Greetings Readers and History-Lovers!

Welcome to the final post in The World of Sincerity is a Goddess, the blog series in which we are taking a look at some of the research that went into our latest novel set in ancient Rome.

If you missed Part VIII on the theatre of Pompey, you can read that by CLICKING HERE.

In Part IX, we’re going to take a brief look at the ancient playwright whose work is central to the story of Sincerity is a Goddess: Plautus.

We hope you enjoy…

In misfortune if you cultivate a cheerful disposition you will reap the advantage of it.

– Plautus

Sincerity is a Goddess was always intended to be a comedy that involved the production of a play, but in the initial stages of research, one of the very first questions I had to pose myself was “What play?”

A lot hinged on the choice. Of course, when one thinks of ancient playwrights, one inevitably thinks of the great Greek playwrights, Aeschylus, Aristophanes, Euripides and others. But I knew that I wanted to use a Roman playwright’s work for this dramatic and romantic comedy, and so the choice inevitably came down to one between Terence and Plautus, the great comic playwrights of Republican Rome whose work was based on Greek New Comedy and subjects dealing with ordinary family life, love, and hilarity.

Terence’s plays are full of feeling. They are tender.

However, Plautus’ plays tended to be more comic and raucous with lots of music, songs, and duets that keep the audience at a distance. One might say that, in his time, Plautus had more popular appeal with the Roman people.

And so, I chose Plautus and his Menaechmi.

Titus Maccius Plautus (c. 254 – 184 B.C.)

Let deeds match words.

-Plautus

Who was Titus Maccius Plautus?

Let’s take a brief look at the man and his origins.

Plautus, who later became the great Roman comedy writer we know of, was originally from Sarsina, a town in northern Italy in Emilia-Romagna.

Early in his life, he moved to Rome where it is believed he worked at a trade in the theatre, either as a stage carpenter or scene-shifter. He also made money at some form of business, perhaps to do with shipping, but that business went under. He also worked as a baker, apparently.

The second century A.D. writer, Gellius, gives us some hints about Plautus’ life before fame:

Now there are in circulation under the name of Plautus about one hundred and thirty comedies; but that most learned of men Lucius Aelius thought that only twenty-five of them were his. However, there is no doubt that those which do not appear to have been written by Plautus but are attached to his name, were the work of poets of old but were revised and touched up by him, and that is why they savour of the Plautine style. Now Varro and several others have recorded that the Saturio, the Addictus, and a third comedy, the name of which I do not now recall, were written by Plautus in a bakery, when, after losing in trade all the money which he had earned in employments connected with the stage, he had returned penniless to Rome, and to earn a livelihood had hired himself out to a baker, to turn a mill, of the kind which is called a “push-mill.”

(Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights)

Luckily, his exposure to theatre is what got hold of him, and it seems that he began to write…and write…and write. We may not know much about Plautus’ personal life, but we are very fortunate indeed that much of his catalogue of plays survived the ages.

Plautine manuscript from 1530

Plautus wrote verse comedies, or fabulae palliatae which were based on Greek New Comedy, and he achieved huge success.

The plays of Plautus are the first substantial surviving written works in Latin and, no doubt thanks to the fact that they were so popular, they were copied frequently.

We know little about the man himself. Some hypothesized that even his name was not his true name and that ‘Maccius’ was actually a corruption of ‘Maccus’ the clown character in the Atellan farces, and that ‘Plautus’ meant ‘flat-foot’, referring to a character in the mimes. However, how many artists use stage names or pseudonyms? Lots, I’d say.

Though Plautus the man may be a mystery, we do know much about his extensive catalogue of works. It is not known exactly how many plays he wrote, but 21 have survived in their entirety, and there are fragments or mentions of an additional 30. In the quote above, Gellius alludes to many more as a possibility.

The metres of Plautus’ verse combined Greek metrical patterns with the stress patterns of the Latin language when spoken. But he went beyond simple translation.

Plautus adapted plays from Greek instead. He added much more music and songs, or cantica, like opera arias, then was normal in New Comedy. The performances were perhaps more like modern musicals which, in turn, partially owe their existence to Plautus’ work. Just think of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, by Stephen Sondheim. That musical is basically a great homage to Plautus!

Plautus’ plays appealed to Roman audiences because they presented a Latinized glimpse of Greek sophistication and outrageous behaviour that was outside of the audience’s experience. After all, theatre should be an escape!

Not by age but by capacity is wisdom acquired.

– Plautus

Plautus’ plays lacked the characterization and refinement of Greek New Comedy. His humour was more about jokes, verbal tricks, puns and alliteration that delighted the audience. He mastered the use of vulgarity, humour, and incongruity.

His stock characters were influenced by the Attelan farces, and included slaves, concubines, soldiers, and doddery old men. He created the ‘clever slave’ which would, in time, come to be known as a ‘Plautine Slave’. Often, the slave was smarter than his master, and even compared to a hero.

The plays involved everything from love and misunderstanding, to ghosts, rogues, tricksters, and braggarts who get humiliated in the end. Plautus only wrote one play based on myth, his Amphitruo. The rest of his plays portray the lives of more everyday people who his audiences could, more or less, relate to.

The Menaechmi itself is a comedy of errors about twins separated in infancy, in a Greek setting with numerous Roman references.

Not only did Plautus adapt Greek plays, he expanded on them and modified them in such a way that he made Greek theatre Roman!

Because he was a man of the people, having experienced their same toils, Plautus’ plays touched a nerve that made them extremely popular. They were performed for centuries after his death, well into the Renaissance, and his work was extremely influential on such greats as William Shakespeare (Comedy of Errors) and Moliere, who made use of many Plautine elements.

Like many comedians to this day, however, Plautus was not immune to criticism. Playwrights have always been rebels. The more conservative elements in Rome accused him of disrespecting the gods because his characters were sometimes compared to the gods either in mockery or praise. Sometimes, his characters even scorned the gods!

Some believe that Plautus was simply reflecting the changing tide of Roman society. He may have been controversial, but not enough to ban or prosecute him. Roman politicians were always keenly aware of the mood of the mob.

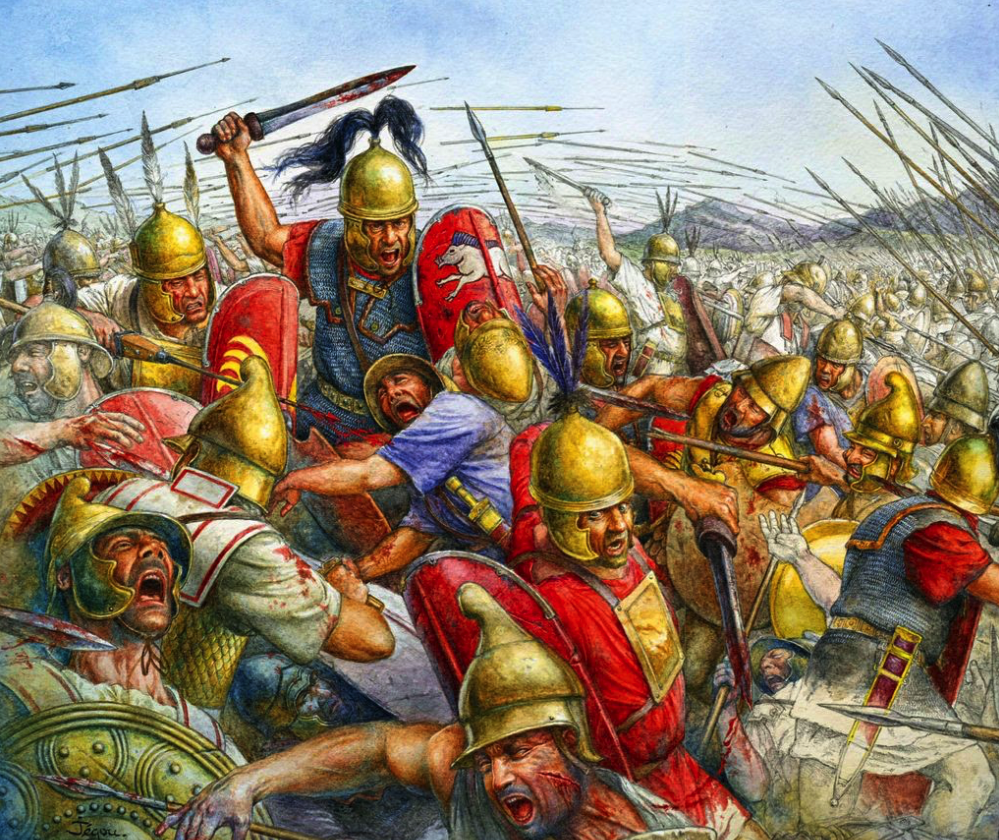

Artist impression of the Second Macedonian War

Conquered, we conquer.

-Plautus

War is a subject that seems constant throughout history. We are certainly aware of it today (sadly), as were Plautus and the Roman people.

During Plautus’ lifetime, the Roman people endured three great wars: the Second Punic War against Hannibal, and the First and Second Macedonian Wars against Philip V and Greece.

With the Second Punic War, the Roman Republic and people were fighting for their lives with the enemy being literally at their gates at one point. When it finally ended, they were exhausted by war, tired of it.

When certain powers in Rome wished to wage a successive war on Greece and Philip V of Macedon, the Roman people were not as supportive, and Plautus reflected these popular, anti-war sentiments in his plays such as Miles Gloriosus, and Stichus.

Many Romans did not want another war, and Plautus championed them in a way by giving voice to their anti-war voices and touching on themes of economic hardship forced on the citizens by the wars.

Sounds strangely familiar to us today, doesn’t it?

One could say that the greatest contribution of Plautus’ work, his genius even, was to take up the cause of the average Roman through comedy.

He was saying that the state should take care of its suffering people at home before undertaking military actions abroad.

We should bear in mind too that at this time in Roman history, when the Roman Republic was expanding and gathering power, Roman theatre was still in its infancy.

Plautus broke new ground in Rome. He made the people laugh, but he also gave them an important voice.

Since he has passed to the grave, for Plautus Comedy sorrows;

Now is the stage deserted; and Play, and Jesting, and Laughter,

Dirges, though written in numbers yet numberless, join in lamenting.

– Epitaph for Plautus, attributed to Plautus by Gellius and Varro

We have but scratched the surface of Plautus’ life and plays. Little more is known of him personally but, as with any writer, we can perhaps discern something of the man from the stories he put into the world.

There can be no doubt that the Roman world mourned his death on some level, as is attested by the moving epitaph shared by his fellow writers.

In a sense though, because so much of his work has survived time, and continues to be performed, to influence other art, Plautus is perhaps one of the most immortal of Romans.

Renaissance representation of Plautus

Hello Adam, Love this post about Plautius. Thank goodness some of his work was saved and, as you say we all need cheering up these days, so thankyou for sharing your well researched work. Hope all is well with you and family and you have managed to stay healthy and safe during these trying times of the pandemic. Have a wonderful weekend.

Cheers, Rita! Thrilled that you enjoyed this final instalment in The World of Sincerity is a Goddess! I’m actually kind of sad it’s done, but writing has begun on the next book, so cheerful days ahead! All is well here in Canada, if not a little cold and icy. Hope all is well on Crete! All the best! 🙂