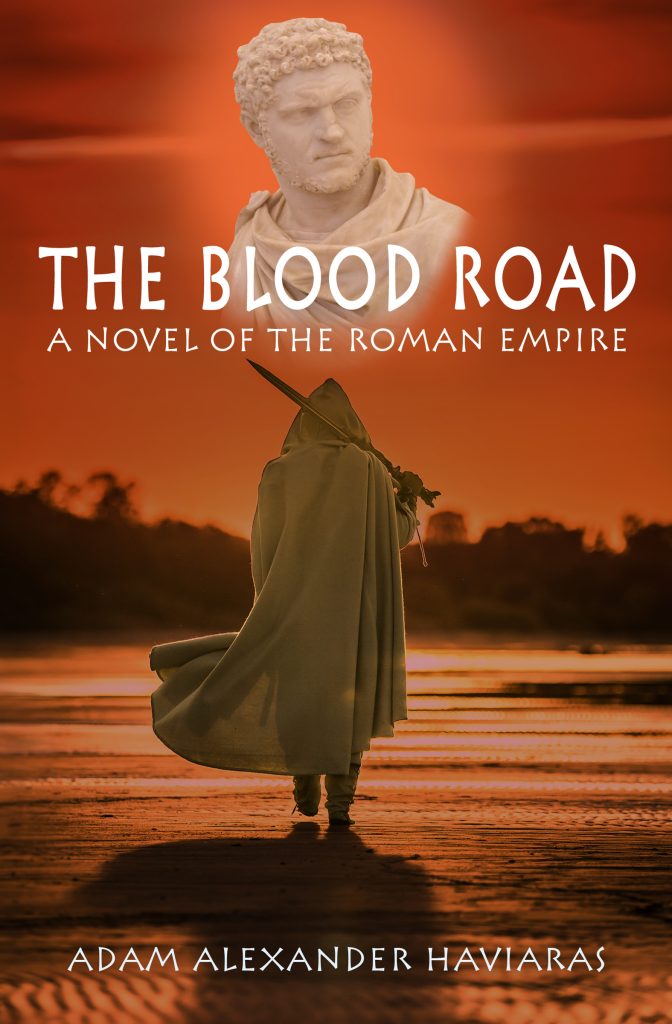

Salvete Romanophiles!

We’re back for another post in The World of The Blood Road blog series in which we look at the history, people and places that are involved in the latest Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy novel.

If you missed the previous post on the Constitutio Antoniniana, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In Part IV, we’re going to be taking a brief look at what may have been the most elite fighting force in the history of the Roman Empire: the Praetorian Guard.

Hope you enjoy!

Praetorian Guard officers

Throughout the Eagles and Dragons series, members of the Praetorian Guard and their prefects play a key role in what is happening in the empire, and are often involved in the court intrigues that accompany the imperial entourage. However, this is not just the case in fiction.

The Praetorian prefects and their troops were often at the heart of imperial affairs, wielding tremendous power and influence. They had the ability to make or break emperors.

When we hear the word ‘Praetorian’, it’s difficult not to think on some of the most infamous prefects in history such as Lucius Aelius Sejanus who conspired against Emperor Tiberius, or Quintus Naevius Sutorius Macro, who may have ordered the death of Tiberius and then put Caligula on the throne. Or how about Pescennius Niger, who made his play for the throne against Septimius Severus and lost after being prefect for a year under Commodus? There were also some prefects who went on to even greater heights such as Titus Flavius Vespasianus, the future Emperor Titus, who served as prefect under his father Vespasian.

In the Eagles and Dragons series which takes place during the reigns of Septimius Severus and Caracalla, we see how powerful and dangerous Gaius Fulvius Plautianus and Marcus Opellius Macrinus were, and how influential the jurists Papinianus and Ulpianus were.

There is a long list of Praetorian prefects throughout the history of the Roman Empire, some excellent and loyal, others power hungry and willing to do whatever it took to consolidate the great power and wealth to which they had access.

But who exactly were the Praetorian Guard and how were they organized? We’ll take a brief look at their history next.

Emperor Augusts

The name of the Praetorian Guard comes from the small group of men who, during the Republic, would accompany magistrates, or praetors, on campaign.

After the murder of Julius Caesar in March of 44 B.C., Marcus Antonius created a personal Praetorian guard detail for himself made up of six thousand legionaries.

But it was Emperor Augustus who really formalized the Praetorian Guard around 27 B.C. when he adapted this idea to create an Imperial Guard. The Praetorians were mainly charged with ensuring the ruler’s security, but there were other duties as well.

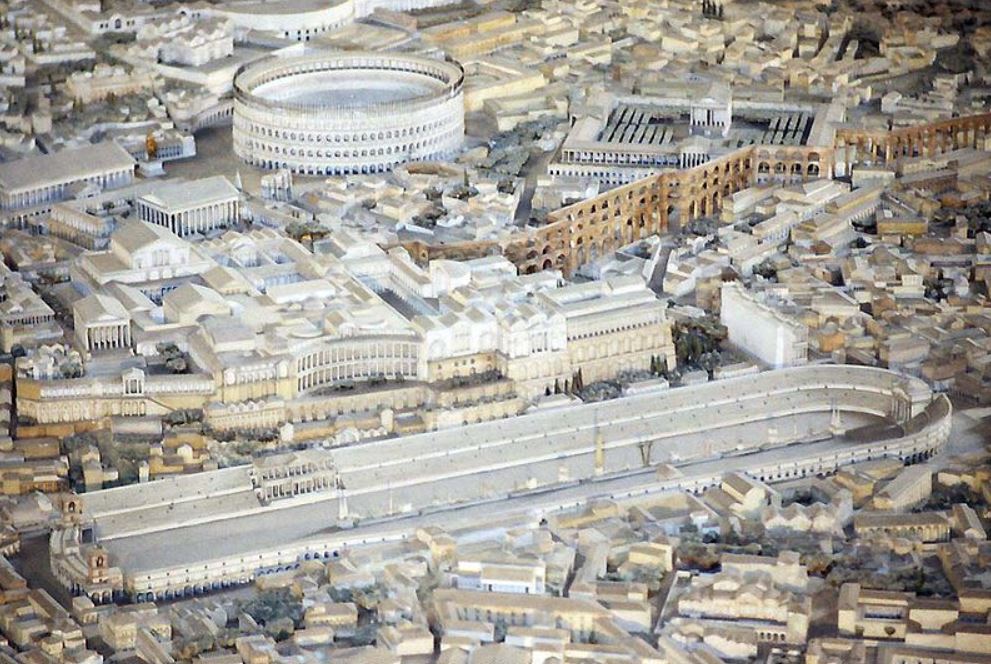

The Praetorians and their prefects were also responsible for sentry duty at the palace, and escorting the emperor and his family members. They acted as a sort of riot police in Rome, standing guard over events such as at the Circus Maximus, the Colosseum and the theatre. They operated the city prison and carried out executions in Rome, especially of high status prisoners. The Praetorians were also a sort of political and secret police.

One might think that the Praetorians had it easy compared with legionaries who were constantly fighting on the front lines of the Empire, and you would be right. But they could also fight, and sometimes they did when the emperor went on campaign. They excelled at this too.

The Praetorian Guard were the elite of Rome’s military might.

The Praetorian Guard (Illustration by Peter Dennis)

When the Praetorians were first formed, the men had to be Italian, from Latium, Etruria, and Umbria, and later also from Cisalpine Gaul and other territories. Men were recruited between 15 and 32 years of age.

In Rome especially, the Praetorians were seen as a military force that was used to enforce the will of the emperor upon others. They discouraged plotting and rebellion, that is, unless they were doing it themselves. And because they could create or destroy emperors and were, at times, the true power in Rome, the post of Praetorian Prefect naturally attracted power-hungry men such as some of those named above.

There are several instances where the Praetorians went too far, one being the auctioning of the imperial throne after the death of Commodus.

When Septimius Severus emerged the victor after the subsequent civil war, he made sure to replace the entire Praetorian Guard with men from his own legions, men whose loyalty could be relied upon. His one mistake was, as other emperors had also done, trusting the wrong person in the position of Praetorian Prefect.

Model of ancient Rome with the Circus Maximus in the foreground

In spite of the air of corruption, or perhaps because of it, many men aspired to be a part of the Praetorian ranks. Apart from the power, there are other reasons why the Guard attracted men. It was just a better gig!

First of all, Praetorians had a shorter term of service before they could retire. They served for 16 years, whereas legionaries had to serve for a minimum of 20. They received much better pay as well. For example, in about A.D. 14, a Praetorian guardsman would have received 720 denarii per annum, compared with a legionary’s 225 denarii. Upon retirement, Praetorians received a bonus of 20,000 sestercii, and legionaries received 12,000 sestercii.

One reason that has been suggested for the difference in pay is that Praetorians probably had fewer opportunities to loot since they were not on campaign as much as regular legionaries. Whether or not this is true, it seems like being a Praetorian was just a more desirable deal, and many legionaries were jealous of their lot.

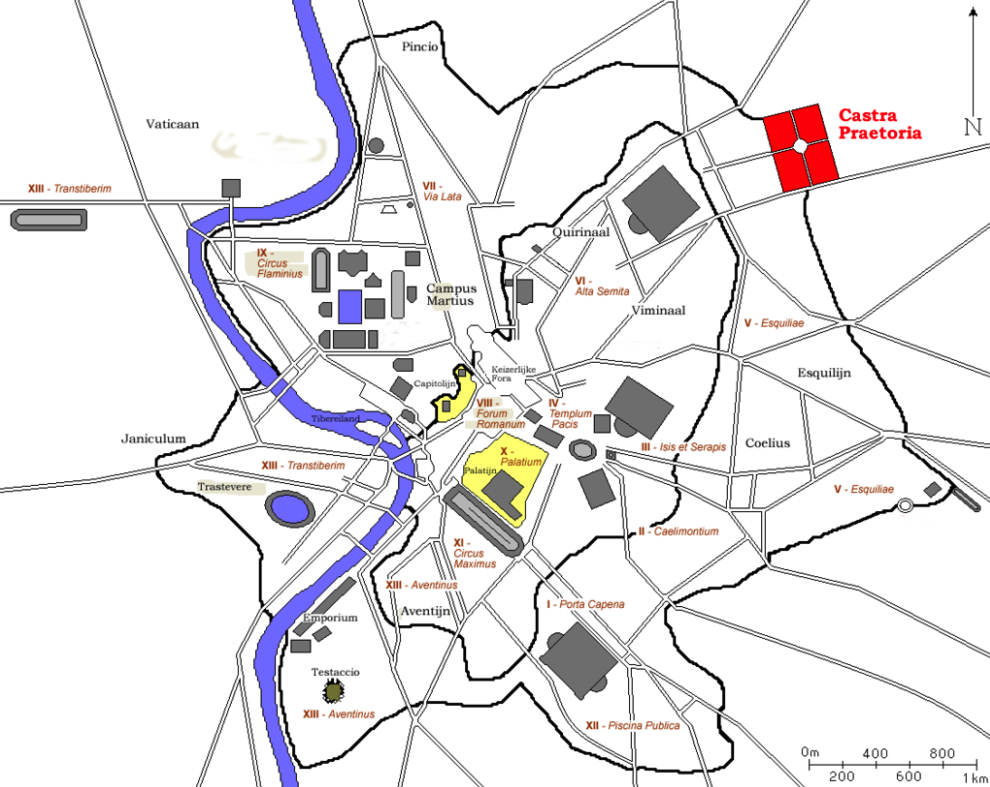

The Castra Praetoria and ancient Rome (Wikimedia Commons)

Despite their differences, however, the Praetorian Guard had a similar makeup to the legions.

There were nine cohorts, each led by a tribune and six centurions. The tribunes reported to the Praetorian Prefect. There was also a princeps castrorum, or ‘camp prefect’, and a head centurion, or trecenarius, who was equal in status to the tribunes, and who commanded 300 speculatores, who served as cavalry scouts or Praetorian spies.

There has been some disagreement among scholars about the number of troops in the Praetorian cohorts. Some believe it was 500, and others 1000. But during the reign of Severus, the number of troops in a Praetorian cohort was 1000 men.

Originally, there were two Praetorian prefects at a time who supervised the Guard, but during the reign of Tiberius, the emperor appointed just one, Sejanus, and he became very powerful indeed. Severus made the same mistake with Plautianus.

It was around A.D. 20-23 that Emperor Tiberius and Sejanus really solidified the power of the Praetorians, and gave the Guard a power base from which it could operate: the Castra Praetoria.

Until the reign of Severus, who stationed his II Parthica legion at Albanum, the Praetorian Guard was the only military unit permitted by law to be stationed in Italy itself.

The Castra Praetoria at Rome was their fortress.

This 17 hectare (40 acre) fortress, with a training ground beside it, was built around A.D. 23 by Tiberius and Sejanus. It was originally located outside of the Servian walls of Rome on the Viminal hill, which included the Esquiline plateau. Much of the walls still stand today, and house a modern garrison of the Italian army.

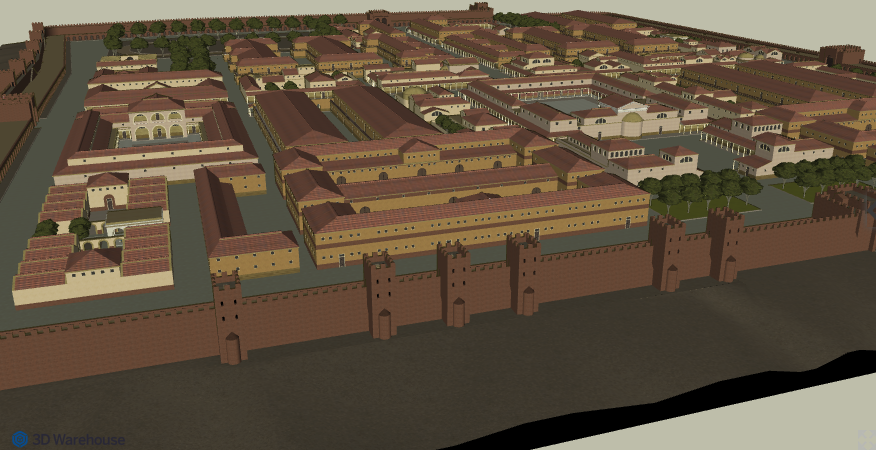

The Castra Praetoria was smaller than a full legionary castrum, but it is believed that with the presence of barracks around the walls, and of two-storey barrack blocks within, the capacity may have been as much as 12,000 troops!

That is quite a force of men within Rome!

The walls were of concrete and brick and at first measured 3.5 meters high. They were heightened by the Praetorian prefect, Macrinus, during the reign of Caracalla (A.D. 211-217). In A.D. 271, Emperor Aurelian built new walls around the city of Rome and at that time incorporated the Castra Praetoria into them, again raising the height of the fortress walls, and also adding towers and battlements.

In A.D. 310, Maxentius raised the walls even more to prepare for the coming confrontation with Constantine.

The Castra Praetoria today (Wikimedia Commons)

Because the Praetorians had been at the heart of so many conspiracies and plays for power over the years, emperors such as Severus sought to punish them severely or replace the Guard altogether.

After Constantine the Great defeated Maxentius at the battle of the Milvian Bridge in A.D. 312, Constantine went one step further to finally put an end to the machinations of this powerful and often corrupt military force. He demolished the inner wall of the Castra Praetoria, and dissolved the Praetorian Guard for good. From that time on, the role of Praetorian prefect became a purely administrative role.

Arch of Constantine, Rome

The history of the Praetorian Guard is fascinating, as is the behaviour of the Praetorian prefects who held the post over the roughly 300 year history of the Guard.

In the Eagles and Dragons series, which takes place during the reigns of Severus and Caracalla, the power and influence of the Praetorians and their prefects is at the centre of the political intrigues behind-the-scenes.

This post has but scratched the surface, but I hope that you have learned a bit more about this force of Rome’s elite soldiers at the heart of the Empire.

Keep a lookout for Part V in The World of The Blood Road blog series when we will be taking a look at the Iberian city of Carthago Nova.

Thank you for reading.

The Blood Road is available on-line now in e-book and paperback at major retailers. CLICK HERE to get your copy. You can also purchase directly from Eagles and Dragons Publishing HERE.

If you are new to the Eagles and Dragons historical fantasy series, you can check out the #1 best selling prequel, A Dragon among the Eagles for just 1.99 HERE.

Hi Adam, Thank you for this intriguing post about the Praetorian Guards , a powerful force indeed. No wonder the soldiers were anxious to join the Praetorian guard for the better pay and other perks which went with the post. I am eagerly awaiting The Blood Road book which my niece has ordered for me I think it has to come via Athens to Crete where I live. Once I have read it I will most certainly put a review out for you and let you know my thoughts. Best wishes, have a great weekend and stay safe.

Hi Rita! So good to hear from you 🙂 I’m glad you enjoyed this post and that your copy of The Blood Road is making the voyage your way. Based on my own experiences of late, I think Hermes has taken a break from the Greek postal service during the pandemic! As ever, thank you for your comment, and I do hope all is well with you on beautiful Crete! Giassou!

I love reading your books, and Simon Scarrow too (sorry!) but there is one thing that seems very true to me, though the names may change, politics doesn’t; from ancient Rome to modern Europe, politics is a dirty game and power is sought by people who really aren’t suitable.

These blogs are brilliant too, an insight into a world that always intrigues me.

Thank you for the kind words, David! So glad you have enjoyed the books and the blog series. And no need to be sorry! Simon Scarrow’s books are brilliant 😉

It is true, some things don’t change, politics among them. It might be a bit of a cliche but if more people studied ancient history, we could certainly avoid repeating a load of mistakes over…and over…and over again. Cheers!