Caligula…

The name conjures images, doesn’t it? Oh yes – more so than Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, the full name of the Roman emperor we know as Caligula.

Caligula definitely has more power, largely due to the stories behind the name, stories of extreme debauchery, sadism, insanity and horror.

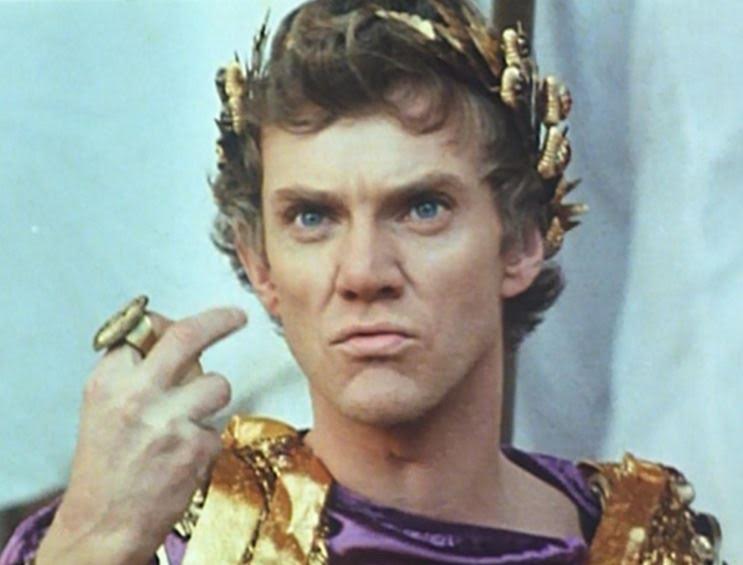

You might envisage John Hurt in the television drama of Robert Graves’ I Claudius, his mouth bloody after eating the baby which he had put in his sister’s belly, believing himself to be the god, Jove.

Or, perhaps more disturbingly, the image of Malcolm McDowell cavorts into your thoughts amid flashes of naked bodies and the bloody bits and pieces of Caligula’s victims in the infamous, star-clad film originally scripted by Gore Vidal, Caligula.

These are the images that we have of Caligula today. They’re built on ancient sources and popular culture that described the reign of this most disturbing of Roman emperors.

But is the portrayal of Caligula as an insane, perverted, and brutal emperor accurate? Is it fair?

Caligula had an interesting life as a boy. He was with his father, the Roman hero Germanicus, and the army along the northern frontier camps. Among the men of the Legions, it’s said, he got his nickname. ‘Caligula’ is a diminutive version of the word for military, hobnailed boots called caligae. He became ‘Little Boots’ because of the smaller pair of caligae he wore around the camp.

Was Caligula a cute little boy? Odd to think after all the rumours. The troops seemed to have adopted him.

His life took a turn for the worst though, leaving him one of the sole survivors of his family.

There were rumours that Tiberius or Livia, Augustus’ empress, may have been responsible, more or less, for killing Caligula’s family, including his hero father, Germanicus. However, most now seem to agree that this was unlikely, that it was due to natural causes in the East. Another rumour was that Germanicus was poisoned by Gnaeus Piso, who was put on trial for it.

Either way, ‘Little Boots’ ended up spending a lot of time with his great uncle, Tiberius, on the island of Capri. This island is where the Emperor retreated in his advanced years, and it’s rumoured that much depravity took place there, and that Caligula learned that behaviour.

Oddly enough, the first six months of Caligula’s reign as emperor were said to be good and moderate. He fell seriously ill around that time, however, and afterward the chroniclers speak of a young man who believed himself divine, and who became the most cruel, extravagant and perverse of tyrants. Did the illness alter his mind in some way? We may never know.

I’m not an expert on the reign of Caligula and, in fact, it seems that few people are.

Caligula’s reign as Roman emperor is one of the most poorly documented in Roman history.

Since that is the case, it seems understandable that countless generations would cling to the tales told by Suetonius so many years after Caligula’s death: that he had sex with his sister on a regular basis, that he made his horse a consul, and that he forced senators’ wives to have sex.

If you can make it up, it probably fits the historical and pop-culture bill when it comes to Caligula.

The other side of the argument says that all of the salacious tales were invented, pure fabrications created by Caligula’s, and the Julio-Claudian’s, enemies.

Perhaps. But must not there be some basis in fact?

Certainly, the senatorial and Praetorian conspirators behind the assassination of Caligula (he was the first emperor to be assassinated) needed to justify their actions.

Some believe that Caligula had tried very hard to increase the power of the Emperor and further minimize the Senate. This would make him a lot of enemies – enemies who would write the history of his reign long after his death.

There is real power in writing after the fact – which is why we must approach any source, modern or historical, with a degree of caution.

Even our views of the most famous and popular (even well-documented) figures of history can be flawed. History is written by the victors, or at the least by the survivors. Everyone, especially emperors, had enemies, even if they were ‘good’ or ‘bad’ rulers.

Popular media, such as film and fiction, can reveal to us certain aspects of historical people, but we must take everything with a grain of salt. We have to accept that what we are reading or seeing might be based on subjective sources that had a particular goal in mind.

However, learning how a generation of people viewed a particular person (even though the stories may not be true) can also be useful. Their hatred, love or fear etc. must have come from somewhere!

Was Caligula as mad as they say or as we believe? Perhaps.

His depravity has made some good storytelling over the centuries. I suspect that some of it is true. But, like all good stories, things have been elaborated on for sheer entertainment value, especially when the man himself was safely dead.

I highly recommend Robert Graves’ I Claudius if you have not already read it. It’s a modern classic, as is its television dramatization starring John Hurt and Derek Jacobi. It’s a wonderful piece of fiction, if not entirely accurate.

On the other hand, if you have the stomach and libido for it, the film version of Caligula is a terror-filled, pornographic representation of Caligula that brings all of the most salacious tales of him to life. A warning: this film is not for the faint of heart.

But let’s get back to an original source…

We should end with a quote from Suetonius who seems to be one of the main sources of all the tall tales that have been passed down the ages:

“…he (Caligula) could not control his natural cruelty and viciousness, but he was a most eager witness of the tortures and executions of those who suffered punishment, revelling at night in gluttony and adultery, disguised in a wig and a long robe, passionately devoted besides to the theatrical arts of dancing and singing, in which Tiberius very willingly indulged him, in the hope that through these his savage nature might be softened. This last was so clearly evident to the shrewd old man, that he used to say now and then that to allow Gaius to live would prove the ruin of himself and of all men, and that he was rearing a viper for the Roman people and a Phaethon for the world.” (Caius Suetonius Tranquillus; Lives of the Twelve Caesars)

As I said, history is written by the survivors, and as it is, history remembers Caligula as a sadistic, incestuous maniac who thought he was a god, who made his horse a senator, cared nothing for the power of the senate, and went to war against the god Neptune. The damning list goes on and on…

On the other hand, he undertook several public building projects and expanded the Empire’s borders in North Africa.

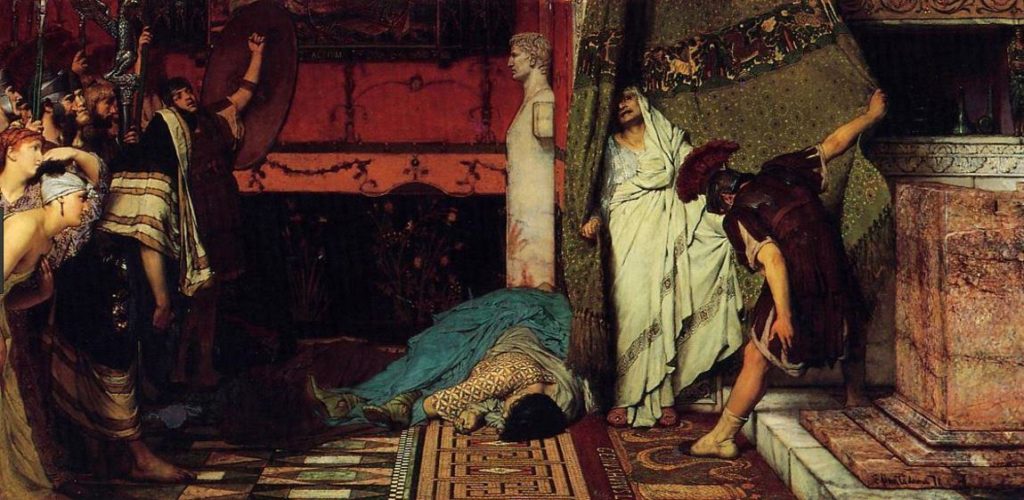

But, in the end, Caligula was murdered by the Praetorians who immediately made Claudius the next emperor.

Will we ever know the true nature of Caligula?

Probably not, but this certainly is an instance in which the history, true or not, is highly entertaining and shocking.

Thank you for reading.

Emperor Claudius – (Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1871) – with the murdered Emperor Caligula on the floor at Claudius’ feet

What are your thoughts on Emperor Caligula? Was he as vile as portrayed? Or was he the victim of malicious gossip?

For those of you who want to read a bit more, check out this interesting article on the BBC website by CLICKING HERE.