Those of you who have read the books in the Eagles and Dragons series will know that they are set during the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus who waged a mostly successful war on Rome’s longstanding enemy, the Parthian Empire.

What you may not know, however, is that long before Severus, Verus, Trajan, and Mark Antony’s campaigns, there was a Roman who was the original punisher of the Parthians.

His name was Publius Ventidius Bassus.

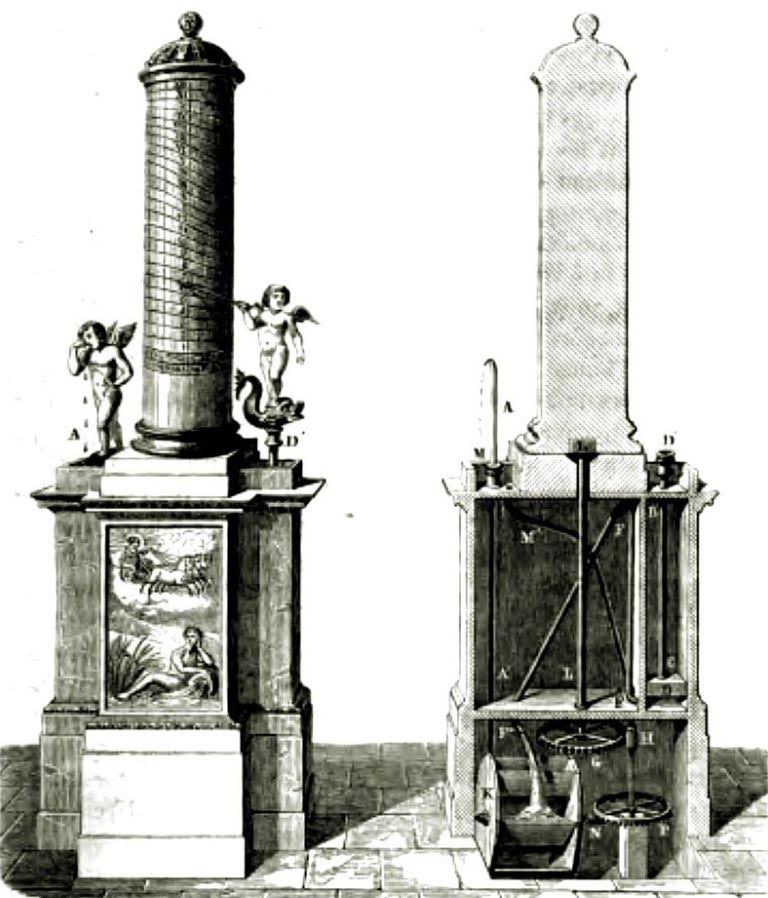

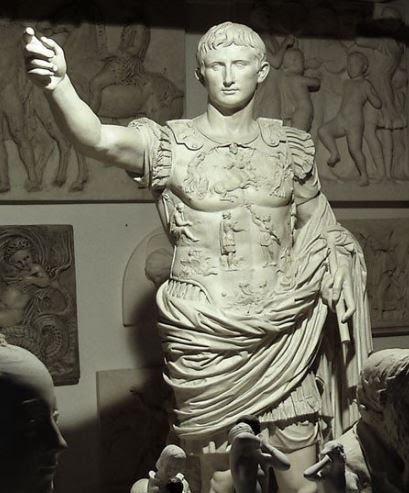

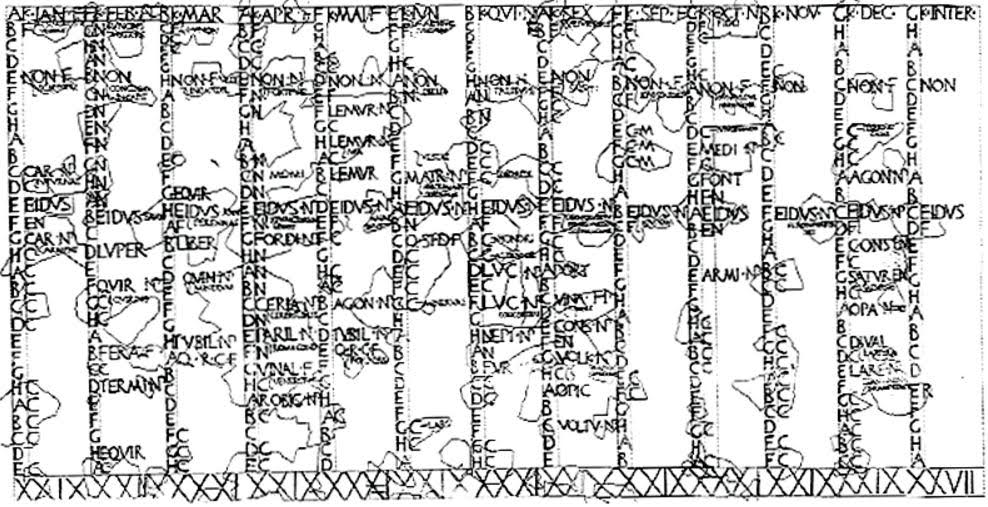

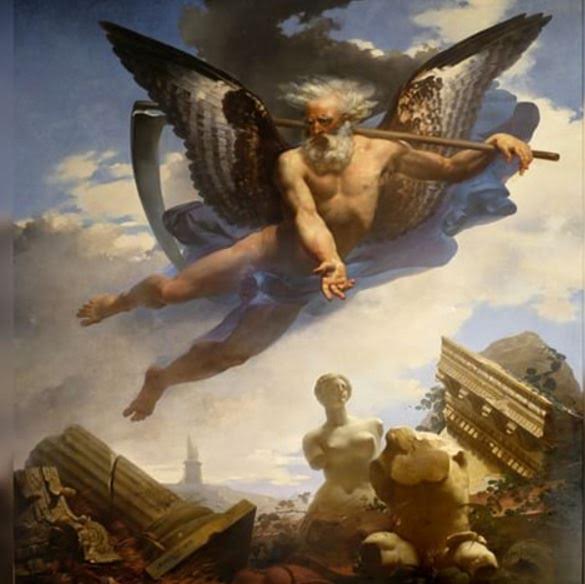

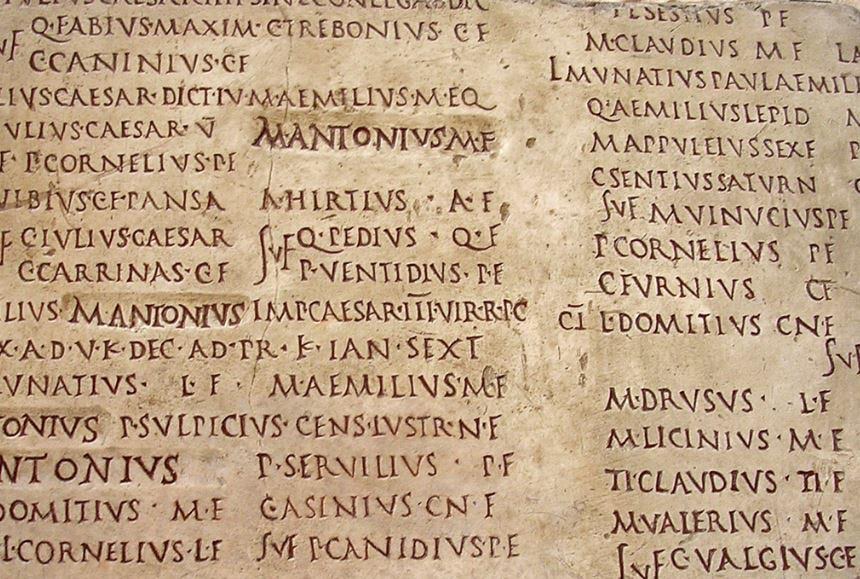

Denarius of Publius Ventidius Basso – minted during Triumvirate of Mark Antony, showing Jupiter on right holding a scepter and olive branch (Wikimedia Commons)

We all hear about the big names of history often enough, but once in a while, I like to highlight some of the secondary and tertiary characters who played a role in the history of the ancient world.

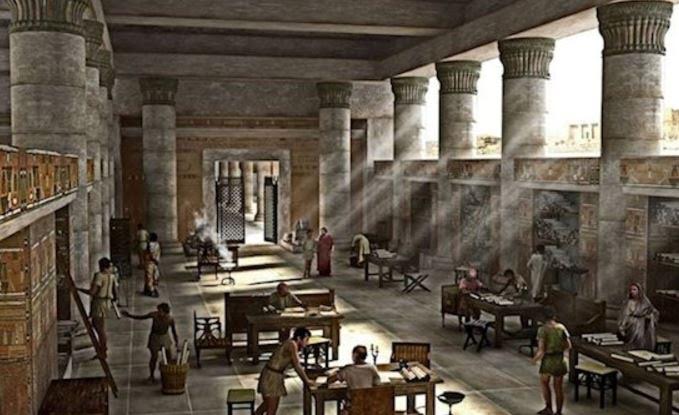

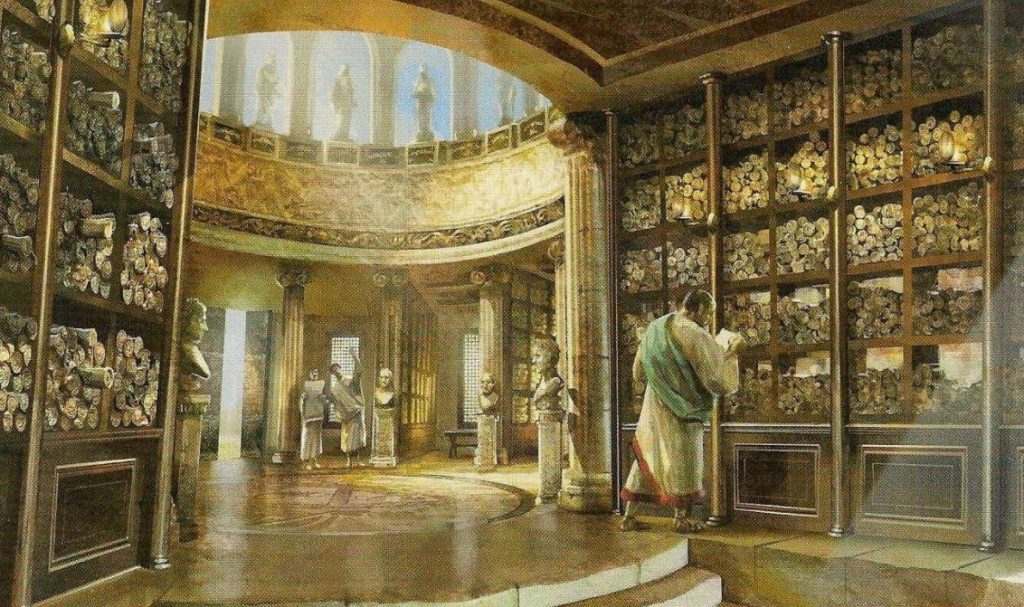

If you missed the previous post on Gaius Asinius Pollio, the founder of the first public library in ancient Rome, you can read that one by CLICKING HERE.

But today, we’re going to take a very brief look at Ventidius.

When I came across Ventidius I couldn’t help but admire his rise from very humble beginnings to the heights of glory on the battlefield for Rome.

He was not from Rome, but rather from Picenum, the birthplace of Pompey the Great, and located in what is now Abruzzo, to the East of Rome.

When the Social War of 91-88 B.C. broke out – this was the war between Rome and the Italian allies – the young Ventidius was in the eye of the storm.

After the Samnite Wars, Rome basically controlled the Italian allies, and the terms that were reached eventually led to great inequalities around money, land ownership, foreign policy, troop levies and more.

This left the Italian allies in poverty, despite their having contributed so many men to Rome’s legions.

In 91 B.C. the Tribune of the Plebs, Marcus Livius Drusus, proposed a series of fair reforms to remedy the situation with Rome’s allies, but for this he was assassinated.

When the Italian allies heard this, they declared independence and war broke out. Most of the Latin cities remained loyal to Rome, but a confederation of eight tribes joined forces (with their Roman-trained men) with the capital at Corfinium, in Abruzzo.

Ventidius and his mother were taken prisoner in the ensuing slaughter of that war and paraded through the streets of Rome in the subsequent triumph of the Roman general, Pompeius Strabo.

But Ventidius survived his ordeal, and as he grew up he became a skilled muleteer. Eventually, he joined the Roman army and after some time, came to the notice of Julius Caesar.

During Caesar’s Civil War, Ventidius acquitted himself admirably and came to be one of Caesar’s favourites.

After the assassination of Julius Caesar, Ventidius threw in his lot with Mark Antony who, after the creation of the Second Triumvirate, sent Ventidius to hold the Parthians back.

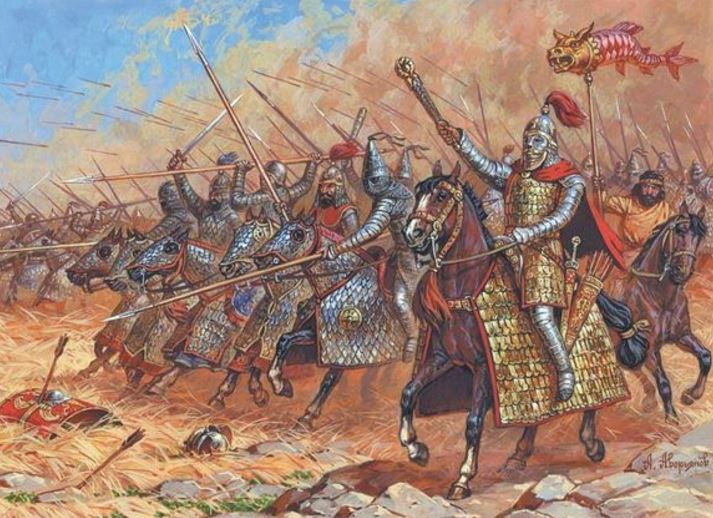

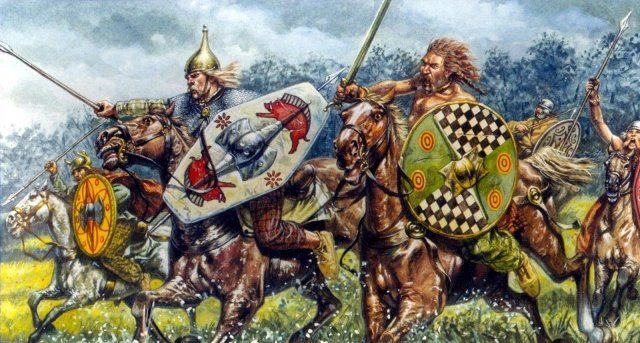

When the Parthians invaded Cilicia in 40 B.C., along with some Roman mercenaries led by Quintus Labienus, Ventidius went to meet them head-on with several legions of his own.

The muleteer from Picenum now had a large command!

Ventidius crushed the Parthian forces in two major battles: the Battle of the Cilician Gates, and a battle at the Amanus Pass.

Antony heard the news in Athens and celebrated:

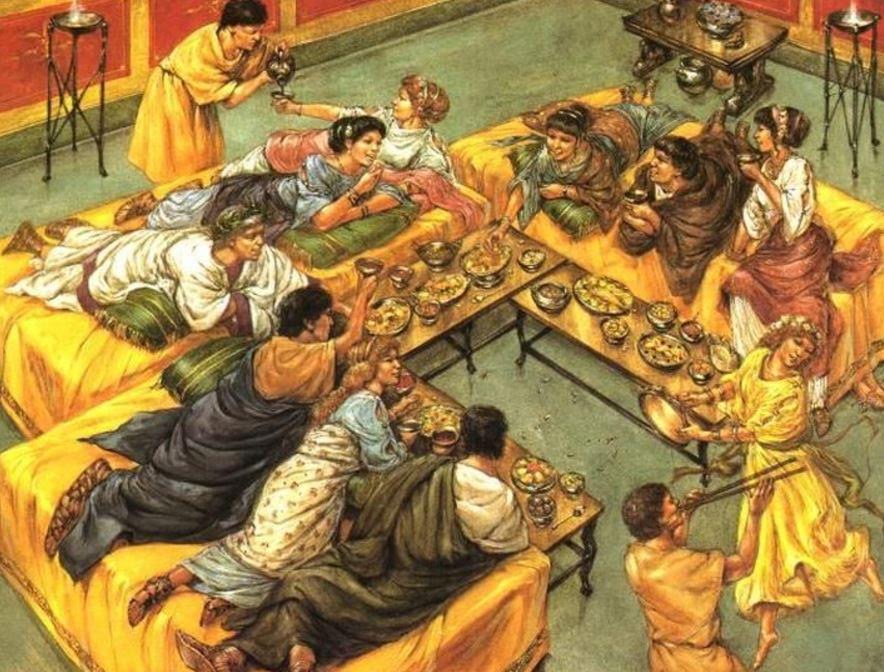

It was while he was spending the winter at Athens that word was brought to him of the first successes of Ventidius, who had conquered the Parthians in battle and slain Labienus, as well as Pharnapates, the most capable general of King Orodes. To celebrate this victory Antony feasted the Greeks, and acted as gymnasiarch for the Athenians. He left at home the insignia of his command, and went forth carrying the wands of a gymnasiarch, in a Greek robe and white shoes, and he would take the young combatants by the neck and part them. (Plutarch, The Life of Antony)

The Parthians were not to be deterred however. They proceeded to bring a massive force into Syria, this time led by Pacorus, the son of King Orodes.

Ventidius’ legions marched to meet the Parthians and utterly crushed them and slew Prince Pacorus at the battle of Cyrrhestica.

Because of Ventidius’ victory, the Parthians were held back in Media and Mesopotamia, and Rome attained a sort of vengeance for the horrible defeat of Marcus Licinius Crassus and his legions years before at the battle of Carrhae.

After the battle of Cyrrhestica, Ventidius pursued the Roman allies who had sided with the Parthians – mainly Antiochus of Commagene – and laid siege to them at a place called Samosata.

When Antiochus proposed to pay a thousand talents and obey the behests of Antony, Ventidius ordered him to send his proposal to Antony, who had now advanced into the neighbourhood, and would not permit Ventidius to make peace with Antiochus. He insisted that this one exploit at least should bear his own name, and that not all the successes should be due to Ventidius. But the siege was protracted, and the besieged, since they despaired of coming to terms, betook themselves to a vigorous defence. Antony could therefore accomplish nothing, and feeling ashamed and repentant, was glad to make peace with Antiochus on his payment of three hundred talents. After settling some trivial matters in Syria, he returned to Athens, and sent Ventidius home, with becoming honours, to enjoy his triumph. (Plutarch, The Life of Antony)

When I read this passage from Plutarch, I can’t help but shake my head at Antony’s jealousy of Ventidius.

It would obviously not do for Antony, who had always lived in the shadow of Julius Caesar, who was Triumvir of the East, to be outdone by a mere muleteer from Picenum.

But he was.

Publius Ventidius Bassus, a man who had worked his way up the ranks of the Roman army, had done what no Roman had done before, nor would do again for a long time.

He was the only Roman general (not an emperor) to celebrate a triumph for victory over the Parthians.

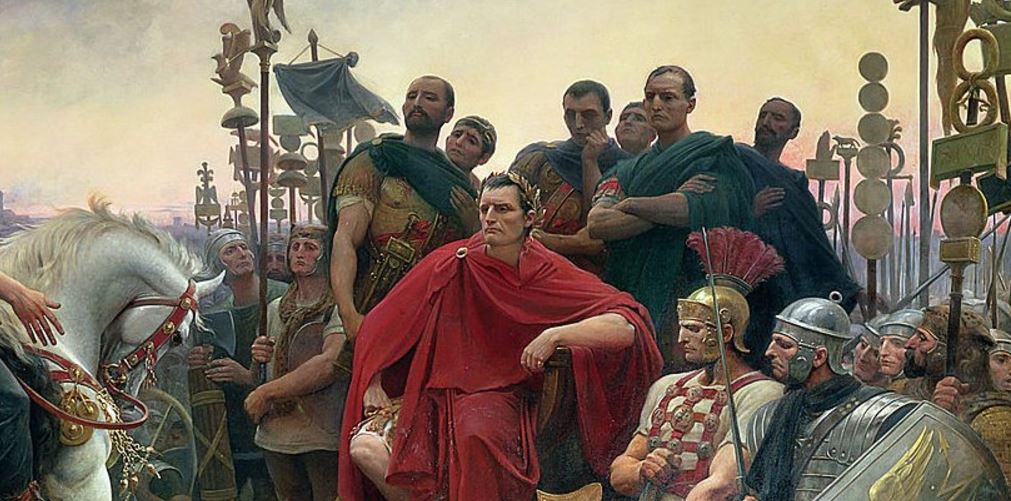

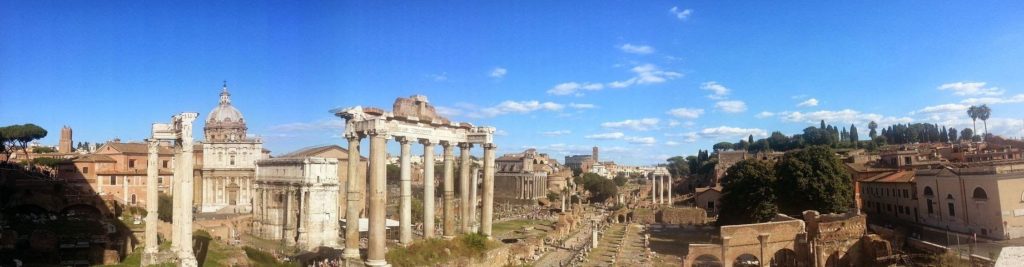

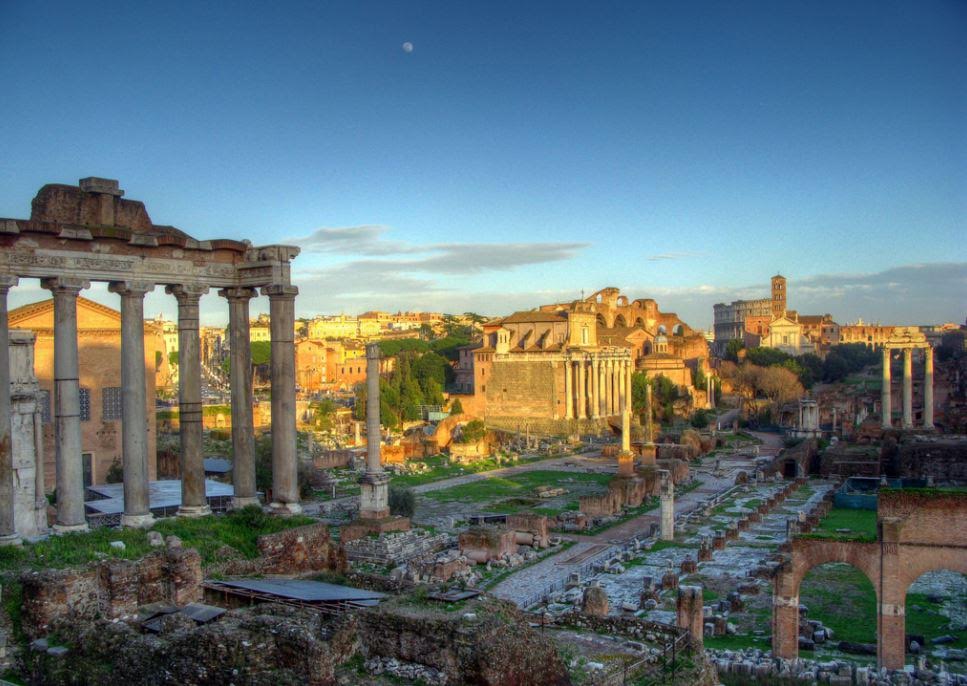

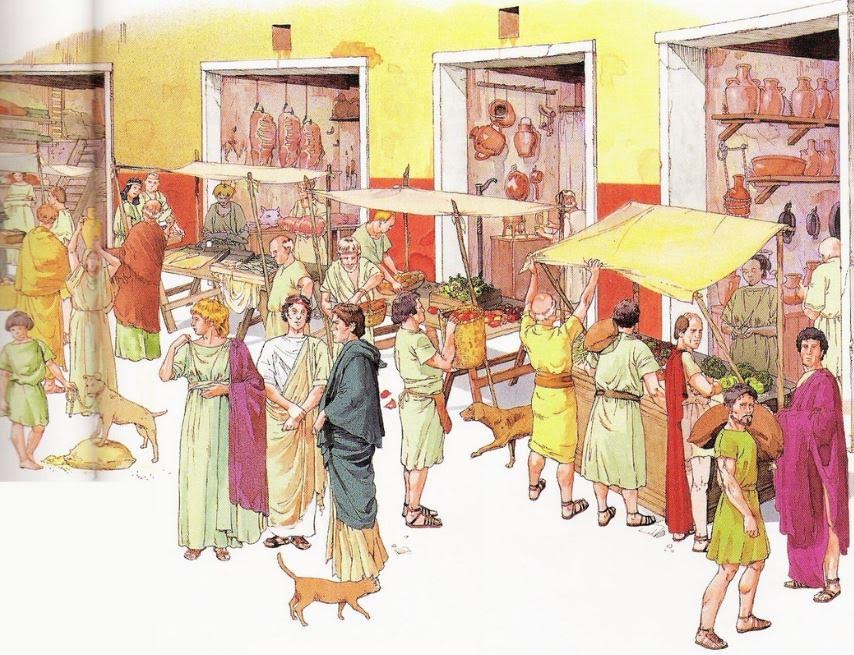

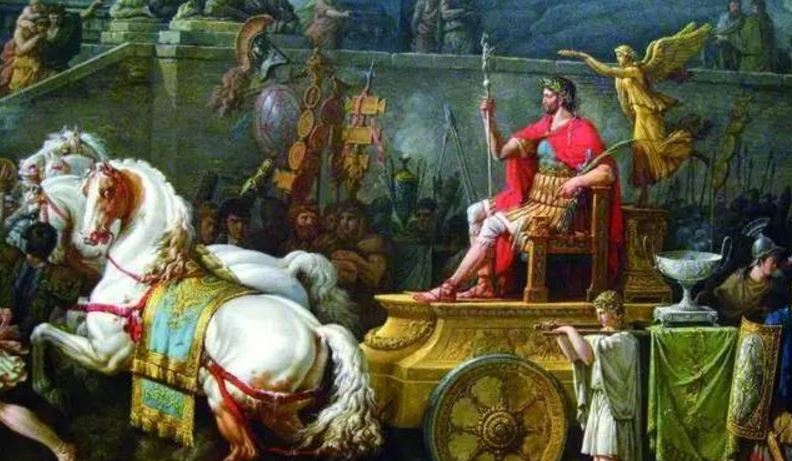

A Triumphal Procession – Ventidius would have celebrated in similar fashion back in Rome. The only general to be awarded a triumph for victory over the Parthians