Salvete readers and Romanophiles!

This week on Writing the Past, I’d like to welcome fellow author, A. David Singh, who has written a fantastic piece for us about slavery in ancient Rome.

You probably know that slavery was widespread in the Roman world, but what you might not know are the ins and outs of slaves’ lives.

Check out David’s post below for a brilliant introduction to this topic…

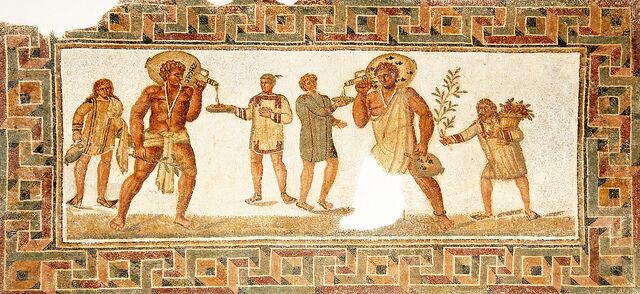

Slaves serving at a banquet – mosaic floor. Found in Dougga, Tunisia, 3rd century A.D. (Dennis Jarvis_Flickr)

In the first century A.D., over a million people lived in Rome — and a third of them were slaves.

Ancient Romans considered their households to be a microcosm of the state of Rome, and slaves were an integral part of their households. Slavery was such a key foundation of their society that if an ancient Roman were to time-travel to the present day, he would be surprised to see a society function just fine without slaves.

In addition to cooking, cleaning, and carrying loads within their master’s household or country estate, slaves served another important function — that of elevating the social status of their masters. This is much the same prestige that a champion race-horse confers upon its owner.

How did one become a slave?

Being born into slavery was the commonest way. Children born to a women slave automatically became slaves to her master.

Another way was by capturing enemies. As Rome waged wars far beyond its borders — in Europe, Asia and northern Africa — a steady supply of prisoners of war poured in, who, in lieu of their lives being spared, were sold to the slave-traders. During his Gallic campaigns, Julius Caesar is rumored to have captured over a million prisoners of war in Gaul and sold them into slavery.

Criminals too could be enslaved, but their masters had to be careful about their violent streak. Unwanted babies who were thrown into rubbish dumps outside the city, though technically free, could be picked up by slave dealers or surrogate parents who would sell them into slavery. A similar fate awaited children kidnapped by pirates and other shady elements of society.

Finally, free Roman citizens, if deep in debt, could be forced into slavery. Some of them voluntarily chose to become slaves to repay their debt. However, Roman citizens submitting to slavery was considered illegal.

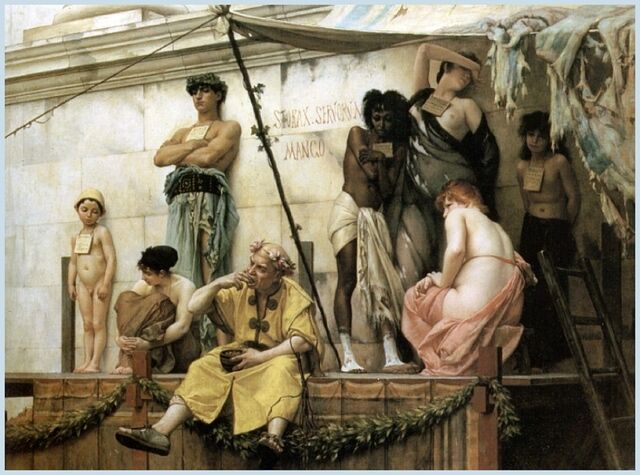

Where were slaves sold in Rome?

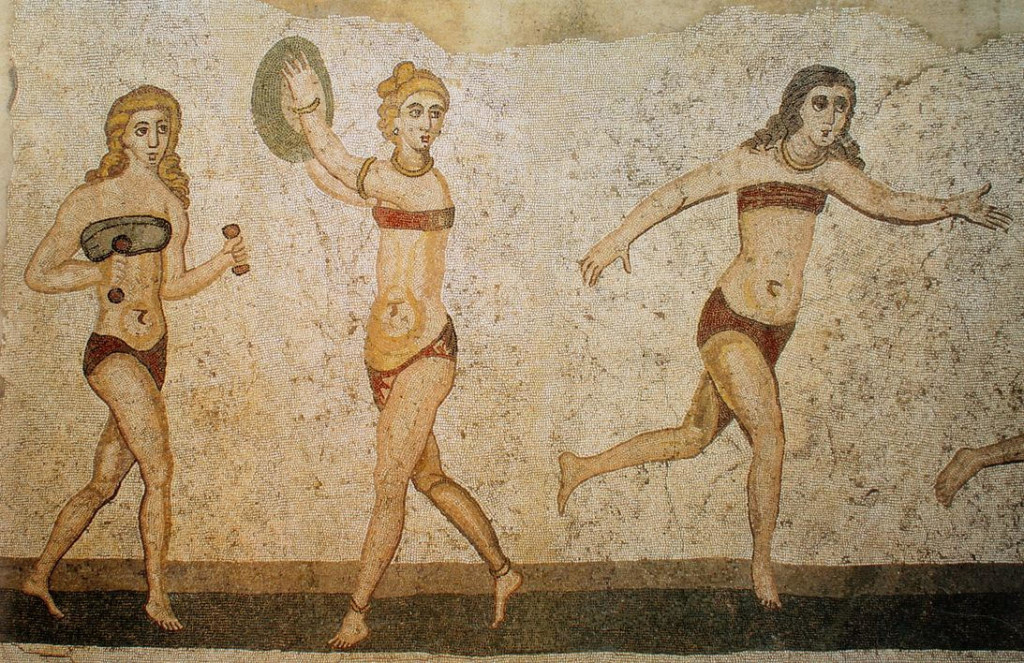

The slave market was commonly held behind the temple of Castor and Pollux, and also near the Pantheon. Men, women and children were displayed on raised platforms, just like fruit stands in a bazaar. They wore dejected looks, being resigned to their fates.

The slave trader adorned them with signboards around their necks with information like place of birth and other personal characteristics. It was a common spectacle to see signs like: Gaul, cook, specializes in making spicy fish and the use of Garum or Greek, ideal for teaching philosophy and reciting verses during parties.

Those who came to buy slaves found it in their interest to ensure that the slaves had no physical or mental defects. So, a thorough examination of their bodies was a common occurrence, and putting them on raised platforms helped to do just that.

A young male, 15 to 40 years old, cost 1,000 sesterces, while a female was priced at 800 sesterces. Much younger slaves or those older than 40 years went cheaper. Of course, prices would have been higher for slaves with special skills like reading and accounting.

The slave market had different days allocated for selling different types of slaves. There was a day for selling strong, muscular slaves meant for heavy labor. Another day for those specializing in trades like bakers, dancers and cooks. Boys and girls meant to work in houses and for banquets had their own day of sale, as did those with physical deformities.

What happened afterwards?

Once they started their lives of servitude, not all slaves had the same luck. The best deal that a slave could hope for was becoming a house slave to a kind master — even better, if the master was an important man in Rome. Moreover, there was also the possibility of being freed one day.

Then there was a class of slaves who worked in shops, under the command of an ex-slave. In addition to lugging heavy loads, they had to contend with the emotional baggage of their boss’ recently concluded life as a slave.

Those less fortunate were sold into miserable hovels of brothels, used pitilessly till they broke down or became useless. But a worse fate awaited those slaves who worked in country estates and mines. They lived in pathetic conditions with little food, frequent beatings, and were even locked in filthy prisons at night. It’s no wonder that they had very short life expectancies.

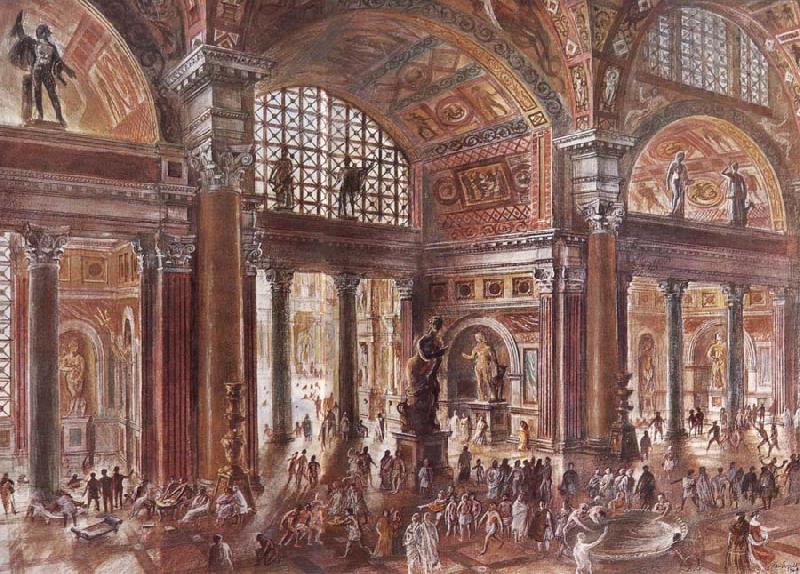

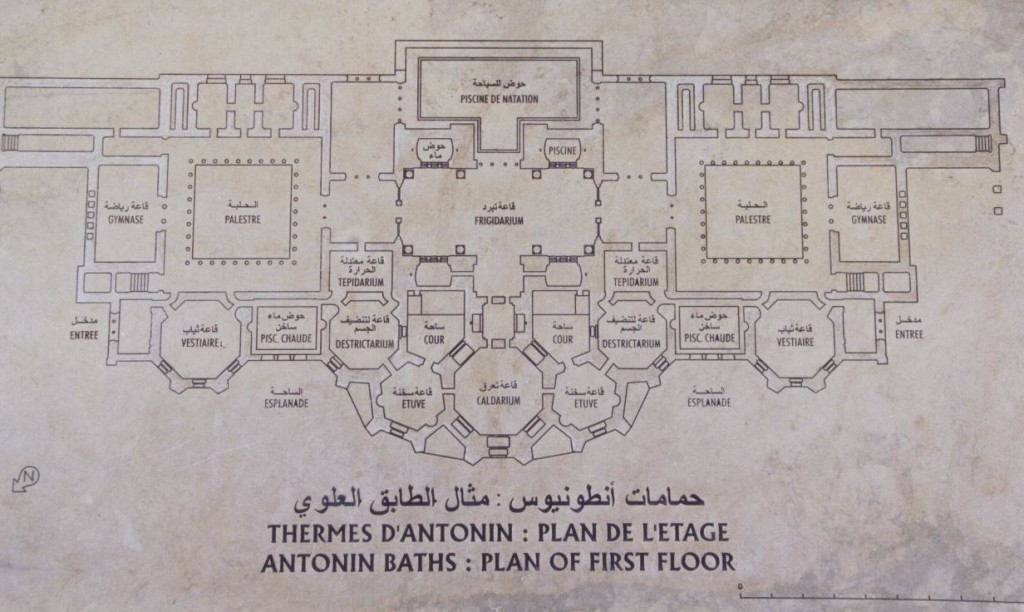

Wealthy Romans were not the only people to own slaves. The state of Rome had its own collection. These slaves were of another class — public slaves. They worked in public baths, food warehouses, or constructed roads and bridges, or worked in public administration offices. They helped in running the economy of Rome. Life was probably kinder to them than to their counterparts who worked in the mines and country estates.

The conditions for slaves were extreme during the Roman Republic. But it is believed that they eased later on. During the Empire, slaves could earn money, get married (informally) and have children. Killing of slaves was banned.

The Slave Market – oil painting by Gustave Boulanger, 1886 (Wikimedia Commons)

What were master-slave relationships like?

In rigid households, slaves were considered nothing more than objects that could talk and walk. They could be sold, rented, or replaced, just the way we do nowadays to our inanimate possessions. The master always decided the level of relationship permitted to their slaves. They could be friendly, or exploit their slaves, or in extreme circumstances even kill them.

On the other hand, if a slave killed his master, then all the other slaves in the household were slaughtered under the charge that they failed to protect their master from the rogue slave.

However, many masters considered slaves as human beings, worthy of moral behavior, and hence treated them with a degree of respect.

Each master had to balance how he treated slaves with the need to keep them working. Brutal treatments were rare because they would wear out the slaves.

Home-born slaves were most likely to remain loyal to their masters, considering him like their own father (which, in many cases he really was). However, barbarians captured from distant lands took some time to be broken into their new, reduced station in life.

Most often, masters incentivized slaves to work hard and stay loyal. Firstly, they rewarded hard work with generous rations of food and clothing. At times, even allowing them to have children, and occasionally organized sacrifices and holidays for them. Such acts of generosity went a long way in ensuring their slaves’ loyalty.

Secondly, slaves had clearly defined job roles, suitable to the their mental and physical attributes, like cooks, door-keepers, or food-servers. This division of labor generated accountability, as the slaves knew that they could be punished only for jobs that they were responsible for, and not for duties outside their job descriptions.

But the most important incentive for slaves to work honestly and with diligence was the possibility of gaining their freedom and becoming Roman citizens.

Manumission

Unlike the Greeks, the Romans took a liberal view of slavery, regularly incorporating slaves into their own society. Thus slavery was viewed as a temporary state, after which, if the slave had shown the right attitude, they could be set free and become a Roman citizen.

This process of leaving the shackles of slavery and becoming free men and women was called ‘manumission’.

If a master was happy with a slave’s services and felt him worthy of being free, the slave could be set free by appearing before a magistrate. Once the magistrate had confirmed that the slave was a free man, the master would often slap the slave, as a final insult, before he started his new life.

Often, a master would bequeath his slaves’ freedom in his will. This is how most slaves got their freedom. In rare cases, slaves could also buy their freedom, if they could raise enough coin — or get another freedman to buy their freedom.

Manumission was generally practiced in urban regions, where it was possible for slaves to form meaningful relationships with their masters and be in their good books. Those working in country estates or mines did not have direct contact with their masters, and were usually worked to death.

Relief showing manumission of a slave. Marble, 1st century B.C. Musèe Royal de Mariemont (Ad Meskens_Wikimedia Commons)