Salvete, Readers and Romanophiles!

Welcome to The World of The Blood Road! In this nine-part series, we’re going to be taking a look at some of the history, people, and places that appear and provide the settings for this sixth book in the #1 best selling Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series.

If you’re a fan of the series, and don’t want any spoilers at all (such as where the story will lead you across the Empire), then you may wish to hold off until you’ve read the book.

However, if you just want to get stuck into the history and research that went into this novel, read on! We hope you enjoy it!

Part I – Caracalla: Emperor and Murderer

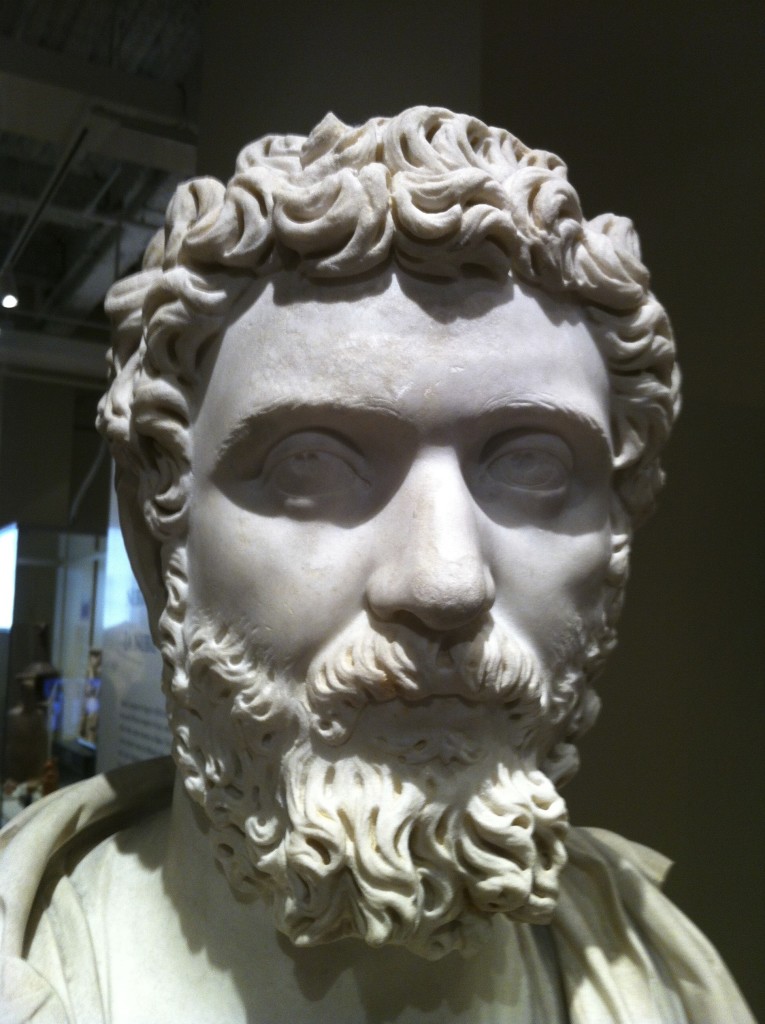

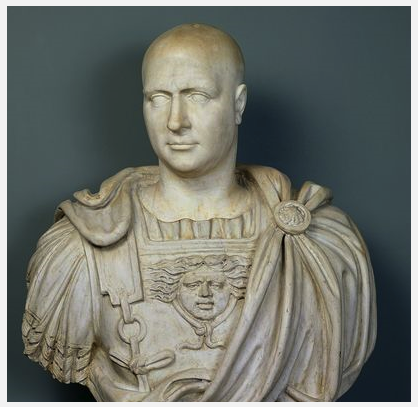

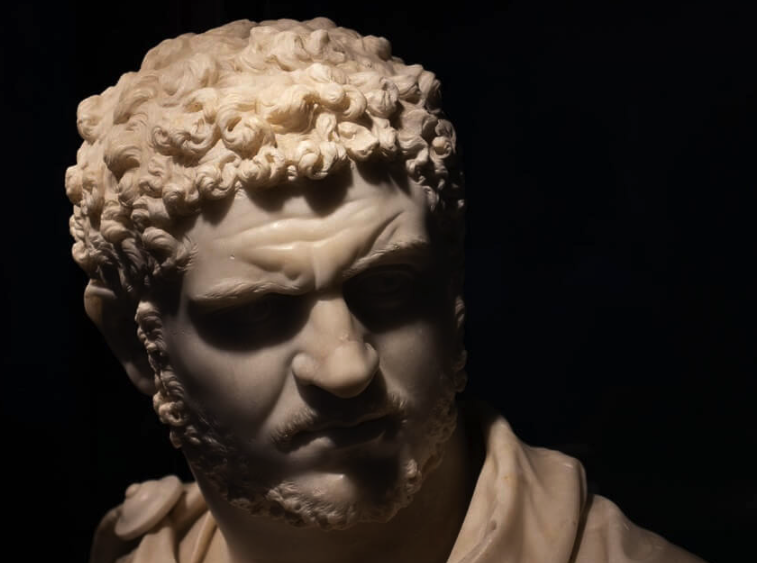

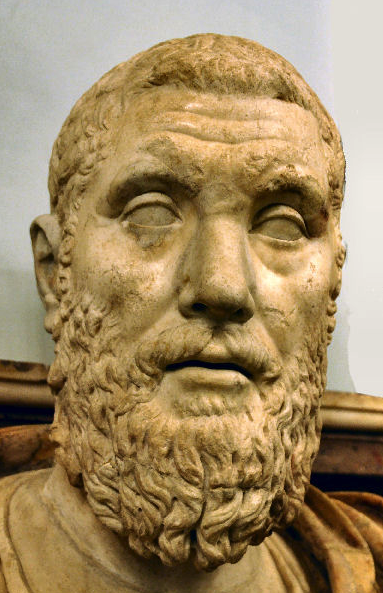

Emperor Caracalla

When we look at lists of Rome’s emperors, inevitably there are a few names that jump out at us because of their infamy and the brutality of their deeds. Emperors such as Caligula or Commodus might stand out to some. But, the beginning of the 3rd century A.D. is no less marred by the presence of another such Roman Emperor: Caracalla.

Fans of the Eagles and Dragons series will already be familiar with the bloody deeds which Caracalla may have perpetrated in Eburacum after the death of his father, Septimius Severus. If you missed the post on mass murder in Roman York, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

After the death of Severus, Caracalla and his brother, Geta, became co-emperors, and each of them hurried back to Rome separately to establish their own power at the heart of the Empire.

This tumultuous beginning to their reign is where The Blood Road begins.

Septimius Severus

It could be said that Caracalla and Geta’s father, Septimius Severus, was the only great emperor of the Severan dynasty. However, even good emperors can have major flaws and, like Marcus Aurelius before him, Severus’ greatest flaw was, perhaps, that he trusted in his sons far too much.

One theory about the Caledonian campaign is that Severus saw it as a way to force his sons to mend their troubled ways and end their squabbling. But this did not have the intended outcome. As soon as Severus died, people braced themselves for the inevitable quarrel between the two brothers. Cassius Dio describes the scene in Rome when the two emperors returned from Caledonia:

As for his own brother, Antoninus had wished to slay him even while his father was yet alive, but had been unable to do so at the time because of Severus, or later, on the march, because of the legions; for the troops felt very kindly toward the younger brother, especially as he resembled his father very closely in appearance. But when Antoninus got back to Rome, he made away with him also. The two pretended to love and commend each other, but in all that they did they were diametrically opposed, and anyone could see that something terrible was bound to result from the situation. This was foreseen even before they reached Rome. For when the senate had voted that sacrifices should be offered on behalf of their concord both to the other gods and to Concord herself, and the assistants had got ready the victim to be sacrificed to Concord and the consul had arrived to superintend the sacrifice, neither he could find them nor they him, but they spent nearly the entire night in searching for one another, so that the sacrifice could not be performed then.

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, LXXVIII-1)

Rare bust of Geta in the Louvre (Wikimedia Commons)

There was even talk of ill-omens within the city, specifically one mentioned by Cassius Dio in which “two wolves went up on the Capitol, but were chased away from there; one of them was found and slain somewhere in the Forum and the other was killed later outside the pomerium. This incident also had reference to the brothers.”

In the middle of the tense stand-off between the two brothers was their mother, Julia Domna, who was constantly seeking to reconcile her sons, just as her husband had.

Julia Domna

When, according to Herodian, the brothers devised a pretence of dividing up the Empire that their father had worked so tirelessly to unite, Julia Domna pleaded with them:

As the brothers were now completely at odds in even the most trivial matters, their mother undertook to effect a reconciliation.

And at that time they concluded that it was best to divide the empire, to avoid remaining in Rome and continuing their intrigues. Summoning the advisers appointed by their father, with their mother present too, they decided to partition the empire: Caracalla to have all Europe, and Geta all the lands lying opposite Europe, the region known as Asia.

For, they said, the two continents were separated by the Propontic Gulf as if by divine foresight. It was agreed that Caracalla establish his headquarters at Byzantium, with Geta’s at Chalcedon in Bithynia; the two stations, on opposite sides of the straits, would guard each empire and prevent any crossings at that point. They decided too that it was best that the European senators remain in Rome, and those from the Asiatic regions accompany Geta.

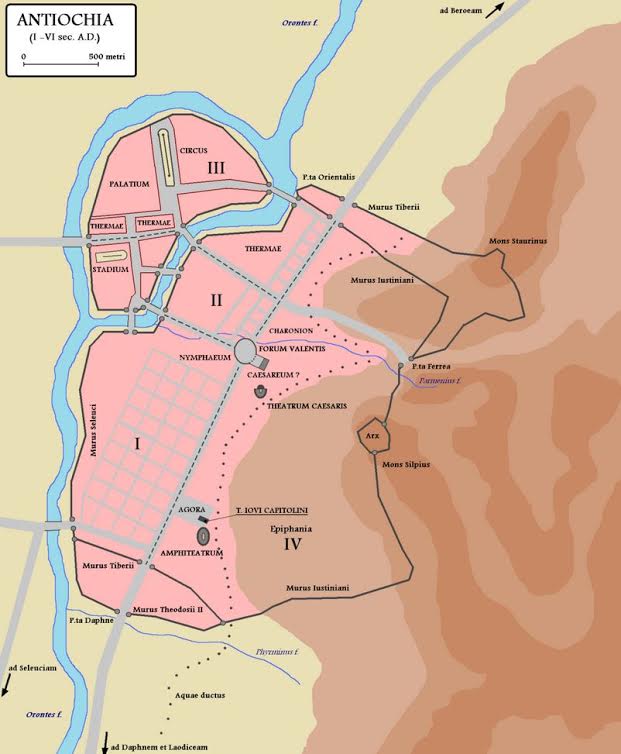

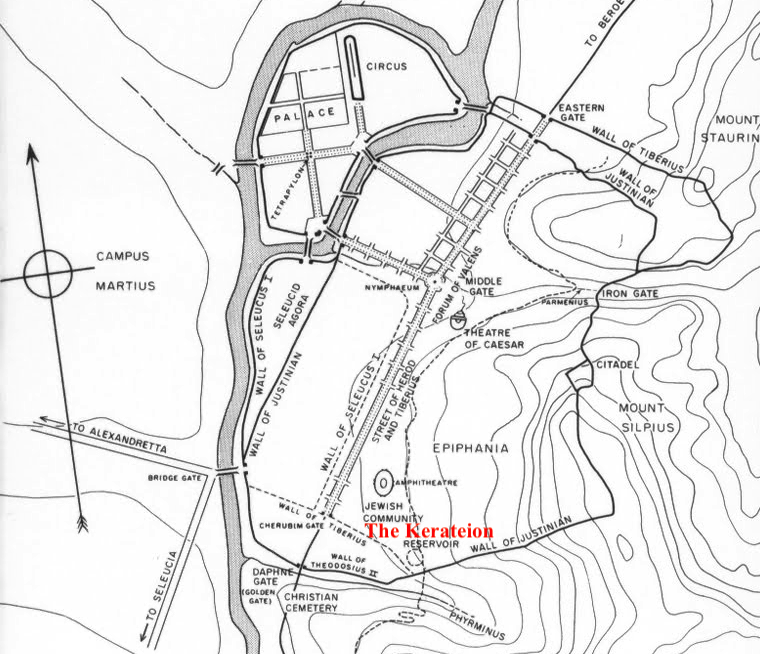

For his capital city, Geta said that either Antioch or Alexandria would be suitable, since, in his opinion, neither city was much inferior in size to Rome. Of the Southern provinces, the lands of the Moors, the Numidians, and the adjacent Libyans were given to Caracalla, and the regions east of these peoples were allotted to Geta.

While they were engaged in cleaving the empire, all the rest kept their eyes fixed on the ground, but Julia cried out: “Earth and sea, my children, you have found a way to divide, and, as you say, the Propontic Gulf separates the continents. But your mother, how would you parcel her? How am I, unhappy, wretched – how am I to be torn and ripped asunder for the pair of you? Kill me first, and after you have claimed your share, let each one perform the funeral rites for his portion. Thus would I, too, together with earth and sea, be partitioned between you.”

After saying this, amid tears and lamentations, Julia stretched out her hands and, clasping them both in her arms, tried to reconcile them. And with all pitying her, the meeting adjourned and the project was abandoned. Each youth returned to his half of the imperial palace.

(Herodian, History of the Roman Empire, 4.3)

Sadly, it seems the Goddess Concord turned her back on the situation, just as Caracalla and Geta had turned their backs on her. Rome’s ‘wolves’ were determined to destroy each other, and each was aware of plots against him. They both became obsessed and paranoid (perhaps rightly so) and as Herodian tells us: “They tried every sort of intrigue; each, for example, attempted to persuade the other’s cooks and cupbearers to administer some deadly poison. It was not easy for either one to succeed in these attempts, however: both were exceedingly careful and took many precautions. Finally, unable to endure the situation any longer and maddened by the desire for sole power, Caracalla decided to act…”

Palace of Septimius Severus, Palatine Hill, Rome (photo by Lasse Lofstrom; Trek Earth)

Throughout the history of Rome, there have been many heinous acts perpetrated by emperors, but what happened next is perhaps near the top of the list.

Frustrated by another failed attempt upon Geta’s life at Saturnalia in A.D. 211, Caracalla decided enough was enough:

Antoninus [Caracalla] induced his mother to summon them both, unattended, to her apartment, with a view to reconciling them. Thus Geta was persuaded, and went in with him; but when they were inside, some centurions, previously instructed by Antoninus, rushed in a body and struck down Geta, who at sight of them had run to his mother, hung about her neck and clung to her bosom and breasts, lamenting and crying: “Mother that didst bear me, mother that didst bear me, help! I am being murdered.” And so she, tricked in this way, saw her son perishing in the most impious fashion in her arms, and received him at his death into the very womb, as it were, whence he had been born; for she was all covered with his blood, so that she took no note of the wound she had received on her hand. But she was not permitted to mourn or weep for her son, though he had met so miserable an end before his time…she alone, the Augusta, wife of the emperor and mother of the emperors, was not permitted to shed tears even in private over so great a sorrow.

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, LXXVIII-2)

Geta Dying in his Mother’s Arms by Jacques-Augustin-Catherine Pajou, Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart, Germany (Wikimedia Commons)

Dio tells us that Caracalla ordered the centurions to murder Geta, and Herodian says that Caracalla did the deed himself. Either way, it seems that Geta bled to death in his mother’s arms.

Fratricide was highly frowned upon, and Caracalla knew that Geta had a lot of supporters among the people, the senators, and in the legions. Herodian tells us that he fled, under guard, to the Praetorian camp where he explained to the troops that he had escaped a plot against his life, and that the Gods had chosen him as sole emperor.

In gratitude for his deliverance and in return for the sole rule, he promised each soldier 2,500 denarii and increased their ration allowance by one-half. He ordered the praetorians to go immediately and take the money from the temple depositories and the treasuries. In a single day he recklessly distributed all the money which Severus had collected and hoarded from the calamities of others over a period of eighteen years.

When they heard about this vast amount of money, although they were aware of what had actually occurred, the murder having been made common knowledge by fugitives from the palace, the praetorians at once proclaimed Caracalla emperor and called Geta enemy.

(Herodian, History of the Roman Empire, 4.4)

After this bloody act, when he emerged from the protection of the Castra Praetoria with his guard, Caracalla set about securing his position as sole emperor with further acts of blood.

In a long series of proscriptions, with the legions and Praetorian Guard behind him, safely purchased with all of the funds he could muster, Caracalla set about eliminating anyone who could pose a potential threat, or even whisper a word against him:

Of the imperial freedmen and soldiers who had been with Geta he immediately put to death some twenty thousand, men and women alike, wherever in the palace any of them happened to be; and he slew various distinguished men…

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History, LXXVIII-4)

Many perished with the beginning of Caracalla’s sole rule as emperor, and one wonders if he ever lived that down. His father’s past advice about securing the loyalty of the legions was, it seemed, the only thing that saved him, at least for a time. No matter one’s station, anyone with a passing connection to Geta was slain, and the list is a lengthy one, according to Herodian:

Geta’s friends and associates were immediately butchered, together with those who lived in his half of the imperial palace. All his attendants were put to death too; not a single one was spared because of his age, not even the infants. Their bodies, after first being dragged about and subjected to every form of indignity, were placed in carts and taken out of the city; there they were piled up and burned or simply thrown in the ditch.

No one who had the slightest acquaintance with Geta was spared: athletes, charioteers, and singers and dancers of every type were killed. Everything that Geta kept around him to delight eye and ear was destroyed. Senators distinguished because of ancestry or wealth were put to death as friends of Geta upon the slightest unsupported charge of an unidentified accuser.

He killed Commodus’ sister [Cornificia], then an old woman, who as the daughter of Marcus had been treated with honour by all the emperors. Caracalla offered as his reason for murdering her the fact that she had wept with his mother over the death of Geta. His wife [Plautilla], the daughter of Plautianus, who was then in Sicily; his first cousin Severus; the son of Pertinax; the son of Lucilla, Commodus’ sister [Pompeianus]; in fact, anyone who belonged to the imperial family and any senator of distinguished ancestry, all were cut down to the last one.

Then, sending his assassins to the provinces, he put to death the governors and procurators friendly to Geta. Each night saw the murder of men in every walk of life. He burned Vestal Virgins alive because they were unchaste. Finally, the emperor did something that had never been done before; while he was watching a chariot race, the crowd insulted the charioteer he favoured. Believing this to be a personal attack, Caracalla ordered the Praetorian Guard to attack the crowd and lead off and kill those shouting insults at his driver.

The praetorians, given authority to use force and to rob, but no longer able to identify those who had shouted so recklessly (it was impossible to find them in so large a mob, since no one admitted his guilt), took out those they managed to catch and either killed them or, after taking whatever they had as ransom, spared their lives, but reluctantly.

(Herodian, History of the Roman Empire, 4.6)

Despite the bloodbath, Caracalla was not yet finished with his brother, and what he did next was, perhaps, indicative of the extreme hatred he had for Geta.

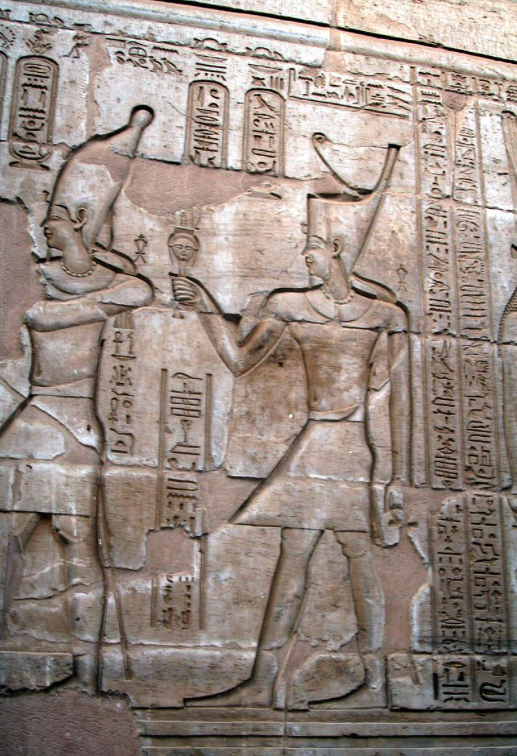

Caracalla now sought to fully erase his brother Geta’s very existence from the historical record in an act that has come to be called, in modern times, damnatio memoriae, the ‘condemnation of memory’.

All across the empire Geta’s name was ordered to be struck from documents and his image erased or destroyed in paintings, statuary, upon monuments, and coinage. Anywhere Geta appeared, he was to be erased.

Portrait of the Severan family with Geta’s face erased.

Due to the bloody start to his reign, Emperor Caracalla’s infamy was now solidified. His survival was due mainly to the loyalty of the troops, but as we shall see later in this blog series, even that would last for a finite amount of time. Caracalla was not his father, Septimius Severus, and he would prove that to the world he was so desperate to rule. It would only be a matter of time before his enemies caught up with him.

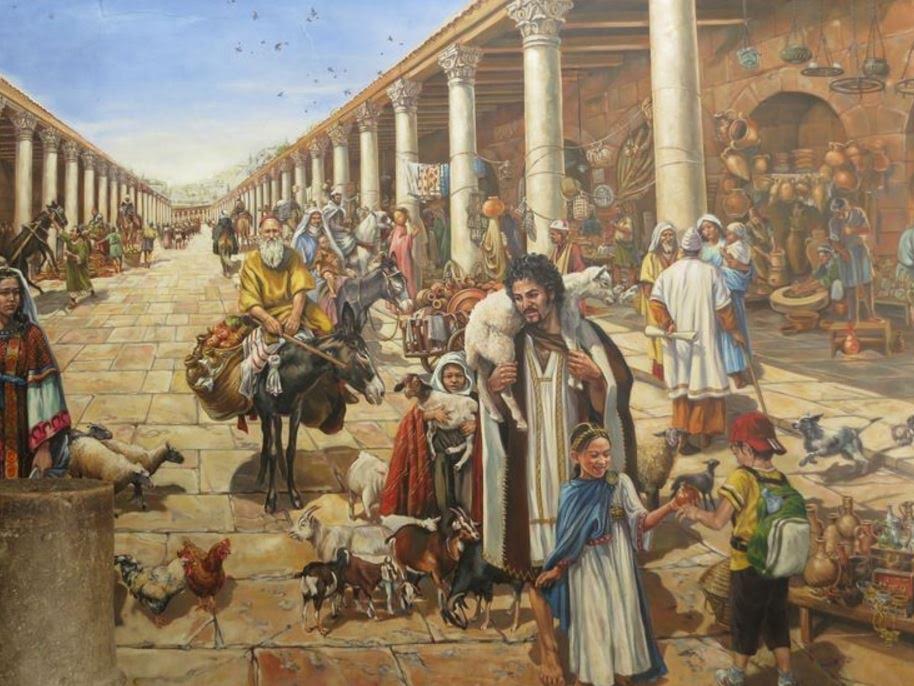

Part II – Travel and Transportation in the Roman Empire

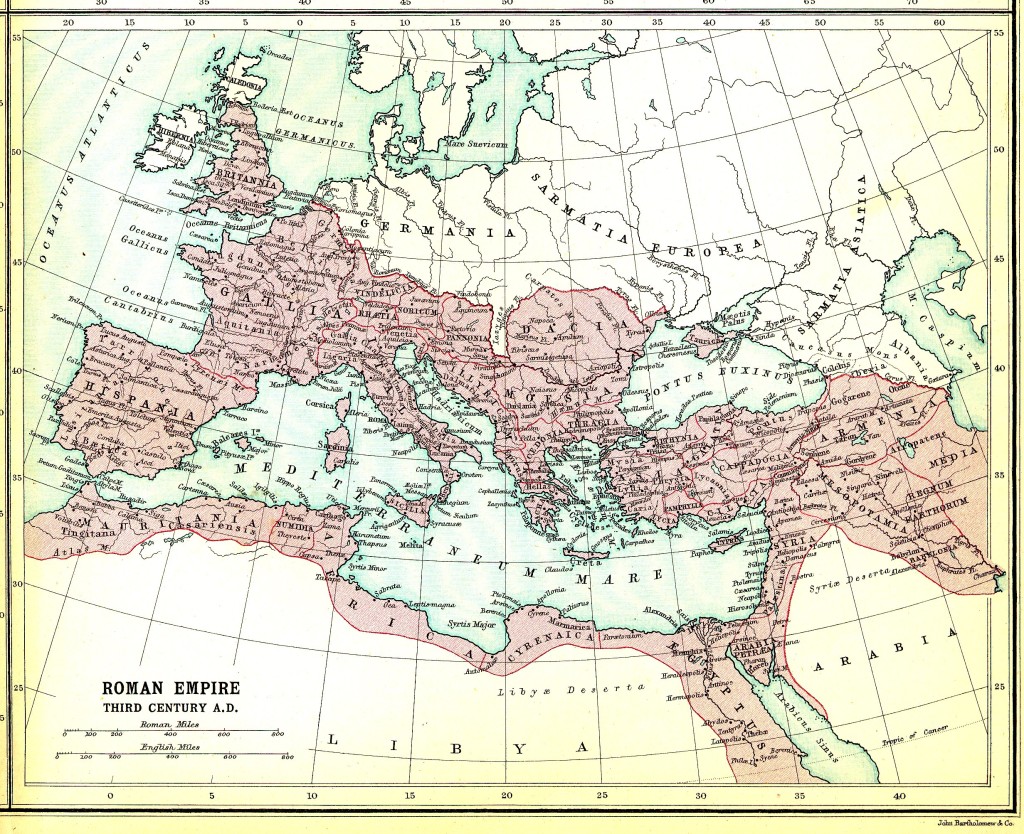

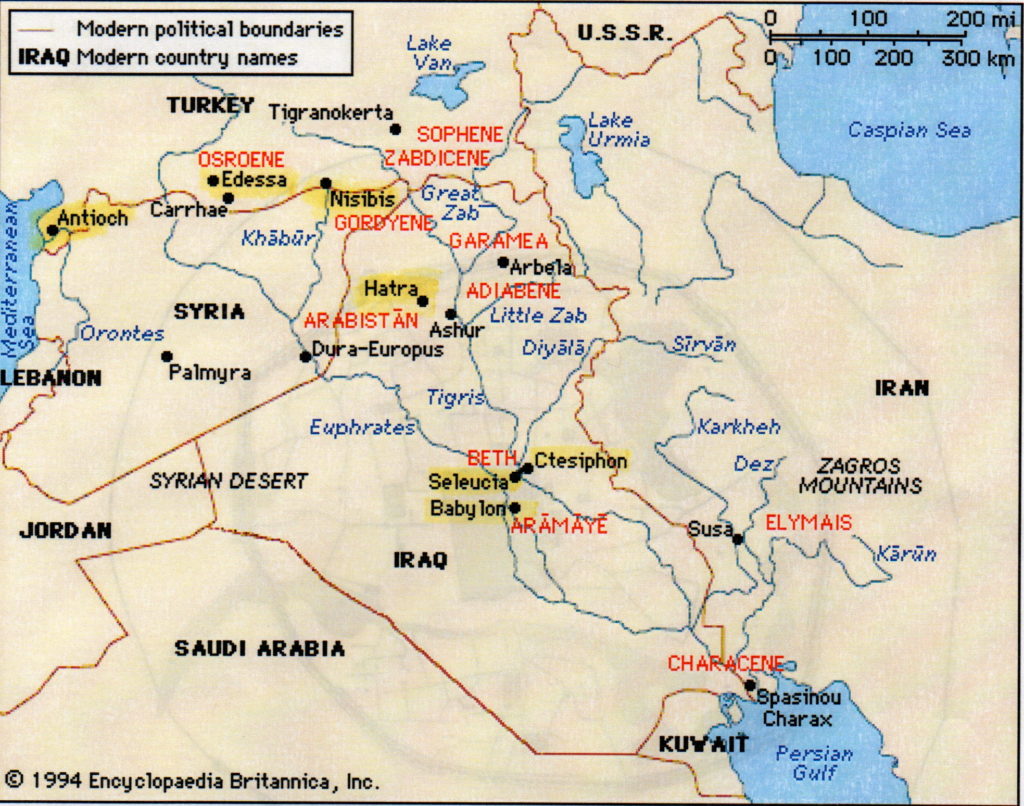

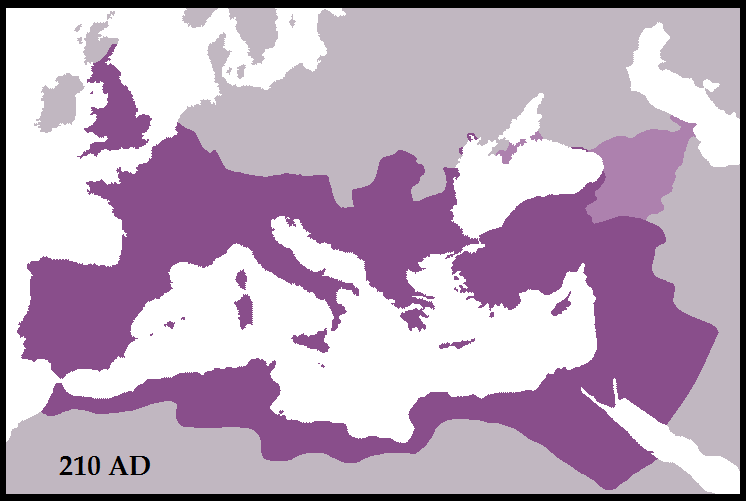

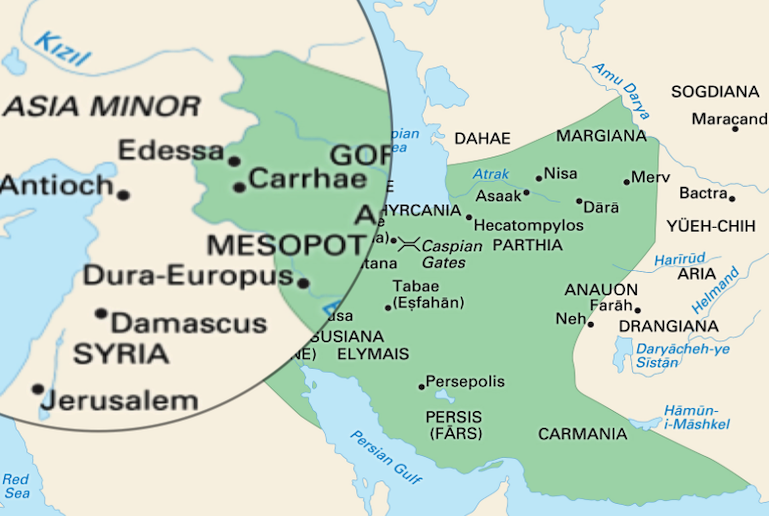

The Blood Road is an epic story that spans the Roman Empire from Britannia all the way to Parthia in the East. Travel is, naturally, a part of the story.

However, travel is something that we take for granted today. We decide we need to get somewhere, and we just go, be it nearby, or over a great distance across the ocean. We often take it for granted in fiction too; characters often need to get from point A to point B, and it happens.

But in the ancient world, travel wasn’t so easy. It required planning, and it took time.

There were also many factors involved such as destination, budget (not unlike today), mode of transportation, and time of year. Unless one was a soldier, or merchant, or someone wealthy, chances are that you might never have left your community.

So, when people did travel in the Roman Empire, how and why did they do so?

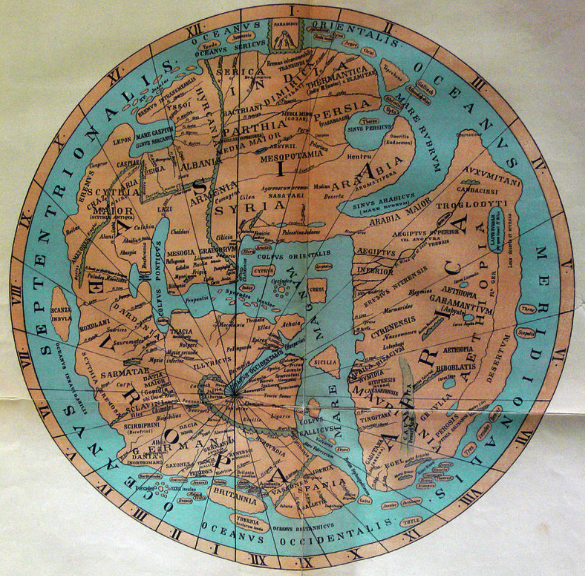

Ptolemy’s world map, reconstituted from Ptolemy’s Geography, circa AD 150, in the 15th century, indicating Sinae, China, at the extreme right. (Wikimedia Commons)

First off, we should probably discuss maps. We use maps today, and the Romans had maps. Geography was important, especially if you were planning a large scale invasion or military campaign, or even surveying for a new settlement. Not many maps from the Roman period survive, but copies of maps were made from originals. Sometime they were even rendered in paintings or mosaics.

Maps, geography and cartography are mentioned by some ancient authors such as Strabo, Polybius, Pliny the Elder, and Ptolemy. We also know that large wall maps of the world were commissioned by Julius Caesar, and then by Agrippa, during the reign of Augustus.

Much of our knowledge of place names and geography from the Roman world comes from what are called ittinerarium pictum, or ‘iteneraries’, which were travel itineraries accompanied by paintings. Perhaps the most well-known of these is Ptolemy’s Geography which included six books of place names with coordinates from around the Empire, including faraway places such as Ireland and Africa.

Another source is the Ravenna Cosmography. This was a compilation by an 11th century monk of documents dating to the 5th century A.D. It was made up of copies by a cleric at Ravenna, dating to around A.D. 700. This particular source gives lists of stations, river names and some topographical details.

Details of a map based on the 11th century Ravenna Cosmography (Wikimedia Commons)

The Notitia Dignitatum is a late Roman collection of administrative information which included lists of civilian and military office holders, military units and forts. The maps that accompanied this were medieval, but it is believed that they were derived from Roman originals of the fourth and fifth centuries A.D.

Perhaps the most important surviving example of an itinerary, however, is the Itinerarium Antoninianum, the ‘Antonine Itinerary’, which was a collection of journeys compiled over seventy-five years or more and assembled in the late 3rd century. It describes 225 routes and gives the distances between places that are mentioned. Some believe it was probably used for travel by emperors or troops. This particular source also included a maritime section with sea routes entitled Imperatoris Antonini Augusti itinerarium maritimum. The longest route in this itinerary appears to represent Caracalla’s trip from Rome to Egypt in about A.D 214-215, the exact time period for The Blood Road.

Map of Roman Britain based on the Antonine Itinerary, plotted by William Stukeley in the 1700s using the Itinerary as its source. (University of Kent)

Next, one cannot talk about travel in the Roman Empire without talking about one thing in particular: Roads.

There is a reason the expression ‘All roads lead to Rome’ exists. It was true, at least for a time. This is believed to have originally referred to the milliarium aureum, the ‘golden milestone’ near the temple of Saturn in the Forum Romanum, from which all distances were measured. It is believed that distances to specific cities or settlements were written upon it.

Roman roads, such as this section of the Fosse Way in Leicestershire, are still in use today. (photo: Geograph.org)

When it comes to roads, Rome was the best. In fact, Roman roads forever altered the empire and travel itself. Not only did Roman roads make troop movements much easier – with the troops building the roads themselves! – but they also opened up parts of the empire to trade and further settlement. They spread out from Rome like a titanic spider web connecting the eternal city to the farthest outposts.

There were also various types of road too, not just the broad, paved roads upon which vehicles and legions could travel. There were also small tracks, causeways, narrow streets, embanked roads or strata, lanes and more. Whether you were crossing the world, or crossing a settlement, roads of all types were useful.

The Roman empire in the time of Hadrian, showing the network of main Roman roads. (Wikimedia Commons)

Of course, with Roman roads, came Roman bridges over rivers that might have added days to a journey in order to reach a suitable crossing point. Travel was shortened in many ways by using Roman roads.

Now that we know how important roads were to the Roman Empire, how did people travel upon them?

When it came to the legions, marching was the order of the day for most troopers, and the average Roman soldier, fully laden, could travel up to 25 Roman miles in one day. For the average person living within the bounds of the Empire, walking was also the norm. This mode of travel was slower, to be sure, though roads made it much easier.

Apart from walking, there were of course other, faster modes of transportation such as by horse, pack animal, two-wheeled cart, and four-wheeled wagon. Obviously, these required one to have the funds to own or rent such animals and vehicles, but they did greatly cut back on the travel time.

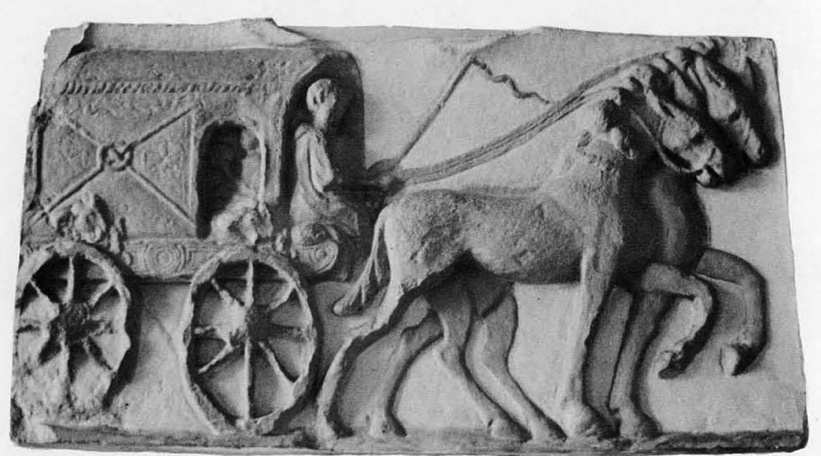

A Roman relief showing a four-wheeled, covered wagon (photo – Penn Museum)

The time of year and the weather were obvious factors when it came to travel upon roads, but also when it came to water routes open to travellers such as by river, open sea, and coastal sea travel.

When it comes to seafaring, the Romans had no such tradition until after the wars with Carthage which forced them to come to terms with the need for a navy. With the creation of that navy, Roman troops could be moved more quickly from Rome to Africa, for instance.

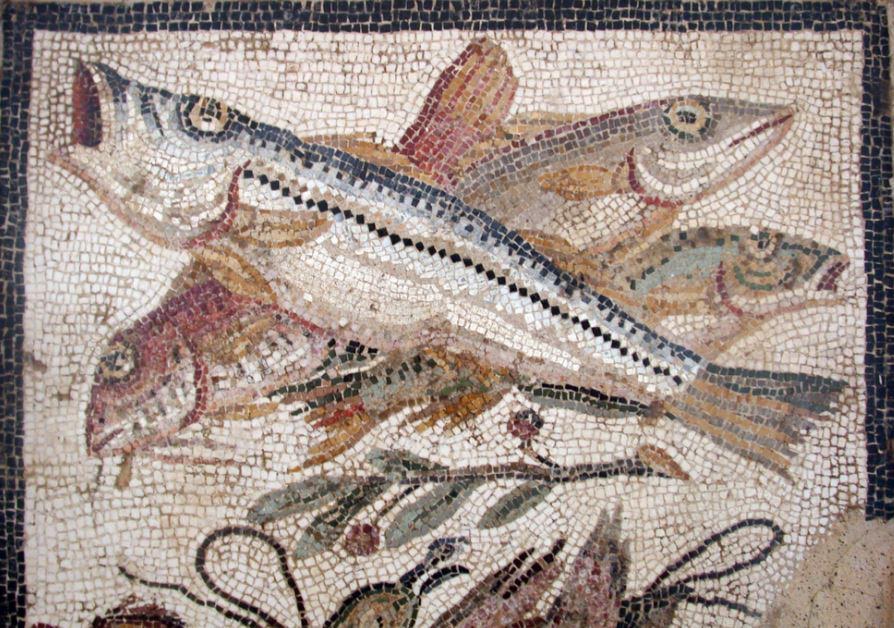

The other reason for travelling by sea or waterway was, perhaps more importantly, trade. The Roman Empire at its peak was vast and varied, and there was an enormous trade network that ensured raw materials such as lead and marble made it to construction sites as far away as Britannia, or from there to Rome itself. Perhaps the officers on Hadrian’s wall missed their favourite garum produced in Hispania, or wine from their family’s Etrurian estate?

A Roman cargo ship, or ‘corbita’ (image: naval-encyclopedia.com)

To transport large amounts of goods where they needed to be at the farthest reaches of the Empire, or to the heart of Rome itself, sea transport was the way to go, and massive ports such as those at Ostia, Carthage, Alexandria, and Piraeus were constantly alive with trade.

There were various types of ships, both commercial and military, but despite the efficiency of this mode of transport, it was even more restricted by the seasons and weather than travel over land. Sea travel could be absolutely treacherous, and the number of ancient shipwrecks that dot the coasts of the former Roman Empire are a testament to this.

The wreck of a 110-foot (35-meter) Roman ship, along with its cargo of 6,000 amphorae, discovered at a depth of around 60m (197 feet) off the coast of Kefalonia. (Photo: CNN)

If you want to read more about the various types of ships used in the Roman Empire, be sure to check out the Naval Encyclopedia page HERE.

As mentioned before, we often take travel for granted in the modern world, but it cannot be overstated how important travel was during the Roman Empire, nor how much Roman road and ship building opened up the world and the economy of Europe at the time. Yet another thing the Romans did for us!

The Port of Ostia, today and in the 2nd century A.D. (photo: BBC/The Portus Project)

I hope you’ve enjoyed this brief post about travel and transportation in the Roman Empire.

If you are interested in taking a look, one particular tool that was especially useful when researching and writing The Blood Road was Orbis: The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World. This special GIS tool uses ancient and modern source information to accurately create itineraries for travel between destinations in the Roman Empire, taking into account mode of transport, time of year, and whether travelling by land or sea. You can check that out HERE.

Part III – Communis Patria: The Constitutio Antoniniana

Next we’re going to take a brief look at one of the more unique acts of Emperor Caracalla: The Constitutio Antoninia.

As we shall see, this act had pros and cons, and it’s effects on the Roman world were far-reaching.

When we think about Emperor Caracalla, it’s hard to think of anything but blood and violence. After all, he may have begun his reign with a massacre in York, and then committed fratricide and ordered mass executions when he returned to Rome from Britannia.

The beginning of his reign was also punctuated by another act that has caused some debate among scholars over the years.

In A.D. 212, shortly after murdering his brother, Caracalla created an edict named the Constitutio Antoniniana which was, according to eminent historian, Michael Grant, “one of the outstanding features of the period, although whether it seemed the same to contemporaries is uncertain.”

So, what was the Constitutio Antoniniana? Why was it created? And what were the effects of this curious piece of legislation?

Let’s take each of these questions in turn.

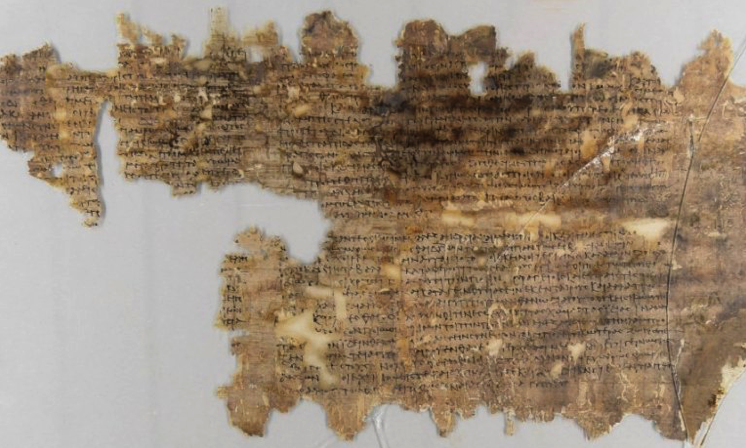

Giessen Papyrus 40 of the Constitutio Antoniniana

Basically, the Constitutio Antoniniana was an edict that granted citizenship to all freeborn men and women within the Roman Empire.

Think about that for a moment…

Whereas before, Roman citizenship had been primarily held by few, namely those who were from Italy itself, it was now held by every free man and woman across the whole of the Roman world. The only ones who appear to have been excluded were a group known as the dediticii, thought to be tribesman beyond the Danube and Euphrates frontiers who had recently been conquered by Rome.

This act had far-reaching impacts which we will look at shortly, but why was it created, and why at that particular moment in time?

There are a few possibilities.

Map of the Roman Empire at its greatest extent (Oxford Research Encyclopedias)

During the reign of Septimius Severus, Caracalla’s father, it is important to remember there there was a general shift happening, a more egalitarian movement in policy-making that sought to embrace all inhabitants of the Empire. Severus had previously, made drastic changes within the army itself by allowing legionaries to marry and by making it possible for men of equestrian status to move higher in the ranks into positions normally reserved for the senatorial class. This was the case for Lucius Metellus Anguis in the Eagles and Dragons series.

It is possible that Caracalla’s Constitutio Antoniniana was a next step in what was already his father’s policy-making direction. Let’s remember that Severus himself had been from Leptis Magna in Africa Proconsularis.

It is also important to remember that after the fall of the Praetorian prefect, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus, Septimius Severus appointed the legal jurists, Papinianus and Ulpianus as joint Praetorian prefects, clearly with a view to using their skills in drafting legislation. Of course, Papinianus perished during Caracalla’s proscriptions at the outset of his reign, but Ulpianus almost certainly had a hand in drafting the Constitutio Antoniniana.

It was a major step in the creation of the first, Roman Communis Patria, a commonwealth in which provincials and Italians were now on equal footing. This would have appealed to Caracalla as well, for he was obsessed with Alexander the Great who had sought to create a grand, pan-Hellenic world. Caracalla sought to emulate Alexander, and this may have been an extension of that obsession.

Apart from being in line with Severus’ policies, however, it is quite possible that one of the main reasons Caracalla issued this edict at that time was to distract the world from the murder of his brother, Geta.

As discussed in Part I of this series, fratricide was frowned upon, even though Rome’s founding was based on such an act (poor Remus!).

The She-Wolf suckling the brothers, Romulus and Remus

But we would be doing ourselves a disservice if we explained the creation of this important legislation by saying it was merely a distraction from murder. It had other uses.

As we know, after his brother’s murder, Caracalla needed to secure his position, and so he emptied the imperial coffers in order to bribe the Praetorian Guard and give more money to the legions. His father had always taught him that ensuring the loyalty of the military was of utmost importance, and this is exactly what Caracalla did. But it left him with few funds.

So, by granting citizenship to all freeborn men and women across the Empire, he instantly increased the tax revenues many times over. Citizens had to pay manumission and inheritance taxes to the state, and his tax collectors no doubt set about their work.

Roman Re-enactors on the March

Another important aspect of the Constitutio Antoniniana is that by greatly increasing the citizenry, many more men could enlist in Rome’s legions. To be a legionary, one had to be a Roman citizen, and previously, anyone not a citizen could only join the army as an auxiliary. It is possible that with his military goals in Germania, and perhaps for other campaigns to come, Caracalla was seeking to bolster Rome’s military, though his father had done that to a large extent already.

Lastly, we cannot ignore the possibility that the Constitutio Antoniniana may partly have been a play for popularity by Caracalla. With rumours of his brother’s murder circulating, he needed to win some popular appeal, and so this grand gesture of granting citizenship would have – he probably hoped – ingratiated him to those outside of Italy, while perhaps the increased tax revenues might have won him some support within the Italian peninsula.

Even people on the edge of the Empire were affected by the Constitutio Antoniniana.

Strangely enough, there is not much mention of the Constitutio Antoniniana, no great commemoration of the event. Why is that?

One reason may be that Caracalla was simply not liked. Certainly, contemporaries such as Cassius Dio, our main source for the period, did not like him and would never sing his praises.

Another possibility for the silence around the creation of the Constitutio Antoniniana could be that its effects upon the Empire left a lot to be desired.

What then were the effects of this important legislation on the Roman world?

Certainly for many, Roman citizenship would have been a boon, for it had always been a prized possession. For a provincial being granted equal status to an Italian, it would have seemed a good thing on the surface. Certainly, it had a levelling effect in the law courts where the law treated citizens differently to non-citizens.

Increased taxation, however, would have been a bitter pill to swallow for anyone, and this would not have been welcomed.

A relief thought to portray Roman tax collectors

When it comes to the military which Caracalla and his father so relied upon, the Constitution Antoniniana did increase the pool from which Caracalla could recruit legionaries, but there was a negative side to this as well.

It now became harder to attract ambitious people into the army, because now all soldiers were citizens. The non-citizen auxiliaries that made up the important cavalry alae, forces of archers, slingers and others, now ceased to exist. There were still native formations of numeri, but the army was permanently changed and now, being open to all, the desirability of being a Roman legionary was fast dwindling.

Lastly, by granting citizenship to all freeborn people across the whole of the Empire, Roman citizenship itself was now cheapened by the Severans’ equalizing tendencies. Citizenship had its privileges, including access to higher civilian and military offices. Now, however, this was greatly watered down, and the few who previously possessed citizenship would now have to compete with many more for prized positions.

This is perhaps one of the greatest impacts of the Constitutio Antoniniana. With the loss in status of citizenship over the following years after A.D. 212, a new elite began to evolve. It was no longer about citizens and non-citizens, or Romans vs. provincials. Rather, class distinction came to the forefront across the Empire with the formation of the honestiores and humiliores classes. Eventually, this class distinction became law, and where honestiores enjoyed legal privileges, the humiliores suffered more severe punishments. It is almost as if the entire Empire was regressing to the time when there was division among Patricians and Plebeians in Republican Rome.

When one reads this, it is hard not to wonder whether such class distinctions are a natural human state or tendency, but that’s a debate for another time.

Debate in the Senate over the Constitutio Antoniniana must have been furious. (Senate scene from the movie Fall of the Roman Empire, 1964)

I can’t help but admire – in an idealistic, and perhaps naive way – the equalizing goals of the Constitutio Antoniniana. After all, isn’t that something we are still striving for today? It is often at the heart of many modern political debates.

However, it is difficult for us – as it was, I suspect, for Caracalla’s contemporaries – to get past the man that Emperor Caracalla was, and the actions he had taken at the outset of his reign. He had proved himself to be cruel and spiteful. He was not a good emperor. And so, it is possible that anything ‘good’ that he might have attempted was probably lost behind a scrim of blood.

Despite its strong democratic note, the Constitutio Antoniniana is also believed, by some, to be one of the causes for the degeneration of the Roman Empire.

What do you think? Let us know in the comments below.

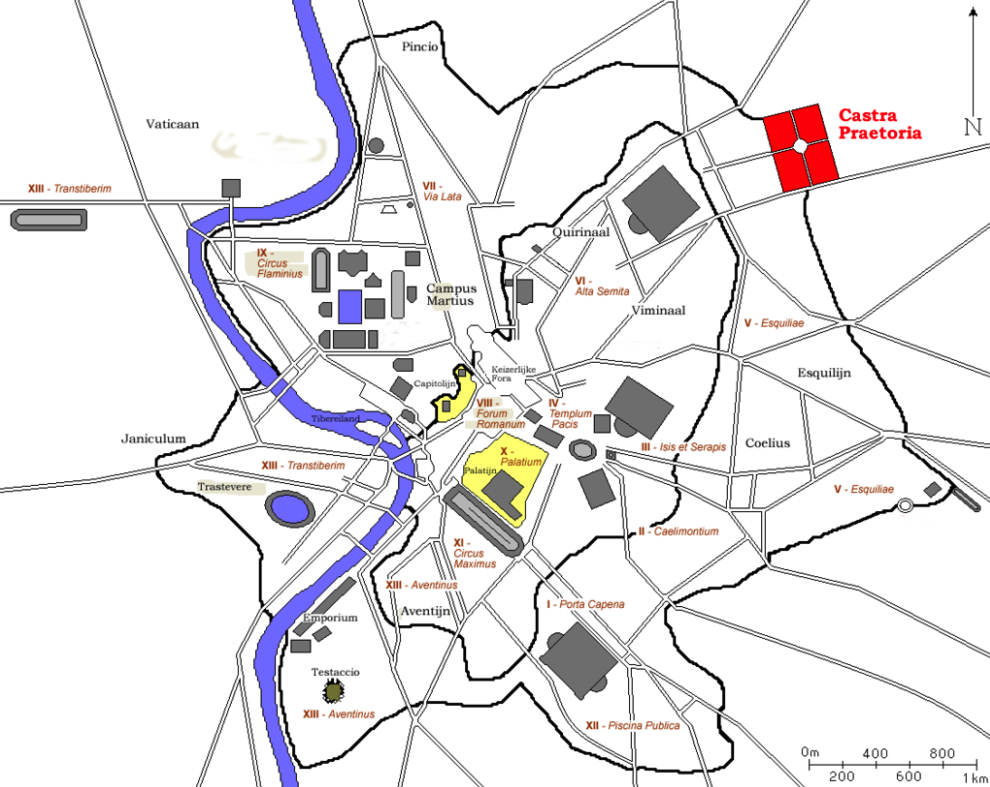

Part IV – Position of Power: The Praetorian Guard and the Castra Praetoria of Rome

Praetorian Guard officers

Throughout the Eagles and Dragons series, members of the Praetorian Guard and their prefects play a key role in what is happening in the empire, and are often involved in the court intrigues that accompany the imperial entourage. However, this is not just the case in fiction.

The Praetorian prefects and their troops were often at the heart of imperial affairs, wielding tremendous power and influence. They had the ability to make or break emperors.

When we hear the word ‘Praetorian’, it’s difficult not to think on some of the most infamous prefects in history such as Lucius Aelius Sejanus who conspired against Emperor Tiberius, or Quintus Naevius Sutorius Macro, who may have ordered the death of Tiberius and then put Caligula on the throne. Or how about Pescennius Niger, who made his play for the throne against Septimius Severus and lost after being prefect for a year under Commodus? There were also some prefects who went on to even greater heights such as Titus Flavius Vespasianus, the future Emperor Titus, who served as prefect under his father Vespasian.

In the Eagles and Dragons series which takes place during the reigns of Septimius Severus and Caracalla, we see how powerful and dangerous Gaius Fulvius Plautianus and Marcus Opellius Macrinus were, and how influential the jurists Papinianus and Ulpianus were.

There is a long list of Praetorian prefects throughout the history of the Roman Empire, some excellent and loyal, others power hungry and willing to do whatever it took to consolidate the great power and wealth to which they had access.

But who exactly were the Praetorian Guard and how were they organized? We’ll take a brief look at their history next.

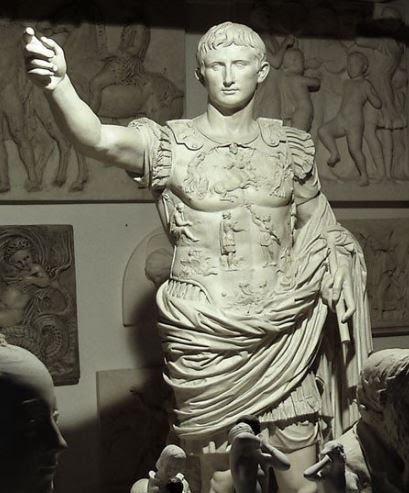

Emperor Augusts

The name of the Praetorian Guard comes from the small group of men who, during the Republic, would accompany magistrates, or praetors, on campaign.

After the murder of Julius Caesar in March of 44 B.C., Marcus Antonius created a personal Praetorian guard detail for himself made up of six thousand legionaries.

But it was Emperor Augustus who really formalized the Praetorian Guard around 27 B.C. when he adapted this idea to create an Imperial Guard. The Praetorians were mainly charged with ensuring the ruler’s security, but there were other duties as well.

The Praetorians and their prefects were also responsible for sentry duty at the palace, and escorting the emperor and his family members. They acted as a sort of riot police in Rome, standing guard over events such as at the Circus Maximus, the Colosseum and the theatre. They operated the city prison and carried out executions in Rome, especially of high status prisoners. The Praetorians were also a sort of political and secret police.

One might think that the Praetorians had it easy compared with legionaries who were constantly fighting on the front lines of the Empire, and you would be right. But they could also fight, and sometimes they did when the emperor went on campaign. They excelled at this too.

The Praetorian Guard were the elite of Rome’s military might.

The Praetorian Guard (Illustration by Peter Dennis)

When the Praetorians were first formed, the men had to be Italian, from Latium, Etruria, and Umbria, and later also from Cisalpine Gaul and other territories. Men were recruited between 15 and 32 years of age.

In Rome especially, the Praetorians were seen as a military force that was used to enforce the will of the emperor upon others. They discouraged plotting and rebellion, that is, unless they were doing it themselves. And because they could create or destroy emperors and were, at times, the true power in Rome, the post of Praetorian Prefect naturally attracted power-hungry men such as some of those named above.

There are several instances where the Praetorians went too far, one being the auctioning of the imperial throne after the death of Commodus.

When Septimius Severus emerged the victor after the subsequent civil war, he made sure to replace the entire Praetorian Guard with men from his own legions, men whose loyalty could be relied upon. His one mistake was, as other emperors had also done, trusting the wrong person in the position of Praetorian Prefect.

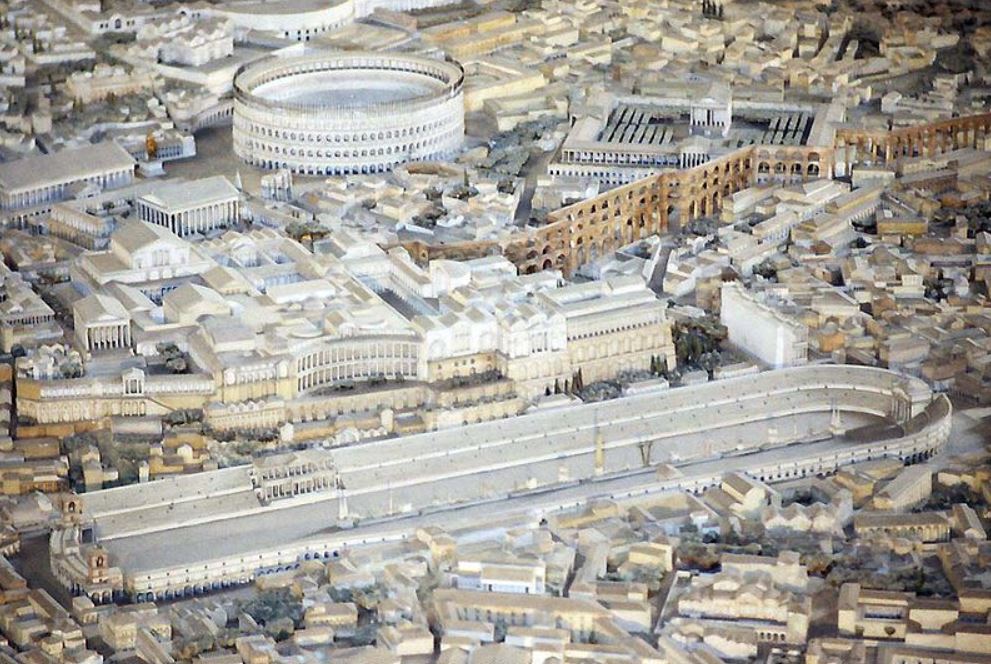

Model of ancient Rome with the Circus Maximus in the foreground

In spite of the air of corruption, or perhaps because of it, many men aspired to be a part of the Praetorian ranks. Apart from the power, there are other reasons why the Guard attracted men. It was just a better gig!

First of all, Praetorians had a shorter term of service before they could retire. They served for 16 years, whereas legionaries had to serve for a minimum of 20. They received much better pay as well. For example, in about A.D. 14, a Praetorian guardsman would have received 720 denarii per annum, compared with a legionary’s 225 denarii. Upon retirement, Praetorians received a bonus of 20,000 sestercii, and legionaries received 12,000 sestercii.

One reason that has been suggested for the difference in pay is that Praetorians probably had fewer opportunities to loot since they were not on campaign as much as regular legionaries. Whether or not this is true, it seems like being a Praetorian was just a more desirable deal, and many legionaries were jealous of their lot.

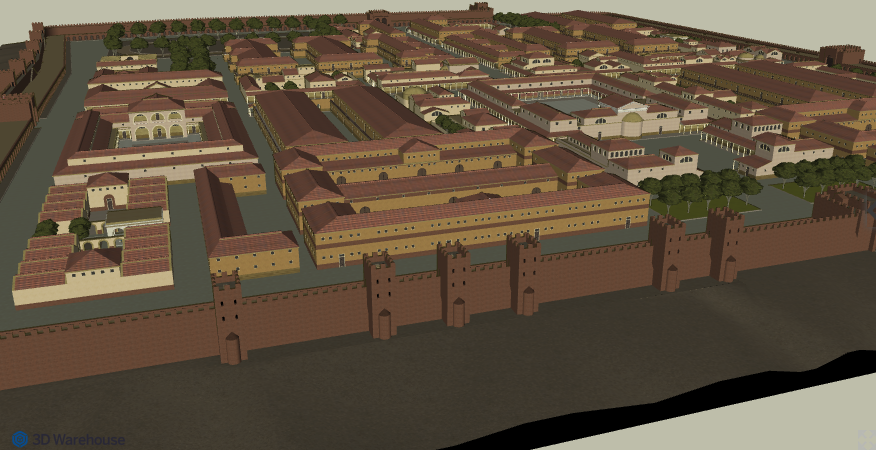

The Castra Praetoria and ancient Rome (Wikimedia Commons)

Despite their differences, however, the Praetorian Guard had a similar makeup to the legions.

There were nine cohorts, each led by a tribune and six centurions. The tribunes reported to the Praetorian Prefect. There was also a princeps castrorum, or ‘camp prefect’, and a head centurion, or trecenarius, who was equal in status to the tribunes, and who commanded 300 speculatores, who served as cavalry scouts or Praetorian spies.

There has been some disagreement among scholars about the number of troops in the Praetorian cohorts. Some believe it was 500, and others 1000. But during the reign of Severus, the number of troops in a Praetorian cohort was 1000 men.

Originally, there were two Praetorian prefects at a time who supervised the Guard, but during the reign of Tiberius, the emperor appointed just one, Sejanus, and he became very powerful indeed. Severus made the same mistake with Plautianus.

It was around A.D. 20-23 that Emperor Tiberius and Sejanus really solidified the power of the Praetorians, and gave the Guard a power base from which it could operate: the Castra Praetoria.

Until the reign of Severus, who stationed his II Parthica legion at Albanum, the Praetorian Guard was the only military unit permitted by law to be stationed in Italy itself.

The Castra Praetoria at Rome was their fortress.

This 17 hectare (40 acre) fortress, with a training ground beside it, was built around A.D. 23 by Tiberius and Sejanus. It was originally located outside of the Servian walls of Rome on the Viminal hill, which included the Esquiline plateau. Much of the walls still stand today, and house a modern garrison of the Italian army.

The Castra Praetoria was smaller than a full legionary castrum, but it is believed that with the presence of barracks around the walls, and of two-storey barrack blocks within, the capacity may have been as much as 12,000 troops!

That is quite a force of men within Rome!

The walls were of concrete and brick and at first measured 3.5 meters high. They were heightened by the Praetorian prefect, Macrinus, during the reign of Caracalla (A.D. 211-217). In A.D. 271, Emperor Aurelian built new walls around the city of Rome and at that time incorporated the Castra Praetoria into them, again raising the height of the fortress walls, and also adding towers and battlements.

In A.D. 310, Maxentius raised the walls even more to prepare for the coming confrontation with Constantine.

The Castra Praetoria today (Wikimedia Commons)

Because the Praetorians had been at the heart of so many conspiracies and plays for power over the years, emperors such as Severus sought to punish them severely or replace the Guard altogether.

After Constantine the Great defeated Maxentius at the battle of the Milvian Bridge in A.D. 312, Constantine went one step further to finally put an end to the machinations of this powerful and often corrupt military force. He demolished the inner wall of the Castra Praetoria, and dissolved the Praetorian Guard for good. From that time on, the role of Praetorian prefect became a purely administrative role.

Arch of Constantine, Rome

The history of the Praetorian Guard is fascinating, as is the behaviour of the Praetorian prefects who held the post over the roughly 300 year history of the Guard.

In the Eagles and Dragons series, which takes place during the reigns of Severus and Caracalla, the power and influence of the Praetorians and their prefects is at the centre of the political intrigues behind-the-scenes.

This post has but scratched the surface, but I hope that you have learned a bit more about this force of Rome’s elite soldiers at the heart of the Empire.

Part V – Carthago Nova: From Punic Outpost to Center of Roman Trade

Roman Spain, with Carthago Nova at the bottom right, on the Mediterranean coast

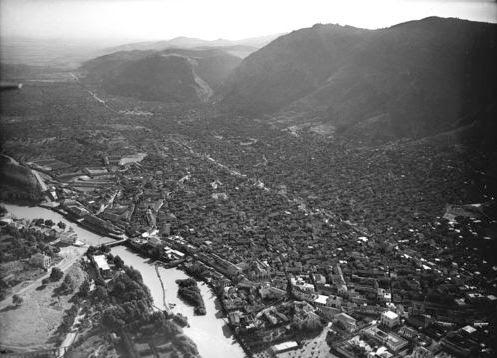

In Part V of this blog series we’re going to be taking a look at one of the locations visited by the main characters: the Iberian city of Carthago Nova, or, ‘New Carthage’.

One of the joys of writing historical fiction in the Roman Empire is that you have myriad options for setting open to you. The Roman world was vast and varied. It never gets boring. Like the people inhabiting it, the terrain and settlements are all different. The Roman Empire is perhaps the most diverse, multi-cultural civilization in ancient human history.

Carthago Nova, modern Cartagena in southern Spain, is no exception, and its history and development are fascinating. In this post, we’re going to take a very brief look at this ancient settlement.

Remains of Punic walls of Qart Hadasht

It [Carthago Nova] stands about half-way down the coast of Iberia in a gulf which faces south-west, running about twenty stades inland, and about ten stades broad at its entrance. The whole gulf is made a harbour by the fact that an island lies at its mouth and thus makes the entrance channels on each side of it exceedingly narrow. It breaks the force of the waves also, and the whole gulf has thus smooth water, except when south-west winds setting down the two channels raise a surf: with all other winds it is perfectly calm, from being so nearly landlocked. In the recess of the gulf a mountain juts out in the form of a chersonese, and it is on this mountain that the city stands, surrounded by the sea on the east and south, and on the west by a lagoon extending so far northward that the remaining space to the sea on the other side, to connect it with the continent, is not more than two stades. The city itself has a deep depression in its centre, presenting on its south side a level approach from the sea; while the rest of it is hemmed in by hills, two of them mountainous and rough, three others much lower, but rocky and difficult of ascent; the largest of which lies on the east of the town running out into the sea, on which stands a temple of Asclepius. Exactly opposite this lies the western mountain in a closely-corresponding position, on which a palace had been erected at great cost, which it is said was built by Hasdrubal when he was aiming at establishing royal power. The remaining three lesser elevations bound it on the north, of which the westernmost is called the hill of Hephaestus, the next to it that of Aletes,—who is believed to have attained divine honours from having been the discoverer of the silver mines,—and the third is called the hill of Cronus. The lagoon has been connected with the adjoining sea artificially for the sake of the maritime folk; and over the channel thus cut between it and the sea a bridge has been built, for beasts of burden and carts to bring in provisions from the country.

(Polybius, Histories, 10.10)

Coin showing image of Hasdrubal the Fair

Originally, Carthago Nova, which is its later Roman name, may have been a Phoenician trading centre named ‘Mastia’. However, the settlement really took off and began to flourish under Carthage as Qart Hadasht (meaning ‘New City’) which was founded by the Carthaginian general Hasdrubal the Fair, the son-in-law of Hamilcar Barca, in 228 B.C.

After Carthage took the Iberian peninsula, Qart Hadasht became the seat of Punic power there. It thrived as a trade centre, but also as a supply station and base of operations from which, during the Second Punic War, Hannibal would strike out for northern Italy.

Qart Hadasht thrived because of trade, the excellent port, and the nearby silver mines. But success was a double-edged gladius. All the success the city enjoyed angered other trading centres, especially Massilia, an allied Roman city.

And Massilia complained to Rome.

Bust of Scipio Africanus

By the time the second Punic war came about, Rome was taking a closer look at the problem of Qart Hadasht. Actually, it was one Roman in particular: Publius Cornelius Scipio.

He [Scipio] therefore rejected that idea altogether: but being informed that New Carthage was the most important source of supplies to the enemy and of damage to the Romans in the present war, he had taken the trouble to make minute inquiries about it during the winter from those who were well informed. He learnt that it was nearly the only town in Iberia which possessed a harbour suitable for a fleet and naval force; that it lay very conveniently for the Carthaginians to make the sea passage from Libya; that they in fact had the bulk of their money and war material in it, as well as their hostages from the whole of Iberia; that, most important of all, the number of fighting men garrisoning the citadel only amounted to a thousand,—because no one would ever suppose that, while the Carthaginians commanded nearly the whole of Iberia, any one would conceive the idea of assaulting this town; that the other inhabitants were exceedingly numerous, but all consisted of craftsmen, mechanics, and fisher-folk, as far as possible removed from any knowledge of warfare. All this he regarded as being fatal to the town, in case of the sudden appearance of an enemy. Nor did he moreover fail to acquaint himself with the topography of New Carthage, or the nature of its defences, or the lie of the lagoon: but by means of certain fishermen who had worked there he had ascertained that the lagoon was quite shallow and fordable at most points; and that, generally speaking, the water ebbed every day towards evening sufficiently to secure this. These considerations convinced him that, if he could accomplish his purpose, he would not only damage his opponents, but gain a considerable advantage for himself; and that, if on the other hand he failed in effecting it, he would yet be able to secure the safety of his men owing to his command of the sea, provided he had once made his camp secure,—and this was easy, because of the wide dispersion of the enemy’s forces. He had therefore, during his residence in winter quarters, devoted himself to preparing for this operation to the exclusion of every other: and in spite of the magnitude of the idea which he had conceived, and in spite of his youth…

(Polybius, Histories, 10.8)

As we know, Scipio (later known as ‘Africanus’ after his victory over Hannibal), was a smart general. He did his research before attacking Qart Hadasht while Hannibal was attacking Italy.

As a result, the Iberian city was taken by Scipio in 209 B.C. and became known as ‘Cathago Nova’, which literally means ‘New New City’.

Digital reconstruction of Roman Carthago Nova

Carthago Nova, or ‘Colonia Urbs Julia Nova Carthago’, played an important role in Rome’s economy over the years. It was one of Rome’s major centres of trade and one of the main suppliers of the silver which was so important to pay Rome’s legions.

From Carthago Nova, Iberian goods were shipped to Italy and all over the Empire, including silver, salt, fish for garum, grain, and esparto grass which was used for rope making and basket weaving.

Under Roman rule, it was a safe city, and was the third major city in Iberia after Tarraco and Corduba.

In 44 B.C. it was made a colonia by Julius Caesar in recompense for the city’s help in his civil war against Pompey and, as a result, all free-born men of Carthago Nova were made Roman citizens.

Augustus showed further favour to the city by giving it new streets, a theatre, a proper forum, various monuments, an ‘Augusteum’, temples and a college.

Remains of the Roman theatre of Carthago Nova (today’s Cartagena)

By the mid-third century, after the period in which The Blood Road takes place, Carthago Nova fell on hard times with the disruption of the silver mining operations, and the abandonment of the eastern part of the city.

Emperor Diocletian tried to help the city by making it the capital of his newly-created province of Hispania Cathaginensis in around A.D. 298, but the respite only lasted for a short time.

In A.D. 409, the Vandals took the city, and it subsequently fell into the hands of the Visigoths in A.D. 425. From then on, it seemed Carthago Nova was destined to be ruled through a revolving door with power passing to the Byzantines, the Moors, and then into Christian hands during the Spanish Reconquista of the late Middle Ages.

This is the fascinating thing about ancient cities; no matter which one you choose to look at, you will find a long, rich history, marked by ups and downs. The fortunes of these cities ebbed and flowed like the sea itself, but more often than not, when you research them, you will find that Rome was there.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this brief post on the history of Carthago Nova.

Part VI – Pastoral Idyll: A Brief Look at Roman Etruria

Today, when one thinks of Tuscany, one inevitably has a picture of an idyllic pastoral setting dotted with vineyards overlooked by fortified medieval farmhouses, and medieval cities adorned with some of the greatest examples of western art that we can imagine. The Renaissance is often the age we conjure when we think of Tuscany. I know I do!

I love Tuscany. I’ve visited there for pleasure and research, and it is always on my list of places to return to. You can read one of my posts about visiting Tuscany by CLICKING HERE.

There is no doubt at all that Tuscany is extremely rich in history, but that history is not exclusively Medieval. On the contrary, the history of Tuscany goes much farther back than the Middle Ages and the era of the Medici.

Etruscan funerary monument with man and woman dining together

Of course, the name of Tuscany comes from the Etruscans, those people who inhabited that beautiful land and from which the kings of Rome originated. Etruscan culture and religion was extremely rich, and it is the Etruscans who were largely responsible for the import of Greek culture and religion to Italy, including wine making and olive growing.

But we’re not here to talk about the Etruscans today. If you would like to read about the Etruscans, I urge you to read my previous post on The Elusive Etruscans HERE.

Today we’re going to be taking a brief look at Etruria during the Roman period. What was Roman Etruria like? What role did it play in the broader Italian peninsula and the Empire itself?

Ancient Etruria (Wikimedia Commons)

During the period of Etruscan hegemony, the cities of Tuscany with which we are familiar today were not necessarily the primary settlements. The settlements of Veia (Veii), Velsna (Volsinii), Tarchina (Tarquinii), Perusana (Perusia), Aritium (Aretium), Clusium (Cortona) and a few others were more active.

The settlements that tourists are attracted to today, such as Florentia (Florence), Luca (Lucca), Pisae, and Saena Iulia (Siena) thrived more under the Romans, and then reached their peaks during the Middle Ages. To read about the origins of Roman Florence, CLICK HERE.

If you can ignore some of the ‘modern’ architecture and passing cars of today’s Tuscany, however, you can catch a glimpse of what ancient Etruria was like. It was, of course, a place rich in art and religion under the Etruscans, but after the fall of the kings especially, Rome began to put its mark on Etruria.

Vineyards in Tuscany

Roman roads such as the via Aurelia, the via Clodia, the via Cassia, and the via Flaminia were extended through the land, aqueducts and sewers were built, and there were more public and private construction projects.

Etruscan culture was not, however, erased by Rome. It was assimilated and adopted, especially when it came to religious arts such as augury and haruspicy. Haruspicy, the art of divining the will of the Gods through the examination of entrails after sacrifices (ex. the liver), and the reading of omens, prodigies and portents was a uniquely Etruscan skill that was adopted by Rome. Both the Senate and the army used haruspices who were trained in Etruria.

Etruscan bronze liver that may have served as an instructional model for a haruspex (Wikimedia Commons)

When it came to Roman Etruria though, agriculture was the order of the day, not only as a means of food production, but also as a civilized pastime for the Roman elite.

Roman Etruria was by and large a villa economy of latifundia, agricultural estates, of which the villas were the centre.

But the Romans considered farming not only as a means for income and food production, but also as a civilized retreat from the stresses of life too. Writers such as Cato the Elder, Varro and Columella write extensively about the agricultural life.

There was a certain moral superiority in farming, with a stress on learning and proper estate management.

One who devotes himself to agriculture should understand that he must call to his assistance these most fundamental resources: knowledge of the subject, means for defraying the expenses, and the will to do the work. For in the end, as Tremelius remarks, he will have the best-tilled lands who has the knowledge, the wherewithal, and the will to cultivate them. For the knowledge and willingness will not suffice anyone without the means which the tasks require; on the other hand, the will to do or the ability to make the outlay will be of no use without knowledge of the art, since the main thing in every enterprise is to know what has to be done — and especially so in agriculture, where willingness and means, without knowledge, frequently bring great loss to owners when work which has been done in ignorance brings to naught the expense incurred. Accordingly, an attentive head of a household, whose heart is set on pursuing a sure method of increasing his fortune from the tillage of his land, will take especial pains to consult on every point the most experienced farmers of his own time; he should study zealously the manuals of the ancients, gauging the opinions and teachings of each of them, to see whether the records handed down by his forefathers are suited in their entirety to the husbandry of his day or are out of keeping in some respects.

(Columella, De Re Rustica, 1.1)

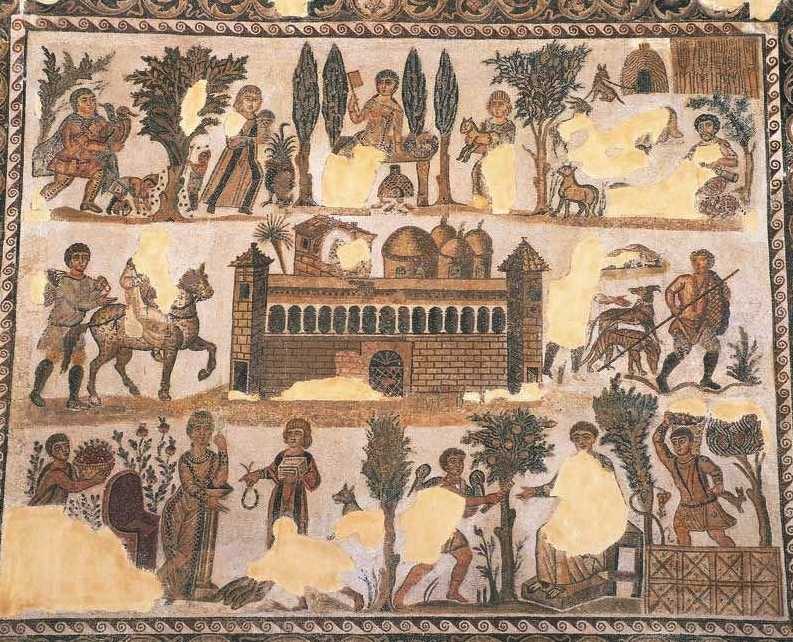

Mosaic depicting Roman country life and activities.

When we think of Tuscany today, one of the first things that comes to mind is wine. Chianti is certainly my favourite nectar! The wine trade in Etruria was begun by the Etruscans through their contact with the Greeks in about the 6th century B.C., but during the Roman period, Etrurian wine was imported throughout the Empire.

This wine trade was eventually overtaken by production in Hispania and Gaul in the 1st century B.C. but wine production did continue as an important part of the villa economy in Etruria.

The other main crops in Roman Etruria were olives and olive oil production, which continues to this day in the region, alongside wine-making.

The villa rustica was at the heart of this world, and even as you drive around today, you will see villas and farmhouses at the centre of grape and olive crops amongst those unmistakable Tuscan hills.

Tuscan farm

Other activities on latifundia were the rearing of various poultry, bees, boar, fruit trees which required a knowledge of grafting, fresh water fish ponds, hare warrens, and even such things as that most Roman of delicacies, dormice.

Farming was socially acceptable to elite Romans, but it was also frowned upon to have a lavish villa that did not produce. It was considered poor form to neglect agriculture. Cato the Elder certainly had his opinions about what constituted a good estate:

When you are thinking of acquiring a farm, keep in mind these points: that you be not over-eager in buying nor spare your pains in examining, and that you consider it not sufficient to go over it once. However often you go, a good piece of land will please you more at each visit. Notice how the neighbours keep up their places; if the district is good, they should be well kept. Go in and keep your eyes open, so that you may be able to find your way out. It should have a good climate, not subject to storms; the soil should be good, and naturally strong. If possible, it should lie at the foot of a mountain and face south; the situation should be healthful, there should be a good supply of labourers, it should be well watered, and near it there should be a flourishing town, or the sea, or a navigable stream, or a good and much travelled road. It should lie among those farms which do not often change owners; where those who have sold farms are sorry to have done so. It should be well furnished with buildings. Do not be hasty in despising the methods of management adopted by others. It will be better to purchase from an owner who is a good farmer and a good builder. When you reach the steading, observe whether there are numerous oil presses and wine vats; if there are not, you may infer that the amount of the yield is in proportion. The farm should be one of no great equipment, but should be well situated. See that it be equipped as economically as possible, and that the land be not extravagant. Remember that a farm is like a man — however great the income, if there is extravagance but little is left. If you ask me what is the best kind of farm, I should say: a hundred iugera of land, comprising all sorts of soils, and in a good situation; a vineyard comes first if it produces bountifully wine of a good quality; second, a watered garden; third, an osier-bed; fourth, an oliveyard; fifth, a meadow; sixth, grain land; seventh, a wood lot; eighth, an arbustum; ninth, a mast grove.

(Cato the Elder, De Agricultura, Book I)

The Villa Poppaea is an ancient luxurious Roman seaside villa (villa maritima) near Naples. (Wikimedia Commons)

Villa rusticae with successful and efficient farming production were considered appropriate and the most profitable in Roman Etruria, but we must also remember that Etruria had a long coastline.

Apart from the villa rustica, the villa maritima also played a role in the Etrurian economy. The primary focus of these estates was fish breeding, though this was not as prestigious a past-time as farming to some Romans.

Though Roman Etruria did have larger settlements such as Florentia, Veii, Volterrae and Clusium, the overall picture we have of Roman Etruria is one of agriculture, much as it is to this day. As the empire expanded, Etrurian production of things such as wine and oil would have been overtaken by other provinces, but it would still would have been a place where elite Romans escaped the trials of life, but also enabled them to make an income from their lands, that is, if they ran them well.

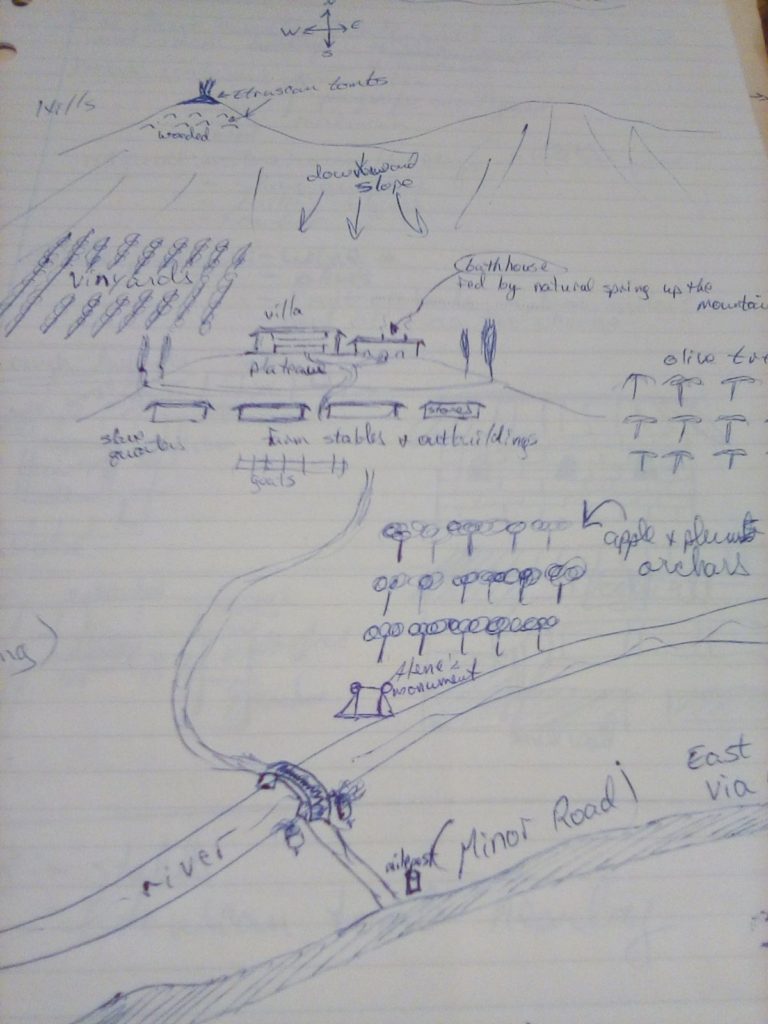

If you are familiar with the Eagles and Dragons series, you will recognize the Metellus family villa in Etruria as a villa rustica, handed down from one generation to the next. It makes an appearance in The Blood Road.

Early sketch of the Metellus villa in the Eagles and Dragons series. An example of a ‘villa rustica’.

The fictional Metellus villa came about as an amalgam of various sites I’ve visited in Tuscany over the years, and each time I’ve returned to it in fiction, I feel a familiar sense of awe at the beauty of that ancient landscape. It is quite unlike anywhere else in the world.

In a way, despite the changes in architecture and technology, Tuscany today is not too dissimilar to the Etruria of yesterday. You just need to know where to look.

Part VII – Delphi: Visiting the Sanctuary of a God

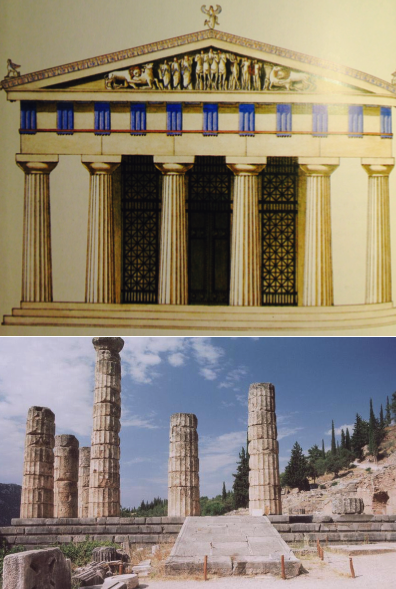

Speculative illustration of ancient Delphi by French architect Albert Tournaire.

Just as Delphi is perhaps one of the most well-known historical sites of Greece today, it was also one of the most famous and important places in the ancient world, sacred to both Greeks and Romans.

In this post, however, we’re not going to be discussing the history of Delphi. If you would like to read about that and my own experience walking through the sanctuary, you should definitely read this previous post by CLICKING HERE.

In this seventh part of The World of The Blood Road, we’re going to walk alongside ancient pilgrims, or theopropoi, on their way to consult the Pythia, the famous oracle of Apollo at Delphi.

…the high road to Delphi becomes both steeper and more difficult for the walker. Many and different are the stories told about Delphi, and even more so about the oracle of Apollo. For they say that in the earliest times the oracular seat belonged to Earth….

…I have heard too that shepherds feeding their flocks came upon the oracle, were inspired by the vapour, and prophesied as the mouthpiece of Apollo.

(Pausanias, Description of Greece, 10.5.5)

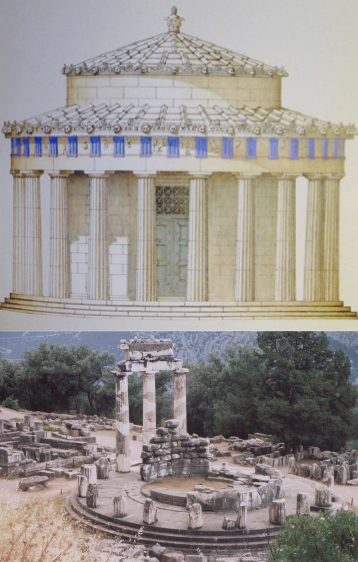

The peaceful sanctuary of Athena Pronaia

People would come from all over the Greek and Roman world to consult the oracle at Delphi who spoke the words of Apollo himself, the god of art, music, healing and prophecy, common to both Greeks and Romans. More often than not, they would come from very far away to do this, but when they arrived at Delphi, they could not just step into line and wait to see the oracle in the temple. There was a process.

First of all, you had to get there, and whether you came over land from the direction of Thebes, or from the ancient port of Kirrha on the gulf of Corinth, you had to climb your way up to the god’s eyrie.

Timing was important, for the oracle was not there all day, everyday. The priests of the temple could give simple answers to simple questions by individuals regularly, but for cities seeking wisdom, or individuals with weighty questions, the Pythia herself would give her oracles once every month on the seventh day, except for the three months of winter when Apollo was said to be in the land of the Hyperboreans. During Winter, Dionysos was said to watch over Delphi.

Whenever you arrived in Delphi, you would probably have stopped at the sanctuary of Athena Pronaia to thank the gods for bringing you there safely.

The Tholos in the sanctuary of Athena Pronaia (reconstruction by K. Iliakis)

This sanctuary was the sort of gateway or ‘entrance’ to the sanctuary of Apollo. It was located down the mountain from the main sanctuary, along the road from Thebes. Here, there were temples to Athena, Hygeia, Zeus and others. There were altars and a hero shrine too, all within the walled enclosure. If you were Roman, you might have recognized the statue of Hadrian looking over the sanctuary, for he loved Greece and visited Delphi twice during his reign.

This is a peaceful place, filled with whispering olive trees, birdsong, and light. In this sanctuary, the traveller could take a breath and prepare him or herself for the next stage.

Within the sanctuary of Athena Pronaia, there was the larger, ‘old’ temple of Athena (built c. 510 B.C.), and the smaller ‘new’ temple of Athena (built c. 380 B.C.) where pilgrims would have made their offerings.

Today, however, the main structure that draws the eye is the tholos, the round temple that stood between the two main temples of Athena. It is not known exactly what rituals took place inside this striking temple, one theory being that its shape echoed the round huts or structures of a more ancient time. The tiled roof was accented by lion heads about the perimeter an the metopes, some of which remain, depicted the Gigantomachy (battle of the Giants) and the Amazonomachy (battle of the Amazons).

Beside the sanctuary of Athena Pronaia, there also lay the long tiled roof of the Roman gymnasium, one of the more recent additions to Delphi, where Athletes participating in the Pythian Games, or travellers seeking to stay fit, might be training.

Most people, however, would have been eager to make their offerings to Apollo in the main sanctuary up the mountainside, and have their questions answered by the Pythia. However, it was not just a matter of walking in and doing so.

One had to be purified.

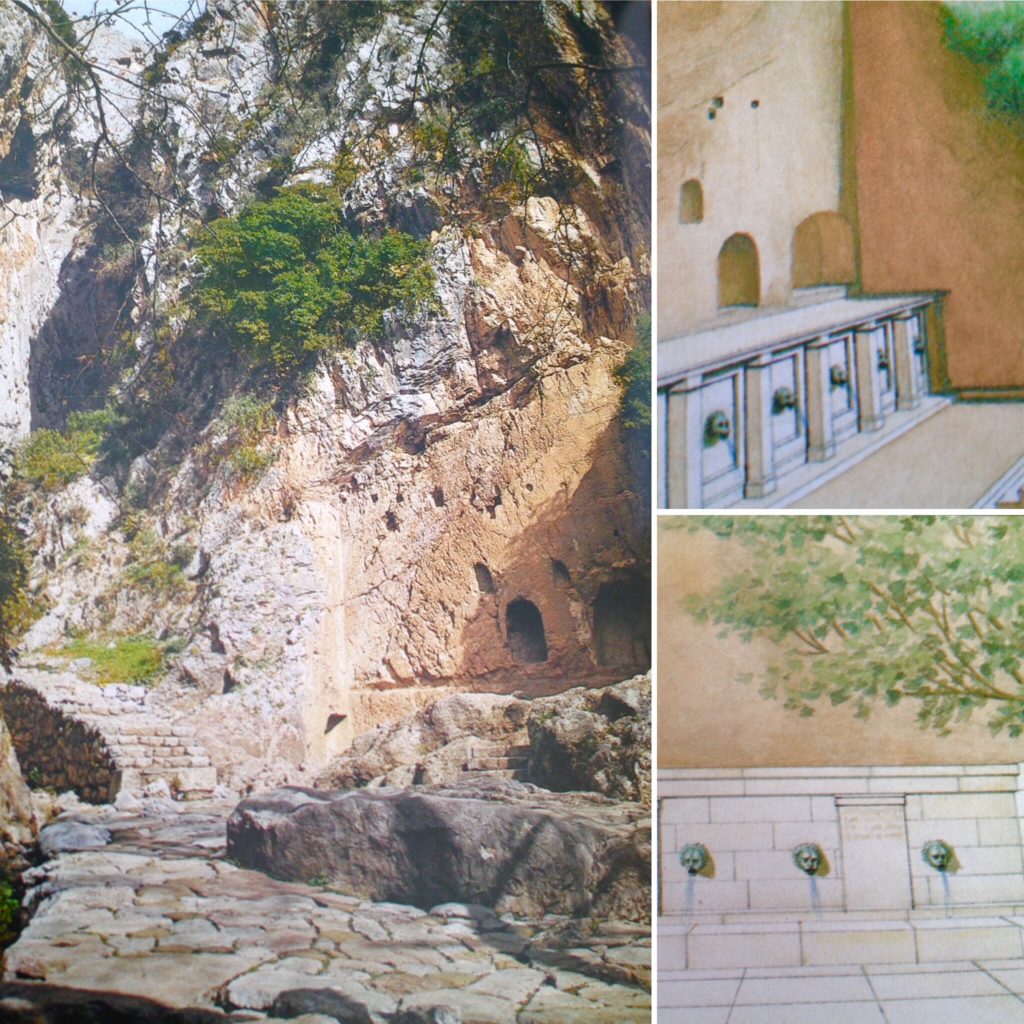

The Phaedriades, or ‘Shining Ones’ (Wikimedia Commons)

In the shadow of the twin peaks known as the Phaedriades, or the ’Shining Ones’, there lay the sacred spring of Castalia. The water that fed this spring came out from the Phaedriades and was used in the important purification rituals of Delphi. Even the Pythia purified herself with this water.

If one did not go through the purification, one could not enter the sanctuary which was about five hundred meters away. The line would have been long, especially if one arrived for the seventh day of the month.

Within a shaded court, there was a pool fed by lion-headed spouts. Stairs led down into the water where pilgrims washed their hands, face and hair with the sacred water. If one was guilty of homicide, however, the entire body needed to be washed in the Castilian spring.

The Castalian Fountain House where pilgrims purified themselves before entering the sanctuary. (Reconstruction by K. Iliakis)

Once a pilgrim had purified himself or herself, it was time to purchase offerings if you had not already brought some. Conveniently, there was an agora that the Romans had built, just before the entrance to the sanctuary of Apollo. Here there would have been small animals, votive sculptures, food and more available for purchase.

You might not have been able to see into the sanctuary yet, though you knew it was there, for as soon as one approached Delphi, there was a niggling feeling of awe and wonder that accompanied such proximity to this most holy place of Apollo’s, the place where he slew the great Python and where, ever since, heroes, kings and countries had come for his wisdom.

Once you stepped through the main gate into the sanctuary, the flow of people would have led you on.

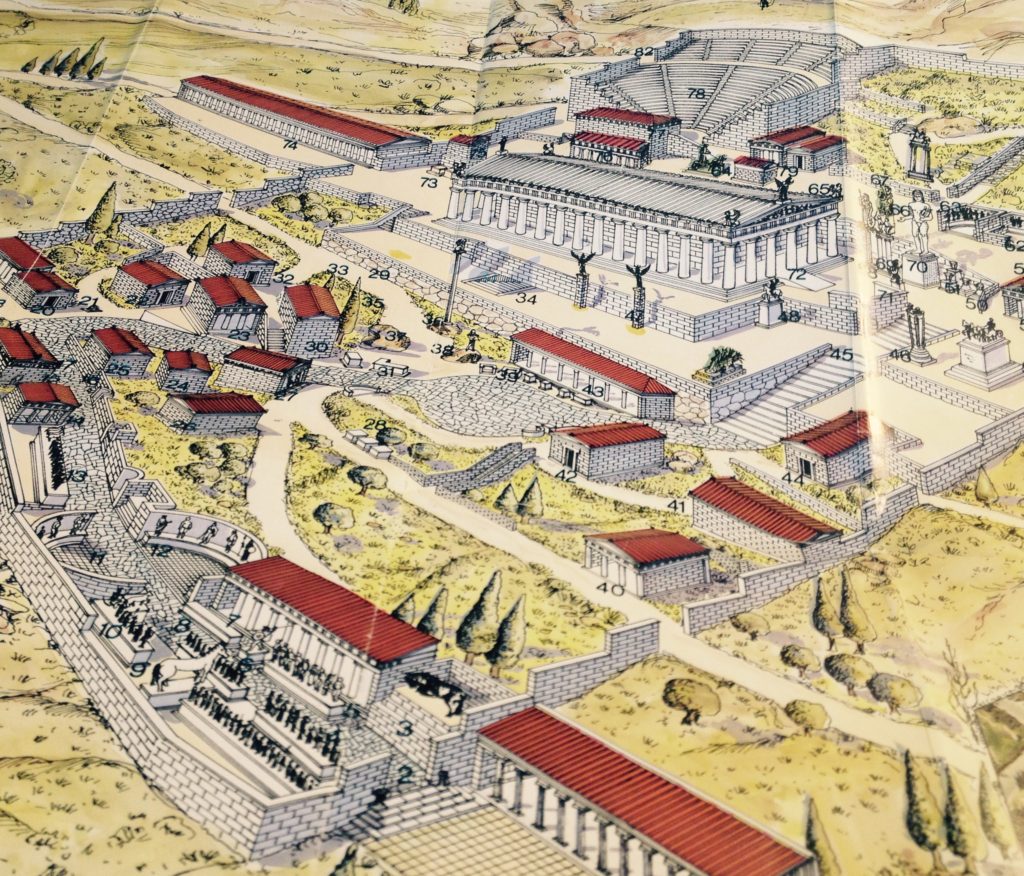

Site map of Delphi showing the Sacred Way running up through the sanctuary of Apollo to the temple itself. Reconstruction by Dimitris Kyriakos and Dimitris Nassides based on research by the French Archaeological School)

As one walked along the Sacred Way of Delphi, one would have been struck by the amount of artworks, monuments and votive offerings along the way. It would have been like walking through a filled museum for the modern traveller, which is fitting as Apollo was the leader of the Muses.

The first thing one would have seen are various statues groups that included the Bronze Bull of the Corkyrans, thirty-seven statues of the Spartan admirals, and votive statues of the Arcadians. These lined the road on both sides, and were followed by statues created by the famed sculptor, Phidias, to commemorate the Athenian victory over the Persians at Marathon.

One could have taken shelter in the shade next at the small stoa that was there alongside the votive statues of the Argive kings which were across from the wooden horse of Troy, and the statue group of the famous Seven against Thebes.

Perhaps some travellers would have stopped to look at all of the works of art, to feel the connection to an ancient past. If one was Roman, perhaps one might have felt a bit more out of place, like an intruder, or invader, there to seek the wisdom of the god you shared with the Greeks walking beside you?

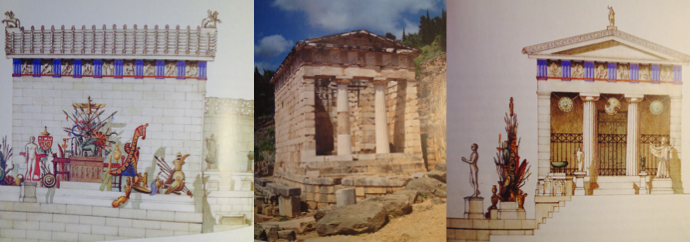

The Athenian Treasury along the Sacred Way. (Reconstructions by K. Iliakis)

The road then widened, and perhaps the crowd walking up the mountain to the main temple spread out. Next, where the road began to switch back on its way up, one came to the various treasuries where cities from across the Greek world kept riches, offerings and trophies. The treasuries of the Thebans, Beotians and Poteideans were there, squat stone structures with tiled rooftops, their doors either open to their respective citizens, or barred to outsiders.

Between the latter two treasuries was a reminder of where one was in that moment, for there was the enormous, carved omphalos stone, the ‘navel’ that told one Delphi was the centre of the world.

Then came the grand treasury of Athens with its beautiful facade and metopes depicting the deeds of Theseus and Herakles. There were banners, enemy armour and more adorning the outer steps, and riches filling the interior, there since it was dedicated to the victory at Marathon. Perhaps some were weather-worn, or perhaps Rome had already taken some, but it was nonetheless impressive, right down to the text inscribed upon the outer walls.

Continuing along the Sacred Way, one passed the bouleuterion, the Delphic council house, and the treasuries of the Syracusans and Megarians as well as other monuments and altars.

The Sybil’s Rock

If one was nervous about approaching the god with one’s question, one might have had to pause at what was seen next. In the shadow of the long temple of Apollo, which now stood above you on the next terrace, one now stood before two rocks: the rock of Leto, where Apollo slew the great Python, and the rock of the Sibyl, where the first oracle spoke Apollo’s words to the world.

What must it have been like for an ancient pilgrim to stand there, further unnerved by the gaze of the Naxian Sphinx on its ten meter column, looking down on you! Did the sound of the crowds fall away as you contemplated your purpose in being there? Could you hear the roar of the Python as Apollo loosed his arrows?

The experience was, no doubt, different for everyone.

The Naxian Sphinx in the museum at Delphi.

Past the treasury of the Corinthians and the Delphic prytaneion, the magistrates’ hall, one then mounted the Tarentine stairs beneath the great golden tripod with its thick serpent columns, a battle-offering for the Greek victory over the Persians at Plataea. To your right you would have seen another area with various large columns and votive statues of the kings Attalos and Eumenes, the stoa of Attalos which had two levels, and where people gathered to rest or talk in the shade.

This area was also dominated by the golden chariot of Helios, offered to Apollo by the Rhodians.

But your eyes would now have been drawn inexorably to your left where the colossal statue of Apollo with his lyre, and of the goddess Athena atop a soaring bronze palm stood before the temple of Apollo itself.

If it was the seventh day of the month, then perhaps it was difficult to move in the crowd of pilgrims awaiting their turn make their offerings upon the great altar of the Chians which faced the temple entrance.

The Altar of the Chians before the Temple of Apollo (Wikimedia Commons)

Would you have been frustrated to see those with promanteia – the right to see the oracle first – skip the line? These included the Delphians themselves, as well as people from Chios and some other places. If you were there, in Delphi, no doubt your questions were pressing, but there was plenty to see and do while you waited for your turn.

Looking out over the mountainside, down toward the South, the sun would have warmed your face as you gazed down on the valley of sacred, silver-leafed olive groves to the sea beyond. The sound of cicadas and birdsong might have been matched only by the hum of the gathered pilgrims.

If you still had to wait your turn to enter the temple, you could have walked up to the next terrace, above the temple, passed various columns and monuments, including the shrine to Neoptolemus, the son of Achilles. Then, to more shrines and monuments until you paused before the great bronze charioteer, and the bronze statue group of the lion hunt of Alexander the Great, dedicated by his general Crateros.

The Charioteer of Delphi

Up the hill there was another enclosure that included the rock of Kronos and the meeting hall of the Cnidians, but you had no need to go there, for you were drawn by the sound of music coming from the great theatre of Delphi which rose up the mountainside to your right. Perhaps musicians were practicing for the coming Pythian Games, or perhaps a lone poet was practising his recitation before an empty theatre, a solo offering to the ears of Apollo himself?

The Stadium farther up the mountain from the sanctuary was the site of the Pythian Games and seated up to 7000 spectators

Along the path from the top of the theatre, on into the pine-scented air of Parnassus, the stadium stretches away. Athletes are training there, running, throwing the discuss, testing their strength and skill against each other. Or perhaps they are sitting in the sun gazing up at the trees and rocky slopes above?

You think about going to watch, but then your name is called. It is your turn to see the oracle.

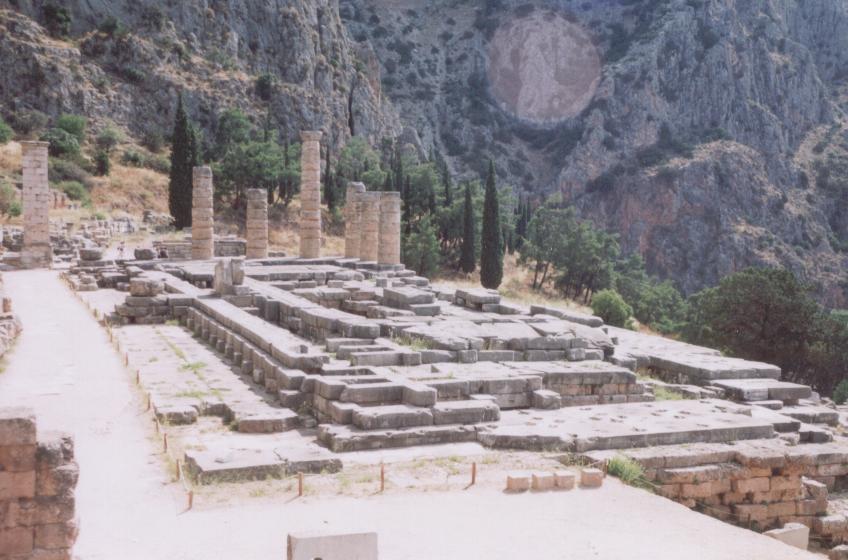

The Temple of Apollo

The temple of Apollo is the focus of the entire sanctuary. It is the home of the god. As one approaches it, perhaps one feels nervous anticipation? You are, after all, going to step into the presence of Apollo. You don’t want to get things wrong either, for then your journey might be wasted.

After you have cleansed yourself with Castalian water, you might walk up to the altar before the temple to make your offering of pelanon, the honeyed bread that all pilgrims give. You would give money too, the amount dependent upon your financial state. And then, you would offer a goat, the preferred blood offering. This act would have awoken a sense of morality in you, and you pray that when the cold water is poured over the animal, it shivers a suitable amount, for if it does not, then there will be no prophecy for you.

The Temple of Apollo at Delphi (reconstruction by K. Iliakis)

Once your offering have been made and accepted, you are told by the priests that you may make your way into the temple.

The time has come.

First you pass through a small forest of columns and the pronaos of the temple where the words of Delphi’s famous maxims arrest you.

‘Know thyself’

‘Nothing in excess’

‘Surety brings ruin’

Do you doubt yourself as you step into the temple? Are you guilty of the hubris the Gods so despise in mortals?

How many people turned away at this point, unable to step further?

You can read all about the Delphic Maxims by CLICKING HERE.

But you step into the temple, as sure of yourself as you can be, and your eyes are treated to some of the most beautiful works of art you have seen, frescoes, votive objects such as musical instruments, kraters, gilded tables, chariots, weapons, crowns and more, all offered to Apollo. There is even the iron throne that was where the great epinikion poet, Pindar, sat when he recited his words to Apollo at Delphi.

And that saying, in these fortunate circumstances, brings the belief that from now on this city will be renowned for garlands and horses, and its name will be spoken amid harmonious festivities. Phoebus, lord of Lycia and Delos, you who love the Castalian spring of Parnassus, may you willingly put these wishes in your thoughts, and make this a land of fine men. All the resources for the achievements of mortal excellence come from the gods; for being skillful, or having powerful arms, or an eloquent tongue. As for me, in my eagerness to praise that man, I hope that I may not be like one who hurls the bronze-cheeked javelin, which I brandish in my hand, outside the course, but that I may make a long cast, and surpass my rivals. Would that all of time may, in this way, keep his prosperity and the gift of wealth on a straight course, and bring forgetfulness of troubles. Indeed he might remember in what kind of battles of war he stood his ground with an enduring soul, when, by the gods’ devising, they found honour such as no other Greek can pluck, a proud garland of wealth.

(Pindar, Pythian 1, For Hieron of Aetna)

Pindar

Beyond the piles of offerings about you, and the other maxims inscribed upon walls and plaques, there is a wood and ivory screen that separates the first room of the temple from the cella.

One of the priests ushers you through the screen, and on the other side you see the main altar where Apollo looks down upon you. At the god’s feet is the pythomantis, the eternal flame that is always tended by the Pythia and the Hestiades, the five chosen Delphic maids who continually feed the flames with fir wood from the mountainside.

The temple smells strongly of smoke, of oil and burning wood, but there is another smell you cannot discern, something slightly foul coming from a chamber beneath the cella.

Besides the Delphic maids, there are three priests of the oracle, and the five holy men descended from Deucalion, whose ark landed on Parnassus during the Great Flood.