman or freedwoman, although this last point was altered by the legal changes instituted by Emperor Augustus – except for senators! More on the changes Augustus made shortly.

When we think of marriage in ancient Rome, we often have a perception of marriage only for political reasons or some other gain. This was certainly true among the nobles of Rome.

However, marriage was in fact a private act most of the time. It required the following: the consent of bother partners (though still dictated by the paterfamilias of each family), the living together of the man and woman with the intention of forming a lasting union, and sometimes a dos, or dowry.

Whereas today, when a man and woman get married, they sign a registry along with their witnesses, there was no prescribed formula or written contract in Roman weddings, except in the instance where a dowry was offered.

Furthermore, the marriage ceremonies had no legal status. They only indicated that a marriage now existed, the same as a dowry. Both were moral, rather than legal, requirements.

When a woman got married in the early days of Rome, she was supposed to go from her father’s house, under his control, to her husband’s house and control, in manu mariti. However, by the end of the Roman Republic, a woman, though married, remained in the control of her father, sine manu, for as long as her father lived.

A Roman woman was not absorbed into a husband’s family.

Changes were certainly afoot in ancient Rome when it came to marriage, and by the reign of Augustus and the beginning of the Empire, marriage became unpopular and birth rates dropped.

This crisis of the Roman population is what led Augustus to create reforms around marriage laws.

Augustus decreed that all men between the ages 25 and 60, and women between 20 and 50, had to marry and have children.

The emperor also instituted the ius trium liberorum, the right of three children, which instituted privileges for parents of three or more children. Some of these privileges included being excused from some civil duties, or being permitted to receive inheritances intended for their children.

So what did a Roman wedding look like?

Weddings were more religious than legal in ancient Rome. They had to take place on an auspicious day, and not on the Kalends, Nones, or Ides of any month, nor during the months of May and February. June was the preferred month for marriages.

A conferatiowedding ceremony was the most serious, oldest, and most solemn of Roman weddings. It was attended by the Flamen Dialis (High Priest of Jupiter), and the Pontifex Maxiums (High Priest of the College of Pontifs), and during the ceremony the sacred panis farreus, or spelt bread, was shared. It was nearly impossible to become divorced if you were married in conferatio.

But the average Roman wedding ceremony was of a less severe nature.

At the average Roman wedding, the auspices were taken to ensure it could proceed with the gods’ blessing. There was a sacrifice of an animal, such as a pig, and then there was a banquet, or convivium. Afterward, the bride and groom might exchange gifts.

There were roughly three stages to the ceremony. First, there would be a ceremony in the home of the bride. Then, there would be a procession of both families to the home of the groom where a banquet would be served at the husband’s expense.

Marriage was all well and good for the Romans, but what happened when things soured? How did they deal with divorce?

Well, as it turns out, the Romans had a much more relaxed view when it came to divorce than we do today. We actually know a bit more about Roman divorce than we do about marriage.

Unlike certain faiths today, especially since the Middle Ages, there was no religious ban on divorce in ancient Rome.

Perhaps more importantly, there was no social stigma attached to it, or to a divorced spouse.

In the early days of the Republic, a man could divorce his wife on the grounds of adultery, but the same did not go for the woman. In ancient Rome, it was accepted that men would have mistresses, concubines, and frequent the brothel, or lupanar.

A man could also divorce his wife if she was thought to be infertile. This was obviously long before thinking around lazy sperm or sterility in men!

However, the women of Rome must have rejoiced in part when, during the late Republic, men and women could initiate divorce without having to give a reason!

Men who do not like to see their wives eat in their company are thus teaching them to stuff themselves when alone. So those who are not cheerful in the company of their wives, nor join with them in sportiveness and laughter, are thus teaching them to seek their own pleasures apart from their husbands. (Plutarch)

In ancient Rome, divorce was actually common, especially among the upper classes who often used marriage as a way to solidify political alliances, depending on which way the wind was blowing.

It is estimated that 1 in 6 Roman marriages ended in divorce in the first ten years, and that 1 in 6 marriages ended through the death of a spouse.

The good news for Roman women was that upon divorce, a woman’s dowry was to be returned.

But what happened after divorce?

Well, as often happens today, people did remarry. It was a frequent occurrence, but sadly, it appears to have been more socially acceptable for men who could remarry with ease, whereas it was more difficult for a woman to remarry after a divorce.

If one was a widow, it was actually made law by Augustus’ reforms that you were required to remarry!

We’ve only really scratched the surface of marriage and divorce in ancient Rome here, but I hope it has given you an idea of that part of the ancient everyday lives of Romans.

We’ve focussed more on the ceremonial and standard practices around weddings, as well as the laws around marriage and divorce. However, one thing we have not looked at is the human element.

It’s all fine and good to have the laws or rules for such things jotted down on a piece of papyrus, or upon the surface of a wax tablet, but at the end of the day, the strengths and weaknesses, personalities and passions, of the individuals involved would have made marriage and divorce in ancient Rome as vast, varied and confusing as it is today. Perhaps more so?

This was just another look at how the everyday life of Romans was similar, but at the same time, different, to our own.

Thank you for reading.

Roman Ghosts – Sentries of the Saxon Shore

Salvete, Readers!

Today we have our second post in the Roman Ghosts series, and this one is guaranteed to give you shivers.

If you missed the first post about Shades in Eburacum, you can check it out by CLICKING HERE.

Many of you have written to us about Roman ghost sightings in the UK, and we are keen to research them and share with everyone. Rest assured, they’re all on the list! Today’s post comes by way of a tip from Eagles and Dragons reader, Michael Dennis.

This particular look at Roman ghosts takes us to Reculver on the Kentish coast in England, in particular a site on the promontory at the mouth of the Watsum Channel, facing the Isle of Thanet.

Before we get into the spectral sightings associated with this remote location, we should, of course, look briefly at the history of the place.

Reculver was the site of Roman Regulbium which comes from the Celtic name meaning ‘at the promontory’.

It was on this site during the Claudian invasion of Britain in A.D. 43 that a Roman fortlet was first built. Tense times in the land, of course. Eventually, the fort was connected by road to the settlement of Durovernum, modern Canterbury.

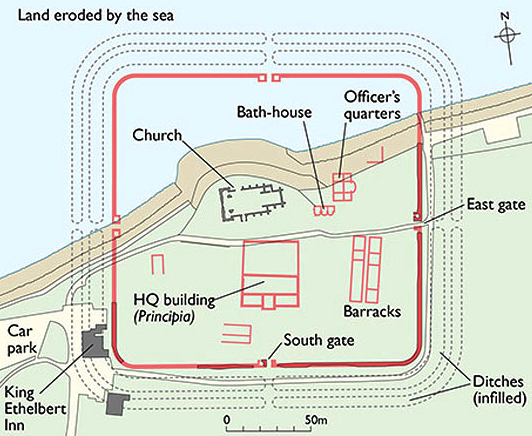

Eventually, in the late second century, a larger Roman castrum was built on the site, and this included a basilica as part of the principia (headquarters building), barracks, a bathhouse, and even a nearby oven which was located outside the walls. The walls themselves were almost fifteen feet high and ten feet thick. Sadly, much of the fort has been lost to the sea and erosion.

What does remain are two of the Roman towers which were incorporated into the early medieval Saxon church of St. Mary’s. More on these towers later…

The Notitia Dignitatum, the great Roman administrative document of the early fifth century, indicates that the Cohors I Baetasiorum was stationed at Regulbium. These troops of the Baetasii tribe inhabiting the lands between the Rhine and the Meuse, in Germania Inferior, were a good distance from their homes.

Regulbium was apparently abandoned after A.D. 360, but from what we have been reading, it may well be that some of the troops never went home.

Try and imagine a soldier, or a cohort of soldiers, based in a specific location for an extended period of time. Routine and disciplina, as the Romans called it, were central to a soldier’s life. Sometimes they lived and died in a specific place, had families, lost loved ones, took life and shed blood.

Well, in Regulbium to this day, it seems that some of the Roman soldiers are determined to keep to their schedules and their posts.

There have been many reports of Roman soldiers seen on patrol at Reculver fort (Regulbium) or keeping ghostly sentry duty there, so much so that visitors, even in summer, claim that there is something very ‘wrong’ about the place.

Apparently, the site of the Roman fort is so haunted that it has become a destination for amateur ghost hunters!

But it isn’t just the ghosts of groups of Roman soldiers on patrol that people have reported seeing. There have also been chilling reports of a lone Roman soldier standing stolidly at his sentry post somewhere between the two remaining towers that stand there to this day.

What might the shade of that Roman be looking out for? A returning patrol? Raiding Saxon ships coming into the isle between the fort and Thanet?

Who knows? One thing is for sure, there are more than just the shades of Roman soldiers lurking around the fort.

There have also been numerous reports of phantom babies crying on the wind when people have visited the fort!

One might think that this is just the gusting wind playing tricks on visitors to the fort. Then again, perhaps not.

When excavations were carried out at the fort, the burials of ten infants were found within the fort itself, and six of these were associated with specifically Roman buildings.

There are some theories that the infants were part of a ritual sacrifice there, but it is not known if they were dead already (stillborn), or if they were killed as part of the ritual.

Seeing as Romans more or less frowned on human sacrifice (apart from in the arena), the slaying of babies does seem to be a bit of a stretch, but one never knows. Perhaps the Baetasii tribe from the Rhine region did that sort of thing, perhaps not.

Either way, the remains of infants have been found, and whatever the circumstances of their deaths, it seems likely that the wailing of their little shades at the fort would be enough to turn the legs of the toughest legionary to mush.

Have you been to the ruins of Regulbium? Would you go after reading this?

I’m not sure I would.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this second post in the Roman Ghosts series. For more information on the haunted site you can check out the book Haunted Kent, by Janet Cameron.

For information about the archaeology and ruins of Roman Regulbium, you can check out the Historic England page by CLICKING HERE.

Remember, if you know of any Roman ghost stories in any part of the former Roman Empire that you would like to share, just send us an email through the Contact Uspage of the website and we’ll look into it.

Thank you for reading!

Ancient Everyday – Pets in Ancient Rome

Salvete Romanophiles!

We’re back for a new Ancient Everyday post. If you missed the last one on coinage in the Roman world, you can check it out HERE.

This week, we’re looking at pets in the Roman world, and let me tell you, this turned out to be a much bigger, more complex topic than I had imagined! So, this will be something of an introduction to a topic that could well take up an entire book.

A quick shout-out to Jenny Villar who suggested this topic.

The first thing most of us picture when we think of animals in ancient Rome is no doubt the display bloody entertainment in amphitheatres like the Colosseum. But that is only part of the picture.

Before we discuss household pets, we should first take a look at the relationship ancient Romans actually had with animals.

Romans, it seems, were absolutely fascinated with animals!

They also had a strange, contradictory relationship with animals. They admired and were in awe of wildlife, and yet they used them to death, quite literally.

Animals served many purposes in the Roman world.

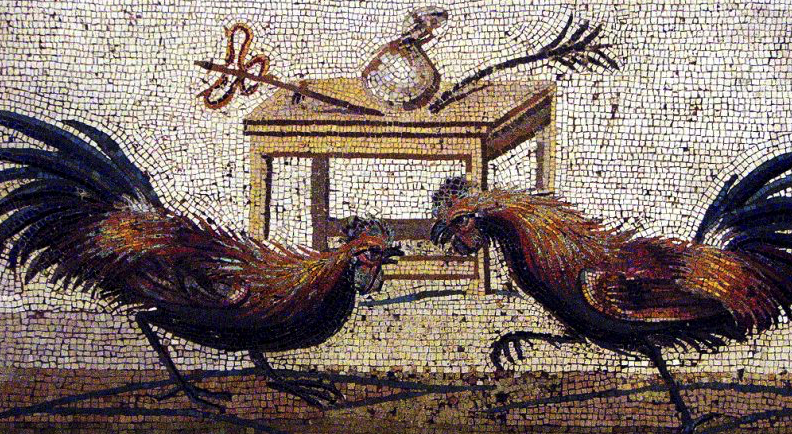

We have already alluded to entertainments in the amphitheatres and circuses of the Empire where any number of grisly pairings of beasts took place. But this category would also have included using animals for hunting (as both hunter and prey), in the wild or in the arena. Romans loved to watch animals be hunted, fight, and be killed, whether in the amphitheatre, or a private cock-fighting pit.

Animals were also labourers in the city, the countryside, and in the ranks of Rome’s legions across the Empire as beasts of burden and more.

One area that is sometimes overlooked is the use of animals for religious purposes. Animals were sacrificed to the gods on a daily basis for a variety of reasons, and were often specifically bred for this purpose. As examples, only the whitest of doves might have been offered to Venus, Goddess of Love, or the blackest of sheep to chthonic gods such as Dis.

Animals were also used as ornaments in the Roman world, especially in the homes and villas of the rich and powerful. The emperors Domitian and Caracalla are both said to have had pet lions that followed them around, and some wealthy Romans even had elephants, the most exotic symbol of Roman power, to transport them to dinner parties.

What the valet slave would do with that, I don’t know!

What seems apparent is that exotic animals were as much a show of Roman wealth and power as the most expensive jewels, and some rich Romans had gardens filled with various exotic animals – a sort of ancient equivalent to a nineteenth-century menagerie.

Included in the long list of animals that appeared in the amphitheatres or homes of the Roman world were parrots, ostriches, monkeys, lions, leopards, lynxes, tigers, elephants, rhinos from Asia and Africa, and more.

But we’re here to discuss animals as pets, specifically. In doing so, we might expect the usual array of animals we’re familiar with today, but, as ever, the Romans have put a twist on things for us. For instance, some children were said to have had pet goats or deer who were sometimes hooked up to little wagons or carts to pull them around.

We’ll go through a few of the animals that were said to have been kept as pets in ancient Rome.

Snakes. Let’s just get this one out of the way now. Yes. The Romans had pet snakes. In fact, the idea of a household with a resident snake is quite ancient.

In the ancient world, snakes were not only useful in destroying vermin such as mice and rats. They were also sacred, and strongly associated with healing. Think of the god Asclepius who is often pictured with a snake around a staff, that symbol which has been adopted by the medical profession.

In ancient Greece, many households had a snake which acted as a sort of household guardian. In fact, in certain parts of the Mediterranean to this day, it is considered bad luck to kill a snake.

In ancient Rome, emperors had sent to Epidaurus and the Sanctuary of Asclepius there for some of the sacred snakes used in healing, and these were kept on Tiber Island. The emperors Tiberius, Nero, and Elagabalus all kept snakes.

Now, whether or not the residents of Suburan tenement blocks kept snakes, I’m not sure. One hears of people with pet snakes today, so I imagine the idea is not so far-fetched.

Fish were also kept as pets, but these appear to have been something relegated to the upper classes who had the space and land for large fish ponds. One wonders how attached some became to these fish, for surely they would have ended up on the tricliniumtable at some point.

Sparrow! my pet’s delicious joy,

Wherewith in bosom nurst to toy

She loves, and gives her finger-tip

For sharp-nib’d greeding neb to nip,

Were she who my desire withstood

To seek some pet of merry mood,

As crumb o’ comfort for her grief,

Methinks her burning lowe’s relief:

Could I, as plays she, play with thee,

That mind might win from misery free!

…

To me t’were grateful (as they say),

Gold codling was to fleet-foot May,

Whose long-bound zone it loosed for aye.

(Catullus, Lesbia’s Sparrow)

Birds appear to have been much more popular a pet in ancient Rome than they are today. In the quote above, we hear from Catullus about Lesbia’s sparrow, or ‘passer’, which she adores.

When it comes to birds, with the length and breadth of the Empire, there was opportunity for an impressive array of species from ducks and geese to ostriches, peacocks, budgies and parrots. In the case of the latter, things get a bit odd when one considers the fact that parrot tongues were something of a delicacy. Again, the contradictory relationship Romans had with their animals.

One popular pastime was, of course, cock fighting. This still goes on in certain parts of the world today, but in ancient Rome, it was also a sport for the upper classes. Plutarch describes how Octavianus always beat Mark Antony at cock fighting:

…we are told that whenever, by way of diversion, lots were cast or dice thrown to decide matters in which they were engaged, Antony came off worsted. They would often match cocks, and often fighting quails, and Caesar’s would always be victorious. (Plutarch, Life of Antony)

I suppose Octavian had to be better at something than Mark Antony, and I imagine that it rankled Marcus Antonius to have Octavianus’ cock beat his own.

Anyway…moving on…

Now we come to the felines of the Empire.

Certainly, exotic big cats were prized in the arenas and menageries, and we have already mentioned Domitian and Caracalla’s pet lions.

But let’s talk about cats as we know them. Today, cats are a very popular pet, but in the world of ancient Rome, they were not so adored as you might expect. Birds and dogs were more popular than cats, though if you walk the streets of Rome or Athens today, you’d think cats had taken over the world.

In ancient Rome, cats served a more utilitarian purpose. They were kept as pets, but it was more for the purpose of catching vermin. There were plenty of mice and rats to go around in Rome, of that we can be sure, though there is mention of another use. The ancient writer Palladius points out that the cattus (Palladius was apparently the first to use the word ‘cattus’) was very good for catching moles in artichoke beds!

I didn’t even know moles liked artichokes.

There was of course one part of the Empire where cats were revered above all other animals, and that was Egypt. Cats were sacred there, and in my research I even read that when cats were smuggled out of Egypt, a ransom was paid to get them back! I wonder if some entrepreneurial Romans ever created a cat-ransom racket to take advantage of the Egyptians’ love of felines?

Of course we cannot discuss animals in the Roman Empire without touching on what was considered a most noble animal – the horse.

Horses were extremely important in the ancient world. Not only were they used as beasts of burden and farm animals, but they were also essential on military campaign as pack animals or in the ranks as auxiliary cavalry.

They were also central to entertainment in the Roman world as chariot racing in the hippodromes of the Empire, like the Circus Maximus in Rome, was the most popular sport around. You can read more about chariot racing HERE. Champion horses were well-treated and even received a pension and luxurious retirement at the end of their careers.

Horses were pets too, and one of the main activities for those in the countryside, rich and poor, was riding for leisure.

Probably one of the most famous instances of a pet horse from the Roman world is Caligula’s horse Incitatus. Suetonius goes into some detail:

He used to send his soldiers on the day before the games and order silence in the neighbourhood, to prevent the horse Incitatusfrom being disturbed. Besides a stall of marble, a manger of ivory, purple blankets and a collar of precious stones, he even gave this horse a house, a troop of slaves and furniture, for the more elegant entertainment of the guests invited in his name; and it is also said that he planned to make him consul. (Suetonius, Life of Caligula)

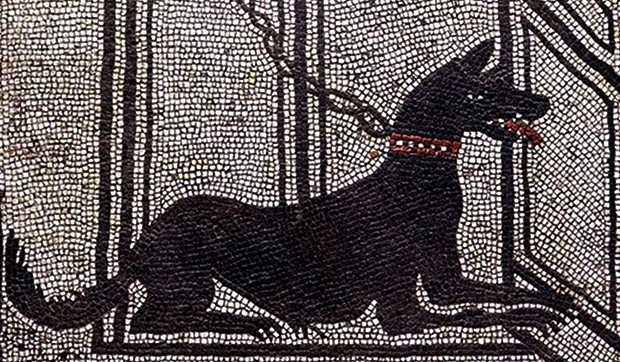

We’ve looked at a few species of animal that were popular among ancient Romans as pets, but none of those mentioned above were more popular as pets in the ancient world than dogs.

As far as pets, dogs were the favourite, and they had an age-old relationship with humans. They were friends, workers, and family members. Dogs were even worthy of serving the gods – think of Diana and her hunting hounds.

The oldest mention of a dog by name is in the Odyssey when there is reference to Odysseus’ dog, Argus.

‘This dog,’ answered Eumaios, ‘belonged to him who has died in a far country. If he were what he was when Odysseus left for Troy, he would soon show you what he could do. There was not a wild beast in the forest that could get away from him when he was once on its tracks. But now he has fallen on evil times, for his master is dead and gone, and the women take no care of him. Servants never do their work when their master’s hand is no longer over them, for Zeus takes half the goodness out of a man when he makes a slave of him.’

So saying he entered the well-built mansion, and made straight for the riotous pretenders in the hall. But Argos passed into the darkness of death, now that he had fulfilled his destiny of faith and seen his master once more after twenty years. (Homer, The Odyssey, Book 17)

There were different breeds for different purposes in ancient Rome. There were dogs for entertainment, fighting in the arena. These dogs were known as canes pugnaces. There were dogs in the Roman army, usually a breed of mastiff, and also for use as guard dogs.

The Roman agriculture writer, Grattius, goes into some detail about various breeds of dogs:

Dogs belong to a thousand lands and they each have characteristics derived from their origin. The Median dog, though undisciplined, is a great fighter, and great glory exalts the far-distant Celtic dogs. Those of the Geloni, on the other hand, shirk a combat and dislike fighting, but they have wise instincts: the Persian is quick in both respects. Some rear Chinese dogs, a breed of unmanageable ferocity; but the Lycaonians, on the other hand, are easy-tempered and big in limb. The Hyrcanian dog, however, is not content with all the energy belonging to his stock: the females of their own will seek unions with wild beasts in the woods: Venus grants them meetings and joins them in the alliance of love. Then the savage paramour wanders safely amid the pens of tame cattle, and the bitch, freely daring to approach the formidable tiger, produces offspring of nobler blood. The whelp, however, has headlong courage: you will find him a‑hunting in the very yard and growing at the expense of much of the cattle’s blood. Still you should rear him: whatever enormities he has placed to his charge at home, he will obliterate them as a mighty combatant on gaining the forest. But that same Umbrian dog which has tracked wild beasts flees from facing them. Would that with his fidelity and shrewdness in scent he could have corresponding courage and corresponding will-power in the conflict! What if you visit the straits of the Morini, tide-swept by a wayward sea, and choose to penetrate even among the Britons? O how great your reward, how great your gain beyond any outlays! If you are not bent on looks and deceptive graces (this is the one defect of the British whelps), at any rate when serious work has come, when bravery must be shown, and the impetuous War-god calls in the utmost hazard, then you could not admire the renowned Molossians so much. (Grattius, Cynegeticon)

Wolfhounds and greyhounds were used for hunting by Romans, and there were even dogs used for religious sacrifice.

Apart from the larger breeds used for the purposes mentioned above, smaller lapdogs were very popular house pets in the Roman world. These were most likely similar to today’s maltese breed of dog.

There are several examples of beloved dogs on grave monuments for family or children that survive. The fact that Romans even did this is testament to the importance placed upon them.

We have but scratched the surface of this vast topic on pets and animals in the Roman world. I hope you’ve found it interesting.

At the end of the day, the wide array of animals that served as pets, workers, food, religious sacrifice and more was as vast and varied a reflection of the world as the Roman Empire itself.

Thank you for reading.

Pompeii – A Brief Introduction with Archaeologist, Raven Todd DaSilva

Hello again, ancient history-lovers!

Way back in the dark days of February, archaeologist Raven Todd DaSilva came to speak to us about gladiators and the famous thumbs-up gesture that we associate with that ancient blood sport. If you missed that, you can check it out HERE.

I’m thrilled to say that Raven is back on the blog with us this week for a brief introduction to one of the great disasters of the Roman world: the destruction of Pompeii.

Raven visited the archaeological site of Pompeii recently and is here to share a bit of the history with us, as well as some new theories around dating, as well as one of her brilliant videos!

So, ready as ever to get digging and get dirty, here’s Raven Todd DaSilva…

Pompeii, a Brief Introduction

By: Raven Todd DaSilva

On an unassuming day in 79 CE, the long-dormant Mount Vesuvius erupted. For three days, volcanic ash and rock rained down on the surrounding area, completely devastating the settlements around it. Most famously- the city of Pompeii.

Founded in the 6th century BCE along the Sarno river, Pompeii originated as a local settlement in Campania. The rich volcanic soil made it favourable for agricultural activity. In the 5th century BCE, the Samnites entered the area, while the 4th century BCE saw the beginning of Roman influence on the region. Pompeii began to flourish under this regime with massive building projects. It became a major port on the Bay of Naples, leading to its “golden age” in the 2nd century BCE. Pompeii was later turned into a seaside resort in 81 BCE. An earthquake damaged many of the buildings in 62 CE, which led to significant economic decline. By the time of the eruption, many of the grand villas built in the 2nd century BCE were converted for public use, leaving the city frozen in time during a period when its glory days were behind it.

Of course, Pompeii gets its fame from the devastating catastrophe because of the rare view it gives us regarding daily life at that time. As the eruption took the city’s inhabitants by surprise, they were not able to properly pack up and evacuate the area, leaving archaeologists with invaluable evidence as to how people really lived in the first century CE.

Not only are we fortunate enough to have the physical site of Pompeii, we also have a primary document describing the eruption of Vesuvius and the immediate aftermath. Pliny the Younger described the events that happened to his uncle, Pliny the Elder, who died assisting refugees onto the warships he was overseeing. This account is also where the infamous quote “Fortune favours the brave” originated. We also have Pliny’s own personal account from Misenum (about 30km away).

The eruption has been described by Pliny the Younger as:

…a pine tree, for it shot up to a great height in the form of a very tall trunk, which spread itself out at the top into a sort of branches; occasioned, I imagine, either by a sudden gust of air that impelled it, the force of which decreased as it advanced upwards, or the cloud itself being pressed back again by its own weight, expanded in the manner I have mentioned; it appeared sometimes bright and sometimes dark and spotted, according as it was either more or less impregnated with earth and cinders.(Letter LXV – To Cornelius Tacitus)

Once the danger of this eruption was realised, people began to evacuate hurriedly, with many people successfully fleeing. Pliny described those escaping as having “pillows tied upon their heads with napkins; and this was their whole defence against the storm of stones that fell around them” (Letter LXV). The stones thrust from the volcano were deadly, crashing through roofs, collapsing buildings and crushing those trying to take refuge under stairs and in cellars. Others, like Pliny the Elder, choked to death on the air as it filled with ash and noxious sulfurous gas. It is believed that 30,000 people died from the eruption.

The traditional date of the eruption is August 24th, as reported by Pliny the Younger, but it has come under scrutiny as further scientific evidence has come to light. Even as early as 1797, the archaeologist Carlo Maria Rosini questioned the date. Rosini reasoned that, as fruits found preserved at the site, such as chestnuts, pomegranates, figs, raisins and pinecones, become ripe in the fall months, they would not have been ripe so early in August. Another study of the distribution of the wind-blown ash at Pompeii supports this theory further. Probably one of the most telling artefacts is a silver coin found that was struck after September 8th, AD 79. As we don’t have an original copy of Pliny’s manuscript, we can assume a typo had been made along the way.

After compiling all this new data, a new eruption date of October 24th, 79 AD has been suggested.

After the eruption, the city remained largely undisturbed until 1738 when Charles of Bourbon, the King of Naples dispatched a team of labourers to hunt for treasures to give to his queen, Maria Amalia Christine, who was enamoured by previously excavated Roman sculptures in the area of Mount Vesuvius. The city of Herculaneum was found first, with Pompeii excavations following it about ten years later.

Today, Pompeii is one of the most popular and well-known archaeological sites, with the longest continual excavation period in the world. With respect to the study of daily life of Rome, it is undeniably important due to the sheer amount of data available. Each year, thousands of visitors flock to Pompeii to walk along the large stone slabs of its roads, visit its iconic brothels, and marvel at the mosaics, wall paintings and body casts preserved by the volcanic ash.

Raven Todd DaSilva is working on her Master’s in art conservation at the University of Amsterdam. Having studied archaeology and ancient history, she started Dig It With Raven to make archaeology, history and conservation exciting and freely accessible to everyone. You can follow all her adventures on Facebook and Instagram @digitwithraven

Resources

Online Articles:

Kris Hirst, What 250 Years of Excavation Have Taught Us About Pompeii https://www.thoughtco.com/pompeii-archaeology-famous-roman-tragedy-167411

Mark Cartwright, Pompeii https://www.ancient.eu/pompeii/

Joshua Hammer, The Fall and Rise and Fall of Pompeii https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/fall-rise-fall-pompeii-180955732/

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Pompeii: Portents of Disaster http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/romans/pompeii_portents_01.shtml

James Owens, Pompeii https://www.nationalgeographic.com/archaeology-and-history/archaeology/pompeii/

Wilhelmina Feemster Jashemski, Pompeii https://www.britannica.com/place/Pompeii

The Two Letters Written by Pliny the Younger about the Eruption of Vesuvius in 70 A.D. – http://www.pompeii.org.uk/s.php/tour-the-two-letters-written-by-pliny-the-elder-about-the-eruption-of-vesuvius-in-79-a-d-history-of-pompeii-en-238-s.htm

Books:

Beard, Mary (2008). Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town. Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-86197-596-6

Butterworth, Alex; Laurence, Ray (2005). Pompeii: The Living City. St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-0-312-35585-2

Kraus, Theodor (1975). Pompeii and Herculaneum: The Living Cities of the Dead. H. N. Abrams. ISBN 9780810904187

As ever, I’d like to thank Raven for another fascinating post and video.

Pompeii is one of those topics that I never tire of, and the exciting thing is that more is being revealed all the time. It’s also one site that I have not yet had the chance to visit, so I really enjoyed learning a bit more.

And I’m definitely looking forward to that next collaboration and video, Raven!

If you haven’t already done so, be sure to check the Dig It with Raven website and subscribe to Raven’s YouTube channel so you can stay up-to-date on all the latest videos about archaeology, history and art conservation.

Cheers, and before you leave, here’s a fantastic time lapse video of Raven’s visit to Pompeii!

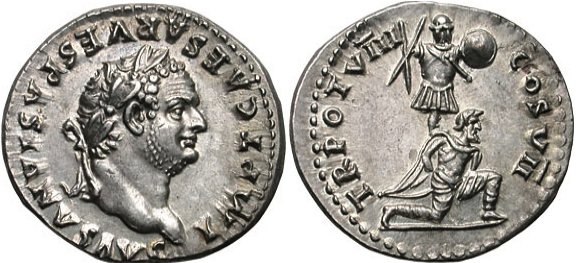

Ancient Everyday – Coinage in Ancient Rome

Greetings ancient history lovers!

It’s been a while since the last Ancient Everyday blog post. If you missed the last one on Roman oil lamps, you can read it HERE.

Today we’re going to take a brief look at coinage in Ancient Rome from it’s inception to the early Imperial period and reforms of Emperor Augustus.

One of the reasons I love writing the Ancient Everyday series is that it shows is how much we actually have in common with the Roman world as far as our daily experiences.

Now, while we might not all have a big cache of loot lying buried in our back gardens, we do use money in some way shape or form on a daily basis.

Romans were no different in that regard, and whether they were getting paid for their legionary service, shopping in the markets of Trajan, or paying for the company of a lovely lupa in the streets of Pompeii, money was exchanged, and that usually in the form of coin.

But coins did not always exist in Rome, indeed not really across most of the early Mediterranean world.

In the ancient world, coins were first produced in the Greek cities of Asia Minor in the late 7th century B.C. These first coins were made of something called ‘electrum’ which was a mixture of gold and silver with simple designs upon them.

Eventually, by about 500 B.C. coin production had spread across the Aegean and to the Greek colonies of southern Italy. These first coins were of pure silver, but the mints of these southern Italian Greeks also produced the first coins made of bronze.

However, before coins were common across Italy, the currency usually came in the form of irregular-shaped lumps of bronze known as aes rude. These were valued by weight.

By the 4th century B.C. bronze was being cast in regular-sized, cast bars, and then by the 3rd century B.C. standard weights were introduced and bars were stamped with images. These were known as aes signatum.

During the Republic, c. 289 B.C., aes grave were introduced. These were pieces of bronze about four inches in diameter that were cast in molds. They superseded the previous, larger bronze bars and became known as an as, or aes, the name given to one of the later denominations of Roman coin.

The as was then divided into smaller values such as a semis (half-as), a triens (a third), a quadrans (a quarter), a sextans (a sixth), and an uncia (a twelfth). These were quite small, but perhaps they would have got you a honeyed pastry in the forum!

As Rome grew in power and wealth, the coinage seemed to follow suit. In the early 3rd century B.C., Roman silver coins began to appear, and these were based on Greek designs coming out of southern Italy. It appears that the first silver coins were struck in Rome itself from about 269 B.C., and the first silver denarii were issued around 211 B.C.

Eventually, silver became the standard for coinage over the previous bronze, and the denarius became the main silver coin of the Roman world.

Other changes were afoot too…

The as was reduced in size so that 1 denarius was equal to 10 asses in the second century B.C. And, around the time of the Second Punic War, gold coins were first issued.

Around 24 B.C. the Emperor Augustus established a standard system of coinage, and under this system, the minting of gold and silver coins was a monopoly of the emperor, and bronze coinage was issued by the Senate of Rome.

Under this new system, four metals were used in coinage: gold, silver, brass, and bronze or copper.

Gold and silver coins were for official uses like salaries, and the baser coins were for everyday uses like market shopping or tipping the attendant at the baths. Augustus knew what he was doing as when a soldier was paid in silver or gold, then the emperor’s face was staring right back at him from that shiny surface. The troops knew who was paying them!

Over time, largely because of increased military spending, the silver denarius, the backbone of the Roman monetary system, became debased until, during the reign of Emperor Severus, a denarius contained only 40-50% silver and the rest was bronze.

But how much were the actual coins worth during the early Empire? Here are the approximate values of the various coins equal to one golden aureus:

You needed 25 silver denarii to equal 1 aureus.

100 brass sestertii were equal to 1 aureus.

You needed 200 brass dupondii for one aureus.

400 bronze asses equaled one golden aureus.

800 brass semis were needed to equal 1 aureus.

And a whopping 1600 bronze quadrans were needed to equal the value of one aureus!

I imagine that the purses of the rich were much easier to carry around than those of the poorer classes in ancient Rome. That’s a lot of bronze to equal just one gold coin!

Of course, in the later Empire, some new denominations came into effect, such as the argenteus, the follis, the solidus, and the centenionalis. Values fluctuated and metals were debased depending on which way the Roman economy veered. Not unlike today, I suppose.

There is one aspect that we should touch on too, and that is the powerful marketing tool coinage was for emperors. Coins were everywhere and in everyone’s hands, and what better way to let the people of the Empire know who was their master and protector than to put your face on the very coins they sought to collect and use to pay for things in their daily lives.

With coinage, the Emperor’s face was with you at all times, reminding you who was in charge. Coins gave you their likeness and also helped to commemorate victories over Rome’s enemies.

One thing is for sure…

In the world of Imperial Rome, for better or worse, money was one of the things that made the wheels of the Empire turn, and coin passed through the hands of rich and poor alike. Only some had more of it than others.

Thank you for reading.

Chariot Racing in Ancient Rome

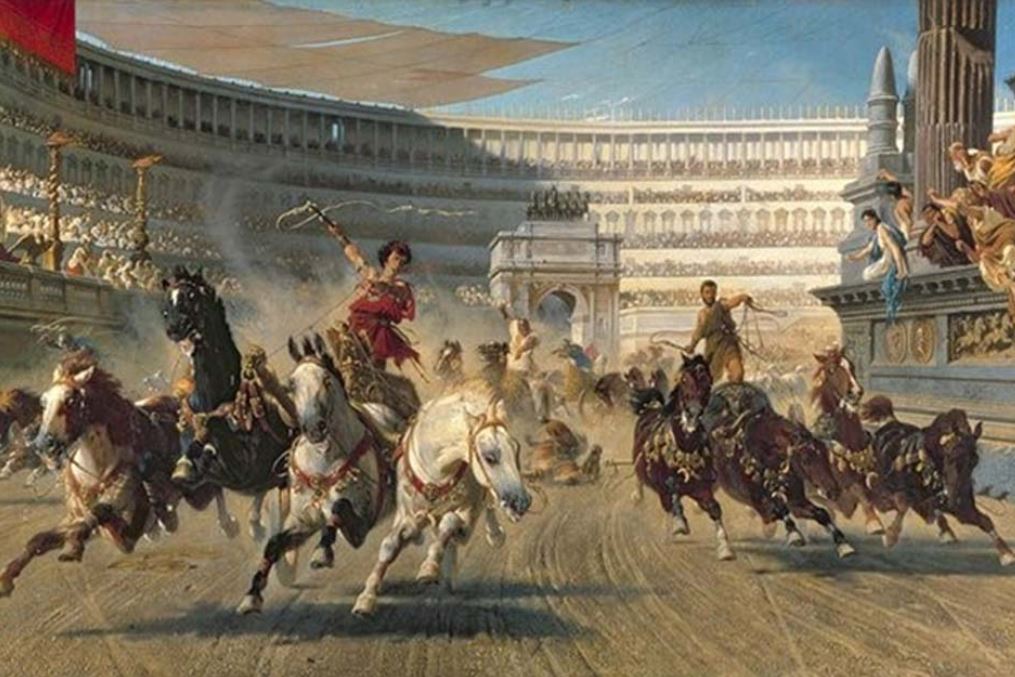

See you not, when in headlong contest the chariots have seized upon the plain, and stream in a torrent from the barrier, when the young drivers’ hopes are high, and throbbing fear drains each bounding heart? On they press with circling lash, bending forward to slacken rein; fiercely flies the glowing wheel. Now sinking low, now raised aloft, they seem to be borne through empty air and to soar skyward. No rest, not stay is there; but a cloud of yellow sand mounts aloft, and they are wet with the foam and the breath of those in pursuit: so strong is their love of renown, so dear is triumph. (Virgil, Georgics III-IV)

When we think of the raucous world of sport in ancient Rome, the images we conjure are most often of blood-soaked gladiatorial combat, or of chariot racing.

Today, we might think that gladiatorial combat was the most popular sport amongst the people of Rome, but in truth, nothing was more sensational than the chariot races put on in the great circus of Rome – the Circus Maximus.

In this post, we’re going to take a brief look at the circus itself, the charioteers, the horses, the fans, equipment, and what teams stood to win…and lose.

Their temple, dwelling, meeting-place, in fact the centre of all their hopes and desires, is the Circus Maximus. (Ammianus Marcellinus on Plebs and the Circus, XXVIII.4)

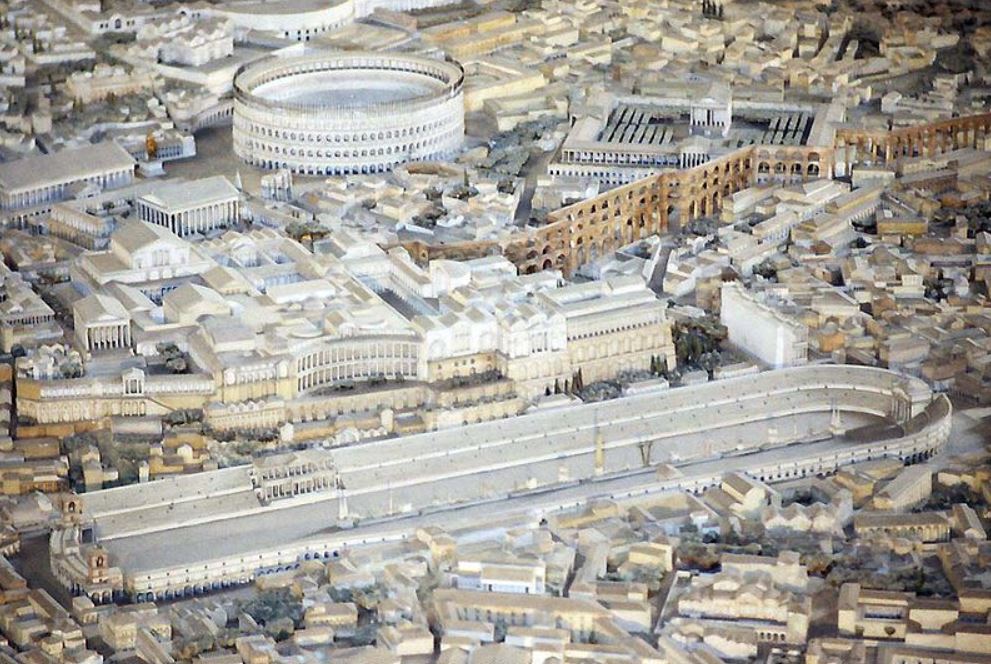

Chariot racing was an ancient sport handed down from the Greeks to the Etruscans and Romans early in the history of Rome, the races in the city of Rome being held in a dip in the land between the Palatine and Aventine Hills. Over time, the Circus Maximus was built upon by successive senates and emperors, making it the largest in the Roman world.

Rome’s great circus had an area of 45,000 square meters, making it twelve times larger than the Colosseum, and it could hold at least 150,000 spectators. With the addition of temporary wooden seating, the capacity was said to have reached 250,000!

The Circus Maximus was the largest and most expensive entertainment venue in Rome. Buildings had been added to it from the fourth century B.C. onward, going from wood to stone, and a major renovation was done in the first century B.C. Before the Colosseum was built, the Circus Maximus also hosted gladiatorial combats, wild animal hunts, and other games.

The Circus Maximus certainly owns its name, for by the time of Emperor Trajan, it was about 550-580 meters long, and about 80-125 meters wide. At the start of the track, there were twelve carceres, starting boxes, with ostia (gates) from which the teams would shoot out and charge the first 170 meters toward the central spina, which divided the course and which is what the teams raced around. The spina was 335 meters in length and 8 meters wide, and at each end of it were metae, the turning posts which the riders sped around. The spina was also ornamented with statues of the gods, towering palms, and obelisks from Rome’s campaigns in Egypt.

There were also large frames on the spina with mechanisms with suspended dolphins and eggs to count down the laps for a race. The total distance of a race of seven laps was about 5,200 meters over the packed earth and gravel track.

When it came to putting on games, or ludi as they were known, in the Circus Maximus, hundreds of staff were required in addition to the aurigae, the charioteers themselves. There were stable boys, grooms, cartwrights, saddlers, doctors, veterinarians, men at each of the starting gates (which were each six meters wide in Rome), men to clear the debris after crashes, lap counters, musicians, and even performers between races usually comprised of riders or acrobats.

That’s a lot of people to keep things running, but it was worth it to those who put on the games, for the people of Rome loved their chariot teams.

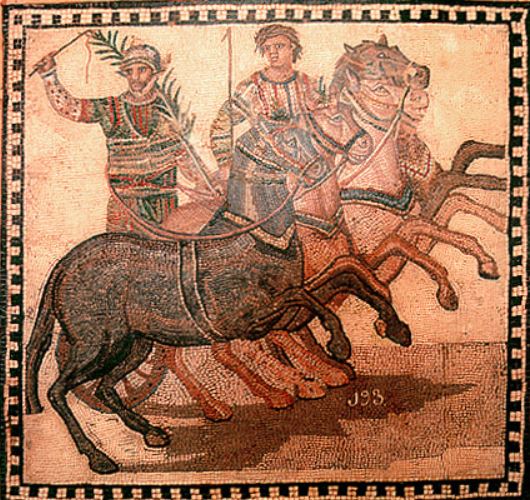

One might think that fans usually cheered for their favourite charioteers, but in truth, Romans were fans of their favourite factions, or factiones as they were known. There were four chariot factions in Rome: the Veneti (Blues), the Prasini (Greens), the Russati (Reds) and the Albati (Whites).

The four chariot factions of Rome were managed by the domini factionis, the ‘faction masters’ who were usually men of the Equestrian class. They would have sought out potential charioteers, made deals with others, and generally seen to the running of the faction and its success. The domini factionis were similar to the lanista of a gladiatorial school, or ludus.

In Rome, the factions had their headquarters, the stabula factionum, which contained accommodation and stables, on the Campus Martius, but their breeding grounds and training camps were located in the countryside.

People were wild for their factions, and there could be violence between the followers of each. During a race, each faction could enter either one, two, or three separate teams so that a full race could comprise up to twelve chariot teams running at a single time.

But who were the men who drove the factions to victory or defeat? Who were the charioteers of Rome?

O Rome, I am Scorpus, the glory of your noisy circus, the object of your applause, your short-lived favourite. The envious Lachesis, when she cut me off in my twenty-seventh year, accounted me, in judging by the number of my victories, to be an old man.

(Martial, Epigrammata, LIII. Epitaph of the charioteer Scorpus)

Outside of Rome, in the hippodromes of distant provinces, it was possible for individual owners to enter teams or even race themselves, but in Rome’s circus, it was the factions who entered the teams, and the professional charioteers, the aurigae, who raced for each faction.

The aurigae were usually slaves or freedmen, low on the status scale the same as gladiators, but they could achieve great fame and wealth.

In his Epigrammata, the poet Martial tells us of a famed auriga named Scorpus who was one of the few charioteers to achieve the status of miliarius. The miliarii were those who had won over one thousand races – Scorpus was said to have won 2,048!

Ancient chariot racing in Rome was not dissimilar to modern sports. People were loyal to their faction, their ‘team’ so to speak, and charioteers, like pro sports players today, might be traded to or wooed by other factions. It was not uncommon for a charioteer to move factions several times before settling down in the latter half of his career.

Servants’ hands hold mouth and reins and with knotted cords force the twisted manes to hide themselves, and all the while they incite the steeds, eagerly cheering them with encouraging pats and instilling a rapturous frenzy. There behind the barriers chafe those beasts, pressing against the fastenings, while a vapoury blast comes forth between the wooden bars and even before the race the field they have not yet entered is filled with their panting breath. They push, they bustle, they drag, they struggle, they rage, they jump, they fear and are feared; never are their feet still, but restlessly they lash the hardened timber.

At last the herald with loud blare of trumpet calls forth the impatient teams and launches the fleet chariots into the field. (Sidonius Apollinaris, To Consentius)

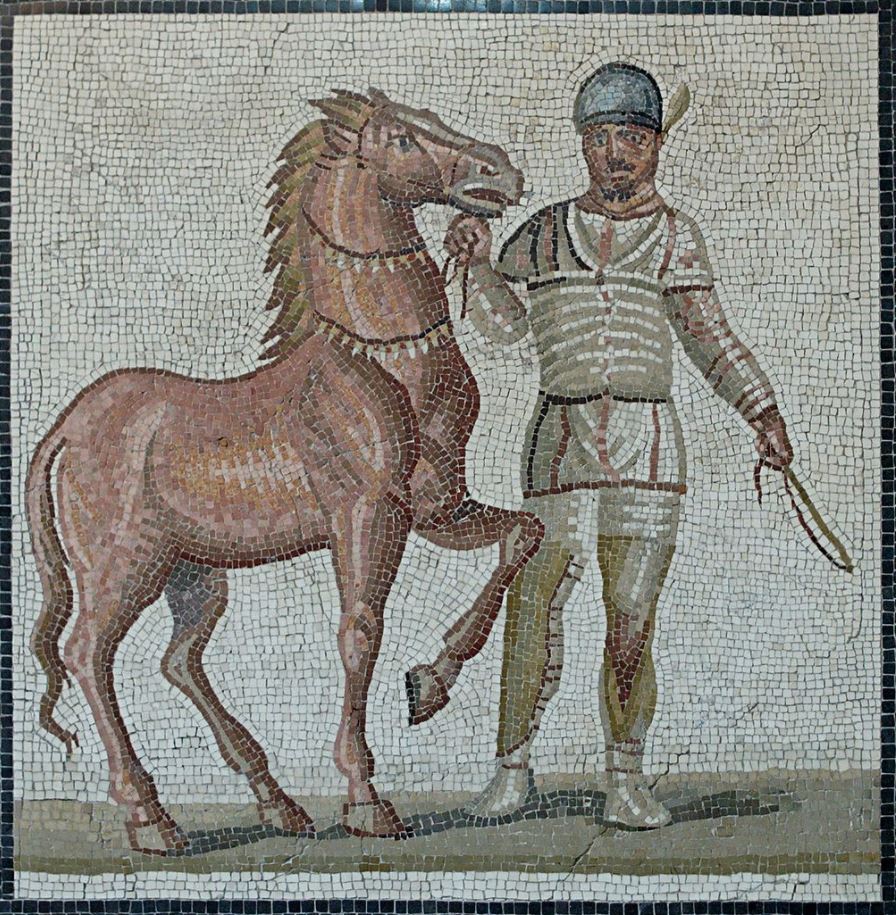

It wasn’t just the aurigae who achieved fame in the Circus Maximus. Horses too could be just as famous as their drivers, and oftentimes equine heroes were met with adoration.

Winning horses received palm branches, but also modii, which were measures of grain, with barley thrown into the mix. They were no doubt pampered back at the stabula factionum, and those horses who ran their factions to victory after victory enjoyed retirement in the countryside on a pension. They even received a burial with honour.

Race horses were bred and trained on private, and later imperial, stud farms, and the most successful breeds to race in the Circus Maximus were Lusitanos and Andalusian breeds from North Africa and Spain.

Though the horses were well-cared for by the factions, the racing was hard on their joints because of the tight turns of almost 180 degrees around the metae, and of course the great risk of injury.

Animal losses were high in the circus of Rome.

When it comes to the chariots and equipment used for the sport of chariot racing in ancient Rome, the movies have often been misleading.

In movies like Ben Hur (pictured above) the chariots are massive, some with long blades sticking out of the wheels. The chariots used in the movie made for some exciting film making and a great scene, but they were not at all accurate as far as what was really used.

Statue of a Roman biga (two-horse chariot) found in the Tiber. Note how much smaller the chariots actually were compared to what we see in the movies

Roman racing chariots, which were adapted from the ancient Greek and Etruscan chariots, were light-weight affairs, consisting of a slight wooden frame bound with strips of leather or linen, and small wheels with 6-8 spokes.

The most common chariot was the quadriga, a four-horse chariot from ancient Greece. The other commonly-used chariot was the biga, a Roman two-horse chariot. These two types were what were raced most often in the Circus Maximus in Rome. However, there were said to have been six-horse chariots (seiugae), eight-horse chariots (octoviugae), and even a ten-horse chariot (decemiugae).

Unfortunately, no remains of an imperial Roman chariot have been found, so we are forced to rely on artwork for an idea of their appearance. However, the tombs of Etruscan nobility have yielded some two-hundred and fifty examples of chariots.

In ancient Greece, charioteers wore only a long chiton with a belt when they raced, but Roman and Etruscan aurigae wore a short chiton, a protective skull cap or leather helm, and a wide leather belt composed of many straps. They also wore linen or leather wrappings on their legs and carried a curved dagger on them.

Why did they carry a dagger?

Well, it wasn’t to attack each other during the races. The reason for the dagger was that unlike Greek charioteers who held the reins in their hands, Roman charioteers wrapped the reins around their waists in order to use their whole body to steer the team and have one hand completely free for the whip.

If they ever got into a naufragia, a ‘shipwreck’ as chariot accidents were called, the dagger was supposed to be used to cut oneself free of the reins that were wrapped about you. It certainly was a risk when driving a team of four horses up to 75 kms per hour while trying to cut off your opponents going into the turns and so on.

One thing’s for sure, Roman chariot racing was extremely dangerous, though perhaps not as hazardous to one’s life as gladiatorial combat.

Games, or ludi, were the highlight of the Roman calendar, and chariot racing in the Circus Maximus was always the main event. During imperial games, there were usually up to twenty-four races per day at Rome, and that could include up to 1,152 horses.

This was always an event on a titanic scale, and the people of Rome loved it!

People were fanatical about their factions, and the charioteers who risked their lives in the Circus Maximus must have felt near to gods when the adoration of the crowd shone full upon their faces.

Apart from the traditional victory palm, winning charioteers and their factions could receive massive fortunes for their success.

In Rome, prizes ranged from 15,000 to 60,000 sestercii per race! That’s far more than the annual pay for a legionary soldier who received about 900 sestercii per year during the early Empire.

One charioteer by the name of Gaius Appuleius Diocles was said to have won almost 1,500 races and when he retired at the age of forty-two, he had a fortune of 35.5 million sestercii!

I guess some things don’t change, as the salary of military personnel today is far outstripped by that of the average sports star.