It’s been a while since our last Ancient Everyday post, so time to get back to it.

Today, we’re going to look at the father in Roman society, the paterfamilias.

As an example, we are going to use Quintus Metellus Anguis, one of the main characters from the book, Killing the Hydra.

Looking back on the writing of this book, I forget all the years of research that went into it. I take for granted the everyday Roman world I immersed myself in to write it and the rest of the series. It all seems quite normal to me now.

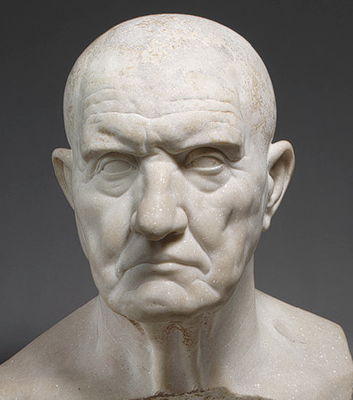

Republican portrait of a man

I’ve spent a lot of time with the characters – the good, the bad, the savage, the honourable, the beautiful, the mysterious etc. etc., but Senator Quintus Metellus Anguis was a difficult person to deal with. However, I’m not sure he would have been out of place in the early Republican era.

Quintus is a spiteful, hard man who is quick to anger and jealous of his son’s (that is, Lucius Metellus Anguis’) successes. He is of a mindset that was born in the very early days of the Republic when there were no emperors, when kings were killed, and when the father held supreme power in the family.

Then again, in some ways, Quintus Metellus could not be more out of place in early 3rd century Rome, the period during which the story takes place.

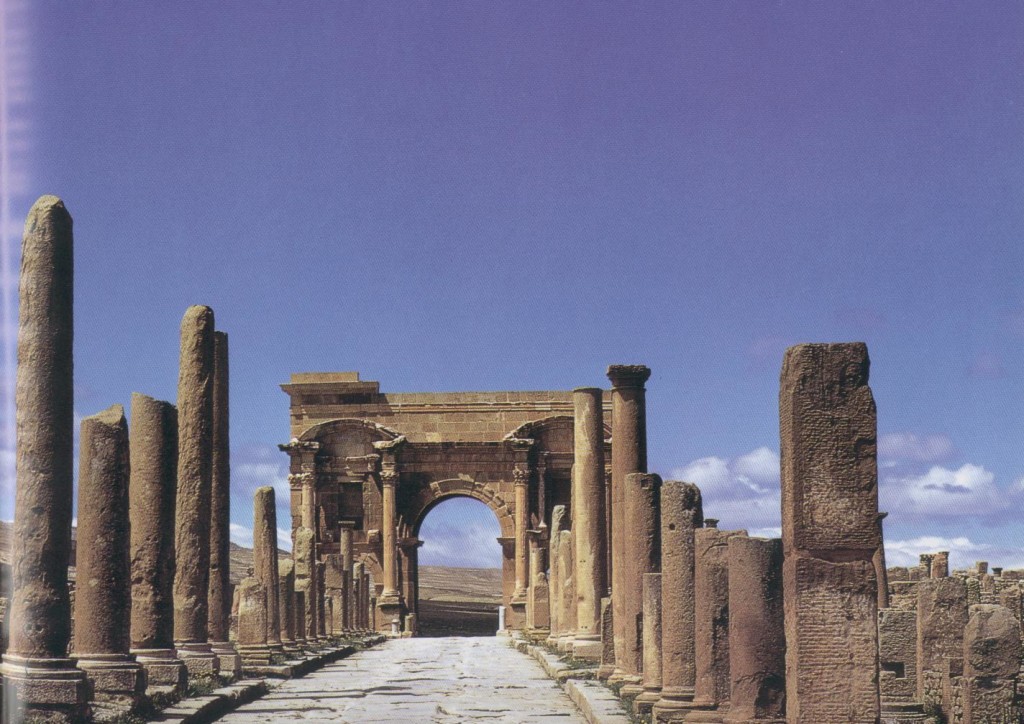

Imperial Family under Augustus

Let’s take a look at the father in ancient Rome and his role as paterfamilias.

First we should have a look at the word familia. In ancient Rome, a familia did not only include a father, mother and children. The word also referred to other relatives (by blood or adoption), clients, freedmen and all slaves belonging to the family. It included all the family houses, lands and estates and anyone involved with running those holdings.

The Roman familia went far beyond the nuclear family, and the paterfamilias was the head of it all.

Roman Man and his ancestors

During the early days of the Roman Republic, the role of the paterfamilias was largely determined by an unwritten moral and social code called the Mos Maiorum, or the ‘ways of the elders’. These governing rules of private, social and political life in ancient Rome were handed down through the generations. Because these rules were unwritten, they evolved over time. Values and social mores change, as is natural, and successive generations come into their own with ideas different to their predecessors.

The generational differences form a large part of the conflict between Lucius and his father Quintus in both Children of Apollo and Killing the Hydra.

Roman Youth – in this case, Marcus Aurelius

Quintus Metellus, as a Republican, is against Emperor Septimius Severus. He has had a vision of his son’s social and political progress since before he was born. He has tried hard all his life to breathe life back into the ancient name of ‘Metellus’, but without success. Now, all the pressure is placed upon his son, Lucius, whom he wants to become a senator of renown after he completes his minimum number of years in the military.

But Lucius has other ideas. He does not want what his father wants. Lucius has found success in the Legions and has been praised and promoted by Emperor Severus, a man he is happy to serve. Unlike many equestrian youths, Lucius Metellus Anguis is not interested in pursuing a political career. He wants to be a career officer in Rome’s Legions – something that causes his father no end of embarrassment and frustration. In his opinion, it is not the way to further the family name and better their fortunes.

In the early days of the Republic, Lucius would have had to do as his paterfamilias dictated. There would have been no choice in the matter, no influence from his mother or older sister to help his cause. The paterfamilias’ word was law within the familia.

In ancient Rome, the paterfamilias had to be a Roman citizen. He was responsible for the familia’s well-being and reputation, its legal and moral propriety. The paterfamilias even had duties to the household gods.

And this is where Quintus Metellus fails. He has lost faith in the gods that have watched over them. In fact, he fears them and their apparent favour of his son. Quintus clings to the archaic role of the paterfamilias like a dictator with power of life and death over the members of his familia. He forgets that the paterfamilias’ role is also to protect his familia within the current world they live in, and to honour their ancestors and their gods through his behaviour, his example.

This is where Lucius fills the void in duties neglected by his father.

But it is never as easy as that. The Empire is large, and most men are susceptible to corruption. Lucius fights for honour and goodness in a world that has no qualms about dismissing honour, virtue and family in the interests of greed and political advancement.

Quintus Metellus is the paterfamilias of their branch of the Metellus gens, but his own shortcomings and archaic notions are at complete odds with his son and the times they live in.

It’s always interesting to compare previous ages and practices with those of our own. Certainly the role of the father has changed over the centuries, though it varies from family to family and culture to culture.

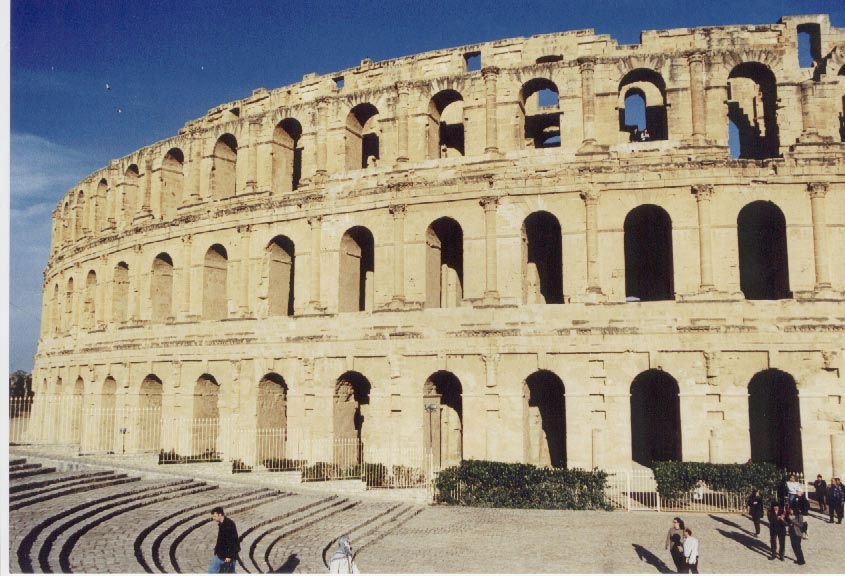

Roman husband, wife and children

Fortuna smiled on me with my own father who, thankfully, bore no resemblance to Quintus Metellus. But it was interesting to write such a character as Quintus, to explore his relationship with Lucius and the rest of the familia.

By the 3rd century A.D. the paterfamilias’ power of life and death over his family was restricted, the practice all but dead.

But old habits and ideas die hard, and for Quintus Metellus there are other ways to kill a member of your familia and maintain your power as paterfamilias.

Thank you for reading.