Salvete, history lovers!

This week on the blog, I’m thrilled to invite archaeologist, Roman history re-enactor, and owner of Apicius Sauces Ltd., Rita Roberts, to share her story about her wonderful experiences with living history and how, through a bit of serendipity and creativity, she was able to launch a successful (and tasty!) enterprise with a little help from the famous gastronome of ancient Rome, Apicius.

Get ready for a fascinating look at the life of a Roman re-enactor. Be sure to read all the way to the end for an amazing recipe!

Take it away, Rita!

Living History

While working as an archaeologist at the Hereford and Worcestershire Archaeology Section in England, analyzing ancient pottery, I had the opportunity to travel around schools of the area. At this particular time, the Roman period was entered in the school curriculum. This meant that on occasion I was able to talk to the children in a class whose age varied between eight and twelve years old about the Roman pottery which I had been working on.

At this age children are very receptive and were eager to learn, besides the fact I had the original roman pots for them to see and handle. I was delighted at their reaction and soon realized that the living history, and hands on the objects, I was demonstrating was likely to be a real boost for education purposes.

Once teachers heard of my enterprise I was called to some of the schools regularly, especially to review the homework I gave the children once I had finished talking about the different types of Roman pottery. I was amazed as the teacher had made them draw the different shapes of the vessels.

One of the children wanted to know what kind of food was cooked, and in which vessel it was cooked in. It was from this little girl’s question I decided that on my next visit to a school, I would take along with me a Roman mortarium and mix the sauce which would have been served with chicken. Their teacher had already agreed on my return visit to demonstrate this to the class. Upon my arrival, and with the ingredients needed to make the sauce, I found the history teacher was waiting with the children who were all dressed up in Roman style outfits.

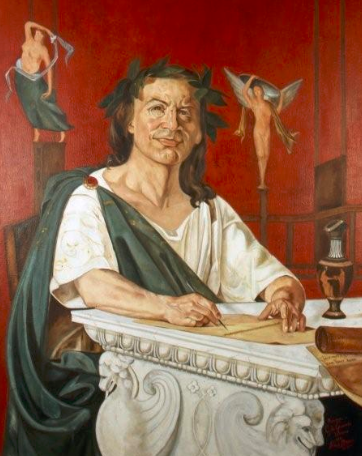

This seemed to make the children even more excited because after all, it was a living history lesson and they were eager for me to proceed. But first I needed to explain about the Roman cook Apicius.

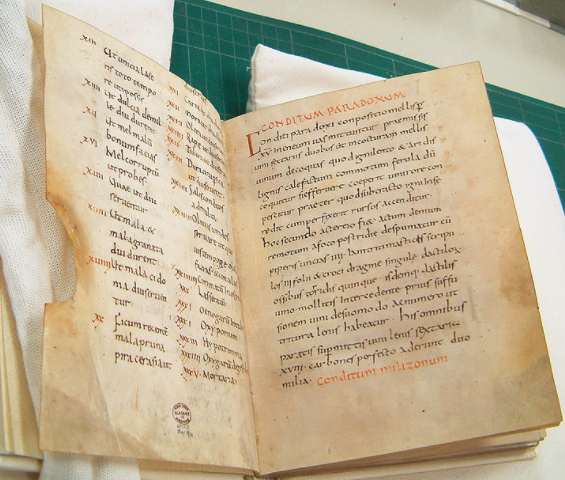

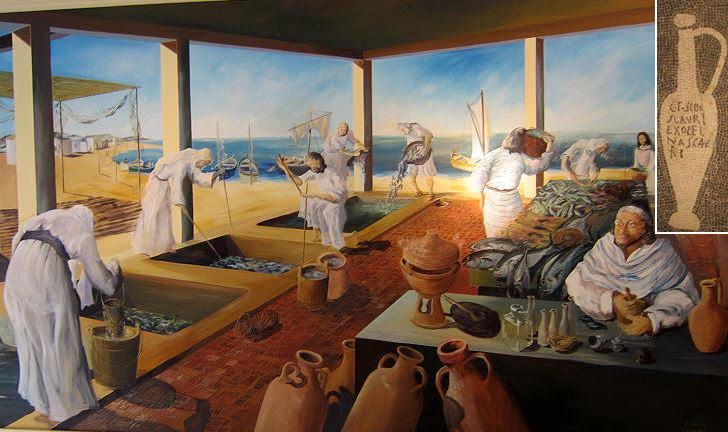

Gaius Apicius lived during the reign of Emperor Tiberius in the 1stcentury A.D. The cookery books which he wrote were published some three hundred years later and are the main source of our knowledge of Roman food.

Apicius was able to buy a large selection of herbs and spices from Roman and Greek traders who travelled to the spice markets of South Asia. These were then offered for sale in the markets of Rome. Some of the sauces made by Apicius were flavoured with up to twelve different herbs and spices. Many spices such as pepper, cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg and cloves came from India, Sri Lanka and China.

The highly flavoured sauces made by Apicius were often used to mask food which may have become stale or rancid because of over-storing. The most commonly-used seasoning was called liquamen. Apicius became a very wealthy man, but it is believed he committed suicide by poisoning himself. As a result of his buying so many expensive foods from every part of the known world, he realized that he had only about ten million sesterces left and he did not consider this enough to maintain his high standard of living.

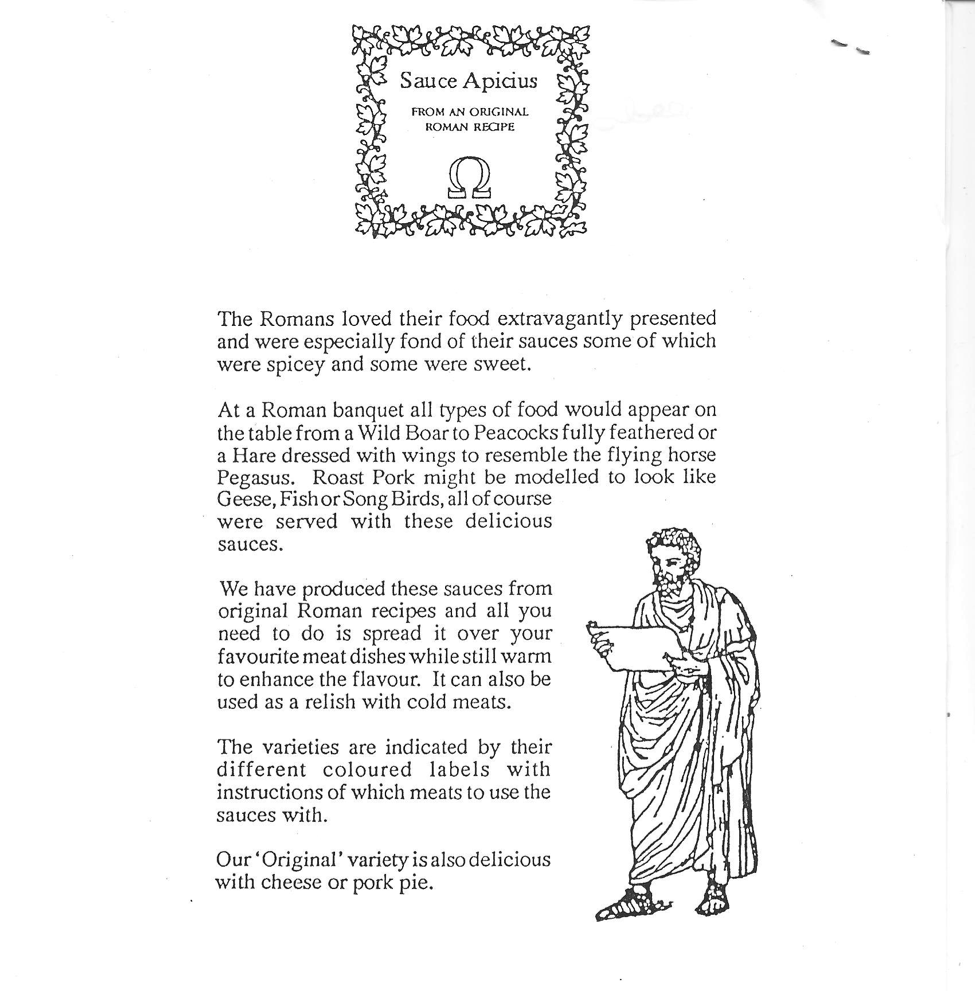

Rita always displayed this Living History leaflet on the stall at each historical venue she attended.

Procedure for Making Apicius Sauce

Once I had the ingredients displayed on the table in front of the class, the children interacted by passing the herbs and taking turns in grinding them in a Roman mortarium, after which the liquids were added. The sauce was then ready for tasting. Mr Townsend, the history teacher, had the first sample. Then one by one the pupils very gingerly came forward to taste. There were many different comments such as ‘it’s quite nice really’, or ‘better than I expected’. Some of them did not like it at all. Another said it tasted a bit like curry.

However, Mr. Townsend was quite impressed, saying it had a unique flavour and that I should market it. I thought about this but knowing there would be a lot involved such as adhering to the Trading Standards and Health and Safety regulations. But first I thought about a trial period where I could sell my produce from a stall at The Woman’s Institute, and also The Woman’s Guild, which held events all year round. This proved successful, so after passing all exams needed for Trading Standards and Health and Safety Regulations, Apicius Sauces Ltd., was launched.

I had approached many museums, historical houses, English Heritage and The National Trust who all agreed to sell Apicius Sauces in their gift shops. We were also producing a variety of sauces from other historical times by request, ranging from the Medieval to the Stuart and Tudor times. Also, we were invited to join the Re-enactors Societies with the offer of a special stall with which to trade from. Below are some photographs taken at Kirby Hall.

Rita at her stall. The jars displayed in the dish were for people to sample. The taste surprise always led them to purchase not only for themselves, but to take home for friends who could not attend the re-enactment show.