Camelot by Gustave Dore

At the very south ende of the chirche of South-Cadbyri standith Camallate, sumtyme a famose toun or castelle… The people can tell nothing ther but that they have hard say that Arture much resorted to Camallate. (John Leland, Royal Antiquary, 1532)

Happy Holidays everyone!

Hard to believe we’re at the end of yet another year. How can so much happen in so little time? With time speeding by at such an alarming rate, History is, as ever, my anchor and touchstone.

This will likely be my last post of 2014. When I was trying to think of a suitable topic, it didn’t take me long to decide what better way to get into the holidays than a post about ‘Camelot’.

We haven’t been In Insula Avalonia since the springtime when I spoke about Glastonbury Abbey, and prior to that Gog and Magog, Wearyal Hill and the Holy Thorn, The Chalice Well, and Glastonbury Tor. If you missed those posts, you can read them on the old website. Just click on the names.

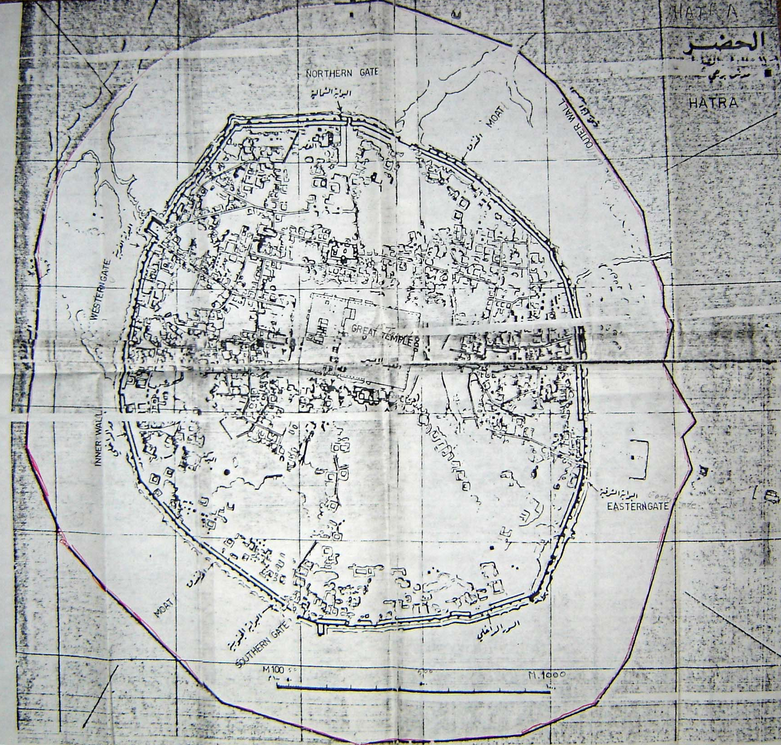

For Part VI of In Insula Avalonia, we’re going to look at a site that is just ten miles from Glastonbury itself: South Cadbury Castle.

The Knights of the Round Table (Edward Burne Jones)

Now, South Cadbury Castle, like so many of the other places that we have discussed in this blog series, is a site with strong Arthurian associations. As such, its importance and role is hotly debated.

Was South Cadbury Castle the power centre of the historical Romano-British warlord, or dux bellorum, we know as ‘King Arthur’? Was this the actual site of what has come to be known in the popular imagination as ‘Camelot’?

I’ve always been a strong proponent of the theory that there was in fact, an historical ‘Arthur’ who formed the factual basis for all the legends we love and cherish. So, when I look at sites such as South Cadbury, I do so with that in mind. However, that doesn’t mean that I accept a site’s association with Arthur on faith alone.

Arthur in battle beneath the Dragon banner

I know this site pretty well – as I studied it and wrote about it as part of my Master’s dissertation entitled Camelot: Comparing the historical, archaeological, and toponymic evidence for King Arthur’s Capital. As part of this, I looked at three of the main candidates for Camelot that had been put forward at the time – Wroxeter (Roman Viroconium), Roxburgh Castle (in the Scottish Borders), and South Cadbury. There is a copy of the dissertation hidden somewhere in the stacks at the St. Andrews University library in Scotland.

South Cadbury Castle is also where I cut my teeth as an archaeologist as part of the South Cadbury Environs Project team for a couple of seasons under the leadership of Professor Richard Tabor. This was a wonderful experience that helped me to get up close and personal with the site I had studied for so long – I dug test pits, got into bigger trenches in which curious cows came to watch what I was doing, carried out geophysical surveys with a magnetometer, and found some curious objects such as a bronze dolphin that formed the handle of a Roman drinking cup.

An archaeologist carries out geophysical survey at Sigwells with Cadbury Castle in the back left

Most of all, I was given the chance to spend more time on this amazing, and yes, magical, landscape.

Before I give my thoughts on wandering the slopes of South Cadbury Castle, we should have a look at what it actually is.

South Cadbury Castle is not the late medieval castle with banners flying from tall towers that make up our usual image of Camelot. It is a 500 foot high Iron Age hill fort located in the pre-Roman era lands of the Durotriges. Occupation of the site began in the Neolithic period and it went through various stages of occupation from the 5th century B.C. onward.

Camelot as portrayed in the movie First Knight

By the time of the Roman invasion of Britain, it had four massive defensive ramparts with an inner area of about 18 acres. Access to the top was by two entrances, one to the north-east and the other, larger one to the south-west. The Iron Age occupation of the site came to a violent end around A.D. 43 when Vespasian stormed the southern hill forts of Britannia.

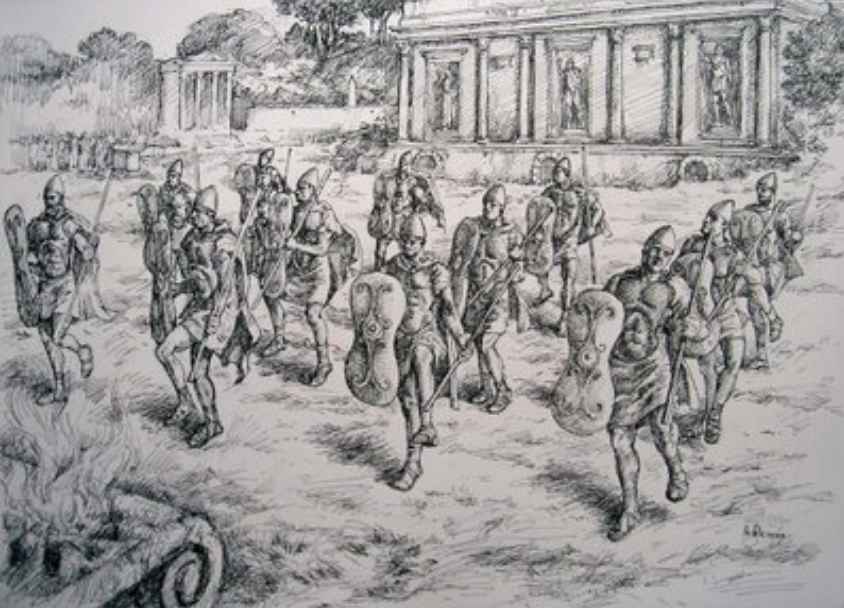

British Belgic Warriors of the Iron Age – Illustrated by Angus McBride (source – Rome’s Enemies 2 – Gallic and British Celts)

The Romans made little use of the site, though there have been some theories that it was used as a Roman supply station.

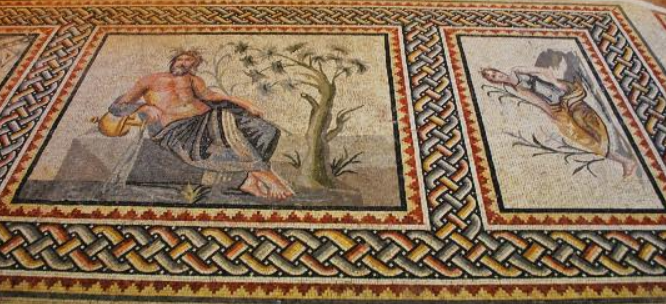

In the 3rd and 4th centuries, there was renewed activity with visits being made to a Romano-Celtic temple that was built on the site. During excavations, a bronze letter ‘A’ was found that some believe belonged to this temple, which was perhaps dedicated to Mars, or some other deity.

However, when it comes to South Cadbury Castle, the period that I am concerned with is the 5th and 6th centuries A.D. This period is known as the ‘Arthurian’ period, and it is at this time, after Rome’s legions have left the island, that the archaeology shows a massive refortification of the hill fort.

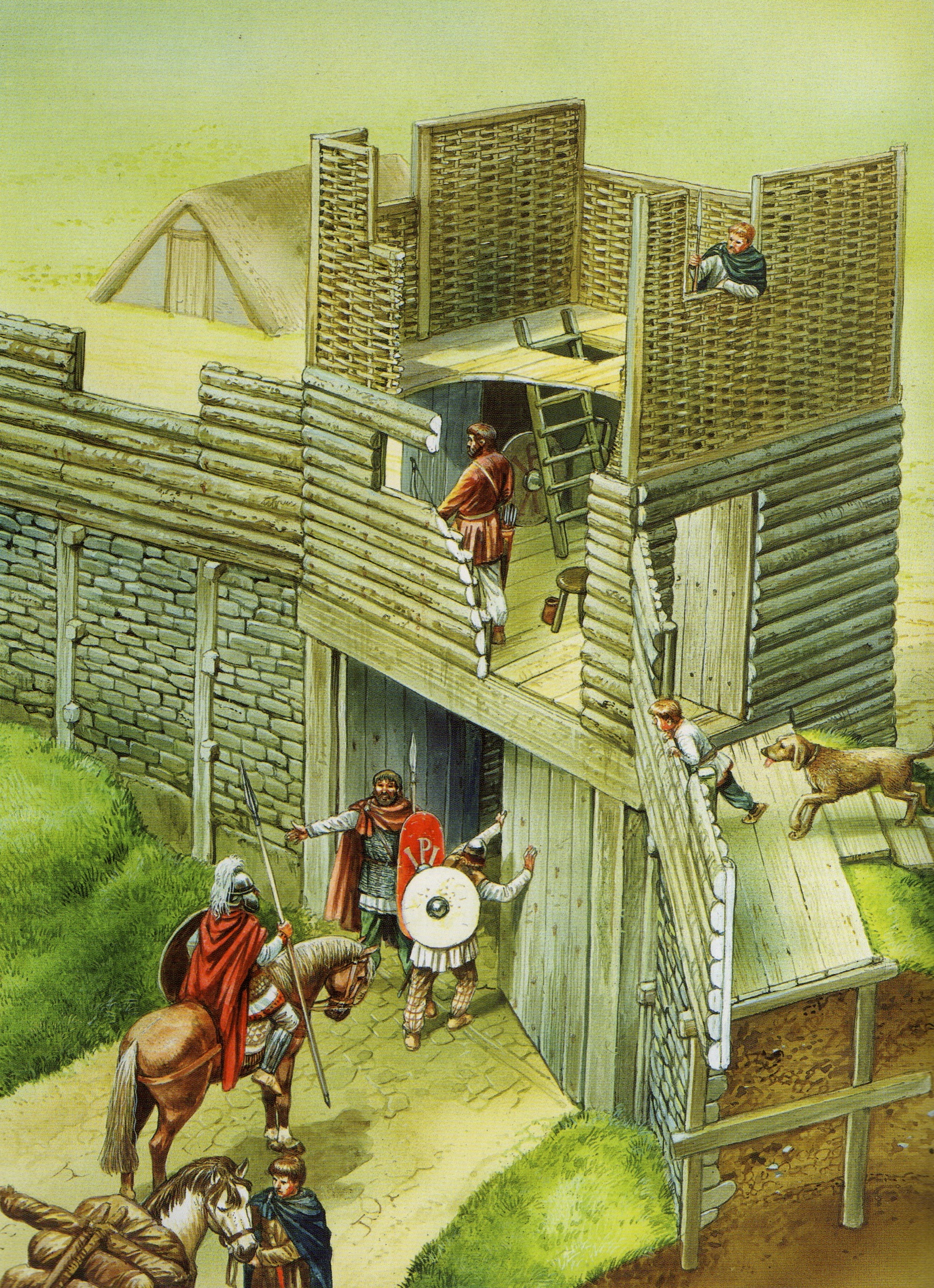

Artist Reconstruction of South Cadbury Hill Fort – Illustrated by Peter Dennis (Source- British Forts in the Age of Arthur)

Though it is much debated, South Cadbury’s association with the Arthurian period stems not just from hearsay and folklore. It has the archaeological evidence to back it up.

There have been a few big excavations of the hill fort over the years, but the biggest of all took place in the late 1960s and was headed by Professor Leslie Alcock. Professor Alcock and his team discovered evidence for a large scale occupation and refortification of the hill fort, during the Arthurian period, which showed repaired defences, including a strong gatehouse at the south-west entrance, and most importantly, several buildings, including a kitchen and a large timber hall on the fort’s high plateau.

South Cadbury Timber Hall

The discovery of post holes reveals a finely-built timber hall that was on a large scale, measuring about 63×34 feet. This hall would not have been the great castle hall of late medieval romance, but rather something like the timber drinking halls of the period, more like to the Golden Hall of Meduseld, the seat of King Theoden in Lord of the Rings.

Another very telling discovery at Cadbury Castle was the large quantity of Mediterranean pottery that dates to the Arthurian period of occupation. This is the same pottery type that was discovered at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall, a site that also has strong Arthurian associations. One might think that shards of pottery from wine, olives and olive oil might be pretty mundane, but they anchor the sites strongly in the period, and also show that someone of importance was associated with the site. Not everyone could afford to import such things through trade.

6th Century British Warriors – Illustrated by Agnus McBride (source – Arthur and the Anglo-Saxon Wars)

The refortification of the hill fort during the Arthurian period was on a massive scale, and would have required many resources and men to hold it. South Cadbury castle was, in a way, on the front lines of the British struggle against the invading Saxons, and would have been well-placed to meet the Saxons as they advanced westward.

Based on the refortification, and evidence of the gatehouse that linked the ramparts running over the cobbled road at the south-west corner, this place was likely the base for an army that was large by the standards of the period. It may way have been the site of the court of the dux bellorum, or the historical Arthur.

Artist Reconstruction of the South-west gate – Illustrated by Peter Dennis (Source – British Forts in the Age of Arthur)

I am only scratching the surface here, as far as the archaeological finds. At a later date, I will do a more ‘academic’ post on the archaeology of South Cadbury Castle. It truly is a fascinating site that was finally abandoned in the early 11th century when it was being used as a royal mint during the reign of the Saxon king, Aethelred.

Today, South Cadbury Castle is a quiet hill in the midst of the Somerset countryside where it lies just south of the A303 motorway. The levels of its steep ring fortifications are now overgrown with trees and scrub, and cows roam the fields surrounding it.

South Cadbury from the North

When you visit, you pull your car into the small car park at the south end of the village of South Cadbury, just east of the hill fort. From the lane, you can’t really tell what you’re looking at. It seems like a steep, forested hill with a path leading up.

This path leads up to the north-east gate of the hill fort, and for me, it was always the gateway to another time, another realm.

Path Leading to the North East Gate

It’s difficult to approach this site and reconcile the archaeologist/historian side of me with the romantic. Arthurian lore runs deep in my veins, it has a hold on my psyche since I was very young. The first time I visited the site, I could almost hear the call of clear trumpets and the thumping of horses’ hooves upon the ground as knights returned home from their adventures, their horses brightly caparisoned, their armour shining brightly in the light of the Summer Country.

Of course, I know that is not how it was during the Arthurian period, but this is a place and story that fires the imagination. Cadbury Castle’s associations with Arthur include a hollow hill where he sleeps until he is needed again, the site of ‘Arthur’s Well’, a lane on the slopes where his horse drank when he led the Wild Hunt, and of course the location of Camelot.

To me, however, the idea of South Cadbury as the main fortress of a Romano-British warlord leading a group of skilled cavalry in a last stand against the invading Saxons is no less romantic.

Northern Rampart of South Cadbury Castle

During my subsequent visits, I would ascend the dirt and rock path leading up to the north-east gate and pause with reverence for the history of the place. I would imagine looking ahead, up the slope to the central plateau of the hill fort to the great wooden hall where smoke from the hearth of Arthur’s hall wafted into the sky as he and his warriors discussed the fight for their lives and their Romano-British heritage.

The warriors that manned the ramparts of South Cadbury, who dined in the hall, and who rode out to meet the Saxons have been wrapped in the fabric of myth, as much as the Isle of Avalon not ten miles distant. But they certainly left a mark on the place, on history and folklore.

As I walk the grass-covered ramparts of South Cadbury, watching the crows dive in the winds above the steep slopes, I can’t help but wonder if Arthur, Gawain, Bors, Tristan, Bedwyr, Cai and others walked that same path, a wary eye out for a sign of the enemy that would shatter the peace they had fought so hard for at Mons Badonicus.

Rarely have I felt so at peace and nostalgic as I have when walking around this hill fort. I can still smell the damp grass and fell the sun on my face. In my mind, I still watch the puffs of white cloud blowing over the Somerset landscape as I pause to gaze to the north-west and see Glastonbury Tor rising out of the earth.

Glastonbury Tor from South Cadbury

In ages past, when the levels flooded, the distance between Cadbury Castle and Glastonbury might have been crossed by boat if you knew the way and which rivers to take. Indeed, one of the discoveries found around the hill fort was a boat.

South Cadbury Castle is, in some ways, closely tied to Avalon, and you can feel that as you look from the top of one to the other.

After making a round of the ramparts, and standing on the roadway of the south-west gate, I would always spend a good amount of time on the plateau, watching the sky and letting my imagination take hold.

Plateau of South Cadbury where the timber hall was located

The beauty of visiting a site, rather than looking at in a book or online, is that direct connection with the past, with the history of the place.

Yes, many of the stories we know and love about Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table are medieval fabrications. But I do believe that every legend has its base in fact, and so it’s a comfort to know that the layers of myth and legend are veined with elements of truth and history.

Many people will disagree, and that’s ok. When it comes to Arthur we will never reach a consensus.

However, considering the archaeological evidence at South Cadbury Castle, along with its location and the apparent activity during the Arthurian period, it seems quite possible that if there was an historical Arthur, he would undoubtedly have been familiar with this magnificent hill fort.

Me (Adam) standing at the location of the south western gate house

Was this just another strong point in the British defensive network? Or was it the Arthurian power centre that has come to be known as Camelot?

Whatever the answer is, it is surely fascinating, and perhaps unattainable. But then, that is what makes these historical mysteries so intriguing.

If you ever manage to roam the lands In Insula Avalonia, just be sure to make your way to South Cadbury Castle. Walk up the steep slopes, and through the gate, and know that you may just be walking in the footsteps of Arthur.

Thank you for reading and have a wonderful, safe Holiday Season.

See you in 2015!

Arial view of South Cadbury Castle from the South