Welcome back to The World of An Altar of Indignities, the blog series in which we share the research for our latest novel, An Altar of Indignities: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome and Athens.

If you missed the second post on travel and transportation in the Roman Empire, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In part three of this blog series, we’re going to be looking at some of the Roman monuments and additions to the great city of Athens that appear in the novel.

Let’s get started!

Pericles’ funeral oration for the dead of the Peloponnesian War in the Kerameikos of Athens by Philipp Foltz (1852)

When we think of Athens today, we inevitably think of that ‘Golden Age’ city which Pericles, after the destruction wrought by the war with Persia, helped to build into a beacon of light and learning for the world.

There is the ancient Agora with its restored stoa of Attalus, one of a few such structures, myriad statue bases and altars. There is, of course, the beautiful temple of Hephaestus overlooking the Agora where other temples of Ares, Apollo, and Aphrodite were located. This vast area was the beating heart of ‘Golden Age’ Athens.

There is the Kerameikos district about the great Dipylon Gate of Athens’ ancient walls where the road to Eleusis leads through the cemetery where Pericles gave his famous funeral oration honouring the dead of the Peloponnesian war.

On the south side of the Acropolis, there is the Pnyx where the citizens of Athens met to participate in the new experiment known as ‘Democracy’, as well as the magnificent theatre of Dionysus where the first dramas in history were performed, and the Odeon of Pericles beside the theatre where musical and poetry performances entranced Athenian audiences.

Painting of ‘Golden Age’ Athens by Leo von Klenze (1846)

Above all of these monuments and more was the temple of Athena Parthenos, the Parthenon, the crowning achievement of ancient Athens that hovered like Olympus above the city.

The remains of the ‘Golden Age’ of ancient Athens are everywhere, and history lovers flock to it as much today as they did in ages past.

However… Our story takes place in Roman Athens in the early third century C.E. What did Athens look like long after the setting of the city’s ‘Golden Age’? What did the Romans ever do for Athens?

The answer is, quite a lot.

Sadly, unlike many of Rome’s relationships, it started off with the usual violence that preceded the productive calm and beauty of the Pax Romana.

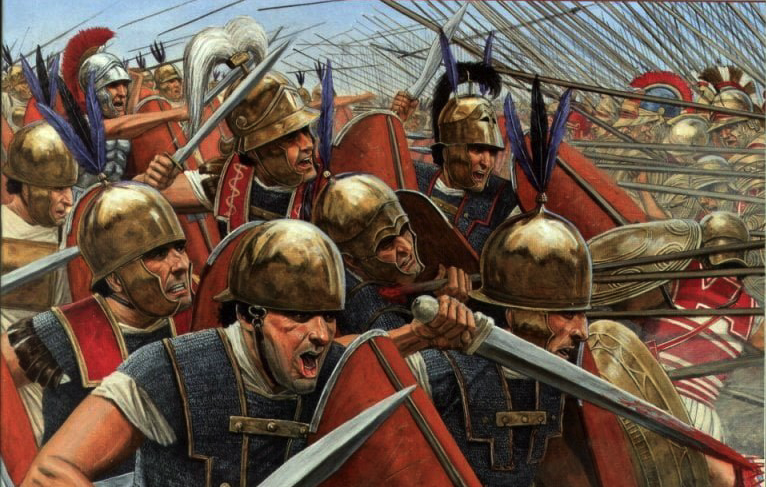

The Roman occupation of Greece really began in 146 B.C.E with the defeat and total destruction of the city of Corinth by Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus who arrived from the north, and then Consul Lucius Mummius.

Then, in 88 B.C.E when Athens and other cities revolted against Roman occupation, Lucius Cornelius Sulla devastated Greece. Athens suffered greatly at the hands of Sulla and much of that ‘Golden Age’ city was destroyed or damaged during his siege of the Acropolis.

Subsequently, Athens and the rest of Greece were to remain a part of the Roman Empire after the battle of Actium in 31 B.C.E when Octavian (later Emperor Augustus) crushed the forces of Mark Antony and Queen Cleopatra thus heralding the end of the Hellenistic Age and beginning the long period of Roman hegemony over the Mediterranean.

Emperor Augustus

After all the destruction, however, under Roman rule Athens began to experience a revival with several rulers really enriching the city for all that it had contributed. You see, many Romans, especially educated ones, really admired Athens and its legacy, a legacy from which Rome had adopted a great deal.

Under Roman rule, Athens saw the construction of several Roman monuments that still stand to this day, at least partially. We are going to take a brief look at a few of them.

Not only were improvements and repairs made to existing monuments, but completely new ones were added to his ancient city, including several public bath houses that were erected in various places.

Vintage engraving of the Theatre of Dionysus with the Roman scaena frons

Among the existing monuments that were repaired and updated was the ancient theatre of Dionysus where the great theatre festivals, such as the Dionysia, took place. At various stages over the Roman period, the theatre was renovated and expanded with more seating and a large scaena frons, or stagehouse.

Fifteen years or so after the Battle of Actium, a new odeon was built around 15 B.C.E in the middle of the Ancient Agora by the general, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. This covered, two-storey structure could seat about one thousand people and is still visible today by the carved tritons on its north side.

Recreation of the exterior and interior of the Odeon of Agrippa in the ancient Agora of Athens

One of the most important additions made by Rome to the city of Athens was the Roman Agora or ‘Roman Forum’ built between 19-11 B.C.E by Augustus in fulfillment of a promise to the city by Julius Caesar.

This ‘new’ agora features largely in An Altar of Indignities, and is the site of a particularly riotous scene!

While the original ancient Agora of Athens remained an important focus of the city, it had become crowded with stoas, temples, and monuments to heroes and to the gods. There were fountains, a library, a mint, offices, altars, sanctuaries and more. But the first agora came to lack the great open space that allowed people to gather and trade with ease. The new, Roman Agora allowed for this.

Aerial photo of the Roman Agora of Athens with the gate of Athena Archegetis in the foreground

The Roman Agora of Athens consisted of a large paved, open-air courtyard that was surrounded by colonnades of white and grey marble from the surrounding mountains of Penteli and Hymettos. The colonnades were covered and had spaces for shops and merchants selling various goods, storerooms, the offices of the market, and a fountain. There was also an adjacent public latrine.

There were two propylaea, including the Gate of Athena Archegetis at the west end, and another propylon at the east end. Both entrances aligned with the ancient roads at either side.

The Tower of the Winds – the oldest meteorological station in the world

Just outside the eastern wall of the Roman Agora is a fascinating and unique Roman-era structure known as the Tower of the Winds.

The Tower of the Winds, built by Andronicus in the first century B.C.E, is said to be the oldest meteorological station in the world with sundials on the exterior, a hydraulic clock inside, and its bronze weather vane on top indicating the eight winds which is thought to have allowed merchants in the agora to know the winds and estimate the arrival of shipments coming from the port of Piraeus.

CLICK HERE to read our article on the Roman Agora of Athens and watch our full video tour of the archaeological site.

Emperor Hadrian (gold aureus)

There is one Roman ruler who looms very large in the history of Athens and that is Emperor Hadrian. Everywhere you go in the historic centre of the city, you are reminded of Hadrian. He loved Athens, and he loved to make things on an especially grand scale. Much of what he built in Athens is still visible today.

Beyond the walls of the Roman Agora are the remains of the great library built by Hadrian. Hadrian’s Library, as it is known, was built in 132 C.E. It was a large complex that served not only as a library, but also a cultural centre and public space that included lecture halls, a reading room, a vast courtyard and garden with a pool and, of course, the enormous bibliostasion where myriad precious scrolls were kept.

Today, you can visit the library by away of the monumental entrance near Monastiraki square, roam the gardens where mosaics are still open to the sky, and see the remaining walls of this magnificent piece off Athens’ cultural past.

The ‘Bibliostasion’ of the Library of Hadrian in Plaka, Athens

Southeast of the Acropolis are two more monuments to Hadrian’s generosity and love of grandeur. The one is the Arch of Hadrian which was built around 132 C.E. to honour the emperor. This gate, which one can walk up to today, marked the boundary between the ancient city of Athens and the new district built by Hadrian sometimes known as ‘Novae Athenae’ or ‘New Athens’.

Hadrian’s Gate

Just beyond the Arch of Hadrian, is perhaps one of the most impressive achievements of that emperor: the Temple of Olympian Zeus.

The Temple of Olympian Zeus, or the ‘Olympieion’ as it is known, was one of the largest temples ever built in the ancient world. Construction on it was begun as far back as the sixth century B.C.E under Peisistratos, but it was so ambitious that it was never finished.

Until Emperor Hadrian.

In 131 C.E., after over six hundred years, Emperor Hadrian finally completed the great Olympieion of Athens. The temple had a forest of 104 massive Corinthian columns and contained one of the largest cult statues of the ancient world.

The Temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens, as seen from the Acropolis

Today, only 15 of those magnificent columns remain standing. Nevertheless, this is a wonderful site to visit and the remains still give one a sense of the scale of this marvel of ancient architecture and great love that Emperor Hadrian had for Athens.

There is another Roman who features almost as largely as Hadrian in Athens’ past, and that is the wealthy Roman senator, Herodes Atticus. We will look at the man himself in a separate post in this series, but for now we will go over a few of the monuments he contributed to this ancient city.

The Panathenaic Stadium

The Panathenaic Stadium, or Kallimarmaro ( meaning ‘nice marble’), is one of the most recognizable monuments from ancient Athens, and it is still used to this day. It was originally built by Lycurgus in the fourth century B.C.E for the Panathenaea and is located in the small valley between the hills of Agras and Ardittos at the foot of the neighbourhood of Pangrati.

However, it was in about 144 C.E. that Herodes Atticus rebuilt the stadium in marble, after which it had a capacity of 50,000. This same stadium was excavated and restored in 1896 to host the first modern Olympic Games and is still used today for various Olympic ceremonies.

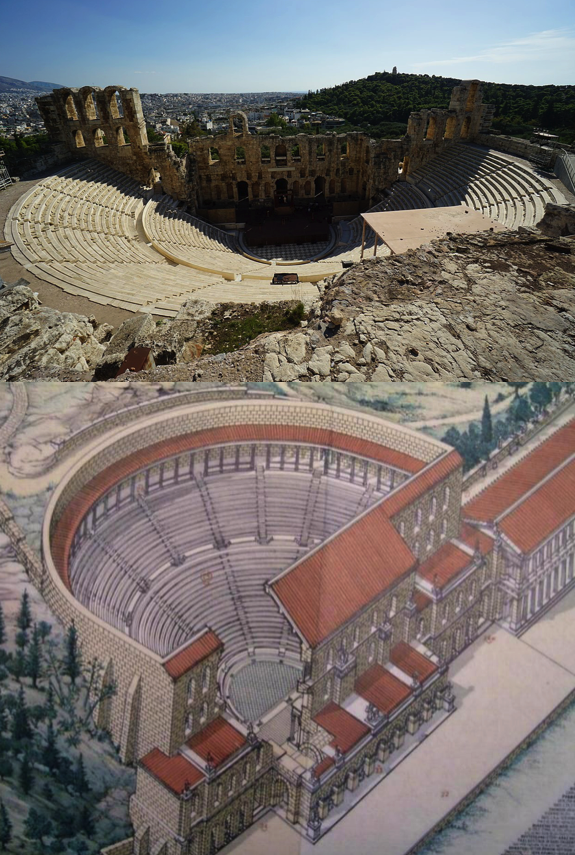

The Roman-era Odeon of Herodes Atticus, Athens

The monument for which Herodes Atticus is most famous in Athens is the one that bears his name: the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, or ‘The Herodeion’.

We will also take a close look at this amazing monument in a separate post in this blog series as it is central to the story of An Altar of Indignities. For now, the Odeon of Herodes Atticus was built around 161 C.E on the south slope of the Acropolis. It was a roofed odeon and served as a venue for concerts, theatrical performances and other public events. It remains in use to this day as a part of the annual Athens Epidaurus Festival, along with the great theatre of Epidaurus in the Peloponnese.

Philopappos Monument on the Hill of the Muses (Wikimedia Commons)

On the nearby Hill of the Muses, across the modern street from the Acropolis is another monument from the Roman period. It is known as the ‘Monument of Philopappos’. It was erected in around 114-116 C.E in honour of a Roman consul of Greek descent, Gaius Julius Antiochus Epiphanes Philopappos.

This grand monument that seems to jut out of the trees on the Hill of the Muses served as a mausoleum to this Roman-Greek consul, and is an indication of his importance to Athenian society at the time. Philopappos was said to have also been a poet and personal friend of Emperor Hadrian and Empress Vibia Sabina, making this yet another magnificent addition to the Hadrianic-period legacy of the city.

The Acropolis of Athens

When it comes to Athens, however, there is no monument greater, or more recognizable, than the Acropolis. This ‘high city’, crowned by the Temple of Athena Parthenos (the Parthenon) and other buildings and temples such as the Propylaea, the Erectheion, the Temple of Athena Nike, and the sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia, are all glorious reminders of Athens’ Archaic and Golden ages.

When it comes to the Roman period, much restoration of existing monuments was undertaken as structures had been damaged by time and war, not least Sulla’s siege of the Acropolis.

There were some monuments with statues that had been erected by foreign kings such as Attalos II of Pergamon (at the northwest corner of the Parthenon) and by Eumenes II in front of the Propylaea, the monumental entrance to the Acropolis plateau. These Hellenistic structures were later rededicated by Emperor Augustus and General Agrippa.

Recreation and present state of theT emple of Rome and Augustus on the Acropolis (Wikimedia Commons)

The only new, Roman addition to the Acropolis was that of the circular Temple of Rome and Augustus which was located about twenty-three meters from the Parthenon on the east side. This was constructed around 19 B.C.E to honour Rome and Emperor Augustus and was the last great construction to take place on the summit. This temple did not have a cella, as most temples did, but was more of an open air tholos (round temple) with a statue of Augustus beneath a roof supported by nine Ionic columns. Later, a metallic inscription was added to the temple to honour Emperor Nero, but this was later removed.

For a series of wonderful 3D recreations of Roman Athens, we highly recommend you visit the website for AncientAthens3D HERE.

Modern aerial view of the three harbours of the port of Piraeus, the port of Athens. The smaller harbours in the foreground are the ancient military harbours of Zea and Munichia. The commercial harbour of Kantharos is in the background.

Lastly, we cannot have a discussion of Roman monuments of Athens without mentioning the great port of Athens: Piraeus.

The port of Piraeus was made up of three harbours: the great commercial harbour of Kantharos (featured in An Altar of Indignities), and the smaller military harbours of Zea and Munichia.

Piraeus has been an important naval and commercial hub for centuries and, in the Classical Greek and Roman periods, it was vital. When Greece came under Roman rule, much was done to improve the port of Piraeus as the Romans relied heavily upon it.

Infrastructure, such as docking facilities, warehouses and the road to Athens, were repaired, improved and expanded. This was for efficiency, but also to accommodate the larger Roman ships. The Romans are also believed to have improved the fortifications of Piraeus.

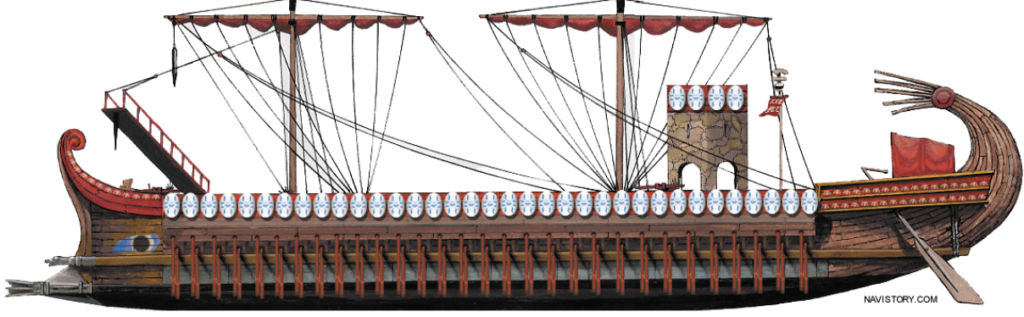

Recreation of a Roman Quadrireme (From the Naval Encyclopedia)

The Romans certainly knew the strategic value of Piraeus as it became a major naval base for the Roman fleet in the eastern Mediterranean which was often engaged in combatting the rampant piracy that took place in the region. Of course, as trade was central to the workings of the empire, there were customs offices operated by Rome to carry out the taxation of goods.

There were also some religious additions made by Rome to Piraeus, such as shrines to Jupiter and Neptune, which blended in with the existing shrines and temples to traditional Greek deities whom the Romans also respected.

These changes and more are an indication of the continued importance of Piraeus to Rome as a strategic maritime hub.

While the remains of Athens’ Golden Age continue to be the most glorious to behold, it is undeniable that Rome – despite the destruction it initially wrought on the city – more than made up for it with the monuments its emperors and well-to-do citizens constructed.

Today, Athens is among the most beautiful cities in the world, dotted with ancient monuments that are still marvels to see.

That said, Roman Athens in the early third century C.E., when our story takes place, must have been a wonder, something to rival the halls of Olympus itself.

If the Gods had a home on earth, Roman Athens must have been it.

Thank you for reading.

Artist impression of Roman Athens at its peak with the Ilissos River in the foreground and the Temple of Olympian Zeus centre-left.

There are more posts coming in The World of An Altar or Indignities, so make sure that you are subscribed to the Eagles and Dragons Publishing Newsletter so that you don’t miss any of them. When you subscribe you get the first prequel book in our #1 best-selling Eagles and Dragons series for FREE!

If you haven’t yet read any books in The Etrurian Players series, we highly recommend you begin with the multi award-winning first book Sincerity is a Goddess: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome.

In celebration of drama in the ancient world, be sure to check out our ‘Ancient Theatre’ Collection in the Eagles and Dragons Publishing AGORA on Etsy which features a range of ancient theatre-themed clothing, glassware and more! CLICK HERE to browse.

An Altar of Indignities: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome and Athens is now available in ebook, paperback and deluxe hardcover editions from all major online retailers, independent bookstores, brick and mortar chains, and your local public library.

CLICK HERE to buy a copy or get ISBN# information for the edition of your choice.

Brace yourselves! The Etrurian Players are back!

Thankyou for this absolutely astounding post. I loved it and I just wish that the Parthanon Marbles would be returned.

Thank you, Rita. So glad you enjoyed this post. And I agree, the Parthenon Marbles should go back to Greece. After all, they have a beautiful home in the new Acropolis Museum! Cheers 🙂