Part I – The Antonine Wall

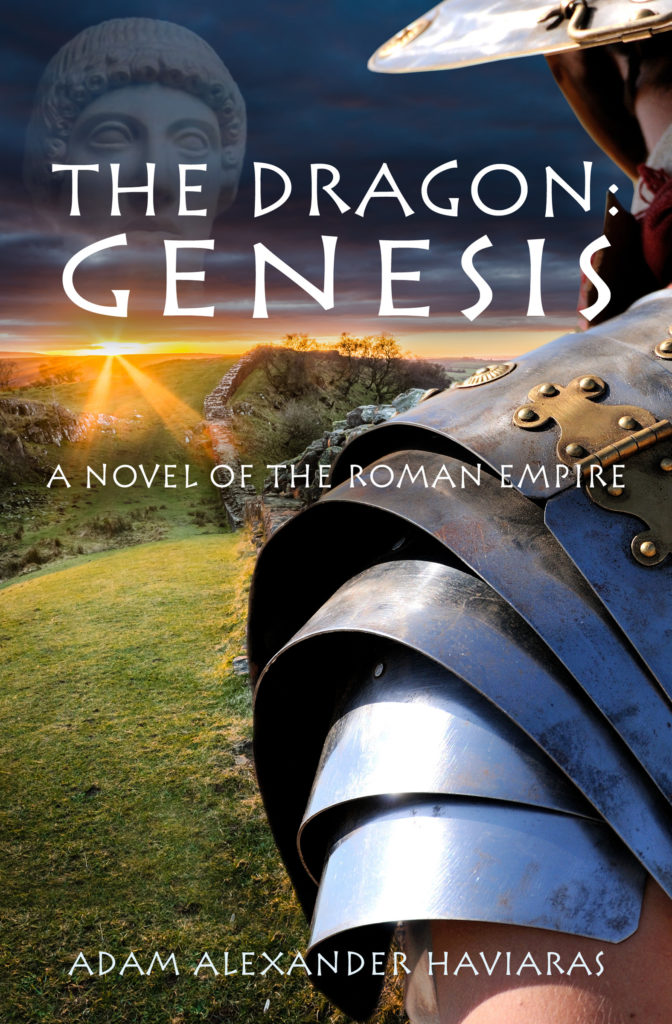

Welcome to Part I of this new blog series celebrating the release of the latest Eagles and Dragons series novel The Dragon: Genesis.

In this blog series, we’ll be sharing the research that went into the novel with you, looking at the history, settings, themes, and historical personages that are related to the story which takes place during the second century A.D.

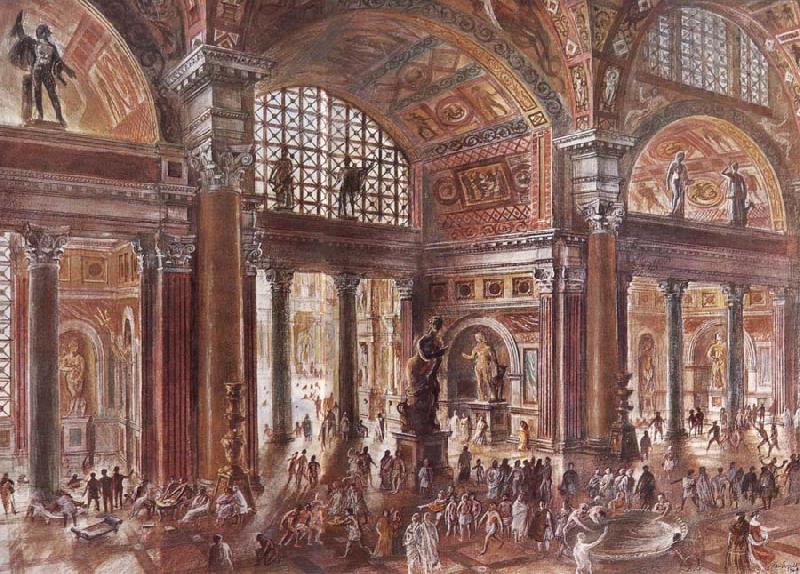

When we think of the Roman Empire, what often comes to mind is the image of marching legions spreading out over the world. We also conjure images or memories of great ruins on the edges of Rome’s empire such as the massive amphitheater at El Jem in Tunisia, or the ruins of temples and other constructs that dot the European, Middle Eastern, and North African landscapes.

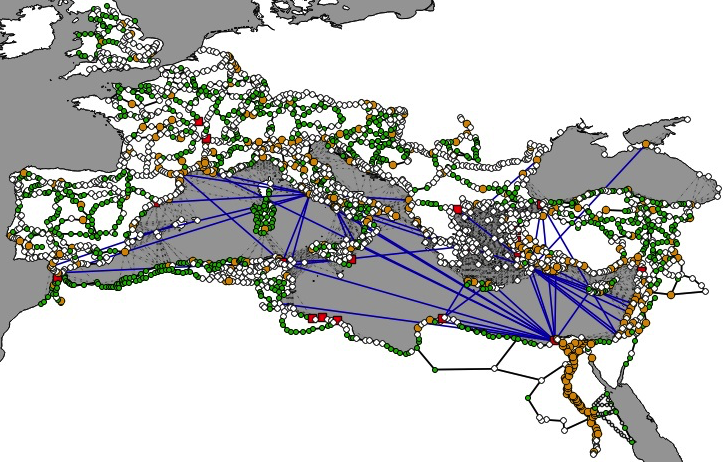

Roman frontiers were vast, stretching thousands of kilometers and encompassing many lands and peoples over time. These frontiers are perhaps what many think of when it comes to the Roman Empire, and none more so than Hadrian’s Wall, the great stone frontier fortification built by Emperor Hadrian in northern Britannia in the 120s A.D. It stretched 73 miles from modern Carlisle to Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and marked a decisive edge of the Roman Empire.

There was, however, another wall.

Approximately 100 miles to the north of Hadrian’s Wall, in modern Scotland, lie the somewhat less romantic, but highly significant, ruins of the Antonine Wall, another frontier of the Roman Empire, and an important cultural and heritage landscape today.

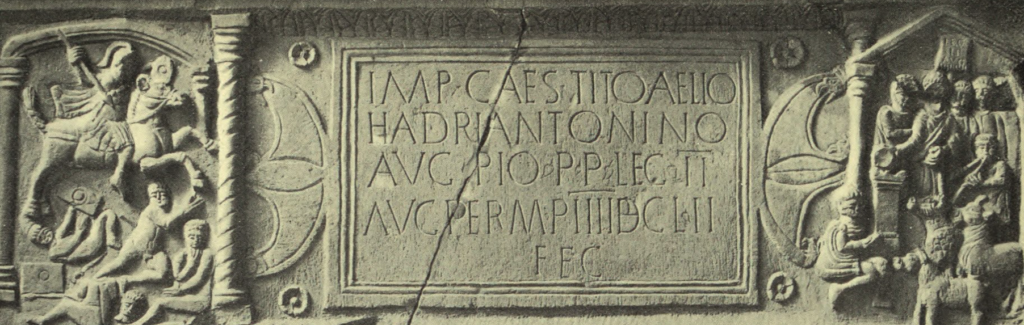

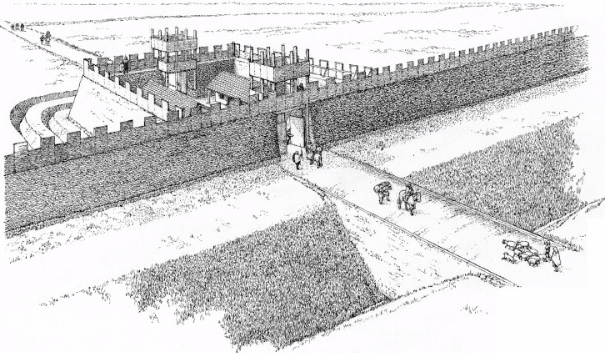

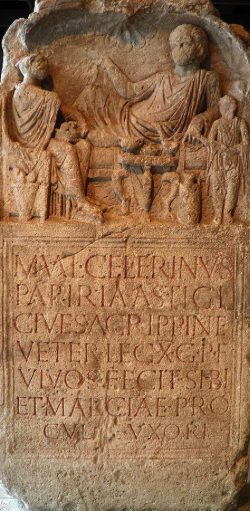

In the early 140s A.D., the emperor Antoninus Pius (A.D. 138-161) ordered a new frontier to be built in Caledonia. It was a massive building project, and the work was undertaken by the men of three legions: the II Augustan from Isca (Caerleon), the VI Victrix from Eburacum (York), and the XX Valeria Victrix from Deva (Chester). Until the forts and fortlets were constructed, the troops would have lived in tents in temporary camps, and among their numbers would have been specialists such as surveyors, masons, carpenters and many more.

At the outset, overall responsibility for the building project was given to the governor of Britannia at the time, Quintus Lollius Urbicus.

The purpose was, perhaps, two-fold: to attempt to push Rome’s permanent frontier father north, but also to hold back the warlike tribe (perhaps a confederation of tribes) we know as the Caledonii.

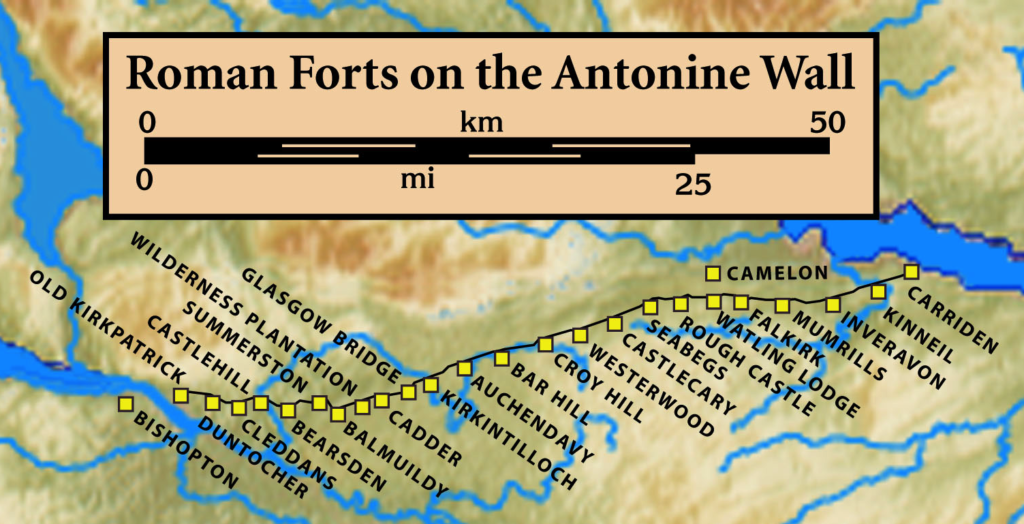

The Antonine Wall may be smaller in scale to Hadrian’s Wall, but it is still an imposing construction. It was 39 miles long, stretching from the Firth of Clyde in the West (near Glasgow) to the Firth of Forth in the East (near Edinburgh). It cinched the belt of Scotland.

But this was not just a wall! It was a manned frontier of the Roman Empire.

The Antonine Wall consisted of about seventeen forts and approximately 9 smaller fortlets every 2 miles, including two coastal forts at either end. The garrison of this frontier was in the range of 6000 to 7000 troops. This included legionaries, but the garrison was mainly comprised of auxiliary troops once the wall was complete.

Despite its importance, why isn’t the Antonine Wall as well-known as Hadrian’s Wall?

Part of the reason for this is that its ruins are less prominent. Less has survived.

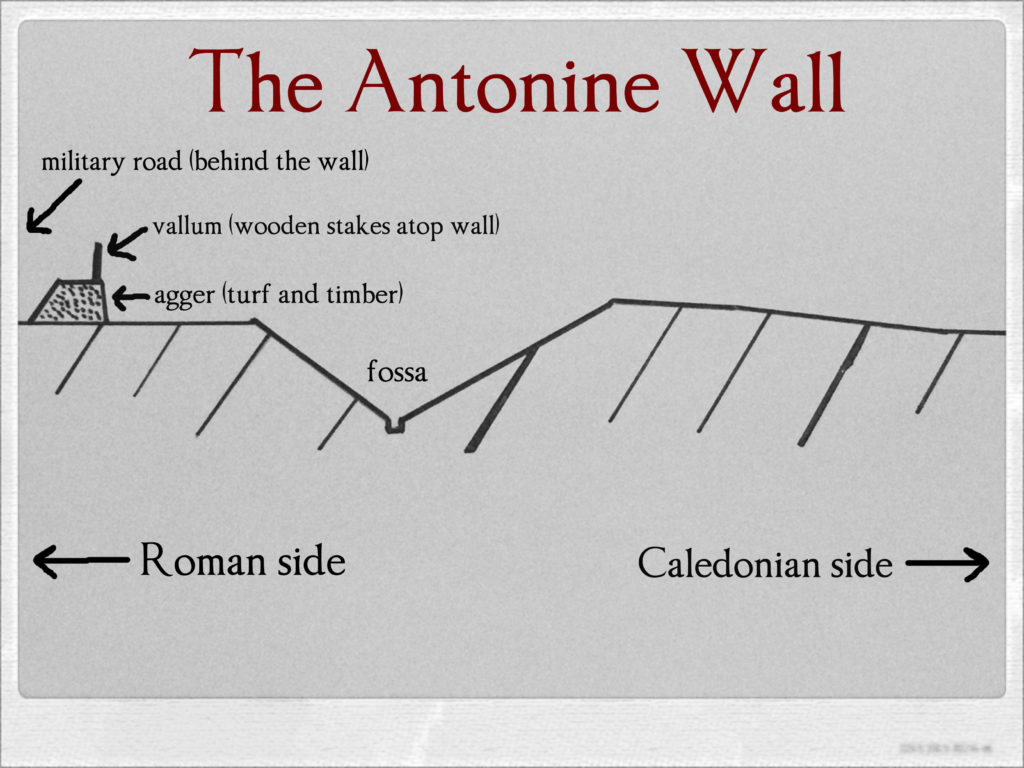

The Antonine Wall was not built of stone on the imposing scale of Hadrian’s Wall. It was a turf and timber wall built on a stone foundation. For this reason, today the remains mostly consist of a grassy embankment, 13 feet high, that was part of the ditch (fossa) located to the north the wall. The wall itself consisted of a turf embankment (agger) topped by a wooden battlement or barricade of sorts (vallum) behind the ditch. You can read more about the specifics of Roman defences HERE.

Unlike Hadrian’s Wall, which had ditches, or fossae, in front and behind, the Antonine Wall had but one fossa in front. It also had a military road running the length of the wall behind it so as to allow for quick, efficient movement of troops and supplies along the way, as well as the relaying of commands and news.

When completed, the Antonine Wall would have been an imposing defensive line in Caledonia. Interestingly, it was not the first such network.

There was a defensive line of forts from the Agricolan invasion of Caledonia in the first century A.D. that pre-dated both Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall. This frontier is known today as the Gask Ridge, and many of the forts along this first frontier were refortified during the Antonine period.

The Antonine Wall joined up with the Gask Ridge frontier roughly at the fort of Camelon, and together, the two frontiers further hemmed the Caledonii in on the highlands.

To read more about the Gask Ridge frontier, which is the setting for the novel Warriors of Epona, CLICK HERE.

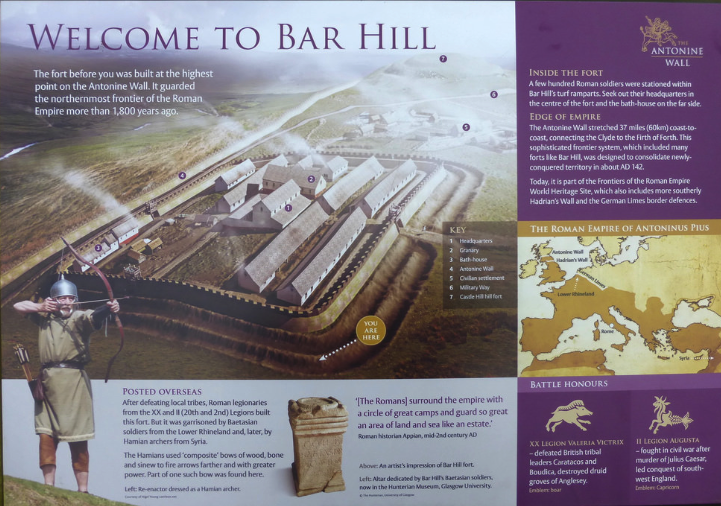

Signage at Bar Hill fort site showing reconstruction of the fort. Bar Hill fort was the highest point along the Antonine Wall.

The novel The Dragon: Genesis begins during construction on the Antonine Wall, specifically at the site of Bar Hill fort which was the highest point of the wall. This fort had commanding views from its vantage point, and it was one of the larger forts along the wall, complete with principia, or headquarters building. It is interesting to note that the fort here was not flush with the wall like some others, but rather was set back, just south of the military road.

The location of this fort made it the ideal place to start the novel.

It is perhaps an attestation to the resistance put up by the tribes of Caledonia that the Antonine Wall was abandoned in A.D. 162, just twenty years after construction began.

It lay in this state of abandonment until about A.D. 208 and the Severan invasion of Caledonia. At that time the Antonine Wall and many of the Gask Ridge frontier forts were re-garrisoned. To read more about the Romans in Scotland, CLICK HERE.

After the two phases of the massive Severan invasion of Caledonia, the Antonine Wall became silent once more, the frontier moving back again to Hadrian’s stone construction.

Today, you can visit the remains of the Antonine Wall on any number of walks to visit the locations of several of the forts listed on the map above, including the fort at Bar Hill. It really is an amazing landscape with many fascinating sites along the way. It’s no wonder that in 2008 it was officially given World Heritage Site status by UNESCO as part of the ‘Frontiers of the Roman Empire’.

To read a lot more about the Antonine Wall and the individual forts that are a part of it, be sure to check out the official website HERE.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this first part in The World of The Dragon: Genesis.

In Part II of The World of The Dragon: Genesis, we’ll be looking at the cursus honorem in ancient Rome.

Thank you for reading.

Part II – The Cursus Honorem in Ancient Rome

What was the cursus honorum?

Literally, it meant ‘the course of honours’, and it referred to the sequence of official offices in the career of a Roman politician.

Late in the sixth century B.C., when Rome became a Republic, it was run (some might say ‘ruled’) by various magistrates who would form the members of the senate of Rome.

With the rise and rule of military commanders such as Sulla, Pompey, and Caesar, the magistracies of the Roman Republic became less effective, but they remained a prestigious goal for most.

From the third century B.C., there developed a specific track for a senatorial career – the cursus honorum.

In 180 B.C. a law was proposed by the tribune of the Plebs, Lucius Villius Annalis, which set down the rules and age limitations for the cursus honorum and, to an extent, perhaps sought to curb the ambitious young men of Rome.

In Tacitus’ Annals, we see reference to the law and the changes that had occurred within the cursus honorum:

With our ancestors, office had been the prize of merit, and all citizens who had confidence in their qualities could legitimately seek a magistracy; nor was there even a distinction of age, to preclude entrance upon a consulate or dictatorship in early youth. The quaestorship itself was instituted while the kings still reigned, as shown by the renewal of the curiate law by Lucius Brutus; and the power of selection remained with the consuls, until this office, with the rest, passed into the bestowal of the people. The first election, sixty-three years after the expulsion of the Tarquins, was that of Valerius Potitus and Aemilius Mamercus, as finance officials attached to the army in the field. Then, as their responsibilities grew, two were added to take duty at Rome; and before long, with Italy now contributory and revenues accruing from the provinces, the number was again doubled. Later still, by a law of Sulla, twenty were appointed with a view to supplementing the senate, to the members of which he had transferred the jurisdiction in the criminal courts; and, even when that jurisdiction had been reassumed by the knights, the quaestorship was still granted without fee, in accordance with the dignity of the candidates or by the indulgence of the electors, until by the proposition of Dolabella it was virtually put up to auction. (Tacitus, Annals, Book XI)

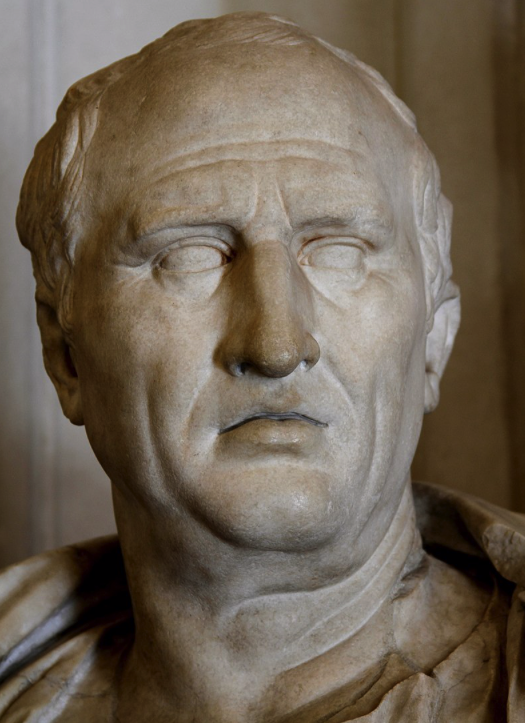

But the proposed law, the Lex Villia Annalis, was not without its opponents, and over time, more and more young men opposed the restrictions it imposed on the cursus honorum. Many disregarded its precepts and found ways around it. Some of the men who did this were Scipio Aemilianus, Gaius Marius, Pompey, and perhaps one of the most famous men to rise along the cursus honorum, Marcus Tullius Cicero, who is supposed to have achieved each level at the youngest possible age.

But what exactly did the cursus honorum entail? What was its purpose, and how did things work?

It is actually quite complex in the details, but we will now seek to look briefly at these questions to gain a better understanding.

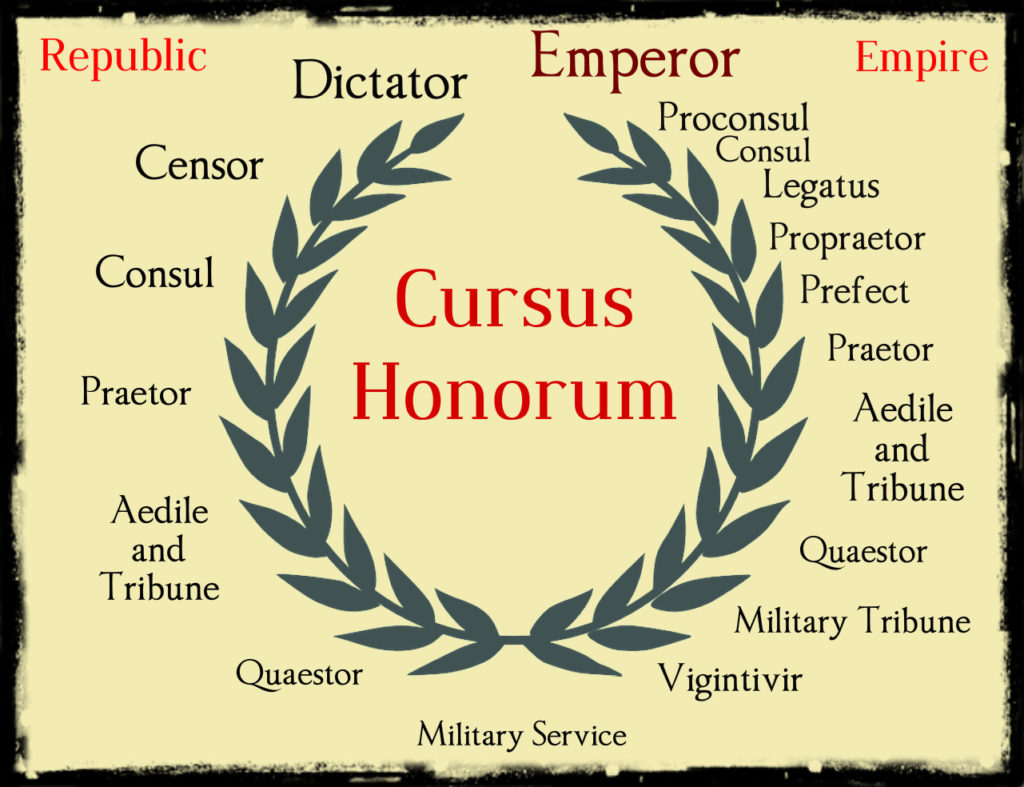

General representation of the steps along the cursus honorum during the Republican and Imperial periods. (image: Eagles and Dragons Publishing)

The cursus honorum gave men with political aspirations a chance to work and prove themselves at various levels of government after their general military service. Because it evolved over time, there was a difference between the cursus honorum in the Republic versus the Principate (Imperial Age).

During the Roman Republic, the cursus honorum was a path open to men of the senatorial class. After one’s military service, the positions in order of ascendency were as follows:

Quaestor: twenty financial and administrative officials in charge of public records and the treasury (aerarium). They were also paymasters for the army, accompanying generals on campaign. This was a required post for those seeking to enter the Senate. The minimum age was 30 years.

Aedile: there were four patrician aediles who administered the temple of Ceres, and later were placed in charge of public buildings, archives, and later, public games. The minimum age was 37 years.

Tribune: ten tribunes were elected from the plebeian class, and their role early on was to protect this class from the patricians. They were directly responsible to the people’s assembly and had similar duties to other magistracies. They had a veto power in the city of Rome. The minimum age was 37 years.

Praetor: the praetors of Rome were the men who originally replaced the king. There were eight of these, and their role was to administer the law at Rome. They were, at first, the supreme civil judges. Later, they were to deal with legal cases with foreigners, and as Rome acquired more territories, more praetors were required. The minimum age was 40 years.

Consul: with the abolishment of the kings in 509 B.C., there were two magistrates at a time who were elected to this position. They had the duties of the king, but did not have supreme power. At first, they were only of the patrician class, but in 367 B.C., plebeians could stand for the office. Elections were held on the Ides of March (the 15th). The minimum age was 43.

Lastly, and not strictly a post required for the cursus honorum, the role of dictator was one that was granted by the Senate, through the consuls, during times of emergency. The dictator had supreme military and judicial authority, but other magistrates retained their offices during a dictatorship. It was usually granted for six months. After Julius Caesar’s murder on the Ides of March in 44 B.C., the office of dictator was abolished.

Ruins of the Basilica Julia (right of centre), one of the main public buildings, in the Forum Romanum

Now that we have looked briefly at the cursus honorum during the Republic, let us look at the course of honours during the Empire.

During the early imperial period, the cursus honorum was extended with a series of new posts being inserted between the offices of quaestor, aedile, praetor, and consul, which were retained. The role of senators was diminished, and they came to take on a more administrative role beneath the emperor. It is also important to note that the age requirements for posts were reduced, reflecting previous opposition to the old restrictions.

Here are the main positions along the cursus honorum during the Empire:

Vigintivir: there were twenty vigintiviri and these were minor magistrates who worked on various portfolios such as the mint for which perhaps only three of them would have charge of at a time. This position was the new stepping stone to get onto the cursus honorum path. The minimum age was 18 years.

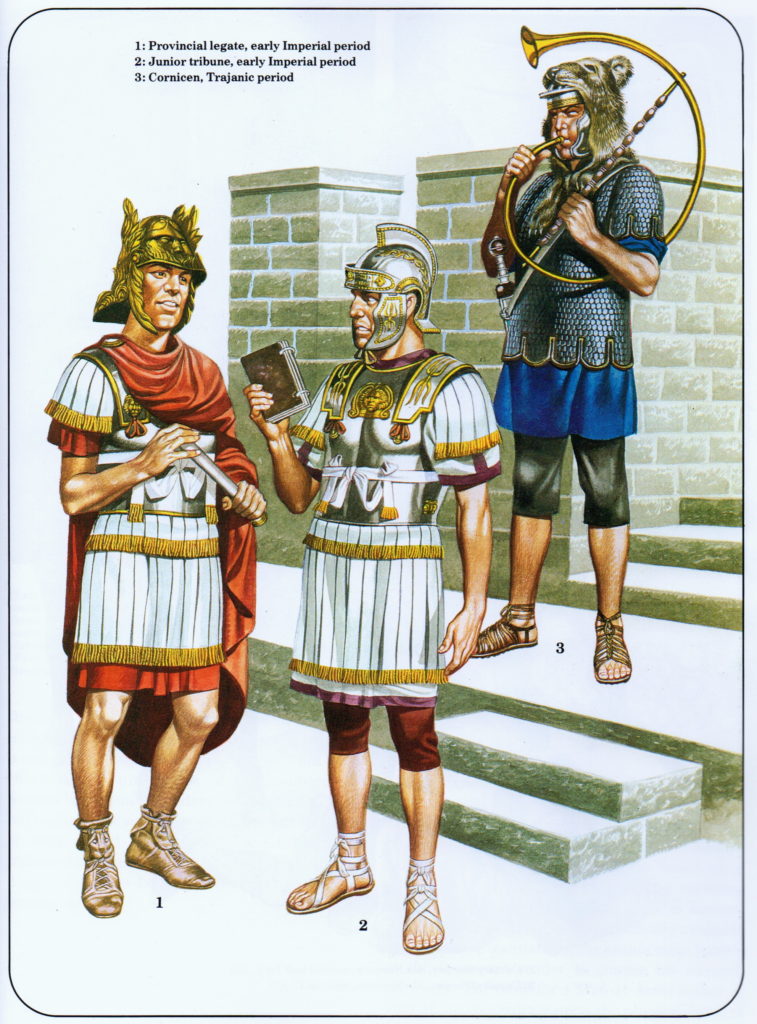

Tribunus Angusticlavius: the role of tribune during the Empire took on a more military role, with the emperors assuming the previous tribunician powers wielded by the tribunes of the Plebs during the Republic. This was one open to Equestrians (more on this class shortly), and there were five of these junior tribunes assigned to each Roman legion. The position remained until the fifth century A.D., and was another important step on the cursus honorum. The minimum age for a military tribune was 20 years.

Quaestor: during the Empire, the number of quaestors increased as the empire itself grew in size, and though their functions might have been slightly reduced, it was still a qualifying magistracy for entry to the Senate. Minimum age was 25 years.

Aedile: this position remained during the Empire, but it was not an essential part of the cursus honorum. However, as it served an important, elected, local role across the Empire’s domains, it provided the wealthy possessors of this position with an opportunity to gain publicity for their political careers and to accumulate voters. One of their roles was to stage expensive games for the people. And we know the Romans loved their games! The minimum age was 27.

Tribunus Laticlavius: this position was reserved for Patricians who served as the senior tribune in a Roman legion. These were not usually career soldiers, but rather would-be politicians on their way up the cursus honorum. The minimum age was 27 years.

Praetor: a praetorship was an important role during the Empire, and the duties of praetorswere actually increased as opposed to other positions. They were responsible for games and festivals, and propraetors (‘in place of praetors’) were chosen for military command as governors in some senatorial provinces. This was also one of the promagistracies during the Empire. A propraetorship extended the powers and time of one in that position. The minimum age was 30 years.

Praefectus: the role of prefect was an addition to the cursus honorum during the Empire. This was normally reserved for men of the Equestrian class, and served a variety of functions from being in charge of the grain supply (praefectus annonae) to the prefect of auxiliary forces in the army, or to the high position of Praetorian Prefect. Prefects gradually took over the roles of aediles. The minimum age was 30 years. However, the minimum age for the role of urban prefect was 32 years.

Legatus Legionis: there was great power to be had with the command of a legion, and the legionary legate was at the top of the chain of military command, beneath the emperor of course. Every legion across the empire had a commanding legate. The minimum age was 30 years.

Consul: during the Empire, the consuls lost all responsibility for military campaigns. It was more of an honorary position assigned (or assumed) by the emperors, and held for just two to four months. This meant that there could be up to twelve senators in this position in a given year. As an honourary position, the consuls were permitted to go around with a bodyguard of twelve lictors, and to wear a purple-bordered toga, a colour normally reserved for emperors. There were also proconsuls at this level. The minimum age was 32 years.

At this point, it is perhaps important to highlight the concepts of imperium and potestas. These were the types or classes of power held by some of the positions on the cursus honorum.

Imperium was supreme authority in matters of command in war, interpretation and execution of the law, as well as the passing of sentences of death as punishment. The positions that held imperium on the cursus honorum were consuls, praetors, the master of horse, and during the Republic, dictators. This was, perhaps, one of the great goals of the cursus honorum – to attain a position with imperium.

Potestas, on the other hand, was a general form of power held by all magistrates that allowed them to enforce the law according to the powers specific to their office.

There is no doubt that the cursus honorum could be a complicated route, especially with the changes, exceptions and dispensations over time between the Republic and the Empire. But, it remained an important tradition in Roman public life for the upper classes.

This was further complicated by the creation and inclusion of another class in Roman society – the Equestrian class.

In The Dragon: Genesis, one of the main characters seeking to climb the cursus honorum is of the equestrian class.

During the Republic, equestrians were below the senatorial class, but that changed over time and the two classes became more closely allied, so much so that the equestrians became the second level of the elite in Rome.

Emperor Augustus attempted to recast the equestrians as a military class, but this motion did not pass and, instead, around the year A.D. 69, equestrians became a sort of bureaucratic elite behind the senatorial governors of the provinces.

Because they posed less of a threat than the senatorial class, emperors like Commodus and Septimius Severus began to reward and rely more upon equestrians than ever before, even going so far as the grant them command of legions!

Equestrians were permitted to wear a narrow purple stripe on their togas, whereas men of the senatorial class wore a broad stripe.

For equestrians, the cursus honorum was a combination of military and administrative posts.

There were three commands for an equestrian officer in the military: a prefect of auxiliary infantry, a tribunus angusticlavius (on the cursus honorum), and a prefect of an auxiliary cavalry ala. The latter was one of the most prestigious positions available to equestrians. Equestrians could also become admiral of the navy, or a commander or prefect of the vigiles, Rome’s police and fire-fighting force.

As far as administrative positions for equestrians on the cursus honorum, they could be procurators in the provinces (such as a chief financial officer), or a prefect such as one in charge of the all-important grain supply.

As mentioned, perhaps the highest rank that could be granted to an equestrian during the Empire was one of the two positions of Prefect of the Praetorian Guard.

Whereas in the past, especially during the Republic, the path along the cursus honorum was clear, the later path for equestrians was not as stringent.

Though military service was expected, it came to be less of a requirement for equestrians and others.

Many did in fact seek to be career military officers without climbing the cursus honorum. The main character is The Dragon: Genesis is such a person.

However, those men with recognizable skills could receive special dispensation from military service, granted by the emperor, so that they could work in the law courts or imperial government. Emperor Hadrian did this, as did subsequent rulers.

Christopher Plummer as the Emperor Commodus flanked by lictors and the Praetorian Prefect (Fall of the Roman Empire – 1964)

The Roman Empire was vast, and there were any number of public positions up for grabs. Times changed, as did the requirements for public office. But Romans loved their traditions, and though the magistracies of the Republic were diminished in power over time, the cursus honorum was a path that was still respected and sought after.

The course of honours could be complex, and perhaps perilous, but then again, that it seemed to have been life in the world of Roman politics.

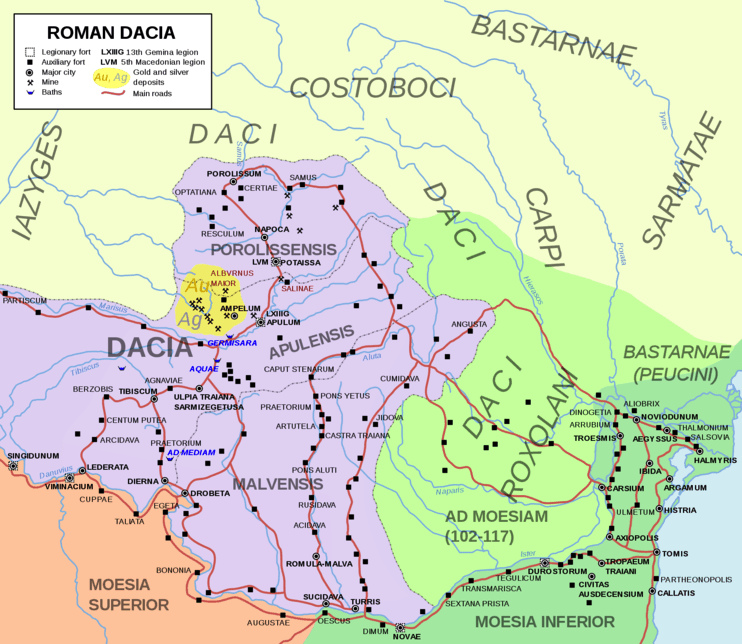

Part III – The Three Dacias

In Part III we are heading to what was once one of the most violent frontiers in the Roman Empire where, in the early second century A.D., one of the most famous of Rome’s military campaigns was waged. We’re heading into Dacia.

This is not, however, an in-depth study of the Roman campaign to conquer Dacia, but rather of the later division of the province, a move that heralded the importance of this province, and its resources, to Rome.

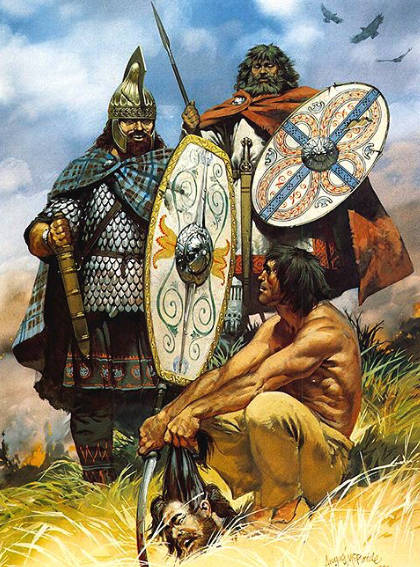

The ancient kingdom of Dacia, even now, conjures images of dark, mountainous forests where fearless warriors dwelled and worshiped strange gods. Today, the ancient lands of the Dacians comprise the region of modern Romania that strikes fear into the hearts of many: Transylvania.

But when the Romans waged war in Dacia, they were not fighting vampires or werewolves (read The Carpathian Interlude for that!). They were fighting a hearty race of warriors who would not be cowed by Rome’s might, and for years, the eyes of the Empire were set upon this area of Rome’s northern frontier.

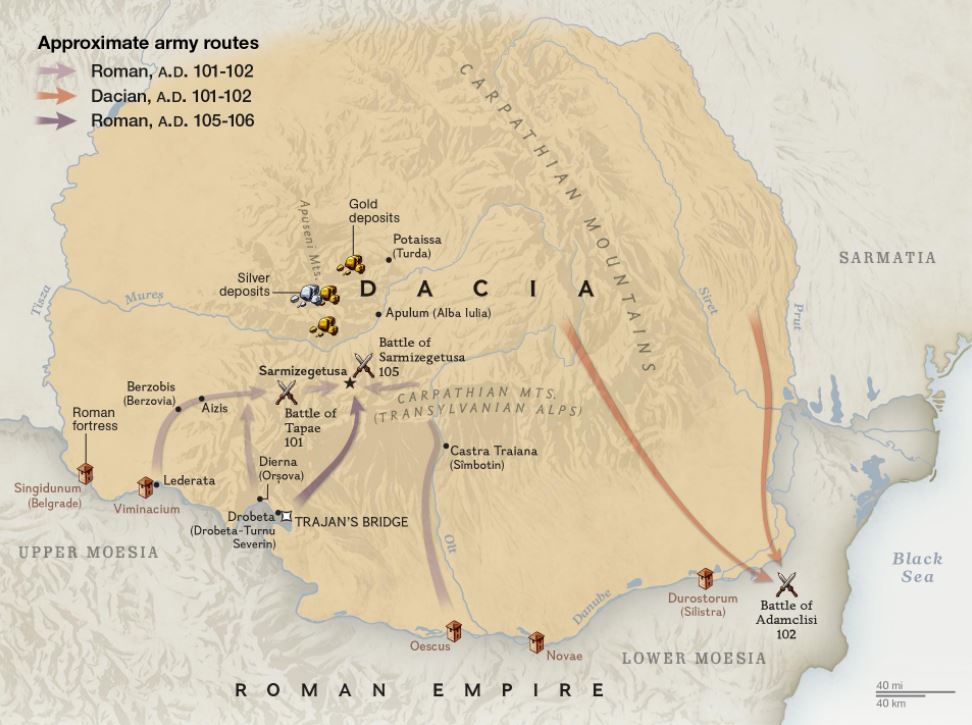

Rome and Dacian had been at odds for decades before the Emperor Trajan and his legions marched across the Danube.

Truly, Dacian aggression had received a boost since the defeat of a Roman army at the battle of Histria (c. 62 B.C.), during the Mithridatic Wars, under the great Dacian King, Burebista. Many years later, there was a resurgence in Dacian pride under King Duras who, in A.D. 85 attacked the Roman province of Moesia. Rome was defeated again by the Dacians at the battle of Tapae in A.D. 88. After this, Rome strengthened the front, but it was widely suspected that Dacia would have to be dealt with.

Enter emperor Trajan. He is perhaps the reason we are so familiar with the name of Dacia.

Emperor Trajan invaded Dacia in two big campaigns in A.D. 101-102 and A.D. 105-106, not only to end Dacian aggression, but also to annex a new province for Rome that was extremely rich in resources.

After spending some time in Rome he [Trajan] made a campaign against the Dacians; for he took into account their past deeds and was grieved at the amount of money they were receiving annually, and he also observed that their power and their pride were increasing. Decebalus, learning of his advance, became frightened, since he well knew that on the former occasion it was not the Romans that he had conquered, but Domitian, whereas now he would be fighting against both Romans and Trajan, the emperor. (Cassius Dio; Roman History, Book LXVIII)

Trajan crossed the Danube into Dacia with 50,000 troops in A.D. 101. After the second battle of Tapae, in which the Dacian king, Decebalus, was defeated, the Romans pressed on toward the Dacian capital of Sarmizegethusa. The Dacian king was no fool, however, and he sought terms so that he could fight another day.

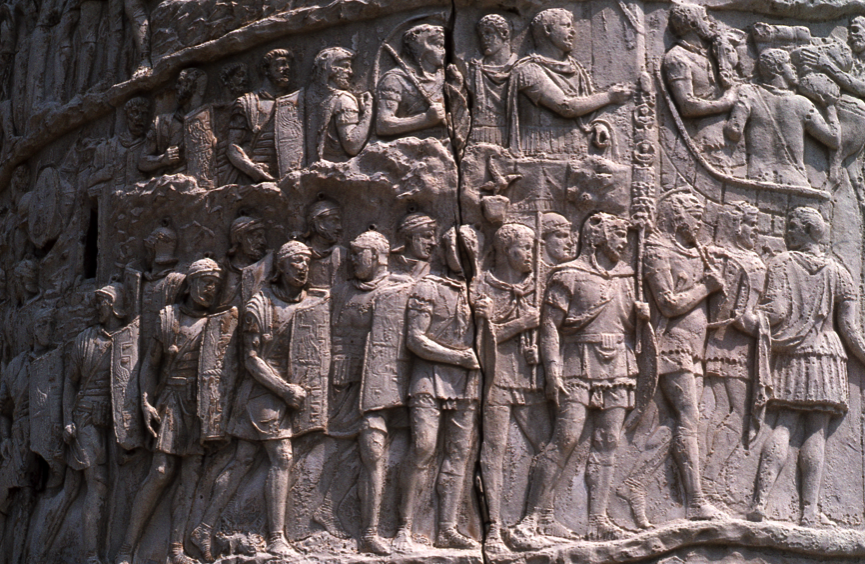

That day came in A.D. 105 when the Dacians attacked Roman outposts. This time, Emperor Trajan marched into Dacia and destroyed Sarmizegethusa. Decebalus committed suicide. The campaign is portrayed on the famous monument we now know as Trajan’s Column.

Despite some resistance under the Dacian king, Bicilis, Dacia became a new Roman province.

Trajan, having crossed the Ister by means of the bridge, conducted the war with safe prudence rather than with haste, and eventually, after a hard struggle, vanquished the Dacians. In the course of the campaign he himself performed many deeds of good generalship and bravery, and his troops ran many risks and displayed great prowess on his behalf. It was here that a certain horseman, after being carried, badly wounded, from the battle in the hope that he could be healed, when he found that he could not recover, rushed from his tent (for his injury had not yet reached his heart) and, taking his place once more in the line, perished after displaying great feats of valour. Decebalus, when his capital and all his territory had been occupied and he was himself in danger of being captured, committed suicide; and his head was brought to Rome. In this way Dacia became subject to the Romans, and Trajan founded cities there. The treasures of Decebalus were also discovered… (Cassius Dio; Roman History, Book LXVIII)

In conquering Dacia, Rome managed to add a resource-rich province to the empire. It was an extremely fertile land, perfect for agriculture, especially grain, which Rome always needed more of. The lands were ideally suited for livestock breeding, and the mountains yielded something which most civilizations hunger for: gold.

Over the years, Rome invested in massive mining operations in the province of Dacia and that, coupled with the other industries, meant that peace in Dacia would be highly profitable. Massive building projects were undertaken over the years with roads connecting military camps and ten cities, eight of which were coloniae where veteran troops were settled to begin new lives and families as part of the massive colonization project.

Dacia was developed into a new, urban province, and Rome was eager to protect this investment with a permanent garrison of about 35,000 troops which included two legions and up to forty auxiliary units.

At first, Rome had two administrative centres in Dacia. The first was Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegethusa, located just forty kilometres from the former Dacian capital of Sarmizegethusa Regia. This was the seat of the imperial procurator, Rome’s head finance officer in the province. The second main city at the time was Apulum. This was the seat of the military governor in Dacia, the greatest city in the province, and one of the largest along the entire Danube frontier. The XIII Gemina Legion was based there (the same legion that crossed the Rubicon with Caesar long before) within the walls of a fortress that covered 93 acres (37.5 hectares).

There was peace in Dacia after the conquest, but it was not without threat. Around the fringes of Rome’s new province, in the eastern Carpathian mountains and elsewhere, the ‘Free Dacians’, those tribes not under Rome’s direct control, posed a constant threat. That threat merited the massive garrison that was present in Roman-controlled Dacia. In the years to come, the Free Dacians would ally themselves with the powerful Sarmatians who would later put up a strong resistance to the later emperor, Marcus Aurelius.

During the reign of Emperor Hadrian (A.D. 117-138), Rome almost withdrew from Dacia because of problems with the Free Dacians, but also the issues that arose from administering the province. Changes were needed, and rather than pulling out of Dacia, Hadrian decided to make some adjustments.

Dacia was to be divided into two, with a second province of Dacia Porolissensis being created in western Transylvania. The high officials now included an imperial legate with consular powers, two legionary legates in charge of the two permanent legions, and the imperial procurator in change of finance.

In the novel, The Dragon: Genesis, however, the time period we are most concerned with is the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius (A.D. 138-161). Hadrian’s adjustments made a difference but it became clear that more was needed in Dacia, and Antoninus Pius took advantage of the period of peace in Dacia to take action.

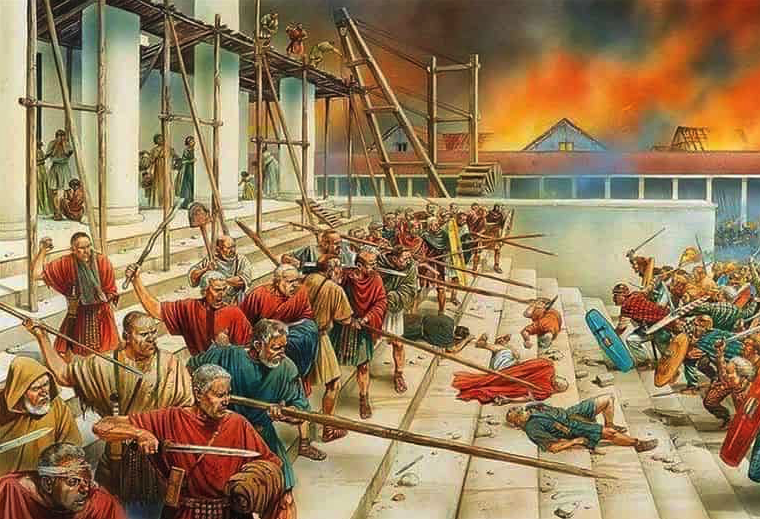

Massive repairs were made to the infrastructure of Dacia. All roads were repaired, fortresses were reinforced and updated to be more permanent, and the structures of the coloniae and other urban settlements were repaired. One such site was the great amphitheatre of Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegethusa.

In A.D. 158, the Dacians revolted, and this event brought about more change in the province. This brought about the creation of what has become known as the ‘Three Dacias’.

The emperor decided to add two more regions to the already existing Dacia Porolissensis by creating Dacia Apulensis, and Dacia Malvensis. Each zone was governed by an equestrian procurator, each of whom was responsible to the senatorial governor of the province.

The administrative capital of Dacia Porolissensis was Porolissum. This had been a military camp established by Trajan during the second invasion in A.D. 106. The purpose of this settlement was to defend the main route through the Carpathian Mountains. Five thousand auxiliaries were stationed there, and there were temples built to Jupiter, Nemesis, and Liber Pater.

The capital of Dacia Apulensis was Apulum, modern Alba Iulia. This is the setting for part of the novel, The Dragon: Genesis.

Apulum was the largest city in Roman Dacia and was the base of the XIII Gemina legion. It was also the seat of the military governor, which was not a coincidence, as the profitable goldmines of Dacia were located just to the west of Apulum and its legion.

The third of the new Dacias was Dacia Malvensis, the capital of which was Romula (also known as Malva) in the south. This settlement was a municipium at first, but later it became an official colonia under Septimius Severus (A.D. 193-211).

Romula had two forts and was the base for men from the VII Claudia, XXII Primigenia, as well as detachments of Syrian archers.

Peace however, even during the reign of Antoninus Pius, was fleeting.

In A.D. 161, upon the death of Antoninus Pius, there was trouble in Dacia once more.

The alliance between the Free Dacians and their Sarmatian allies came to fruition during the reign of Marcus Aurelius.

The three Dacias were merged once again, and the mega province of Tres Daciae was created. The capital was moved to Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegethusa, and two full legions were on the alert – the XIII Gemina at Apulum, and the V Macedonica at Potaissa.

War had returned to Dacia and, unlike the long period of Pax Romana enjoyed by Antoninus Pius, it would occupy Marcus Aurelius in the region for most of his reign.

Much attention was given to Dacia over the years, especially to its administration. It was obvious that the province was of great importance to Rome, not only strategically, but more so economically.

There was, however, further conflict there through the reign of Emperor Commodus (sole emperor from A.D. 180-192).

During the reign of Septimius Severus, the Pax Romana was restored in Dacia and the frontiers strengthened. Severus’ laws allowing soldiers to marry helped them to integrate and form family bonds across the Empire, including in Dacia.

There is no doubt that the history of Rome’s presence in Dacia was long and varied, but there can be no doubt that Rome left its mark in that land, and it is a mark that can still be seen and felt to this day.

Part IV – The Evocati

In Part IV, we’re going to be taking a brief look at a class of soldiers among the veterans of ancient Rome and how they often provided a strong back-bone in the ranks of Rome’s legions. We’re going to be looking at the Evocati.

In truth, primary and secondary sources do not have a great deal to say about the Evocati of ancient Rome. And yet, they were important, highly-respected members of society across the Empire.

So, what exactly was an evocatus?

The basic definition is that an evocatus was a retired Roman soldier who returned to duty after his completed term of service.

Some of you might remember this scene from the HBO hit series, ROME, in which Lucius Vorenus decides to go back into the service as an evocatus:

HBO’s ROME was a great series, but this scene seems more akin to the vigil kept by a newly-made knight during the Middle Ages. Truthfully, we don’t know how much, if any, ceremony was involved around becoming an evocatus. It may have been more of a clerical process, though religion was a big part of daily life.

What the scene above does, however, is portray the weight of the decision that re-enlisting might have had for a Roman who had already served for years in the legions.

From what we can gather, the Evocati gained more importance and respect during the Empire versus the Republic.

During the Roman Republic, the Evocati were ‘called-out’, which is where the meaning of the word comes from. This implies that they were compelled to return to service rather than given the choice. Calling out the Evocati might have been akin to instituting a draft in the Roman world.

During the Empire, however, veteran soldiers were invited to continue service as evocati, or they re-enlisted willingly.

There were two classes of evocati– the regular evocati of the legions, and the Evocati Augusti, the ‘Emperor’s Evocati’, who were former Praetorians who became evocati.

Before we go further, we should take a brief look at the veterans of ancient Rome.

Firstly, how long a man served depended on which military force he was a part of. The lengths of time shift slight back and forth over the centuries, but generally, a legionary soldier served for 20 years, a Praetorian guardsman served or 16 years, and an auxiliary trooper served for about 26 years.

These terms of service might seem short to us today, especially when some people spend up to 35 years in a career, but it is important to keep in mind that the average age of mortality in the ancient world was much younger than today.

Twenty years spent in the legions was a much greater portion of a man’s life than we might think.

For veterans, the type of discharge one received was important, as it also determined the type life one might have enjoyed afterward. The discharge types were missio causaria (discharge through injury or illness), missio ignominiosa (dishonourable discharge), and honesta missio (honourable discharge).

If one completed the full term of service, and received an honourable discharge, then life was often pretty good. Veterans had legal status in ancient Rome, and were protected by laws granting them certain rights and immunities. They could go on to be local decurions (a sort of city councilor), and they could form collegia.

Veterans received land grants too, and it is said that Emperor Augustus settled about 300,000 veterans in colonies across the empire.

Upon being honourably discharged, veterans also received money, in addition to land. A legionary received 3000 denarii (later raised to 5000), and a Praetorian received 5000 denarii (later raised to 8250). Soldiers were also given back the savings they had been forced to put away during their time in the army. Under Hadrian, the land grants to veterans stopped, but they were still given fair financial recompense.

It seems that world leaders today could take their cue from the ancient Romans when it comes to taking care of veterans after their service is finished.

Veterans were leaders in coloniae across the Empire, and there was a peace and security present where veterans settled. This in turn attracted other civilians as the veterans also provided a skilled workforce locally. They were good for the economy too.

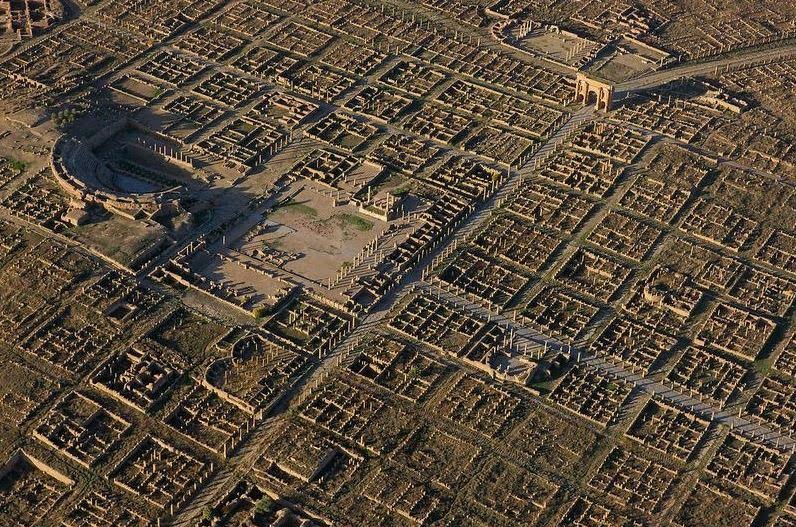

One example of a thriving veteran colonia on the edge of the Empire is Thamugadi, in Numidia, which was located a short distance from the legionary fortress of Lambaesis.

Aerial view of the colonia of Thamugadi, Numidia (North Africa), where veterans of the III Augustan Legion at Lambaesis were settled.

Not everyone was happy, however, with the presence of Roman veterans. Tacitus tells us of the tension between local Britons and their retired Roman conquerors:

And the humiliated Iceni feared still worse, now that they had been reduced to provincial status. So they rebelled. With them rose the Trinovantes and others. Servitude had not broken them, and they had secretly plotted together to become free again. They particularly hated the Roman ex-soldiers who had recently established a settlement at Camulodunum. The settlers drove the Trinovantes from their homes and land, and called them prisoners and slaves. The troops encouraged the settlers’ outrages, since their own way of behaving was the same – and they looked forward to similar license for themselves. (Tacitus, Annals XIV.33)

If most veterans who had been honourably discharged seemed to enjoy a good life (for them as Romans, that is), doing as they pleased on their granted lands, why might they have considered joining the ranks of the Evocati and going back to war?

Why were the Evocati even needed with so vast an empire?

Well, the Evocati were a sort of ready, trained militia that could be called upon in times of emergency, such as during the Boudiccan revolt of A.D. 60 when Governor Paulinus Suetonius called upon 2500 evocati to join the fighting. As Tacitus tell us, “the old battle-experienced soldiers longed to hurl their javelins. So Suetonius confidently gave the signal for battle.”

Evocati reported directly to the governor of a Roman province, so, in times of emergency, they could be used to reinforce the garrison.

Other reasons men might join the Evocati were the need for money if they had fallen on hard times, or even the need for purpose in life after the army. Just as today, it may not have been easy for a career soldier to reintegrate into civilian society, and so many might have welcomed the opportunity to go back to the ranks.

Lastly, men could be requested to re-enter service by the consul or their former commander. This happened frequently during civil wars. At the battle of Pharsalus, Pompey used 2000 evocati against Caesar, and later, Octavian enlisted 3000 evocati when going up against Marcus Antonius. In A.D. 67, Mucianus, the governor of Syria, is said to have enlisted 13,000 evocati to move against Emperor Vitellius.

I cannot give the exact strength…for the Evocati. Augustus was the first to employ this corps when he re-enlisted those troops who had served under Julius Caesar to fight against Antony, and he kept them in service afterward. To this day, they constitute a special corps and carry ceremonial rods as centurions do.(Cassius Dio, The Roman History 24)

When Augustus made the Evocati a sort of official class, as hinted at by Cassius Dio, was it just so that they could fight in times of emergency, or did they have some other purpose? What incentives were there for a veteran who had already served for years in the army to return to service?

It seems that when a man became an evocatus, he had special privileges. The Evocati did not go back to digging ditches and manning the front lines in battle. They were too valuable an asset for that.

Apart from fighting when the need arose, the Evocati fulfilled various other roles. They became instructors of aquilifers and other standard bearers, and physical trainers for the regular troops. Many evocati returned to the ranks to be officers or qualified and skilled administrators in the legions. Some joined the vigiles, Rome’s police and firefighting force. Others were army surveyors, architects, and quarter masters.

There were many roles an evocatus could fill in the legions.

More often, the higher-ranking and skilled evocati came from the Praetorian Guard, though sometimes from the regular legions. It could be a plum job.

Rome had a massive military force when you consider the regular legions, Praetorian Guard, and numerous auxiliary forces across the Empire. It has been estimated that about 250 men left each legion every year, and that about 15,000 soldiers retired from the Roman military annually.

That’s a huge number of trained troops to loose on a regular basis!

But Rome took care of it’s veterans for the most part. Men were rewarded accordingly for their years of service with money and lands. They could become valued and respected members of society, leaders in their own right. And even after their term as evocati, these veterans maintained that respect.

The Evocati of ancient Rome were, it seems, not only a skilled fighting force that could be called upon in times of need, but they were also a respected and important class in Roman society.

It may not have been a lavish lifestyle, but it does seem that life as an evocatus might have been better than most.

Part V – The Two Emperors of Rome

The Dragon: Genesis spans the reigns of a few emperors. It begins during the reign of Antoninus Pius, but then moves on into unique period for Rome, a time when it was ruled jointly by two emperors, Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.

Surprisingly, as we shall see, these two men ruled amicably, despite their differences. However, the peace of Antoninus’ reign was over, and the new emperors faced pressures and threats from outside.

First, we need to set the stage.

By the time Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus came to the imperial throne, the Roman Empire had enjoyed a period of unprecedented peace under the well-loved emperor, Antoninus Pius, who had reigned for the longest period of time since Augustus, from A.D. 138-161.

One of the only sources that survives for this period in Rome’s history is the Historia Augusta, a highly-contested, often doubted, source that relates some of the details of the reigns of certain of Rome’s emperors.

During Antoninus’ reign, a young Marcus Aurelius was already making himself known in the upper echelons of Roman society, so much so that he was a favourite of Emperor Hadrian before Antoninus Pius donned the purple.

It is believed that Emperor Hadrian would have liked for Marcus Aurelius to succeed him, but because of his young age, he chose Antoninus Pius. Prior to his death in A.D. 138, Hadrian, who cared much for the young Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, seems to have pressured Antoninus Pius into adopting them, thus ensuring their possible involvement in a later succession. Hadrian seems to have been a forward-thinking man.

Antoninus Pius, of course, agreed.

Marcus did not seem suitable, being at the time but eighteen years of age; and Hadrian chose for adoption Antoninus Pius, the uncle-in‑law of Marcus, with the provision that Pius should in turn adopt Marcus and that Marcus should adopt Lucius Commodus. And it was on the day that Verus was adopted that he dreamed that he had shoulders of ivory, and when he asked if they were capable of bearing a burden, he found them much stronger than before. When he discovered, moreover, that Antoninus had adopted him, he was appalled rather than overjoyed, and when told to move to the private home of Hadrian, reluctantly departed from his mother’s villa. And when the members of his household asked him why he was sorry to receive royal adoption, he enumerated to them the evil things that sovereignty involved.

(Historia Augusta, The Life of Marcus Aurelius 5)

Then, in A.D. 140, Marcus Aurelius was made consul with Antoninus and given the title of ‘Caesar’ which officially made him Antoninus’ heir.

Now, Antoninus, who was married to Hadrian’s niece, Faustina (the Elder), did have four children, two sons and two daughters, but they all died young, except for his daughter Faustina (the Younger).

In A.D. 146, Marcus Aurelius was married to Faustina the Younger, further cementing his role as Antoninus’ successor, a role he is said not to have wanted.

As time passed, Antoninus Pius grew older and weaker, and Marcus Aurelius took on more administrative duties for the empire, especially after the death of Antoninus’ trusted Praetorian Prefect, Gavius Maximus.

Then, in A.D. 161, while at an estate in Etruria, Antoninus grew ill and called the imperial council together to formally pass the state to Marcus Aurelius. It is said that one of the last words he uttered when a tribune came to him for the night’s watchword was aequanimitas, or equanimity.

One has to wonder if Antoninus Pius really did feel a true sense of calm as he faced death, knowing that he had ruled well and that he was leaving the Empire in capable hands.

The reign of Marcus Aurelius was underway.

But Marcus Aurelius did not want to rule, and so the wheels were set in motion for the reign of two emperors and friends.

However, before we go further, let us look at these two men. Who were Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus?

Marcus Aurelius was born Marcus Annius Verus, and studies played a large role in the young man’s life. His teachers included Diognetus and Tuticius Proclus who seems to have introduced him to philosophy, a subject that Marcus took to immediately.

Philosophy played a large role in the life of Marcus Aurelius, affecting his life and his character. Even in A.D. 140 when he was made Emperor Antoninus’ heir, Marcus began studying with the sophist, Herodes Atticus, the man who built many monuments in Greece, including the great theatre beside the Acropolis of Athens. He also studied with Marcus Cornelius Fronto.

But it was the philosopher Quintus Junius Rusticus who is said to have introduced Marcus to the ways of stoicism that he would come to love and adhere to. Marcus Aurelius’ work, Meditations, was the product of his stoic view of the world and it is still widely read to this day.

One could say that stoicism is what got Marcus Aurelius through the more difficult times of his reign.

As far as a home life, Marcus Aurelius had thirteen children with his wife/cousin, Faustina the Younger, and among these were Lucilla and Commodus.

It seems that Hadrian’s favour of Marcus, and the condition he might have placed on Antoninus to adopt Marcus in order to succeed, weighed heavily on the young philosopher. Marcus was Antoninus’ sole heir, but when Antoninus died in A.D. 161, and the Senate made Marcus ‘Augustus’, ‘Imperator’, and ‘Pontifex Maximus’, it is said that he resisted. He preferred the philosophic life, but his stoicism compelled him to accept his duty, and despite his reluctance, he rose to the challenge:

Toward the people he acted just as one acts in a free state. He was at all times exceedingly reasonable both in restraining men from evil and in urging them to good, generous in rewarding and quick to forgive, thus making bad men good, and good men very good, and he even bore with unruffled temper the insolence of not a few.

(Historia Augusta, The Life of Marcus Aurelius 12)

The Senate was going to confirm him as sole emperor, but Marcus refused unless Lucius Verus, his ‘brother’ beneath Antonius Pius, was given equal powers.

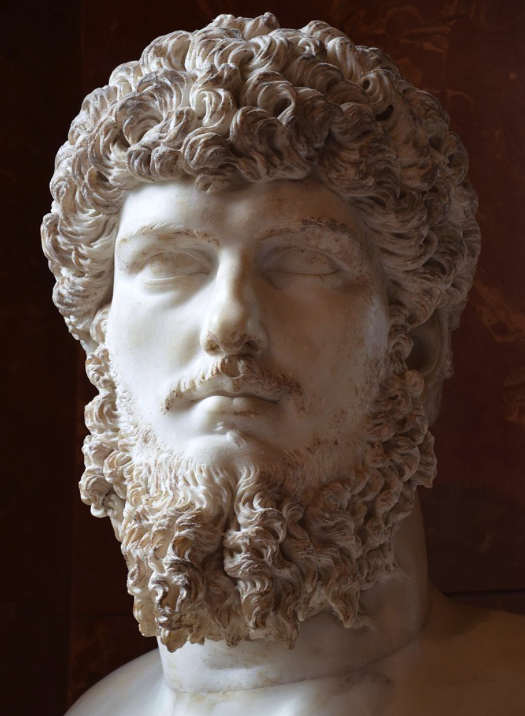

The Senate approved, and though officially, Marcus had more authority, Rome had two emperors for the very first time in its history: Imperator Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus, and Imperator Lucius Aurelius Verus Augustus.

What do we know about Lucius Verus?

Apart from what the Historia Augusta tells us, we know relatively little about Marcus Aurelius’ co-ruler.

Born Lucius Ceionius Commodus (the Younger), he was a member of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty, and his father, Lucius Aelius Caesar was Emperor Hadrian’s fist adopted son and heir. However, Verus’ father died in A.D. 138, and that is when Hadrian decided on Antoninus Pius as his successor.

Lucius Verus and Marcus Aurelius, though friends and ‘brothers’, appear to have been quite different.

Whereas Marcus Aurelius remains the calm stoic, preferring philosophy and a quieter life, Lucius Verus’ interests were said to be lower. He was fanatical about the games and chariot races, as well as gladiatorial combat, and he was said to enjoy lavish parties. He was quite the opposite of Marcus.

Lucius Ceionius Aelius Commodus Verus Antoninus — called Aelius by the wish of Hadrian, Verus and Antoninus because of his relationship to Antoninus — is not to be classed with either the good or the bad emperors. For, in the first place, it is agreed that if he did not bristle with vices, no more did he abound in virtues; and, in the second place, he enjoyed, not unrestricted power, but a sovereignty on like terms and equal dignity with Marcus, from whom he differed, however, as far as morals went, both in the laxity of his principles and the excessive licence of his life. For in character he was utterly ingenuous and unable to conceal a thing.

(Historia Augusta, The Life of Lucius Verus 1)

Despite their differences, the two emperors seemed to have been able to make things work. It was as if they balanced each other. Marcus Aurelius is said to have disapproved of his co-ruler’s behaviour and vices, but he also saw that Lucius Verus fulfilled his imperial duties. Marcus even went so far as to betroth his eleven year old daughter, Lucilla, to Lucius Verus.

Things were looking bright in Rome. The emperors enjoyed the love of the people, and yet, there was great respect for the Senate and its traditions. Free speech was permitted, and the public service in government was running smoothly.

The reign of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, however, was not to be the period of Pax Romana that marked the golden age of Antonius Pius.

Sadly, the drums of war began to sound across the Empire.

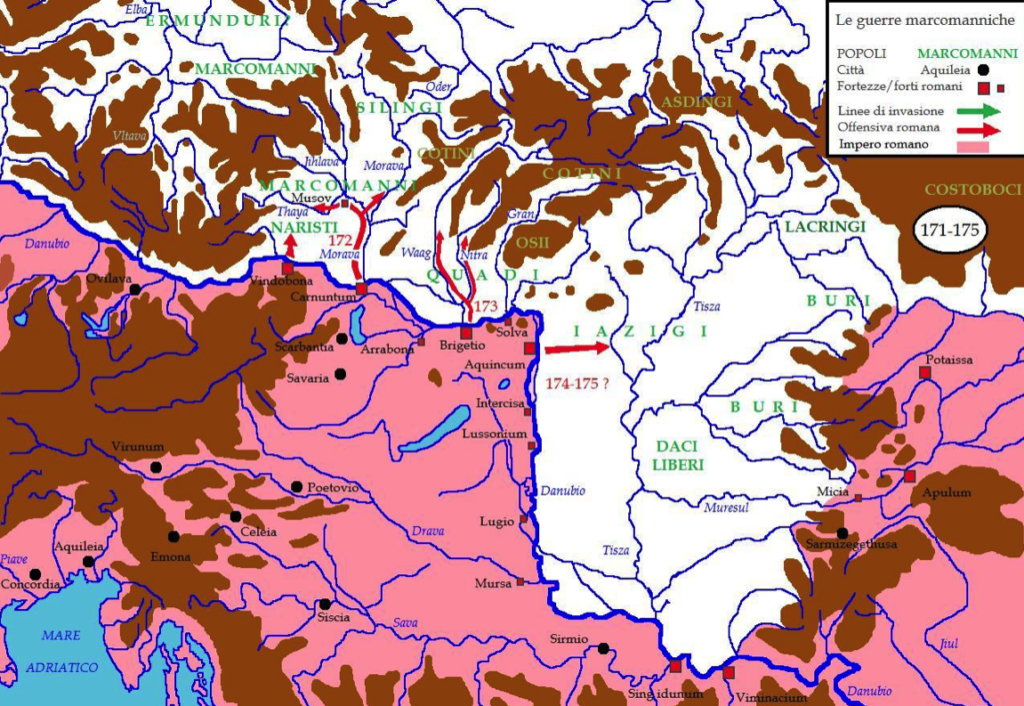

Two major wars marked the period: the Parthian war (A.D. 161 – 166) in the East, and the Marcomannic Wars (A.D. 166 – 180) in the North.

Because of aggressions shown by Vologasses IV of Parthia, and the subsequent massacre of one legion led by Marcus Severianus, the governor of Cappadocia, it was decided that Rome’s legions needed to march east.

The campaign was led by Lucius Verus, while Marcus Aurelius remained in Rome.

In fact, Verus spent most of his rule in Antioch, overseeing the Parthian campaign which was, in many ways, a success. Order was eventually restored.

It is said that Verus was a responsible commander and that he brought back discipline to the ranks of the Syrian legions who had grown soft during the prior peace. He was a good commander who knew when and how to delegate to men who were more knowledgeable, including his generals Marcus Claudius Fronto, and Martius Verus.

However, his vices followed him there, and in Antioch he is said to have lived a life of extreme luxury with grand parties. And he kept himself updated on the chariot racing in Rome by ordering regular reports sent to him about his favourite teams.

He also spend a great deal of time in the East with his mistress, Panthea, a low-born woman who was said to be a great beauty. Still, despite this, he did travel to Ephesus c. A.D. 163 to marry Marcus Aurelius’ daughter, Lucilla, who was only about fourteen at the time. She became Lucilla Augusta and they had three children together, all of whom died young. After the marriage, Verus returned to Antioch.

Lucius Verus certainly preferred bread and circuses to Marcus Aurelius’ love of learning and philosophy, but still, they seem to have worked well together.

When the Parthian campaign was successfully concluded, Lucius Verus was given the title of Parthicus Maximus. He and his men returned to Rome, but they were not only carrying coronae of victory with them. They also brought plague.

We will cover the ‘Antonine Plague’, as it is known, in the next post in this blog series, but suffice it to say, it was devastating.

And as Rome fought the plague at home, the Germanic tribes took the opportunity to attack in the North.

The Marcomannic Wars raged from A.D. 166 – 180 in a series of three major campaigns that took Rome’s legions across the Danube frontier against the rebellious tribes which included the Quadi, Marcomanni, Iazyges, Sarmatians, and the Dacians who had been peaceful for a time during the reign of Antoninus. It was an all-out offensive by the barbarian tribes.

This time, both Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus marched north with the legions to wage a war that would last the rest of their lives.

After two years of campaigning, the two emperors returned to Rome and it was then that Lucius Verus fell ill. Some said that it was food poisoning that killed him, but modern historians believe that it may well have been the plague that had returned with his men from Parthia.

Lucius Verus died and was grieved by Marcus Aurelius who, fittingly, put on games in his honour. He also had his co-emperor deified by the Senate as ‘Divus Verus’.

Marcus Aurelius now ruled alone.

After the death of Verus, Marcus Antoninus held the empire alone, a nobler man by far and more abounding in virtues, especially as he was no longer hampered by Verus’ faults, neither by those of excessive candour and hot-headed plain speaking, from which Verus suffered through natural folly, nor by those others which had particularly irked Marcus Antoninus even from his earliest years, the principles and habits of a depraved mind. Such was Marcus’ own repose of spirit that neither in grief nor in joy did he ever change countenance, being wholly given over to the Stoic philosophy, which he had not only learned from all the best masters, but also acquired for himself from every source.

(Historia Augusta, The Life of Marcus Aurelius 16)

Marcus Aurelius has come down to us as one of the most noble emperors of Rome, the last of the ‘five good emperors’ as they have come to be known.

After the death of his friend and co-emperor, Marcus Aurelius brought the Marcomannic Wars to a successful conclusion. He also improved the judicial system as well as the system for distributing food. The management of the treasury was made more efficient too. He saw to the care of children, and constantly improved the civil service of which he had been a part in his early career. The Senate too, remained respected.

If he made one mistake during his reign, it was perhaps to trust his own son.

After the death of Lucius Verus and a period of lone rule, Marcus Aurelius named his son, Commodus, as co-ruler in A.D. 177. We will not go into the details of Commodus’ rule here. We need only know that it was nothing like his father’s reign, or Antoninus Pius’ before him.

Being the ruler of the greatest empire in the world could not have been an easy burden, especially for a man like Marcus Aurelius who had duty thrust upon him. This was in contrast to the life of thinking which he obviously preferred. In many ways, perhaps many of us can relate today. How many people live lives they had not intended for themselves?

Marcus Aurelius’ stoic philosophy no doubt helped him to come to terms with what fate had dealt him, but perhaps his insistence to the Senate that Lucius Verus rule with him was his way of alleviating some of the burden he felt?

It is difficult to say, but one thing we can be certain of is that, despite the lack of sources, the reign of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus will always stand out in the history of Rome as a time like no other.

Part VI – The Antonine Plague

In Part VI, we’re going to be looking at one of the most brutal enemies Rome has ever had to face, an enemy that slipped past the frontiers and penetrated the heart of Rome itself.

We’re not talking about barbarian tribes north of the Danube frontier, or waves of Parthian cataphracts from the East. No, the most deadly enemy Rome had to contend with during the reign of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus was the plague.

And it almost completely destroyed the Roman Empire.

The ‘Antonine Plague’, as it is now known, began in A.D. 165 and lasted into the early 180s. It was the largest pandemic Rome had ever had to deal with to that point in its history.

This was an enemy that did not discriminate when it came to victims.

…after the victory over the Parthians, there occurred so destructive a pestilence, that at Rome, and throughout Italy and the provinces, the greater part of the inhabitants, and almost all the troops, sunk under the disease.

(Eutropius, Roman History, Book VIII)

Before we get into the few specifics of the Antonine Plague, we should first take a look at how Romans viewed disease, and what could have started a pandemic of these proportions.

In the ancient world, Roman medical practices were a strange mixture of practical Greek methods and Roman religious beliefs.

Disease and plague were to be feared, and the gods who were associated with them were to be propitiated.

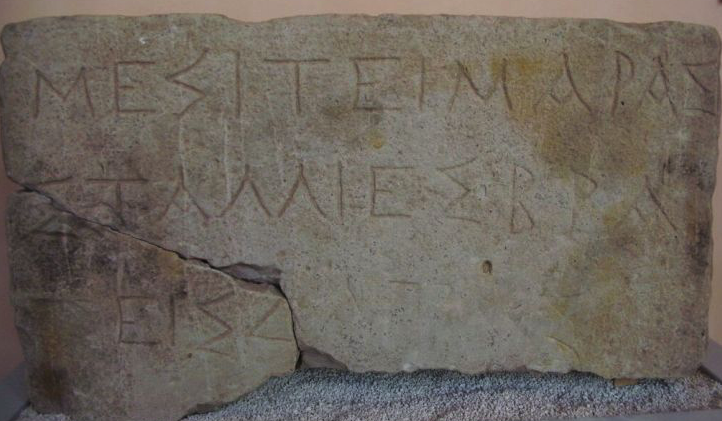

In the Roman world, it was believed that sulphurous fumes that came out of the earth could be responsible for epidemics and plagues. As a result, the Romans made offerings to the Mefitis, a goddess of sulphurous fumes and of plagues.

A cult of Mefitis began in the volcanic regions of central and southern Italy, and her main shrine was located in Samnite territory on the slopes of the volcano of Ampsanctus.

In Rome, there was a temple of Mefitis on the Esquiline hill, and at Cremona, in the North of Italy, there was a temple dedicated to the goddess of plagues just outside the city walls.

In addition to offerings to the Goddess of Plagues and Fumes, the Romans also held games in the hopes that these – also an aspect of religion – would help them to avoid disease and keep this deadly enemy from their doors.

The Ludi Saeculares, or Secular Games (also known as the Tarentine Games) were held once every century with the intention that they would help Rome avoid pestilence.

The fist Secular Games were held by the consul Publius Valerius Poplicola in 509 B.C. at the altar of Dis and Proserpina located on the Campus Martius at a spot known as ‘Tarentum’, hence the other name of ‘Tarentine Games’.

In addition to sport, the games also included three days and three nights of stage plays.

One has to wonder how it was decided when the Ludi Saeculares were to take place, and details are sketchy about this. But, we do know of two other instances in which the games were held.

In 17 B.C. the Emperor Augustus held the games which culminated in a ceremony at the temple of Apollo, on the Palatine hill, a temple Augustus built. Among other things, Apollo was a god of healing. (Those who have read Children of Apollo, will be familiar with this temple.)

The Ludi Saeculares were also held in A.D. 204 by none other than Septimius Severus who came out the winner in the civil war that followed the death of Commodus, Marcus Aurelius’ son and heir.

Severus’ games came in the wake of the Antonine Plague, so it is likely that after the devastation, it was believed the gods needed to be propitiated once more.

What might have been the causes of the spread of disease in ancient Rome?

There are several possibilities.

First of all, sewage and bad hygiene were a prime suspect.

When we think of ancient Rome, we tend to think of baths, running water, pristine white marble etcetera, but this is not entirely accurate. Despite the presence of running water and sewer systems, the truth was that many Romans did not have access to these things, especially in poorer neighbourhoods like the Suburra. In ancient Rome, most sewers were privately owned by the rich, and so, in the poor, tightly-packed neighbourhoods where tenement blocks rose up from the streets, often the only place to dump faeces, garbage and other waste was directly onto the street. With the preponderance of flies and dogs around all this filth, bacteria was everywhere.

Another reason why disease might have spread were the public baths.

This seems contrary to what one might expect, but despite the Roman propensity for bathing and cleanliness, the hot water used in the baths of Rome and elsewhere was not cleaned chemically like today (using chlorine). As a result, bacteria would have thrived in the public baths.

Diet could also play a role in the spread of disease, especially as many Romans were malnourished. The diet of the average Roman consisted mainly of grains, distributed by the state. They had some vegetables and fruit, but meat was actually uncommon, and when they did have meat, there were no food standards to ensure freshness and quality. And so, food was often contaminated with parasites, as was the drinking water of most people.

Disease spread easily in densely populated areas, and as one of the most populous cities in the world at the time, Rome was especially vulnerable. This was certainly true in poorer neighbourhoods where many people shared small spaces, making the transmittal of disease easier.

The Antonine Plague was said to be transmitted through touch.

Lastly, another reason for the possible spread of plague and disease was deforestation around Rome and especially along the banks of the River Tiber. The clearing of trees led to the creation of rising water and an increase in the size of the marshes near Rome where mosquitoes and other carriers of diseases, such as malaria, flourished.

Coastal lagoon along shores of Lake Fogliano in the Pontine Plain – breeding ground for mosquitoes and diseases like malaria (Wikimedia Commons)

Part of the The Dragon: Genesis takes place during the Antonine Plague which began in A.D. 165.

This particular disease, however, did not originate in the city of Rome.

From A.D. 161-166, Emperor Lucius Verus was waging war against the Parthians in the East. While they were in Seleucia, a sickness began to spread among the troops of his legions, a sickness that they brought back with them to Rome and other parts of the Empire.

It was his [Lucius Verus] fate to seem to bring a pestilence with him to whatever provinces he traversed on his return, and finally even to Rome. It is believed that this pestilence originated in Babylonia, where a pestilential vapour arose in a temple of Apollo from a golden casket which a soldier had accidentally cut open, and that it spread thence over Parthia and the whole world. Lucius Verus, however, is not to blame for this so much as Cassius, who stormed Seleucia in violation of an agreement, after it had received our soldiers as friends. This act, indeed, many excuse, and among them Quadratus, the historian of the Parthian war, who blames the Seleucians as the first to break the agreement.

(Historia Augusta, The Life of Lucius Verus, 8)

What little we know of the disease comes from the observations of the physician, Galen, who was called upon by Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus at the time, and who recorded some of his observations in scattered texts, including his Methodus Medendi.

From Galen’s descriptions, it is thought today that the Antonine Plague was an outbreak of small pox. The symptoms included severe fever, diarrhea, pharyngitis, and on the ninth day of the illness, the appearance of skin eruptions (boils or pustules).

And there was such a pestilence, besides, that the dead were removed in carts and wagons. About this time, also, the two emperors ratified certain very stringent laws on burial and tombs, in which they even forbade any one to build a tomb at his country-place, a law still in force. Thousands were carried off by the pestilence, including many nobles, for the most prominent of whom [the emperor] erected statues. Such, too, was his kindliness of heart that he had funeral ceremonies performed for the lower classes even at the public expense…

(Historia Augusta, Life of Marcus Aurelius, Part I, 13)

The Antonine Plague brought devastation to Rome and the Empire at large. Cassius Dio wrote that it caused up to 2000 deaths a day in Rome itself. It has been estimated that there were approximately 5 million deaths from this pandemic, and that about one third of the Empire’s population was wiped out.

One theory for the widespread destruction wrought by the Antonine Plague is that this was the very first time small pox appeared in the Empire, and so, without any sort of prior immunity, the people were as lambs to the slaughter.

It also massacred the army in which it had started, spreading to Gaul and along the entire Rhine and Danube frontier. Rome’s defences were down, and the tribes to the north chose this moment to attack.

It is hard to imagine the terror spreading across the Empire during this terrible time in which Rome was beset by the Marcomanni and their allies in the north and the plague at its heart.

Eventually, the barbarians were defeated – and that alone is a wonder! – but the plague, even though it eventually stopped, left the Roman Empire scarred. Entire towns were wiped out and outposts were lost because the troops were too sick to fight.

It has also been hypothesized that the Roman embassies that Marcus Aurelius had sent to China’s Han emperor were perhaps responsible for the outbreak of plague that was recorded there.

There can be little doubt that the Antonine Plague was perhaps the most deadly crisis Rome had ever been faced with. The plague did not discriminate, striking at rich and poor, weak and strong alike. It seems likely that it was also responsible for the death of Emperor Lucius Verus, who died two years into the northern wars, and maybe even Rome’s great philosopher emperor, Marcus Aurelius, who passed in A.D. 180 just before the end of the pandemic.

He died in the following manner: When he began to grow ill, he summoned his son and besought him first of all not to think lightly of what remained of the war, lest he seem a traitor to the state. And when his son replied that his first desire was good health, he allowed him to do as he wished, only asking him to wait a few days and not leave at once. Then, being eager to die, he refrained from eating or drinking, and so aggravated the disease. On the sixth day he summoned his friends, and with derision for all human affairs and scorn for death, said to them: “Why do you weep for me, instead of thinking about the pestilence and about death which is the common lot of us all?” And when they were about to retire he groaned and said: “If you now grant me leave to go, I bid you farewell and pass on before.” And when he was asked to whom he commended his son he replied: “To you, if he prove worthy, and to the immortal gods”. The army, when they learned of his sickness, lamented loudly, for they loved him singularly. On the seventh day he was weary and admitted only his son, and even him he at once sent away in fear that he would catch the disease. And when his son had gone, he covered his head as though he wished to sleep and during the night he breathed his last. It is said that he foresaw that after his death Commodus would turn out as he actually did, and expressed the wish that his son might die, lest, as he himself said, he should become another Nero, Caligula, or Domitian.

(Historia Augusta, Life of Marcus Aurelius, Part II, 28)

Part VII – Sibling Rivalry: The Plot to Kill Commodus

Commodus was guilty of many unseemly deeds, and killed a great many people.

(Cassius Dio, The Roman History)

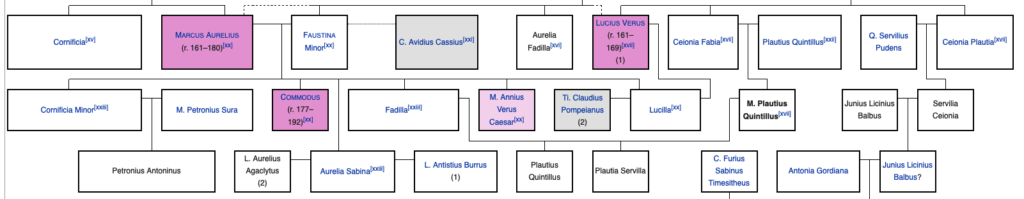

In this seventh and final part of the blog series, we’re going to be taking a brief look at the children of Marcus Aurelius and Faustina Minor (‘the younger’), the reign of Emperor Commodus, and the plots against his life.

Was Commodus really the monster we imagine him to be, the megalomaniacal ruler we were confronted with in the movie Gladiator?

Some people view the reigns of Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius as a sort of golden age of rulership in the Roman World. That was certainly true of Antoninus Pius, and perhaps less for Marcus Aurelius’ reign, but any sense of a golden age certainly ended with the accession of Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus who ruled as sole emperor from A.D. 180-192.

It was at this time that the Roman Empire perhaps took a turn for the worst. The time of the ‘five good emperors’ was at an end.

Because of popular culture, the two children of Marcus Aurelius and Faustina Minor that most people are aware of are Commodus and his sister, Annia Aurelia Galeria Lucilla, or ‘Lucilla’. However, what many may not know is that Marcus Aurelius and Faustina Minor had thirteen children together over the period of their thirty-year marriage.

Most of these young Aurelii died young. There was the first-born, Domitia Faustina, who died at the age of five in A.D. 151. Then there were Titus Aelius Antoninus and Titus Aelius Aurelius who both died in 149. After the birth of Lucilla in 150, two more children were born, Annia Galeria Aurelia Faustina, and Tiberius Aelius Antoninus who died in 151 and 155, respectively, before another unknown child died in 157. Titus Aurelius Fulvus Antoninus, Commodus’ twin brother, died at the age of four in 165, then Marcus Annius Verus Caesar passed at the age of seven in 169, followed by a young Hadrianus some time after that.

But there were other surviving siblings of Commodus and Lucilla who are not often mentioned in the history books, notably three more sisters: Annia Aurelia Fadilla (c. 159-211), Annia Cornificia Faustina Minor (160-212), and the youngest of Marcus Aurelius and Faustina Minor’s children, Vibia Aurelia Sabina (170-216).

Obviously, infant mortality rates were very high in the ancient world, even for the upper classes. But, in hindsight, when one looks at the number of children Marcus Aurelius and Faustina Minor had, despite their mortality rates, one has to wonder if the emperor was indeed obsessed with having an blood-heir to the throne, despite the fact that he and his illustrious predecessors came to the throne through adoption.

Before we look at the reign of Commodus, let us first look at the children of Marcus Aurelius who did survive to play a part in the drama that was to unfold after the death of their father in A.D. 180.

Annia Aurelia Galeria Lucilla (150-182) was the eldest daughter to survive her parents. She was born about eleven years before Commodus. As we know, she was betrothed and wed as a teenager to her father’s co-ruler, Lucius Verus. After Verus passed away from illness, perhaps from the plague his troops had brought back from the East, she was forced to marry Tiberius Claudius Pompeianus, a respected general of her father’s who was quite a bit older than her, having been born in A.D. 125.

Snapshot of family tree of Marcus Aurelius and Faustina Minor (Wikimedia Commons – Nerva/Antonine Dynasty)