Author: AdamAH

Hero of Rome: An Interview with Author Douglas Jackson

It’s always a thrill to stumble upon a new work of historical fiction that really meets your needs and expectations as a reader.

I’ve been working on my own books so much lately that I haven’t been taking the time I should to read in my chosen genre. Time is precious, of course, but as writers we need to remember to keep reading.

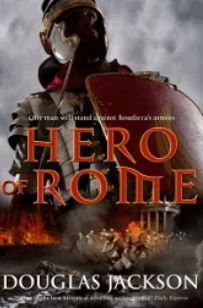

So, I went in search of a new series and found Douglas Jackson’s Gaius Valerius Verrens series.

I’ve just finished the first book, Hero of Rome, and what an adventure! I couldn’t put this book down.

The reader, writer, and historian in me was greatly impressed at how Douglas Jackson melded all the elements for a great read together. I decided right away that I wanted to interview the man behind the story.

Fortunately for us, he said yes!

So, sit back and enjoy hearing from Mr. Jackson about historical fiction and writing, inspiration, Roman Britain, and much more…

What got you interested in historical fiction in the first place? Was it a particular book?

History has always fascinated me, I’m a voracious reader and I always wanted to be a writer, so I suppose it was inevitable I’d end up either reading or writing historical fiction. My first HF love was Robert Louis Stevenson’s ‘Kidnapped’, which is a fantastic boy’s own adventure with sweeping landscapes and fascinating characters set on my own turf in Scotland. Looking back, the greatest influence would be George MacDonald Fraser’s ‘Flashman’ novels, which not only entertain brilliantly, but taught me more history than any of my teachers ever did.

Have you travelled to all the places you have written about? How important do you think travelling is for writing historical fiction?

I’d love to have travelled to the exotic places I’ve written about, but the twin constraints of time and money mean that I’ve had to use my imagination and Google Earth to create many of them. That said, I’ve been to Rome several times, Pompeii, Herculaneum and the Villa Oplontis, and it added hugely to my understanding of time and place. Likewise, a research trip to Colchester a few years ago gave me a feel for the landscape that enormously enhanced ‘Claudius” and ‘Hero of Rome’. I’ve just finished ‘Scourge of Rome’ which is set in Judaea, with the climax in Jerusalem, and it would have helped greatly if I’d been able to travel there and been able to appreciate the scale of the city, as it is I depended upon the above said Google and ancient maps and paintings I found on the internet. One place I’d really have liked to visit is the Cepha Gap, in a rather dangerous area of eastern Turkey, where I sited the entirely fictional battle that ends ‘Avenger of Rome’. It’s close to the fascinating city of Hasankeyf, home to archaeological treasures thousands of years old. The entire place is going to be drowned beneath an enormous dam that the Turkish government seems to be using to keep the local Kurds in their place.

When it comes to Roman Britain, which sites had the most influence on you, and why?

Over the years I’ve been to hundreds of Roman sites across the UK. Sometimes I can look at a town or a set of fields and tell by experience just about exactly where a Roman fort is sited because of the topography. Hadrian’s Wall, which is just down the road from the town where I grew up, is an obvious one. It has given me endless fascination, especially the discovery of the Vindolanda tablets, the slivers of wood shavings that have given us a unique insight into the way Roman auxiliaries on the frontier worked and lived, even played. But my greatest influence lies beneath a field just outside Melrose, in the Borders, where I lived for a few years. It’s a Roman fort called Trimontium and was, in turn, an outpost of the Wall, a staging post between the Hadrianic and Antonine Walls, and a legionary camping ground for at least two invasions of Scotland. The fort was excavated in 1911 by a local historian called James Curle. He was an amateur, but his excavations are regarded as a masterpiece of their time. He wrote a book called ‘A Roman Frontier Fort and Its People’, an astonishing record of his dig that is as intriguing as any novel. His finds were astonishing, including three cavalry parade masks (one of them iron, which is unique) and thousands of other Roman artefacts. I was fortunate enough to interview Curle’s niece and she had a host of fascinating stories about her uncle.

Your bio says you grew up in the Borders. How would you say the Borders differ from other areas in Britain? What sets them apart?

What makes the Borders different is its people. They’re a hardy breed, because history has made them that way: you have to be hardy to survive in country that was fought over by two nations for five hundred years like two dogs fighting over a bone. They also have a dry sense of humour that makes outsiders look at them strangely, but is hilarious if you take it the right way. What sets the area apart is that there’s no central focus. It’s made up of small towns set far enough apart to be completely different, but close enough to have a common purpose. They’re bitter rivals on the rugby pitch, but ask them who they are and they’ll tell you they’re proud to be a Borderer.

Boudicca is a larger-than-life character of history that many people have written about. What do you believe is the appeal of the queen of the Iceni to writers and readers alike?

Manda Scott, who wrote the Dreaming series, would be better placed to answer this one. I deliberately made Boudicca a peripheral character in ‘Hero of Rome’ because her story has been told so often and so well (see Ms Scott, above). Her obvious appeal is in the heroic myth that’s grown up around her as a great warrior queen who led men into battle and came close to pushing the Romans out of Britain. We’ll never know how much of it is truth. She probably owes her existence to a report sent to Rome by Suetonius Paulinus in the aftermath of the rebellion, which was later enhanced and embellished by a series of historians, including Cassius Dio, who’s not the most dependable record keeper. Paulinus, and the procurator Catus Decianus, brought the rebellion on themselves, and Paulinus may have painted a larger than life picture of his enemy in order to further his own reputation. The words that are supposed to have emerged from her mouth were written by Romans and I wish historians would remember that.

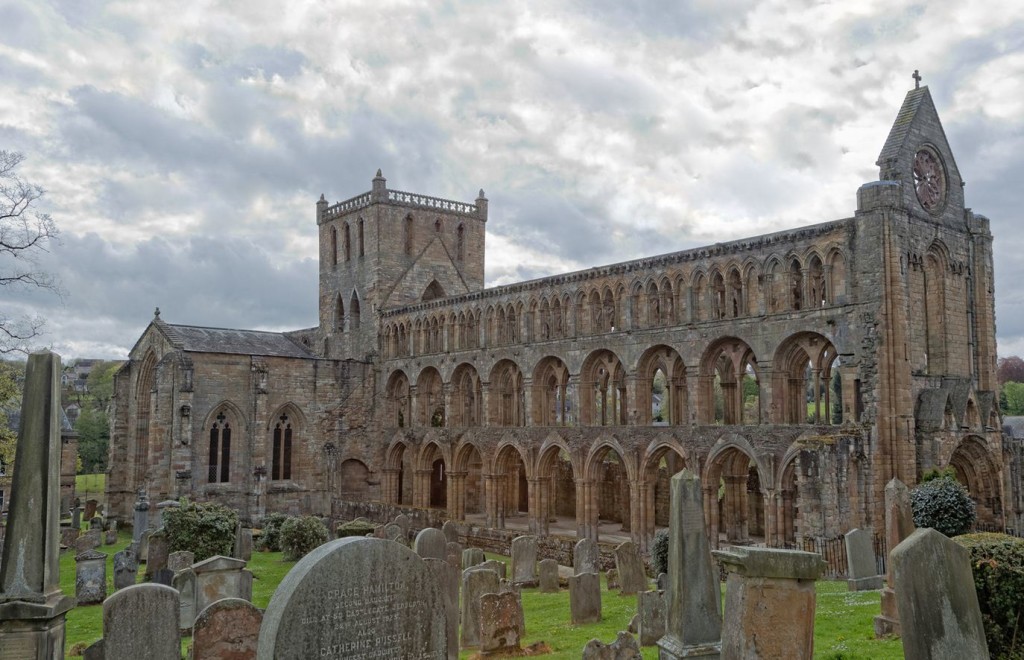

Where do you stand on the notion that a place has memory? Are there any experiences you would like to share about when a place really ‘spoke’ to you?

I think every place with a history has a memory if you’re patient enough to tune in to it. The first place I can remember ‘talking’ to me is Jedburgh Abbey in the town where I was born. The abbey was burned down five times by English raiding parties. It’s a magnificent 12th century building that soars above the town and I passed it on the way to school every day. You have to pay to get in now, but when I was a boy you were able to roam at will among the ruins. I can remember sitting there for hours just steeping myself in the mystique of the place and imagining what happened there. Folk must have thought I was mad.

What is your favourite historical fiction novel, and why?

‘Flashman and the Great Game’ by the above George Macdonald Fraser. Flashman is the adult version of the character in Tom Brown’s Schooldays, and he’s added coward, rogue, seducer and scoundrel to his original bullying repertoire. Yet Macdonald Fraser manages to make him curiously likeable as he relates tales of cutting and running his way to fame, glory and fortune with a sardonic wit. This is the story of Flashman ‘s incredible adventures during the Indian Mutiny as he blunders from heroic defence to massacre and mayhem and the final incredible climax which is as tense an ending as I’ve ever read in a book. Great stuff.

How has your experience as a reporter helped your novel writing? Has it ever hindered you in some way?

My 36 years as a reporter, sub-editor and editor have been an enormous help in my writing. I discovered I could write succinctly enough that I didn’t need a great deal of editing, that I could hold a 100,000 word story in my head as easily as I could a double page feature and that I could write fast and accurately. I’ve never missed a deadline. There’s no down side.

Most of your novels are set in the Roman Empire, but you have written some thrillers under the name of James Douglas. What made you want to change tack and write modern thrillers?

The need to make a living. I got into thrillers by mistake, but it’s refreshing to be able to kill someone with a gun for a change rather than a sword, and to live in a world where you don’t have to research every little detail as you walk down a street. I knew I had to write two books a year to make ends meet, so I pitched a second historical series to my editor. He liked it, but someone else had just sold Transworld a series set in the same period. Instead, he asked if I fancied trying a Dan Brown-type thriller. I said no, but he said ‘think about it’ and over the weekend I came up with three great ideas that I managed to turn into the first three Jamie Saintclair novels

You’ve also self-published a novel called War Games, which is the first Glen Savage Mystery. The publishing landscape has changed drastically in the last few years, and some would say there is no better time to be a writer. Tell us about the Glen Savage Mystery series and your indie-publishing experience thus far.

When I’d finished writing The Emperor’s Elephant, which became Caligula, Claudius, and through a curious metamorphosis, Hero of Rome, I knew it wasn’t good enough, but I didn’t know how to improve it. What to do? The answer was write another book. I had no idea whether I could make a success of historical fiction, so I thought I’d give a crime novel a try. Glen Savage appeared in my head one night and began speaking to me, to the extent that I got up and wrote down what he’d said. By mid-morning I had the novel mapped out and I knew it would be in the first person, with a sort of Sam Spade voiceover and the Borders countryside would be as much a character as Savage himself, in the same way James Lee Burke uses the Bayoux. War Games was actually the second Glen Savage book I wrote, the first, Brothers in Arms, focuses on his Falklands War experiences, but I haven’t had time to upload it yet. My self-publishing experience has been interesting, but ultimately disappointing. War Games got off to a reasonable start and had some great reviews, but it dropped into a black hole both in the UK and America. I always laugh when I see US writers on Twitter boasting about their hundreds of thousands of sales when they’re sitting at around the same Amazon rank I am and I know War Games is selling about four books a month. That said, excellent historical fiction writers like my pals Simon Turney and Gordon Doherty sell well enough to make a living from it, and I’d urge you to give them a try. I think the key is to have a series and build a following.

Many authors struggle for years to break out or get noticed. In hindsight, is there anything you would do differently? Do you have any advice for new historical fiction authors?

I was very fortunate, because I was picked up after just one rejection letter, so no, I wouldn’t do anything differently. One great help to me was the peer review website Youwriteon.com. You upload the first 10,000 words of your book and other writers critique it. It can be a pretty savage environment, but it teaches you to roll with the punches, which is vital further on down the line. I won a professional critique, the editor wanted to see the rest of the book, and the rest is history. My advice to any writer is to be prepared to promote yourself, because unless you’re already a name you’ll get very little help from your publisher. If you need a role model, look no further than Ben Kane of Spartacus, Hannibal and The Forgotten Legion fame. Ben works tirelessly to promote his books and those of other Roman HF writers. He’s also a great guy and deserves all the success he’s achieved.

Do you ever see your work being made into a movie? Who would play Gaius Valerius Verrens?

I think ‘Hero of Rome’ would make a great movie. It has everything. A likeable main character, an explosive start and a beautiful love story, all set around the background of the birth of Roman Britain, and of course an epic, bloody climax that makes the Alamo look like a Tupperware party. That bloke Ross, from Poldark, (UK TV star alert) who makes the ladies swoon would make a brilliant Valerius. Oddly enough I had word recently from a Hollywood film producer who’s talking to an international superstar next week about one of my Jamie Saintclair novels. It’ll make a great story when I can talk about it, and fingers crossed, but it’s like having a ticket in the lottery: just because you’ve got one doesn’t mean you’ll hit the jackpot.

Do you have any writing rituals that you would like to share? What is a typical ‘writing day’ like for you?

I get up in the morning, breakfast, sit in front of my computer and try to write 1000-1500 words in the morning, lunch, go for a walk, then the same in the afternoon. If I don’t hit my target I’ll write in the evening. I’m not much of a TV watcher and if I wasn’t writing I’d be reading anyway.

Is there a current writer whose work you are really enjoying at the moment?

I love John Le Carre’s work, because he makes it all appear so effortless. He’s managed to survive the end of the Cold War and make a new career for himself by the sheer power of his writing. I also thought CJ Sansom’s Lamentation was a brilliant return to form.

Is there a historic person in particular whose story you would like to tell in the future?

That’s actually a very difficult question. There are many stories it would be great to tell, but finding an era that no-one is writing about is almost impossible in such a crowded market. You have to find a combination of a great character and commercial appeal. I’m working on it!

What is your next project?

Jamie Saintclair is taking a rest, so I’m about 80,000 words into a Second World War crime novel called ‘Blood Roses’. It’s chock full of suspense, tension and moral dilemmas, and the hero faces a life or death decision on just about every page. It’s the first book I’ve written ‘on spec’ since The Emperor’s Elephant, which is both exciting and daunting, so if anyone in publishing thinks it sounds interesting, give me a shout. After that it’s back to Roman times. Valerius and Serpentius meet up in the dangerous gold fields of northern Spain, where Valerius is working for Pliny the Elder

I’d like to thank Douglas Jackson for taking the time to answer all of my questions.

If you have any questions or comments, be sure to leave them below.

It’s always fascinating to me to read about what inspires other authors, and hear about the places they’ve been. I’ve spent some time in the Scottish Borders myself, particularly at Trimontium, and I can tell you that it’s a wonderful site set in a beautiful landscape. If you ever get the chance to go, take it. You won’t regret it.

Luckily for those of us who love Roman historical fiction, there are many more books in the Gaius Valerius Verrens series, with more on the way.

Definitely check them out!

If you want to read about Mr. Jackson’s work, be sure to check out his website by clicking HERE or visiting Amazon. You can also connect with him on Facebook and Twitter.

As ever, thank you for reading…

Ancient Everyday – Mirror Mirror

I thought I would try a new series of blog posts looking briefly at everyday items in the ancient world.

Historical fiction is often about great battles, political events, and large-than-life characters.

However, one of the things that anchors these stories more firmly in the past are the everyday items that decorate the homes of the characters around whom the stories revolve, or the tools they use without a passing thought.

We might not notice these items ourselves, as readers, but trust me, if they were missing you would get the impression that the story was not quite authentic, or that it was lacking something you couldn’t put your finger on.

I was going through some photos I had taken the other day and saw this one of some Etruscan mirrors in the display cabinet at the Royal Ontario Museum.

Today, mirrors are things that we definitely take for granted, though I bet we all glance in them a few times a day.

The first mirrors were probably calm pools of water into which people could gaze at their reflections, or crude vessels filled with water. These are primitive, but they are still mirrors.

The earliest man-made mirrors appear to have been made of volcanic glass, or obsidian, and examples of these have been found in Anatolia which date to about 6000 B.C.

Polished copper mirrors have been found in Mesopotamia which date to about 4000 B.C., and some in Egypt which date to roughly 3000 B.C.

Dating to around 2000 B.C. there are examples of polished stone mirrors from Central and South America, and bronze mirrors from China dating to the same period.

During the ancient Greek and Roman period, polished bronze mirrors such as those pictured above seem to have been the norm, though these were not something that would have been possessed by the lower classes. Mirrors were probably more of a luxury item, especially the ornate ones. There is also mention of metal-coated mirrors, or glass mirrors backed with gold during the Roman period.

Mirrors such as these have been found among grave goods, indicating that they were, in some cases, prized possessions of the deceased.

When I see these more or less unassuming artifacts, it always makes me wonder who held this mirror, and what did they see, or think, or feel when they saw their own image staring back at them.

This is one of the things I love about archaeology and storytelling.

Every artifact has a human story behind it.

The King is Dead – The Passing of an Arthur

It’s always a sad thing to hear of the passing of an artist whose work has made a lasting impression.

It seems that every year more and more names shuffle off this mortal coil, leaving us with our own perceptions of their public face, but more so the faces of the roles they played.

This morning I found out that British actor Nigel Terry passed away at the age of 69.

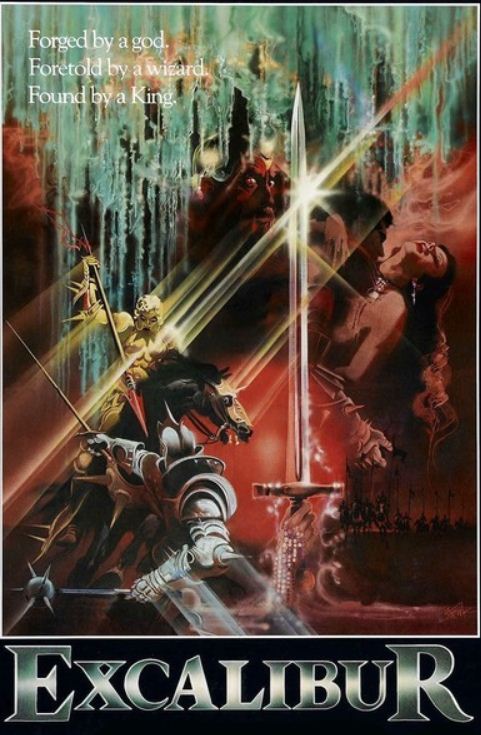

Many people might not know Nigel Terry at first mention. He was not necessarily a Titan of the big screen. However, he did appear in a few historical/fantasy dramas, most notably John Boorman’s 1981 film Excalibur.

I used to devour all things Arthurian, and it still is my favourite realm to visit, whether of history, literature, or archaeology.

Excalibur, based on Sir Thomas Malory’s Morte D’Arthur, will always be one of those movies that made a lasting impression upon me. The film brought to life the magic and mystery of the Arthurian legend like nothing else. It explored the nature of the king’s relationship to the land he is bound to protect, and took you on the quest with the Knights of the Round Table, from their courageous departure to find the Holy Grail, to depths of madness, despair, and pain, to the glorious attainment of the Grail, and the final confrontation at the Battle of Camlann.

Nigel Terry’s Arthur was of a different sort – naïve, daring, stern, trusting, brave, flawed, honourable. Whenever I imagine an historical Arthur in my head, it is often Nigel Terry’s face that appears.

If you have never seen the movie Excalibur, and you like Arthuriana, then you should definitely watch this movie. While you’re at it, see how many famous actors’ young faces you can spot in the cast about Nigel Terry.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y3cXcS49D64