Salvete, readers and history-lovers!

Welcome to The World of Isle of the Blessed!

In this seven-part blog series, we’re going to be taking a look at the research that went into our latest historical fantasy release, Isle of the Blessed, Book IV in the #1 bestselling Eagles and Dragons series.

This will be a journey through the world of early third-century Roman Britain in which we will look at the history, archaeology, and historical events that took place during this pivotal time in the Roman Empire in which the book is set.

Part I – The Dragon’s Domus

At the very south ende of the chirche of South-Cadbyri standith Camallate, sumtyme a famose toun or castelle… The people can tell nothing ther but that they have hard say that Arture much resorted to Camallate. (John Leland, Royal Antiquary, 1532)

The hillfort of South Cadbury Castle in Somerset, England, is one of the major locations in Isle of the Blessed. However, most people are familiar with it as a site with strong Arthurian associations. As such, its importance and role is hotly debated.

Though Isle of the Blessed is not a story of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, it is difficult not to speak of this important Iron Age site without discussing the Arthurian connection.

Was South Cadbury Castle the power centre of the historical Romano-British warlord, or dux bellorum, we know as ‘King Arthur’? Was this the actual site of what has come to be known in the popular imagination as ‘Camelot’?

I’ve always been a strong proponent of the theory that there was in fact, an historical ‘Arthur’ who formed the factual basis for all the legends we love and cherish. So, when I look at sites such as South Cadbury, I do so with that in mind. However, that doesn’t mean that I accept a site’s association with Arthur on faith alone.

I know this site pretty well – as I studied it and wrote about it as part of my Master’s dissertation entitled “Camelot: A look at the historical, archaeological, and toponymic evidence for King Arthur’s Capital”. As part of this, I looked at three of the main candidates for Camelot that had been put forward at the time – Wroxeter (Roman Viroconium), Roxburgh Castle (in the Scottish Borders), and South Cadbury. There is a copy of the dissertation hidden somewhere in the stacks at the St. Andrews University library in Scotland.

South Cadbury Castle is also where I cut my teeth as an archaeologist as part of the South Cadbury Environs Project team for a couple of seasons under the leadership of Richard Tabor. This was a wonderful experience that helped me to get up close and personal with the site I had studied for so long – I dug test pits, got into bigger trenches in which curious cows came to watch what I was doing, carried out geophysical surveys with a magnetometer, and found some curious objects such as a bronze dolphin that formed the handle of a Roman drinking cup.

Most of all, I was given the chance to spend more time on this amazing, and yes, magical, landscape.

And a couple years ago, when doing research for Isle of the Blessed, I returned to South Cadbury where I also filmed a mini-documentary on the site (coming out later this year!).

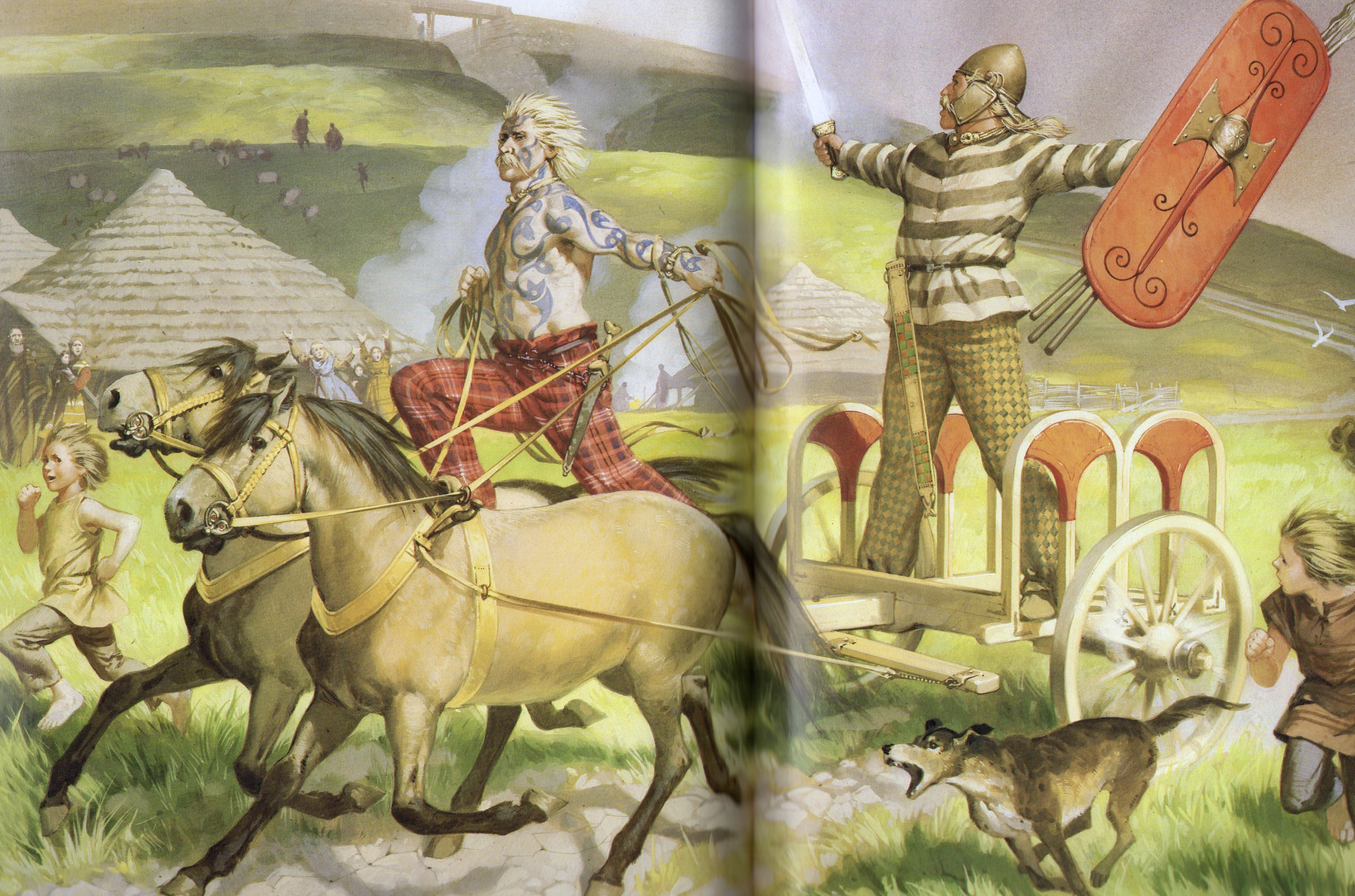

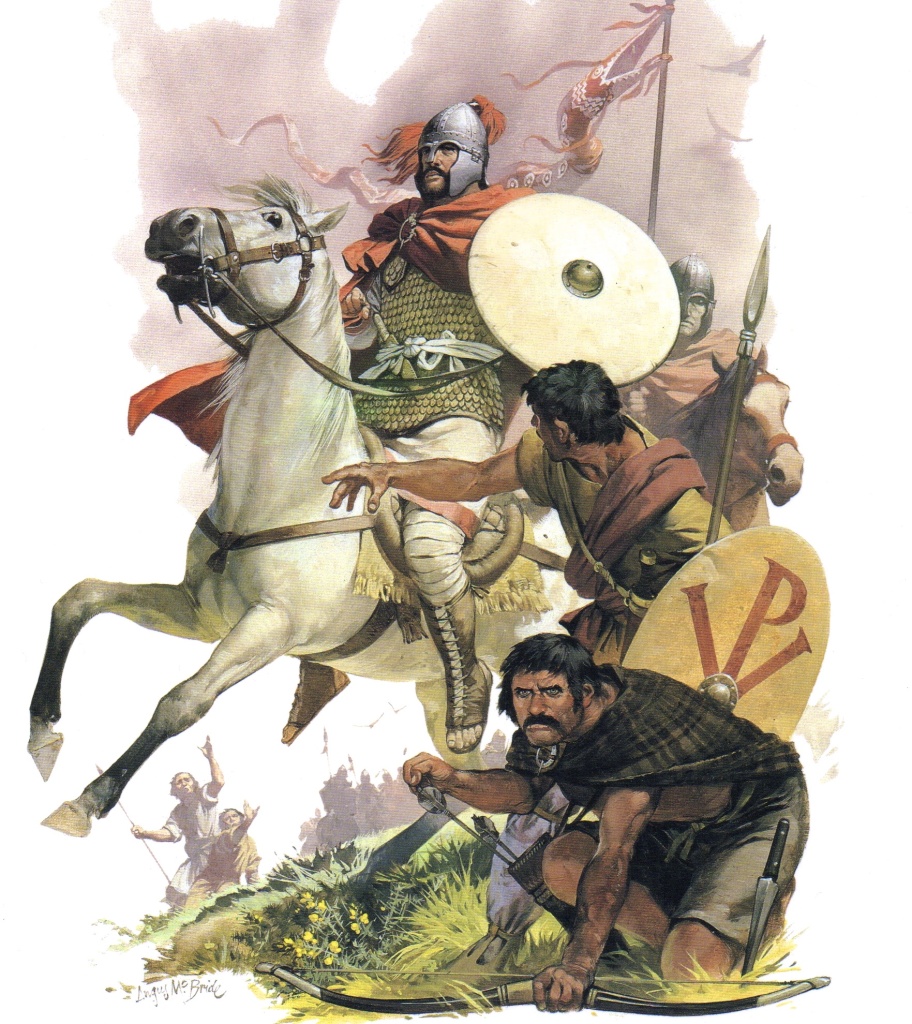

British Belgic Warriors of the Iron Age – Illustrated by Angus McBride (source – Rome’s Enemies 2 – Gallic and British Celts)

Before I give my thoughts on wandering the slopes of South Cadbury Castle, we should have a look at what it actually is.

South Cadbury Castle is not the late medieval castle with banners flying from tall towers that make up our usual image of Camelot. It is a 500 foot high Iron Age hillfort located in the pre-Roman era lands of the Durotriges. Occupation of the site began in the Neolithic period and it went through various stages of occupation from the 5th century B.C. onward.

By the time of the Roman invasion of Britain, it had four massive defensive ramparts with an inner area of about 18 acres. Access to the top was by two entrances, one to the north-east and the other, larger one, to the south-west. The Iron Age occupation of the site came to a violent end around A.D. 43 when Vespasian stormed the southern hillforts of Britannia.

The Romans made little use of the site, though there have been some theories that it was used as a Roman supply station. This theory is explored in Isle of the Blessed and the Eagles and Dragons series. In the 3rd and 4th centuries, there was renewed activity with visits being made to a Romano-Celtic temple that was built on the site.

Location of the Romano-British temple in the south-east sector of the hillfort of South Cadbury Castle

During excavations, a bronze letter ‘A’ was found that some believe belonged to this temple, which was perhaps dedicated to Mars, or some other deity.

However, when it comes to South Cadbury Castle, the periods that have always drawn me to it are the 5th and 6th centuries A.D. This period of the site is known as the ‘Arthurian’ period, and it is at this time, after Rome’s legions had left the island, that the archaeology shows a massive refortification of the hillfort.

6th Century British Warriors – Illustrated by Agnus McBride (source – Arthur and the Anglo-Saxon Wars)

Though it is much debated, South Cadbury’s association with the Arthurian period stems not just from hearsay and folklore. It has the archaeological evidence to back it up.

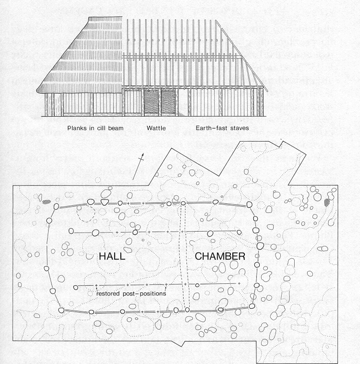

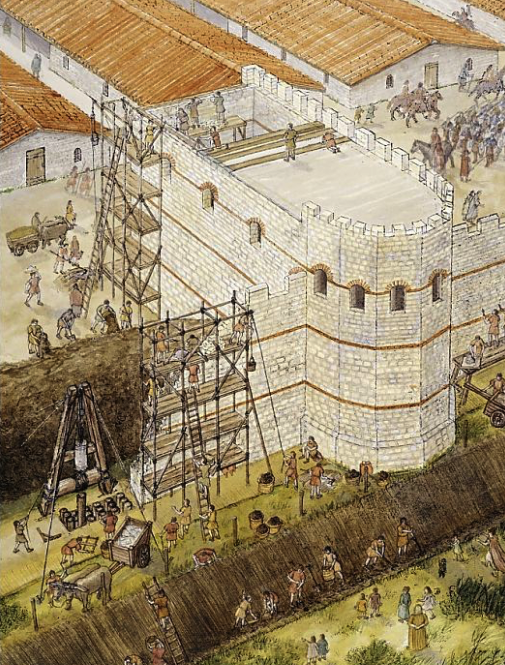

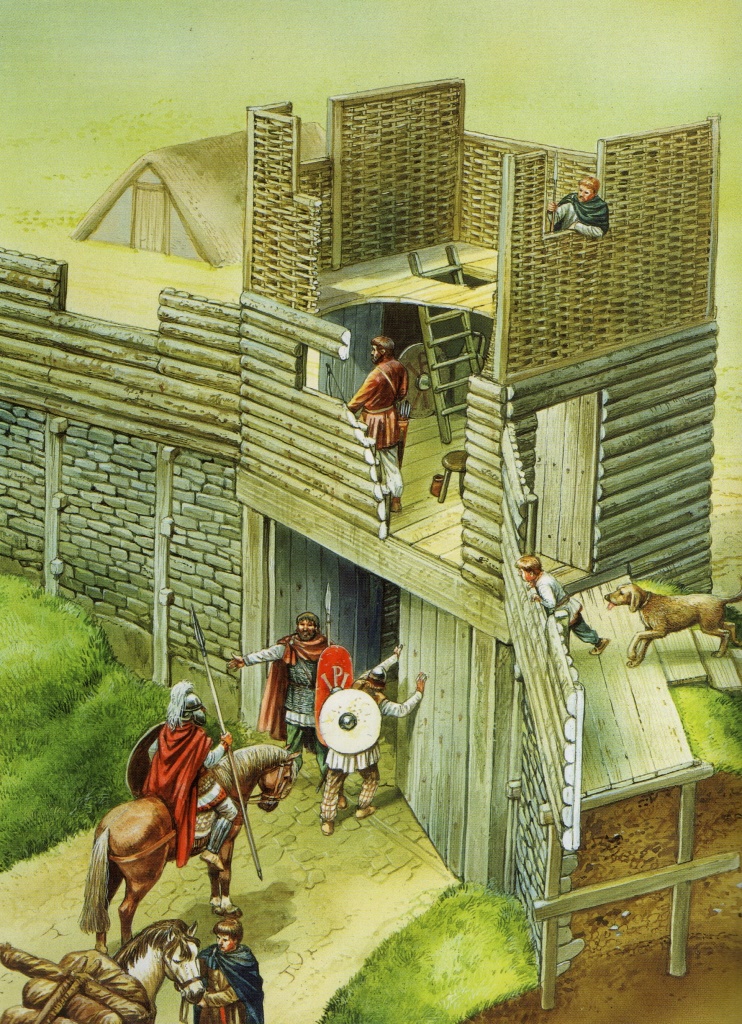

There have been a few big excavations of the hillfort over the years, but the biggest of all took place in the late 1960s and was headed by Professor Leslie Alcock. Professor Alcock and his team discovered evidence for a large scale occupation and refortification of the hillfort, during the Arthurian period, which showed repaired defences, including a strong gatehouse at the south-west entrance, and most importantly, several buildings, including a kitchen and a large timber hall on the fort’s high plateau.

The discovery of post holes reveals a finely-built timber hall that was on a large scale, measuring about 63×34 feet. This hall would not have been the great castle hall of late medieval romance, but rather something like the timber drinking halls of the period, more like to the Golden Hall of Meduseld, the seat of King Theoden in Lord of the Rings.

Another very telling discovery at Cadbury Castle was the large quantity of Mediterranean pottery that dates to the Arthurian period of activity. This is the same pottery type that was discovered at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall, a site that also has strong Arthurian associations. One might think that shards of pottery from wine, olives and olive oil might be pretty mundane, but they anchor the sites strongly in the period, and also show that someone of importance was associated with the site. Not everyone could afford to import such things through trade.

The refortification of the hillfort during the Arthurian period was on a massive scale, and would have required many resources and men to hold it. South Cadbury castle was, in a way, on the front lines of the British struggle against the invading Saxons, and would have been well-placed to meet the Saxons as they advanced westward.

Based on the refortification, and evidence of the gatehouse that linked the ramparts running over the cobbled road at the south-west corner, this place was likely the base for an army that was large by the standards of the period. It may have been the site of the court of the dux bellorum, or the historical Arthur.

Artist Reconstruction of the South-west gate – Illustrated by Peter Dennis (Source – British Forts in the Age of Arthur)

I am only scratching the surface here, as far as the archaeological finds. For a more academic look at South Cadbury Castle, you will want to read the upcoming Historia series release Camelot: The Historical, Archaeological and Toponymic Considerations for South Cadbury Castle as King Arthur’s Capital. (Make sure you are signed-up to the mailing list be notified of that release)

South Cadbury Castle was finally abandoned in the early 11th century when it was being used as a royal mint during the reign of the Saxon king, Aethelred.

Today, South Cadbury Castle is a quiet hill in the midst of the Somerset countryside where it lies just south of the A303 motorway. The levels of its steep ring fortifications are now overgrown with trees and scrub, and cows roam the fields surrounding it.

When you visit, you pull your car into the small car park at the south end of the village of South Cadbury, just east of the hillfort. From the lane, you can’t really tell what you’re looking at. It seems like a steep, forested hill with a path leading up.

This path leads up to the north-east gate of the hillfort, and for me, it was always the gateway to another time, another realm.

It’s difficult to approach this site and reconcile the archaeologist/historian side of me with the romantic. Arthurian lore runs deep in my veins, and has had a hold on my psyche since I was very young. The first time I visited the site, I could almost hear the call of clear trumpets and the thumping of horses’ hooves upon the ground as knights returned home from their adventures, their horses brightly caparisoned, their armour shining brightly in the light of the Summer Country.

Of course, I know that is not how it was during the Arthurian period, but this is a place and story that fires the imagination. Cadbury Castle’s associations with Arthur include a hollow hill where he sleeps until he is needed again, the site of ‘Arthur’s Well’, a place on the slopes where his horse drank when he led the Wild Hunt, and of course the location of Camelot.

To me, however, the idea of South Cadbury as the main fortress of a Romano-British warlord leading a group of skilled cavalry in a last stand against the invading Saxons is no less romantic.

During my subsequent visits, I would ascend the dirt and rock path leading up to the northeast gate and pause with reverence for the history of the place. I would imagine looking ahead, up the slope to the central plateau of the hillfort to the great wooden hall where smoke from the hearth of Arthur’s hall wafted into the sky as he and his warriors discussed the fight for their lives and their Romano-British heritage.

The warriors that manned the ramparts of South Cadbury, who dined in the hall, and who rode out to meet the Saxons, have been wrapped in the fabric of myth, as much as the Isle of Avalon not ten miles distant, in Glastonbury. But they certainly left a mark on the place, on history and folklore.

As I walk the grass-covered ramparts of South Cadbury, watching the crows dive in the winds above the steep slopes, I can’t help but wonder if Arthur, Gawain, Bors, Tristan, Bedwyr, Cai and others walked that same path, a wary eye out for a sign of the enemy that would shatter the peace they had fought so hard for at the famed battle of Mons Badonicus.

Rarely have I felt so at peace and nostalgic as I have when walking around this hillfort. I can still smell the damp grass and feel the sun on my face. In my mind, I still watch the puffs of white cloud blowing over the Somerset landscape as I pause to gaze to the north-west and see Glastonbury Tor rising out of the earth.

In ages past, when the levels flooded, the distance between Cadbury Castle and Glastonbury might have been crossed by boat if you knew the way and which rivers to take. Indeed, one of the discoveries found around the hillfort was a boat.

South Cadbury Castle is, in some ways, closely tied to Avalon, and you can feel that as you look from the top of one to the other. This too is explored in Isle of the Blessed.

After making a round of the ramparts, and standing on the roadway of the south-west gate, I would always spend a good amount of time on the plateau, watching the sky and letting my imagination take hold.

The beauty of visiting a site, rather than looking at in a book or online, is that direct connection with the past, with the history of the place.

Yes, many of the stories we know and love about Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table are medieval fabrications. But I do believe that every legend has its base in fact, and so it’s a comfort to know that the layers of myth and legend are veined with elements of possible truth and history.

Many people will disagree, and that’s ok. When it comes to Arthur we will never reach a consensus.

However, considering the archaeological evidence at South Cadbury Castle, along with its location and the apparent activity during the Arthurian period, it seems quite possible that if there was an historical Arthur, he would undoubtedly have been familiar with this magnificent hillfort.

Was this just another strong point in the British defensive network? Or was it the Arthurian power centre that has come to be known as Camelot?

Whatever the answer is, it is surely fascinating, and perhaps unattainable. But then, that is what makes these historical mysteries so intriguing.

If you ever manage to roam the lands In Insula Avalonia, just be sure to make your way to South Cadbury Castle. Walk up the steep slopes, and through the gate, and know that you may just be walking in the footsteps of Arthur.

Part II – Roman Lindinis: The Small Town with Big Ambitions

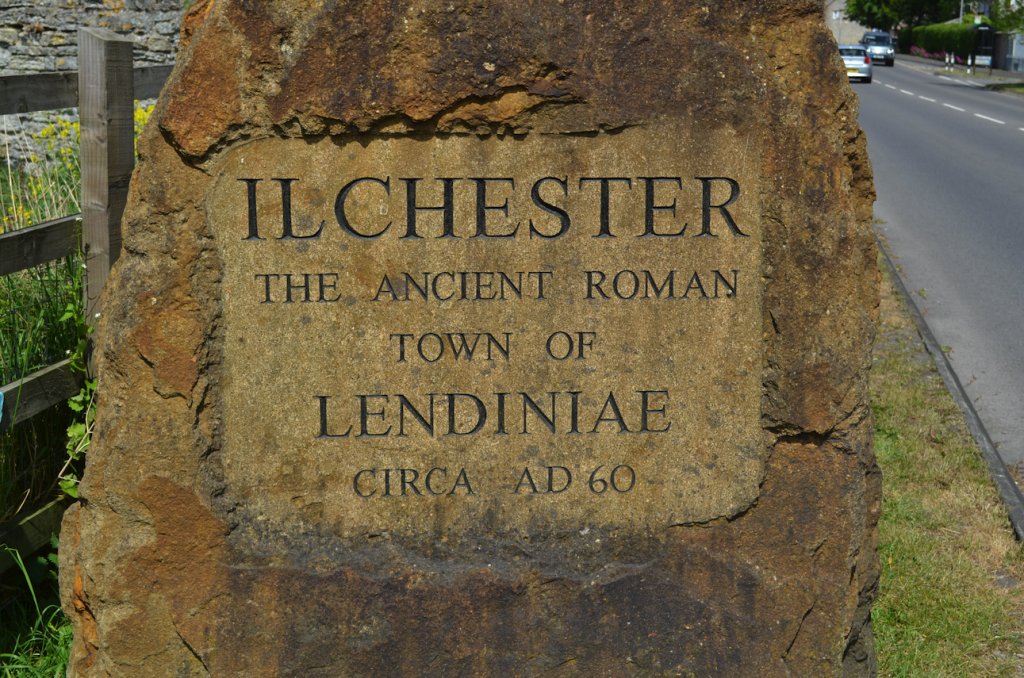

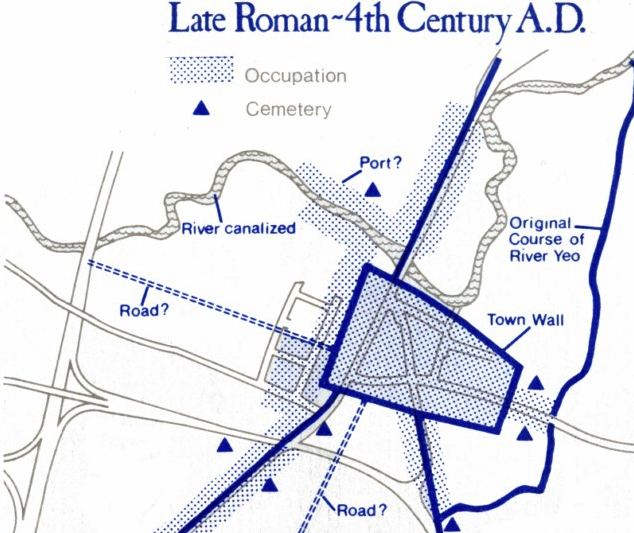

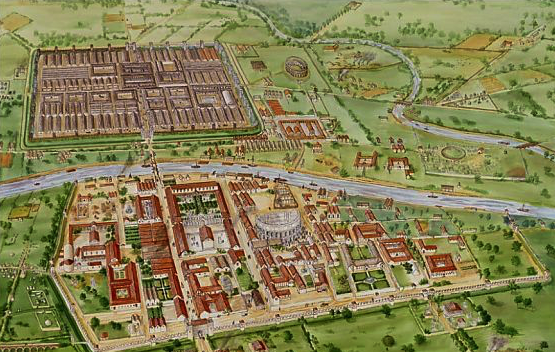

The settlement of Lindinis (also known as ‘Lendiniae’), as it is known in the seventh century Ravenna Cosmography (a list of place names from India to Ireland) is actually modern Ilchester, in Somerset, England.

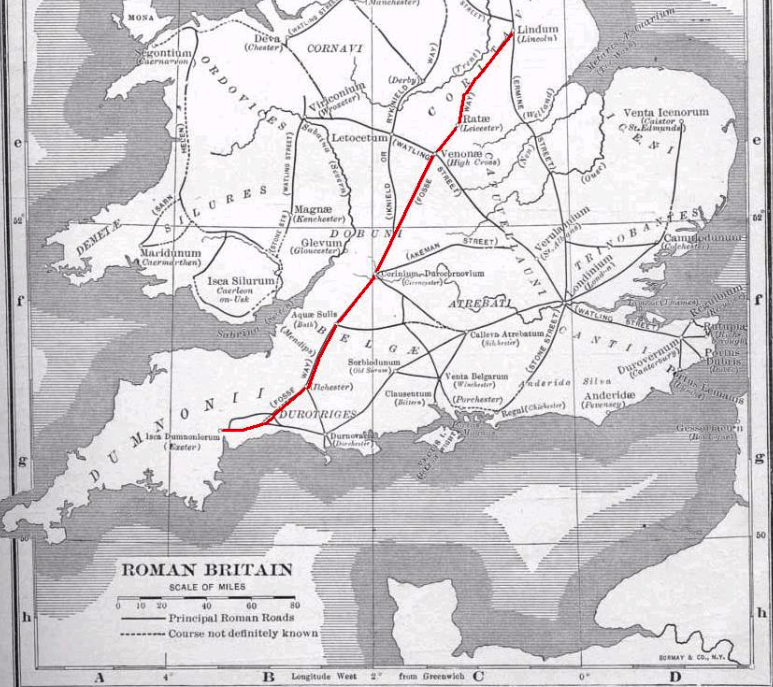

Lindinis, as it was known during the Roman period, was located just a few miles from South Cadbury Castle, and Glastonbury, Somerset. This fifty acre settlement lies where the Dorchester road interests with the Fosse Way, one of the major roads of Roman Britain.

During the Roman period, Somerset was an agriculturally rich area of the Empire, with many villa estates, such as that of Pitney (which also features in the story). These estates’ primary business was in crops such as spelt wheat, oats, barley and rye. The also raised livestock, mainly cattle, but also sheep, horses, goats, and pigs.

These Roman villa owners were wealthy, and Lindinis was one of the main markets where they brought their crops and livestock.

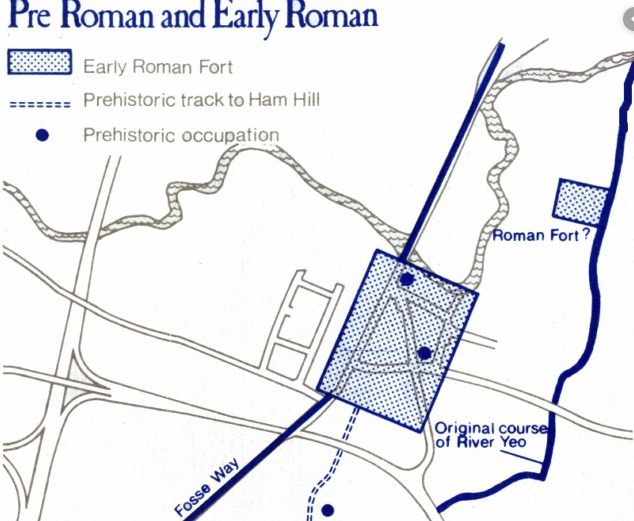

Lindinis was not always a Roman settlement, however.

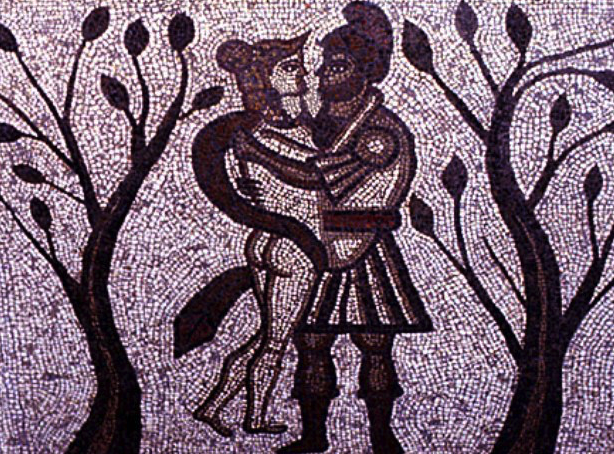

It was originally a Celtic oppidum, a native center that consisted of a large enclosure with homes, food stores and livestock. One imagines Celtic Somerset as a place of peace and vitality.

But, in A.D. 43 the Romans arrived with the advent of the Claudian invasion of Britain. Forty-five thousand troops marched over the land, including four legions, and the native Britons fought, and lost. Vespasian, the future emperor, stormed the southern hillforts of Britain, including South Cadbury Castle, ushering in an age of Roman domination.

Eventually, at Lindinis, two successive forts were built on the site to the south of the river: one from Nero’s reign, and another during the Flavian period. There is also evidence for a third fort to the northeast of the river crossing where a double ditch enclosure has been discovered.

The Roman invasion of Britain was a violent time, and that violence carried on through the Boudiccan revolt of A.D. 59. But when the blood stopped flowing, an age of Pax Romana settled on the southwest of Britannia, and Lindinis was at the heart of it.

Lindinis, however, was not the main settlement of Roman Somerset. To maintain peace and order, and keep the economy running, the Romans instituted various civitates, centres of local government in which tribal groups of the region participated.

The council of a civitas was known as an ordo, and the members of the ordo were decurions, overseen by an executive, elected curia of two men. The ordo of a civitas usually included Romans, tribal aristocrats or local chieftains, and it was their job to administer local justice, put on public shows, see to religious taxation, the census, and represent the civitas in Londinium. Supreme authority, however, belonged to the Provincial Governor who was aided by a procurator, the ‘tax man’.

There were three major civitates during the Roman period in southwestern Britannia: Durnovaria (modern Dorchester) the civitas of the Durotriges tribe, Isca Dumnoniorum (modern Exeter) the civitas of the Dumnonii, and to the north Corinium Dobunnorum (modern Cirencester) the tribal centre of the Dobunni.

Despite its large market and location at a crossroads along the artery of the Fosse Way over the river Yoe – in the southwest, the Fosse Way ran from Isca Dumnoniorum (modern Exeter) to Aquae Sulis (modern Bath) – Lindinis was not one of the major civitates of the region, though it did rival nearby Durnovaria.

In addition to a thriving market where wine, oil, clothing, ornaments, jewellery, tools, pottery and glass were sold, Lindinis also had gravel and stone streets, and stone walls (later). People also came to Lindinis to pay their taxes.

Where the road diverges in Ilchester – the left to Exeter, the right to Dorchester. See the bridge over the river directly ahead.

There was also a small garrison.

Lindinis may have seen itself as the civitas Durotrigum Lendiniensium, but it could not be an official civitas as one of the requirements for civitas status was a basilica or forum. Lindinis did not have either of those.

Roman Lindinis had a large role to play in the economy of Roman Somerset, but perhaps not as large as its ordo would have liked. It also found itself in difficult situations during its time, for during the civil war (A.D. 193) between Septimius Severus, Pescennius Niger, and Clodius Albinus, Lindinis was forced to declare for Clodius Albinus who was in Britannia when he made his claim. At this time, new defences were built around Lindinis, as if in anticipation of the trouble to come.

In the book, Isle of the Blessed, Lucius Metellus Anguis, the main protagonist in the Eagles and Dragons series, has several run-ins with the ordo members of Lindinis’ ruling council who see him as a person of influence at the imperial court, a man who could help their small town to become much more.

Historically, despite its lack of a proper forum or basilica, it seems that Lindinis did succeed in attaining a measure of civitas status, for along Hadrian’s Wall, two inscriptions have been found bearing the name of a detachment from the ‘Civitas Durotragum Lendiniensis’, or the ‘Lindinis tribe of the Durotriges’.

This, despite the presence of the other three, official civitas settlements Durnovaria, Isca, and Corinium.

Who knows? Perhaps the persuasiveness of the ordo members of Lindinis, the settlement’s important location, and the size of its market helped to sway the Roman authorities to grant civitas status.

In Isle of the Blessed, we see how far the local politicians are willing to go.

Part III – Ynis Wytrin: The Place Beyond the Mists

What is the Isle of the Blessed?

There are many traditions when it comes to paradise, or a place where there is no suffering or pain. To the ancient Greeks, the Fortunate Isles, or Isles of the Blessed were a place where heroes went, a green paradise where the sun always shone. To the Romans, that was Elysium, or the Elysian Fields, the place where heroes blessed by the Gods went to spend eternity in peace.

In the latest Eagles and Dragons series novel, Isle of the Blessed, we find ourselves in a world beyond the water and mist of the Somerset levels of southern Britannia.

In Part III of The World of Isle of the Blessed, we’re looking at the history, myth and legend of the place known in Celtic myth as Ynis Wytrin, but which we know today as Glastonbury, or the legendary Isle of Avalon.

Glastonbury has always been a special place for me, not because I lived in the countryside outside the town for a few years, or because of its strong Arthurian associations, an area of study and story that I have always gravitated to.

One of the things I love about Glastonbury is the, more often than not, peaceful coming together of various beliefs through the ages.

To most, the mere mention of this town’s name will likely conjure images of wild, scantily clad or naked youths and aged hippies. You’ll think of thousands of people covered in mud as they wend their way, higher than the Hindu Kush, among the tent rows to see their favourite artists rock the Pyramid Stage at Britains’ largest music festival.

It’s a great party, but that’s not the real Glastonbury.

Removed from the fantastic orgy of the music festival, this small, ancient town in southwest Britain is a place of mystery, lore and legend. It is a place that was sacred to the Celts, pagan and Christian alike, Saxons, and Normans. For many it is the heart of Arthurian tradition, and for some it is the resting place of the Holy Grail.

Today, Glastonbury is a place where those seeking spiritual enlightenment are drawn. The New Age movement is going strong here, yet another layer of belief to cloak the place.

When I lived there, I never tired of walking around Glastonbury and exploring the many sites that make it truly unique. I’d like to share some of those sites with you, sites that are featured in Isle of the Blessed, the latest Eagles and Dragons novel.

From where I lived on the other side of the peat moors, I awoke every morning to see Glastonbury’s most prominent feature shrouded in mist – the Tor.

Tor is a word of Celtic origin referring to ‘belly’ in Welsh or a ‘bulging hill’ in Gaelic. Glastonbury Tor thrusts up from the Somerset levels like a beacon for miles around. Every angle is interesting. On the top is the tower of what was the church of St. Michael, a remnant of the 14th century. Before that, there was a monastery that dated to about the 9th century A.D.

However, habitation of this place goes much farther back in time with some evidence for people in the area around 3000 B.C. It was not always a religious centre. In the Dark Ages, the Tor served a more militaristic purpose and there are remains from this period too.

In Arthurian lore, the Isle of Avalon is a sort of mist-shrouded world that is surrounded by water and can only be reached by boat or secret path. In fact, during the Dark Ages and into later centuries, until the drainage dykes were built, the Somerset levels were prone to flooding. This flooding made Glastonbury Tor and the smaller hills around it true islands. With the early morning mist that covers the levels, this watery land would have been a relatively safe refuge for the Druids, and early Christians, Dark Age warlords and medieval monks.

In Celtic myth, Glastonbury Tor, one of the traditional gates of Annwn, the Celtic otherworld, is said to be the home of Gwyn ap Nudd, the Faery King and Lord of Annwn.

Gwyn ap Nudd is the Guardian of the Gates of Annwn, an underworld god. It is at Samhain that the gates of Annwn open. This was also the place where the soul of a Celt awaited rebirth.

If you are on the Tor at Samhain, you may hear the sound of hounds and hunting horns as the lord of Annwn emerges for the Wild Hunt of legend.

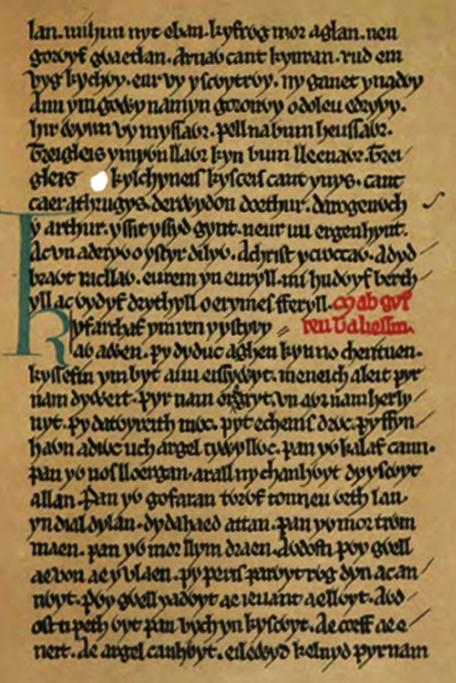

In Arthurian romance, there is a tradition of the wicked Melwas imprisoning Guinevere on the Tor. Arthur rides to the rescue, attacks Melwas and saves Guinevere. This particular story mirrors an episode in Culhwch and Olwen, one part of the Welsh Mabinogion, in which Gwythyr ap Greidawl attempts to save Creiddylad, daughter of Lludd, whom he is supposed to marry, from Gwyn ap Nudd himself.

Another even more fascinating Arthurian connection can be found in a pre-Christian version of the ‘Quest of the Holy Grail’, called the ‘Spoils of Annwn’ which was found in the ‘Book of Taliesin’. In this tale, Arthur and his companions enter Annwn to bring back a magical cauldron of plenty. In this, some say that ‘Corbenic Castle’ (the ‘Grail Castle’) is actually Glastonbury Tor. It isn’t just Herakles and Odysseus who journeyed to the Underworld!

Glastonbury Tor is not only associated with Celtic religion, myth and legend. It is also said by some to be a place of power or a sort of vortex in the land that lies along some of the key ley lines, including what is called the St. Michael ley line. The majority of sites associated with St. Michael, the slayer of Satan, along the ley line were indeed places of power and belief of the old pagan religions.

Myth and legend persist through story and place, and the Tor is a prime example of how successive traditions do not overcome each other, but rather combine to make up the various aspects of that place.

If you ever get to Glastonbury, the Tor is a definite must. Walk to the top and sit awhile. Look out over the landscape and watch the crows and magpies dive in the wind around the steep slopes. Close your eyes and listen. While you’re there, you can decide whether you are sitting on a natural formation, a ceremonial labyrinth, a hillfort, a sleeping dragon, the Gates of Annwn, or the mound where Arthur sleeps until he is needed once more. The Tor is all of these things.

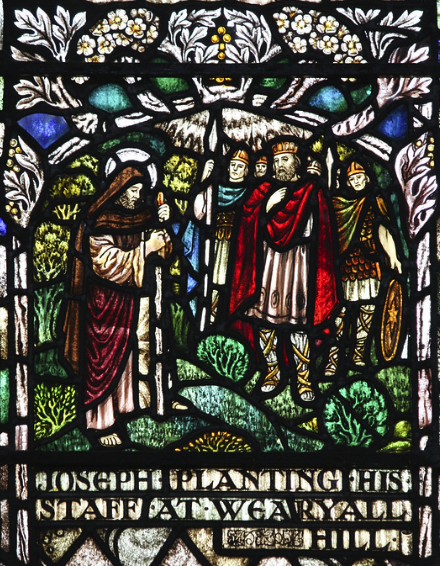

Another prominent feature of Glastonbury’s landscape is known as Wearyall Hill, located on the road as you enter from the neighbouring town of Street.

Wearyall Hill is home to one of Glastonbury’s most ancient treasures – the Holy Thorn.

Across the street from the Morrison’s store, you can climb up Wearyall’s gentle slope to see a hawthorn tree known as the Glastonbury Thorn, or the ‘Holy Thorn’. One popular legend associated with Wearyall Hill and the Holy Thorn is that in the years after Christ’s death, his uncle Joseph of Arimathea came with twelve followers by boat to Glastonbury. When they set foot on the hill, tired from their journey, Joseph plunged his staff into the ground and it took root.

There is archaeological evidence for a dock or wharf on the slopes of Wearyall Hill that dates from the period. Did Joseph of Arimathea actually arrive in Britain with the Holy Grail?

Stained glass detail from St John’s church in Glastonbury showing Joseph planting his staff in Wearyall Hill.

Well, that depends on what you believe. And Glastonbury is just that, an amalgam of beliefs living, for the most part, in harmony, just as the Celts and early Christians did here over two thousand years ago.

Cuttings of the Thorn grow in three places in Glastonbury. What is interesting is that this variety of hawthorn is not native to Britain, but is rather a Syrian variety. Curiously, it flowers at Christmas and Easter, both sacred times of year for Pagans and Christians. Every holiday season, the Royal family is sent a clipping of this very special tree that hails from the earliest days of Christianity in Britain.

The current Thorn is not the original, but rather a descendant of the original which was burned down by Cromwell’s Puritans in the seventeenth century as a ‘relic of superstition’. How much destruction has been wrought on the ancient sites of Britain during the wars waged by Henry VIII and later Oliver Cromwell? It’s horrifying to think about.

As with all other things in Glastonbury, Wearyall Hill and the Holy Thorn do not belong solely to the Christian past.

The hawthorn tree was one of the most sacred trees to the Celts and is the sixth tree on the Druid tree calendar and alphabet. It is also known as the ‘May Tree’ because of when it blossoms most. May was sacred to the ancient Celts as the time of the festival of Beltane, a time for Spring ritual and worship of the Goddess.

In the Middle Ages, the practice of picking hawthorn boughs evolved to include dancing with them around a May Pole.

In Arthurian tradition, Wearyall Hill is associated with the castle of the ‘King Fisherman’ whom the Grail knights meet. To reach the castle, those on the quest were said to have to cross the ‘perilous bridge’ over the river of Death. To pass through the castle was to go from this world to the next.

Interesting to think that the gates to the otherworld of Annwn were believed to be just on the next hill, Glastonbury Tor.

Whatever legend or myth you believe, or don’t believe, about Wearyall Hill is up to you. The stories are many and convoluted, but such is the fate of great and sacred places of the past.

I always looked forward to my walks up the gentle slope of Wearyall Hill with the Holy Thorn drawing me up like a beacon, a friend even. Locals, Christian and Pagan believers, hold it close to their hearts.

Once at the top of the hill, I would circle the Thorn, reach out to touch its limbs, and read some of the wishes or prayers on ribbons tied to it – ‘Don’t let me lose my family,’ or ‘Thank you for making my mummy better.’ The wishes wrenched your heart, and the thanks made you smile.

When I would sit on the nearby bench at the top of the hill, I never felt alone. I would look out at the Tor and the surrounding landscape and feel tremendous gratitude. I would always leave with a sense of hope for the future, and a tie to the past.

On my recent visit, long after the vandals struck, there are more wishes than ever upon the Holy Thorn.

When I returned to Glastonbury recently to film a documentary and do some research for Isle of the Blessed, I found the tree much changed from before.

In 2010, vandals took a chainsaw to the Holy Thorn in the middle of the night. In the morning, residents found their beloved tree of hope hacked to bits. A sapling was planted again in the Spring of 2013, but again, that was knocked down in the night.

I’m still in shock over this, lost in my remembrances of Glastonbury’s Thorn in full bloom on a sunlit hilltop.

But the Thorn has survived the centuries and there has been talk that new shoots have been coming up. The Royal Botanical Gardens is on the case, and so are the citizens of Glastonbury.

The Thorn and Wearyall Hill itself are not purely Christian or Pagan. They are symbols of unity, and of a common past. We should indeed cherish sites that are so revered, whether we believe in them or not.

In a way, the Thorn’s sacrifice is bringing people together. Glastonbury is still a town where Pagan and Christian live side by side.

And it is this unity that I explore in Isle of the Blessed.

I have every hope that the Thorn will blossom once again on the crest of Wearyall Hill, and that one day I’ll make the climb to say hello to a very old friend.

This next site we are going to look at is one that, like the rest of Glastonbury, is suffused with layers of history, legend, and belief.

The Chalice Well and surrounding gardens, located in a valley between Chalice Hill and the Tor, is one of those places that you don’t quite know what to make of at first. When you enter under the vine-covered pergola you are met by colour, soft light, and the gentle trickle of water playing about your senses.

You see young, wildly coloured blossoms exploding from the soil at the foot of Yew trees that have seen centuries of summers in Ynis Wytrin.

The same goes for the people visiting this place.

You will see young children frolicking like fairies at the edge of the water, adults of all ages contemplating beauty…life…death.

And you will find aged men and women, whose years are beyond the care of counting, strolling silently about the gardens. They’ll admire a particularly beautiful blossom or sit on one of the many benches hidden in private corners, perhaps remembering others they have come here with long ago. Or maybe they are just looking up at the Tor and harkening back to the tales of Arthur they loved when they too were children.

The thing about this place is its overwhelming sense of peace and harmony, from which all can benefit.

But what exactly is the Chalice Well?

Scientifically-speaking, Chalice Well is actually an iron-rich spring, the source of which is unknown. Some believe it comes from deep in the Mendip Hills to the north. The Chalice Well is where it comes out of the ground.

Springs were sacred to the ancient Celts. To those who inhabited this area from the pre-historic era on, the Well may have been a healing place beside the Tor. The waters that run red were sacred to the Goddess and were her water of life.

The spring has never failed, even in drought.

‘The Druids; or the conversion of the Britons to Christianity’. Engraving by S.F. Ravenet, 1752, after F. Hayman.

It is also believed that Glastonbury was the site of a Druid ‘college’ of instruction and that the avenue of sacred Yew trees, some still remaining in the Chalice Well gardens, were part of a processional way to the Tor, passing beside the Well.

Later legend, and the reason for the name given to the Well, relates how Joseph of Arimathea brought the Holy Grail to Glastonbury in A.D. 37. It is said that he buried the Grail near the Well and that the water runs through it, hence the redness of the water.

The Goddess’s blood was replaced by that of Christ, but the sanctity of the place remained (and remains) intact.

Of course, there is an Arthurian connection. Where you find the Grail, there too will you find Arthur and his knights.

In the 15th century, Sir Thomas Malory mentions the spring in his Morte d’Arthur when Lancelot and others are said to have retired as hermits in a valley near Glastonbury. Some believe it was this site that he referred to.

The sacred water of the Chalice Well feels like the beating heart of the gardens that surround it, and visitors, like a protective shield.

There are four places where the water surfaces in the Gardens.

The first is one of the most striking features – the well cover in the form of the Vescica Piscis.

The Vescica Piscis is an ancient symbol that represents the intersection of the material and immaterial (Natural and Supernatural) worlds. Fitting for one of the traditional gateways to Annwn.

The Chalice Well cover is made of English oak and wrought iron, and was designed after WWI by the architect and clairvoyant, Frederick Bligh Bond, who carried out the first excavations on Glastonbury Abbey.

The difference with this Vescica Piscis is that the circles are intersected by a sword, or bleeding lance, a Christian addition to this ancient symbol of power.

From the Well, the red water flows to the Lion’s Head where people can go to drink, or sit in quiet reflection while the water splashes onto a stone below.

Farther down the garden you come to a striking rich-red waterfall where the spring cascades into a pool where people can soak themselves in the healing water. This pool is another place of meditation known as Arthur’s Courtyard.

After that, the water flows past two ancient Yew trees, and a shoot of the Holy Thorn (yes, it survives!) into a pool shaped like the Vescica Piscis near where you enter the Gardens. The spring then flows away underground, beneath the Abbey and the pavement of Magdalene Street.

The red water’s healing sojourn above ground is fleeting, but for thousands of years it has brought people comfort, and peace.

Whenever I would visit Chalice Well and the gardens, my head pounding from a migraine, or the weight of a world of worries pressing me down, I would always leave feeling rejuvenated, calm, and optimistic.

Whether visitors are pagan, Wiccan, atheist, or Christian, or they adhere to some other system of belief, the Chalice Well is a place where people still believe in miracles, as they have done for thousands of years.

On the next part of our journey through Ynis Wytrin, or in insula Avalonia, we’re going to meet two very special giants.

They are tall, and broad, and green, and together they have stood the test of time. Their names are Gog and Magog.

The names of Gog and Magog will be well-known to Old Testament historians as evil powers to be overcome in the Book of Ezekiel (38-39), and in the New Testament Book of Revelation (20).

Gog and Magog also figure largely in the British foundation myths, mainly in the Historia Regum Britanniae of Geoffrey of Monmouth.

According to Geoffrey, when Brute, a descendant of the Trojan Aeneas, came to Britain in around 1130 B.C. he and his people fought a West Country giant(s) named Goemagot.

There are many other tales and places around England and Ireland associated with the giants, Gog and Magog.

In Glastonbury it is different.

The giants of which I speak are two ancient and magnificent oak trees that are tucked away in this misty isle.

They are not war, or pain, or suffering. Gog and Magog represent the last of the great oaks of Avalon. They demand nothing of the wanderer, and yet they are revered.

The association with the giants only goes so far as the names of the trees, and their size.

The short walk to the oaks from the middle of Glastonbury town is one of the most beautiful walks in the area.

Cross Chilkwell Street, near the Abbey Barn, and head up Wellhouse Lane between the slopes of the Tor and Chalice Hill. Follow the foot path into the field where you will come to the ancient trail of Paradise Lane. At the bottom of Paradise Lane, you will find Gog and Magog waiting for you.

These trees are ancient, no doubt. When they come into view, you are drawn to them as if to a comforting grandparent. You’ll find the odd ribbon tied to a branch, or a sheaf of wheat laid in offering among the sturdy limbs.

These two trees are friends to many in Glastonbury and beyond.

Gog and Magog are all that remain of an avenue of oaks that led to the Tor, and which was thought to be used as a processional way by the Druids in ages past.

Sadly, the avenue was cut down for farmland in 1906, and these two giants are all that remain.

Oak trees like Gog and Magog were sacred to worshippers of the Great Mother, and later the Druids. Before Rome and mass farming came to Britain, the whole of the south of Britain was covered in forests from Hampshire to Devon.

Oak groves were sacred, the sites of the Goddess’ perpetually burning fires and the rites of the Druids who used oak leaves in their rituals.

The sanctity of the oak was not relegated to Celtic Europe either, but also goes back to ancient Greece. At the sanctuary of Zeus at Dodona, priests would glean the will of Zeus from the rustling of the leaves in the sacred oak groves.

At Glastonbury, Gog and Magog would likely have seen many a ritual or procession.

If they could only speak in a way we could understand, I’m sure they would have some fantastic tales to tell.

Taking the walk from town, past the Tor, and down Paradise Lane to see Gog and Magog was always one of my favourite walks. Because there are no roads nearby, the sound of cars is absent, and all you can hear is the chirruping of birds and the whisper of the wind as it blows across the Somerset levels.

When I returned there to do research for Isle of the Blessed, my feet found their way there once more, whisking through the dry field grass, or squelching through the mud, until I caught that first glimpse of the two giants.

“It’s good to see you again, after so long…” I thought, feeling a great comfort and sense of gratitude.

From my days in insula Avalonia, I can still recall refreshing walks along the crest of Wearyall Hill, along the dragon’s back of the Tor, and down Paradise Lane to Gog and Magog.

However, there is another place of peace, a sanctuary in the middle of town, nestled between Wearyall Hill, Chalice Hill, and the Tor. It is Glastonbury Abbey.

The Abbey grounds, like other sanctuaries in town, are a place to get away to. You have to pay to get in, but once you walk through the arch, past another descendent of the Holy Thorn, and onto the green lawns surrounding these magnificent ruins, you are set to experience a whole new aspect of Glastonbury.

The ruins of what was once one of the largest abbeys in England rise up from the soft ground, sentry-still, surrounded by mist. ‘Majestic’ is a word I would use to describe the ruins, and ‘sad’. When you see the model of what the place looked like at its height of power and prominence, you understand.

Glastonbury abbey was not always such a soaring monument of Christianity. The lovely ruins that can be seen today are a medieval creation, the remains of which date from the twelfth to sixteenth centuries. But the place itself is said to be the site of the first Christian church and oldest religious foundation in the British Isles.

Model in the abbey museum of what Glastonbury Abbey used to look like before the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

According to tradition, Joseph of Arimathea and his followers built a wattle church on the site on land he was given by the local king, Arviragus (possible ruler of South Cadbury Castle at the time) around the middle of the first century A.D.

Circa A.D. 160, two Christians named Faganus and Deruvianus are supposed to have added a stone structure on the site of what is the Lady Chapel. It is here that there is an ancient well dedicated to St. Joseph.

In the early days of Christianity in Britain, this first chapel and the well were the predecessors of the magnificent ruins of the abbey we see today. The Lady Chapel was the site of the first Marian cult in Britain, and in the words of Geoffrey Ashe “there is no rival tradition whatsoever. When all of the fantastic mists have dispersed, ‘Our Lady St. Mary of Glastonbury’ remains a time-hallowed title.”

In one of the Welsh Triads, Glastonbury is given the distinction of having a ‘perpetual choir’.

It was a place that Christians gravitated to. Indeed, several Celtic saints are said to have come here, including St. Bridget, St. David, St. Columba, and even St. Patrick whom some stories name as the first abbot of Glastonbury.

Walking the grounds of Glastonbury Abbey is a contemplative activity, like so many other spots in insula Avalonia.

It is supremely peaceful and there are all manner of flora in the gardens to add to the calm. Great trees shiver overhead when a breeze blows into town from across the Somerset levels.

You can stroll the scant remains of the cloisters and up the nave with the abbey’s stone titans looming over you. In a couple spots, you can lift a wooden cover to reveal some of the colourful tiles of the medieval abbey floor.

Then, toward the transept, you come to an unassuming outline in the grass with a plaque marking it.

This is where you meet with one of Glastonbury Abbey’s most mysterious connections.

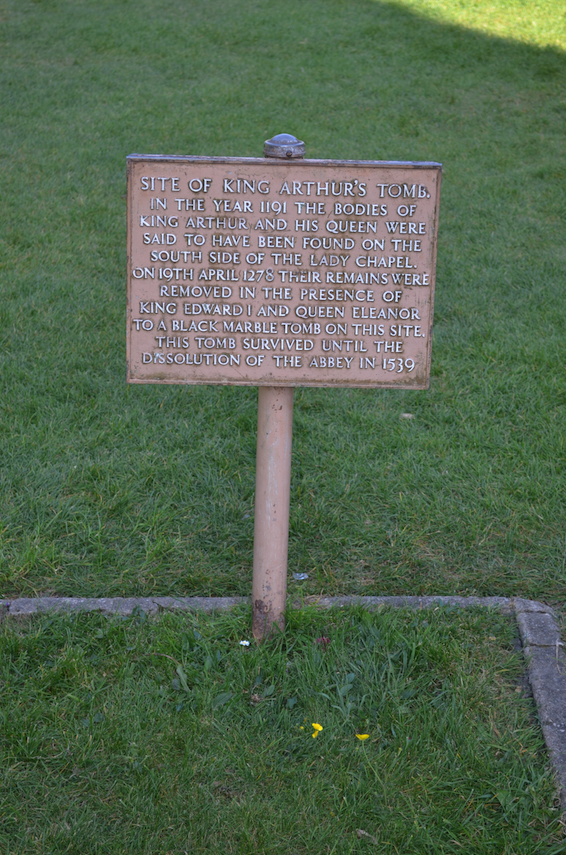

In 1184 a fire ravaged the abbey and the monks needed to rebuild. Around the time of the fire, a Welsh bard is supposed to have revealed to King Henry II that King Arthur himself was buried within the abbey grounds.

The king passed this information on to the Abbot of Glastonbury who later ordered excavations to be carried out. In 1191, it is said that the monks found the bones of a man and a woman in a hollowed out tree trunk who were none other than Arthur, and his queen, Guinevere.

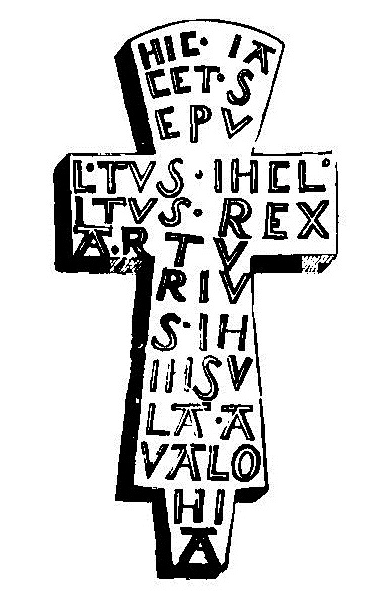

With the remains was a lead cross with the words ‘Hic Jiacet Sepultus Inclytus Rex Arturius in Insula Avallonia’ which translates as ‘Here lies buried the renowned King Arthur in the Isle of Avalon’.

The Elizabethan antiquarian, William Camden, did a sketch of the Arthur cross in the early 17th century.

A lot of doubt has been cast on the monks’ discovery with many believing that it was a hoax created by the monks to boost tourism through pilgrimage. The remains were treated as relics and later moved within the abbey during the reign of Edward I in the early 13th century.

It is important to note that the archaeologist who excavated the abbey in the 1960s, Dr. Ralegh Radford, indicated that the monks’ story might not have been that far-fetched, and that there was indeed a person of great import from the correct period buried in the graveyard just south of the Lady Chapel.

As with all things in Glastonbury, belief is always a part of the great equation.

There are other buildings associated with the abbey too, including the Abbot’s Kitchen where the Benedictine brothers would have prepared meals, and the Abbey Barn which is now home to the Somerset Rural Life Museum.

The site is lovely and inspiring. Tradition on the abbey grounds goes back ages to the very roots of Christianity in Britain and beyond, and this Christian presence comes as a surprise to the Romans who find themselves in Ynis Wytrin in Isle of the Blessed.

As I would sit on a bench, listening to the birds and the breeze, gazing upon the ruins, I would imagine St. Joseph arriving with his followers and picking out the spot for that first chapel. Perhaps they had something in common with the druids and priestesses of the goddess who might have already been there? Perhaps a common yearning for peace and truth?

It is sad that Henry VIII robbed us of the physical beauty of Glastonbury Abbey in the great Dissolution. The last abbot was dragged to the top of the Tor and beheaded by the King’s henchman, Cromwell.

For this place to function peacefully and unmolested from its earliest time, through Saxon incursions and Norman invasions, speaks to its agreed importance over the ages.

The majesty of this place may lie in ruins now, but its spirit and mystery certainly remain intact.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post on Glastonbury and The World of Isle of the Blessed as much as I enjoyed researching, revisiting, and writing about it in the novel. It was especially inspiring to write a story set in a place people of various beliefs lived together, and then to send my Roman protagonist into their midst.

What would a Roman think of a place where pagans and Christians, including Druids, lived together in peace and harmony?

Well…to learn that, you will have to read the book.

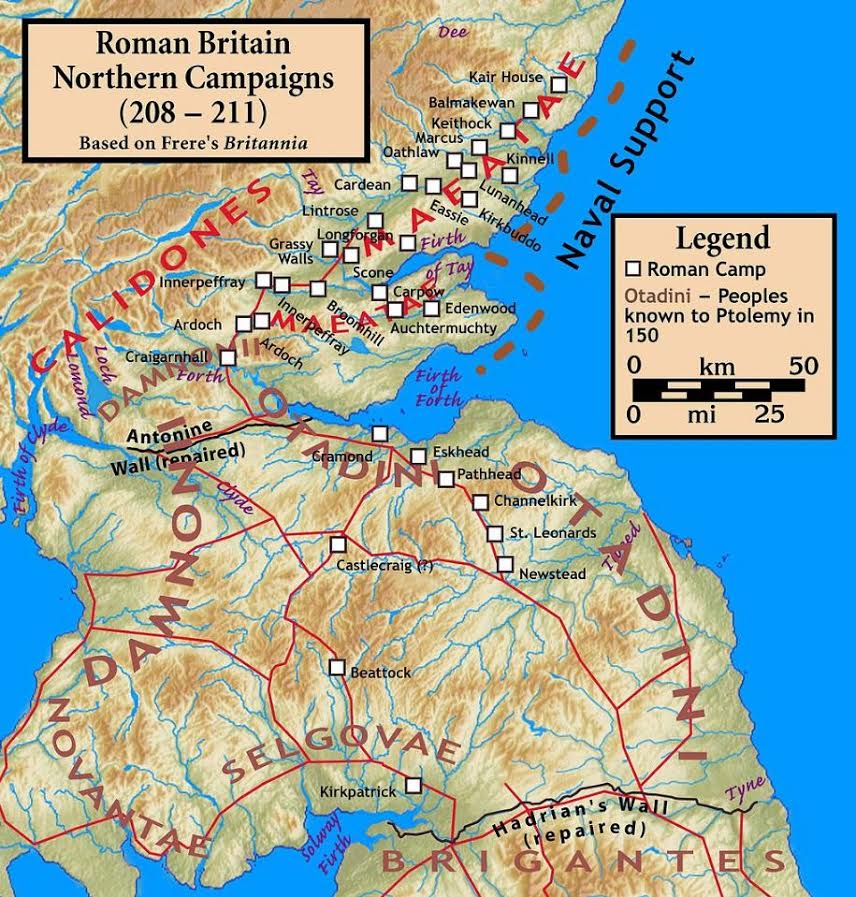

Part IV – The Court of Severus in Eburacum

In Part IV, we will be meeting some of the main players in the story, the members of Septimius Severus’ imperial court in Eburacum (modern York) when he spent three years there during the Caledonian campaign. Fans of the series will already be familiar with some, but others will be new, but no less interesting or important to this part of the story.

During the Caledonian campaign, Septimius Severus moved much of his government to Eburacum, the provincial capital of Britannia Inferior, the northern half of the province.

His entourage would have included not only his wife, sons, and other family members, but also an army of slaves, civil servants and more.

With the court moving to Eburacum for over three years, the city would have been bustling with activity. The markets would have been full with merchants and suppliers coming from around the Empire to provide for the great influx of civilians as well as the many thousands of auxiliary troops who came to Caledonia in addition to the legions that were already posted there.

Like any imperial court, however, there were camps with different intentions and interests working in the background. The glens of Scotland were not the only battlefields, and the period of Severus’ rule, perhaps especially during the Caledonian campaign, was a crucial time for the Empire.

So who were the main players at the imperial court, and where did their loyalties lie?

Severus had been ‘dying’ for years, but now, it seemed, the end was near, and the vultures were circling.

First, let us look at the family of Severus himself.

The Severans were a very interesting family and not without their tales of violence and greed and uniqueness of character. The period is not marked by something so brutal (not yet!) as the psychotic reign of Caligula, but there are certainly many more dimensions. It is a time of militarism, of a weakened Senate, a time of spymasters in various camps. It is a time marked by the rise of lower classes, the presence of powerful women and, over it all, a blanket of religious superstition at the highest levels. Many believe that it is this period in Rome’s history that marks the true beginning of the end of the Roman Empire.

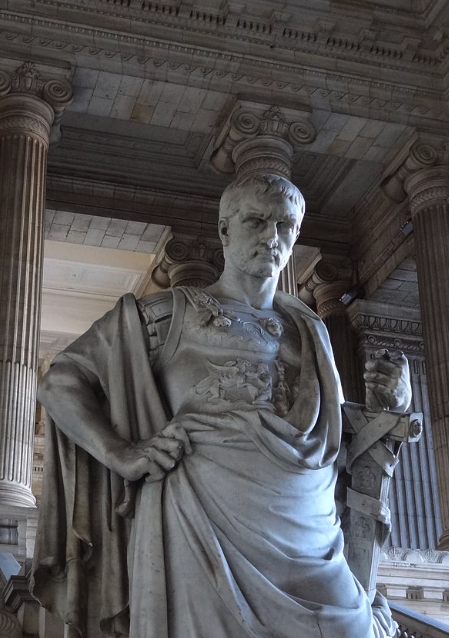

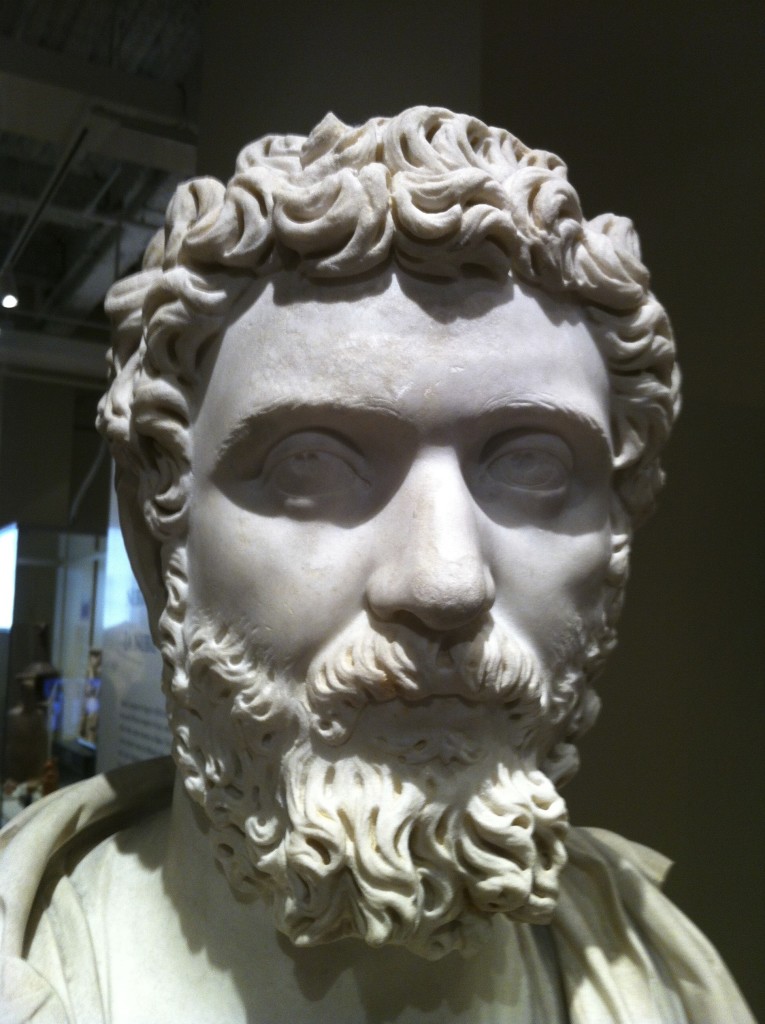

In writing the Eagles and Dragons series, it has become obvious that Septimius Severus (A.D. 193-211) was, perhaps, one of the better emperors in Rome’s history. Sure, he was not Antoninus Pius (few were), but he was far better than say, Tiberius.

He was the son of an Equestrian from Leptis Magna in North Africa. When Commodus was killed in A.D. 192, Severus was governor of Pannonia. When the Praetorians decided to auction the imperial seat a short time later, Severus’ legions declared him Emperor. He subsequently defeated his two opponents who had also declared themselves Emperor: Clodius Albinus and Pescennius Niger. A purge of his opponents’ followers in the Senate and Rome made Severus sole ruler of the largest empire in the world.

Septimius Severus was a martial emperor, the army was his power and he knew how to use it, how to keep the legions loyal and happy. During his reign, he increased troops’ pay and in a radical move, allowed soldiers to get married. Severus was good to his troops, his Pannonian Legions and victorious Parthian veterans, some of whom fought for him in Caledonia. He promoted equestrians to ranks previously reserved for aristocrats and lower ranks to equestrian status. There was a lot of mobility within the rank system at the time due to Severus ‘democratization’ of the army. Remember, this was an emperor who favoured his troops, especially those who distinguished themselves. However, as Lucius Metellus Anguis discovers in Isle of the Blessed, there are prices to be paid. No favour is free, and being close to the imperial court can be perilous.

One of the most interesting characters of the period is Empress Julia Domna. She appears as one of the strongest women in Rome’s history, an equal partner in power with her husband who heeded her advice but also respected her. Julia Domna was the first of the so-called ‘Syrian women’, hailing from Antioch where her father had been the respected high priest of Baal at Emesa (Homs in modern Syria).

Julia Domna was also highly intelligent, known as a philosopher, and had a group of leading scholars and rhetoricians about her. They came from around the Empire to be a part of her circle, to win commissions from her. Her strength also bought her a great many enemies, including the previous Praetorian Prefect and kinsman to Severus, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus. In Caledonia however, years after the death of Plautianus, with her husband’s health deteriorating rapidly, she must have worried a great deal about the dual succession of their sons, Caracalla and Geta, both of whom brought a tenseness to the court.

By all accounts Caracalla and Geta, Severus’ heirs, were both at odds much of the time. The two brothers seem to have tolerated each other’s presence and competed fiercely back in Rome, even in the hippodrome where at one point they raced each other so aggressively on their chariots that they ended up with several broken bones, almost leaving their father without a successor.

Caracalla seems to have been the favourite of the empress, though in later years Julia Domna does come to Geta’s defence, however much in vain.

One of the main reasons the sources give for the Caledonian campaign was that Septimius Severus believed it would be good for his sons, a way to teach them, give them focus, and prepare them to succeed him together. If anything, however, the angry chasm between the brothers grew worse the more their father’s light faded.

Caracalla, the older of the two brothers and about twenty-two at the time of the campaign, was the more martial of the pair. While Geta was appointed to administer the province from Eburacum, Caracalla went north to fight alongside the troops.

Did resentment build in the young Caesar as he fought, away from the court? Suspicion? Paranoia? Perhaps it was all of that and more? During the first phase of the Caledonian campaign, when Severus was about to agree to peace with Argentocoxus, the Caledonian leader, it is said that Caracalla nearly murdered his father in front of everyone, an episode that plays out in the previous novel, Warriors of Epona.

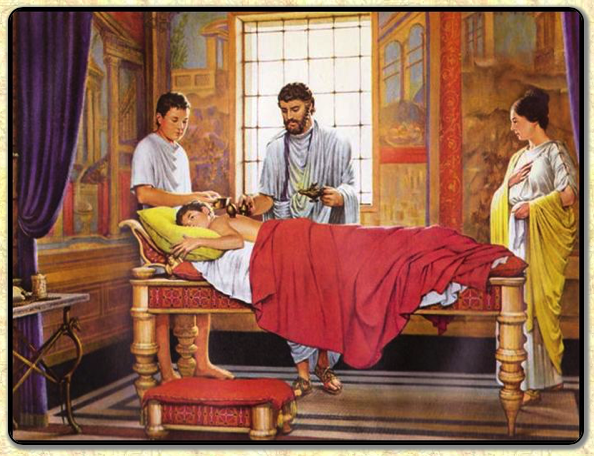

Caracalla was eager for the imperial throne, so much so that, as Herodian tell us, “he tried to persuade the physicians to harm the old man in their treatments so that he would be rid of him more quickly.”

And what of Geta, Severus’ younger son and heir?

He seems to have been entrusted with much as far as the administration of Britannia during the Caledonian campaign, so he must have been skilled to some extent. However, from what little we know of him, he was not the survivor that his brother was, and most likely lacked the ambition that was needed in the imperial court.

He was respected by people at court and by the army, but this was perhaps due more to his parentage and position than his actions over the course of his short life.

Whatever impact Geta had over the years, perhaps the most prominent was his ability to anger his brother by way of his mere existence.

One of the main players at the imperial court was Aemilius Papinianus, or ‘Papinian’ (A.D. 150-212), Prefect of the Praetorian Guard.

Papinianus is a fascinating man, a man of intelligence who was thrust, perhaps unwillingly, into one of the most powerful and perilous positions in the Roman Empire.

After the death of Gaius Fulvius Plautianus in A.D. 205, as told in Killing the Hydra, Severus appointed Papinianus as prefect of the guard. Before that, he had been a brilliant jurist (lawyer), legal expert, and had served as Severus’ main secretary. He was Syrian, and it seems likely that he was a cousin of the empress, Julia Domna. Perhaps that is why he was so trusted.

Papinianus, in his day, wrote many legal texts and was a great believer in the equity of the law. But what must he have thought to see the risk of all that Severus built over the years – with his advice – turning to ash after the succession of Caracalla and Geta?

It must have been dark days for the reluctant Praetorian Prefect.

Lurking in the shadows of Papinianus was his long-time apprentice and fellow jurist, Domitius Ulpianus, or ‘Ulpian’ (A.D. 170-223).

It seems that Ulpianus was also a brilliant lawyer who served as a secretary under Severus (beneath Papinianus), and then became Papinianus’ right hand when the latter was made Praetorian Prefect.

Interestingly, Ulpianus’ writings were very influential on Roman law and later, on the laws of Medieval Europe.

But what must he have thought constantly playing second to Papinianus? Did the apprentice ever feel jealous of the master, or try to outdo him? We don’t know for certain, but what we do know is that he survived the tough years ahead, and so he must have been close to Caracalla. In fact, Ulpianus went on to become sole Praetorian Prefect in A.D. 223 under Emperor Severus Alexander. He must have been a survivor.

There are two other men who played a very prominent role at the imperial court, who had the emperor and empress’ utmost trust, but who had also incurred the wrath of Caracalla.

Euodus, was the long-time tutor of Caracalla and Geta, and was still with the family when they went north during the Caledonian campaign. It seems that life was easier when the young caesars were smaller, but as the years went by and the animosity between them grew worse, Euodus’ job was more to try and nurture harmony between the brothers, something he evidently failed at.

This man may have felt he had much influence at court, and perhaps he did. But his constant attentions, his preachings perhaps, would prove to be more of an aggravation to Caracalla. Euodus would pay for it.

Likewise, Castor, who was Septimius Severus’ most trusted chamberlain, had a prominent role at court. He was a freedman of Severus’, elevated from a lowly rank to having the emperor’s ear, and his confidence, on a daily basis.

It is said that Castor was one of the imperial court members who most annoyed Caracalla. He was there at every turn, even when Severus reprimanded his son for attempting to kill him in front of the Caledonii at the end of the first campaign.

As Cassius Dio tell us, both Castor and Euodus did not fare well when Severus finally passed.

There were others who played a crucial role in the imperial court and would have been present at Eburacum during Severus’ time there.

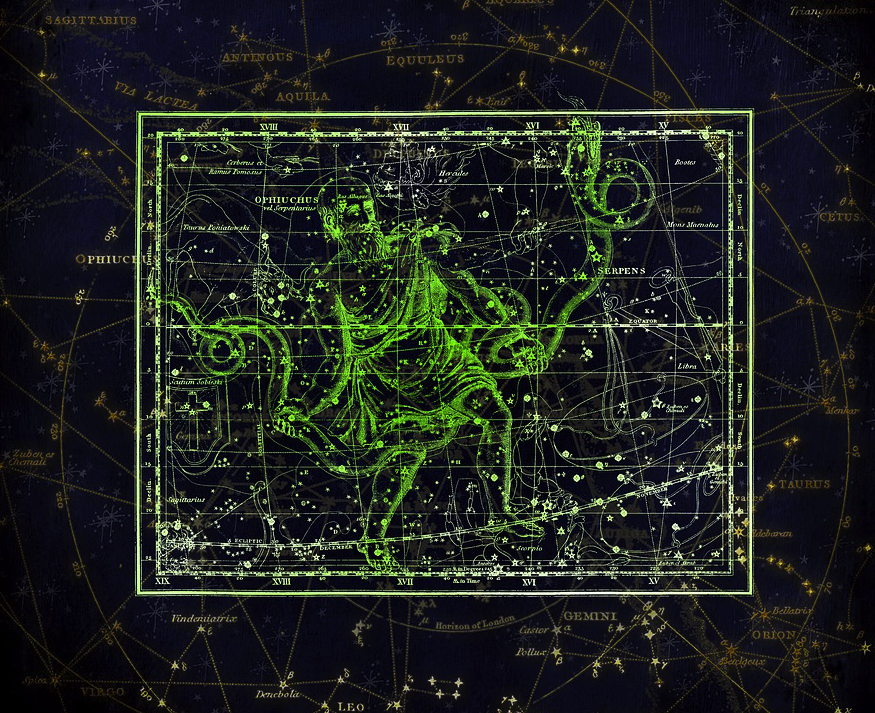

As almost fanatical believers in astrology, Septimius Severus and Julia Domna would have had their primary astrologer, possibly named Artemidoros, with them at all times. He would have done daily readings for them, advised on any action, civic, personal, or military, and was probably the one who determined the date of Severus’ death before they even left Rome.

The sources say little to nothing about him, but his role would have been an important one, his influence upon the emperor and empress great.

As someone who would have been ill for many years, Septimius Severus would have required medical attention on a daily basis, especially at the end. His physicians would have been there, at the heart of imperial politics, hearing and seeing much, including Caracalla’s aforementioned request to speed his father’s passing.

These doctors, who had refused Caracalla’s request (threat?), likely grew extremely wary as their patient’s health deteriorated more by the day in the British climate.

To this point, we’ve discussed the people whom we know to have been present at the imperial court. In truth, however, there would have been many hundreds (thousands?) who were a part of the imperial machine and civil service who were present in Eburacum. After all, the Empire was being administered from there during that time.

There are also some other key players who may have been present.

It is quite possible that Julia Domna’s sister, Julia Maesa, may have been present. After her sister, Julia Maesa was perhaps one of the most influential of the ‘Syrian Woman’. She and her daughters, Julia Soaemias Bassiana and Julia Avita Mamaea (mother of later Emperor Severus Alexander) would be extremely influential in the years to come.

It would not be surprising if Julia Maesa were present at court, close to the heart of things. She was apparently close to Caracalla too, and this would have protected her and her daughters. She survived until A.D. 226.

With much of the government following the emperor, one has to wonder if there were not also a certain number of senators present in Eburacum as well.

If so, it is possible that Cassius Dio was there. As the primary, contemporary source for the reign of Septimius Severus, it would not be surprising if he were present in Britannia for at least a portion of the campaign.

Then there is Caracalla’s wife, Plautilla, and her brother Plautius. Were they present? Or did Caracalla want to keep her as far from him as possible, as it was said that she was ever an annoyance to him in previous years.

If the names of Plautilla and Plautius are somewhat familiar to you, it may be that that is because they are the children of Gaius Fulvius Plautianus, the traitorous Praetorian Prefect who was dispatched by Caracalla and others in a plot in A.D. 205, with Julia Domna no doubt working toward that end in the background.

As for his wife and brother-in-law, Cassius Dio said that Caracalla had them killed when to took power, but whether it was immediately, or upon his return to Rome is not stated.

Another person who may have been in Eburacum for much of the time, and who may have found his work partially hi-jacked by the presence of the imperial family and the administrations of Geta, was Gaius Junius Faustinus Postumianus. He was the provincial governor of Britannia Superior, based in Londinium.

Faustinus was an officer in the army previously, before being appointed governor. What did he think about the presence of the imperial court in Britannia, or the waging of war at the borders of his province? No doubt the situation brought him many benefits, but also many headaches, especially when Severus passed from the world.

Of one thing we can be certain, and that is that an imperial court was not a place for the faint of heart.

Who survived, and who fell? Did being close to Severus’ sun mean you would get burned, or thrive?

For a writer of historical fiction, these are interesting questions to be explored with different answers for each player in the drama.

If anything, life at the court of Severus in Eburacum would have been anything but dull, despite the fact that they were on the virtual edge of the Empire.

Part V – The Death of an Emperor

Severus, seeing that his sons were changing their mode of life and that the legions were becoming enervated by idleness, made a campaign against Britain [Caledonia], though he knew that he should not return…

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, 11-1)

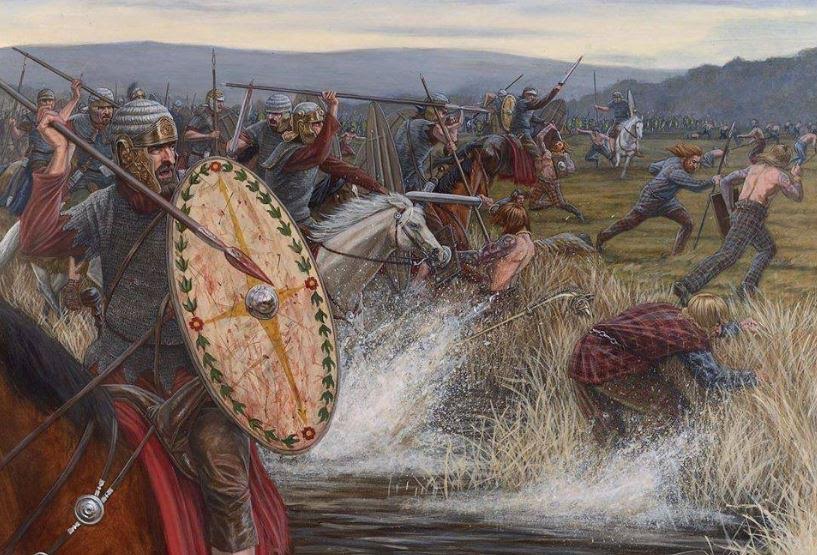

In Warriors of Epona (Eagles and Dragons, Book III), Septimius Severus and his sons, Caracalla and Geta, arrive in Britannia for the invasion of Caledonia, and the sources tell us that this was partially to occupy the two sons who were running rampant in Rome after the execution of the Praetorian Prefect, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus. You can read more about the invasion of Caledonia HERE.

However, Severus had been ill for many years, mainly from gout, and perhaps arthritis. But he was a tough specimen, a man who had come out the victor in the previous civil war against Pescennius Niger and Clodius Albinus, and then as emperor had been victorious against the Parthian Empire. After the civil war, Severus brought a period of strength and stability to the Empire that saw its borders at their greatest extent and his power almost absolute, due to the strength and loyalty of the army.

One interesting fact about Septimius Severus and his supremely intelligent empress, Julia Domna, was that they were great believers in astrology and the messages the gods inscribed on the stars regarding their fates. Their astrologer was consulted in all things and went wherever they went.

It is for this reason, it is believed, that when the emperor set out for Caledonia, he knew that he would not see Rome or Leptis Magna, his north African home, again.

He knew this chiefly from the stars under which he had been born, for he had caused them to be painted on the ceilings of the rooms in the place where he was won’t to hold court, so that they were visible to all… He knew his fate also by what he had heard from the seers; for a thunderbolt had struck a statue of his which stood near the gates through which he was intending to march out and looked toward the road leading to his destination, and it had erased three letters from his name. For this reason, as the seers made clear, he did not return, but died in the third year. He took along with him an immense amount of money.

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, 11-1)

The Caledonian campaign began in A.D. 208. About three years later, Emperor Septimius Severus did indeed die at Eburacum (modern York) on February 4th, A.D. 211.

It seems the seers and astrologers had been correct.

During the Caledonian campaign, Eburacum had been the administrative capital for the imperial court. Severus’ son, Geta took care of administration, while Caracalla and his father carried on with military actions against the Caledonians and Maeatae in the North.

However, due to Severus’ ill health, he was forced to return to Eburacum to await the arrival of those stars under which he knew he was to expire.

Herodian, the other historian for the period, gives us his account:

Now a more serious illness attacked the aged emperor and forced him to remain in his quarters; he undertook, however, to send his son out to direct the campaign. Caracalla, however, paid little attention to the war, but rather attempted to gain control of the army. Trying to persuade the soldiers to look to him alone for orders, he courted sole rule in every possible way, including slanderous attacks upon his brother. Considering his father, who had been ill for a long time and slow to die, a burdensome nuisance, he tried to persuade the physicians to harm the old man in their treatments so that he could be rid of him more quickly. After a short time, however, Severus died, succumbing chiefly to grief, after having achieved greater glory in military affairs than any of the emperors who had preceded him. No emperor before Severus had won such outstanding victories either in civil wars against political rivals or in foreign wars against barbarians. Thus Severus died after ruling for eighteen years, and was succeeded by his young sons, to whom he left an invincible army and more money than any emperor had ever left his successors.

(Herodian, History of the Empire, XV 1)

The death of Septimius Severus is a crucial moment in Isle of the Blessed, and indeed in the entire Eagles and Dragons series.

I have been writing about this fascinating emperor for a long time, since Parthia, and then, as the stars loomed above him, as his day of death appeared on the horizon, it was time to explore his thinking toward the end.

How difficult it must have been for such a strong individual to face his end? After winning, creating, and ruling a vast, thriving empire, how could he deal with saying goodbye to it all?

It was a privilege to write about it in Isle of the Blessed.

The research into Severus’ death was also fascinating. Cassius Dio gives some details:

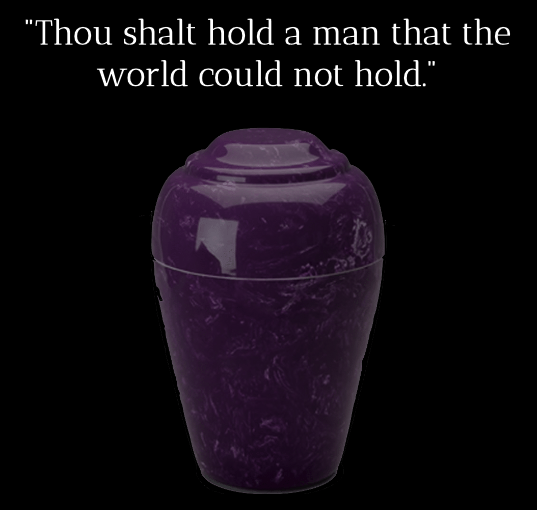

…his body, arrayed in military garb, was placed upon a pyre, and as a mark of honour the soldiers and his sons ran about it; and as for the soldiers’ gifts, those who had things at hand to offer as gifts threw them upon it, and his sons applied the fire. Afterwards his bones were put in an urn of purple stone, carried to Rome, and deposited in the tomb of the Antonines. It is said that Severus sent for the urn shortly before his death, and after feeling of it, remarked: “Thou shalt hold a man that the world could not hold.”

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, 15, 2)

One can imagine Severus, staring at the stars he had had painted everywhere, and at the stone urn that would hold his remains, but my research into the death of this great emperor of Rome led me to something even more fascinating.

The funeral pyre of Septimius Severus was said to have been the largest pyre ever to be seen in Britannia.

But what did such a thing look like? Where in Eburacum could it have been located?

Numismatology, the study of coinage, has been extremely useful to me in my research into the Severans over the course of this series of novels, and once again, it proved extremely useful.

When looking for any information I could find on the death of Severus, I came across an image of a coin minted by Caracalla after the death of his father. It was perfect, for this coin depicted exactly what I was looking for…

On this coin is depicted the funeral pyre of Septimius Severus himself. It provided me with the information I needed to accurately describe this event.

Serendipity does indeed happen in research too!

The other question was the location of the pyre. Where could it have been located? Of course, the pyre would have had to be outside the city walls of Eburacum. But the ustrinum, the burning place, for such a large pyre would have to be far removed from the city.

Here too, the stars aligned for my research.

In modern York (ancient Eburacum) there is a place called ‘Severus Hill’ which is a large hill (now topped by a water tower) in an otherwise flat landscape that some historians believe was created by glacial shiftings millions of years ago.

However, I discovered that there is another theory about Severus Hill that the feature was not created by glaciers, but rather that it is the overgrown remains of Septimius Severus’ giant funeral pyre.

I thought about this, about the distance from the ancient city walls (about 2 miles) and the toponymics of the place (place name). Whether the theory is absolutely true or not, it fit well with the story I was trying to tell.

It is wonderful when a plan, erm…plot, comes together!

Thus, my time with Septimius Severus, one of Rome’s great emperors, has come to an end. I will miss him.

He was not perfect, to be sure, but his life and actions have been fascinating to explore. He had great successes, but he also had failures, and perhaps his greatest failure was to entrust the empire he had built to his two sons, Caracalla and Geta.

Severus had, at one point, criticized Marcus Aurelius for making Commodus his heir, but he in turn had made the same mistake.

And the Empire would pay for it.

Still, Septimius Severus was an emperor until the very end, when his stars flickered and faded. His final words, as Cassius Dio tells us, were: “Come, give it here, if we have anything to do.”

Part VI – Mass Murder in Roman York

After his father’s death, Caracalla seized control and immediately began to murder everyone in the court; he killed the physicians who had refused to obey his orders to hasten the old man’s death and also murdered those men who had reared his brother and himself because they persisted in urging him to live at peace with Geta. He did not spare any of the men who had attended his father or were held in esteem by him.

(Herodian, History of the Empire, XV-4)

Thus began the reign of Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus Augustus, the emperor more commonly known as Caracalla.

Welcome back to The World of Isle of the Blessed, the blog series in which we look at the research that went into the creation of the latest Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy novel.

In Part V, we looked at the death of Emperor Septimius Severus in York. If you missed that post, you can read it HERE.

In Part VI we are going to explore the immediate aftermath of Severus’ death, and how a mysterious archaeological discovery gives some interesting clues about the bloody beginning of Caracalla’s reign.

Septimius Severus and Caracalla (painting by Jean-Baptiste Greuze; Department of Paintings of the Louvre)

It could be argued that the death of Septimius Severus in York (Roman Eburacum) in A.D. 211 was one of the most pivotal moments in Rome’s history, that it was perhaps the beginning of the end for the Empire.

Severus had always been a strong leader who had decisively won out over his opponents in the civil war, who had conquered the Parthian Empire, and perhaps most importantly, had nurtured the loyalty of the legions.

As Cassius Dio tells us, one of the final pieces of advice to both of his sons was to “be harmonious, enrich the soldiers, and scorn all other men.”

But harmony between his sons and heirs, Caracalla and Geta, was something that would never come to be. As explored in Killing the Hydra (Eagles and Dragons Book II), after the death of Plautianus, Severus’ previous, traitorous Praetorian prefect, the two brothers were constantly at odds, running amok in Rome.

That was one of the reasons the sources give for the Caledonian campaign, that it was to give his sons a sense of purpose.

His belief in his sons, especially in Caracalla, might have been Severus’ fatal flaw when it came to the health of the Empire. Dio tells us “he had often blamed Marcus [Aurelius] for not putting Commodus quietly out of the way and that he had himself often threatened to act thus toward his son [Caracalla]”.

But Severus erred and made the same mistake as Marcus Aurelius, and set his son upon the imperial throne. Only this time, there were two heirs, and if one thing is certain, imperial power was never easily shared.

When Septimius Severus finally passed away in Eburacum, (Roman York) on February, A.D. 211, Caracalla made his bid to secure power immediately.

As have other rulers in Rome’s history, he began by eliminating his perceived enemies, those who posed an immediate threat.

This did not include his brother Geta at first, for Geta was also well-loved by the men of the legions as Severus’ son, and Caracalla needed the legions’ loyalty.

Others were not so fortunate.

As Herodian tells us in the quote above, Caracalla began to “murder everyone in the court”.

But how and where did he do this?

In the early 2000s, a gruesome discovery beneath a patio in York hints at what might have happened.

What this archaeological discover entailed aligns well with what we are told of Caracalla’s bloody start to his reign, and hints at the madness or paranoia that already had a hold on the young emperor.

As it turns out, the discovery in York entailed the burials of over 30 male skeletons, all of them between the ages of twenty and forty.

The strange thing about these skeletons was that they were all decapitated…executed. And they date to the beginning of Caracalla’s reign.

The heads of the bodies were places in strange positions – some by the feet or between the legs and some face down. There are even two skeletons in which the heads were exchanged, the one put with the other.

Ancient Romans took death and burial seriously, but in this instance there is little respect shown to the skeletons.

From the forensic evidence, experts believe that these men were executed by beheading.

Some of the bones display horrific injuries too. A few show a single, clean cut through the vertebrae of the neck, but others show a brutal end with one skeleton displaying eleven separate cuts to the neck on all sides, plus a massive head trauma.

So, who were these men that Caracalla would strike so brutally at them?

The theories vary, but it seems likely that most of them were Praetorians who had been loyal, not only to his father, but to Papinianus, the Praetorian Prefect. These were men Caracalla felt he did not have their loyalty. But there were possibly others among the slain.

It is quite possible that among the dead are the remains of the doctors who refused to help speed the emperor’s passing when requested by Caracalla. Also, Severus’ loyal freedman, Castor, is a possible victim, for he was often at odds with the young Caesar and had Severus’ confidence. Another who had helped to rear Caracalla and Geta, and who is said to have often annoyed the former, was their tutor, Euodus. Was he also among the decapitated dead?

One of the decapitated bodies found as if thrown unceremoniously into the ‘grave’ (photo: York Archaeological Trust)

Whoever the victims of this massacre in Roman York were, they had incurred Caracalla’s anger in some way, and he made them pay for it before dumping their mangled corpses in a cemetery outside the walls of the city.

In Isle of the Blessed, this horrific event is one of the more grisly episodes in a history that, quite frankly, you just can’t make up.

Often, history is unbelievable, and when turning it into fiction, the stakes have to be raised.

So, what happens to the protagonist, Lucius Metellus Anguis, during Caracalla’s rampage in Isle of the Blessed?

You have to read the story to experience it for yourself.

To learn more about the Severan invasion of Scotland as well as the archaeological discovery of the decapitated bodies at York, be sure to watch the Timewatch documentary below.