Salvete Readers and Romanophiles!

Welcome back to The World of Sincerity is a Goddess, the blog series in which we share the research for our latest novel, Sincerity is a Goddess: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome.

If you missed the third post on humour and comedy in ancient Rome, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In part four of this blog series, we’re going to be looking at games, or ludi, in ancient Rome, and then specifically at the games in the book, the Ludi Apollinares, the Games of Apollo.

Let’s get started

Ludi, or public games, were an important occurrence on the Roman calendar. Not only did they give the gods their due through religious rites and rituals, but they also gave the people a chance to unwind and enjoy themselves.

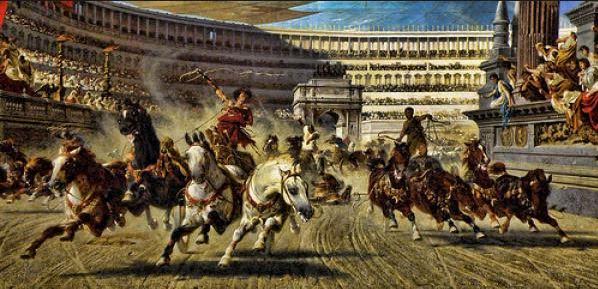

Apart from the often very specific religious rituals dedicated to whichever deity the games honoured, there were often also processions, chariot races and theatrical performances. Early on, most ludi did not include gladiatorial combat as these were reserved for funeral games alone, or ludi funebris.

Not only did games in ancient Rome provide some much needed distraction for the people from the dangers of the day, they were also a way for politicians to buy votes. The reason for this is that, though games received some funding from the state, most of the cost of ludi were paid for by wealthy citizens.

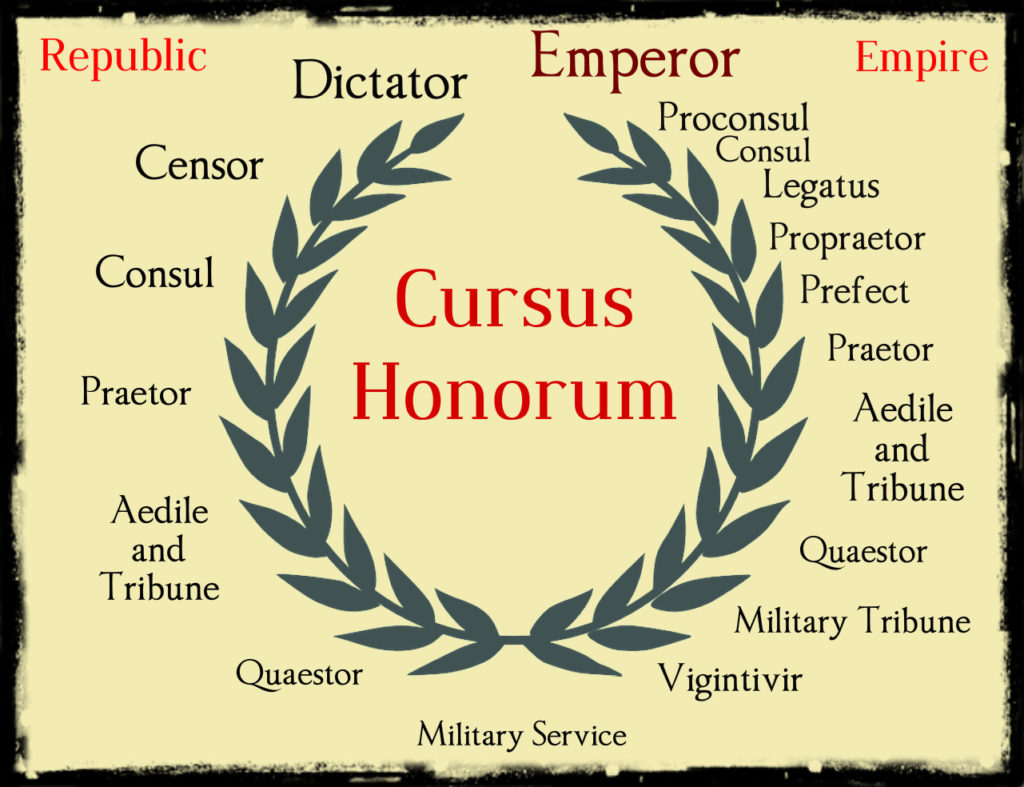

General representation of the steps along the cursus honorum during the Republican and Imperial periods.

When it came to positions on the Cursus Honorum of Roman politics, the responsibility of putting on, and funding, games most often lay with the aediles, those four politicians who were at least 37 years old and were charged with looking after the interests of the city of Rome. They looked after temples, markets, streets, squares, brothels, baths, and the water supply. Very important jobs indeed.

The aediles – and sometimes praetors – were also to ensure the success of the public games.

As mentioned, the Roman state did provide a very basic operating budget for games. For example, the Ludi Romani in honour of Jupiter, held from September 5-19, at one point received 760,000 sestercii, and the Ludi Plebii, held from November 4-17, received 600,000 sestercii. The rest – which was the majority of the expense – was paid for by the aedile or praetor sponsoring the games.

These games were extremely important events on the Roman calendar, a time when the lower classes could let go and enjoy feasts and entertainments for free, and when the upper classes could see and be seen.

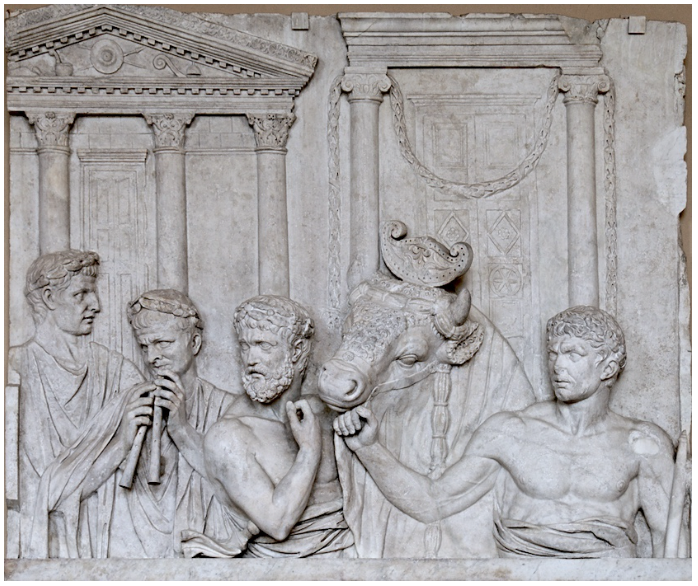

Preparation for a Sacrifice

Different ludi were dedicated to individual deities, and so religious ceremonies, often with very specific sacrifices, were also a part of the games.

Games were, first and foremost, considered sacred acts.

Games were also founded to commemorate victories, and this became a point of pride for rulers and politicians. An example of this is in the Emperor Augustus’ Res Gestae, or ‘Things Done’:

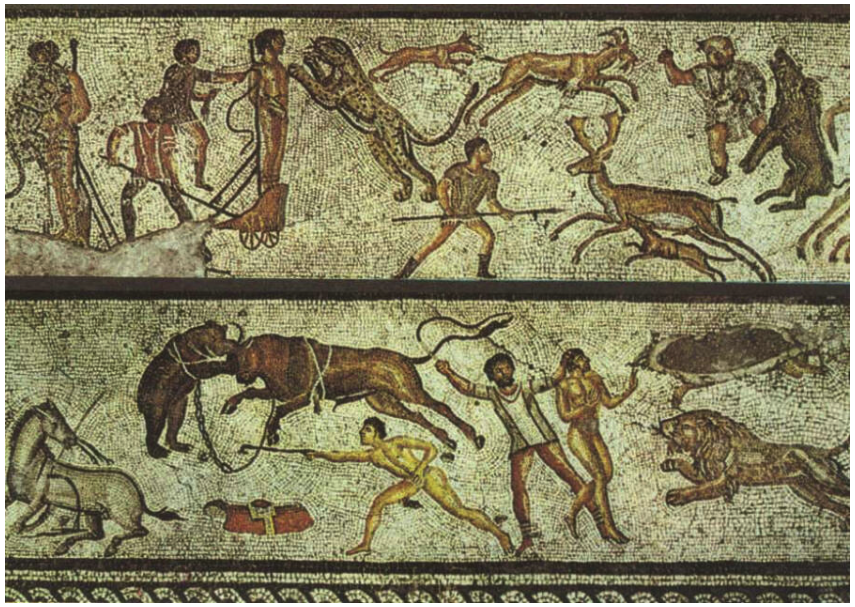

Three times I held gladiatorial spectacle in my own name and five times in the names of my sons or grandsons; in which spectacles some ten-thousand men took part in combat. Twice in my own name and a third time in the name of my grandson, I provided a public display of athletes summoned from all parts. I held games four times in my own name and twenty-three times on behalf of other magistrates… I have provided public spectacles of the hunting of wild beasts twenty-six times in my own name or that of my sons and grandsons, in the Circus or the Forum or the amphitheatres in which three-thousand five-hundred beasts have been killed.

(Res Gestae XXII)

Today, if someone boasted of so much killing, they would be considered a human abomination in most countries, but in the world of ancient Rome, acts such as these were considered extremely generous, gifts for the people, actions which helped to secure the favour of the people.

If the mob of Rome was happy, they did not cause trouble.

A Venatio – A Roman Animal Hunt

There were different types of ludi as well. There could be ludi votivi, which were held in fulfillment of a vow, or ludi funebris, which were funeral games paid for by a dead person’s family. Public ludi, as we have mentioned, were paid for by the state and the aediles or praetors.

The oldest games are said to be the Ludi Romani which were dedicated to Jupiter and are thought to have been held since 509 B.C. when the temple of Jupiter was dedicated on the Capitol of Rome.

Other games that dotted the Roman calendar were the Ludi Cereri held in honour of Ceres from about 202 B.C., the Ludi Plebii also held for Jupiter from about 216 B.C., the Ludi Megalensi, held in honour of Cybele, and the Ludi Taurii, held in honour of Mars.

And then there were the Ludi Apollinares which are a part of the story of Sincerity is a Goddess.

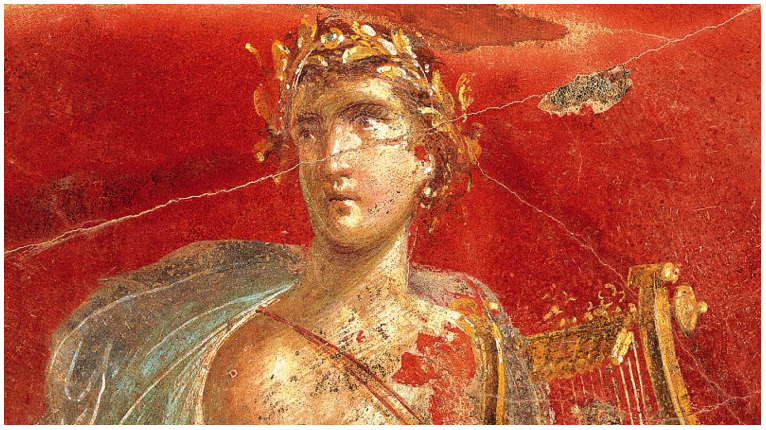

Apollo pouring a libation

The advent of the Ludi Apollinares, the Games of Apollo, are a bit different in their origin from some of the other games. They were begun in the wake of one of the worst defeats in Rome’s history, and born out of a prophecy that was found after the fact. Let me explain…

The Ludi Apollinares were first held in 212 B.C. during the second Punic War, four years after Hannibal’s crushing defeat of Rome’s legions at the battle of Cannae.

In the wake of this defeat, with Hannibal at the gates of Rome, Hannibal ante portas!, the Romans found a prophecy in the Carmina Marciana, the prophecies of the seer, Marcius. Livy, recounts this in his history of Rome…

The importance attached to one of the two predictions of Marcius, which was brought to light after the event to which it related had occurred, and the truth of which was confirmed by the event, attached credence to the other, the time of whose fulfilment had not yet arrived. In the former prophecy, the disaster at Cannae was predicted in nearly these words: “Roman of Trojan descent, fly the river Canna, lest foreigners should compel thee to fight in the plain of Diomede. But thou wilt not believe me until thou shalt have filled the plain with blood, and the river carries into the great sea, from the fruitful land, many thousands of your slain countrymen, and thy flesh becomes a prey for fishes, birds, and beasts inhabiting the earth. For thus hath Jupiter declared to me.” Those who had served in that quarter recognized the correspondence with respect to the plains of the Argive Diomede and the river Canna, as well as the defeat itself.

(Livy, The History of Rome, Book XXV, 12)

The Death of Paulus Aemilius at the Battle of Cannae (John Trumbull 1773)

The discovery of this prophecy made the Romans take action. We have to remember that this was one of the most terrifying periods in Rome’s history. Hannibal was at the gates of the city, he had defeated a far larger force in one of history’s great victories at the battle of Cannae to the south, on Italian soil.

The Romans did not want to experience such a defeat again and so the Ludi Apollinares were instituted originally as votive games for two purposes: to acquire the gods’ aid in expelling the Carthaginians from Italy, and to protect the Roman Republic from all dangers. They were, originally to be held once, but the year after, the senate passed a decree based on the proposal of the praetor, Calpurnius, that the Ludi Apollinares be held every year as circumstances allowed, i.e. with no fixed date.

In 208 B.C., after a plague in the city, the praetor, Varus, put forward a bill that the Games be held every year on the specific date of July 6th.

And so, the Ludi Apollinares became a permanent part of the Roman festival calendar.

But what did these games entail?

Luckily, another prophecy in the Carmina Marciana prescribed the specific rituals and sacrifices that should be performed to honour Apollo. Again, Livy recounts this:

The other prophecy was then read, which was more obscure, not only because future events are more uncertain than past, but also from being more perplexed in its style of composition. “Romans, if you wish to expel the enemy and the ulcer which has come from afar, I advise, that games should be vowed, which may be performed in a cheerful manner annually to Apollo; when the people shall have given a portion of money from the public coffers, that private individuals then contribute, each according to his ability. That the praetor shall preside in the celebration of these games, who holds the supreme administration of justice to the people and commons. Let the decemviri perform sacrifice with victims after the Grecian fashion. If you do these things properly you will ever rejoice, and your affairs will be more prosperous, for that deity will destroy your enemies who now, composedly, feed upon your plains.” They took one day to explain this prophecy. The next day a decree of the senate was passed, that the decemviri should inspect the books relating to the celebration of games and sacred rites in honour of Apollo. After they had been consulted, and a report made to the senate, the fathers voted, that “games should be vowed to Apollo and celebrated; and that when the games were concluded, twelve thousand asses should be given to the praetor to defray the expense of sacred ceremonies, and also two victims of the larger sort.” A second decree was passed, that “the decemviri should perform sacrifice in the Grecian mode, and with the following victims: to Apollo, with a gilded ox, and two white goats gilded; to Latona, with a gilded heifer.” When the praetor was about to celebrate the games in the Circus Maximus, he issued an order, that during the celebration of the games, the people should pay a contribution, as large as was convenient, for the service of Apollo. This is the origin of the Apollinarian games, which were vowed and celebrated in order to achieve victory, and not restoration to health, as is commonly supposed. The people viewed the spectacle in garlands; the matrons made supplications; the people in general feasted in the courts of their houses, throwing the doors open; and the day was distinguished by every description of ceremony.

(Livy, The History of Rome, Book XXV, 12)

It is truly fascinating to read this passage for it is quite specific from the amount to be spent by the state, and the specific animals with gilded horns to be offered to Apollo and Latona (i.e. Leto, his mother), and that this should be done in the Greek fashion, the ritus Graecus, that is, with the head uncovered for the sacrifice.

The prophecy also prescribes a joyful atmosphere that is pleasing to the gods in which people offer what they can, wear garlands, and dine together with the doors of their homes thrown open.

Sacrifices were central to Roman Ludi

At these first games of Apollo, most of the events took place in the Circus Maximus of Rome and included chariot races – by far Rome’s most popular pastime – animal hunts, religious processions and, most importantly to our story, theatrical performances.

Interestingly, we have a record of one of the specific plays performed in the games of 169 B.C. and that was the revenge tragedy of Thyestes who was King of Olympia and the son of Pelops and Hippodameia.

I think it is a safe assumption that though theatrical performance was originally a small part of the games of Apollo, over time, more would have been included, especially under such emperors as Nero, who saw himself as a great performer.

The Ludi Apollinares were smaller games than the Ludi Romani or Ludi Plebii. After all, they received less funding. But, they did grow in popularity and, eventually, they went from being celebrated for one day on July 13th, to being held for eight days from July 6th to 13th.

More events would have been held over this extended period, and though it was still, at heart, a religious and votive festival, the theatre played a large part in it.

Apollo

We can end on a small anecdote that I came across in my research that illustrates this and the importance of properly seeing through the required rituals.

In the second year of the games, in 211 B.C. there is a story that during a theatrical performance for the Ludi Apollinares, a cry and panic went up in the audience that Hannibal was at the gates – Hannibal ante portas!

The spectators rushed from the theatre to get their weapons and fight to defend the city. However, it turned out to be a false alarm.

When the audience members returned to the theatre, and the play that had been so harshly interrupted, they found the dancer still dancing, and the accompanying flute player still playing! It was a marathon performance for the two, and the audience cried out “All is saved!”

Hannibal did not attack the city.

I don’t know for certain if this story is true, but it is a good one!

The show must go on and, it seems, in ancient Rome, it was indeed a matter of life and death!

Thank you for reading.

Sincerity is a Goddess is now available in ebook, paperback and hardcover from all major online retailers, independent bookstores, brick and mortal chains, and your local public library.

CLICK HERE to buy a copy and get ISBN#s information for the edition of your choice.

The Etrurian Players are coming! Brace yourselves!

This is so interesting. Thanks Adam for sharing your knowledge of The Roman Empire. Hope all is well with you and your family.

You’re very welcome, Rita! Glad you enjoyed this one 🙂