Greetings Readers, Hellenophiles, and Romanophiles!

Eagles and Dragons Publishing is proud to present an all new ‘World of’ blog series that will take a look at the research, people, and places related to the newest book in The Etrurian Players series, An Altar of Indignities: A Dramatic and Romantic Comedy of Ancient Rome and Athens.

In this blog series, we’ll be looking at a wide range of topics such as theatre, ancient Athens, festivals, religion, playwrights, customs and more.

And now, without further ado, let’s step into The World of An Altar of Indignities!

The Theatre of Epidaurus

Part I – Drama and Theatres in Ancient Athens

In this first post, we’re going to be taking a brief look at drama and theatres in ancient Athens.

But this book is set during the Roman era, isn’t it? you might ask.

That is true, but the Romans were the inheritors and adopters of Greek theatrical traditions and, as the book is set in Roman Athens, we thought it would be good to start with a look at the birth of drama in ancient Greece.

Tragedy is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude…through pity and fear effecting the proper purgation of these emotions.

(Aristotle, Poetics)

In the West, we owe a great deal to the ancient Greeks, particularly the Athenians. Out of ancient Greece came epic poetry, and lyric poetry sung to music. There was elegiac poetry that expressed personal sentiments of love, lamentation, and military exhortations. Epigrams memorialized the dead in inscriptions across the Greek world. Iambic poetry relayed often satyrical ideas as close to natural speech as possible, and bucolic poetry in hexameter told stories of the lives of ordinary country people rather than of heroes.

There is much more to it, but you get the idea. Basically, all of our western literary traditions came out of Ancient Greece.

Not least among these genres was drama.

Relief of Maenads in ritualistic, frenzied dance honouring Dionysus.

The first thing we should look at is how the artform of ‘Drama’ came about as a form of entertainment.

Similar to gladiatorial combat in Ancient Rome, which began as a religious ritual for the dead, drama in Ancient Greece was born out of religious practices, in particular, rituals honouring the god, Dionysus.

Early worship to Dionysus involved a darker side with ecstatic worship by female followers – the maenads of mythology – who were said to partake in frenzied dances and tear into animal, and sometimes human, flesh. In the sixth century B.C.E the worship of Dionysus involved obscene play, extreme emotion, singing, and dancing.

This was the genesis of Greek drama.

It was the tyrant Peisistratos (c. 600-527 B.C.E) who founded the city Dionysia of Athens, the great festival in honour of Dionysus, which involved a chorus of men singing and dancing for the god. Later, there were also rural Dionysia about Attica, with similar rituals. These early choruses could be as large as fifty people, but most were believed to consist of twelve to fifteen members.

In the sixth century (c. 535 B.C.E), when a man named Thespis added himself to the ritual to deliver a prologue and interact with the Dionysian chorus, he is said to have become the very first actor, or ‘thespian’.

The addition of this one person to interact with the chorus is thought to be the beginning of true drama, the transition from religious ritual to dramatic performance for an audience.

Later, the playwright Aeschylus added a second actor and, after him, Sophocles added a third, and this became the standard number of actors for a while, in addition to the members of the chorus.

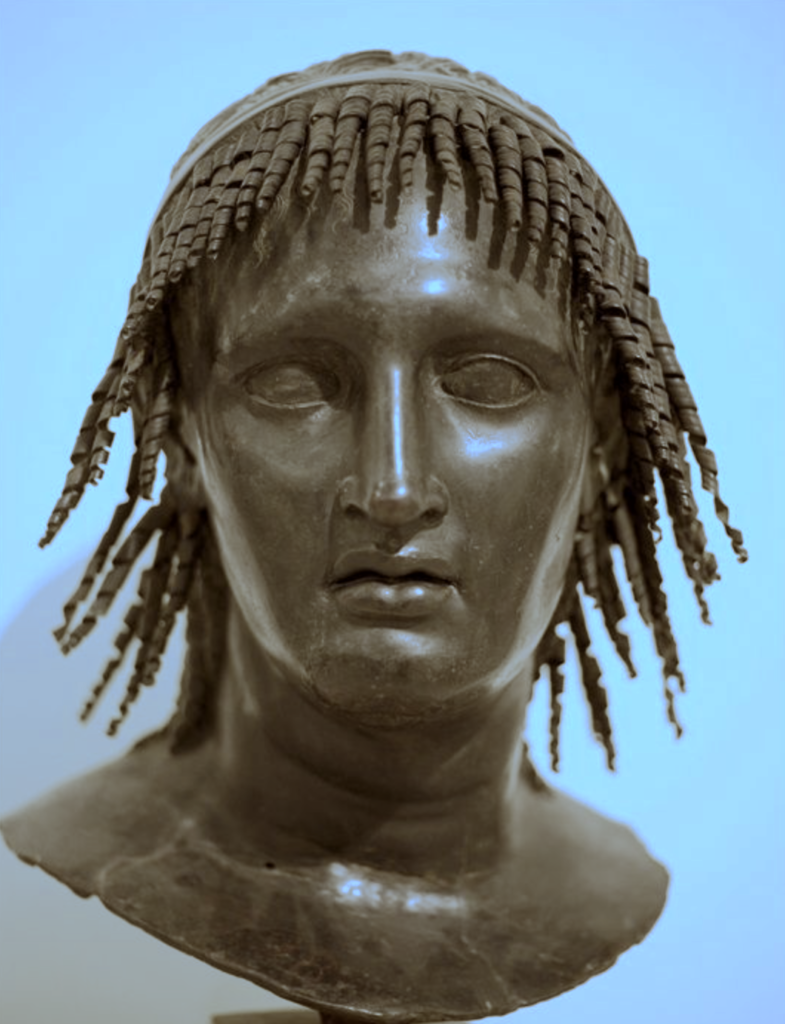

Roman bronze from Herculaneum thought to represent Thespis, the first actor.

In early drama, Greek comedies and tragedies were, more or less, musical productions. This was due to drama’s origins in dance and song for Dionysus. The members of the chorus played groups of people like the citizens of a city, dancing and singing.

These new dramas or plays, until the Hellenistic age, were performed in competitions as part of religious festivals like the Dionysia, the Lenaea (a winter festival to Dionysus), and the Panathenaea (to Athena Parthenos) at Athens. These theatre festivals were organized by the state.

For festivals, usually three poets were selected to have their work performed, and they were assigned an actor, or actors. The playwrights who participated wrote either tragedy or comedy, but not both. They usually submitted three tragedies on different themes and a satyr play, a short comedic piece (ex. Euripides’ Cyclops).

The winner of these competitions received a wreath. From about 499 B.C.E, the best actor also received a prize. All actors, even those playing female roles, were men. Oftentimes, the poets also acted in their own plays.

At Athens, when the Dionysia was in its infancy, the admission to watch the dramas was, apparently, about two obols. However, when Pericles was leading the way through Athens’ Golden Age, the state began to pay for admission to the theatre. In addition to male citizens, this sometimes also included non-citizens, or metics, as well as women and children who were, of course, accompanied by well-respected male citizens.

But before we get into the role that theatre played in Greek society, let’s first take a look at the types of drama that were performed, mainly Tragedy and Comedy.

It should be said at this point that, unfortunately, very little ancient drama has survived the centuries, and when it comes to tragedy, only Attic tragedies have survived.

Tragic dramas or plays from Ancient Greece seem to have originated in the mid-sixth century B.C.E in Attica or the Peloponnese, and the earliest surviving one we have is Aeschylus’ Persians (c. 472. B.C.E).

Ah! Miserable Fate! Black Fortune!

Black, unbearable, unexpected disaster!

A savage single-minded Fate has ravished the Persian race!

What troubles are still in store for me?

All strength has abandoned my body… my limbs… there is none left to face these elders.

Ah, Zeus! Why has this evil Fate not buried me, as well, send me to the underworld, among all my men?

(Aeschylus, Persians)

Tragedies were the first dramas and they were almost all based on mythological tales of gods, goddesses and heroes. They also had a standard format that comprised a prologos, sometimes presented by the chorus, and sometimes by an actor. Then there was a monologue or introduction. There was a parados, which was a song sung by the chorus as it entered. After that, there were various epeisodia, scenes with actors and the chorus, and during these epeisodia, stasima (songs) were performed. The play usually closed out with the exodos, the final scene or ‘exit’.

So, the first dramatic performances were tragedies and the genre gave rise to some of the most famous playwrights of the ancient world, including Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. However, tragedy began to decline by the end of the fourth century B.C.E in favour of comedy.

Melpomene – The Muse of Tragedy

The word comedy is derived from the Greek komoidia which comes from komos, a procession of singing and dancing revellers.

It is believed that comedy dates to the sixth century B.C.E and that it may have its roots in Sicilian or Megarian drama.

As with the tragedies, only Attic comedies survive to this day, and the earliest surviving one we have is Aristophanes’ Acharnians (c. 425 B.C.E). There were earlier comic poets such as Cratinus, Crates, Pherecrates, Eupolis and Plato (different to the famous philosopher), but none of their works survive.

Oh! by Bacchus! what a bouquet! It has the aroma of nectar and

ambrosia; this does not say to us, “Provision yourselves for three

days.” But it lisps the gentle numbers, “Go whither you will.”

I accept it, ratify it, drink it at one draught and consign the

Acharnians to limbo. Freed from the war and its ills, I shall

keep the Dionysia in the country.

(Aristophanes, Acharnians)

Ancient Greek comedy can be separated into three different types: Old Comedy, Middle Comedy, and New Comedy.

Comedies were humorous and uninhibited with many jokes about sex and excretions. They ridiculed and parodied contemporary characters, and an excellent example of this is Aristophanes’ ridiculing of Socrates in Clouds:

A bold rascal, a fine speaker, impudent, shameless, a braggart, and adept at stringing lies, and an old stager at quibbles, a complete table of laws, a thorough rattle, a fox to slip through any hole, supple as a leather strap, slippery as an eel, an artful fellow, a blusterer, a villain, a knave with one hundred faces, cunning, intolerable, a gluttonous dog.

(Aristophanes, Clouds)

Comedies also made fun of contemporary issues as well as gods, myths, and even religious ceremonies, making it a sort of acceptable outlet for mocking things that were otherwise sacred. This was a form of ‘free speech’ at work in the new Democracy of Athens.

All performances were staged during the city Dionysia and the Lenaea in Athens.

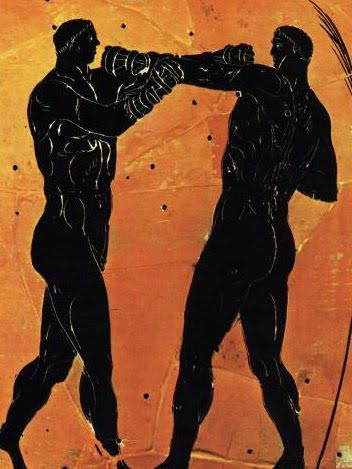

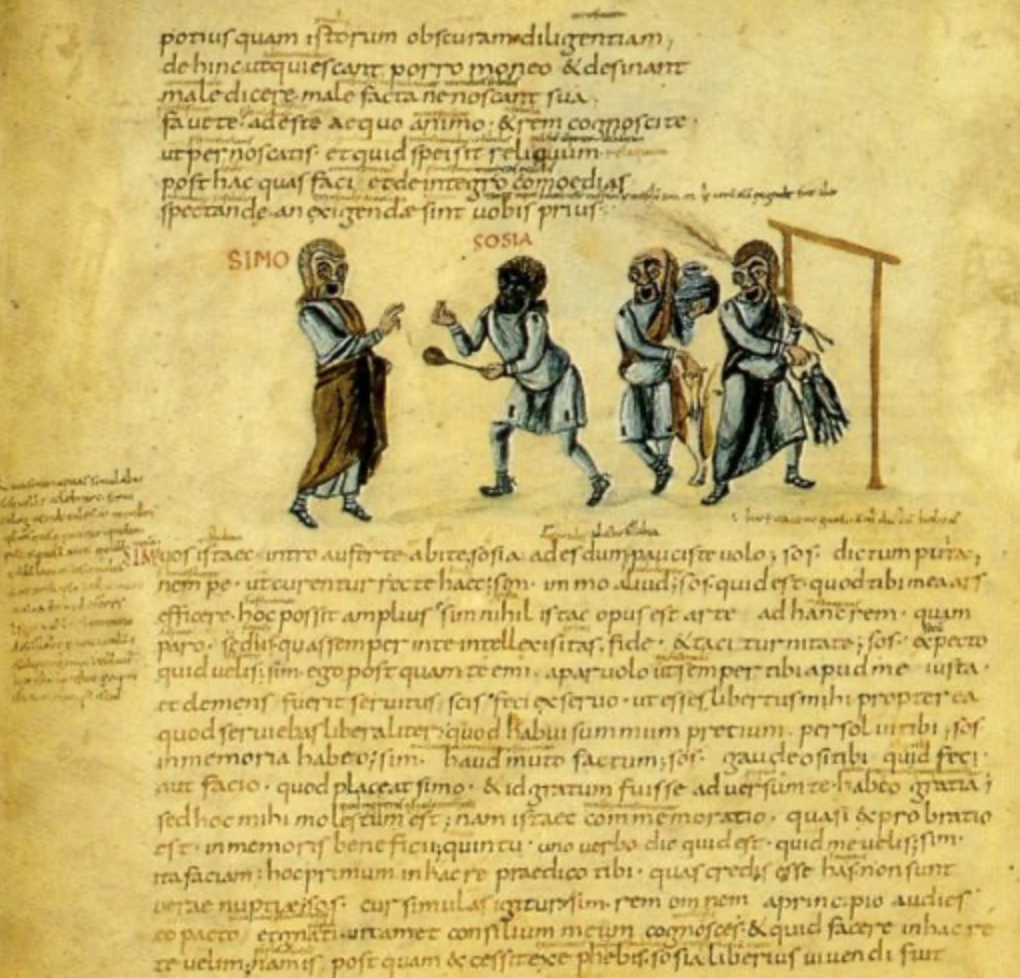

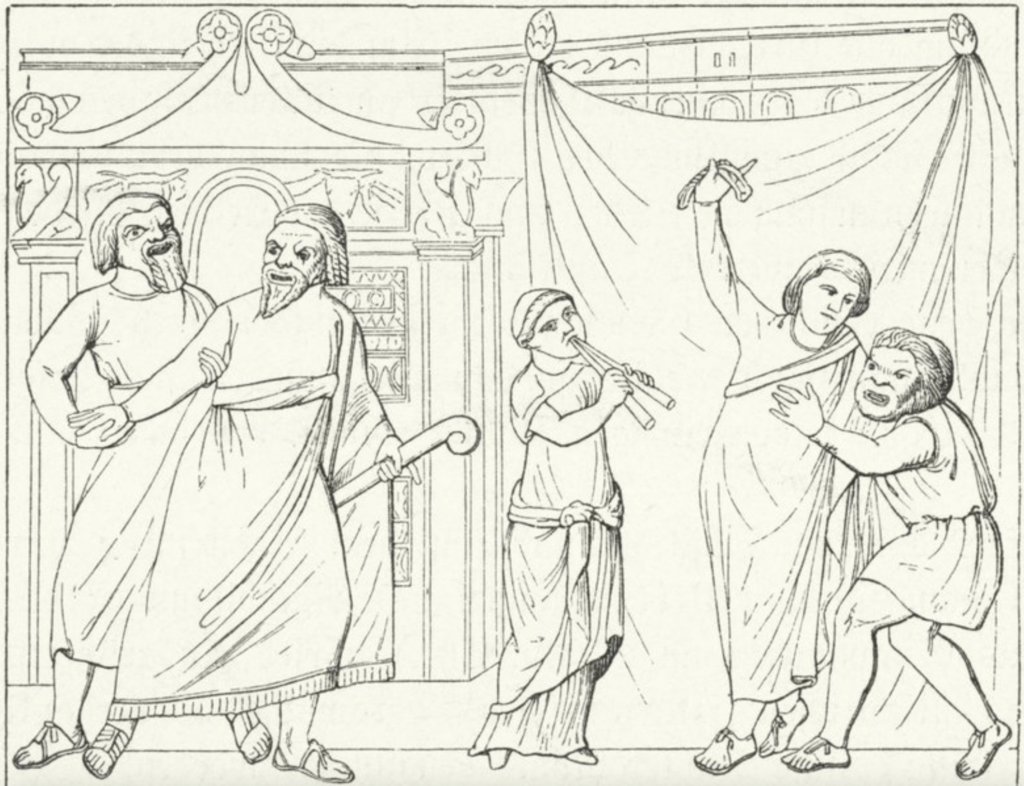

Old Comedy consisted of choral songs alternating with dialogue but it had less of a pattern than tragedy did. The chorus consisted of about twenty-four men and extras, and they often played animals. The actors wore grotesque costumes and masks.

Old comedies began with a prologos, and then the entrance of the chorus which proceeded to sing a parados, a song. Then there was the main event, the agon, a struggle, which was a debate or physical fight between two of the actors. There were songs during the action and subsequent scenes or epeisodia. The chorus also uttered a parabasis, which was a blessing on the audience. As with tragedy, comedies also ended with the final scene, or exodos.

Second century C.E. mosaic depicting dramatic masks for Tragedy and Comedy

Middle Comedy in Ancient Greece was basically Athenian comedy from about 400-323 B.C.E. It developed after the Peloponnesian War and was more experimental with different styles beginning to emerge. Apparently it became quite popular and experienced a revival in Sicily and Magna Graecia.

Comic choruses began to play less of a role, and the parabasis was no longer used. Interestingly, the more grotesque costumes and phalluses were not as popular either.

Comedic plots based on mythology and political satire began to give way to less harsh humour and a focus on ordinary lives and issues.

Sadly, no complete plays from Middle Comedy survive, but some of the authors we know of were Antiphanes, Tubules, Anaxandrides, Timocles, and Alexis. Some might also class Aristophanes as one of the earliest poets of Greek Middle Comedy.

Thalia – The Muse of Comedy

Lastly, New Comedy is generally considered to be Athenian comedy from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C.E to about 263 B.C.E.

In New Comedy performances, plays were five acts long and were interspersed with unrelated choral or musical interludes. They were generally set in Athens or Attica, and the actors wore masks, but now dressed in regular everyday clothes.

Though new comedies were Athenian, writers came from around the broader Greek world to Athens to write, and to see the plays.

The themes of these new plays were more human and relatable and dealt with things such as family relationships, love, mistaken identities (a throw-over from Middle Comedy), the intrigues of slaves, and long-lost children.

There were also stock characters that emerged such as pimps and courtesans, soldiers, young men in love, genial old men, and angry old men.

The themes and characters of Greek New Comedy greatly influenced Roman drama and which became so popular for the Roman theatre crowd.

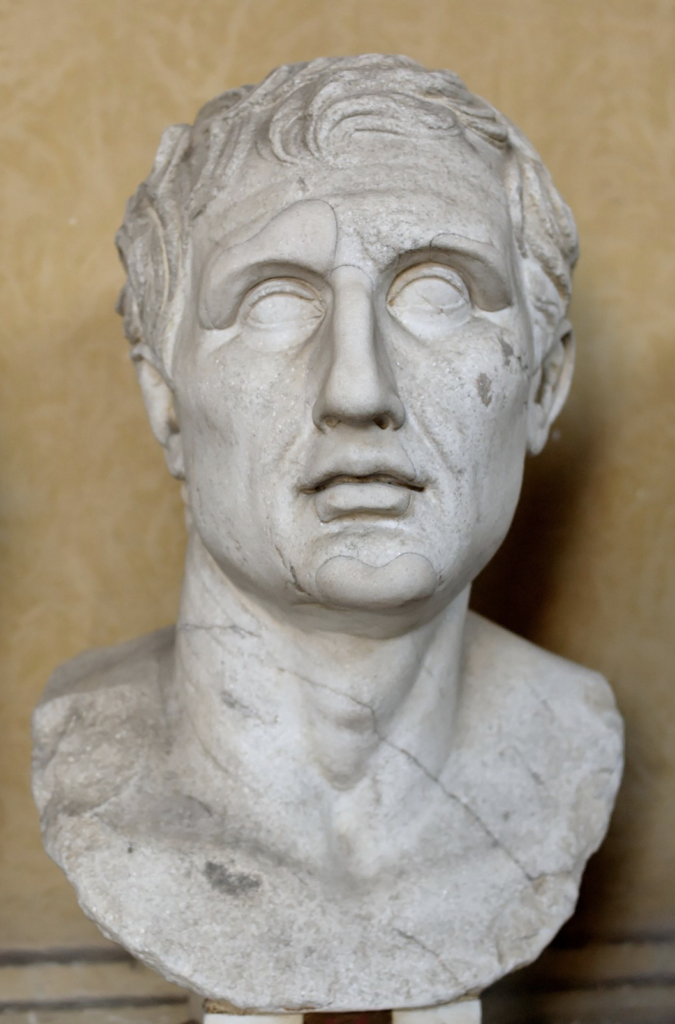

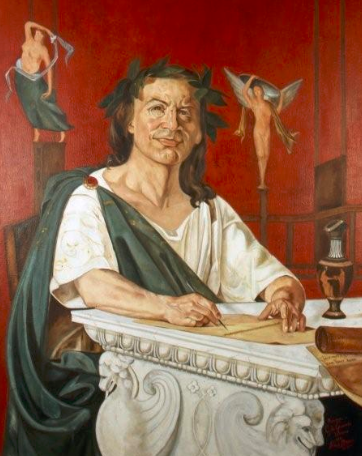

Menander (c. 343–291 B.C.E)

Sadly, little survives in the form of Greek New Comedy, but much Roman comedy such as plays by Plautus and Terence, were based on those Greek plays, particularly Menander (c. 341-290 B.C.E). Other authors included Diphilus and Philemon.

It is a true tragedy that so much comedy does not survive. Menander alone is thought to have written over one hundred plays, and yet only a small fragment of a single one of his plays survives.

Thankfully, Roman playwrights such as Plautus and Terence used Menander’s plays as blueprints for their own and, as a result of that New Comedy format and formula, they gave rise to the western comedic tradition we are familiar with to this day through Shakespeare, Moliere, and others.

Now that we have briefly touched on the history of drama and plays, let’s take a look at where these plays were actually performed.

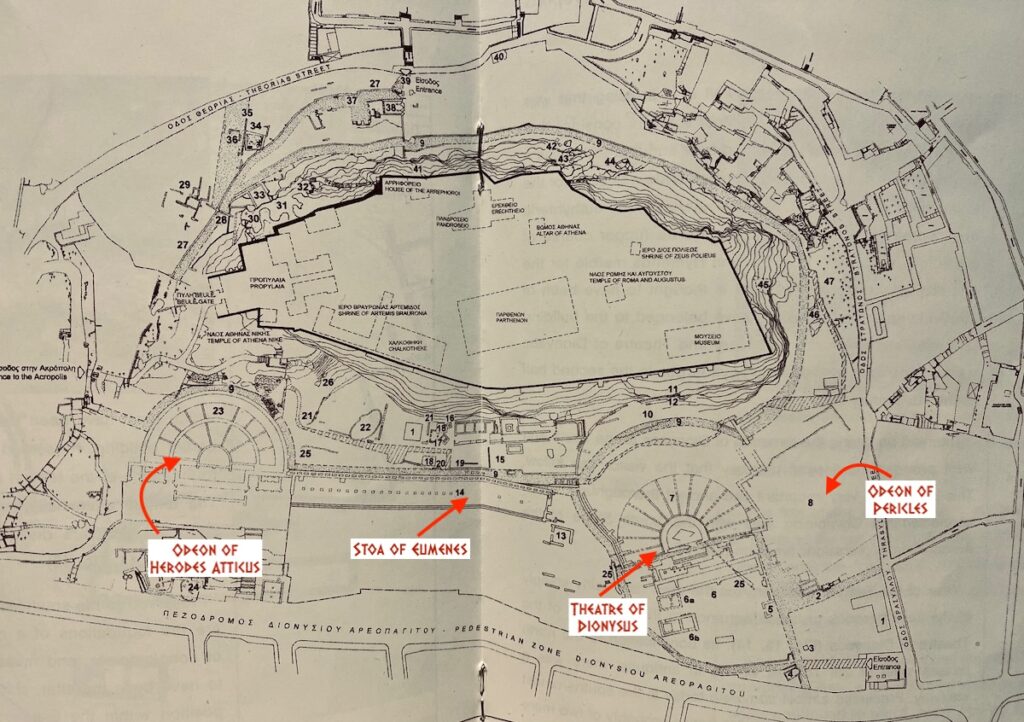

The Theatre of Dionysus, Athens

The word ‘theatre’ comes from the Greek word theatron which literally means ‘a place for watching’.

Theatres were built from the sixth century B.C.E onward. Most religious sites had a theatre and, as previously mentioned, they were used to celebrate festivals in honour of Dionysus.

Greek drama grew out of these religious festivals.

Early theatres could be temporary wooden structures, or a sort of scaffolding, but this practice was ceased after a deadly collapse in the Agora of Athens in about 497 B.C.E. After that, performances in Athens moved to the hillside where the theatre of Dionysus was built on the south slope of the Acropolis.

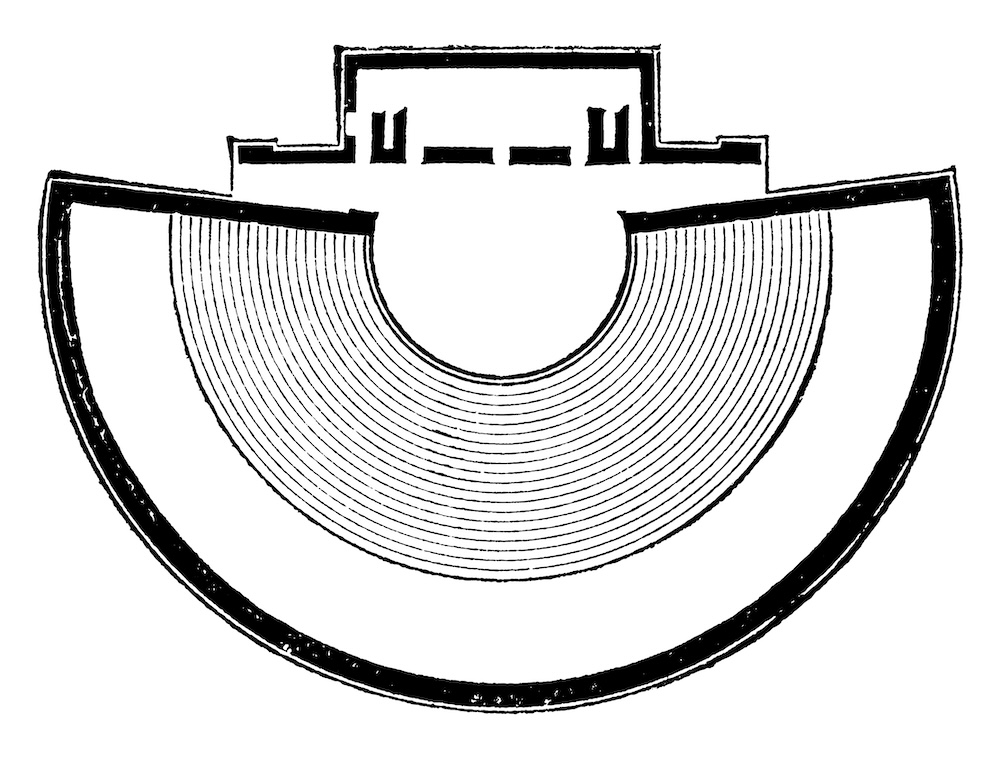

It became common practice to build theatres into the slopes or hillsides of natural hollows or, alternatively, into man-made embankments which supported tiers of seats on the hillside. Beginning in the fourth century B.C.E, theatre seating was built in marble. Theatres were generally D-shaped or on half-circle plans.

Ground Plan of the Ionian Greek theatre at Iassos.

All theatres where drama was performed were ‘open-air’ and had several common components: the koilon (the seating area) where the seats in the front row were reserved for priests and officials, the orkestra (the circular performance space), and the skene (a building for storage and changing rooms for actors). Later, the skene became a stage with a backdrop called the proskenion (in Latin, the scaena frons). The addition of this stage (pulpitum in Latin) expanded the performance area.

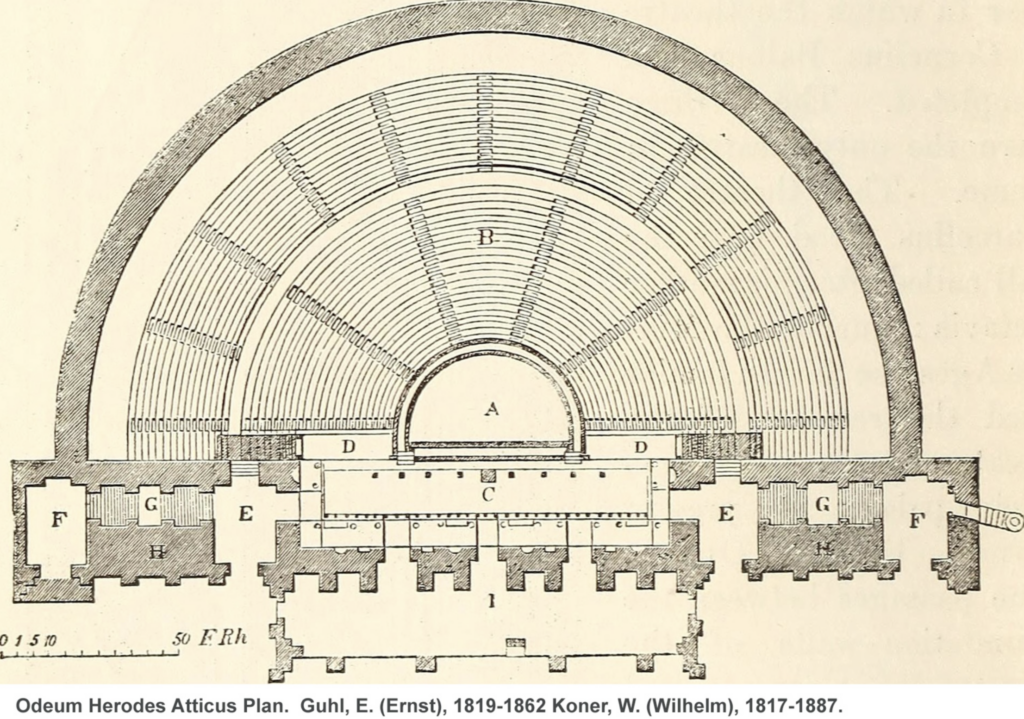

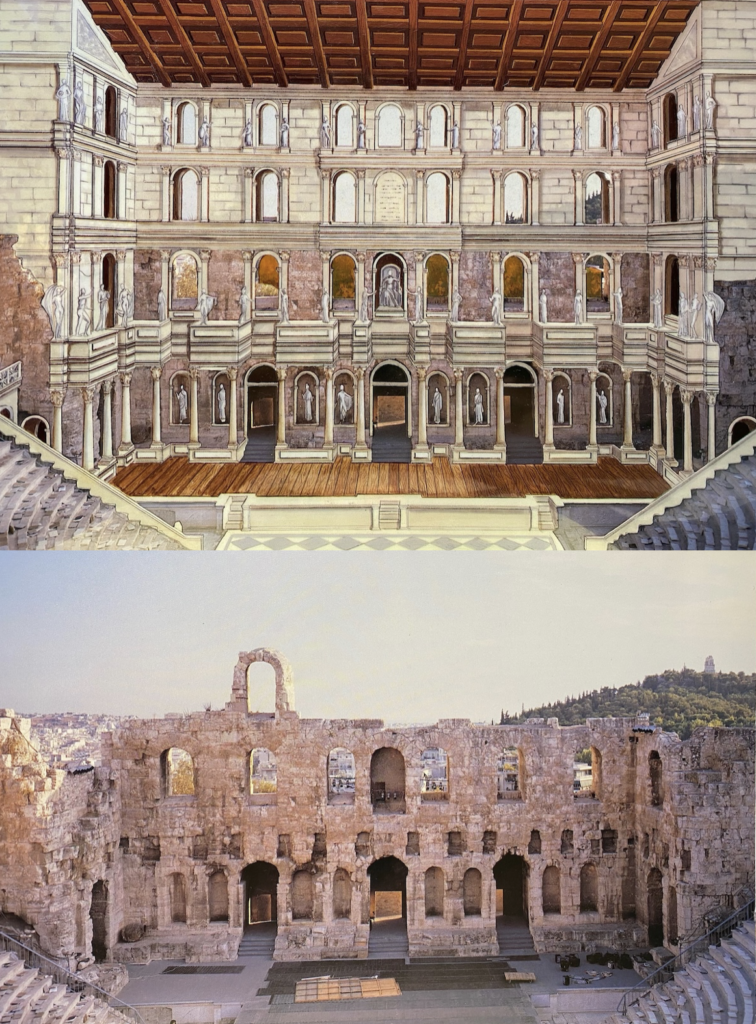

The other common performance space that was similar to theatres in Ancient Greece was the odeon (plur. odeia). These were usually roofed structures for listening to musical recitals and contests, poetry readings and other similar performances. Odeia were basically small theatres with a roof.

The first odeon of ancient Athens is thought to be that built by Pericles in the fifth century B.C.E. It was located directly beside the theatre of Dionysus and was a pyramidal structure made of wood with the roof supported by many columns. Some believe it was designed to resemble the tent of the defeated King of Persia.

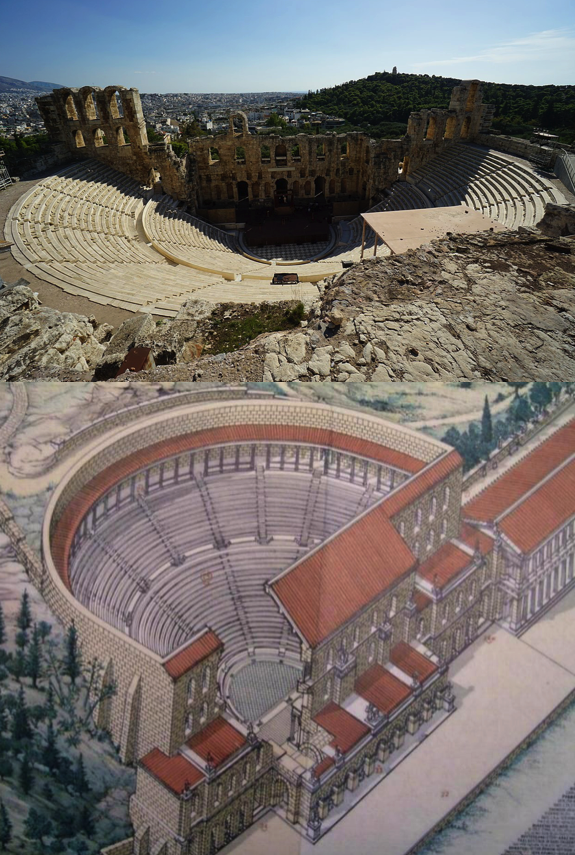

Other odeia of ancient Athens included the Odeon of Agrippa in the Athenian Agora, and the stunning Odeon of Herodes Atticus on the southwestern slope of the Acropolis which is still used for performances to this day and which is featured in An Altar of Indignities.

Acropolis of Athens with the Odeon of Herodes Atticus before it on the left.

Today, theatre and dramatic performance is seen as more of a luxury in western society, something for the privileged few.

This was not the case in ancient Athens.

Though drama had religious beginnings, it evolved into an important way for Greeks as a society (albeit mostly for male citizens) to investigate the world in which they lived and what it meant to be human.

Aristotle believed that drama, tragedy in particular, had a way of cleansing the heart through pity and terror. It could purge men of their petty concerns and worries and, with this noble ‘suffering’, they underwent a sort of catharsis.

With the advent of philosophical thought, theatre and drama became the vehicle that encouraged average Greeks to become more ‘moral’ by helping them to process the issues of the day through both Tragedy and Comedy.

Rather than being a leisure activity for the elites, as it is perceived today, attending the theatre in ancient Athens was an important form of civic engagement after exercising one’s rights and performing one’s duties for the community (such as voting). Watching and experiencing tragedies and comedies with one’s fellow citizens became an important activity in the new Democracy of the day.

Not only did the drama and theatres of ancient Athens inspire their Roman successors, they also helped to shape the artistic traditions of western civilization.

For that, we should all be grateful.

Thank you for reading.

An array of Greek theatre masks

We hope that you’ve enjoyed this short post on drama and theatres in ancient Athens. There is a lot more to learn on this subject. We highly recommend the documentary series by Professor Michael Scott, Ancient Greece: The Greatest Show on Earth. You can watch the first episode HERE.

You can also read our popular articles on Theatres in Ancient Rome and Drama and Actors in Ancient Rome.

Part II – Travel and Transportation in the Roman Empire

Map of the Roman Empire at its greatest extent (Oxford Research Encyclopedias)

The Etrurian Players – the tumultuous theatre troupe of our story – regularly travel the Mediterranean Sea to get to the location of their next performance, be it in the cities of Iberia, the great polis of Alexandria or, as is the case in this story, the city of Athens where theatre was born.

But how easy is it for The Etrurian Players to get from one place to another while on tour? How did ancient Romans, and Etrurians for that matter, get about?

Travel is something that we take for granted today. We decide we need to get somewhere, and we just go, be it nearby, or over a great distance across oceans and continents. We often take it for granted in fiction too. Characters often need to get from point A to point B, and it happens.

But in the ancient world, travel wasn’t so easy. It required planning, and it took time.

There were also many factors involved such as destination, budget (not unlike today), mode of transportation, and time of year. Unless one was a soldier, or merchant, or someone wealthy, chances are that you might never have left your community or indeed your Etrurian latifundium!

So, when people did travel in the Roman Empire, how and why did they do so?

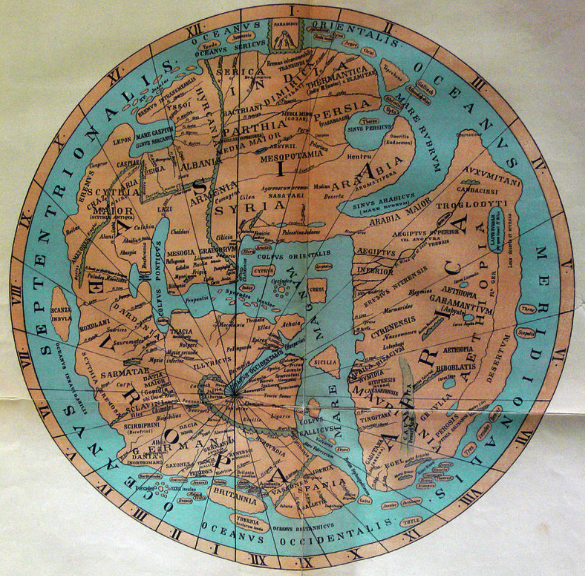

Ptolemy’s world map, reconstituted from Ptolemy’s Geography, circa AD 150, in the 15th century, indicating Sinae, China, at the extreme right. (Wikimedia Commons)

First off, we should probably discuss maps. We use maps today, and the Romans had maps. Geography was important, especially if you were planning a large scale invasion or military campaign, or even surveying for a new settlement. Not many maps from the Roman period survive, but copies of maps were made from originals. Sometimes they were even rendered in paintings or mosaics.

Maps, geography and cartography are mentioned by some ancient authors such as Strabo, Polybius, Pliny the Elder, and Ptolemy. We also know that large wall maps of the world were commissioned by Julius Caesar, and then by Agrippa, during the reign of Augustus.

Much of our knowledge of place names and geography from the Roman world comes from what are called ittinerarium pictum which were travel itineraries accompanied by paintings. Perhaps the most well-known of these is Ptolemy’s Geography which included six books of place names with coordinates from around the empire, including faraway places such as Ireland and Africa.

Another source is the Ravenna Cosmography. This was a compilation of documents by a cleric at Ravenna around 700 C.E. This particular source gives lists of stations, river names and some topographical details as far away as India.

Details of a map based on the 11th century Ravenna Cosmography (Wikimedia Commons)

The Notitia Dignitatum is a late Roman collection of administrative information which included lists of civilian and military office holders, military units and forts. The maps that accompanied this were medieval, but it is believed that they were derived from Roman originals of the fourth and fifth centuries C.E.

Perhaps the most important surviving example of an itinerary, however, is the Itinerarium Antoninianum, the ‘Antonine Itinerary’, which was a collection of journeys compiled over seventy-five years or more and assembled in the late 3rd century. It describes 225 routes and gives the distances between places that are mentioned. Some believe it was probably used for travel by emperors or troops. This particular source also included a maritime section with sea routes entitled Imperatoris Antonini Augusti itinerarium maritimum. The longest route in this itinerary appears to represent Emperor Caracalla’s trip from Rome to Egypt in about 214-215 C.E, about ten years after An Altar of Indignities takes place.

Map of Roman Britain based on the Antonine Itinerary, plotted by William Stukeley in the 1700s using the Itinerary as its source. (University of Kent)

Next, one cannot discuss travel in the Roman Empire without talking about roads.

There is a reason the expression ‘All roads lead to Rome’ exists. It was true, at least for a time. This is believed to have originally referred to the milliarium aureum, the ‘golden milestone’ near the temple of Saturn in the Forum Romanum, from which all distances were measured. It is believed that distances to specific cities or settlements were written upon it.

Part of the Via Egnatia near Kavala, Greece

When it comes to roads, Rome was the best. In fact, Roman roads forever altered the empire and travel itself. Not only did Roman roads make troop movements much easier – with the troops building the roads themselves! – but they also opened up parts of the empire to trade and further settlement. They spread out from Rome like a titanic spider web connecting the eternal city to the farthest outposts.

There were also various types of road too, not just the broad, paved roads upon which vehicles and legions could travel. There were also small tracks, causeways, narrow streets, embanked roads or strata, lanes and more. Whether you were crossing the world, or crossing a settlement, roads of all types were useful.

The Roman empire in the time of Hadrian, showing the network of main Roman roads. (Wikimedia Commons)

Of course, with Roman roads, came Roman bridges over rivers that might have added days to a journey in order to reach a suitable crossing point. Travel was shortened in many ways by using Roman roads.

Now that we know how important roads were to the Roman Empire, how did people travel upon them?

When it came to the legions, marching was the order of the day for most troopers, and the average Roman soldier, fully laden, could travel up to 25 Roman miles in one day. For the average person living within the bounds of the empire, walking was also the norm. This mode of travel was slower, to be sure, though roads made it much easier.

Apart from walking, there were of course other, faster modes of transportation such as by horse, pack animal, two-wheeled cart, and four-wheeled wagon. Obviously, these required one to have the funds to own or rent such animals and vehicles, but they did greatly cut back on the travel time.

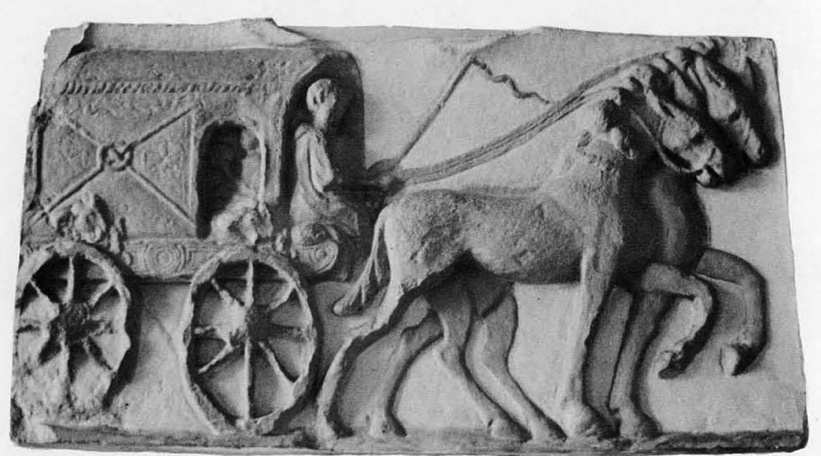

A Roman relief showing a four-wheeled, covered wagon (photo – Penn Museum)

The time of year and the weather were obvious factors when it came to travel upon roads, but also when it came to water routes open to travellers such as by river, open sea, and coastal sea travel.

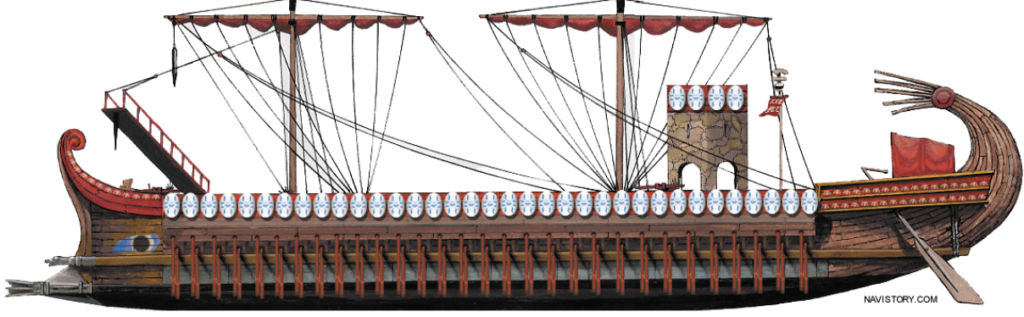

When it comes to seafaring, the Romans had no such tradition until after the wars with Carthage which forced them to come to terms with the need for a navy. With the creation of that navy, Roman troops could be moved more quickly from Rome to Africa, for instance.

The other reason for travelling by sea or waterway was, perhaps more importantly, trade. The Roman Empire at its peak was vast and varied, and there was an enormous trade network that ensured raw materials such as lead and marble made it to construction sites as far away as Britannia, or from there to Rome itself. Perhaps the officers on Hadrian’s wall missed their favourite garum produced in Hispania, or wine from their family’s Etrurian estate?

A Roman cargo ship, or ‘corbita’ (image: naval-encyclopedia.com)

To transport large amounts of goods where they needed to be at the farthest reaches of the empire, or to the heart of Rome, sea transport was the way to go, and massive ports such as those at Ostia, Carthage, Alexandria, and Piraeus were constantly alive with trade.

There were various types of ships, both commercial and military, but despite the efficiency of this mode of transport, it was even more restricted by the seasons and weather than travel over land. Sea travel could be absolutely treacherous, and the number of ancient shipwrecks that dot the coasts of the former Roman Empire are a testament to this.

The wreck of a 110-foot (35-meter) Roman ship, along with its cargo of 6,000 amphorae, discovered at a depth of around 60m (197 feet) off the coast of Kefalonia. (Photo: CNN)

If you want to read more about the various types of ships used in the Roman Empire, be sure to check out the Naval Encyclopedia page HERE.

As mentioned before, we often take travel for granted in the modern world, but it cannot be overstated how important travel was in the Roman Empire, nor how much Roman road and ship building opened up the world and the economy of Europe at the time. Yet another thing the Romans did for us!

Modern aerial view of the three harbours of the port of Piraeus, the port of Athens

We hope you’ve enjoyed this brief post about travel and transportation in the Roman Empire.

If you’re interested in taking a look, one particular tool that was especially useful when researching and writing An Altar of Indignities was Orbis: The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World. This special GIS tool uses ancient and modern source information to accurately create itineraries for travel between destinations in the Roman Empire, taking into account mode of transport, time of year, and whether travelling by land or sea. You can check that out HERE.

Part III – Roman Monuments of Athens

Pericles’ funeral oration for the dead of the Peloponnesian War in the Kerameikos of Athens by Philipp Foltz (1852)

When we think of Athens today, we inevitably think of that ‘Golden Age’ city which Pericles, after the destruction wrought by the war with Persia, helped to build into a beacon of light and learning for the world.

There is the ancient Agora with its restored stoa of Attalus, one of a few such structures, myriad statue bases and altars. There is, of course, the beautiful temple of Hephaestus overlooking the Agora where other temples of Ares, Apollo, and Aphrodite were located. This vast area was the beating heart of ‘Golden Age’ Athens.

There is the Kerameikos district about the great Dipylon Gate of Athens’ ancient walls where the road to Eleusis leads through the cemetery where Pericles gave his famous funeral oration honouring the dead of the Peloponnesian war.

On the south side of the Acropolis, there is the Pnyx where the citizens of Athens met to participate in the new experiment known as ‘Democracy’, as well as the magnificent theatre of Dionysus where the first dramas in history were performed, and the Odeon of Pericles beside the theatre where musical and poetry performances entranced Athenian audiences.

Painting of ‘Golden Age’ Athens by Leo von Klenze (1846)

Above all of these monuments and more was the temple of Athena Parthenos, the Parthenon, the crowning achievement of ancient Athens that hovered like Olympus above the city.

The remains of the ‘Golden Age’ of ancient Athens are everywhere, and history lovers flock to it as much today as they did in ages past.

However… Our story takes place in Roman Athens in the early third century C.E. What did Athens look like long after the setting of the city’s ‘Golden Age’? What did the Romans ever do for Athens?

The answer is, quite a lot.

Sadly, unlike many of Rome’s relationships, it started off with the usual violence that preceded the productive calm and beauty of the Pax Romana.

The Roman occupation of Greece really began in 146 B.C.E with the defeat and total destruction of the city of Corinth by Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus who arrived from the north, and then Consul Lucius Mummius.

Then, in 88 B.C.E when Athens and other cities revolted against Roman occupation, Lucius Cornelius Sulla devastated Greece. Athens suffered greatly at the hands of Sulla and much of that ‘Golden Age’ city was destroyed or damaged during his siege of the Acropolis.

Subsequently, Athens and the rest of Greece were to remain a part of the Roman Empire after the battle of Actium in 31 B.C.E when Octavian (later Emperor Augustus) crushed the forces of Mark Antony and Queen Cleopatra thus heralding the end of the Hellenistic Age and beginning the long period of Roman hegemony over the Mediterranean.

Emperor Augustus

After all the destruction, however, under Roman rule Athens began to experience a revival with several rulers really enriching the city for all that it had contributed. You see, many Romans, especially educated ones, really admired Athens and its legacy, a legacy from which Rome had adopted a great deal.

Under Roman rule, Athens saw the construction of several Roman monuments that still stand to this day, at least partially. We are going to take a brief look at a few of them.

Not only were improvements and repairs made to existing monuments, but completely new ones were added to his ancient city, including several public bath houses that were erected in various places.

Vintage engraving of the Theatre of Dionysus with the Roman scaena frons

Among the existing monuments that were repaired and updated was the ancient theatre of Dionysus where the great theatre festivals, such as the Dionysia, took place. At various stages over the Roman period, the theatre was renovated and expanded with more seating and a large scaena frons, or stagehouse.

Fifteen years or so after the Battle of Actium, a new odeon was built around 15 B.C.E in the middle of the Ancient Agora by the general, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. This covered, two-storey structure could seat about one thousand people and is still visible today by the carved tritons on its north side.

Recreation of the exterior and interior of the Odeon of Agrippa in the ancient Agora of Athens

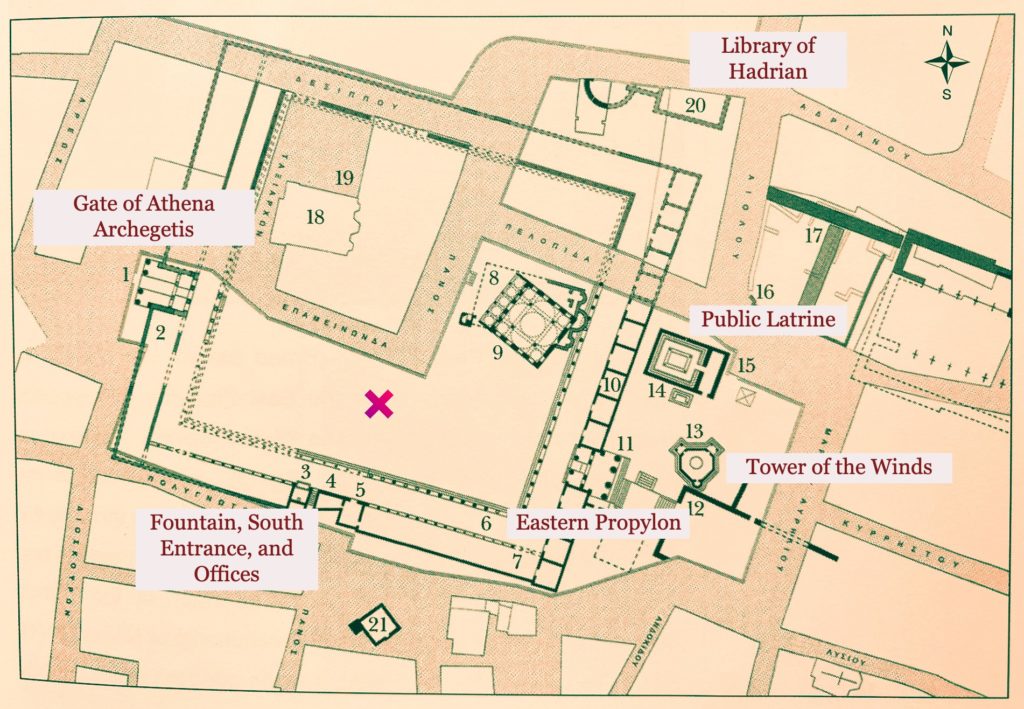

One of the most important additions made by Rome to the city of Athens was the Roman Agora or ‘Roman Forum’ built between 19-11 B.C.E by Augustus in fulfillment of a promise to the city by Julius Caesar.

This ‘new’ agora features largely in An Altar of Indignities, and is the site of a particularly riotous scene!

While the original ancient Agora of Athens remained an important focus of the city, it had become crowded with stoas, temples, and monuments to heroes and to the gods. There were fountains, a library, a mint, offices, altars, sanctuaries and more. But the first agora came to lack the great open space that allowed people to gather and trade with ease. The new, Roman Agora allowed for this.

Aerial photo of the Roman Agora of Athens with the gate of Athena Archegetis in the foreground

The Roman Agora of Athens consisted of a large paved, open-air courtyard that was surrounded by colonnades of white and grey marble from the surrounding mountains of Penteli and Hymettos. The colonnades were covered and had spaces for shops and merchants selling various goods, storerooms, the offices of the market, and a fountain. There was also an adjacent public latrine.

There were two propylaea, including the Gate of Athena Archegetis at the west end, and another propylon at the east end. Both entrances aligned with the ancient roads at either side.

The Tower of the Winds – the oldest meteorological station in the world

Just outside the eastern wall of the Roman Agora is a fascinating and unique Roman-era structure known as the Tower of the Winds.

The Tower of the Winds, built by Andronicus in the first century B.C.E, is said to be the oldest meteorological station in the world with sundials on the exterior, a hydraulic clock inside, and its bronze weather vane on top indicating the eight winds which is thought to have allowed merchants in the agora to know the winds and estimate the arrival of shipments coming from the port of Piraeus.

CLICK HERE to read our article on the Roman Agora of Athens and watch our full video tour of the archaeological site.

Emperor Hadrian (gold aureus)

There is one Roman ruler who looms very large in the history of Athens and that is Emperor Hadrian. Everywhere you go in the historic centre of the city, you are reminded of Hadrian. He loved Athens, and he loved to make things on an especially grand scale. Much of what he built in Athens is still visible today.

Beyond the walls of the Roman Agora are the remains of the great library built by Hadrian. Hadrian’s Library, as it is known, was built in 132 C.E. It was a large complex that served not only as a library, but also a cultural centre and public space that included lecture halls, a reading room, a vast courtyard and garden with a pool and, of course, the enormous bibliostasion where myriad precious scrolls were kept.

Today, you can visit the library by away of the monumental entrance near Monastiraki square, roam the gardens where mosaics are still open to the sky, and see the remaining walls of this magnificent piece off Athens’ cultural past.

The ‘Bibliostasion’ of the Library of Hadrian in Plaka, Athens

Southeast of the Acropolis are two more monuments to Hadrian’s generosity and love of grandeur. The one is the Arch of Hadrian which was built around 132 C.E. to honour the emperor. This gate, which one can walk up to today, marked the boundary between the ancient city of Athens and the new district built by Hadrian sometimes known as ‘Novae Athenae’ or ‘New Athens’.

Hadrian’s Gate

Just beyond the Arch of Hadrian, is perhaps one of the most impressive achievements of that emperor: the Temple of Olympian Zeus.

The Temple of Olympian Zeus, or the ‘Olympieion’ as it is known, was one of the largest temples ever built in the ancient world. Construction on it was begun as far back as the sixth century B.C.E under Peisistratos, but it was so ambitious that it was never finished.

Until Emperor Hadrian.

In 131 C.E., after over six hundred years, Emperor Hadrian finally completed the great Olympieion of Athens. The temple had a forest of 104 massive Corinthian columns and contained one of the largest cult statues of the ancient world.

The Temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens, as seen from the Acropolis

Today, only 15 of those magnificent columns remain standing. Nevertheless, this is a wonderful site to visit and the remains still give one a sense of the scale of this marvel of ancient architecture and great love that Emperor Hadrian had for Athens.

There is another Roman who features almost as largely as Hadrian in Athens’ past, and that is the wealthy Roman senator, Herodes Atticus. We will look at the man himself in a separate post in this series, but for now we will go over a few of the monuments he contributed to this ancient city.

The Panathenaic Stadium

The Panathenaic Stadium, or Kallimarmaro ( meaning ‘nice marble’), is one of the most recognizable monuments from ancient Athens, and it is still used to this day. It was originally built by Lycurgus in the fourth century B.C.E for the Panathenaea and is located in the small valley between the hills of Agras and Ardittos at the foot of the neighbourhood of Pangrati.

However, it was in about 144 C.E. that Herodes Atticus rebuilt the stadium in marble, after which it had a capacity of 50,000. This same stadium was excavated and restored in 1896 to host the first modern Olympic Games and is still used today for various Olympic ceremonies.

The Roman-era Odeon of Herodes Atticus, Athens

The monument for which Herodes Atticus is most famous in Athens is the one that bears his name: the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, or ‘The Herodeion’.

We will also take a close look at this amazing monument in a separate post in this blog series as it is central to the story of An Altar of Indignities. For now, the Odeon of Herodes Atticus was built around 161 C.E on the south slope of the Acropolis. It was a roofed odeon and served as a venue for concerts, theatrical performances and other public events. It remains in use to this day as a part of the annual Athens Epidaurus Festival, along with the great theatre of Epidaurus in the Peloponnese.

Philopappos Monument on the Hill of the Muses (Wikimedia Commons)

On the nearby Hill of the Muses, across the modern street from the Acropolis is another monument from the Roman period. It is known as the ‘Monument of Philopappos’. It was erected in around 114-116 C.E in honour of a Roman consul of Greek descent, Gaius Julius Antiochus Epiphanes Philopappos.

This grand monument that seems to jut out of the trees on the Hill of the Muses served as a mausoleum to this Roman-Greek consul, and is an indication of his importance to Athenian society at the time. Philopappos was said to have also been a poet and personal friend of Emperor Hadrian and Empress Vibia Sabina, making this yet another magnificent addition to the Hadrianic-period legacy of the city.

The Acropolis of Athens

When it comes to Athens, however, there is no monument greater, or more recognizable, than the Acropolis. This ‘high city’, crowned by the Temple of Athena Parthenos (the Parthenon) and other buildings and temples such as the Propylaea, the Erectheion, the Temple of Athena Nike, and the sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia, are all glorious reminders of Athens’ Archaic and Golden ages.

When it comes to the Roman period, much restoration of existing monuments was undertaken as structures had been damaged by time and war, not least Sulla’s siege of the Acropolis.

There were some monuments with statues that had been erected by foreign kings such as Attalos II of Pergamon (at the northwest corner of the Parthenon) and by Eumenes II in front of the Propylaea, the monumental entrance to the Acropolis plateau. These Hellenistic structures were later rededicated by Emperor Augustus and General Agrippa.

Recreation and present state of theT emple of Rome and Augustus on the Acropolis (Wikimedia Commons)

The only new, Roman addition to the Acropolis was that of the circular Temple of Rome and Augustus which was located about twenty-three meters from the Parthenon on the east side. This was constructed around 19 B.C.E to honour Rome and Emperor Augustus and was the last great construction to take place on the summit. This temple did not have a cella, as most temples did, but was more of an open air tholos (round temple) with a statue of Augustus beneath a roof supported by nine Ionic columns. Later, a metallic inscription was added to the temple to honour Emperor Nero, but this was later removed.

For a series of wonderful 3D recreations of Roman Athens, we highly recommend you visit the website for AncientAthens3D HERE.

Modern aerial view of the three harbours of the port of Piraeus, the port of Athens. The smaller harbours in the foreground are the ancient military harbours of Zea and Munichia. The commercial harbour of Kantharos is in the background.

Lastly, we cannot have a discussion of Roman monuments of Athens without mentioning the great port of Athens: Piraeus.

The port of Piraeus was made up of three harbours: the great commercial harbour of Kantharos (featured in An Altar of Indignities), and the smaller military harbours of Zea and Munichia.

Piraeus has been an important naval and commercial hub for centuries and, in the Classical Greek and Roman periods, it was vital. When Greece came under Roman rule, much was done to improve the port of Piraeus as the Romans relied heavily upon it.

Infrastructure, such as docking facilities, warehouses and the road to Athens, were repaired, improved and expanded. This was for efficiency, but also to accommodate the larger Roman ships. The Romans are also believed to have improved the fortifications of Piraeus.

Recreation of a Roman Quadrireme (From the Naval Encyclopedia)

The Romans certainly knew the strategic value of Piraeus as it became a major naval base for the Roman fleet in the eastern Mediterranean which was often engaged in combatting the rampant piracy that took place in the region. Of course, as trade was central to the workings of the empire, there were customs offices operated by Rome to carry out the taxation of goods.

There were also some religious additions made by Rome to Piraeus, such as shrines to Jupiter and Neptune, which blended in with the existing shrines and temples to traditional Greek deities whom the Romans also respected.

These changes and more are an indication of the continued importance of Piraeus to Rome as a strategic maritime hub.

While the remains of Athens’ Golden Age continue to be the most glorious to behold, it is undeniable that Rome – despite the destruction it initially wrought on the city – more than made up for it with the monuments its emperors and well-to-do citizens constructed.

Today, Athens is among the most beautiful cities in the world, dotted with ancient monuments that are still marvels to see.

That said, Roman Athens in the early third century C.E., when our story takes place, must have been a wonder, something to rival the halls of Olympus itself.

If the Gods had a home on earth, Roman Athens must have been it.

Artist impression of Roman Athens at its peak with the Ilissos River in the foreground and the Temple of Olympian Zeus centre-left.

Part IV – Food and Dining in Roman Society

Recreation of Roman foods

In the Roman Empire, diet, and the food that made up that diet, changed according to geographic region and the economic situation of the folk you are talking about. It wasn’t like today where we can just head down the street and buy a pineapple at any time of year. As a rule, there was no mass, global transportation of foods. Romans ate local for the most part, unless you were talking about wine, olive oil, olives and specialty items like garum. We’ll talk about those later.

First off, we need to dismiss the perception that Romans always ate elaborate meals with trays of songbirds, dormice, buckets of wine, and mountains of exotic fruits. This was not a usual occurrence, and when it did happen, it was usually the super-rich or the imperial family who ate like that, and then, only once in a while.

The truth is that the Roman diet was rather simple and, dare we say it, probably pretty healthy. Think Mediterranean diet.

Generally, the staples were various grains, often used in a sort of porridge known as puls, and breads made from a species of wheat known as frumentum. There was no such thing as pasta in ancient Rome! Panem et puls were the go-tos! Beans and lentils were also staples, and research has shown that these, rather than meat, were the breakfast of champions for gladiators!

To hear more about various types of grains from Pliny the Elder, CLICK HERE.

Fruits such as figs, grapes, and olives (yes, olives are technically, a fruit!) were eaten when available, as were a large variety of vegetables that made up the Roman diet. They did not have tomatoes or potatoes in ancient Rome, but they did eat a lot of cabbage, onions, garlic, parsnips, marrows, radishes, lettuce (not Caesar salad BTW!), asparagus, beets, and celery.

Mosaic depicting asparagus

When it came to meats, these were usually consumed as part of the main meal of the day, however that was not as likely or often for the poor. Sausages and domestic fowl were relatively common, as was pork, the latter being a special feature of certain festivals such as Saturnalia. Oysters and fish were very popular in ancient Rome, but there was the constant challenge of keeping them fresh when being delivered from the seaside to the city. It has been suggested that these were transported live, in barrels, to the places where they were to be consumed.

Needless to say, food poisoning may have been a common occurrence in ancient Rome, especially if one had a taste for oyster and other shell fish.

But let’s not think that there was nothing exotic on the Roman dining table. Well-to-do Romans would have consumed game such as venison or wild boar, snails and dormice (yes, little mice!) that were especially bred for the purpose of consumption, as well as small, wild birds or songbirds. If one attended a really fancy convivium, or banquet, one might even have had the chance to eat some peacock or swan.

Mosaic depicting typical Roman foods

With all of the foods mentioned above, I would be remiss if I did not make mention of the wide variety of fresh herbs and spices (too many to name here!) that Romans put on their food.

Romans liked their food highly spiced and cooked in sauces. Garum, a fermented fish sauce, was among the most popular. You can read more about garum by CLICKING HERE.

And there were desserts too! But these were not sweetened with sugar as we know it, but rather with honey. Romans, when they did have sweets, had a variety of cakes, pastries and tarts all sweetened with sticky goodness from the hive.

Lastly, what Roman shopping list would be complete without the two greatest liquid staples in the Empire? I am, of course, talking about wine and olive oil. These were both common in any household and came in varying qualities, depending on one’s income.

Amphorae that would have been used to transport and store wine and olive oil.

So how and where were all of these foods prepared?

Once again, this depended on the means of the household. Some kitchens were bigger than others, the same as today. In the case of tenement apartments in the Suburra, for instance, they did not have kitchens or cooking spaces which would have taken up much-needed space and been a severe fire-risk in the building.

In the case of tenement dwellers without kitchens of their own, there were communal ovens that were used, as well as plenty of food stalls where meals could be purchased – ancient Rome’s answer to take-out curry!

For those homes that did have kitchens (indoor or outdoor) the space often consisted of a round, or domed oven where a cook-fire was kindled with wood or charcoal. Cauldrons were also suspended over fires, as were frying pans or skillets.

Roman pans and skillets for cooking

When meat was cooked, it was more often boiled with a sauce, rather than roasted or grilled, although skewered roast meats were available, likely sold street-side.

I tell you, souvlaki has been around a long time!

Preservation of food was also important in ancient Rome, and so the curing and smoking of meats was common, as was the use of salt and pickling in vinegar for preservation.

What some archaeologists believe to be a sort of ancient souvlaki rack

Now we come to it, however, the nectar of the gods – wine!

Eight glasses of water a day?

Not in ancient Rome.

The most common drink in ancient Rome was wine. It was usually watered down, as it was considered barbaric to drink it undiluted, which is a shame if you ask me. But watered wine is not so bad. Go on, give it a try!

Just as with olive oil and garum, there were varying qualities of wines made at home and outside of the Italian peninsula.

Wine and bread? Yes please!

In addition to the fine Falernian and Chian vintages that might have graced the tables of the wealthy, there was also a wine concentrate that had to be diluted in water.

Among the poor, the drink of choice was posca, a sort of watered down acetum akin to wine vinegar. It might have had a bite, but perhaps it helped to keep one’s innards clean?

We prefer medieval Chianti Classico.

In Rome, beer and mead were not widely available and were much more common in the northern provinces.

And milk? Not so much. It was considered uncivilized to drink, the preferred use of dairy being to make cheeses, which were central to the Roman diet.

Fresco of a Roman dining scene

Now we’re going to take a brief look at the eating habits and formalities of dining in ancient Rome.

When it comes to eating, we seem to have inherited some of our modern-day habits from the Romans.

They normally ate one large, main meal a day, along with two smaller ones. However, the ientaculum, that is, breakfast, to the Romans, was not the most important meal of the day as we are sometimes told. In fact, Romans might have skipped this altogether before heading down to the Forum or visiting with clients or benefactors.

Breakfast in ancient Rome was light, and most likely involved puls, a sort of porridge, or some bread, perhaps dipped in honey or olive oil. They didn’t attack the day with a lumberjack breakfast in their stomachs!

In the early days, the midday meal or lunch, known as the cena, was the main, large meal of the day. This would perhaps have coincided with the sexta, the sixth hour of daylight, or siesta time of day. For more about the Roman siesta, CLICK HERE.

Lastly, the Romans would have enjoyed a lighter evening meal called the vesperna, perhaps involving bread and cheese, or some fruit.

Sensible eating for those early Romans!

Over time, however, the midday lunch became a lighter meal known as the prandium, and the cena, the main meal, was moved to the evening.

For the poor, most meals would have consisted of puls or bread, sometimes with some sort of meat, or vegetables if they were available. There was certainly less variety among the different meals of the day if one was not wealthy or at least well-off.

For the rich and well-to-do, things were different. As the cena was the large meal of the day it would have included three courses of food.

The first course was the gustatio or promulsis, and this would have involved appetizers of olives, eggs, raw vegetables, and simple fish or shell fish.

The second, or main course, the prima mensa, often included cooked vegetables and meats, the types and amounts varying greatly, depending on the occasion and wealth of the family or individual.

And lastly came the sweet course, the secunda mensa. This is when fruit and sweet pastries would have been served.

Fresco of eggs, wine, and songbirds. The makings of a cena, perhaps?

But what about the etiquette of dining? What was the etiquette? How did they sit? Did the Romans just move from course to course, gobbling up all that was placed before them?

Not exactly. In fact, there was a rigid system of seating, or placement. Contrary to modern views, most Romans ate while sitting, but when it came to the wealthy, they tended to recline on couches, especially at dinner parties.

At a banquet, or convivium, there would also have been entertainment between courses, perhaps by clowns, dancers, or readings by poets.

Food was eaten with fingers, and cut with knives. Spoons were also used, but forks were not.

Hypothetical triclinium visualisation (created by Martin Blazeby)

Today, when one attends a dinner, there are sometimes places assigned to guests. There might even be name cards, and some hosts might distance themselves from their least favourite guests at the table.

Well, this was also true in ancient Rome!

Imagine you’re invited to an evening cena at a senator’s home. You’re greeted in the atrium and led through the house to the dining room, the triclinium, just off of the peristyle garden. It’s dark out, and the scent of lemon blossoms and jasmine are on the night air. After a cup of watered wine, you’re shown into the triclinium by one of the well-dressed slaves who shows you to the couch known as the lectus medius, the middle couch of three, the couch of honour.

At this point, you’re very happy, for your host, seated with his wife on the lectus imus, the low couch, has honoured you above all other guests. The other guests behind you grin and bear it as they are shown to the high couch. From where you are, you have a wondrous view of the night garden and all of the other guests, and conversation comes easily, for you do not have to twist and turn.

Sound like a good evening? It could be. But the Romans took seating of this sort very seriously.

Horace (65 B.C. – 8 B.C.), in Satire VIII presents us with a scene depicting the seating arrangements and the trials of being a host in ancient Rome:

‘I was there at the head, and next to me Viscus

From Thurii, and below him Varius if I

Remember correctly: then Servilius Balatro

And Vibidius, Maecenas’ shadows, whom he brought

With him. Above our host was Nomentanus, below

Porcius, that jester, gulping whole cakes at a time:

Nomentanus was by to point out with his finger

Anything that escaped our attention: since the rest

Of the crew, that’s us I mean, were eating oysters,

Fish and fowl, hiding far different flavours than usual:

Soon obvious for instance when he offered me

Fillets of plaice and turbot cooked in ways new to me.

Then he taught me that sweet apples were red when picked

By the light of a waning moon. What difference that makes

You’d be better asking him. Then Vibidius said

To Balatro: “We’ll die unavenged if we don’t drink him

Bankrupt”, and called for larger glasses. Then the host’s face

Went white, fearing nothing so much as hard drinkers,

Who abuse each other too freely, while fiery wines

Dull the palate’s sensitivity. Vibidius

And Balatro were tipping whole jugs full of wine

Into goblets from Allifae, the rest followed suit,

Only the guests on the lowest couch sparing the drink.’

Horace (by Giacomo Di Chirico) Is he writing about the banquet he attended the night before?

Seems like Horace had a lot of fun with this, and his satires are certainly good for a laugh! We do feel for that host.

But what was all this ‘status seating’ about?

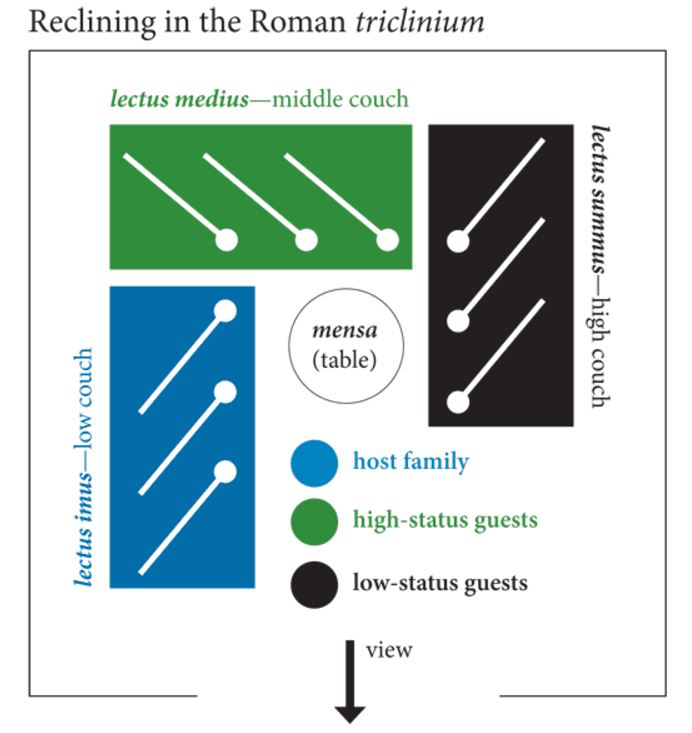

In a relatively well-off Roman household, three couches in a triclinium were standard. These were arranged around a low table, or mensa, and these couches had specific names and purposes.

The lectus medius, the middle couch, was the couch of honour, and was where important guests were placed. Because of its position, guests seated here were able to talk easily with other guests and had the best view, whether onto a peristyle garden or some sort of rural landscape.

The lectus imus, the low couch, was reserved for the hosts. It allowed them to speak with the high status guests on the lectus medius, and also the guests sitting directly across on the lectus summus.

Last and least, the lectus summus, or the high couch. This was not like the high table at a wedding today. No. The lectus summus in ancient Rome was the opposite. It was reserved for the lower status guests, maybe even for children if they were permitted to attend. This couch possessed less of a view, though still allowed its occupants the chance to participate in the conversation, though they might have had to turn awkwardly to do so. If you were shown to the lectus summus, then it seems you knew your place at the gathering.

If it was a rather large banquet, we can assume that the farther from the hosts and guest of honour you were on lectus summus side of the triclinium, the less important you were considered, or at least less influential.

Plan of typical Roman couch placement in a triclinium (from Reclining and Dining (and Drinking) in Ancient Rome by Shelby Brown; The Iris – Behind the Scenes at the Getty)

We hope you’ve enjoyed this article on food and dining in Roman society.

In researching this topic for An Altar of Indignities, and for other books such as Saturnalia: A Tale of Wickedness and Redemption in Ancient Rome, and Isle of the Blessed, we found that some of our modern perceptions about Roman banquets are indeed true, while others are clearly not. If one was eating in a tenement in the Suburra, you were not reclining on a couch eating grapes and drinking wine. It was a table and chair for you.

The food consumed, as well as the eating and dining habits of the poor and the rich were often separated by a wide gulf. Nevertheless, the wonderful colour and variety of the world of ancient Rome never ceases to delight!

Coming Soon!

Part V – The Roman Agora of Athens

Aerial photo of the Roman Agora of Athens with the gate of Athena Archegetis in the foreground

When one thinks of the great cities of the ancient world the first that most often comes to mind is Athens. It is a beacon of light, learning, and invention in the far-distant past that continues to inspire and influence us to this day.

It is also my second home, for I have been fortunate enough to return to Athens many times over the years to visit family, and to acquaint myself with the countless historical monuments that still stand, from the Parthenon and Kerameikos, to the often overlooked shrines along the Ilissos River which runs beneath the city streets.

When I find my way around the city of Athens, I do so by way of its ancient monuments. They have always been my guides, my markers for navigating the warren of streets and alleyways of the city of the Goddess Athena.

Athens, Greece – Monastiraki Square and ancient Acropolis with rainbow

But Athens is not just a place for those fascinated by mythological and Classical Greece. There is also a great deal for the most ardent of Romanophiles to see, for ancient Athens was loved and admired by a few Roman emperors, foremost among them being Hadrian (A.D. 117-138).

The Roman Agora of Athens is one of the main settings in An Altar of Indignities and, without spoiling any of the story, it is the site of a most riotous chapter.

Before we get into my visit to the site, we should talk a bit about its history and what there is to see…

Plan of the Roman Agora

The agora of an ancient Greek city was the central public gathering place. It was the political, social, business, athletic, and religious heart of the city. The agora was where anything of import happened or was decided.

And the city of Athens was, later in its history, fortunate enough to have two of them.

The first agora of Athens was, of course, the ancient one located at the northwest corner of the Acropolis and covering the area between it, the Areopagus, and the massive Dipylon Gate of the city. And the great route of the Panathenaic Way ran through it, all the way to the entrance to the Acropolis.

The ancient agora was filled stoas and temples and monuments to heroes and to the Gods. There were fountains, a library, a mint, offices, altars, sanctuaries and more. And in around 14 B.C., the Roman general, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa built an odeon in the middle of the ancient agora which had an auditorium for about one thousand spectators.

The Roman Agora from the eastern propylon

Just prior to the time that General Agrippa built his odeon, another building project began to take place in the city of Athens, this time sponsored by Emperor Augustus in fulfillment of a promise previously made by Gaius Julius Caesar. This new project was the Roman Agora, also known as the ‘Roman Forum’ of Athens. It was begun in 19 B.C. and finally finished in 11 B.C.

It is said that the reason for this new building project was because the ancient agora had become so full of monuments and buildings that there was no longer a wide open, public gathering place. As we shall see, the new Roman Agora would serve other purposes.

Gate of Athena Archegetis

The new agora, built by Caesar (posthumously) and Augustus, became the commercial centre of Roman Athens and the main oil market of the city. It was the beating heart of Roman Athens.

The monumental western entrance to the agora at the Gate of Athena Archegetis confirms who sponsored the building of the gate and agora with the following inscription:

The People of Athens from the donations offered by Gaius Julius Caesar the God and the Reverend Emperor son of God To Athena Archegetis, on behalf of the soldiers of Eukles from Marathon, who curated it on behalf of his father Herod and who was also an ambassador under the archon Nicias, son of Sarapion, from the demos of Athmonon

Of course, it was dedicated to Athena as the patron goddess of the city, and because it was Athena who had given Athens the olive tree, and hence the all-important olive oil which was sold in the agora.

The importance of the Roman agora as Athens’ main oil market during the Roman period is also reinforced by the inscription bearing Hadrian’s olive oil law on the doorway of the agora which outlined taxes and fines for false declarations of the production, export, or sale of olive oil there.

Atop the Gate of Athena Archegetis was an equestrian statue of Lucius Caesar, the grandson of Emperor Augustus.

The Roman Agora of Athens consisted of a large paved, open-air courtyard that was surrounded by colonnades of white and grey marble from the mountains of Penteli and Hymettos. The colonnades were covered and had spaces for shops and merchants selling various goods, storerooms, the offices of the market, and a fountain.

There were two propylaea, including the Gate of Athena Archegetis at the west end, and another propylon at the east end. Both entrances aligned with the ancient roads at either side.

The ‘South Colonnade’ with the remains of the fountains and agora offices on the left

Today, about a third of the north side of the Roman Agora lies beneath the modern streets and buildings, but the south colonnade remains largely intact. Remains, including inscriptions on columns, show that parts of the colonnade were set aside for specific merchants such as oil merchants or butchers. In some of the surviving stylobates, there are also round cavities of varying sizes in the marble that are supposed to have been used to measure out goods.

In the middle of the south colonnade, there was also a fountain with two cisterns at different levels. This was fed from springs on the north slope of the Acropolis just to the south. Also in this location were the market offices where citizens and merchants could pay taxes and take care of other business.

When there was heavy rain, the large court of the agora had an open air drain which allowed for runoff to be carried underground and diverted to the Eridanos River.

Tower of the Winds behind the eastern propylon of the agora

The Roman Agora today is, perhaps, most famous for what is known as the ‘Tower of the Winds’.

This octagonal structure, located just outside the eastern wall of the Roman Agora, contained the horologion built by the astronomer, Andronikos Kyrestes, in the mid 1st century B.C.

The Roman architect, Vitruvius, wrote about the tower in his work De Architectura…

…those who have inquired more diligently lay down that there are eight (winds): especially indeed Andronikos of Kyrrhos, who also, as an example, built at Athens an octagonal marble tower, and, on the several sides of the octagon, had representations of the winds carved to face their currents. And above that tower he caused to be made a marble upright, and above it he placed a bronze Triton holding a rod in his right hand. He so contrived that it was driven round by the wind, and always faced the current of air, and held the rod as indicator above the representation of the wind blowing.

(Vitruvius, De Architectura, c. 20s B.C.)

The Tower of the Winds is said to be the oldest meteorological station in the world with sundials on the exterior, a hydraulic clock inside, and its bronze weather vane on top indicating the eight winds which is thought to have allowed merchants in the agora to know the winds and estimate the arrival of shipments coming from the port of Piraeus.

Lastly, a few steps from the Tower of the Winds, also just outside the main precinct of the Roman Agora was a large public latrine, or vespasianae, with openings on four sides with a small court for ventilation.

The Roman Agora and the large precinct of the great Library of Hadrian beside it made this area the main administrative centre of the city of Athens, supplanting the classical agora in this role, especially after the Herulian invasion of Athens in A.D. 267.

Adam exploring the Roman Agora

As stated, this was not my first time visiting the Roman Agora of Athens. The site has also appeared in the #1 bestselling Eagles and Dragons series prequel novel, A Dragon Among the Eagles. However, each time I go, it is with a different purpose and perspective. This time, it was to research it as a setting for An Altar of Indignities.

We left our home in Pangrati early so as to try and beat the heat, and because archaeological sites were closing from 11 a.m. – 4 p.m. during the heatwave. Nevertheless, when we arrived it was a scorching 45 degrees Celsius with no intact colonnades to hide beneath as they would have had when the agora was whole.

After making our way through the crammed alleyways of Plaka and Monastiraki, we purchased our tickets at the office across the street and made our way in beside the Gate of Athena Archegetis.

Remains on-site

Once you enter, you are struck by the expanse of the open courtyard of the agora, even though a large portion of it is covered by the streets and buildings to your left. From there, you make your way along the remains of the south colonnade. Here, there are numerous column capitals, a sarcophagus, and other artifacts lying in the parched grass beneath palms where the resident cats and lizards doze and scurry.

As I walked, I could almost hear the crowds of the market around me, the sounds of the merchants selling their wares. I could imagine the tang of the olive oil in my nostrils. The marble courtyard must have been blinding in the midday sun, but one has to imagine that most of the shops would have closed by the sixth hour of daylight for the afternoon rest, as the Greeks and Romans were wont to do.

Site of fountain in the Roman Agora

We walked past the fountain and the remains of offices in the middle of the south colonnade and, at the end, found the carved hollows in the stylobate where merchants measured out (fairly, one hopes!) products such as grain or beans.

From there, the small forest of columns and a staircase indicate that you have reached the eastern propylon, the monumental entrance on the other side of the agora. As you walk up the stairs, you are keenly aware of the presence of what is the focal point of the archaeological site: The Tower of the Winds.

The Tower of the Winds – the oldest meteorological station in the world

The Tower of the Winds is a mesmerizing monument, as simple as it is. But one cannot take one’s eyes off of the images of the winds portrayed about the top. The smooth, white marble surface is beautiful, the lines of the sundials faintly visible.

One can imagine the citizens of ancient Athens walking up to it to check the time, the same as some do today with modern clock towers on some city halls. But this was the heart of Roman Athens, and so this meteorological monument was a fitting addition to this ancient gathering place.

Interior floor of the Tower of the Winds which held the mechanism of the water clock of the ‘horologion’

After exploring the area around the Tower of the Winds, including the vespasianae, the public latrine, we walked back across the open space of the great courtyard, taking time to pause.

I imagined this vast, ancient market place bustling with life, filled with people, with myriad things for sale, and the scenes of my novel that I was searching for began to take shape. I could see a beautiful comedic chaos unfolding!

For a writer of historical fiction, the city of Athens is a dream come true, for the bones of the ancient world are still there to see, to feel, and to inspire.

As the heat reached a literal fever pitch, I was finished with my research for the day and sought the nearest taverna for a cold drink in the shade, something which the Greeks and Romans would gladly have done at that time of day.

Thank you for reading.

Be sure to check out the video of our tour of The Roman Agora of Athens in order to experience this site for yourself. You can view it below, or visit the Eagles and Dragons Publishing YouTube channel by CLICKING HERE.

Part VI – The Hill of Ardittos and the Temple of Artemis Agrotera

In deciding to set An Altar of Indignities in Athens, I came to discover a history of the neighbourhood of Pangrati which I had not been aware of. Our family home is located in Pangrati, where I had been coming for over twenty-five years, and yet it was the research for this dramatic and romantic comedy of ancient Rome and Athens that helped me to truly discover its ancient past.

Pangrati is located on the lower slopes of Mount Hymettos, just the other side of the sacred Ilissos river which now runs from the shadow of the Temple of Olympian Zeus and then curves around beneath the modern streets of Ardittou and Vasileos Konstantinou. It is a neighbourhood of local families who have inhabited it for generations, and who now share their streets with artists and immigrants. The streets are lined with apartment blocks where people and drying laundry hang over the edges of run-down balconies watching the world go by and listening to the chorus coming from the weekly farmer’s markets, or laiki as they are called.

To me, however, beneath the grubby veneer of graffiti, trash, and construction dust, I can now see the rich and wondrous history of this ancient neighbourhood. And I don’t mean the beautiful curves of the massive Panathenaic stadium at Pangrati’s edge, first built by Lycurgus in 339 B.C.E, which we mentioned in Part III of this blog series.

Rather, I mean the mysterious hills of Agras and Ardittos that flank the stadium in the Ilissos river valley, particularly, the Hill of Ardittos, and the Temple of Artemis Agrotera beside it.

These are the two sites we will focus on.

The Panathenaic Stadium at the edge of Pangrati, with the Hill of Ardittos on the right

The hill of Ardittos in Athens lies directly beside the Panathenaic Stadium, to your right as you stand before the ancient athletic monument, between Archimidous and Arditou streets. It is about two-hundred and thirty-five meters high and can only really be accessed from behind the stadium at the entrance on Archimidous street.

The Hill of Ardittos is a small green oasis in the middle of the chaotic city, and it is often overlooked, despite its guarded stance beside the Panathenaic Stadium. Its pathways and slopes are dotted with massive agave plants and eucalyptus, cacti, pine, olive, almond, cypress and carob trees where crows – the birds of Apollo – keep a watchful eye.

Admittedly, I had walked by the hill many times over the years, simply noting its ancient slopes, the gnarled vegetation and the rocks protruding from beneath the soil. To be sure, the fence around it dissuaded me before, even as I walked by the hill on my way to the Temple of Olympian Zeus and the neighbourhood around the Acropolis, the Plaka.

Ardittos is a community park where locals jog, walk their dogs, workout, make-out, sneak a peek of paid events in the stadium, or just hold to a little peace at the heart of the city.

If you can find your way there through the steep and winding roads and pathways of Pangrati, you are rewarded with magnificent views of the stadium, the Acropolis, and the Olympeion, the Temple of Olympian Zeus.

View of the Acropolis from the Hill of Ardittos (photo source: ekathimerini.com – Irene Anastasiadis)

Apparently, Ardittos was named after a hero of ancient Athens named, Arditis. In ancient times, there were several sanctuaries in the vicinity, along the shores of the Ilissos, including sanctuaries of the Nine Muses, Pan, and Herakles.

But the Hill of Ardittos itself was also a religious and legal centre. It is believed that there were temples to Pan, Hecate, and Hera on or near the hill, but the remains that are visible today are thought to belong to the Temple of Tyche, the Goddess of Luck, who was a daughter of the Titans, Oceanus and Tethys.

Remains of the Temple of Tyche on the Hill of Ardittos (Wikimedia Commons)

Archaeologists and historians believe it possible that the Temple of Tyche on Ardittos was the site of offerings to Demeter and Persephone during the lesser Eleusinian Mysteries when piglets were offered, purified in the Ilissos River beforehand. There were also rites carried out here in honour of Dionysos during the festival of the Anthesteria.

There is no doubt that the Hill of Ardittos holds many mysteries, including a tradition that Herodes Atticus, that great Greco-Roman patron of the city, may even have been buried on it.

As I walk around Pangrati, a part of me doesn’t see the broken marble sidewalks or the apartment buildings that jut up to provide shade from the hot Athenian sun. Rather, I imagine and see the wooded lower slopes of Hymettos thick with pine and cypress, bees flitting about wild thyme, and boar crashing through the scrub while ancient Athenians made their offerings, or herded their goats and sheep on the mountainside.

It must have been beautiful and calm.

Artemis – The Huntress

According to legend, it was not only the Athenians who roamed the wooded slopes of Ardittos, Agras, and Hymettos.

This was also said to be the domain of Artemis Agrotera, the Huntress.

Just the other side of the Hill of Ardittos, there is another site that provides one of the settings for An Altar of Indignities, and that is the Temple of Artemis Agrotera.

Pausanias described the setting in the second century C.E:

The rivers that flow through Athenian territory are the Ilissos and its tributary the Eridanus, whose name is the same as that of the Celtic river. This Ilissos is the river by which Oreithyia was playing when, according to the story, she was carried off by the North Wind. With Oreithyia he lived in wedlock, and because of the tie between him and the Athenians he helped them by destroying most of the foreigners’ warships. The Athenians hold that the Ilissos is sacred to other deities as well, and on its bank is an altar of the Ilissian Muses. The place too is pointed out where the Peloponnesians killed Codrus, son of Melanthus and king of Athens.

Across the Ilissos is a district called Agrae and there is a temple of Artemis Agrotera (the Huntress). They say that Artemis first hunted here when she came from Delos, and for this reason the statue carries a bow. A marvel to the eyes, though not so impressive to hear of, is a race-course of white marble, the size of which can best be estimated from the fact that beginning in a crescent on the heights above the Ilissos it descends in two straight lines to the river bank. This was built by Herodes [Herodes Atticus], an Athenian, and the greater part of the Pentelic quarry was exhausted in its construction.

(Pausanias; Description of Greece, 1.19)

Antiquarian plate of facade of the Temple of Artemis Agrotera (by Stuart and Revett)

When we went in search of the Temple of Artemis Agrotera, it was on a hot Athenian morning when the temperature had already reached a blistering 45 degrees Celsius. Our path took us down the hill from Pangrati to the back of the Panathenaic Stadium, along Archimidous street, and then past the entrance to the Hill of Ardittos. We sweat our way up and down the steep side streets of the ancient district of Agrae until, arriving at Ardittou street, we found a lot where no apartment blocks stood.

We had arrived at the site of the Temple of Artemis Agrotera to find this:

Modern site of the Temple of Artemis Agrotera wit the Acropolis in the background

It was indeed a shock to behold this, but before we go any further, here is bit of history of the once-graceful temple that stood on this site…

The Temple of Artemis Agrotera was built between 435-430 B.C.E above the left or southern bank of the Ilissos river. But the temple was not only built here because this wood was thought to be the goddess’ first hunting ground.

Apparently, before the great Battle of Marathon in 490 B.C.E, when the Athenians crushed a more numerous invading Persian force, the Athenians made a vow to Artemis Agrotera – they were going on the hunt, after all! – that a goat would be sacrificed to her for every enemy killed in battle. The Athenians slew 6,400 Persian invaders.

Needless to say, the Athenians could not find enough goats to fulfill their vow to the goddess, but 500 goats were offered every year on the anniversary of the battle in early September.

For when the Persians and their followers came with a vast array to blot Athens out of existence, the Athenians dared, unaided, to withstand them, and won the victory. And while they had vowed to Artemis that for every man they might slay of the enemy they would sacrifice a goat to the goddess, they were unable to find goats enough; so they resolved to offer five hundred every year, and this sacrifice they are paying even to this day.

(Xenophon, Anabasis, 3.2)

Antiquarian plate of the plan of the Temple of Artemis Agrotera (by Stuart and Revett)

The temple to honour Artemis Agrotera, who had helped the Athenians, was built some years later by Callicrates, who also designed the Temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis, and for which it provided the precedent.

There were no precise, ancient descriptions of the temple of Artemis Agrotera. Thankfully, in the 1750s, two curious architects by the names of James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, went in search of the temple and recorded the details of what they saw, sketching what they could. Thanks to them, we know what the temple looked like.

Antiquarian plate of Temple of Artemis Agrotera architectural details (by Stuart and Revett)